No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

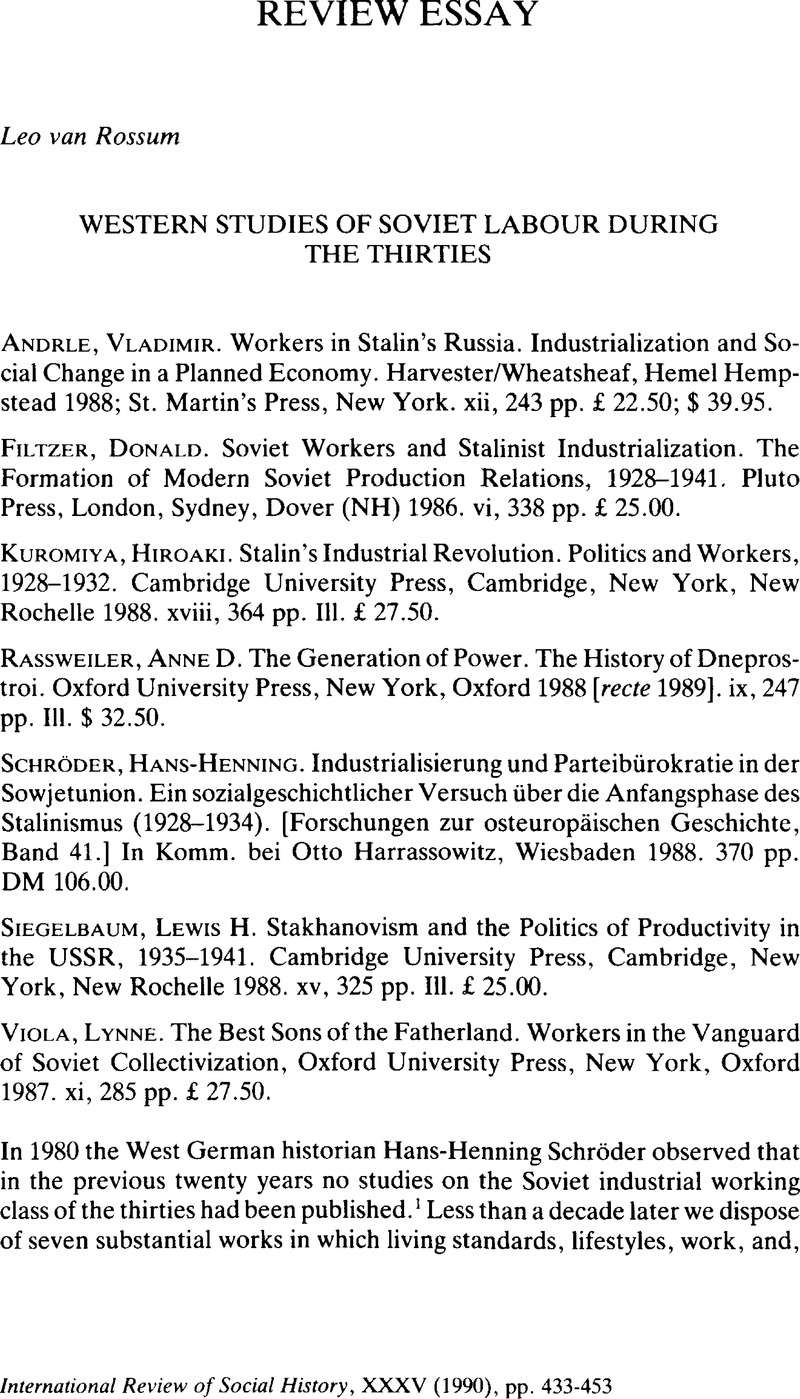

Western Studies of Soviet Labour During the Thirties

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 18 December 2008

Abstract

- Type

- Review Essays

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis 1990

References

1 Schröder, H. H., “Zum aktuellen Stand der Stalinismusforschung im Westen. Ein Literaturbericht”, Das Argument, 123 (1980), p. 719.Google Scholar

2 All these all concerned with “free” labour. A classic work on non-free labour was written by Dallin, David J. and Nicolaevsky, Boris N., Forced Labor in Soviel Russia (New Haven, 1947).Google Scholar

3 Carr, E. H. and Davies, R. W., Foundations of a Planned Economy, 1926–1929, vol. 1 (I–II) (London, 1969)Google Scholar; Bettelheim, C., Les Luttes de Classes en URSS, vol. 3 (I–II): 1930–1941 (Paris, 1982–1983)Google Scholar; Bailes, K. E., Technology and Society under Lenin and Stalin (Princeton, 1978)Google Scholar; Lampert, N., The Technical Intelligentsia and the Soviet State (London, 1979)CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Zaleski, E., Planning for Economic Growth in the Soviet Union 1918–1932 (Chapel Hill, 1971)Google Scholar, and Chapman, J., Real Wages in Soviet Russia since 1928 (Cambridge, MA, 1963).CrossRefGoogle Scholar Of course this list could be expanded; see the bibliographies of the books reviewed here.

4 Meyer, Gert, “Industrialisierung, Arbeiterklasse, Stalinherrschaft in der UdSSR”, Das Argument, 106–108 (1977–1978)Google Scholar; Barber, John, The Composition of the Soviet Working Class, 1928–1940, CREES Discussion Papers (Birmingham, 1978)Google Scholar; Hackenberg, Maria, Die Entwicklung der Disziplinar- und Strafmaßnahmen im sowjetischen Arbeitsrecht im Zusammenhang mit der forcierten Industrialisierung 1925–1935 (Berlin, 1978)Google Scholar; Rittersporn, Gábor T., “Héros du travail et commandants de la production. La campagne stakhanoviste et les stratégies fractionelles en URSS, 1935–1936”, Recherches, 32–33 (1978), pp. 249–275Google Scholar; Fitzpatrick, Sheila, Education and Social Mobility in the Soviet Union, 1921–1934 (Cambridge, MA, 1979)CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Tatur, Melanie, Wissenschaftliche Arbeitsor ganisation in der Sowjetunion 1921–1935 (Wiesbaden, 1979)Google Scholar; Barber, John, Notes on the Soviet Working-Class Family, 1928–1941, CREES Discussion Papers (Birmingham, 1980)Google Scholar; Barber, John, The Standard of Living of Soviet Industrial Workers, 1928–1941, CREES Discussion Papers (Birmingham, 1980)Google Scholar; Plogstedt, Sybille, Arbeitskämpfe in der sowjetischen Industrie (1917–1933) (Frankfurt am Main, 1980)Google Scholar; Barber, John, Housing Conditions of Soviet Industrial Workers, 1928–1941, CREES Discussion Papers (Birmingham, 1981)Google Scholar; Barber, John, “The Standard of Living of Soviet Industrial Workers, 1929–1941”, in Bettelheim, C. (ed.), L'Industrialisation de l'URSS dans les années trentes (Paris, 1981), pp. 109–122Google Scholar, and Meyer, Gert, Sozialstruktur sowjetischer Industriearbeiter Ende der zwanziger Jahre: Ergebnisse der Gewerkschaftsumfrage under Metall-, Textil-und Bergarbeitern 1929 (Marburg, 1981).Google Scholar

5 Süss, Walter, Die Arbeiterklasse als Maschine. Eine Industrie-soziologische Beitrag zur Sozialgeschichte der aufkommenden Stalinismus (Berlin, 1985)Google Scholar, falls outside the scope of this review because half of it covers the period of the NEP; furthermore, it takes a mainly industrial sociological approach. Barber, John, “The Development of Soviet Unemployment and Labour Policy, 1930–1941”, in Lane, David (ed.), Labour and Employment in the USSR (New York, 1986), pp. 50–65Google Scholar; Davies, R. W., “The End of Mass Employment”Google Scholar, in Lane, , Labour and Employment, pp. 19–35Google Scholar; Davies, R. W. and Wheatcroft, S. G., “A Note on the Sources of Unemployment”Google Scholar, in Lane, , Labour and Unemployment, pp. 36–49Google Scholar; Siegelbaum, Lewis H., “Production Collectives and Communes and the ‘Imperatives’ of Soviet Industrialization”, Slavic Review, XLV (1986), pp. 65–84CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Filtzer, Donald, “Labour and the Contradiction of Soviet Planning under Stalin: the Working Class and the Regime during the first years of Forced Industrialization”, Critique, 20/21 (1987), pp. 71–103Google Scholar; Baum, Ann Todd, Komsomol Participation in the Soviet First Five-Year Plan (Basingstoke, 1987)CrossRefGoogle Scholar, and Rittersporn, Gàbor T., Simplifications staliniennes et complications soviétiques. Tensions sociales et conflits politiques en URSS 1933–1953 (Paris, 1988).Google Scholar See also, of course, the books reviewed here.

6 See Kaiser, Hans, “Vom ‘Totalitarismus’ – zum ‘Mobilisierungsmodell’”, Neue Politische Literatur, XVIII (1973), pp. 146–169Google Scholar; the debate in The Russian Review, LXV (1986), pp. 375–413Google Scholar, which follows on from Sheila Fitzpatrick's “New Perspectives on Stalinism”, ibid., pp. 357–373; Bonwetsch, Bernd, “Stalinismus ‘von unten’: Sozialge schichtliche Revision eines Geschichtbildes”, SOWI, XVII (1988), pp. 120–124Google Scholar; “L'URSS actuelle. Ses origines, son analyse. Comptes rendus”, Annales, XL (1985), pp. 829–899, and XLII (1987), pp. 1195–1207.Google Scholar

7 See Fitzpatrick, , Education and Social Mobility, passimGoogle Scholar, and her introduction to Fitzpatrick, Sheila (ed.), Cultural Revolution in Russia, 1928–1931 (Bloomington, 1978), pp. 6–7.Google Scholar Later she distanced herself from the idea of a revolution initiated from below. See Fitzpatrick, , “New Perspectives”, p. 371.Google Scholar Chase has some revealing comments to make on this subject; see Chase, William J., Workers, Society, and the Soviet State. Labor and Life in Moscow, 1918–1929 (Urbana, 1987), p. 300Google Scholar: “To ask which ‘revolution’ anticipated or precipitated the other is to skirt the most important issue. What makes the period distinctive is that the “revolution from above' and the ‘revolution from below’ interacted, reinforced, and pushed each other along unforeseen lines.”

8 See the article by Fitzpatrick referred to in note 6 in which she names only Americans (and Gabor T. Rittersporn) in her discussion of new social historians. Compare note 23 further on.

9 The “Soviet Industrialisation Project” under the auspices of the Centre for Russian and East European Studies (CREES) in Birmingham; the research project “Indus trialisierung und Stalinisierung” promoted by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft; and the project “Sozialgeschichte der UdSSR 1917–1941” at the University of Bremen.

10 For an analogous use of the term “class war” see Fitzpatrick, , Education and social MobilityGoogle Scholar, and Andrle, , p. 2.Google Scholar

11 Kuromiya, , p. xiv.Google Scholar The last six words of this quotation are not explained here. See, however, p. 318.

12 According to Filtzer it is precisely this partial workers' control of the production process which blocked every attempt at reform after 1945 (pp. 120–121, 266–271).

13 For references to these authors see Siegelbaum, , pp. 2–6.Google Scholar For Filtzer see his Soviet workers, ch. 7. For what is probably the first interpretation in terms of a labour aristocracy see L. Sedov, adopted by his father: Markin, N. [L. Sedov], “Stakhanovskoe dvizhenie”, Biulleten' Oppozitsii, 47 (01 1936), pp. 4–10Google Scholar (a French translation may be found in Cahiers Léon Trotsky, 13 (1983), pp. 104–115Google Scholar). Trotsky, Leon, The Revolution Betrayed (New York, 1937), pp. 123–128.Google ScholarPasquier, A., Le Stakhanovisme: L'Organisation du Travail en URSS (Caen, 1937)Google Scholar is the first Western analysis published as a book. Benvenuti's, F.Fuoco sui sabotatori! Stachanovismo e organizzazione industriale in URSS: 1934–1938 (Rome, 1988)Google Scholar was only available to me in the form of an English summary, Stakhanovism and Stalinism, CREES (Birmingham, 1989). The study by Andrle being reviewed here has a not very analytical chapter on the Stakhanov phenomenon. The review by R. W. Davies of Siegelbaum's book in Soviet Studies, XLI (1989), pp. 484–487Google Scholar, cites two other articles, one written by J. P. Depretto in 1982 and a paper by John Barber, published by CREES (Birmingham, 1986). Maier's, RobertDie Stachanov-Bewegung: 1935–1938; der Stachanovismus als tragendes und verschärfendes Moment der Stalinisierung der sowjetischen Gesellschaft (Stuttgart, 1990)Google Scholar, unfortunately appeared too late to be included in this review article.

14 For example the Centre for Russian and East European Studies of the University of Birmingham (CREES).

15 Besides Viola, Rassweiler, Filtzer, Siegelbaum (and Kuromiya?) have, according to the prefaces of their books, visited libraries in the Soviet Union.

16 This is especially important in the case of the press, particularly for papers which represented a certain group interest, such as Trud (Trade Unions), Za industrializatsiiu (Commissariat of Heavy Industry), Plan (Gosplan), Predpriiatie (“The Managers”), Stakhanovets, Dneprostrol. Data were also published in various kinds of statistical publications, stenographic reports, sociological and economic monographs, political pamphlets, etc.

17 See the often quoted Shkaratan, O.I., Problemy sotsial'noi struktury rabochego klassa SSSR (Moscow, 1970)Google Scholar, or Vdovin, A. I. and Drobyzhev, V. Z., Rost rabochego klassa SSSR 1917–1940 gg. (Moscow, 1976).Google Scholar

18 The figures describe the situation which prevailed halfway through the year; source: Sotsialisticheskoe stroitel'stvo SSSR (Moscow, 1934), pp. 306–307.Google Scholar There are slight deviations in the total figures presented here compared with those from other contemporary sources. Data on the influx of workers come from Itogi vypolneniia pervogo piatiletnogo plana (Moscow, 1933), pp. 169–175.Google Scholar

19 The most thorough analysis of the census to date is: Meyer, Sozialstruktur sowjetischer Industriearbeiter, 1981 (note 4).

20 Examples of an impractical way of presenting figures may be found in Kuromiya, , pp. 89–92 and 213–217.Google Scholar

21 This contradicts Schröder who dates the fall in living standards from 1930 (pp. 99–107). Schröder bases his argument on a study by U. Weissenberger, Die Entwicklung von Realeinkommen und materieller Lage der Arbeiter und Angestellten in der Periode der Vorkriegsfünfjahrpläne (1928/29–1941), which was completed in 1980 and is now expected to be published in the autumn of 1990 as part of the Bremen project (see note 9).

22 Kuromiya, , pp. 110–115Google Scholar; Schröder, , pp. 110–111.Google Scholar For the concept of total guidance from above see Schwarz, , Labor, pp. 188–193Google Scholar; for that of partial guidance from above see Carr, and Davies, , Foundations, pp. 513–515.Google ScholarBaum, Todd, Komsomol Participation, pp. 24–30Google Scholar holds views close to those of Carr and Davies.

23 Rassweiler bases her description of the changes in the labour supply on two informative polls which Dneprostroi held amongst the work-force in May 1930 and March 1931 and published in his in-house paper (pp. 140–141). According to these, peasant participation increased from 24.3% in 1930 to 65.1% in 1931. But those analyzing the census noted that the peasants in 1930 tended to underreport their involvement for fear of being associated with the kulaks. They estimated that the proportion of peasants in 1930 was about 50%. In itself the sudden change in the labour supply from the village as reported by Rassweiler is exceptional for that period.

24 Kirstein, Tatjana, Die Bedeutung von Durchführungsentscheidungen in dem zentralistisch verfaßten Entscheidungssystem der Sowjetunion. Eine Analyse des stalinistischen Entscheidungssystems am Beispiel des Aufbaus von Magnitogorsk (1928–1932) (Berlin, 1984).Google Scholar Rassweiler does list two or three other German titles in her bibliography.

25 A comparison with data relating to the composition of a group of 550 delegates attending the All-Union Congress of Shock Workers in Moscow, December 1929, as given by Kuromiya, , pp. 319–323Google Scholar, results in the following:

Kuromiya's opinion (p. 321) that there were no particular differences between the composition of the delegations and that of the rank-and-file shock workers needs further substantiating.

26 Mark von Hagen presents an opposing view in his review in Slavic Review, XLVIII (1989), pp. 637–640.Google Scholar

27 It seems correct to mention the reviews of Viola's book which have been available to me: Brovkin, Vladimir in Soviet Studies, XL (1988), pp. 501–505Google Scholar; Cox, Terry in Revolutionary Russia, I (1988), pp. 119–123Google Scholar; Andrle, Vladimir in Social History, XIV (1989), pp. 409–411Google Scholar; Hagen, Von, Slavic Review (see note 26)Google Scholar; Koenker, Diane P. in The American Historical Review, XC (1989), pp. 1445–1446Google Scholar, and Merl, Stephan in Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas, NF XXXVII (1989), pp. 295–297.Google Scholar Cox and Andrle are more positive about Viola's book than I have been; the others, if anything, are more negative.

28 The most extensive statistics concerning labour turnover may be found in Filtzer, pp. 52–53. In 1930 the all-union turnover (discharges) amounted to 152.4% of the average number of people employed annually (1933: 122.4%; 1936: 87.5%).

29 This also goes for Kuromiya, , pp. 217, 290Google Scholar, Schröder, pp. 77, 289–291, 300–301.Google Scholar In this, Rassweiler, , p. 179Google Scholar, and Filtzer, , pp. 7, 49Google Scholar, hold a more balanced view.

30 The differences should not be exaggerated. In observing actual interactions both note comparable cases of collusive responses of workers and managers, as far as getting round the laws against unauthorized absenteeism was concerned (Andrle, , pp. 129–138, 200–201Google Scholar; Filtzer, , pp. 112–115, 236–243).Google Scholar

31 Filtzer bases his double categorization on letters written from the USSR to the Sotsialisticheskii Vestnik, and supplements these with reports from the Soviet press. His sources refer to a total of 25 strikes and other forms of collective resistance which took place between 1929 and 1934. But Filtzer's categories are mentioned explicitly in only two of the reports (pp. 81–90). Menshevik and Filtzer's Marxist prejudices converge when it comes to crediting ex-peasants with the capacity to learn new methods of struggle. Both believe that the peasant is incapable of useful social action without help from the urban proletariat.

32 Rittersporn sees similar effects in agriculture where, after collectivization, the harvest time doubled and yet the kolkhoz management attempted to reduce the level of compulsory deliveries. Rittersporn, , Simplifications staliniennes, p. 57.Google Scholar

33 According to Barber, John in Soviet Studies, XL (1988), p. 150Google Scholar, and Kuromiya, Hiroaki in The Russian Review, XLVII (1988), p. 199.Google Scholar

34 Here Siegelbaum takes issue (p. 298, n. 4) with Filtzer's view (p. 197) that “Stak-hanovism has done nothing to shake up the fundamental set of relations between managers and workers on the shop floor”. The polemic seems a little exaggerated because Filtzer is concerned here with deficiencies in the organization of work (supplies etc.). There is also less difference than Davies thinks between the conclusions of Siegelbaum and Filtzer concerning the disruptive effect that Stakhanovism had on industrial production (see Davies' review article, cited in note 13, p. 484).

35 As is well known, Soviet historians have, by and large, also left this version behind them since 1988. See the report of the Round Table on Collectivization, held in Moscow on 24 October 1988: Istoriia SSSR, 3 (1989), pp. 3–62, esp. 17.Google Scholar

36 Viola's chapter 6 “The 25,000ers at Work on the Collective Farms” has 106 notes, of which 10 refer to archives. Six of these serve, at best, only to reinforce what can be found in the printed sources; three relate to new data on the personal problems of individual members of the 25,000; one note relates to the shortage of animal feed in a particular region. None gives any information on the influence of the 25,000 on the progress of collectivization.

37 Berg, Ger P. van den, The Soviet System of Justice: Figures and Policy (Dordrecht, 1985), esp. p. 347.CrossRefGoogle Scholar Rassweiler is a victim of this phenomenon; for example, she mingles statistics on “workers and white-collar workers” with those on “workers” only (see tables 4 and 11, ch. 4; for her definition of labour force see p. 149, lines 23–28).

38 Until the law of 15 November 1932 it was possible for employers to dismiss workers who were absent without permission for at least three days in a month. The new law made it compulsory for employers to fire every worker who was absent without permission for even one day. See Filtzer pp. 111–112 and note 205.

39 The percentages were calculated every year by the statistical department of the Central Committee according to the level on 1 January. An overall party census was also organized on 10 January 1927, where the definitions which determined whether one was a worker, peasant, etc., were adjusted in order to make comparisons with the 1926 population census possible. This explains why the percentage of workers was 36.8% on 1 January 1927 and 30% on 10 January 1927 (Sotsial'nyi i natsional'nyi sostav VKP (b). Itogi vsesoiuznoi partiinoi perepisi 1927 goda (Moscow, 1928), pp. 1–51).Google Scholar Since the figures for the period 1928–1932 are given as per 1 January, Schröder's choice of the 10 January statistic for 1927 is misleading. See Schröder, H. H., Arbeiterschaft, Wirtschaftsführung und Parteidemokratie während der Neuen Ökonomischen Politik. Eine Sozialgeschichte der bolschewistischen Partei 1920–1928 (Berlin, 1982)Google Scholar, where, on p. 337, both figures for 1927 are given. For the adjustments of March 1927 and March 1928 see Rigby, T. H., Communist Membership in the USSR (Princeton, 1968), pp. 116, 161–164.Google Scholar