INTRODUCTION: THE WIDF IN LATIN AMERICA

In the late 1940s, Vaillant de Couturier – the General Secretary of the Women's International Democratic Federation (WIDF), the most important communist-oriented feminist organization of the twentieth century – expressed a paternalistic, ethnocentric, and doctrinal attitude towards her Latin American colleagues before the executive committee of her organization.Footnote 1 The so-called egalitarian globalism of her feminist socialism masked her historicist and teleological understanding of women's liberation. Underneath it, she seems to have believed that there was one single path to achieving liberation, which could only be headed and disseminated by European communism, pacifism, and antifascism. In this way, the French leader obscured the long history of Latin American feminists, which was constructed in dialogue with crises and revolutions in their national contexts, and which laid the foundations for their adherence to and involvement with the WIDF. By contrast, this article argues that Latin American women did not just emulate the guidelines issued by the WIDF's European leadership in their struggles for liberation but contested and enriched them with demands rooted in their specific material reality. To make this argument, this article draws on case studies from the Cuban and Mexican chapters of the WIDF, as representative of socialist feminist organizations in Latin America during the early Cold War.

The Women's International Democratic Federation (WIDF) has been studied from various points of view and with various different methodologies. Kadnikova and De Haan analyse the content and proposals made at the WIDF's international congresses from the perspective of political history, giving preference to associations and meetings in Europe.Footnote 2 McGregor and Armstrong examine the WIDF's position and actions surrounding the process of decolonization in Asia,Footnote 3 while Gradskova has an understanding of the expansion of the WIDF's focus toward the so-called Third World, explaining the conflicts and clashes that arose in this process.Footnote 4 Some scholars – such as Yusta, Donert, and Goodman – examine the WIDF as a primary force in the creation of a female, antifascist, international human rights and peace movement.Footnote 5 However, despite recent research on leftist women's groups in Mexico, Chile, Brazil, and elsewhere, the exchanges between the WIDF's general secretary and the Latin American associations affiliated with it – as well as these association's participation in the international congresses organized by the WIDF during the early Cold War – have not received proper attention.Footnote 6 Studies of Latin American communist movements in the Cold War neglect Latin American women's associations and women within trade unions.Footnote 7 Some books focus on the links formed by Black international communism between the US and Latin America in the interwar period and on Black women's engagement in global freedom struggles.Footnote 8 However, the circulation and exchange of ideas between communist women in Latin American and Europe within the WIDF has not been significantly studied. Adriana Valobra and Mercedes Yusta's excellent book gives a broad understanding of the structure, militancy, and ideology of communist women linked to the WIDF throughout the continent. Departing from here, this paper seeks to shed light on the contributions made by its Mexican and Cuban chapters. It aims to decentralize the history of international feminist activism at the beginning of the Cold War.

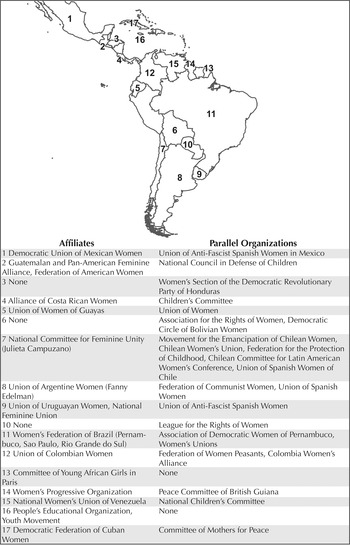

At the WIDF's Foundational Congress in November 1945, General Secretary Dolores Ibárruri – who was forced to leave Spain after the Civil War – explained the need to strengthen ties with Latin America. Representatives from Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and, forming a majority, Cuba and Uruguay attended this first meeting. Ibárruri announced that there would be more representatives from the region at the next congress. In fact, there was a special interest in incorporating Mexican activists as the Communist Party of Mexico was, by that time, a forceful entity.Footnote 9 However, the Mexicans did not send a delegation to the international congresses and conferences of the WIDF until the Copenhagen Congress in 1952. Shortly after, in 1956, a CIA report noted that several organizations linked to, or supporting, the WIDF had spread throughout Latin America (Figure 1). This confidential document reveals that the most important delegations came from Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, and Guatemala, though it notes that affiliated organizations also existed in less populated countries, such as Jamaica and British Guiana. The relevance of countries from the Global South to the WIDF rebalanced very significantly during the Cold War. Of all WIDF chapters, the percentage in Europe decreased from 47.1 in 1948 to 26.4 in 1975. In contrast, during the same period in Asia this grew from 21.6 to 23.6 per cent, in Africa from 13.7 to 23.6 per cent, in North America it fell from 3.9 to 1.9 per cent, and in Oceania it remained around two per cent. For its part, the proportion of Latin American sections skyrocketed from 11.8 to 22.6 per cent in the same historical period, it was the region with the highest growth within the WIDF.Footnote 10

Figure 1. According to the CIA, by 1956, the WIDF received extensive support from several communist, socialist, and left-wing women's organizations throughout Latin America. Among them there were two types of groups. The “affiliated”, which had requested to join the WIDF, and the “parallel”, that sympathized and helped the WIDF's national chapters. Likewise, women's groups supporting the WIDF turned up in countries such as Nicaragua or Peru in the following years.

Central Intelligence Agency, “Women's International democratic Federation (WIDF). A compilation of Available Basic Reference Data. Affiliates and Parallel Organizations, Strength, Officers, Addresses, Publicaciones”, 1956. Open access, https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP78-00915R000600140010-9.pdf

This article confirms De Haan's argument that the mutual, growing interest between the Executive Committee and Council of the WIDF and Latin American communist and socialist organizations was caused by a paradigm shift that took place between 1945 and 1948. However, clashes between the executive committee and the national chapters of countries in the Global South were especially bitter in the 1940s and 1950s, as Graskova argues.Footnote 11 The WIDF had been conceived during World War II, when defending democracy against fascism was its driving force. Once fascism was defeated, the political paradigm of the Cold War moved from democracy to anti-communism. Additionally, the movements for independence in Asia and Africa instilled in Latin American left-wing activists a renewed anti-colonial militancy against US foreign policy in the region. Fearing a conflict in Latin America, communist and socialist women began to position themselves against military escalation and the rising price of basic foods, and to argue for women's and children's rights. These paradigms and ideological positions were not just the result of top-down programmes established by the WIDF, but of very complex interactions between women's associations affiliated with the WIDF, and between these groups and the communist forces within their countries.Footnote 12

The Cuban and Mexican branches of the WIDF are fruitful objects of study for several reasons. Within the WIDF, they questioned, informed, and enriched global discussions about women's emancipation with disruptive ideas drawing on their specific material and political conditions. The complex and strained relationships between Latin American countries and the US concerning government institutions led Latin American leftist feminist militants to shape and share similar fundamental values and objectives. Communist Cuban and Mexican women both rooted their political discourses in similar nationalist revolutionary processes and in opposition to American imperialism and authoritarianism. Concerning women's political status – irrespective of when they gained the right to vote in national elections (respectively 1934 and 1953) – left-wing feminists from Cuba and Mexico were able to join and become militants in the WIDF in the context of a global Cold War. In addition, understanding the programmes and proposals made by Cuban and Mexican communist women at this time allows us to discover that “Latin American communist feminism” was not a consistent ontology. For instance, Cuban members of the WIDF emphasized the issues faced by Black women, while Mexican members barely mentioned the question of the diverse indigenous women in their country in publications and conferences.

This article takes as its object of study the activities of the National Bloc of Revolutionary Women (1941–1950) and its successor, the Democratic Union of Mexican Women (1950–1963) in Mexico, and the Democratic Federation of Cuban Women (1946–1956/61) in Cuba. It is commonly accepted that the WIDF displayed little interest in Latin America before the triumph of the Cuban revolution in 1959. But archival evidence suggests that a desire to strengthen political ties between leftist women from Mexico and Cuba and the Central Council and Executive Committee of the WIDF had existed since the foundation of the organization in 1945. From this date – instead of the European-based Council and Committee issuing top-down guiding principles and programmes to the Mexican and Cuban associations affiliated with the WIDF – fluent bottom-up proposals, initiatives, and petitions counterbalanced, enriched, and complicated the guidelines set up at the international congresses. The circulation of people, publications, and ideas between Latin America and Europe – together with those from Asian and African communist women – contributed to the creation of a truly transnational network of socialist feminism. The Eastern-bloc oriented WIDF focused on women's rights, peace, anti-colonialism, and children's rights, but its interactions with non-European activists brought decentralized, national perspectives into its discussions, which ultimately discredited allegedly universal assumptions concerning women's empowerment.

My research uses three main primary sources. First, the personal correspondence between the Executive Committee and General Secretary and the Mexican and Cuban representatives of the WIDF. Second, the minutes of the WIDF's international congresses held in 1948 (Budapest), 1953 (Copenhagen), and 1958 (Vienna), in which members of both countries delivered speeches and conferences on women's issues. And third, reports and letters published by Mexican and Cuban women in the English and Spanish version of Women of the Whole World, the main journal published by the WIDF. This information has been collected from the General Archive of the Nation in Mexico, the National Archive of Cuba, the Alexander Street foundation in Massachusetts (US), and the Historical Archive of the Spanish Communist Party. The theoretical frame applied to this analysis uses the postcolonial feminist perspective of Curiel (2009), Ochoa (2019), and Lugones (2020), which proposes that the study of feminist movements in Latin America for women's emancipation is a reaction against the combined sexual, racial, and religious norms and stereotypes that arise from postcolonial structures.Footnote 13

This paper first analyses the Mexican chapters and their relations to the Mexican Communist Party as well as to the WIDF. Secondly, the Cuban chapters are studied following the same structure. Finally, the conclusion gives some insights into the similarities and disparities between both groups of women to add further complexity to the idea of “Latin American women” in the WIDF, but also to re-evaluate their contributions to the federation.

MEXICAN WOMEN'S ASSOCIATIONS AFFILIATED TO THE WIDF

The two Mexican women's organizations affiliated with the WIDF after 1946 were the National Bloc of Revolutionary Women (BNMR, 1941–1950) and the Democratic Union of Mexican Women (UDMM, 1950–1963). Both were, to some extent, successors of the first nationwide women's federation in Mexican history: the United Front for Women's Rights (FUPDM). But, while the FUPDM was a broad front of left-wing, reformist, and Catholic women, the BNMR and the UDMM were organizations composed exclusively of communist women. The political plurality of the FUPDM in the 1930s was in line with the worldwide geopolitical pattern of Popular Fronts fostered by the Communist International (Comintern) during the interwar period, when progressive and nationalist forces sought alliances against the rise of fascism as a common threat. That historical moment coincided in Mexico with the presidency of socialist-sympathiser Lázaro Cárdenas Del Rio, who radicalized the revolutionary project embedded in the 1917 Constitution in 1934 (Figure 2).Footnote 14 Throughout the period studied in this article, the political influence of left-wing feminists in Mexico depended on the party discipline imposed by the presidencies of Lázaro Cárdenas Del Rio (1934–1940), Manuel Ávila Camacho (1940–1946), Miguel Alemán Valdés (1946–1952), and Adolfo Ruiz Cortines (1952–1958). The FUPDM was dissolved after the 1940 federal elections, when President Cárdenas backtracked on his promise to introduce an electoral reform allowing women to vote, even though this had already been approved by both Senate and Parliament. Mexican women did not gain the right to vote until 1953.Footnote 15 To some extent, both the BNMR and the UDMM tried to keep the radical legacy of the FUPDM alive in the early Cold War.

Figure 2. A group of militants of the United Front for Women's Rights (FUPDM) marching through the Zocalo, the main square in Mexico City, while waving banners of their organization. This demonstration took place in the context of the campaigns for women's right to vote under the government of president Lázaro Cárdenas.

National General Archive (Mexico), Photographic Collection, Enrique Díaz Delgado y García, Box 59/19. From Verónica Oikión Solano, Cuca García (1889–1973). Por las causas de las mujeres y la revolución (San Luis, 2018).

The BNRM joined the WIDF shortly after it was founded in Paris in 1945.Footnote 16 Established in 1941 as the women's section of the Communist Party of Mexico (PCM), shortly after the dissolution of the FUPDM, the BNMR was the most important left-wing Mexican women's association of the 1940s.Footnote 17 At the Second International Conference of the WIDF in Budapest, Madame Vaillant-Couturier presented an affiliation request from the “National Bloc of Revolutionary Women” for ratification by the general assembly; this was approved unanimously, although records show that collaboration payments from the BNMR to the WIDF had existed since 1946.Footnote 18 Both the BNRM and UDMM tried to preserve the political and social networks created by the FUPDM, and supported women workers and peasants through their contacts with existing rural women's leagues and trade unions.Footnote 19 Women on the BNMR national executive committee, some of whom had been FUDPM members in the 1930s, tried to keep the feminist programme of the Federation alive. For example, BNMR General Secretary Estela Jiménez Esponda, who headed the FUPDM education secretariat in the 1930s, unsuccessfully tried to counteract the influence of the Mexican Communist Party (PCM) and conserve the feminist programme of the FUPDM by putting gender ahead of class interests.Footnote 20 Adelina Zendejas, BNMR's Secretary of Press and Propaganda, had been an active syndicalist and supported José VasconcelosFootnote 21 in the 1920s, but joined the PCM in the 1930s. As well as managing the PCM's official magazine, El Comunista, she was a founding member of the FUPDM and campaigned for women's rights (Figure 2).Footnote 22 Another prominent member of the organization was Esther Chapa, the Secretary of Political Action. She spent her life balancing her political activism with her professional responsibilities as a surgeon at Juárez Hospital and a professor of microbiology at the UNAM. From the early 1930s she took part in the Sufragist Femenine Movement and the FUPDM as a strong advocate of separate jails for women in Acatitla. As a member of the PCM she defended both children's and women's rights. For twenty-two years, she asked the Congress to give women the right to vote every political term. But, in the early 1940s, Chapa moved away from the PCM to focus exclusively on women's issues. In addition, she got involved in the Mexican Committee to Aid the Children of the Spanish People.Footnote 23

Mexican women's emancipation was inextricably connected to deeper structural reforms. It is no coincidence that the letters and reports sent to both the federal government of Mexico and the WIDF by the BNMR were signed with the slogan, “For the liberation of women and for the progress of Mexico”. BNMR petitions in 1946 called for female suffrage and equal rights for men and women, but the organization also campaigned for women's rights in employment, welfare, education, and associational life. These campaigns were influenced by the broader movements of Latin American women, within the Inter-American Commission of Women, which pushed for women's rights as human rights in the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948. In addition, the Organization of American States, encouraged by the IACW, passed two conventions encouraging governments to ensure that civil and political rights for women were constitutionally guaranteed.Footnote 24

Correspondence between Mexican representatives of the BNMR and the WIDF Secretariat in Berlin demonstrates how Mexican women sought to insert their specific concerns into the WIDF's political guidelines on women's rights, world peace, and child protection. The WIDF guidelines largely dictated the topics of BNMR meetings, as illustrated in a letter from Esthela Jimenez to Marie-Claude Vaillant-Couturier. Jimenez wrote that Mexican women were organizing “the National Assembly of the BNMR with representatives coming from every state of the country. The fundamental problems of Mexican women (economic, social, cultural, and judicial) will be discussed, and the problem of Spain, the one concerning Greek women, etc. […] in accordance with the instructions you gave us in your notes and circular letters”.Footnote 25 However, at the same time, the BNMR also raised their own specific concerns stemming from the Mexican and Latin American contexts. In 1946, Esponda sent a report to the WIDF defining Mexico as a “semi-feudal” and “semi-colonial” country, indicating a primary aim to fight for national liberation and economic independence. She emphasized the BNMR's opposition to the right-wing Mexican groups Synarchism, National Action, and Spanish Falange. In the same way, she pointed out that Truman's foreign policies posed a serious threat to the independence of Latin America and, more concretely, of Mexico. Moreover, Esponda let the WIDF know that the BNMR had approximately 30,000 members and that they were committed to the fight to improve the living standards of Mexican people, with a focus on children and women.Footnote 26 The exchange of information, activities, letters, and reports shows a desire to be connected and to make the basic shared feminist agenda set out by the WIDF more complex by adding the national viewpoints of women from different parts of the world.

To translate the WIDF's international agenda into the national arena, the BNMR developed a complex propaganda apparatus of meetings, articles, brochures, and radio broadcasts.Footnote 27 For instance, in December 1946, the BNMR organized a national assembly gathering approximately 300 representatives from women's associations in several states of the nation.Footnote 28 This paved the way for a Mexican Women's Unity Committee.Footnote 29 The BNMR's political position towards the peace movement embodied the guiding principles of the Mexican Communist Party.Footnote 30 In the frame of these political connections, the BNMR's members organized several international campaigns at a national level, such as the Childcare Week and the International Day of Women, among others.Footnote 31 Notably, they established the need to consolidate democracy in order to fight fascism and stop it spreading throughout America and into Mexico. The BNMR was committed to the anti-authoritarian fight inside Spain, and supported anti-Franco guerrilla warfare.Footnote 32 The organization tried to gain sympathizers for that campaign by strengthening the coordination of its regional branches through internal circular letters. In this correspondence, the executive committee wrote that “all of us can do anything in favour of the Spanish detainees. A letter, a protest, a visit to consulates, talk about the problems in assemblies and rallies, in union and popular meetings, make our people feel this question helps save one of those lives that is in danger”.Footnote 33 Likewise, the BNMR tried to support the clandestine fighters in Spain by sending products such as clothes and food to finance an international lottery promoted by the left-wing French Women's Union in 1946.Footnote 34

The BNMR also took part in the First International Congress of Women organized by the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom in Guatemala in 1947. In this meeting, the BNMR's representatives advocated for a strong position against arms race escalation and in favour of human rights, and the approval of migration laws in relation to war victims from Europe. Coupled with this, they emphasized the need to enforce equality in the civil and political rights of men and women and the right of women to hold leadership positions in their respective governments. At the end of the congress, the Mexican delegation backed the final communication in favour of building an enduring peace process in the world.Footnote 35

The archival documentation shows that the BNMR kept the WIDF informed about their activities supporting women and reported to the WIDF general secretary on the main conclusions of their national assemblies. For example, in November 1946, representatives from all the Mexican states met in Mexico City to discuss social issues concerning women: their participation in the industrialization of the country; their fight against low standards of living and the high price of basic products; their demands for clean, affordable, and hygienic accommodation; the necessary cultural improvement and participation of Mexican women in the civic life of their country; equal rights with men, and other topics. The BNMR also reported that they were to open canteens, refectories, and small first aid centres for the unemployed and people with no financial assistance, and that they had made donations to a Rehabilitation Bank so that the BNMR's affiliates could invest substantially in low-price houses. Likewise, the association promoted a periodic craft fair selling objects made by women members from the regional branches, with the proceeds of the sales going to the craftswomen.Footnote 36

The BNMR's position was strengthened and its activity throughout Mexico increased – alongside its capacity to follow the WIDF's guidelines – after the transition from Manuel Avila Camacho's government (1940–1946) to the presidency of Miguel Alemán Valdés (1946–1952).Footnote 37 As a result, the BNMR were able to support other Mexican women's associations. In the Mexican Valley, they helped some members of the Liga Femenil Eufrosina Camacho Viuda de Avila, who were at risk of losing their homes, by intervening with the ruling party to secure land properties for them in Ixtacalco. Likewise, they helped the Federación de Organizaciones Femeninas in Yucatán to create protective homes for women in Merida that provided reading clubs, training centres for sewing classes, and services such as childcare and maternity centres.Footnote 38 In the north-western state of Sinaloa, almost 200 small women's organizations, which had already been created under the FUPDM in 1937, sought the support of the BNMR executive committee in Mexico Federal District. They needed to request a loan from the Federal government to set up houses for women social workers to strengthen their technical skills and for other urban improvements, such as hospitals for children, maternity centres, and mills to grind maize for “tortillas”. Sinaloan women also requested some “communal sewing shops and technical schools in which peasant women learn to make their family's clothes and obtain additional income for the same family by selling cheap clothes”.Footnote 39

Women affiliated with the BNMR did not aim for political rights alone, but for technical knowledge to gain economic independence and to enforce “the revolution turned into a government”.Footnote 40 Regional associations gave women the opportunity to deliver joint proposals and leapfrog state organisms by using civic platforms such as the BNMR to intercede with federal institutions. Women of the BNMR were able to exploit the language of the Mexican Revolution itself and to align with its objectives to obtain some benefits for women, and for their relatives and neighbours.

In accordance with the gendered preconceptions of both the WIDF and the PCM, the BNMR suggested ways to boost women's autonomy without completely breaking traditional gender patterns. Within the conservative paradigm of maternity promoted by Manuel Ávila Camacho, the BNMR sought to extract feminist emancipatory potential from women's traditional daily duties and expertise. During World War II, the BNMR claimed that “democracies must achieve an improvement in the life of the people, because otherwise fascism will always find a fertile ground for hatred and violence”. In that context, women had to assume two maternal roles: mother of their biological children and symbolic mother of the sons and daughters of the nation. The BNMR's General Secretary, Jiménez Esponda, stated that women disproportionately struggled with social problems because of their responsibilities for housework and childcare. As most Mexican women had to fetch water for washing and cooking, Jímenez Esponda claimed, improving water provision in towns and cities would reduce the need for them to use natural rivers or pumping wells water sources. Since women prepared and cooked tortillas, the BNMR argued that providing nixtamal mills would help free them from some of their gendered responsibilities, allowing them to spend more time on personal development.Footnote 41 And, finally, better medical infrastructure would reduce the amount of time women spent at their nearest health centre.

To overcome some of these constraints, the BNMR and the female section of the PRM promoted schools of Domestic Economy and Social Work for women. If the “domestic economy” reinforced links between women and duties such as managing the family's income and expenses, “social work” described the care work that women undertook because of a presumed natural impulse. However, placing due emphasis on these gender-biased but technical skills by asserting their benefits to the whole of society meant the BNMR elevated the importance of a women's professional trajectory, redirecting its place in society in line with the PRM's political philosophy concerning women.Footnote 42 The BNMR encouraged the government to create schools for domestic sciences, small-scale industries, technical training, and social assistance schools for women workers, old age and children's homes, as well as credit unions for farming chickpeas, sesame oil, tomatoes, and corn. More specifically, they requested state economic support to help them open communal factories and markets for women to sell their hand-made textile products. This initiative led them to envision and create new ways for women to achieve economic empowerment in rural and local areas.Footnote 43 To sum up, although they kept within the limits of women's normative roles in the public sphere, these initiatives met the WIDF's objectives of empowering women as well as the state's directive to further the progress of the country, a motto of both the PRM until 1946, and the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) since then.

During the Ninth Congress of the PCM in 1950, the UDMM replaced the BNMR as the main affiliate of the WIDF in Mexico, taking on the responsibility of implementing the WIDF's aims: to fight for peace and against imperialism; for women's civil and salary equality; for women's labour and trade union rights; and for children's rights. The executive committee of the UDMM attempted to adopt a multi-ideological militancy – like the FUPDM had in the interwar years, when the Popular Fronts policy fostered by the Communist International had made that stance easier. However, the rise of the PRI at the expense of the PCM in the early Cold War affected the political capacity of the women's section of the communist party to recruit members from other political backgrounds or with no political position. The PCM's directive board seems to have been more concerned with the triumph of the proletariat and ultimately the establishment of a communist society. The Twelfth Congress of the PCM in 1954 noted that the core number of communist women in Mexico was very small and that the organic structure of the party lacked female cadres. Nonetheless, according to the CIA – which was closely tracking communist political activism in America by the early 1950s – the UDMM maintained several branches throughout most of the states of the Mexican Federation. Mexican women affiliated with the WIDF were strongly committed to the international human rights and the peace movement, and the need to improve women's living conditions and political status at the national level. Esther Chapa was very influential, nationally, but the UDMM's most prominent leaders before the WIDF were Mireya B. de Huerta, Paula Medrano, Paula Gómez Alonso, and Socorro Burciaga. Despite the PCM's lack of support, the UDMM attempted to meet the instructions of the WIDF and attracted women into its structure. To do so, the UDMM increased propaganda efforts, enhanced cooperation with trade unions, and brought the worries of common people into their regular meetings, giving priority to women's problems.

The UDMM had stronger and more extensive links with the WIDF than the BNMR. These links proved increasingly important during the 1950s as the conflict between capitalism and communism escalated, exerting influence on the Latin American region, especially after the US-supported coup d’état in Guatemala in 1954.Footnote 44 At the Third International Congress in Copenhagen in 1953, UDMM representative Paula Medrano stressed the involvement of the organization in the opposition to imperialism inside Mexico and imperialist agreements between the Mexican and the US governments. American imperialism, claimed Medrano, threatened to destroy Mexican sovereignty and independence. To face this international threat, the UDMM opposed the mobilization of Mexican soldiers in the US-led invasion of Korea. Mexican women ultimately made the government interrupt these negotiations with the US. Shortly afterwards, the UDMM created the Female Committee for Guatemala in response to a global military escalation and an increasingly aggressive US foreign policy in the region. This committee gave political asylum to people fleeing the country after the US-led military invasion. In her speech to the WIDF Copenhagen conference, Medrano also drew attention to the specific problems faced by Mexican peasant women. For instance, in the Lagunera region, between Coahuila and Durango, many peasant men migrated to the US due to a lack of water and the scarcity of national credits in the region to secure their jobs. She explained that the “women tried to save their land by drilling wells. They formed committees and applied to the Collective Bank for Peasant Communities, to the Department of Agriculture, and mobilized other women, with the result that the wells are drilled”. She also explained that the UDMM had agreed with the Association for the Protection of Children to set up crèches and schools in working class neighbourhoods, holiday camps and open-air schools for tubercular children, and medical services for infant and children of school age. In so doing, the UDMM implicitly sought to follow the PRI's national project of modernization, as well as the WIDF's global agenda for women's and children's rights.Footnote 45

The following year, Elvira Trueba was the Mexican representative at the Fourth Congress of the WIDF in Vienna. Although she was not a communist or a member of the UDMM, Trueba had been one of the few women representatives of the trade union of the Mexican National Railway since the 1920s and an active antifascist activist in the Union of American Women, created in Mexico in the 1930s. In Vienna, she addressed the existing differences between men and women, despite the fact that Mexican women had been enfranchised for five years, and stressed that her organization – also linked to the WIDF – was pushing for the abolition of any discrimination against women, especially salary inequality. In her speech, Trueba emphasized how the “social services developed by women's organizations, independently of the one attended by the State, aimed to solve the problems affecting women, children, and elderly people”. She also affirmed that left-wing women were pushing the government for an increase in teachers’ salaries, the expansion of the primary education system, and for training centres where women could improve their technical skills and become more competitive in the labour market.Footnote 46

The UDMM broke with the Mexican Communist Party in 1964 and was re-established as the National Union of Mexican Women (UNMM), which began a new period of Mexican women's activism closer to the New Left.Footnote 47 At the Sixth International Congress in Helsinki, 1969, the General Secretary of the WIDF, Cecile Hugel, noted that Mexican and Chilean women had led the Latin American mobilization for women's rights in the continent during the 1960s. Hugel specifically remarked on the success of the Seminar on “the defence of the rights of women and children to life, well-being and education” convened by the WIDF in Mexico (22–25 July 1968) with the financial support of UNESCO.

The report also noted that the UNMM, its president, Marta López Portillo de Tamayo, and its honorary president, Clementina de Bassols, “stimulated considerable activities throughout the country on the preparation of the meeting”. Most significantly, the WIDF acknowledged that Mexican women made “an important and specialized contribution to the enrichment and approval of the studies already existing on the status of women and children; they also resulted in a deeper knowledge of the international documents of the UN and its specialized bodies”. The WIDF was confident that its network of contacts and meetings “made it possible to emphasize the universal nature of the (women's) problems to be resolved”, but it also indicated “the need for wide discussions of them”. The WIDF's assessment implicitly recognized the need to keep working, but showed that it had listened to left-wing Latin American, African, and Asian women, whose contributions were key to challenging the assumption that women's problems around the world mirrored those in Europe.Footnote 48

However, as we will see in the following pages, the FDMC had a greater presence, influence, and autonomy in the domestic political scene than the BNMR and the UDMM. This could be explained by three factors. Firstly, the Mexican organizations were subject to a corporative state that excluded communist forces from government once the revolutionary period led by Lázaro Cárdenas in the 1930s had ended. Secondly, given the corporative nature of the state, national women's organizations in Mexico were diverse, comprising left wing, reformist, and even conservative women. This made it very difficult for members to reach unanimous decisions. And, thirdly, after Cárdenas left office and the FUPDM was dissolved, communist women lost influence within women's state-sponsored organizations, which made it more difficult for them to bring their ideology and objectives to the fore in international meetings.

THE DEMOCRATIC FEDERATION OF CUBAN WOMEN (FDMC)

In 1945, a Cuban delegation attended the founding meeting of the WIDF, which included Uldarica Mañas and Herminia del Portal (both from the Lyceum), Mercedes Alemán (Office for Children's Defense and Protection), Dolores Soldevilla (Female Service for Civil Defense), and Nila Ortega (Confederation of Cuban Workers). One year later, Ortega and Soldevilla wrote to the WIDF in Paris to explain that it had not yet been possible to create a national organization of progressive and leftist Cuban women, but that they were committed to doing so in the short term; they had already arranged several events to raise feminist awareness and explain the WIDF's political programme.Footnote 49

Almost 200 women established the FDMC on 15 November 1948 in Havana. From that time, it operated as the Cuban branch of the WIDF and, to some extent, as the women's section of the PCC. Its founding document declared adherence “to the Women's International Democratic Federation established in Paris (France) in December 1945”. The FDMC aimed to organize women as workers, peasants, and liberal arts and domestic workers regardless of race, religion, or political affinities and to fight for real equality between men's and women's rights in every social, economic, and legal realm. The document also embedded both the WIDF's and the PCC's programmatic objectives, such as the improvement of Cuban citizen's living conditions, state-funded social assistance services, and a labour insurance system.Footnote 50 Some of these ideological assumptions drew on the political background of its executive committee. For instance, Esperanza Sánchez Mastrapa had taken part in the Third National Congress of Women in 1939, which had been the first to organize a round table on Black women's experiences; and Clementina Serra and Nila Ortega had organized the Provincial Association for Women's Popular Education. Both García Buchaca and Mastrapa were also members of the PCC, while Ortega was an appointed representative of the Confederation of Cuban Workers. Some of the PCC and FDMC leaders were also personally connected.Footnote 51

Cuban women had been enfranchised in 1934; the law that passed their right to vote was ratified in the new democratic Constitution in 1940, much earlier than Mexico (1953). A liberal feminist movement had emerged in Cuba between 1912 and 1917. It was strengthened in the 1920s owing to the two national congresses organized in 1923 and 1925. During that decade, a progressive political shift occurred within Cuban civic society. Mass organizations such as the National Confederation of Cuban Workers, and political parties like the Cuban Communist Party (PCC) were founded. After a moderately democratic term, General Gerardo Machado established an authoritarian regime between 1928 and 1933. Under his presidency, the feminist movement split into two main factions: moderate feminists demanding the right for women to elect and be elected; and radical feminists who considered the measure “stale from the source” in a non-democratic regime, and demanded deeper changes in the political structure to grant women's full emancipation.Footnote 52 Among these women, some were socialists and communists affiliated with the now clandestine PCC, such as Ofelia Domínguez Navarro: founder of the Labour Women's Union and the Radical Women's Union. Shortly after, in 1940, a more democratic constitutional text was approved because of the work of several grass-roots assemblies – including the III National Congress of Women – and the increasing circulation of international ideas during the early Cold War, which claimed women's rights were human rights and significantly reshaped feminism in Cuba.

Once suffrage was approved, according to Michelle Chase, the feminist movement did not disappear, but moved from liberal to socialist and communist principles.Footnote 53 The PCC once regarded moderate feminists as bourgeois, as they exclusively focused on gender issues and overlooked the class constraints affecting female industrial and domestic workers. Communist women gained influence in the PCC from the 1930s onwards, when the party created female sections in their youth wing and trade unions and selected women as Parliamentary candidates.Footnote 54 In the 1940s, female candidates for the Autentico and Republican parties obtained, on average, five per cent of the votes, while women of the PCC received up to twenty per cent in 1944.Footnote 55 Women lacked influence in mid-century Cuban state institutions, but wielded power in civic society as feminist activists. While long-lasting and well-known women's cultural associations – such as the Lyceum and Lawn Tennis Club – still existed in the early Cold War, the most important Cuban women's feminist organization in the 1940s and 1950s was the Democratic Federation of Cuban Women (FDMC).Footnote 56

The FDMC achieved influence among Cuban women because of its extensive structure. It existed on national, provincial, and local levels, and was made up of different social classes, faiths, and “races”, unlike other female white-collar associations. Within the lowest ranks of the organization, management committees integrated by women workers represented several industries, such as tobacco, sugar, telephone, laundry, and ironing. Domestic workers, who did not have the right to unionize – in contrast with industrial and commercial women workers – were also represented. Like the BNMR, the FDMC had its own journal, Mujeres Cubanas, but the Cuban group also regularly published a column in the national newspaper, Noticias de hoy, as well as broadcasting regularly on the radio, which increased its ability to reach a broader audience in the countryside.

FDMC members’ commitment to the fight against racism in Cuba was unique among Cuban women's organizations, and very innovative even within the WIDF. For instance, one of the leaders of the organization until 1951, Sánchez Mastrapa, highlighted the failure of the new Cuban Constitution to erase the enduring racial boundaries that excluded most women of African descent from better living and labour conditions. At the Second International Congress of the WIDF in Budapest, Mastrapa emphasized the tripartite oppression of Black Cuban women “500,000 coloured women in our country hope that this great Congress pass resolutions tending to fight against discrimination wherever it exists as a part of the struggle to establish true democracy”.Footnote 57 Statements like this were repeated at the FDMC's national congresses and local assemblies. In this way, the organization raised awareness, both inside and outside the island, of the problems that Black and mulatto Cuban women faced in their daily lives.

However, according to scholars such as Mackinnon and Chase, the FDMC did not meaningfully challenge the gender gap in labour markets or succeed in depicting the family as the basic mechanism blocking women's emancipation. Their demands were focused – in order of importance – first on class, then on women, and then on race. In other words, this organization asked for better labour conditions for working families, addressed the position and rights of women workers, and, occasionally, demanded that men and women workers’ opportunities were placed on the same level regardless of race or perceived phenotype. However, the FDMC demanded, with little success, that the international agreement on “equal salary for equal work” be enforced at a national level. This was eventually signed into law by the Cuban government once the International Labor Organization passed it in 1951.

Not surprisingly, the demands formulated by the FDMC in relation to women's emancipation and international peace were portrayed as a necessary precondition for children's rights. Alongside groups in the so-called first wave of feminism – and in line with the WIDF's political programme – the FDMC proposed several measures to ensure good living conditions for Cuban children once World War II had ended. The threat of nuclear war strengthened their commitment to peace, and to women and children's safety. The FDMC arranged a national conference on this issue and some of its members, such as Esther Noriega, took part in the Childhood World Congress in 1952. Prior to this international meeting, attendees discussed issues such as the main causes of infant mortality, childhood diseases, solutions to rates of childhood illiteracy, and regulations for existing child reformatories.Footnote 58

The political and gender discourse of the FDMC helped to redefine the image of women as “new women”, in fact, as “super-women” avant la lettre: able to juggle jobs and “their” housework. As opposed to the “female literature” focused on women's beauty and entertainment that was represented by journals such as Vanidades, the FDMC-funded Mujeres Cubanas defended the emancipation of women by increasing their literacy rates. In the late 1940s, the organization helped set up a night school, so that women workers could study after their working day. According to Chase, the FDMC revolutionized the gender/class divide in Cuban society by suggesting that women workers and peasants should be incorporated into political networks of solidarity and activism outside the fight for women's rights. For the FDMC, women's emancipation was mainly subject to the power relations structuring and sustaining class relations.Footnote 59

As for its international militancy, the WIDF appreciated the FDMC's actions concerning the civil defense of Cuba in the face of the expected war between the USSR and the US, and its support of the clandestine groups opposing the Franco dictatorship in Spain.Footnote 60 At the Second International Congress of the WIDF in Budapest, García Buchaca, a Cuban representative, emphasized that “submission to the interests of imperialism is the way to war. […] And each step towards war will bring, as an inevitable consequence, less democracy”.Footnote 61 In that sense, the onset of the Korean War made all women more aware of the need to demand rights and provide protection for children affected by military conflicts. Following WIDF and PCC guidelines on the international context, the FDMC's leaders launched a high-profile campaign for nuclear disarmament and against President Prío Socarrás's decision to support the US by sending Cuban soldiers to the Korean War. According to the FDMC's official magazine, the organization managed to collect up to 700,000 signatures against the president's project, which was finally discarded. Likewise, the Cuban Mothers’ Commission for Peace, encouraged and supported by the FDMC, wrote to Socarrás seeking this annulment. In this letter, they wrote “Mr. President, it is our children who are going to die if you send them to Korea”.Footnote 62 The reaction of Cuban communist women and mothers to the Korean War and the potential involvement of their colleagues and children in it enacted a maternal feminism that regarded global peace, anti-authoritarianism, and anti-imperialism as unavoidable structural preconditions for women's empowerment, children's rights, and social justice (Figure 3).

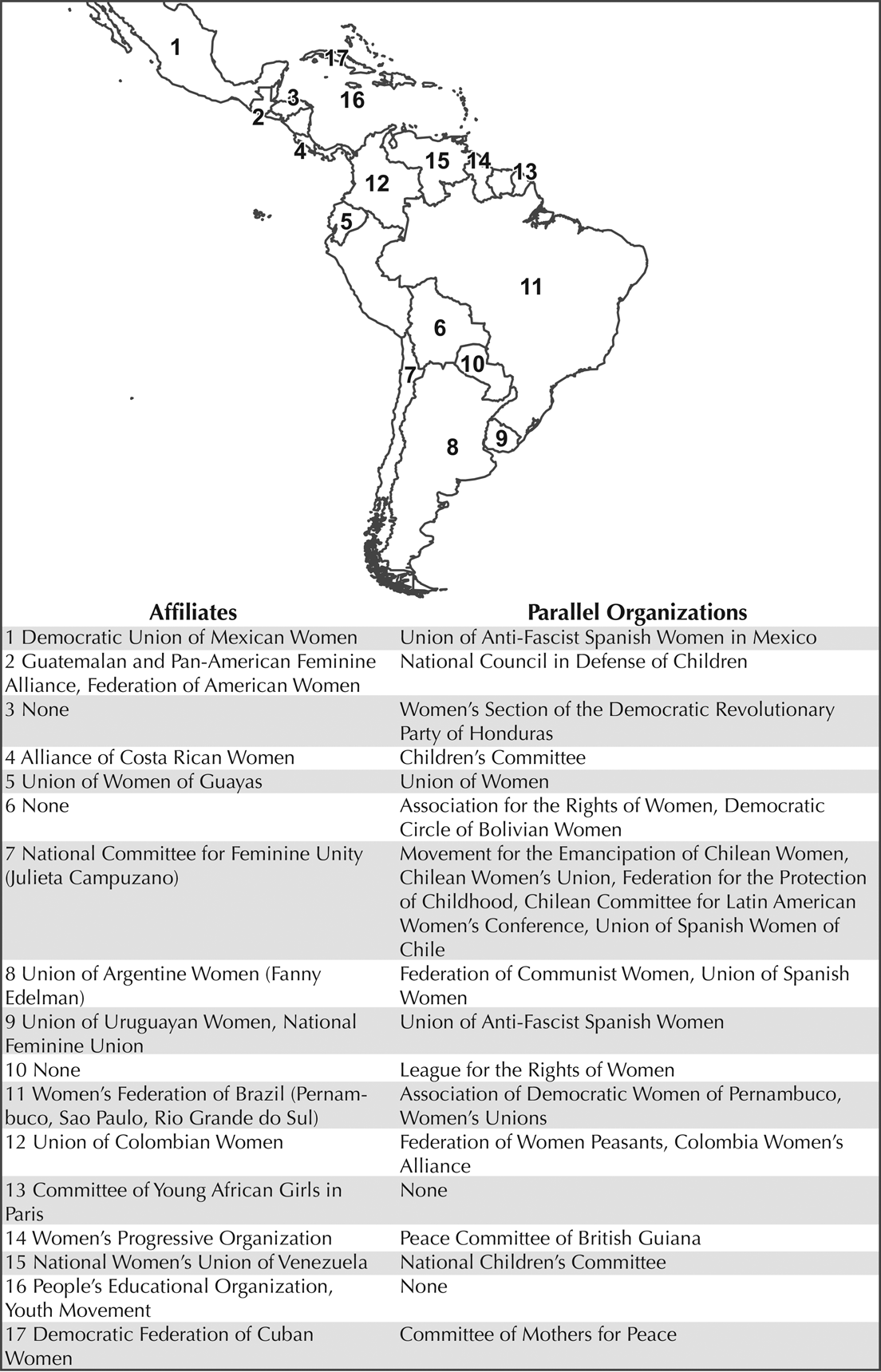

Figure 3. This cartoon was published almost a year after the end of the Korean War (1950-1953). It shows a group of Cuban women marching and carrying banners and flags (some on the left even carry a child in their arms) calling for an international peace agreement and protesting the bacteriological war. In the background we see a typical Cuban countryside with log cabins and palm trees.

FDMC, “Programa de la FDMC”, Mujeres Cubanas, April 1954, pp. 14–17.

In 1952, the military uprising led by Fulgencio Batista against Socarrás's democratic government moved the horizon of war and authoritarianism into Cuba. Several nationalists, reformists, democratists, and left-wing activists spoke up, marched, and fought against the military dictatorship until 1959. The FDMC was one of the few opposition groups exclusively made up of women, together with the radical nationalist Pro Martí Women's Civic Front (Frente Cívico de Mujeres Martianas, FCMM) and the leftist United Oppositionist Women (Mujeres Oposicionistas Unidas, MOU). The FDMC was in the opposition movement, but, as well as the PCC, it is thought that it was not as active as these other women's groups – due to its lack of participation in violent actions and attacks on state institutions. However, as a left-wing group like the PCC, it was monitored by the Political Bureau for the Repression of Communist Activities that was created in 1955. Although the FDMC did not disappear during the insurrection against Batista, its capacity to operate was severely limited, exemplified by the fact that it had to stop publishing its magazine in 1956. It is important to note, however, that FDMC was not demanding the establishment of a communist system once Batista was defeated, but rather the restoration of democracy; in their view, the 1940 Constitution provided a radical enough framework for reforming Cuban society and improving women's political status and living conditions.Footnote 63

Despite the atmosphere on the island, a Cuban representative with no official affiliation, María Antonia González, managed to attend the Fourth International Congress of the WIDF in Vienna.Footnote 64 María González declared that she was speaking on behalf of the clandestine United Oppositionist Women (MOU) group rather than the FDMC. Her speech to the WIDF Congress focused on the repression exercised by the authoritarian regime since 1952. She described how women were used to trap opposition leaders, while others were assaulted, tortured, and raped when suspected of helping the guerrillas and clandestine groups. González also reported that women's organizations such as the MOU – although unable to fight for women's rights due to the extreme political climate – were assisting the imprisoned activists, sometimes with the support of their wives, mothers, sisters, and female relatives. MOU also supported prisoners on hunger strike and lobbied the Cuban High Court to liberate those illegally sent to prison. The conclusions she offered to the WIDF highlighted the significant role women played in every part of the world in the fight for democratic liberties and against the terror.Footnote 65

In summary, the FDMC was more important to the WIDF than traditional historiography has commonly recognized. As Chase discovered, the foundation of the still-extant Federation of Cuban Women (FMC) in August 1960 probably owes more to “old leftist/radical” women (of the FDMC) than to the “new leftist/radical” women (of the “26th of July Revolutionary Movement”, founded by Castro and his colleagues to fight the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista). However, Vilma Espín, a secret participant in the “26th of July Revolutionary Movement” and Raúl Castro's wife, did later become a noteworthy member of the WIDF. Chase argues that the FDMC's ideological foundations – alongside the participation of its members in the First Congress of Latin American Women through the Revolutionary Female Union – marked a turning point in radical women's activism in Cuba a long time before the foundation of the FMC under the revolutionary government.Footnote 66

CONCLUSIONS: SIMILARITIES AND DISPARITIES BETWEEN THE CUBAN AND MEXICAN BRANCHES OF THE WIDF

This article has argued that Latin American women did not just emulate, but also contested and enriched the guidelines issued by the WIDF with demands rooted in their specific material reality. However, several differences between the Cuban and Mexican chapters of the WIDF are worth comparison and further explanations. Both countries are close to the US, and US foreign policy exerted a strong influence on their domestic agendas during the early years of the Cold War. Indeed, both the Cuban and Mexican Communist Party were persecuted and banned. This was due to the influence of the “McCarthyist” victimization of (real and supposed) Marxists in America during the 1950s. The BNMR–UDMM, and the FDMC were, respectively, formed by members of, or ideologically close to, the Cuban Communist Party and the Mexican Communist Party. Likewise, both the Cuban and Mexican WIDF branches were firmly against US imperial policy and its interference in other countries’ national agendas. Both of them had a strong commitment to the development of rural areas and, more specifically, to improving the literacy and access to culture of women peasants.

Neither the BNMR nor the UDMM sought to seriously disrupt gender roles and archetypes, despite their radical ideological backgrounds. Most of their requests concerned women's rights to join representative institutions; they saw maternity and traditional femininity as core ideas. They did not seek to dissolve or challenge the family as the foundational structure of social organization, nor did they seek to overcome the traditional paradigm of women as reproductive beings whose main duty and purpose was to take care of their biological children as a way of looking after the children of the nation. They were less radical feminists than their Cuban colleagues. The Cuban feminists followed traditional female archetypes, and, like the Mexican women, proposed modest new ways to understand femininity and suggested that a woman could have a role within society as an educated worker or peasant, but also as a technician or a liberal arts professional. Nevertheless, the Cuban branch seemed to promote discourses that decolonized, or at least radicalized, traditional concepts of femininity linked to the nation's progress and modernization. In fact, while the FDMC demanded further improvements for Black women, the Mexican groups had made no noticeable mention of Indigenous or Afro-Mexican women by that time. This was linked to the widespread idea, defended by Vasconcelos, that “the mestizo” was the universal race of Mexico. This famous concept attempted to intentionally erase the existence of indigenous people in Mexico. By arguing that all Mexicans were a product of miscegenation between indigenous people and Spaniards, it intimated that there was no need to recognize the existence of a stratified social system that marginalized and excluded people on the basis of race in post-revolutionary Mexico.

Additionally – in line with the communist parties that they were attached to or had close relations with – both women's organizations defended complex discourses about agrarian reform and the need to fight against material deprivation, the lack of vital products, and enable access to vital sources of welfare and happiness such as food, water, health, and education. In this regard, Cuban and Mexican communist women used traditional concepts of maternity as a strategy to mobilize and bring more women into activism. In fact, these organizations developed associations for the Protection of Children as a way of ensuring the safety of all citizens and the future of the nation. Because of this and their shared Marxist ideology, they proposed to build new crèches and day care centres in working class districts. With respect to peasants, they demanded equality between men and women, as well as their rights to be landowners and to have access to water, and they requested the extension of medical services for school-age children.

It would be wrong to depict Latin American feminists as a consistent ontological mirror-image of European socialist feminists. Within the framework of the WIDF, there was no political bloc of socialist or communist feminists united by a Latin American identity or with a common programme for Latin America as a differentiated entity. Nor could it be argued that Latin American communist women worked without hierarchies, free from cultural prejudices. In fact, in a travel story published by FDMC member, Justina Álvarez, after a trip to America, Cuban feminists show a sense of superiority over colleagues from other Latin American countries such as Guatemala, Colombia, Ecuador, or Mexico.Footnote 67 In the same way, another FDMC member, Sarah Pascual, portrays Mexican women as illiterate, powerless, unprotected, and poorer than Cuban ones.Footnote 68

This image contrasts with how Cuban reformist feminists estimated left-wing Mexican women in the 1930s. Prominent Mexican feminist leaders of the FUPDM, such as Refugio García and Adelina Zendejas, were honoured guests at the Third National Congress of Women in Cuba (1939). They spoke about Cárdenas’ revolutionary policies and how Mexican feminists had contributed to enhancing women's living standards and political status.Footnote 69 During the interwar period, Mexico had become the paradigm of revolution in America, while, in contrast, Cuba was embroiled in a period of transition into a constitutional convention in which military warlords, such as Fulgencio Batista, still controlled short-lived civil presidents. However, in the late 1940s, Cuban communist women might well have regarded Mexico as a much less revolutionary country because of the corporative turn of the PRM under Manuel Ávila Camacho, who abolished some of the most radical measures approved by Cárdenas and tried to gain greater control over mass organizations like trade unions, youth associations, and feminist groups.

In spite of these disparities, it is worth noting that the convergence between European and Latin American socialist and communist women within the WIDF strengthened the internationalization of feminism in the twentieth century. This analysis has used personal letters, journals, and the records of international meetings in the early Cold War to show the changing, but increasing, alignment of Mexican and Cuban women to the top-down principles of the WIDF on antimilitarism and women's and children's rights. However, the convergence also sped up the decentralization of that era's feminist paradigm. These meetings and dialogues resulted in a rich exchange of ideas and discussions that also opened the door to grass-roots proposals and demands. Transnational interaction in para-diplomatic circles within the socialist bloc expanded and made more complex the WIDF's political agenda defined in Europe by bringing alternative ideological understandings of women's emancipation together.

To sum up, this article seeks to encourage a reassessment of the role of Latin American left-wing women within the WIDF during the Early Cold War. Although the WIDF created the institutional possibility of an international socialist network of feminist associations in 1945, the success of its development relied not just on the initiatives of its executive committee, council, and secretariat, but even more on the existing logistical structure and disposition of its affiliated national sections. Both Cuban and Mexican communist and socialist women's groups were willing to openly inform the WIDF about their particular problems and challenges, as well as to collaborate in the finance and organization of campaigns launched by other groups associated with the WIDF, such as petitions against military action, authoritarian regimes, or colonial policies in Africa and Asia. As has been argued, the guiding principles of their European colleagues were implemented by Mexican and Cuban socialist and communist women, who always remembered their own national contexts, material conditions, and the historical background of feminist activism. The main programme for women's emancipation within the WIDF could have first been overwhelmingly outlined by European leaders in the mid-1940s. However, this article shows that the increased number of exchanges and contributions made by Latin American left-wing women affiliated with the WIDF during the late 1940s and 1950s paved the way for a true decentralized globalization of women's fights and rights within the Eastern bloc.