Introduction

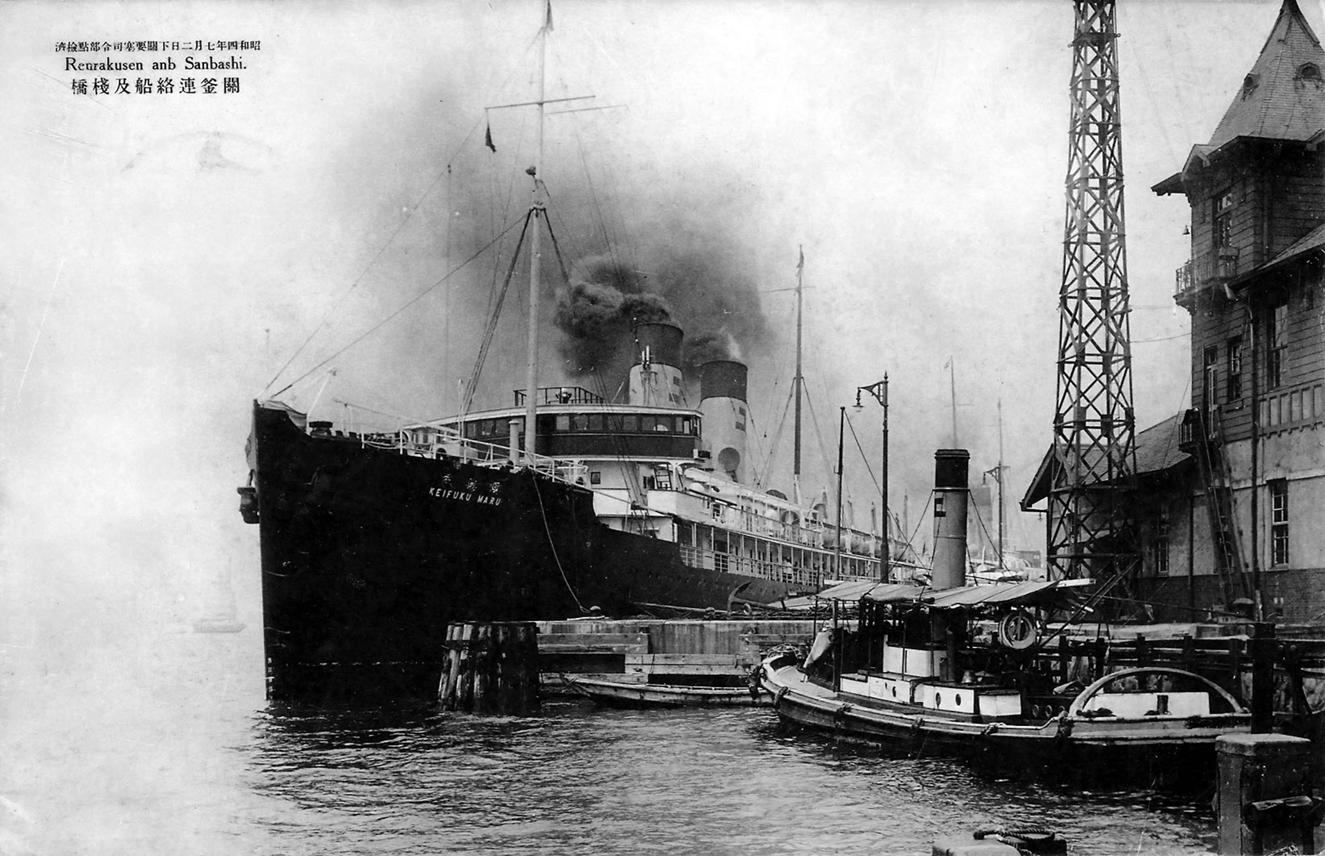

In April 1908, the Japanese periodical Railroad Review profiled a day of festivities in the Korean city of Pusan. There, workers had completed a final section of track connecting the occupied territory's main trunk line to the expanded harbor facilities at its southern terminus. According to the account in Railroad Review, the citizens of Pusan were ecstatic at the completion of the line. The journal's report began at the city's main station, where dignitaries gathered to send off a new express train to Seoul. Meanwhile, in the streets, members of the crowd indulged in refreshments while joyriders took short trips on the newly laid track. At the harbor, young onlookers in pleasure boats raced about as a recently launched ferry, the Ikimaru, docked beside her sister ship the Tsushimamaru (Figure 1). Finally, with evening nearing, the reader's focus was shifted from the harbor and the bright lights of the ferries back to Pusan station. There, the day's events were brought to a close with a lantern procession that marked the departure of a night train bound for Manchuria. The article ended with this striking parody of lights: two brightly illuminated processions, a line of humans and lanterns advancing in the darkness, mimicking the train as it proceeded northward away from the harbor.Footnote 1

Figure 1. The Tsushimamaru at sea.

Wikimedia Commons.

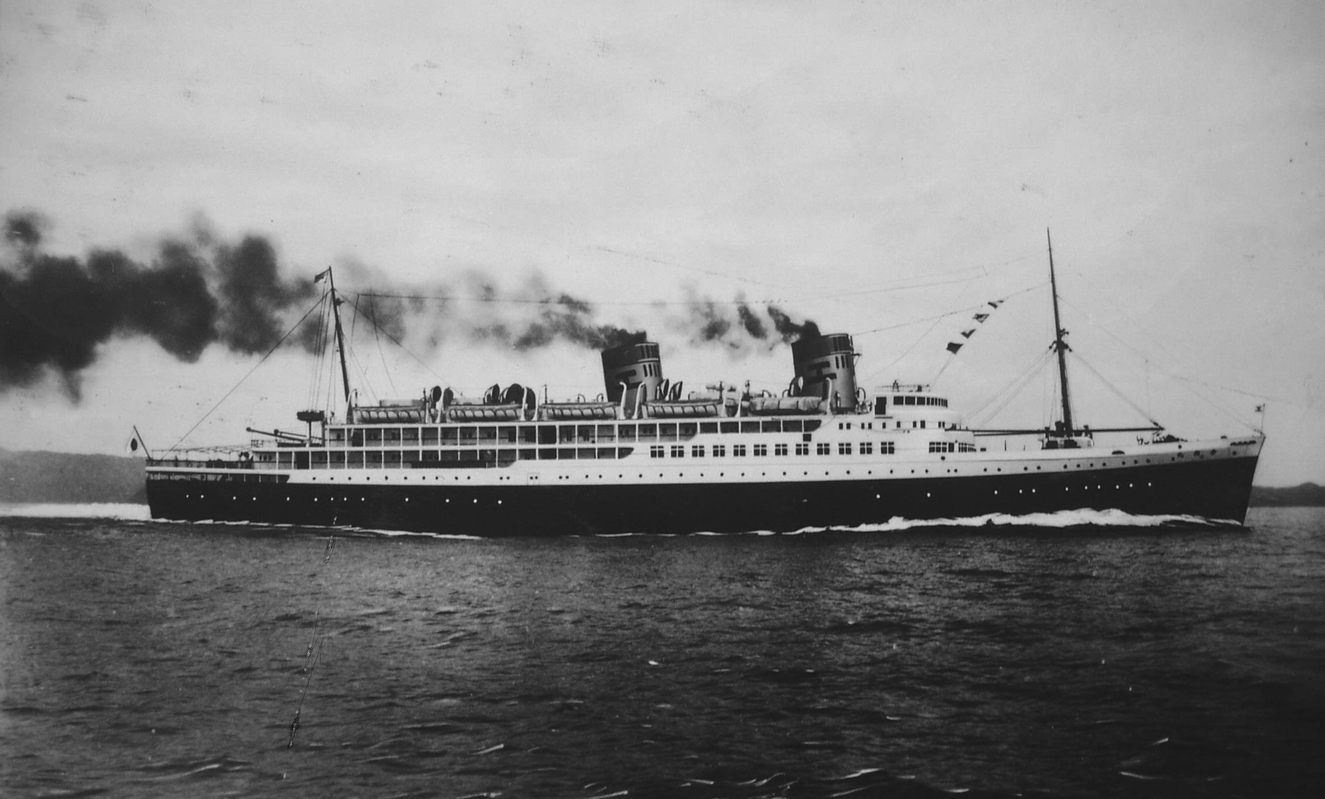

This was a celebration of logistics. According to the Railroad Review, fusing transportation infrastructure like the Pusan–Shimonoseki ferry and the Seoul–Pusan line promised to integrate constituent parts of a rapidly expanding empire. Over the course of Japan's occupation of Korea, the Pusan–Shimonoseki ferry stood as an iconic instance of such an integration, linking the archipelago to its colonial possessions on the continent. Over five generations of vessels traveled the line, each one larger and faster than the last. The ferry's first two Ikimaru-class ships weighed roughly 1,680 tons, carried 337 passengers, and could sail between Japan and the peninsula in just under twelve hours. Forty years later, the 7,900 ton Kongōmaru-class ferries relayed 2,050 passengers along the same course in just seven hours (Figure 2).Footnote 2 The line was never the sole route between Japan and the peninsula, nor the only one leaving from Pusan; but the ferry was always the most symbolic and widely used.Footnote 3 It was featured in poetry, became the setting for novels, and the stage for high-profile romantic death pacts.Footnote 4 The ships channeled a huge population of Japanese settlers to the continent, became a mainstay for the imperial tourist industry, and conveyed an entire generation of colonial students, soldiers, and workers to the metropole.Footnote 5 By the time daily service was suspended in 1945, the Pusan–Shimonoseki line had transported over thirty million passengers between Korea and Japan.

Figure 2. The Keifukumaru at the harbor in Shimonoseki.

Wikimedia Commons.

The rapid expansion of maritime lines like the Pusan–Shimonoseki ferry can easily be presented as part of a broader crescendo in a colonial relationship.Footnote 6 In the case of Korea, this is a story of ever-deepening ties that culminates in an active campaign of assimilation during the Asia–Pacific War.Footnote 7 However, a closer examination of transportation infrastructure also exposes the more textured dynamics at work in the story of imperial integration. Points of conveyance like the Pusan–Shimonoseki ferry played a dual role of transcending geographic boundaries while, at the same time, mandating new borders. The systems of travel registration and restriction that emerged alongside these increasingly large ships speak to this point. While the boundaries of the empire moved westward with each new generation of the ferry, they were also internally redrawn through shifting constraints on travel.

By focusing on the Pusan–Shimonoseki ferry, this study examines the effect of transportation infrastructure in shaping the movement of Korean migrants in the Japanese empire. In doing so, it also highlights the forms of resistance and control that materialized around these sites of transit. Throughout the first half of the twentieth century, underpaid Korean migrants were a vital part of the industrial labor markets of the Japanese metropole. Following a series of breakdowns in Korea's rural economy, a large population of displaced workers gravitated towards Japan. These migrants were at once a popular reserve of cheap labor and the target of racial discrimination and social exclusion. The border encouraged these attitudes in the metropole. The transportation infrastructure that connected Japan and Korea functioned to both depress the value of colonial labor and heighten the susceptibility of workers to managerial coercion and social subordination. To board the ferries, Korean migrants needed travel permits and employment contracts that deflated their wages, recorded their proposed residences, and stipulated the conditions under which they were to return to the colony. These requirements diminished the economic and social status of migrant workers in the metropole. Aware of these constraints, Korean migrants and labor activists attempted to mitigate their subalternity by asserting the right to travel freely.

This dynamic is explored through a collection of primary and secondary works on transportation infrastructure and travel policy in colonial era Korea. In particular, the article benefits from an edited volume on the Pusan–Shimonoseki ferry produced by Ch'oe Yŏng-ho, Park, Jin-Woo, Ryoo, Kyo-Ryul, and Hong Yeon-Jin.Footnote 8 It also draws from research on colonial Korean migrants and the politics of work in the metropole by Ken Kawashima.Footnote 9 More broadly, this study fits into a larger interest in the interconnected issues of migration, borders, and colonialism in East Asia.Footnote 10 For Korea, this scholarly focus has brought to light the fluidity of the peninsula's boundaries across the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.Footnote 11 It has also helped contextualize the persistent issue of interethnic relations in post-war Japan.Footnote 12

The early twentieth century was characterized by considerable shifts in the patterns of transnational maritime migration in different parts of the world. Many of these alterations were also reflected in colonial Korea through the forms of border control and conveyance that emerged with the Pusan–Shimonoseki ferry. For instance, scholarship on the history of migration in the North Atlantic during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century has emphasized the role of the steamship, analogous to those that plied the straits of Korea, in altering the paradigm of transportation. Steamships allowed more people to travel more quickly.Footnote 13 Importantly, they also eased repatriation when market conditions soured.Footnote 14 Attention to these dynamics has been part of a larger focus on the interplay between state and market formations in the channeling of maritime population transfers.Footnote 15 Of particular interest was the role of shipping agents and private firms in framing border controls and implementing systems of “remote control” over migration across the Atlantic.Footnote 16 Here, restraints on migration like registration and screening were displaced from the ports of entry to sites of departure and beyond. In this way, the border was dispersed across networks of transportation infrastructure.Footnote 17

The constraints on movement applied at the Pusan–Shimonoseki ferry reflect many of these same traits. In a version of remote border control, the Japanese colonial state employed several forms of travel registration to block migrants well before they reached the coast. That being said, the case of Korean migration to Japan differs from contemporaneous instances of population movements elsewhere in several important ways. In terms of actors, the major ferry lines to Korea were an extension of the Japanese Ministry of Railroads, and were far more reactive to state pressure than the private firms that dominated North Atlantic migration.Footnote 18 An additional difference is with timing. While much of the literature on population movements across the North Atlantic marks the year 1914 as a break from an earlier age of mass migration, in the Japanese empire, World War I stands as the starting point for a new chapter of expanded settler colonialism. Similarly, while studies from this period note the reframing of global migration as a question of national sovereignty, the realities of colonial relations prevented an analogous shift within East Asia until 1945. In contrast with the North Atlantic world, throughout the interwar period the multi-ethnic empire remained the most salient geopolitical unit in the region. It would not be until the aftermath of the Asia–Pacific War that newly established national boundaries would exert an analogous role in characterizing population movements between states.Footnote 19

Shaped by this context, this article focuses on the social implications of transport infrastructure between Japan and Korea, and, in particular, the forms of direct and indirect resistance that materialized in reaction to the influence that ferry lines exerted on migration. To do this, the discussion below draws heavily on colonial-era press produced on the peninsula, as well as a collection of works on migration published by the office of the Governor General of Korea (GGK). Although these materials display the curtailments of expression that defined the colonial era, they still offer an important window onto the prosaic character of the migration issue for those involved. When read against the grain, these sources offer important insights into the contradictions of colonial transportation infrastructure in an imperial market hungry for cheap labor.

During the age of pernicious colonial expansion that frames this study, borders functioned as essential forms of economic and ideological infrastructure that buttressed imperial hierarchies.Footnote 20 Commonly taken as simple demarcation points between polities, the ways in which borders take form through infrastructure can be obscured by their naturalization.Footnote 21 However, this study focuses on the capacity of the border as a mode of formation and interpellation that extends well beyond the geographic lines themselves.Footnote 22 More than simply a manifestation of nationalist ideology or an assertion of sovereign power, borders, like those that developed in connection with the Pusan–Shimonoseki line, exert influence through the legal and bureaucratic institutions that develop alongside.

In the case of the Japanese empire, the permits and documentation needed for movement, along with the costs connected with travel, effectively established a differentiation between imperial citizens within the social and economic realm.

This focus on internal borders is somewhat incongruent with the general emphasis on spatial amalgamation that informs accounts of the Japanese empire. However, as studies of the Korean diaspora in Japan show, intra-imperial integration did not result in the erasure of colonial difference.Footnote 23 For Korean migrant workers in Japan, an array of factors contributed to their sustained subalternity, which, in turn, affected their search for jobs.Footnote 24 Even when employed, they were subject to deflated wages, constraints on social benefits and housing, recruitment policy, and discriminatory hiring and firing practices. This paper approaches transport infrastructure and the borders it has helped to establish as an additional source of precarity. Onerous fees, a strict travel permit system, and the dangers of smuggling all worked to degrade a migrant's ability to negotiate the sale of their labor once in Japan.

Faced with these constraints, Korean workers developed a range of tactics to mediate the border and mitigate the effects of policies that depressed their place in labor markets. Confronted with intensifying rural poverty and a lack of economic alternatives, a subset of Korean labor activists even viewed unfettered access to job markets in Japan as an avenue by which to temper the ethnic-based exploitation of the empire. As discussed below, a similar stance was indirectly asserted by the thousands of migrants who smuggled their way to the metropole by way of informal passage. By taking control over how they traveled, workers and activists sought to mitigate effects of transportation infrastructure, which, by way of registration systems, turned the subordination of the colonial migrant into a precondition of departure.

Colonial labor and the industrialization of the metropole

Transportation infrastructure like the Pusan–Shimonoseki ferry facilitated a circumscribed form of integration within the Empire of Japan. For almost forty years, the line effectively connected industrial sectors in the metropole with the rural labor markets of its closest colony, Korea. This dynamic took form soon after the annexation of the peninsula in 1910. At this time, the Pusan–Shimonoseki line helped link two distinct transformations in the imperial economy. In Japan, a phase of rapid industrialization propelled by World War I was recasting labor markets and labor relations both. At the same time, on the peninsula, the completion of the colonial government's cadastral survey prefaced the emergence of a new population of migrant labor. Both ruptures were drawn together by transportation infrastructure; at the same time, controls enforced at transit points also set explicit terms for how Korean workers operated in the labor markets of the archipelago. Colonization opened the way for mass migration, but also cemented the subalternity of the migrant.

The end of the 1910s found the Japanese industrial sector in the midst of a rapid phase of expansion. Decreased production in a war-torn Europe, paired with growing domestic and regional demand for manufactured goods, resulted in a boom in production. Between 1914 and 1918, industrial output grew from 1.4 billion yen to 6.8 billion.Footnote 25 Similarly, in the six years after the outbreak of World War I, the number of factories on the archipelago increased from 31,717 to 45,806. At the same time, employment in this sector expanded from 948,000 to 1,612,000.Footnote 26 Under these conditions, manufacturers in the metropole turned to colonial migrants as an affordable solution to wartime labor needs.

A sequence of upheavals in Korea's agrarian economy left it uniquely positioned to resolve the metropole's demand for workers. The final decades of both the Chosŏn Dynasty and its short-lived cognate, the Empire of Korea, were defined by the breakdown of the peninsula's rural economy. Newly opened rice and commodity markets, peasant uprisings, anti-colonial struggles, currency alterations, and tax reforms all affected a population still concentrated in the countryside.Footnote 27 Compounding these transformations was the 1918 completion of a cadastral survey by the Governor General's Office of Korea and the Japanese-managed Oriental Development Company.Footnote 28 This project fully restructured how the peninsula's land was tabulated and taxed. Under the new model, informal practices of ownership were negated, and lack of title served as the basis for land dispossession. Similarly, the reassertion of state ownership over formerly royal holdings led to the eviction of thousands of farmers who informally worked these plots. For many more, dislocation from the land came gradually, with individuals uprooted as a result of more accurate and exacting forms of taxation or as the outcome of the expanded practice of land collateralization.Footnote 29

Under these circumstances, displaced peasants were left with few options. Some took to the hills to join a new population of slash and burn farmers. Many more moved to Manchuria or Siberia in search of new lands and livelihoods. For hundreds of thousands of others, the conditions of the colonial economy necessitated a relocation to the empire's industrial centers. For much of the colonial period, this meant the Japanese archipelago. While Korea's cities grew rapidly throughout the start of the twentieth century, colonial policy, particularly during the first decade of Japanese rule, curtailed the development of the peninsula's commercial and industrial sectors.Footnote 30 As a result, the metropole, in the midst of a wartime production boom, stood out as a singular option for Korean farmers searching for new livelihoods. These shifts can be traced in the abrupt expansion of the Pusan–Shimonoseki ferry. In 1911, just a year after annexation, the line conveyed roughly 2,500 Korean passengers to Japan every year. By 1919, that number had ballooned to over 28,000. Most of these individuals would return to the peninsula, but many remained. Figures produced by the Japanese Home Ministry indicate that, by 1920, the Korean community residing in the metropole numbered roughly 31,000.Footnote 31

While demand for migrant labor in the metropole varied, in the decades that followed the sustained impoverishment of the Korean countryside continuously replenished the pool of colonial workers drawn to the labor markets in Japan.Footnote 32 Border policy, enforced at points like the Pusan–Shimonoseki ferry, was among the best tools available to both configure and control this population. When the ferry was first established, Japanese migration policy was still guided by the Foreign Workers Exclusionary Law of 1899, which, with the exception of diplomats and students, restricted Koreans from traveling to the archipelago.Footnote 33 Formal incorporation of the peninsula into the Japanese empire in 1910 brought with it citizenship and the right of colonial subjects to travel freely. However, only one month after annexation, the Japanese Home Ministry began to exert greater oversight on the flow of Koreans. On the surface, officials expressed concern over a growing population of unskilled colonial workers. However, this sentiment was never clearly disaggregated from state anxieties over the inflow of foreigners, anti-colonial activists, anarchists, and unionists.Footnote 34

The needs of wartime manufacturing during the late 1910s often offset these concerns. The Korean labor that emerged from rural areas at this time was channeled through an expansive recruitment system geared towards the demands of the metropole's industrial and construction sectors. Under this regime, the Pusan–Shimonoseki line became the site where Korean workers were configured as an underpaid class of labor. Recruitment and terms of employment were set in the Korean countryside, but it was the potential for the denial of passage at the ports that helped enforce these inequalities. During the wartime boom, migrants were contracted for a time span of two to three years. Recruiting more than ten employees required pre-approval from colonial authorities and included contract stipulations about the type of work, hours, methods of payment and savings, expenses, travel fees, and approval for underage workers.Footnote 35 Later iterations of travel registration required migrants to demonstrate a sufficient degree of fluency in Japanese. Workers also needed to provide proof of employment and document savings sufficient for the price of a return fare.Footnote 36 A central part of this registration process was the setting of wages prior to departure. While subject to variation, GGK-issued wage charts encouraged pay rates anywhere from thirty to fifty percent lower than that of a Japanese worker.Footnote 37 Only after completing this process of negotiation and registration could migrants receive the documentation required by port authorities.

In spite of depressed wages, employment options and rates of pay remained for many migrants preferable to conditions on the peninsula.Footnote 38 Once more, even in its restricted form, the mobility afforded by colonial labor markets was a notable improvement over what a rural worker could have imagined just decades before. These considerations were further framed by the development of a permanent population of Koreans in Japan and the more flexible channels for employment that came into being alongside. Frequently, friends or family already in the metropole mediated positions for workers considering migration.Footnote 39 With this expansion of the Korean community in Japan also came opportunities for entrepreneurship, which, by the start of the 1940s, accounted for eleven per cent of the jobs held by Korean workers in the metropole.Footnote 40

During the first decades of Japanese colonial rule, the Pusan–Shimonoseki ferry brought together two entangled phases of economic transformation. On the peninsula, the colonial cadastral survey produced a new population of displaced workers. Drawn to the metropole, these migrants helped drive a wartime expansion of manufacturing and construction. The ferry helped integrate both of these transformations. Yet, at the same time, the geographic barrier of the straits allowed for state and economic actors to develop internal constraints on movement through terms of employment that were often precarious and undervalued. Failure to give assent to these conditions could mean the denial of passage, a phenomenon that became increasingly common as the wartime expansion of Japan's industrial sector concluded.

The borders of the empire

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, concern over the rapid growth of the migrant community in the archipelago, combined with an array of pejorative traits assigned to Koreans, stimulated a specific sense of alarm over the question of migration. This sentiment was captured through a perennial discourse on the “domestic migration problem” (naichi tokō mondai).Footnote 41 It presented Korean migrants as a threat to social stability, a channel for radical ideology, and a source of wage deflation. Fueling these concerns was the rapid growth of the Korean community in Japan. At the start of the 1920s, roughly 31,000 Koreans were residing in the archipelago. Within twenty years, the population swelled to nearly 1,190,000.Footnote 42 Such a rapid increase points to the extent to which the colony and metropole had become socially and economically enmeshed. However, also evident in this story of integration was a pattern of restraint and control. A system of travel screening and permits effectively formatted migrants and incentivized movement elsewhere within the empire. Operating as an instance of remote control over the border, these formations did not seal the metropole from the colony. Nevertheless, transportation-based restraints on migration still exerted considerable influence on the economic and social position of Korean workers headed to Japan.

The Pusan–Shimonoseki ferry was a primary site for the application of these constraints. A paper trail of documents delineated a migrant's journey to formal employment in the metropole, starting from the village and extending all the way to the factory gates. The ferry served as one of the best locations to screen these documents. Such travel requirements were part of a larger matrix of contingency that shaped the experience of Korean workers in Japan. From housing policy and arbitrary firings to bureaucratic intransigence and wage discrimination, colonial migrants were constantly confronted by everyday uncertainties that heightened their precarity in the market.Footnote 43 Workers certainly could cross to Japan without documentation, or violate the terms of their contract once in the metropole. However, in either case, their extra-legality in the market would be set.

Rules governing the migration of Korean workers went through several alterations over the course of the colonial era. However, the consistent requirement of documentation meant that restraints of some form were applied throughout the period. During the first phase of migration, in the 1910s, Korean migrants headed to the metropole had to produce police issued travel certificates that established the holder's identity, contracted workplace, and intended residence. These documents were inspected at the ferry docks where passengers were further required to pass a physical examination prior to boarding.Footnote 44 Starting in 1919, the end of the wartime boom and the outbreak of anti-colonial protests in Korea resulted in a strict curtailment of travel from the peninsula.Footnote 45 Shortly after, at the urging of the GGK, the entire model of migration control was loosened in favor of a “Free Passage” system. Then, just months later, in the wake of the Kantō Earthquake of 1923 and the frenzy of anti-Korean violence that followed, the Japanese Home Ministry again drastically restricted passage, going so far as to implement a program of migrant repatriation.Footnote 46

These oscillations in migration policy were framed by a consistent demand in Japan for cheap labor. Even the acute xenophobia that followed the 1923 earthquake could not lessen this common denominator. Reconstruction programs hinged on a steady supply of Korean workers and restrictions on Korean migration were loosened within months.Footnote 47 A marker of the importance of this source of labor can be seen in the growth of the Korean community in Japan, which had reached 120,000 by 1924.Footnote 48 Correspondingly, a much larger body of individuals was blocked from entry. Between just October and December of 1925, 145,000 migrants were denied passage at the Pusan harbor, swelling the city with workers.Footnote 49 To mitigate this backlog, in the summer of 1928 the Governor General's Office mandated that ferry passengers carry travel documents from their local towns.Footnote 50 The aim of this policy was to maintain the dispersal of workers at their locales, recreating the effect of a border across the districts of the peninsula. These policies considerably restrained formal access to wage labor in Japan, a fact reflected by the forty per cent drop in the number of migrants traveling on the ferry between 1925 and 1926.Footnote 51

In addition to these restrictions on transit, the colonial state also established new initiatives to redirect migrants within the empire at large. First developed in the late 1920s, these programs flourished in the early 1930s as both the global economic depression and a more aggressive strategy of imperial expansion came into being. Workers at this time were given administrative and logistical support to enter labor markets away from Japan.Footnote 52 In the colony, hydroelectric dam projects in the north as well as the development of irrigation and transportation infrastructure in the south were suggested in the press at this time as possible points of divergence.Footnote 53 Meanwhile, outside of the peninsula, the invasion of Manchuria in 1931 and the establishment of the Japanese-dominated state of Manchukuo in 1932, led to even more direct attempts to orient Korean migrants northward.Footnote 54

By the mid-1930s, this hybrid of restriction and redirection contributed to a marked reduction in the number of Korean passengers on the Pusan–Shimonoseki ferry. Whereas in 1933 over 146,000 Koreans took the line, the following years saw the number of passengers reduced to 107,000 in 1934, 83,000 in 1935, and 86,000 in 1936.Footnote 55 While passenger rates may have decreased, these figures belie other patterns of migration. By the early 1930s, a series of new ferries to Japan were established at multiple points in Korea. Moreover, along with the development of ever more stringent border regulation, migrants frequently avoided tabulation by turning to a range of informal modes of transport. This trend can be seen in the statistics generated in the metropole. While figures from the ferry suggest a reduction in migration, the Japanese Home Ministry recorded that, by 1936, the population of Koreans in Japan had grown to almost 700,000.Footnote 56

By the eve of the Second Sino–Japanese War, movement between the metropole and peninsula approached its peak. In spite of the measures of remote control meant to function as a border between the two regions, formal and informal travel became ever more common. Overcrowding of ships, especially at year's end, clogged the ferry lines and weather-related cancellations and delays resulted in huge backlogs that frequently brought disruption to the cities that anchored the line.Footnote 57 By the mid-1930s, additional ships were introduced between Pusan and Shimonoseki to help deal with the increased flow of people and goods.Footnote 58 With no reduction of movement in sight, occasional voices in the colonial press even circulated the idea of sidelining ferries altogether in favor of a suboceanic tunnel.Footnote 59

The steady increase in intra-state migration in the interwar Japanese empire ensured that the “domestic migration problem” remained a consistent point of public and state concern. Discussions on the topic shifted focus between local dynamics and transnational trends. For instance, a secret 1927 report produced by the GGK's Bureau of Police Affairs took the issue to be an expression of regional social conditions. Wartime production, the authors explained, followed by rumors of abundant positions, continued to attract Korean migrants. However, the workers’ lack of education, poor job skills and general precarity, left them vulnerable both to nationalist thought and to the appeals of socialist agitation. In turn, the report argued, migrants posed a specific threat to social stability.Footnote 60

Other voices were more willing to redirect the discussion of the “domestic migration problem” towards social critique. On the pages of interwar Korean newspapers, often peppered with accounts of the migrants’ trials, editorial sympathy was weighted in favor of the workers. Writing under colonial censorship, pundits used the topic to highlight the inequalities of an imperial system that allowed only some of the population to move freely.Footnote 61 Conscious of the dynamics connecting rural poverty, surplus labor, and the deflation of Korean wages in Japan, pundits writing in this vein frequently criticized descriptions of the migrant as aimless.Footnote 62 The problem of migration, the argument went, was more the fault of profiteering industrialists in the metropole and officials in the colony who neglected rural poverty. To some in the press, the problem of migration to Japan could only be solved by the economic enrichment of the colony.Footnote 63

Elsewhere, the interwar issue of migration in the empire was simply framed by transnational patterns. For instance, in a 1934 study produced by the Japanese Ministry of Colonial Affairs, border control was presented as part of a global trend towards greater state oversight on human and capital flows.Footnote 64 In this sweeping study, the migration legislation of multiple states was comparatively analyzed through the lens of post-World War I market dynamics. According to the authors of this work, border policy was a central tool for the state as it attempted to manage the heightened pace of global exchange.

Such comparative studies were attuned to a marked shift in transnational border policy that followed the end of World War I. Globally, states at this time began to gravitate towards greater control over citizens as a mode of exerting national sovereignty.Footnote 65 However, for polities oriented towards settler colonialism, this reorientation to the nation state was never as clear cut. The ambiguous status of imperial subjects in a pan-Asian empire like that of Japan, constantly complicated urges to consolidate the borders of the nation. A Korean worker might be viewed as a migrant in the metropole, but in Manchuria they were taken to be full-fledged members of an expanding power.Footnote 66 This uncertainty over the precise boundaries of the polity and its membership, internal to the logic of imperialism itself, frustrated the inclusion of the Japanese empire into the global trends of post-World War I migration policy.

Whether as an expression of a regional-specific phenomenon or a new global trend, writing on the interwar “domestic migration problem” converged on a negation of the colonial relationship. Authors attempting to frame interwar migration policy as a part of global trends passed subaltern subjects as foreign nationals and described provincial boundaries as sovereign borders. Even when the issue was framed as an outcome of market greed or bureaucratic neglect, suggested solutions focused on developing the Korean economy as though it could be desegregated from the empire. This explicit gradation of sovereign subjects and space was all the more astonishing given that Korea, unlike Manchuria, was specifically annexed by Japan. These realities ensured that decolonized renderings of Korean migrants as foreign would never correspond with the conditions at regional transit points like Pusan. Korean workers seeking passage to Japan were not outsiders within the empire, and the metropole was not some distant shore.

By some metrics, interwar statistics on Korean migration demonstrate the failure of the colonial state to control its “domestic migration problem”. The constellation of collateral, contracts, tests, and screenings that helped enforce a border between the colony and the metropole had clearly failed to bring an end to the mass migration of Korean workers. However, while the border never fully prevented movement, the formative function of the institution remained potent throughout the 1920s and 1930s. During this time, registration and screening systems demanded that workers submit to state and market concessions that hardwired terms of employment, and, more broadly, the status of their class as racialized subordinates in the metropole. The impact of this system was not lost on Korean migrants and activists at the time, and a politics of resistance quickly emerged to mitigate these constraints.

“We go on our own boats!”

The structures of migration control enforced at transit points like the Pusan–Shimonoseki ferry had two distinct outcomes for Korean migrants bound for Japan. For those able to acquire the correct documentation, migration policy ensured underpaid work for strictly delineated periods of time. For all others, the policies necessitated informal passage or the use of smuggling networks. As discussed above, the ebb and flow of Korean workers to Japan can be easily charted in the statistics produced by bureaucracies like the Ministry of Railroads.Footnote 67 However, these state records fail to capture the tens of thousands of workers who operated outside normative channels of transportation. Non-sanctioned migration was common, creative, and difficult for the state to manage. Equally political and practical circumventions, workers turned to informal migration to assert their freedom of movement and to enter labor markets with a greater degree of flexibility. Meanwhile, radical unionists on both sides of the Korea Strait took up the right to travel as part of a larger platform of reform.

By the late 1920s and into the 1930s, Korean migrants developed a number of informal tactics to mediate the border. At Pusan, harbor police overseeing the docks were frequently overwhelmed by the high volume of traffic. On any given day, and particularly at year's end, the city's piers and moorings were brimming with people, ships, trains, and cargo.Footnote 68 In instances when border controls were more stringent, the city became a bottleneck for thousands seeking passage to Japan.Footnote 69 Those unable to board the ferry had multiple ways to sidestep travel controls. Newspapers of the day reported on how workers stowed away in the coal hoppers and holds of freighters, or in the coolers and storage rooms of fishing ships.Footnote 70 In some cases, the more brazen would simply commandeer a vessel and set sail on their own.Footnote 71 Others mediated the border through the impersonation of registered workers or by purchasing forged documents.Footnote 72 Reports from the period suggest that these counterfeits were plentiful and relatively cheap.Footnote 73 For instance, in the spring of 1927, a raid on a printing house in Pusan netted thousands of fake travel documents. Stamped with the Harbor Office's official seal, the forgeries were priced at only five yen apiece.Footnote 74

These ad hoc arrangements could lead to unfortunate ends. Accounts in the colonial press of the day told of prospective travelers who would pay smugglers for passage only to find no ship at the embarkation point.Footnote 75 At sea, migrants were vulnerable to even greater risks. Passage to Japan was often done on small, overcrowded vessels that loaded and traveled at night.Footnote 76 Moreover, the smugglers’ lack of coordination with state officials left them exposed to the dangers of the passage. This could lead to predictably tragic results. In the winter of 1935, one capsized transport drifted for three days before its survivors were discovered.Footnote 77 Even more tragic events were common. In the fall of 1934, the Yonggunghwan capsized and sank in a storm while smuggling a group of migrants to Japan. Of the fifty-nine people onboard only five were rescued.Footnote 78 Again, in the winter of 1940, 130 migrants drowned when the Chiyŏng sank as it attempted a similar voyage.Footnote 79

Framed in part by this context, unionists in both Japan and Korea decried the impact that regulatory barriers and high transportation costs had on colonial workers. According to some in the labor movement, the best way to mitigate these systemic restraints was by further integrating the markets of the colony and metropole. For several years at the start of the 1930s, one organization in particular, the East Asian Transport Union, proposed to achieve these ends through a return to a system of “Free Passage” on collectively owned transport ships. Operating under the slogan, “we go on our own boats” this organization identified intra-imperial borders as a definitive feature of labor relations. According to activists connected to this movement, maritime transportation routes between the colony and Japan were a source of obstruction, not integration. Correspondingly, the easing of restraints on movement was held to be one of the best ways to deliver greater autonomy for workers in an empire-wide labor market.

These views guided the tactics and advocacy developed by the East Asian Transport Union. Formed at the start of the 1930s, the group linked migrant communities on both sides of the Korea Strait. Locally, the organization's stated aim was to undermine a transport monopoly held by two private ferry companies that operated between Jeju, a large island located to the southeast of the Korean peninsula, and the industrial hub of Osaka (Figure 3).Footnote 80 With deep roots in the migrant and activist communities of both of these locations, the East Asian Transport Union quickly grew to include almost 12,000 members.Footnote 81

Figure 3. Major colonial era sea routes linking Pusan with Shimonoseki and Osaka with Jeju.

Much of the group's efforts were focused on the localized issues of transportation costs and conditions. However, as the name of the organization suggests, the leadership of the East Asian Transport Union were also purposefully focused on the larger issue of migration in the colonial context. In one proclamation from 1931, a writer for the union decried the regional systems of migrant transit, noting that ferry companies in general mistreated passengers during voyages and extorted migrants with inflated ticket and shipping fees.Footnote 82 A union report from 1932 continued to highlight these regional issues.Footnote 83 The group called for the construction of better transport ships, reduced prices, and the protection of migrants from exorbitant costs. Centrally, the organization lobbied for the abolishment of border controls between the colony and the metropole, and, more broadly, the end to constraints on migration and discrimination based on nationality.Footnote 84

The East Asian Transport Union employed a number of tactics to achieve these aims. The group's 1932 report outlined a campaign that included literacy programs, the recruitment of ferry passengers, onboard performances, speeches, and targeted boycotts.Footnote 85 Building on these mobilization and outreach efforts, the group's most highly-profiled intervention came through the establishment of a collectively owned ferry line. In keeping with the organization's specific local goals, this union-run ferry was meant to help reduce the high costs of travel between Osaka and Jeju. However, the program also included designs to expand service regionally, with the stated aim of eventually replacing privately contracted transportation.Footnote 86

The initiative received generous coverage in the colonial press.Footnote 87 The East Asian Transport Union's development was closely charted and its ferry program in particular was praised as an instance of much needed Korean economic autonomy and collective action.Footnote 88 For instance, in an editorial column of the Oriental Daily News, one commentator asserted that the union was a fitting illustration of the broader economic awakening underway among migrants in Japan. The paper favorably likened Korean workers in the metropole to the German and Irish diaspora in America, or the overseas Chinese of Southeast Asia.Footnote 89 According to this appraisal, the union highlighted a new attentiveness to the power of collective action, which the editor took to be an avenue for economic renewal in the colony itself. This theme was reprised by the same column a year later when the paper pointed to the ferry union as an example of Korea's nascent maritime culture. Drawing parallels with the Phoenicians, the author suggested that the union was a prophetic manifestation of the peninsula's nautical and historical potential.Footnote 90

These evaluations were in striking contrast with the literature produced by the union. The organization's publications generally lacked the flourishes that characterized its coverage in the colonial press, but in important ways it was far more grounded. Glowing appraisals, like the ones offered by the editors at the Oriental Daily News, hardened a border between the colony and the periphery, and, in turn, the logic of the “domestic migration problem”. In such reporting, the East Asian Transit Union was singled out because of its apparent promise for the economic potential of the peninsula. By contrast, union writers generally avoided reductions of intra-imperial migration to zone specific concerns. For these activists, the presence of colonial workers in the metropole was an expression of an imperial economy, not an issue that could be reduced to the same borders that confounded the migrants on a daily basis. Rather than suggest that its tactics were part of a developmentalist intervention specific to the historical, geographic, or economic conditions of the peninsula, the East Asian Transport Union's politics highlighted the fundamental entanglement of colonial conditions and industrial markets. Union reports highlighted the connections between the exploitation of Korean migrants and colonial policies. Similarly, they stressed the relationship between the depopulation of the agricultural economy and the creation of a devalued market for temporary workers.Footnote 91 It was in part because of this history of imperial market integration that activists called for a return to the “Free Passage” system. For union writers, this was among the most effective ways to improve the status of workers who otherwise were compelled to occupy an economic role determined by their means of arrival. The unstated point of this final position, as well as of the analysis that informed such a conclusion, was that the “domestic migration problem” in the empire could only be resolved by redefining the scope of the domestic itself.

Smuggling routes and informal modes of passage allowed Korean migrants to bypass travel restrictions, but illegal migration did not prevent them from encountering the impact of transport infrastructure or the borders that they helped maintain. The documentation required for legal passage ensured that Korean labor in Japan would remain underpaid and precarious. For those operating outside of formal transportation routes, this exposure to the contingencies and exploitations of everyday life as a colonial migrant were analogous, if not even more acute. However, circumvention of transport infrastructure did allow for workers to exercise a greater degree of autonomy over the conditions of their lives. Moreover, as argued by voices of opposition like the East Asian Transport Union, rather than depend on the colonial state to resolve the issue of rural poverty, the interests of migrants would be better served by the dissolution of the structures at the border that codified them as precarious itinerates.

The end of the line

The onset of the Second Sino–Japanese War in 1937 and its expansion into the Asia–Pacific War in 1941 brought the Pusan–Shimonoseki ferry to a frenetic end. With the empire's transition to a wartime footing, earlier policies meant to regulate and restrain the flow of Korean labor to Japan were rapidly loosened. The National Mobilization Law of 1938, along with additional legislation the following year, eased restrictions on the movement of Korean workers.Footnote 92 By 1944, there were over two million Koreans in Japan.Footnote 93 Correspondingly, accounts from this time described the Pusan harbor as perennially crowded, with the ferry system struggling to accommodate the vast numbers of workers, conscripts, and general passengers traveling to and from the metropole.Footnote 94

Ships that serviced the line at this time bore the markings of the empire's militarization. Ferries were painted a bluish-grey to help camouflage them while at sea. On their decks anti-aircraft stations scanned the horizon for threats. The possibility of attack grew with the passing months and was realized with greatest loss on 5 October 1943, when one of the line's newest ships, the Kongōmaru, was torpedoed by an American submarine (Figure 4).Footnote 95 Regular operation of the ferry service between Pusan and Shimonoseki finally ended in June of 1945. Allied air raids, submarine attacks, and the planting of nautical mines in the waters around Shimonoseki forced the harbor and the ferry to cease operation. What remained of the line's ships was diverted to Fukuoka.Footnote 96

Figure 4. The Kongōmaru at sea.

Wikimedia Commons.

For four decades, the maritime transportation infrastructure that linked Korea with Japan played dual roles. While clearly a mode of territorial cohesion and spatial integration, ferry lines also helped demarcate a border between the metropole and its closest colony. For Korean migrants, this border turned travel into a process of configuration that heightened their precarity in the labor markets of Japan. The system of contracts, travel permits, and screening procedures that Korean migrants were required to mediate prior to boarding effectively formatted their position in the metropole. Such mechanisms delineated the peninsula and the archipelago even as annexation and ever-increasing rates of travel bound the two together. As highlighted in the sections above, elements of these bureaucratic barriers operated as a mode of remote control over the border.

Attempts to mitigate the effects of the border speak to the power of these formations. The widespread instances of non-sanctioned passage point to the continued willingness of migrants to exercise what agency they could over their movement in imperial labor markets. Similarly, unionist opposition to border controls imposed at the ferry routes clearly expressed an awareness of how the issue of migration was defined by the colonial context. For these activists and migrants alike, the “domestic migration problem” was an issue of intra-imperial borders and it would only be resolved when migrants were allowed to travel of their own volition.