Introduction

Since the late 2000s economic and immigration crises have challenged the European Union (EU), provoking, among other political reactions, the success and consolidation of so-called Eurosceptic parties all over Europe. While until 2004 such parties constituted only a scattered minority in the European Parliament (EP), since the last two rounds of EP elections, especially after 2014, extreme left-wing and right-wing parties rose in consensus at the expense of their mainstream counterpart. Euroscepticism is the concept used to label such forces even though it still lacks a clear-cut definition (Sørensen, Reference Sørensen2008; Leconte, Reference Leconte2015; Cotta, Reference Cotta2016; Usherwood, Reference Usherwood2016).

This work re-conceptualises Euroscepticism in terms of opposition to the EU (EU-opposition), disentangling four main targets to which opposition may be directed: EU-policies, EU-elite, EU-regime, and EU-community. Once defined, EU-opposition is applied to the empirical observation of the Italian Five Stars Movement (FSM) and the British United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) to understand their critique of the EU expressed in the EP where they work together in the same party group [the Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy (EFDD)] despite being different in many ways.

To do so, this work focusses on the analysis of speeches delivered by their Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) during the plenary sessions of the EP. The work’s central objective is to explore differences and similarities between the FSM and UKIP’s positioning to the EU, providing an in-depth description of their opposition.

The empirical evaluation of EU-opposition applies a methodology of content analysis on the collected speeches inspired by the Comparative Manifesto Project (CMP). The results obtained from the coding procedure are used to build an index of opposition/support for the four above-mentioned targets of EU-opposition. A first quantitative evaluation is coupled with a qualitative assessment of the character of their EU-opposition; is it pragmatic, thus oriented to the substance of the problems or principled, thus, rejectionist in nature?

The work starts by presenting UKIP and FSM, stressing their differences and focussing on their presence in the EP. It then reviews the literature concerning the definitions of Euroscepticism, stressing the pros and cons of this concept. Afterwards, it proposes to reconceptualize Euroscepticism in terms of ‘EU-opposition’, providing a definition thereof. The work then focusses on the EP as a directly elected supranational arena where parties can use speeches to express their positioning with regard to the EU. The paper then presents the data and the method applied in the empirical analysis. The following section reports the results while some conclusive remarks and avenues for further research are highlighted in the conclusion of the paper.

UKIP and FSM

UKIP and FSM were among the winners of the last EP election. UKIP got 26.77% of the national vote share, becoming the first party represented in the EP for the UK, winning 24 seats in the Strasbourg chamber. Although FSM’s result has been described as a political setback (Bordigon and Ceccarini, Reference Bordigon and Ceccarini2014), this party competed in its first EP election, scoring 21.2% of the vote share, obtaining 17 seats and becoming the second most voted party in Italy – a country described in the past as pro-EU (Quaglia, Reference Quaglia2008).

UKIP and FSM work together in the EFDD, an EP political group, essentially built around a political agreement between Beppe Grillo and Nigel Farage (Franzosi et al., Reference Franzosi, Marone and Salvati2015). However, these two parties differ in at least three main perspectives: (1) their ideological standpoint; (2) their ‘relevance’ at the national level; (3) the method used for the selection of their MEPs.

UKIP is classified as a right-wing populist party or right-wing anti-establishment party (Hayton, Reference Hayton2010; Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Whiteley, Borges, Sanders and Stewart2016). Conversely, the FSM does not identify itself with the traditional left/right cleavage; officially, it is neither right wing nor left wing.Footnote 1 This ideological divergence partially explains EFDD’s lower voting cohesion (around 51%) when compared with the other political groups in the EP (ECR nears 76%; ALDE scores ~90%; and the most cohesive group, the EPP, scores around 95%).Footnote 2 Thus, contrary to the main findings in the literature assessing that national parties in the EP aggregate according to their ideology or policy affinity (McElroy and Benoit, Reference McElroy and Benoit2010; Bressanelli, Reference Bressanelli2012), the ‘union’ between UKIP and the FSM is apparently guided by the ‘pursuit of office goals and pragmatic objectives’ (Bressanelli, Reference Bressanelli2012: 740), facilitated by material and non-material resources available to party groups in the EP (see fifth section).

Second, both UKIP and FSM are in opposition to their national governments; however, their relevance is different. Indeed, UKIP has no representative in the House of Commons,Footnote 3 while the FSM, after the 2013 Italian national election, occupies 109 seats in the Chamber of Deputies alongside 54 seats in the Senate.

Third, the UKIP’s MEPs come from previous political experience, while the FSM uses a random method for the selection of its representatives, based on (restricted) consultation among party’s members (Cammino and Verzichelli, Reference Cammino and Verzichelli2016).

However, these two parties are equated by their criticism to the EU, being commonly labelled as Eurosceptic: one ‘harder’ (UKIP) and one ‘softer’ (FSM). Table 1 reports the three most used quantitative ‘measures’ of party-based Euroscepticism: the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES) (Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, Edward, Hooghe, Jolly, Koedam, Kostelka, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Schumacher, Steenbergen, Vachudova and Zilovic2015), the Euromanifesto Study (EMS) (Schmitt et al., Reference Schmitt, Braun, Popa, Mikhaylov and Dwinger2016), and the CMP (Volkens et al., Reference Volkens, Lehmann, Matthieß, Merz and Regel2016).

Table 1 Three most used quantitative ‘measures’ of party-based Euroscepticism

FSM=Italian Five Stars Movement; UKIP=United Kingdom Independence Party; CHES=Chapel Hill Expert Survey; EU=European Union; EC=European Commission; EP=European Parliament; CMP=Comparative Manifesto Project; EMS=Euromanifesto Study.

According to CHES data, both parties consider the EU as a relevant issue; their leaderships are strongly opposed to European integration and do not endorse their countries’ membership in the EU. Neither the EMS nor the CMP report data on the FSM’s positioning to the EU integration, which could be interpreted as a lack of salience of this issue to the party.Footnote 4 However, according to EMS’ coders rating, both parties are against the European integration project with a difference of 2 points on a 0–10 scale, indicating some elements of divergence.

Therefore, while according to the literature these two parties’ positioning with regards to the EU is different, this difference is only partially confirmed by the quantitative ‘measures’ reported above. Furthermore, such measures are not able to portray quantitatively FSM and UKIP’s nuanced positions to the EU. What aspect of the EU do these two parties oppose? To answer this question, this work argues that it is time to discuss more explicitly the concept of Euroscepticism in the next section.

Euroscepticism: a contested concept

The word Euroscepticism originates in the British media; The Times firstly used it in 1985 to describe one side of the Conservatives’ intra-party division regarding the creation of a single market (Harmsen and Spiering, Reference Harmsen and Spiering2004). Key political events like the negotiations for the Single European Act or Margaret Thatcher’s famous Bruges speech contributed to the diffusion and crystallisation of Euroscepticism (Usherwood and Startin, Reference Usherwood and Startin2013). However, the Maastricht Treaty is widely regarded as the real turning point for the development of a whole body of literature concerning criticism of the EU (Ray, Reference Ray1999; Flood, Reference Flood2002; Taggart, Reference Taggart2006; Usherwood and Startin, Reference Usherwood and Startin2013; Brack and Startin, Reference Brack and Startin2015). From Maastricht onwards the community of member states (MSs) became a ‘union’ of European peoples with shared objectives and values (art. 1 of the Maastricht Treaty). Maastricht marks the passage from ‘permissive consensus’ to ‘constrained dissensus’. Until there was agreement among the political elite (consensus) alongside the absence of public conflict, or awareness, on its scope and objectives (permissive), the European integration project could progress smoothly. When political dissensus and public conflict began, ‘the elite became vulnerable. And … so too did their projects, and in particular that for Europe’ (Mair, Reference Mair2013: 114).

Furthermore, after Maastricht the demarcation between national and supranational competencies in several policy areas began to fade and the use of referenda to ratify changes to the EU treaties became widespread (see Mair, Reference Mair2007 for an overview), determining a departure from the normal political practices, a move toward a more plebiscitary politics (Taggart, Reference Taggart2006).Footnote 5

During the period of constrained dissensus only some scattered and small Eurosceptic formations existed.Footnote 6 This contributed to Euroscepticism being considered a niche and passing phenomenon, ‘a grit in the system that occurs when political systems are built and develop’ (Usherwood and Startin, Reference Usherwood and Startin2013: 2).

Some events crucial to the evolution of the EU contributed to the spread of Euroscepticism, like the big-bang enlargement to the East (in 2004), the failure of the negotiations for the Constitutional Treaty and the subsequent signing of the Lisbon Treaty in 2009, alongside more recent developments like both the economic and the immigration crisis or the ‘yes vote’ to the so-called Brexit referendum (June 2016) that will change EU’s geography.

A now full-fledged subfield of European studies (Mudde, Reference Mudde2012) aims at studying such criticism from two main perspectives: (1) theorising and defining Euroscepticism; (2) explaining its drivers. This literature review focusses on the first aspect, reporting the main definitions of Euroscepticism. Taggart is the first scholar to conceptualize Euroscepticism as the ‘idea of contingent or qualified opposition, as well as incorporating outright and unqualified opposition to the process of European integration’ (Taggart, Reference Taggart1998: 366). This definition was further split, with a dichotomy between ‘hard’ (parties rejecting the EU as such) vs. ‘soft’ Euroscepticism (parties dissatisfied either with the current state of the EU or with its policies) (Szczerbiak and Taggart, Reference Szczerbiak and Taggart2002). This model, despite being widespread (Usherwood, Reference Usherwood2016), received criticism from three main perspectives. First, soft Euroscepticism is so broadly defined that virtually every disagreement with the EU could be classified as Eurosceptic (Mudde and Kopecký, Reference Mudde and Kopecký2002). Second, there is no clear-cut distinction between the two poles of the continuum (Mudde and Kopecký, Reference Mudde and Kopecký2002; Beichelt, Reference Beichelt2004; Vasilopoulou, Reference Vasilopoulou2009); indeed, the soft pole is less delineated than its harder counterpart. In fact, Taggart and Szczerbiak warn about considering the parties that ‘only criticize one or two EU policy areas’ as soft Eurosceptic (Szczerbiak and Taggart, Reference Szczerbiak and Taggart2008: 14). This assertion led scholars to question how many and which policy areas one party should criticize to be considered as Eurosceptic (Vasilopoulou, Reference Vasilopoulou2009). Finally, this dichotomy does not stress the differences between opposition to the ideas underpinning the EU integration project and their ‘embodiment’ (Mudde and Kopecký, Reference Mudde and Kopecký2002: 300).

Building on Easton’s distinction between diffuse and specific support for a political regime (Easton, Reference Easton1965), Mudde and Kopecký (Reference Mudde and Kopecký2002) propose a typology presenting four ideal-types categories (Euroenthusiasts, Eurosceptics, Eurorejects, and EuropragmatistsFootnote 7 ). Despite encompassing both negative and positive stances to the EU (Rovny, Reference Rovny2004), this typology still presents some problems. First, the Europhile/Europhobe distinction is not accurate enough to recognize all the nuanced parties’ stances with regard to the EU (Flood, Reference Flood2002). Second, the Europragmatist category (Europhobics sustaining the EU) is counterintuitive as the same authors suggest. Third, the Eurosceptic category is not enough to encapsulate all the nuanced criticism of the EU (Krouwel and Abts, Reference Krouwel and Abts2007). Finally, it is not so clear what should constitute the ‘general ideas’ underlying the process of European integration and the general practices of the EU: ‘There is no trans-historical general practice of European integration since integration practice can – and indeed does – change quite fundamentally’ (Kný and Kratochvíl, Reference Kný and Kratochvíl2015: 209).

From these first theoretical efforts, different typologies flourished to address both popular and party-based Euroscepticism. However, according to some scholars, ‘these typologies tend to differentiate between different degrees of the phenomenon without formulating a satisfactory definition’ (Crespy and Verschueren, Reference Crespy and Verschueren2009: 381). This work reports the most cited/applied ones starting from Flood (Reference Flood2002), who proposes a set of six categories that should provide researchers with some guidelines about parties’ positioning to the EU: EU-rejectionist, EU-revisionist, EU-minimalist, EU-gradualist, EU-reformist, and EU-maximalist. Sørensen classifies popular Euroscepticism, identifying six broad types of attitudes toward the EU deriving from: (1) the concern about the integrity of the nation state; (2) the values of the EU; (3) the transfer of new competencies to the EU; (4) the economic rationale of integration; (5) the (lack of) emotional attachment to the EU; and (6) the stances toward the principles of the EU (Sørensen, Reference Sørensen2004: 3). Conti (Reference Conti2003) conceptualizes parties’ positions to the EU building on the famous ‘hard’ vs. ‘soft’ dichotomy, and adds three further categories to address both neutral and positive stances to the EU: ‘no commitment’ (no clear attitude to the EU); functional Europeanism, (support for the EU as a function of domestic interests or parties’ objectives) and ‘identity Europeanism’ (principled support for the EU). Rovny (Reference Rovny2004) conceptualises party-based Euroscepticism along two lines: the first dealing with its magnitude (the hard vs. soft distinction) and the second one dealing with the motivations guiding it (ideology and strategy). Vasilopoulou (Reference Vasilopoulou2009) categorizes Euroscepticism depending on parties’ position with regard to the principles, practices, and future development of the EU: rejecting Euroscepticism (principles of the EU), conditional Euroscepticism (practices of the EU), and compromising Euroscepticism (future of the EU).

Generally, from this brief literature review, what emerges is that the more complex and detailed the typology, the more difficult it is to operationalise it; relying on complex models for the observation of Euroscepticism requires a considerable amount of data with the risk of falling in the non-mutual exclusivity of the formulated categorization. Thus, applying one of the aforementioned frameworks to the empirical analysis of Euroscepticism implies a decision on ‘how “inclusive” or “exclusive” one seeks to be’ (Vasilopoulou, Reference Vasilopoulou2013: 156).

As an example, President Hollande described the French socialist party’s (PS) results in the last EP election as a ‘mistrust towards Europe’. Besides describing himself as a ‘European’ and stating the need for France to stay in Europe (‘Europe cannot continue without France and France’s future is in Europe’), he criticizes that the EU ‘has become unintelligible … All this cannot last. Europe has to be simple and clear in order to be effective where it is required to be, and pull back where it is not necessary’.Footnote 8

Following, for example, Kopecký and Mudde’s typology, the last cited part of Hollande’s speech should be considered as Eurosceptic (a general Europhile perspective combined with a pessimistic view of Europe’s practices). However, this definition clashes with the PS’s orientation to the EU.Footnote 9 In other words, a pro-EU party criticizing the EU is barely classifiable into one of the aforementioned typologies.

Beside these considerations, three further biases affect the concept of Euroscepticism. First, the structure of the term itself (the ‘euro’ prefix, the ‘sceptic’ component, and the ‘ism’ suffix) leads to an interpretation of Euroscepticism as a deviation from a pro-European ‘religious orthodoxy’ (Cotta, Reference Cotta2016), while the ‘ism’ suffix equates the concept to a sort of ideology even though Euroscepticism should not be considered as an ideology per se (Usherwood, Reference Usherwood2016) but as an element connoting other ideologies.

Second, the term is negatively and normatively constructed and widely used to disparage political competitors (Leconte, Reference Leconte2010; Pasquinucci and Verzichelli, Reference Pasquinucci and Verzichelli2016). Moreover, it implicitly recognizes a positive pro-EU pole, which in turn is not defined: ‘[T]he undefined nature of “pro-Europeanism” and the lack of academic consensus on the very nature of the EU itself make it difficult to reach an agreement on what Euroscepticism actually is’ (Leconte, Reference Leconte2015: 254). Furthermore, the academic literature has normatively described Euroscepticism as a phenomenon to be ‘confronted with’ or to be ‘responded to’ (Leconte, Reference Leconte2010: 264). ‘EU studies have long been influenced by the proximity between many EU experts and EU Institutions, or, at least, by the shared belief in the durability of the integration process’ (Leconte, Reference Leconte2015: 252).

Finally, the available definitions of Euroscepticism do not clearly differentiate the targets of criticisms: EU policies, the elite responsible for the integration project, the EU-regime or the EU as a whole. Indeed, beside the intensity of the expressed ‘sentiment’, the targets may also vary, thus they need better characterisation (Krouwel and Abts, Reference Krouwel and Abts2007).

Starting from all these considerations, as suggested by Cotta (Reference Cotta2016), an alternative approach is to abandon (or re-conceptualize) Euroscepticism in favour of a more neutral one: opposition. The next section provides a definition of EU-opposition.

Defining EU-opposition

Although this paper does not aim to provide a complete review of the literature concerning opposition (for this purpose, see Brack and Weinblum, Reference Brack and Weinblum2011), theorisations of this concept are affected by two main problems. First, the traditional literature working with opposition has assimilated it to the notion of checks and balances, institutionalized conflict or minority parties. Second, the literature creates a normative distinction between the classical and legitimate opposition and the anti-systemic one. This Manichean view contributed to the emergence of two separate fields of research (Brack and Weinblum, Reference Brack and Weinblum2011): one dealing with opposition parties competing for governmental positions [the ‘classical’ (Kirchheimer, Reference Kirchheimer1964; Dahl, Reference Dahl1966), ‘real’ (Sartori, Reference Sartori1966), or ‘normal’ (Schapiro, Reference Schapiro1967) opposition] and one concerning opposition as a protest toward the very political system [the ‘anti-system’ (Kirchheimer, Reference Kirchheimer1964; Sartori, Reference Sartori1966) or ‘principled’ (Dahl, Reference Dahl1966) opposition].

To solve these problems, Brack and Weinblum (Reference Brack and Weinblum2011) define opposition as, ‘A disagreement with the government or its policies, the political elite or the political regime as a whole, expressed in the public sphere, by an organized actor through different modes of action’. This ‘neutral’ definition has two main advantages: (a) it is flexible and potentially applicable to all political systems; (b) it details the targets of opposition as:

1. the government;

2. the policies enacted by the government;

3. the political establishment (opposition and governing elite);

4. the political regime (e.g. proposing reforms of its institutions).

With some clarifications, this definition is also applicable to the study of EU-opposition (Cotta, Reference Cotta2016). Indeed, it is plausible to think that an actor (a political party) opposes the policies that the EU enacts; the EU establishment, ‘public officials and institutional actors that exercise EU governance’ (Serricchio et al., Reference Serricchio, Tsakatika and Quaglia2013); the EU-regime particularly focussing on EU-institutions (e.g. the EP, the European Commission, the Council of Ministers and so on), on their performance (Krouwel and Abts, Reference Krouwel and Abts2007) and on their values (e.g. democracy, rule of law, representativeness).

Such forms of opposition are reasonably detectable at the supranational level; however, scholars are still reluctant to talk about opposition in the EU context mainly because it is difficult to clearly identify the main addressee of political opposition: the government (Cotta, Reference Cotta2016).Footnote 10 Even if it is true that leaders of several EU institutions are growing in prominence and could be seen as a ruling elite of the EU, this does not provide a clear-cut indication of what the government of the EU is. The task is made more difficult by the EU’s complex institutional architecture. Is the government of the EU the Commission, the Council, the European Council or all of themFootnote 11 ?

Dealing with EU-opposition, a further target should be added to the analysis: ‘The existing political community with the central objective of changing its borders more or less radically, e.g., through a secession’ (Cotta, Reference Cotta2016: 238). Forms of opposition addressing this target seek to reform the EU (e.g. preaching for a solidarity-based union); deny the EU’s competencies in various policy areas; reject the EU as a whole or one or more of the geometries deriving from the process of European integration. The implementation of specific policies (e.g. the common monetary policy) also defines a territorial scope of that policy (e.g. the Euro area). Whenever a party opposes either its country’s belonging to the group of MSs constituting the ‘territorial scope’ of a specific policy or the very existence of that ‘territorial scope’, it may demand either the exit from that area of application or the ‘elimination’ of that area (e.g. asking for the exit from the Euro area or the Schengen area).Footnote 12 Consequently, this paper defines EU-opposition as:

A disagreement with the policies enacted by the EU, its political elite, the EU regime, the political community as a whole or all its potential geometries, expressed in the public sphere, by an organized actor through different modes of action.

This definition implicitly defines EU support as contrary to EU-opposition (thus enabling its application not only on Eurosceptic parties but also on their mainstream counterpart). Differently from Euroscepticism, the concept of EU-opposition precisely identifies the targets of criticism, thus not considering the European integration project as a monolithic unit. Furthermore, critiques of the EU are not normatively/negatively judged.

Having detailed the targets of opposition, the analysis should also investigate its character; is it a pragmatic opposition, oriented to the substance of the problems or is it an opposition based on principle (principled opposition), thus more rigid?

Using MEPs speeches to observe EU-opposition in the EP

The EP is not the only arena where EU-opposition may be found; however, it is the only directly elected institution with a supranational spirit (Murray, Reference Murray2004). It is one of the EU decision-making institutions that contributes to the creation of binding laws (Lord, Reference Lord2013). Indeed, it represents a unique institutional arena where national parties from all EU MSs work together, on the same topic at the same time, having access to a public profile that is of high importance when there is media attention (Usherwood, Reference Usherwood2016).

Besides this, the EP provides national parties that gather in party groups with the necessary resources to stimulate their political activity (Usherwood, Reference Usherwood2016).Footnote 13 In many cases (e.g. UKIP), such resources are almost the only one available to national parties that may use them to achieve their objectives.

Literature concerning the activity of MEPs in the EP generally relies on roll call votes (RCVs) as the data source (e.g. Hix et al., Reference Hix, Noury and Roland2007), mainly concluding that representation in the EP is structured along the traditional left–right split, and that MEPs belonging to party groups are generally cohesive in their voting behaviour (Hix et al., Reference Hix, Noury and Roland2007; Lord, Reference Lord2013). However, such data are not free from problems; RCVs represent only one-third of the total amount of votes held in the EP (Carrubba et al., Reference Carrubba, Gabel, Murrah, Clough, Montgomery and Schambach2006), and may be asked either by a party group in the EP or by national parties to check the loyalty of their members.

Besides voting, MEPs use speeches to express their views on several arguments. Even if it is true that much of the real discussion concerning specific EU policies happens in committees, participating in debates is an opportunity to provide a ‘public justification of the entirety of the Union’s legislative process’ (Lord, Reference Lord2013: 253). Speeches generally do not result in tangible conclusions but they may be used by MEPs to present their national parties’ stances concerning specific objectives, since the stakes for parties are much lower with speeches than with votes (Rasmussen, Reference Rasmussen2008); MEPs disagreeing with the EP party group’s line may use speeches to present their national party’s positions (Slapin and Proksch, Reference Slapin and Proksch2015).

EP’s plenary speeches are structured following strict rules concerning the allocation of speaking time; they generally open with a statement by the Commission followed by rapporteurs (and shadow rapporteurs) working in specific committees and by a proper debate held among MEPs. The allocation of speaking time is granted to both party groups and non-attached members by the European Union-Europarl (2014) (rule no. 162). A verbatim report of the proceeding of each sitting is ‘drawn up as a multilingual document in which all oral contributions appear in their original language’ (EP rule of procedure no. 194). The availability of such data represents a rich resource that has already attracted the attention of several scholars.Footnote 14 For the purposes of this analysis speeches represent a nuanced resource that MEPs can use to publicly oppose or support one or more of the four above-mentioned targets of EU-opposition. Starting from these considerations, the next section illustrates the methodology used in the analysis.

Data and method

This work focusses on UKIP and FSM MEPs’ speeches delivered during the first 2 years (May 2014–December 2016) of the VIII EP legislature, related to three policy areas:

1. immigration, asylum, and border control;

2. economyFootnote 15 ;

3. environmental protection.Footnote 16

The first two issues are directly related to the two main crises that Europe is experiencing, thus constituting two ‘transnational, politically significant, nationally divisive and ideologically divisive’ areas (Braghiroli, Reference Braghiroli2015: 110). The third issue – environmental protection – is chosen for three main reasons: first, environmental issues (e.g. climate change) are pressing nowadays; second, the EU plays a prominent role in this field; and, third, besides not being directly crisis-related, the economic crisis has had an impact on it (Burns and Tobin, Reference Burns and Tobin2016).

Since the Maastricht Treaty the EU increased its powers in these three fields; moreover, since Lisbon, decisions concerning these policy areas are taken under the ordinary legislative procedure where both the EP and the Council of Ministers have a deciding vote in the legislative process.Footnote 17 Focussing on these three issues allows the observation of all potential aspects of EU-opposition comparing parties’ attitudes towards the EU in crisis and non-crisis-related issues.

Table 2 reports the total number of used speeches by policy area, the average number of quasi-sentences for each speech and the average speech length expressed in average number of tokens (each word contained in a text) per speech.Footnote 18 A total number of 1632 speeches (671 for the FSM and 961 for UKIP) has been collected and analysed.Footnote 19

Table 2 Number of collected speeches by issue for the period between May 2014 and December 2016

FSM=Italian Five Stars Movement; UKIP=United Kingdom Independence Party.

The coding method applied in this work is inspired by the CMP and is essentially divided into two phases: (1) speeches are divided into quasi-sentences; (2) each quasi-sentence is codified in one of the 12 defined categories, three for each of the four main targets of EU-oppositionFootnote 20 (EU-policies, EU-elite, EU-regime, and EU-community). The categories assigned to each target are: ‘directional positive’, ‘directional negative’, and ‘non-directional’ (e.g. EU-policies directional negative, EU-policies directional positive, and EU-policies non-directional). The first two categories indicate if an MEP addresses a specific target negatively or positively, while the third one classifies quasi-sentences not providing any judgement (e.g. summary of the procedure under discussion).

Similarly to CMP methodology (see footnote 4) this work assumes that national parties in the EP emphasize a specific target positively or negatively, the more that target is important to them. Consequently, the relative mention of different targets provides a direct measure of their importance to the party (Lowe et al., Reference Lowe, Benoit, Mikhaylov and Laver2011).

The frequencies of coded quasi-sentences are used to calculate an index of opposition/support for each of the proposed targets:

where CN represents the coded directional negative quasi-sentences; CP the coded directional positive quasi-sentences; and N the total number of coded quasi-sentences. The index is an adaptation of Prosser’s (Reference Prosser2015) re-elaboration of Lowe et al.’s ‘logit scale of position’ (Lowe et al., Reference Lowe, Benoit, Mikhaylov and Laver2011) that is, in turn, an improvement of CMP’s left-right scale. Adding 1 to each element ‘makes the value of no quasi-sentences in a component consistently 0’ (Prosser, Reference Prosser2015: 96) since

![]() ${\rm log}_{{{\rm (1)}}} \,{\equals}\,0$

. Furthermore, the log element enables researchers to avoid centrist or extremist biases.

${\rm log}_{{{\rm (1)}}} \,{\equals}\,0$

. Furthermore, the log element enables researchers to avoid centrist or extremist biases.

The obtained index ranges from −1 to 1, where −1 indicates the total support for one of the specific targets under analysis, 1 indicates the total opposition to one of the aforementioned targets and 0 indicates either the absence of opposition/support or an equal balance between coded-negative and coded-positive quasi-sentences.

The production of an ‘opposition/support’ index is coupled with a comparative observation of the ‘character’ of opposition (principled vs. pragmatic). To do that, different values are allocated to the coded segments for each proposed target such that: the value of 1 corresponds to pragmatic opposition and the value of 2 refers to principled opposition.Footnote 21 If the majority of the coded quasi-sentences are pragmatically connoted then the opposition will be regarded as pragmatic and vice versa.

Results

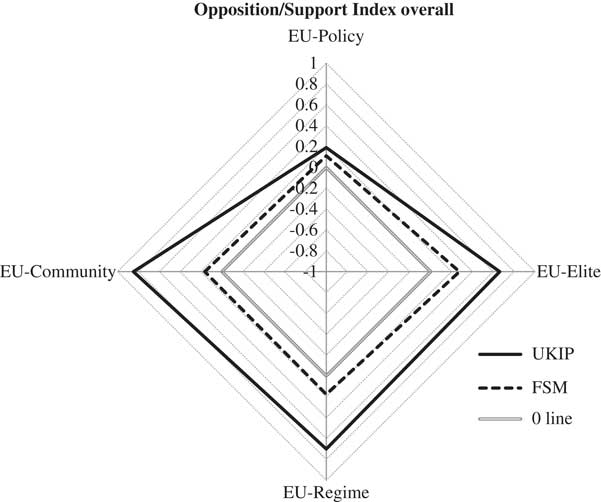

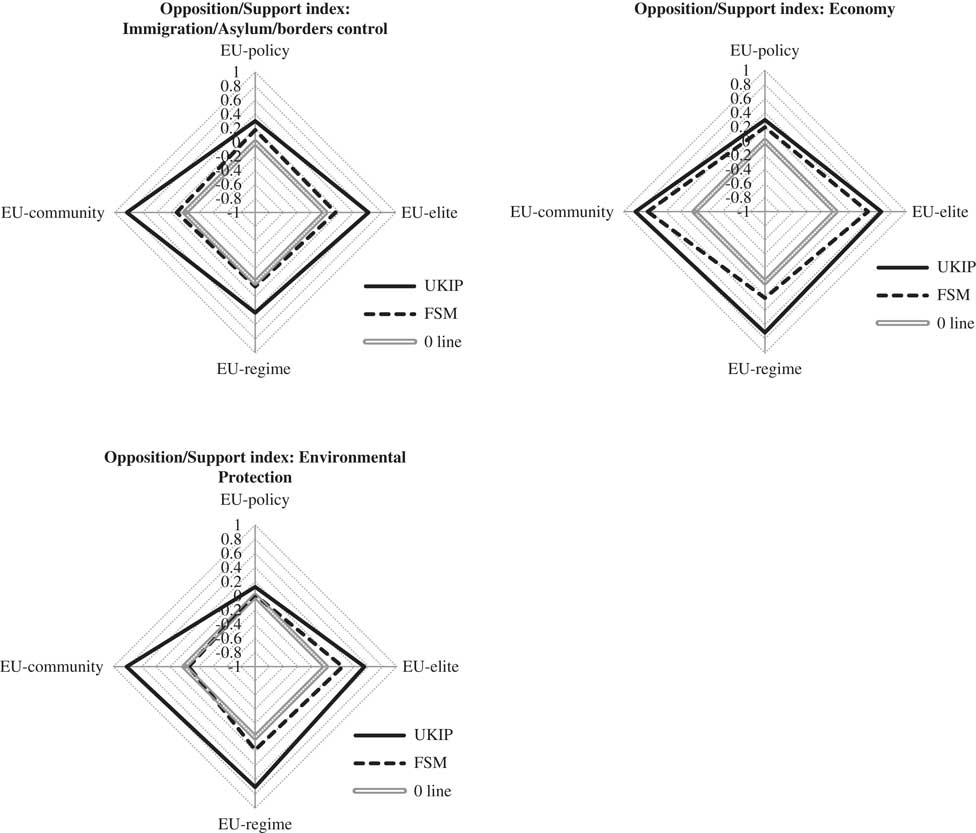

Figure 1 below reports the opposition/support index for the three issues under consideration. In the spider plots, the continuous line represents UKIP, the dotted one shows FSM, while on the grey line (0 line), the index takes the value of 0. The higher the value of opposition, the further away (in the positive side) the lines are from the ‘0 line’; conversely, if the party supports one of the four targets, the line is on the negative side of the graph.

Figure 1 Spider plot representing the overall Opposition/Support index.

Considering the aggregate picture, the most addressed target by UKIP is the EU-community (scoring around 0.85 points) followed by the EU-regime, the EU-elite and, finally, the EU-policies. Conversely, the EU-elite attracts the majority of the FSM’s criticism (around 0.28 points). The other three proposed targets take values ranging between 0.11 and 0.18 thus denoting a low overall level of opposition, to the EU-regime, the EU-community, and the EU-policy in declining order.

From the aggregate picture, the two parties’ EU-opposition differs radically; FSM in fact shows a lower level of opposition to all the four proposed targets, and the EU-elite is the only target attracting a comparatively higher opposition.

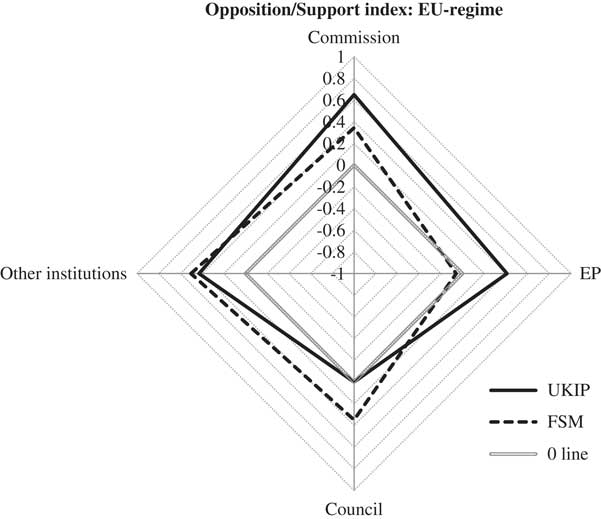

At the aggregate level, it is also interesting to observe how criticism to the EU-regime is distributed (Figure 2 below). UKIP directs the majority of its critique to the European Commission (EC; around 0.64 points), while it represents the third most addressed target by the FSM (around 0.34 points). FSM concentrates its criticism on the ‘other institutions’ (e.g. the ECB) targeted similarly also by UKIP (around 0.43 points). The Council is the second most important target for the FSM (around 0.35 points) while it is not addressed by UKIP. The most remarkable difference between the two parties concerns the EP; differently from UKIP (around 0.40 points), the FSM shows a small degree of support (around −0.06 points) for the EP. FSM’s MEPs are in fact aware of the scarce powers of the EP: ‘[T]he European Parliament is completely powerless against Member States’ egoism’ (Ignazio Corrao).Footnote 22 However, they consider it as a fundamental institution representative of the European Citizens: ‘I’d like to recall that the European Parliament is the only institution democratically elected by citizens, it represents, de facto, European citizens’ will’ (Laura Ferrara).

Figure 2 Spider plot representing the Opposition/Support index for EU-regime. UKIP=United Kingdom Independence Party; FSM=Italian Five Stars Movement.

Figure 3 below reports the opposition/support index concerning each of the three policy issues analyzed. Starting from immigration/asylum and borders control, the inter-party comparison shows that FSM and UKIP behave differently. The first target addressed by UKIP is the EU-community (around 0.83 points), while FSM primarily focusses on EU-policies (0.17 points) and generally shows lower levels of opposition in all the observed targets.

Figure 3 Spider plots representing the Opposition/Support index for the three policy areas under analysis. UKIP=United Kingdom Independence Party; FSM=Italian Five Stars Movement.

UKIP’s MEPs blame the EU for taking over competencies that should be a matter of MSs, calling for an ‘intergovernmental approach’ to solve the immigration crisis: ‘Each country should manage its own policy and work together on a bilateral basis to deal with the current crisis’ (Diane James). Furthermore, they are critical of the Schengen area geometry considered as a ‘facilitator and accelerator of both the migrant crisis and the movement of terrorists within Europe’ (Jane Collins). UKIP’s critique to the EU-community in this field is even stronger, denying the existence of EU’s borders: ‘The EU is not a country, so I am really confused by the whole concept of why something that is not a country should look to control borders that do not exist’ (Bill Etheridge).

Contrary to UKIP, FSM’s MEPs address the EU-community as third most important target (0.11 points), being critical of the intergovernmental approach used to face the migration crisis: ‘We should understand if the intergovernmental approach that we are currently applying is really enough to face such an important issue, a disaster, an emergency with uncontrollable proportions’ (Ignazio Corrao). They do not accuse the EU of taking over MSs’ competencies, but conversely, desiring ‘another Europe’: ‘Well, we, as the FSM, are committed to propose a feasible alternative, to build another Europe, nevertheless, facts oblige us to think that this certainty might become a utopia, a broken dream, an illusion’ (Laura Ferrara).

FSM’s most addressed targets are the EU-policies (0.17 points), their primary request is to implement a binding quota system, to redistribute migrants: ‘Based on the principle of shared solidarity and fair allocation of responsibilities among all Member States, there is a need to create a quota system in order to redistribute who comes to Europe’ (Laura Ferrara). For UKIP, EU-policies represent the third target of opposition and differ diametrically in terms of content from FSM’s critique. UKIP in fact rejects the idea of a binding quota system: ‘EU refugee quotas are the wrong way to go about handling this situation’ (Jonathan Arnott).

UKIP’s second most addressed target is the EU-elite, criticized firstly for EU leaders’ adamant position toward potential Treaty changes: ‘[I]t is pretty clear that, actually, when it comes to renegotiation, nothing substantial can be achieved, because already all big bosses in Europe have said that the freedom-of-movement rules are not up for re-negotiation and that there will be no Treaty change on this point’ (Nigel Farage). Second, they are against the EU leaders’ ‘welcome culture’: ‘They have rejected the idea that Angela Merkel’s open welcome has caused millions of people to feel that they should come to the EU and they have rejected the idea that Australia’s solutions have meant fewer people dying’ (Steven Woolfe). Both parties are critical of the EU-Turkey agreement in managing the migration crisis, accusing the EU’s leader of hypocrisy, while for both parties the EU-regime represents the last target of opposition.

On economic issues, UKIP and FSM share their main target of criticism: the EU-community. UKIP blames EU’s power-grab vis a vis MSs: ‘As a UKIP MEP, this resolution goes against the fundamental principles of what I believe about economic policy, which could and should be the preserve of the Member States’ (Jonathan Arnott). Moreover, UKIP’s MEPs are particularly critical of the Euro area geometry: ‘[T]he only medicine with a hope of curing Europe is a euro exit and a return to the original currencies’ (David Coburn).

This aspect is shared by the FSM: ‘We stressed the need to change direction through a rapid introduction of democratic mechanisms that allow the exit from the Euro while preparing a plan for a coordinated and controlled dissolution of the Euro area’ (Marco Valli). However, FSM’s MEPs do not directly criticize EU’s competencies in economic matters, but express a desire for an alternative Europe: ‘Who is honest enough knows that there are two alternatives: either there is a sure, sincere and frank will to build a social Union, a fiscal Union, without paradises, with a shared debt and, above all, founded on solid and really transparent institutions, or this fake monetary (but not economic) union must come to an end, the Euro was meant to be a wealth instrument that, in the end, became its negation’ (Fabio Massimo Castaldo).

FSM’s second most addressed target is the EU-elite. FSM’s MEPs are extremely critical of the president of the EC (Jean Claude Juncker) for his former role as Belgium Prime Minister in the context of the ‘LuxLeaks’ affair: ‘Mister President, until when will you damage us, the citizens, to guarantee billionaire profits to a few money-thirsty multinational enterprises’ (Giulia Moi).Footnote 23 Similarly, according to UKIP, Juncker was ‘involved in allowing corporations to extract exceedingly large profits from the ordinary citizens of Europe’ (Steven Woolfe).

UKIP strongly criticizes the EU-regime (second most addressed target scoring 0.71 points) blaming EU-institutions for their lack of democratic accountability: ‘[T]he fact that the Commission can tell the Council to withdraw funding from Member States without consulting the elected Parliament highlights the democratic deficit’ (Margot Parker). Both parties show a similar level of criticism toward the EU-policies in this field (relatively low when compared with the other three targets).

Also, in the field of environmental protection the two parties differ radically. UKIP addresses the majority of its critique toward the Community (around 0.81 points). It blames the EU to take over competencies that, according to them, should exclusively belong to MSs: ‘We believe that the best people to decide on natural habitats in Britain are the British people’ (Julia Reid).

Conversely, the FSM shows a low degree of support for the EU-community (around −0.06 points). FSM considers the EU’s role fundamental in environmental protection: ‘Yet, belonging to the CITESFootnote 24 will enable the Union to act with a single voice in facing international actors that have a less advanced legislation in the field, thus reinforcing its vision aiming at protecting plants and animals’ (Marco Zullo).

While FSM does not address much criticism to both the discussed policies and the EU-regime, for UKIP, EU-regime constitutes the second most addressed target (0.70 points) followed by the EU-elite (0.54 points). FSM concentrates the majority of its criticism on the EU-elite blaming the collusion between politicians and lobbies at the expenses of environmental protection: ‘Cars’ lobbies were able to win this battle and they convinced the Parliament that rejecting this legislative procedure would have meant the end of the big car producers and losses of jobs’ (Dario Tamburrano).

Besides the quantity of expressed opposition/support, this paper further investigates its character (principled vs. pragmatic). Table 3 reports the frequencies of FSM and UKIP’s coded-negative quasi-sentences for each policy area under examination.

Table 3 frequency distribution of coded-negative quasi-sentences (relative percentages for each target in parenthesis)

FSM=Italian Five Stars Movement; UKIP=United Kingdom Independence Party.

No remarkable difference between the two parties is detectable in the first two targets of EU-opposition (EU-policies and EU-elite) both addressed pragmatically. The only noticeable exception is UKIP’s principled opposition to the EU-elite in immigration/asylum/borders control (13% principled coded-negative quasi-sentences more then the pragmatic ones).

The character of the two parties’ opposition is remarkably different with reference to both the EU-regime and the EU-community (alongside the Euro area and the Schengen area). For what concerns the EU-regime, UKIP’s opposition is principled in all the three policy areas under consideration, thus denoting a general overall rejection of EU-institutions, their values, their competence and their performance. On the contrary, FSM shows a pragmatic opposition to the EU-regime in all four policy areas.

With reference to the EU-community target, while UKIP opposes it and all its analysed geometries in a principled way, FSM’s opposition is generally pragmatically oriented. What equates both parties is the principled character of their opposition to the Euro area, thus confirming the quantitative findings reported above. FSM’s coded-negative quasi-sentences related to the Euro area constitute around 62% of the total number of coded-negative quasi-sentences related to the EU-community – a percentage higher than UKIP’s (around 35% less than FSM) – and UKIP dedicates 67.5% of the coded-negative quasi-sentences to the principled critique of the EU in general.

Conclusions

Starting from a critical review of Euroscepticism, this work proposes to reconceptualize it in terms of opposition, providing a definition of EU-opposition that is non-normatively biased and flexible enough to be applied to the EU. It then empirically observes EU-opposition as expressed by UKIP and FSM in the EP. The data derived from the content analysis of FSM and UKIP’s speeches are used to formulate an index of opposition/support for four targets: EU-policies, EU-elite, EU-regime, and EU-community.

From the results reported above, three conclusions can be formulated. First, UKIP’s EU-opposition is always higher than FSM’s one. Second, the saliency of each proposed target differs between the two parties. UKIP concentrates its critique on the EU-community in all the examined policy fields. However, FSM’s most salient targets vary depending on the issue under discussion: EU-community in economic policy, EU-policies in immigration/asylum/border control and EU-elite in environmental protection. The two parties behave more similarly on economic policy. Indeed, both UKIP and FSM preach for the dissolution of the Euro area. However, also in this policy field, UKIP rejects the EU in general while the FSM leaves some room to manoeuvre for the development of an alternative Europe, thus not rejecting EU competencies in the field (as UKIP does). Third, UKIP and FSM’s opposition also differs in its character; while UKIP rejects the EU on principle, the FSM is oriented towards a pragmatic critique with the only exception being its principled rejection of the Euro area.

The results of this analysis suggest that the two parties are an ‘odd couple’ inside of the same party group, differing both in the quantity and in the quality of their EU-opposition, findings that are in line with the low voting cohesion of EFDD. UKIP and FSM’s ‘union’ inside of the EFDD is mainly utilitarian. The two parties stay together in the EP to receive financial and institutional facilities despite the fact that there are remarkable differences in their positioning to the various aspects of the EU. This last assertion also explains the recent return of the FSM to the EFDD after their failed passage to the ALDE group and the consequent new deal between Nigel Farage and Beppe Grillo, causing the loss of David Borrelli’s co-chair position and the move of two MEPs to other two party groups: Marco Zanni to the ENF and Marco Affronte to the Greens.

From a more general perspective, this work opens up several avenues for future research. Further investigation could be oriented to understand how UKIP and FSM’s EU-opposition evolves over time, explaining the causes of the detected differences: Are they mainly guided by strategy? Are the parties’ ideologies influencing their position with regard to the EU? Are the differentiated effects of EU crises on Italy and the UK (e.g. economic crisis and immigration crisis) related to such differences? Furthermore, how will the future exit of UKIP from the EP (due to the Brexit) influence FSM’s stances towards the EU? After UKIP’s exit, the EFDD will not satisfy the numerical criteria reported by the European Union-Europarl (2014) anymore; will the FSM search for new partners or will it modify its positions to the EU adapting it to some other EP party groups?

Within the context of the pan-European arena of the EP, the EU-opposition concept can be applied to all national parties, thus to all MEPs, allowing a comparison of parties stances toward the EU both within and between party groups. A second step of the analysis could then move to understand the causes behind the detected differences/similarities.

The concept of EU-opposition can thus be used to study an enlarged sample of ‘Eurosceptic’ parties as well as their mainstream pro-European counterpart: Do mainstream pro-European parties oppose the EU? If yes, which aspects are mainly contested? Also in this case, the investigation could then move to understand what drives such patterns of differences/similarities.

EU-opposition can also be applied in a transnational context, allowing the study of national parties’ stances to the EU in various MSs, thus enabling a cross-country comparison.

Going beyond the realm of political parties, the concept of EU-opposition can be applied to study views on the EU as expressed by various types of organized actors (e.g. social movements) as far as data availability allows this tasks. This type of study could be conducted at the national level but also at the supranational (and transnational) level.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank two anonymous reviewers whose helpful comments contributed to increase the quality of the manuscript. Previous versions of this article were presented at the IPSA 24th World Congress of Political Science (held in Poznań between the 23rd and the 28th of July 2016) and at the American Political Science Annual meeting (held in Philadelphia between the 31st of August and the 1st of September 2016). The author thank Professor Amie Kreppel, Professor Sergio Fabbrini, Professor Maurizio Cotta, Professor Manuela Caiani, Professor Reinhard Heinisch, and Professor Duncan McDonnell for their valuable comments and suggestions to improve the quality of the paper. A special thank goes to my colleague Aleksei Gridnev, who kindly helped me with the collection of MEPs speeches using Python.

Financial Support

The research received no grants from public, commercial, or non-profit funding agency.

Data

The replication data set is available at http://thedata.harvard.edu/dvn/dv/ipsr-risp

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ipo.2017.24