Bilibid prison in fact could be likened to a faucet which though used day and night was never without water.Footnote 1

In the days leading to the outbreak of war between the United States and the newly independent Philippine Republic, anticolonial revolutionaries planned a revolt inside Bilibid Prison. In late January 1899, prison physician Manuel Xeres Burgos informed Philippine President Emilio Aguinaldo, “it is absolutely necessary that an order be received here permitting the uprising of those in prison before the movement is begun anywhere else”.Footnote 2 Jacinto Limjap, imprisoned for financing the revolution against the Spanish colonizers, drew up the plan for arming prisoners with rifles taken from the US Army barracks opposite the prison. As commander of the volunteers inside the penitentiary, he coordinated with Aguinaldo’s General, Teodoro Sandiko, on the outside.Footnote 3 Aguinaldo and Sandiko stationed 600 troops, called sandatahan, on the outskirts of Manila in preparation. US officials, who had intercepted their communications, feared a simultaneous attack from inside and outside the city before reinforcements could arrive.Footnote 4 On 4 February 1899, US troops fired on a sandatahan patrol on the edge of Manila; they returned fire, and the exchange marked the start of war. The ensuing US attack left 500 Filipinos dead and pushed Aguinaldo’s forces out of Manila.

During the war, the US military captured scores of revolutionary leaders and nationalist political writers. Those who refused to swear a loyalty oath to the US, such as Apolinario Mabini, Artemio Ricarte, Maximo Hizon, Pio del Pilar, and Pablo Ocampo, were exiled to Guam.Footnote 5 In so doing, US officials were clearly following the precedent set by the Spanish system of deporting political prisoners to far-flung islands, such as Guam and the Marianas Islands.Footnote 6 Yet, while US colonial officials exiled better-known figures, they also sought to reclassify significant portions of the ongoing anticolonial struggle as bandits, rather than members of lesser-known and long-misunderstood movements led by those who refused to assimilate into either US colonial, or Filipino nationalist regimes.Footnote 7

Continually afraid that revolts would trigger widespread uprising, US officials used transportation within the archipelago to dissipate revolutionary pressure. In this way, penal transportation came to be used not as a commuted sentence, as an alternative to death or life imprisonment, as it had been in British, French, and Iberian empires. Rather, it was designed to work in concert with incarceration. This, too, was not wholly without precedent. Indeed, Spanish officials had used intra-colonial transportation within the Philippine archipelago to try and incorporate non-Christian regions, such as Mindanao and Palawan, and thereby expand their political and territorial jurisdiction.Footnote 8 Thus, according to historian Greg Bankoff, Spanish colonial governors used a “policy of enforced migration under the guise of penal deportation” to send “undesirable” Christian Filipinos to coastal sections of Mindanao and Palawan.Footnote 9 Strikingly, when US officials took control of the prison system in the Philippines at the dawn of the twentieth century, they used transportation for the purposes of counterinsurgency and racial management under the guise of prison labor transfers. In fact, in some instances, they intentionally reversed the flows by using non-Christian Moros from Mindanao as prison guards to oversee Filipino prisoner labor.

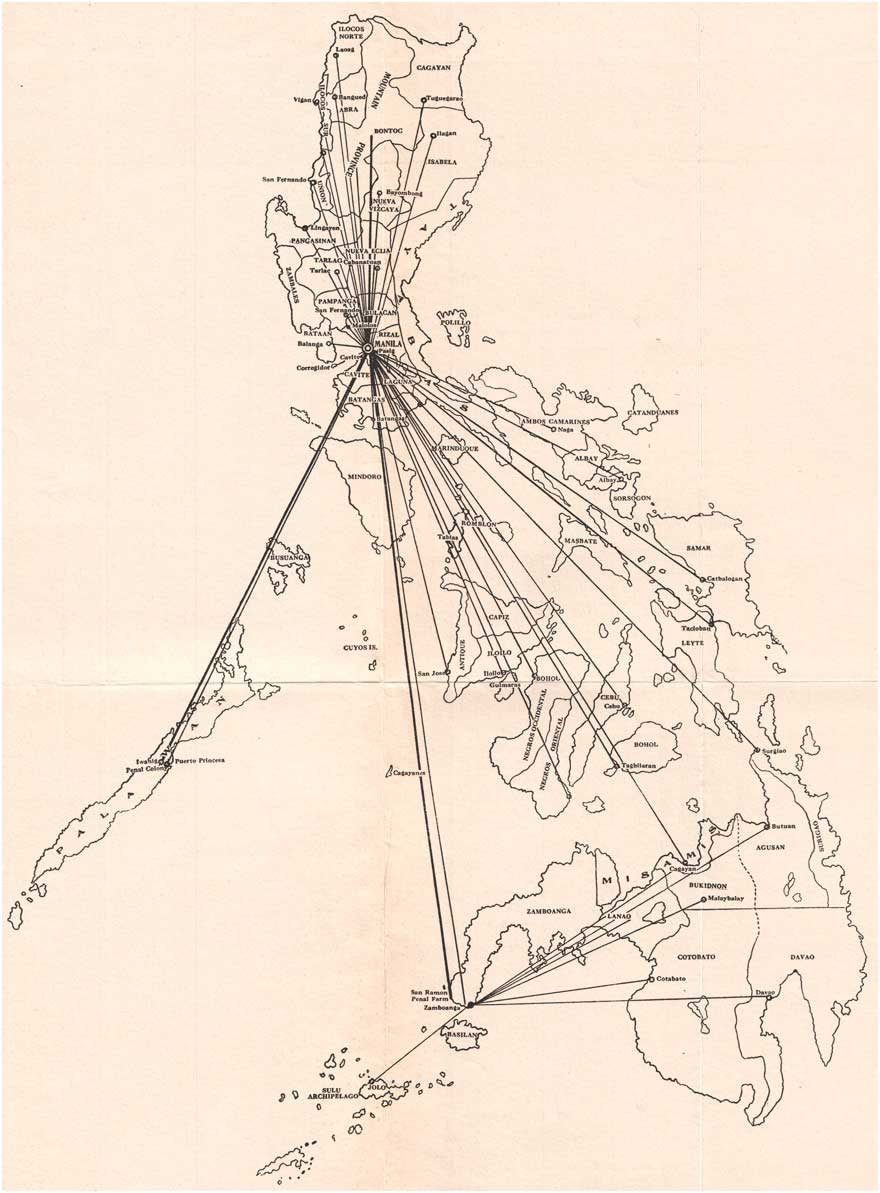

Bilibid Prison was the hub of the network of prisons US colonial officials inherited from the Spanish. Under US colonial rule, that network included the San Ramon Penal Farm in Mindanao, the Iwahig Penal Colony on the Island of Palawan, Bontoc Prison in the Mountain Providence of Northern Luzon, Fort Mills on Corregidor Island, and a host of provincial jails, temporary facilities, and detention sites listed in colonial reports merely as “other stations”. Historians have generally characterized these prisons as “colonial laboratories” for experiments in racial classification, benevolent assimilation, and work discipline, and for good reason.Footnote 10 Yet, just as this essay is concerned more with the forcible transport of populist leaders, rather than the deportation and exile of well-known political prisoners, it likewise focuses on these prisons as nodes in an intra-colonial transport system, rather than on the social history of life inside the prison itself.

Looking behind the official rationale of transporting prisoners merely to use their labor on public works, it becomes clear that transportation and incarceration were conjoined strategies of carceral colonialism driven by the constant fear that prison revolt would trigger a flood of wider uprisings. For anticolonial fighters, on the other hand, prison revolt catalyzed opposition to US occupation, and escape from forced transport became a powerful act of resistance. For both sides, the revolutionary impulse was carried forward in the metaphor of the flood. Thus, by re-examining the connected histories of revolt and transportation as counterinsurgency from the perspective of the colony, this article also shows how experiences of incarceration shaped anticolonial leaders’ freedom dreams and practices.

Figure 1 The US Colonial Prison System in the Philippines.

FEARING THE FLOOD: TERRAINS OF COUNTERINSURGENCY

The Bilibid revolt was a cornerstone of US justifications for war. When explaining the outbreak of hostilities to the US War Department back in Washington, DC, for instance, Major John R. Taylor put the prison plot at the heart of a coordinated uprising in Manila that would have slaughtered every American in sight. It was not difficult for Jacinto Limjap to find volunteers to “rob, to burn, to rape, and to murder”, Taylor claimed, because that was why they were sent to prison in the first place. He argued that, as the uprising spread from Bilibid across Manila, servants would rise up and kill their masters, insurgents disguised as civilians would attack US Army barracks, and white people would be massacred in the streets. “If the plan had been carried out”, Taylor reported, “no white man and no white woman would have escaped”.Footnote 11 For officials like Taylor, the narrative that dangerous prison revolt would lead to widespread anticolonial uprising figured prominently in what historian Ranajit Guha elsewhere called the “prose of counterinsurgency”; that is, the need to characterize subaltern insurrection as irrationally violent to justify colonial law and order.Footnote 12

Other US officials, like Dean Worcester, who had just been appointed to the First Philippine Commission by US President William McKinley, relied heavily on Taylor’s narrative to assert that the Filipinos had brought war upon themselves.Footnote 13 In contrast to political claims of sovereignty, like the “Malolos Constitution”, the specter of prison revolt was repeatedly pointed to as the prime example of how Filipinos were treacherous, irrational, uncontrollably violent, and hence unfit for self-rule. According to Worcester, it was prison revolt igniting mass urban uprising that proved Filipinos were motivated only by malicious “savagery”, rather than “any fixed determination on their part to push for independence”.Footnote 14 From the inception, as accounts like Taylor’s and Worcester’s illustrate, prison revolt lay at the core of white-supremacist fantasies of race war in the Philippines.

The US counterinsurgency campaign relied on the production of geographic and ethnographic knowledge as well as boots on the ground. Frustrated by ongoing guerrilla warfare, military officials sought to map the unfamiliar terrain. Initially, they used existing Spanish atlases, borrowing heavily from their cartographic lexicon and colonial imaginary. Once they began creating their own survey maps, the War Department overlaid another set of categories of regional difference. Along with the census, US colonial officials conducted population studies, including anthropometric measurements of prisoners inside Bilibid. Together, these technologies of governance produced a powerful and lasting set of ideas about religious, racial, and regional difference that were mapped onto explanations of criminality over the first decade of US occupation.

The War Department’s first survey map of the archipelago reveals how overlapping Spanish and US imperial regimes produced forms of carceral innovation in their attempt to control rebellious terrain. According to Henry S. Pritchett, the Superintendent of the US Coast and Geodetic Survey Office, the Philippine Commission had commandeered a series of maps being made by the Jesuit Observatory in Manila in 1899. This atlas, he informed President William McKinley, “fairly represents the present state of geographic knowledge of the Philippine Archipelago”.Footnote 15 The Mapa Ethnographico, as it was called, symbolized some sixty-nine different ethnic groups, lumped into three racial types, and plotted onto discrete areas of land: territorio de los cristianos hispano-filipinos, territorio de los cristianos nuevos y los infieles, and territorio de los moros. The War Department’s first survey map kept the Spanish tripartite division of the same archipelago into degrees of religious conversion, even retaining the same color to represent the Moro, predominantly Muslim, provinces in the South. It also split the archipelago into North and South, shading some areas as controlled by “civil provincial government” and others as controlled by “Moro and other non-Christian tribes”.Footnote 16

At the same time, census takers under the direction of the Philippine Commission surveyed the islands’ peoples. The Census of the Philippine Islands presented a series of carefully staged photographs of people from various islands arranged along a gradient of supposed “civilization”.Footnote 17 The census proved to be a devastating tool of imperial governance, with far-reaching social consequences for the construction of criminality. Other forms of ethnographic knowledge were produced by officials like Dean C. Worcester and anthropologists like Daniel Folkmar, whose Album of Philippine Types set out to classify the inmates of Bilibid Prison. The operative spatial category for these men was a static North–South binary and Folkmar sought to sort his subjects into northern (whom he considered generally “tall and long-headed”) and southern (“short and broad-headed”) types.Footnote 18 His theories rested on broader anthropological and social-scientific ideas of the day, particularly the belief in physiognomy and phrenology, that the outer surface of the head bore signs of inner character. What is especially striking is the eerie parallel between imagining the topography of the skull, with its presumed regions of localized mental faculties, and the topography of the land, with presumed regions of localized deviance.Footnote 19

The conflation of theories about geography with natural history, climatology, and racial science was central to the emergent fields of criminology and penology at the dawn of the twentieth century. The Attorney General’s massive multi-volume study, Criminality in the Philippine Islands, sought to compile crime statistics in order to advance regionalized explanations for what he came to call the “propensity to crime”.Footnote 20 He was especially preoccupied with the “influence of local conditions on crime”, and sought to show how “aggressive tendencies” produced crimes against persons (parricide, murder, homicide, physical injuries), “nutritive tendencies” caused crimes against property (robbery, theft, embezzlement), and “genesial tendencies” resulted in crimes against public morals (adultery, rape, abduction, seduction, corruption of minors). These tendencies, moreover, became mapped onto an imagined geography that artificially cut the archipelago into three distinct regions, identified in terms of the prevalence of certain types of criminality. This new tripartite regional division formed a hybrid of older Spanish geographies of religious classification and the rigid American North–South geography of racial simplification and hierarchy. These areas were chosen, he insisted, because of the “ethnological and geographic affinity between the inhabitants”.Footnote 21 Mapping and the census as technologies of rule were combined with the rise of criminal statistics to produce a carceral geography that regionalized supposed deviance and targeted alleged perpetrators.

This kind of geographic knowledge, like the Attorney General’s collection of regionalized crime statistics over the first ten years of US colonial rule, constructed a cartographic imaginary that fused criminality to discrete territories. According to this explanatory scheme, Mindanao and the islands of the southern archipelago were seen to be overly aggressive and insurrectionary, the islands of central and southern Luzon symbolized the moral degeneracy associated with rapidly growing urban centers like Manila, and the far north was seen as dangerously poor, hungry, and in need of improvement. Genesial crimes in the cities, reasoned the Attorney General, were surely the result of “the loosening, if not breaking up, of religious beliefs, which leads to the relaxation of customs”.Footnote 22 Ultimately, differently classified peoples – civilian, subject, criminal, insurgent – were seen to necessitate distinct modalities of rule, authorizing drastically different scales of violence.

The early reports of the Secretary of Commerce and Police reveal how this kind of thinking about regionalized criminality informed counterinsurgency strategy. Writing in 1903, for example, Secretary Luke E. Wright described the fear that ladrones and gangs of robbers would swoop down and prey on the rest of the population before taking refuge again in the “mountain fastnesses”.Footnote 23 Formidable bands of “considerable magnitude” had sprung up in the provinces of Rizal, Cavite, Albay, Iloilo, Cebu, Suriago, and Misamis according to Wright. Their leaders managed to evade capture by concealing themselves in the remote mountains.Footnote 24 In this paranoid environment, officials blurred the lines between pre-emption and retribution, killing and incarceration. As Wright put it: “the speedy killing and arrest and punishment […] of outlaws has already produced a most beneficial effect and has borne in on the minds of those likely to depart from the path of peace in future”.Footnote 25

BEING THE FLOOD: ANTICOLONIAL FREEDOM DREAMS AND PRACTICES

Given this context of mass criminalization, escape and prison revolt became two central currents running through revolutionary struggles against US occupation. Social historians of popular independence movements in the Philippines have long warned against subsuming their various aims into a singular elite-nationalist narrative of seeking political rights in the nation state. By focusing on the meaning of revolution to the masses, for instance, Reynaldo C. Ileto focuses instead on the vitality of the messianic and millennial visions within these movements.Footnote 26 He shows how revolutionary ideas that surfaced in poetry and political street theater were channeled into a “revolutionary style” by brotherhoods like the katipunan, and erupted in people’s uprisings against Spanish and US rule. Vicente Rafael meanwhile suggests that these revolutionary movements opened a new experience of sovereignty, based in kayalaan, understood as “freedom from the necessity of labor and the violence of law”, in contrast to US and elite-nationalist doctrines of sovereignty claims.Footnote 27 Following this line of argument, prison revolt in the Philippines can be seen not only as an affront to US sovereignty claims, but as an alternative practice of radical freedom itself.

Breaking out of prison as an act of individual liberation leading to collective salvation was a recurrent theme throughout the various waves of revolutionary activity in the Philippines. Consider the case of Felipe Salvador in 1902. That year, US officials tried to propagate the fiction that war had ended by declaring a handover from military to civil government. Governor General William Taft led the Philippine Commission in passing legislation to try and render abstract sovereignty into actual jurisdiction on the ground. The Sedition and Bandolerismo laws of 1902 provided the legal architecture for hunting down and locking up all remaining “insurgents”, suddenly reclassified as outlaws and bandits rather than anticolonial freedom fighters.Footnote 28 Felipe Salvador was legendary. He had defeated 3,000 Spanish with an army of 300 at the battle of San Luis in Pampanga in 1896, captured 100 Mauser rifles from the Spanish, and led a triumphant march through Candaba after Pampanga had been liberated from the Spanish in 1898.Footnote 29 He had amassed an enormous following, causing him to be routinely tracked by US intelligence forces. Ensnared by the new laws, he was captured in Nueva Ecija on charges of sedition and transported to Bilibid Prison in 1902. But when they passed Cabiao en route, he escaped.

To his followers, Salvador’s escape was seen as an individual act toward communal freedom. He had predicted it, telling his followers he went to jail voluntarily and would walk free when he chose.Footnote 30 It was also one among a series of prophecies featuring imprisoned leaders as harbingers of liberation that had deep roots in the original katipunan. During the war against the Spanish, Salvador promised the return of revolutionary hero Gabino Cortes along with seven archangels to shield them from the bullets.Footnote 31 In preparation for war against the Spanish, Andrés Bonificio and other katipunan leaders had ascended Mount Tapusi to write “long live Philippine independence” in chalk on the wall of the Cave of Bernardo Caprio. King Bernardo, “hero of the Indios”, was said to be “imprisoned in the cave, awaiting the day when he would break loose and return to free his people”.Footnote 32 During Felipe Salvador’s escape, he too ascended a mountain top. After wandering in the nearby forests and swamps, Salvador climbed Mount Arayat and returned with a prophecy: “a great flood would wash away nonbelievers and precipitate the impending battle for independence”.Footnote 33

The years following the US transfer from military to colonial government in 1902 were marked by what the Philippine Constabulary referred to as the period of “papal resistance”.Footnote 34 These militant religio-political movements were led by messianic figures like Felipe Salvador, called “Popes”, and traced their origins to the katipunan. According to the Constabulary, in addition to Salvador’s Santa Iglesia, other resistance organizations included the Tulisans, Dios-Dios, Colorados, Cruz-Cruz, Cazadoes, Colorums, Santo Niños, Guardia de Honor, Hermanos del Tercio Orden, and Babaylane.Footnote 35 Vic Hurley, honorary Third Lieutenant and chronicler of the Philippine Constabulary, carefully recorded the messages and movements of these Popes. He also uncovered visions of freedom defined in opposition to imperial notions of law and order.

Describing the Tulisan movement led by Ruperto Rio, self-proclaimed “Son of God” and “Deliverer of the Philippines”, Hurley focused on the meaning of independence to the organization. While being interrogated, a wounded Tulisan prisoner spoke about a box inscribed with the term independencia; it was in the box, he told his captors, but had now flown away back to the Pope to be enclosed again in a new box. “The fanatic rolled his glistening eyes as he drank in the thought of the approach of the millennium”, wrote Hurley. “When independence flies from the box, there will be no labor, señor, and no jails and no taxes […] and no more constabulario”, explained the prisoner.Footnote 36 Here was an understanding of freedom predicated on the abolition of policing, prisons, taxation, and labor. Messianic leaders like Ruperto Rios and Felipe Salvador were promising total revolution in the Philippines, social transformation rooted in reversing the collective experience of criminalization.

The revolutionary impulse carried forward the metaphor of the flood. Two years after Felipe Salvador’s escape en route to Bilibid, for example, the Philippine Commission intercepted a call to arms. Writing to Dionisio Velasquez and all members of the Santa Iglesia, estimated to be 50,000 strong, Salvador asked them to assemble the brothers of the katipunan and ready the soldiers: “I therefore request that you do all you can in order that we may have our self-government within the month of October”.Footnote 37 The Constabulary believed he was using the old Spanish Weather Bureau’s infrastructure to circulate predictions of floods.Footnote 38 The Detective Bureau believed Manila to be continually in danger. “This city has always been the storm center of these political typhoons, and the least variance of sentiment or feeling of unrest is at once noted”, wrote Secret Service Chief C.R. Trowbridge.Footnote 39 Although Salvador’s plan for an uprising did not come to pass in 1904, revolutionary forces continued to muster and would again break loose in the “People’s Rising” of 1910. By that time, it was clear that it was not only Salvador’s followers who believed the prophecy of the great flood, but US colonial officials were also thinking about revolutionary currents in terms of fluid dynamics. If Manila was the storm center, Bilibid would again be its epicenter.

Figure 2 Bureau of Prisons Map with Bilibid at the Center. Bureau of Prisons, Catalogue of Products.

CRIMINAL TRANSPORTATION AS VALVES OF REVOLUTIONARY PRESSURE

As US officials consolidated geographic and ethnologic knowledge to produce cartographies of criminality, they increasingly relied on incarceration and convict transportation in their counterinsurgency strategy. First, they exiled political prisoners to Guam. Then, over the first decade of US rule, they built a network of prisons around the archipelago and moved prisoners to different locations in order to separate them from regional affiliations and bases of support. As they developed more elaborate transport systems, officials began strategically creating and exploiting regional antagonisms as a way of managing convict labor. Justified as labor transfers, it was clear that US officials were seeking to rationalize counterinsurgent racialization through the mechanism of capitalism.

Police and Commerce Secretary W. Cameron Forbes became obsessed with transportation and prison administration as twin hallmarks of governance. Read alongside police and prison reports, Forbes’ personal journal reveals the extent to which he saw himself as a mastermind of convict transportation in the Philippines.Footnote 40 Beginning with the establishment of the Iuhit penal colony on Palawan Island, later renamed Iwahig, Forbes began using Bilibid as a valve, redistributing revolutionary pressure around the islands. Officially, the colonial government used convict transportation to relieve the overcrowding at Bilibid that they blamed for the unsanitary conditions and rampant disease that periodically killed hundreds of prisoners.

Tracing the plans for prisoner transportation through Forbes’ journal also shows how he imagined it as a way of fixing the “labor problem” and building the requisite infrastructure to maximize economic penetration of regions he deemed unproductive or underproductive. In the fall of 1904, for instance, he had promised to send 1,000 prisoners to General Wood to build roads in Mindanao and another 500 to General Allen in Albay for work on the Tabaco-Ligao road.Footnote 41 The next year, General Wood requested an additional 250 prisoners to work on his railroad from Overton to Marahui in Mindanao, and the 1,000 prisoners used to complete the Tabaco-Ligao road were moved to Jovellar to begin work on the Guinobatan project.Footnote 42

In moving these prisoners around, Forbes sought to destroy local ties, exploit regional antagonisms, and design new systems of racial management.Footnote 43 Describing the road-building project in Mindanao, for example, he gloated that he was able to save the Insular treasury the money to guard them: General Wood “has an easy time guarding them as the Moros hate the Filipinos and will be standing along the dead line hopping from one foot to the other waiting for an opportunity to kill any prisoner that steps over”.Footnote 44 Or, in Albay, when forty-two starving prisoners fled the road-building camp, Forbes reported that they enlisted the help of eager “natives” in hunting them down.Footnote 45 Similarly, when thirty-six prisoners escaped by boat from a work detail on Malahi Island, “natives” in the province “showed very active interest” in recapturing them “dead or alive”. The escape launch, which soldiers had fired on from the shore, was recovered “drenched with blood”.Footnote 46

Regional differences were racialized in the minds of colonial officials, and they sought to create civilizational hierarchies that could be used to manage various degrees of unfree labor. The Benguet road-building project was especially illustrative of this. Begun in 1901, engineers had made only halting progress in pushing forward earlier Spanish attempts to make the Benguet highlands “accessible to the white man”.Footnote 47 After Taft and the Philippine Commission declared their intention of making Bagio their summer capital, they brought in Major L.W.V. Kennon to take over construction. He experimented with convict labor when 200 prisoners were sent from Bilibid to Twin Peaks that year, but reported less than promising results. Disease had ravaged them, many died, others escaped, leaving the rest so “demoralized” that they were “useless as laborers”.Footnote 48 Another problem according to Major Kennon was that working them near road-building Camp 3, above the 900-foot sheer drop called “Devil’s Slide”, meant that they could not be shackled while working without risk that they might fall off the cliff.

The larger population of unshackled workers were also racialized and criminalized in Kennon’s view, and the two were co-constitutive. American Camp foremen had been given police powers, he wrote, and “considering the class of workers there – Japanese, Chinese, Filipinos, Igorrotes [sic], and Americans including negroes – it is surprising to me that there is so little crime”.Footnote 49 Quoting his predecessor’s view of their supposed racial capacities to labor, he reflected on the idea that Filipinos only worked under the direct charge of a white foreman: “they quit or go idle the minute the eye of the white man is off them”. The inclination to “lay off”, he continued, was common to the Filipino and the “American negro”.Footnote 50 These road engineers had figured that the Filipino was equal to about one-fifth the amount of work of a “good white laborer”, while the “Igorrote was a ‘vastly superior animal’ and equaled ‘three Ilocanos or Pangasinans in wage value’”. Working parties of “different tribes”, Kennon concluded, “were sometimes pitted against each other and a spirit of emulation was fostered which increased the output of their labor”. The rivalry between Tagalogs and Ilocanos, for instance, created competition over who was considered a better workman.Footnote 51 Even though convict labor may not have been as efficient for road work in this case, convict transportation enabled officials to pit groups against each other, and the strategic insertion of the criminalized subject as negative referent for the relative degrees of freedom enjoyed by the other groups of workers was used to powerful symbolic effect.

Men like W. Cameron Forbes, Leonard Wood, and L.W.V. Kennon moved people around and forced them to work as a counterinsurgency strategy and considered it a defining feature of imperial sovereignty. Indeed, Bilibid’s first warden, George N. Wolfe, imagined a revolt of some 200 detention prisoners to be caused by “lack of work”.Footnote 52 When authorities captured the “inciter of a riot in Samar”, Forbes suggested work as the proper cure for such rebelliousness, that he be given “good employment in Bilibid”.Footnote 53 Contrary to the pronouncements of visiting officials like President McKinley’s physician, Mr Rixey, who remarked that it was “a pity the whole population shouldn’t serve a term in Bilibid to be built up physically and made useful laborers”, the archival record is riddled with evidence that prisoners were starved when incapacitated and fed more when put to hard labor.Footnote 54 In 1904, the quantity and cost of rations for “native and Asiatic” prisoners inside Bilibid, for example, was valued at 0.16 of a Philippine peso, while the rations for “European and American” prisoners were more than double, 0.39. The average cost per ration for prisoners working on roads in Albay Province meanwhile was 0.28.Footnote 55 Evidently, prison administrators sought disproportionately to press downward on the social reproduction of those held in captivity.

Racial categories not only affected the quantity and cost of rations inside Bilibid, but also the type. That same year, an Executive Order had to be passed prohibiting the use of “polished rice” in government institutions due to “the relationship between a diet too largely composed of such rice and the prevalence of beriberi”.Footnote 56 Here, in these reports, then, are traces not only of how racialized criminal subjects were fashioned discursively, but also how they were quite literally being made materially. Sovereign power in the prison system came to be understood not only as the monopoly on deadly violence, but as managing human life down to minute calculations of cost and caloric intake.

By the time W. Cameron Forbes took over as Governor General, he had developed a full-fledged theory of sovereign power based in his experience administering policing and prisons. It was apparent in the systems he designed for controlling the mobility of certain targeted groups, for commanding the labor of racialized criminal subjects, and for managing social and biological reproduction. Yet, it was perhaps most clearly showcased in his rationale for how he used the pardon power. Unlike the American system, “under the Spanish system the Governor General was viceroy with all the powers of the king and as such could pardon anywhere”, Forbes wrote in his journal. “The Filipinos liked to have their Governor General full-powered and I took these actions without any question as to my power and without any questions raised by anyone else”.Footnote 57 Likening himself to a benevolent monarch, Forbes’ vision of imperial power was infused with the white-supremacist and misogynist notions of having complete discretion over those he considered beneath him.

Patriarchal self-fashioning underpinned Forbes’ gendered ideology of imperial sovereignty. He took pride in being able to judge a “nice girl” from a “quarrelsome hussy”, or a “very dainty pretty little Filipina” from “undesirable women of the lower class”, and to use his discretionary power selectively to pardon them.Footnote 58 He grabbed every chance to “ridicule men with long thumbnails”, what he considered an unmanly “oriental sign of degradation” proving that they “belong to a class who does not have to work”. As they “can’t be of any use” to their people, Forbes wrote, “they might as well stay in jail”.Footnote 59 His gendered theories cut both ways: being the wrong-looking sort of man, therefore, was reason enough for him to keep someone imprisoned rather than pardon him.

True manliness, on the other hand, was reserved only for white men according to Forbes. The creation of a penal colony was central to Forbes’ convict transportation plans from the outset. He also saw it as a proving ground for his theories of manliness as management. Forbes blamed the initial failures that beset the plan to establish the penal colony on Palawan Island on a lack of strong leadership; “the success of an experiment depends on the executive capacity of its chief”, he wrote.Footnote 60

In 1905, a prison revolt of over one hundred prisoners led by Simeon Mamañgon, Bastonero Mayor, Regino Ibora, and “Moro Macalintal” led to the capture of penal colony Superintendent Dr. J.W. Madara and enabled thirty-three to escape.Footnote 61 After the escapees were hunted down, captured, or killed, Forbes chose Col. John R. White, a “manly chap”, to take over and reform the penal colony. Despite its reputation for disease and violence, Forbes imagined this to be the opportunity of a lifetime: “Think of the chance for a young man, two thousand laborers absolutely at his call, twenty-two thousand acres and a virgin tropical soil […] the world his.”Footnote 62 He promised to back Col. White in his efforts to strengthen his authority, but White confidently informed him that “they would find out quick enough who was master”.Footnote 63 Given the colony’s chaotic start, Forbes worried that other officials like the director of public instruction might try and “emasculate” his scheme by blocking his proposal to create a hierarchy among prisoners based on heteronormative tropes of masculinity having a wife, children, and serving as an inmate-guard.Footnote 64

According to his plan, male prisoners sent to the penal colony would be given women as a form of incentive or reward. Indeed, the list of necessities Forbes requested for Iwahig included “cattle, machinery, wives of settlers”.Footnote 65 In a letter to Forbes, the new penal colony superintendent John R. White wrote that the women he had found “prostituting” when he arrived were “allotted to the prisoners” with very satisfactory results. Given an apparent shortage of women in the colony, White also requested authority to send ex-prisoner foremen to the provinces to “collect families of prisoners and conduct them to Iwahig”.Footnote 66 This was in accordance with Forbes’ “General Plan for Iwahig”, in which he had countenanced that “the only way of having the prisoners contented and the project a successful one is to have a fair percentage – at least thirty per cent – supplied with families”.Footnote 67 Yet, Forbes also cautioned that women not be sent to the prisoners as soon as they arrived at the penal colony, but rather be used as an incentive for good behavior. In his instructions to White, Forbes recommended that women be “rigidly excluded” from the “Barrack Zone” of the penal colony, and that only married women be allowed in the “Home Zone” and “Free Zone”. While he recommended that the government pay to transport women who wished to marry the prisoners, the system of queridas, or sweethearts, would not be tolerated. According to this scheme, men in the Barrack Zone would be allowed only occasionally to glimpse the presence of married women in the other zones and were explicitly prevented from having contact with women right away: “a prison is a prison and criminals are criminals until by good conduct extending over a period of sufficient time they have demonstrated their capacity to be citizens. For this reason it is deemed inadvisable that prisoners should be allowed to have their women and have their children during the probationary period”.Footnote 68 Forbes concluded in his letter to John White: “I am convinced that with the labor at his disposal, the penalties he can inflict, and the inducements he can offer that he can practically dictate the action and conditions of the residents of the settlement”.Footnote 69 Here, treating women as provisions to incentivize prisoners was considered necessary to produce a certain kind of political subject; one who would direct his energy into family rather than insurgency.

CONCLUSION

Prison revolt in the Philippines served as a lightning rod for wider anti-colonial struggles against US occupation. At the end of Spanish rule, Bilibid Prison was characterized as a faucet with an unending supply of criminalized subjects flowing through it. Over the first decade of US rule, it became used as a valve for distributing revolutionary pressure around the archipelago. Mass criminalization was central to the imperialist logic, which maintained that Filipino subjects were unfit for freedom or self-rule. Through convict transportation, US officials sought to remove particular threats from their support bases, to cut off and isolate revolutionary leaders from their networks of belonging. Through mass criminalization, officials also exploited imagined cartographies of regional difference, rendering them into elaborate plans for race management. These transportation schemes relied on a theory of monarchial sovereignty as absolute power, not just to decide on the exception or hold the monopoly on violence, but to manage life by forcibly moving people around and compelling them to work. This vision of sovereignty, at once imperial, patriarchal, and white supremacist in its attempt to control all facets of social and biological reproduction, was most clearly evident in the administration of the colonial prison system.

Felipe Salvador’s prophecy of a flood leading to independence can be seen in the waves of anticolonial revolutionary movement against this version of US sovereignty. First, there was the recurrent theme that imprisoned leaders – Bernardo Carpio, Andrés Bonificio, Gabriel Cortes – would return as harbingers of liberation. Next, was the growing sympathy for fugitives from law-and-order “justice” – Felipe Salvador and Julian Montalon – rooted in the collective experience of criminalization under US colonialism. Prison revolts – by Jacinto Limjap, Juan Leandro Villariño, and Arturo Baldello – were seen as triggers of widespread uprising. And, the revolution – whether Salvadorist or Aglipayan – was said to wash away established hierarchies of wealth and power.

Those alternate ideas and practices of freedom were shaped by experiences with incarceration. If, as Vicente Rafael suggests, the Philippine revolution opened a more “miraculous” experience of sovereignty as the “evanescent opening of an entirely new life”, prison revolt symbolized a radical break from one condition and entrance into another state of being.Footnote 70 As symbol of anticolonial revolution, it unworked the mechanism by which freedom fighters had been transformed into “outlaws”; through revolt, the imprisoned would be turned back into revolutionary leaders, thereby reversing the imperial process of criminalization.Footnote 71 Perhaps this is what the unnamed Tulisan prisoner was pointing to in his definition of independencia as the abolition of police, prisons, taxes, and labor.