THE “CALL” AND THE CALLING

It was such a dilemma! Our everyday life in a little flat, the jasmine sapling in our balcony, the night-queen bush at the corner of our tiny garden, the chilly plant had just started blooming, my four-year old Smita's petite hands around my shoulder and above all my own city, friends, my country. But the call was from dreamland Europe – the beauty, history, famous museums, architecture of Paris, Rome, snow-capped Alps and the dark greenery of Black Forest, rippling waves of the Mediterranean and the modern shining cities of Germany.

And finally, it was a call from the socialist world, a world of which I, and many like me, have dreamt. It was a call not only to visit, but to live there for a couple of years – it was, in the truest sense of the term, an invitation to experience the land of socialist dream. I could see in front of me the legion of socialist women leaders – Valentina Teseshkova, Dolores Ibaruri, Madam Fucikova, Angela Davis, Vilma Espin Castro, Bussy Allende, Freda Brown, Madam Nguyen, Isam Abdulhadi – jewels of socialist women's movement! It was a chance to meet them, to work with them. How could I refuse it!Footnote 1

Malobika Chattopadhyay experienced these conflicting emotions in 1984, in her hometown of Calcutta, after receiving an invitation to work as the Secretary of the Asian Commission at the headquarters of the Women's International Democratic Federation (WIDF) in East Berlin.Footnote 2 Chattopadhyay was a member of Pashchim Banga Mahila Samiti, the provincial wing of the socialist women's organization associated with the National Federation of Indian Women. Her name was put forward by the leadership of her organization for the official position of Asian Secretary in East Berlin. The two quoted paragraphs are excerpted from her travelogue Biswaloker Ahvane (hereafter, BA),Footnote 3 which she compiled as a book from her diaries and scattered memoirs in Bengali literary magazines nearly twenty-five years after her three-year stay in East Germany (1984–1987). Chattopadhyay's book is remarkable for many reasons, and the aim of this article is to explore her text through the nuanced meanings it offers in terms of both the interiority of Indian women socialists and Indian women's participation in international socialist women's organizations. It testifies to the dreams that Indian socialists held concerning European socialism. As a woman, as a socialist, and as an Indian socialist woman, Chattopadhyay explains the subtle ways in which those dreams confronted the realities of living in a European socialist society. She describes in detail the city she inhabited for three years, the countries she visited as part of her job, her colleagues from different corners of the world, and the nature of her work. The book also provides glimpses of her inner world as a traveller in a country that was far from her home, in so many ways. The emotions she struggled with while living on her own for the first time in her life, while in her forties, and the critique she gradually developed of the collective dream she had shared with her comrades at home constitute an inner world of self-realization. By the end of her text, Chattopadhyay hints at the crystallization of a resolution that realities may fail to match the promises of a socialist society, but the dream must carry on. The four sections of this article explore the interwoven details of interiority and public everyday life in her book.

BA has not yet featured prominently in the pantheon of Indian women's writing, perhaps because attention has so far not been paid to the creative and experiential worlds of women who were members of leftist political parties or literary and cultural organizations in India.Footnote 4 The first task of this article is to situate this travelogue/memoir in the context of women's involvement in socialist politics in India, especially in Bengal, and explain how Malobika Chattopadhyay emerges as a significant voice in charting the rich but hitherto ignored history of Indian socialist feminists’ organizational interaction with WIDF in the context of international socialist feminism.Footnote 5 It is equally important to locate this memoir in the cultural history of Bengali women's travel writing. Since the 1870s, this had included a range of experiential narratives, initially travel from the colony to the metropole, and later from postcolonial locations to European metropolitan centres. Definitions of “home” and “abroad” took very different forms when travelling to socialist Europe in the twentieth century, viewed as they were through the lenses of freedom and women's emancipation. Realizations of selfhood through cultural encounters were also deeply political in terms of comparisons and contrasts between expectations and experiences.Footnote 6 Exploring the nooks and crannies of one's emotional commitment to social justice, as in Chattopadhyay's text, seems to be how sense was made of the vast gap between “real” and “imagined” socialist Europe.Footnote 7

The simultaneous exteriority of the author's encounters with strangers in an unknown land and the interiority of her emotional responses to those encounters compels me to consider BA as memoir, travel writing, and an episodic piece of life-writing.Footnote 8 In her Introduction, Chattopadhyay writes that she first travelled to East Berlin with ideological inspiration, hope, and the dream of seeing and living the socialist society. On her return, she tried to put her memories into words, and published a few pieces in Bengali literary journals such as Desh, Eshona, and Ekhush Shatak, but could not complete a full-length book because of many other involvements.Footnote 9 BA, as a complete text, thus becomes significant for its episodic yet autobiographical handling of a specific set of experiences.

Chattopadhyay writes short, crisp descriptions of life in East Berlin and her colleagues at WIDF, often interspersing them with snippets of her life in Calcutta. This intertwining provokes reflections on the history of the women's movement in India, on the information she gathered from her colleagues about gender-based discrimination in different parts of the world, and on aspects of internationalism in socialist women's history. The author's selfhood becomes enmeshed in these personal experiences as she communicates them to others, and the fusion between individual and collective memory shapes Chattopadhyay not only as a narrator of “other” experiences, but also as a self that is constructed by these experiences. BA becomes episodic life-writing through this interaction, and gains the distinctive characteristics of travel memoir, with the strangeness of the place the author visited and her growing familiarity with it becoming intelligible after a gap of nearly twenty-two years.Footnote 10 The memoir is notable for the details Chattopadhyay provides in terms of her travels across Europe with her husband when he visits her, as well as her travels in different countries of Africa, Asia, and Europe as an official delegate of WIDF during a three-year period; but it also describes East Berlin as it becomes a home away from home, one that she could compare with everyday life in Calcutta before and after her time in Europe.

This retrospective quality is what separates BA from other memoirs by Bengali socialist women. Leaders such as Manikuntala Sen, Renu Chakravarty, Kalpana Joshi, and Kanak Mukherjee remembered their years of participation in the communist movement through autobiographical writings, with the focus often being on the nature of a collective politics of resistance and sacrifice rather than on individual journeys through political experiences in terms of public and private lives.Footnote 11 In these memoirs, travel features only fleetingly, to indicate the international appeal of socialism and to affirm how activists share ideological bonds across borders. Malobika Chattopadhyay's text allows us, on the one hand, an entry point to the largely forgotten international camaraderie of socialist feminism, where representatives from postcolonial locations found institutional mechanisms that allowed them to interact with each other; on the other hand, it allows us to explore the intertwining of outer and inner journeys of an Indian socialist woman. Simon Cooke has drawn attention to the volatile political aspect of the link between travel writing and self-exploration.Footnote 12 Travel as a metaphor for self-exploration can lead to the imposition of an individual's moral landscape on constructing a “strange” foreign land – as in Chinua Achebe's critique of Conrad or V.S. Naipaul's tortuous search for inheritance, which renders India as an “area of darkness”.Footnote 13 The author's ethical responsibility thus becomes especially important when recovering women's history through the braided characteristics of memory and forgetting.

Women's history does not presume an undifferentiated protagonist who has a neat set of submerged facts and emotions that can be excavated in their entirety. Fragmented documents of memory, history, and imagination are intertwined when reconstituting an individual player, and it is more important to comprehend the fragments than an elusive whole. Memories, when written down, become acts of self-reflection, and taken together these create a chain of representations in which remembering and forgetting become interwoven, as it is impossible to remember every minute detail of one's life, even over a short period of time. The act of representation, as Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak has reminded us, involves two processes – speaking from and speaking for – and the delicate differences between them may be confused unless they are carefully sifted through the ethical responsibilities of representation.Footnote 14 In the case of this text and its author, my responsibility concerns both the contexts from which the author drew the aesthetic portrait of her memories of WIDF in East Berlin and a critical review of the context in which the text becomes relevant to women's history. In other words, this article is an effort to understand the ways in which Malobika Chattopadhyay's memories become representative of a particular vision of the world, envisioned from a specific location and bearing the legacy of a social movement that unfolded over a century.

However, it is equally important to outline my motivation for focusing on this text and its author at the outset – as part of the ethical responsibility of representation. Chance encounters or fortuitous events are a not uncommon inspiration for long-term engagement with a specific theme of research, and, in this case, meeting Malobika Chattopadhyay in her capacity as a former Secretary of the Asian Commission in WIDF was one such event. The surprise element of this chance encounter is that Malobika Chattopadhyay was a close friend of my family for over three decades before I knew about her role in WIDF. The access to her text and long conversations with the author consequently did not follow the usual methodology of objective interviews followed by a close reading of the text. Rather, this article draws on personal communication, archival records, reading strategies, and the interrelationship between history and memory.

The first section sets the cultural history of travel and the history of India's connection with WIDF in context. It also develops the specificities of Bengal's cultural connections with Soviet socialism during the Cold War period. The second section describes Chattopadhyay's creation of a home away from home in East Berlin. She remembers her new home, her workplace, her colleagues (many of whom would become friends), her walks in the city, and her conversations with herself as she attempted to understand socialist Europe. These crisp descriptions of people, places, and emotions narrate a complex empathy for socialist ideals and their practices in different geopolitical contexts. The third section focuses on the author's experiences at the Nairobi Women's Forum in 1985, in order to understand the contestations between the socialist and non-socialist world regarding “women's issues”, especially the role of international representatives from WIDF. The concluding section focuses on Chattopadhyay's short Epilogue, which situates the book in the post-socialist world of the twenty-first century.

TRAVELLING POLITICS, TRAVELLING WOMEN: FLUID REGIONS OF TRANSNATIONAL SOCIALIST FEMINISM

Women activists in the Indian socialist movement began to travel internationally, develop political associations, and participate in political conferences as early as the 1920s. Ania Loomba has written about Suhasini Chattopadhyay's travels to Europe from the 1920s to the 1940s and Vimla Dang's brief visit to Prague in the 1940s.Footnote 15 Indian women also visited Paris in 1946 to participate in the first WIDF Congress.Footnote 16 All such journeys indicated participation in a growing transnational socialist feminist organization throughout the Cold War period.Footnote 17 Among the 850 delegates present in Paris, there were four from the All India Women's Conference who represented different regional and national groups: “Ela Reid came from MARS [Mahila Atma Raksha Samiti, based in Bengal], Jai Kishore Handoo represented the AIWC [All India Women's Conference, led by the Indian National Congress], Roshan Barber joined from the India League's London Office”, writes Elisabeth Armstrong, “and Vidya Kanuga (later known as Vidya Munsi) came from the All India Students’ Federation”.Footnote 18 Indian delegates spoke about the specific characteristics of exploitation under colonialism, and argued for the inclusion of anti-imperialist struggles in the fight against fascism. The first WIDF Congress focused on anti-fascist movements, but the voices of Indian delegates made an impact in terms of the broader connections between anti-imperialist and anti-fascist struggles.Footnote 19

WIDF planned to focus on the women of Asia and Africa at its next conference, reflecting a concern for women's conditions in the different contexts of colonialism. A team, consisting of members from Britain, France, the US, and the Soviet Union, visited India, Burma, Singapore, and Malaya in 1948, travelling to Delhi, Bombay, Lucknow, Calcutta, some parts of Assam, as well as a number of Bengali villages. This was part of the preparatory work for the next congress, and it involved meeting the national government of India to get permission to hold it in Calcutta. The Nehru government was at the helm at this time. As Armstrong writes,

Geographically India lay at the center of a visionary conception of Asia that spanned the pan-Arab nations of Egypt and Lebanon as well as the eastern reaches of China and Indonesia, and in the north, the Asian Soviet republics and Mongolia. Jawaharlal Nehru framed these horizons of Asia in a 1946 radio broadcast.Footnote 20

Calcutta was the selected site for the congress because of its centrality in leading anti-imperialist movements since the nineteenth century as well as its significant role in organizing the Indian socialist movement.Footnote 21 Since the seventeenth century, the city had been located on the primary routes of political influence and trade within colonial South East Asia.Footnote 22 The long history of the socialist movement in twentieth-century Bengal covers a huge mobile network from Afghanistan to Dutch colonial Batavia.Footnote 23

The meetings between the WIDF team and Indian government officials were not successful, however, and the meetings with the leaders of AIWC did not meet expectations either. In 1948, the Nehru government was explicitly opposed to any communist initiative, and the Communist Party of India (CPI), after a brief period of legitimate existence in the final years of the British Raj because of the support it had offered during World War II, had again been under severe surveillance for organizing militant peasant movements in Bengal. Since the Bengali women leaders of MARS were also involved in these movements, they were expelled from the AIWC; many were in prison when the WIDF team visited. The city of Calcutta was experiencing large protest rallies, led by the communists, and the national government of India was opposed to giving permission for an international socialist feminist conference to be held in the city.Footnote 24 The following year, four communist women – Latika, Pratibha, Amiya, and Geeta – succumbed to bullet injuries while leading an anti-government protest rally on the streets of Calcutta.Footnote 25

The WIDF Congress of 1949 was finally co-hosted by the All-China Women's Democratic Federation and MARS in Beijing. The role played by MARS, as a regional organization of India, indicates that transnational socialist feminism was being viewed with a different kind of spatial imagination. In spite of the Indian government's refusal to give permission for the congress and the withdrawal of the AIWC from WIDF, MARS activists found a way to participate and to express solidarity. They also became crucial in articulating the historically informed spatial connections between Bengal, Burma, and Malaya as a regional formation, which could be affiliated with WIDF.Footnote 26 Though these regions had recently become territorially defined sovereign nation states when European colonialism formally ended, women were perceiving a regional solidarity that was based on the far longer history of cultural connections. Anti-imperialist solidarity, first raised by Handoo in 1945, was echoed in Beijing when the French delegation presented the Vietnamese delegation with a banner to express their opposition to the ongoing French war in Vietnam, and the Algerian delegation reported how Algerian women as family members of dock workers had stopped French military ships from sailing to Indochina by holding protest marches and pelting the police with stones.Footnote 27

It is also important to remember that the working-class women associated with MARS had little concern for territorial nationhood: for them, the struggle against exploitation had only just begun. For them, drawing territorial boundaries for postcolonial nation states meant displacement and escalating vulnerabilities. This sense of solidarity across the social structures of class, caste, region, and religion was at the core of MARS, and it led to the formation of the National Federation of Indian Women (NFIW) in 1954. WIDF's tenth anniversary brochure, published in Berlin in 1956, notes the extensive participation of women from Cameroon, Nigeria, South Africa, and India in the Copenhagen Congress of 1953.Footnote 28 This event was therefore crucial in forming NFIW and its continued association with WIDF.Footnote 29 The brochure also indicates that India had attained a significant position within WIDF, as Pushpamayee Bose was an elected vice-president.Footnote 30

In 1953, MARS was reconstituted in West Bengal as Pashchim Banga Mahila Samiti (PBMS) (West Bengal Women's Organization) and was affiliated to the CPI. This became necessary owing to the serious losses MARS had suffered when the CPI was banned by the Nehru administration (1948–1952). PBMS also underwent major organizational tension within a decade of its formation because of the Sino-Soviet split in the international forum of communist solidarity. After the Indo-Chinese war in 1962, it became imperative for Indian communists to rethink their affiliation with Soviet Russia. In 1964, a new party – the Communist Party of India (Marxist) (CPI-M) was formed. Members of PBMS did not want to support this as they were involved in issues such as opening girls’ schools, children's welfare, mothers’ rights, and women's reproductive health rights, along with participating in mass movements.Footnote 31 In 1971, however, PBMS split, and the new wing, associated with CPI-M, renamed itself Pashchim Banga Ganatantrik Mahila Samiti (PBGMS) (West Bengal Democratic Women's Organization).

By the end of the 1970s, the Indian women's movement had found its autonomous voice that was able to register protests against violence towards women, and a new feminist scholarship began to emerge with a focus on postcolonial conditions. These efforts were directed towards new tightly knit local organizations with focused agendas that would eventually prepare the ground for a self-consciously feminist critique of the existing leftist political parties. The rising challenges in the following decade from majority fundamentalism, limitations of legal reforms and case-based activism exposed “how fragile was the collectivity based on gender politics and how vulnerable it was to challenges of community, class, and caste interests”.Footnote 32 Amid the beginning of this churning within the women's movement and the challenges from outside, the All-India Democratic Women's Association (AIDWA) was formed in 1981. Elisabeth Armstrong writes that AIDWA shared “deep ties with the Communist Party of India (Marxist)” and remains part of the mass organizations affiliated to the party.Footnote 33 However, as one of the largest women's organizations in contemporary India, AIDWA maintains a certain degree of political independence.Footnote 34

The gendered affective political subject, however, survived to a certain extent in the Indian context within the discourses of transnational socialist feminism. An emotional commitment to socialist politics as women, as socialists, and as socialist women has endured in a particular generation. The affiliation with WIDF became a crucial link with international socialist feminism for the next three decades, and Malobika Chattopadhyay notes that before she accepted the position, the leaders of NFIW – Aruna Asaf Ali (Figure 1), Vimla Faruqi, and Bani Dasgupta, who had served at WIDF – informed her about the requirements of the position.Footnote 35 Chattopadhyay spoke to these leaders about Indian government policies on women's welfare, on the available data on various aspects of being a woman in India, and on the working of WIDF in Delhi, while her visa and passport were being sanctioned. The opening pages of BA are testament to her internal dialogues regarding the seriousness of her responsibilities and her mental preparation for performing the duties that would, for the first time, connect her political ideology and activism with an international institution. Her book, therefore, stands at a crucial historical juncture, between the twilight years of European state socialism, the beginning of a new chapter in South Asian postcolonial feminism, and the initial period of an autonomous women's movement in India.

Figure 1. Indian communist leader Aruna Asaf Ali, being felicitated by Freda Brown. Chattopadhyay is on their right along with one colleague.

Photograph from Malobika Chattopadhyay's personal library.

Chattopadhyay's experiences are also part of the history of the culture of travel, from the perspective of a woman travelling to and from socialist Europe. On her first international journey to Germany, she had a stop at Moscow. She writes:

Moscow airport is huge, beautiful. It is almost entirely made of glass. But it was silent, lifeless. There were people. Flights were arriving and departing. But nowhere was a sign of life, of human conversation. Intermittently I could hear noises from the moving footwear of travellers. Police, the officers at immigration, waitresses and airhostesses were cold, nearly rude to everybody. […] Amidst all my unruly thoughts I could feel an excitement. I am sitting in Moscow, and I shall come to Moscow again in the coming months. Lenin's Moscow, in whose name, we have marched so many times on the streets of Calcutta.Footnote 36

Even though Chattopadhyay admits to herself that she had wasted some money by sending a telegram to the Soviet women's organization to meet her at Moscow, as no one from the organization had come to the airport, her excitement was undeniable. This enthusiasm about an airport transit visit to “Lenin's Moscow” was possible only in the context of the history of the socialist women's movement in India.

Her subsequent visit to Moscow happened in September 1984 as a representative of WIDF at the International Congress of Textile Workers. In her own words:

I was a little anxious about this visit. But anticipation clearly overrode the anxiety. […] On my way to Berlin, during the stop over at Moscow airport I had my first impressions, but one cannot know or learn about a country from its airport. I set off with a lot of expectations about Lenin's country, Stalin's country and Moscow, the citadel of October Revolution. In the flight I kept on thinking about our days in Calcutta streets, shouting slogans for Soviet socialism. Soviet – the savior of the proletariat, a great friend of India and the third world, the leader of the socialist bloc! Soviet, where Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, Gorky, Mayakovski were born – I am going there!Footnote 37

Chattopadhyay's sense of disappointment continued, however. Her expectations were not matched in her later visits to Moscow and to Tashkent (Figure 2). The most interesting aspect of her delight during the journey to Moscow in September 1984 is the list of names she mentions – from political personalities to authors, novelists, and poets. While Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky predate Soviet socialism, Gorky and Mayakovski represent different kinds of complexities within the idea of socialist culture in Soviet Russia. The continuous chain of cultural icons that she creates in her imagination is less about Soviet socialist culture inside Russia and more about its reception in India. She had read these authors’ works and had known about them ever since her childhood, creating an imaginary world of Russia's socialist society. The affective register of imagining a foreign land, especially an idealized society (idolized to a certain extent), indicates a particular view of colonial modernity in India.

Figure 2. Malobika Chattopadhyay with Uzbek women in Tashkent.

Photograph from Malobika Chattopadhyay's personal library.

The framework of colonial modernity, utilized by feminist historians of South Asia to explain the effects and impact of the British Empire on women in colonial and postcolonial times, considers the culture and practices of travel as important axes for the making of the “self” as opposed to the “other” through constructions of home and the world. “In the European culture of travel”, writes Inderpal Grewal, “mobility not only came to signify an unequal relation between the tourist/traveller and the ‘native’, but also a notion of freedom.”Footnote 38 This idea of freedom was strung in a metonymic chain of meanings alongside “home” and “civilized”. “Abroad” referred to despotic rules of unfreedom suffered by natives, while home was civilized and free. Such spatial meanings, however, were disrupted when English-educated “natives” used them during their travels through the imperial centre. The counterflow of women travellers to England and Europe had produced a distinctive narrative of freedom in thought and activity, making England/Europe a space where they could explore their selfhood vis-à-vis gender politics at home and abroad (Figure 3).Footnote 39

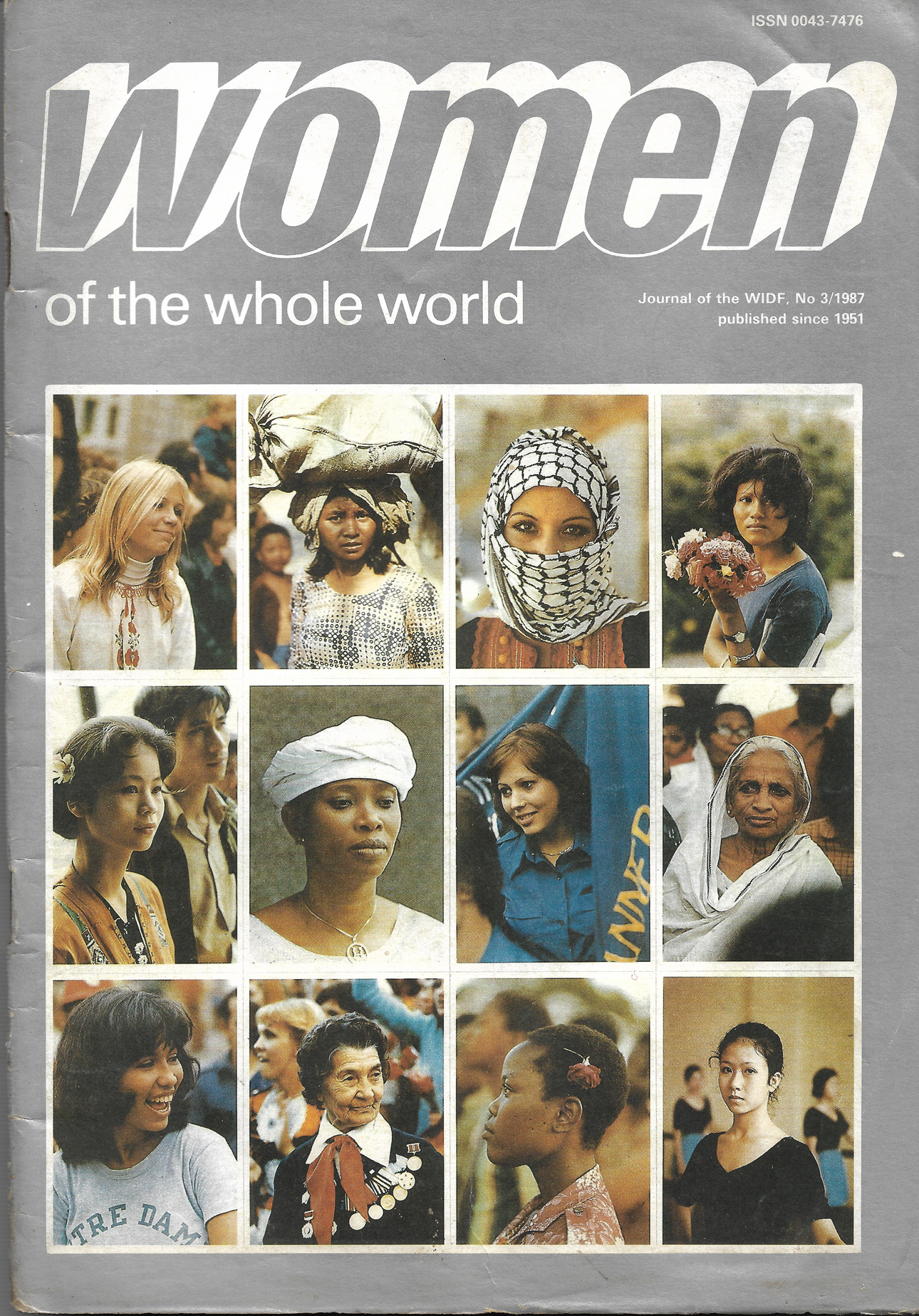

Figure 3 Front cover of the magazine Women of the Whole World, the journal of the WIDF.

From Malobika Chattopadhyay's personal library.

For colonial Bengalis, visits to England and increasingly to Europe were more about observing the reality of England/Europe as opposed to the hyperreal image of England/Europe that they had formed through colonial education policy. Their travelogues are interesting because of the preconditioning of their travel experiences, where the constant comparison between the “real” and the “image” constituted the narrations of their experiences. A couple of examples will indicate the process of “colonization of experience” (italics in original).Footnote 40 Shibnath Shastri, an eminent social reformer in nineteenth-century Bengal and a scholar, went to visit Devizes during his travel in England in the 1880s, and when he heard a skylark for the first time in his life he immediately thought of Shelley.Footnote 41 Krishnabhabini Das visited England in 1882, and in her travelogue she noted unequivocally that she had experienced her greatest freedom during her years there. In a chapter titled “Empress Victoria and her Household”, Das mentions the importance of parliament in imperial governance, citing how the queen was running the entire British Empire with the help of parliament “with fairness, justice, and discipline”.Footnote 42 This reference is suggestive of the “freedom” in “civilized” England, since “parliamentary rule signified representational politics and the voice of the citizens”.Footnote 43 Grewal argues that English women, even without any representation or voting rights in the parliamentary system, participated in the discourse of “civilized freedom” when they travelled abroad, precisely because their “home” was defined by those two ideas. However, for “native” women travelling abroad, the ideas of freedom were fraught with competing discourses of progress, tradition, and nationhood. From the 1870s, social reform movements based on the issues of women's emancipation were going through a critical period in British India, as reformers made efforts to forge an agreeable relationship with a gradually emerging nationalism. Krishnabhabini Das's appreciation of imperial good governance and her assurance to her readership that the Empress Victoria did not wish India ill contains an interesting twist in her conceptualization of “home”. Das inhabits the intersecting points between home and abroad as she both celebrates and laments the “rulers” of civilized freedom. It seems that the multiple spatial scales of the British Empire of her times constructed her sense of belonging, which contained a yearning for a civilized home that would ensure freedom.

Partha Chatterjee describes such travelogues as “sincere declarations of love by a modern Indian for modern Europe”.Footnote 44 This “love” is layered more with aspirations towards the object of love than about the surprising elements of experiencing something new. Nearly a century later, Chattopadhyay's travels to socialist Germany, and especially her visits to Soviet Russia, bear a distinctive legacy of the aspirational love for England by the Bengalis. The object of love, however, had been transformed from modern Europe to socialist Europe. While the nineteenth-century modern Bengali's aspirational love for modern Europe was framed by colonialism, the love for socialist Europe was characterized by a sense of solidarity. The affective register had undergone a major shift through a particular kind of familiarity with Russian literature and culture. This shift certainly enjoyed tacit governmental support, which was Soviet aligned in the Cold War period and allowed the flow of Soviet and European socialist literature and cultural ideas and practices.Footnote 45

The translation bureau in Moscow provided excellent books and magazines at affordable prices in various Indian languages such as Bengali, Hindi, and Malayalam. Translators, based in Moscow, often performed the crucial task of introducing socialist aesthetics and culture among publics who were hitherto unaware of them. Here, I would like to refer to Subhomoy Ghosh, who spent six years (1962–1966) as a Bengali translator in Moscow and who wrote short features about his experiences of living in Soviet Russia for Bengali literary magazines such as Visva-Bharati Patrika, Anandabar Patrika, and Desh. He wrote about Russian ballet, theatre, poetry, music, literature, and architecture alongside politics, and also the reception of Bengali cultural icons such as Rabindranath Tagore and Nandalal Bose in Soviet Russia. Ghosh's short features or “dispatches” were later collected in a book titled Moskor Chithi (Letters from Moscow) and explained in accessible Bengali – for example, “Bolshoier Romeo Juliet” (Romeo and Juliet in Bolshoi), “Tolstoy Sadan” (Tolstoy Museums), “Shostakovicer Notun Symphony” (The New Symphony of Shostakovich), and “Leniner Library” (Lenin's Library).Footnote 46 The names of literary figures whom Chattopadhyay remembers on her flight to Moscow resonate with the themes of Ghosh's “dispatches”. These names and their works became familiar in Indian communist households from the 1950s and 1960s. The affective relations with Russian culture along with socialist politics formed the kernel of emotional political commitment to socialism, where Moscow was not only the name of a modern European city, but also a home from home for Bengali socialists. Chattopadhyay's disappointment with Moscow is thus replete with doubt – whether she had misunderstood the city and its dwellers – and she almost heaves a sigh of relief when East Berlin becomes a second home for her, replacing one dreamland with another.

“ZWEITE HEIMAT”: MALOBIKA'S SECOND HOME

On 26 July 1984, Malobika Chattopadhyay arrived at Berlin. Surjit Kaur, who was leaving the position she had come to take, and Gizela, one of the German secretaries at WIDF, received her at the airport. Surjit Kaur's daughter Roli stayed back after her mother left for India, as she was studying in the final year of her undergraduate course in Berlin, and Roli became almost a foster daughter to Chattopadhyay – a relationship that has lasted for three decades. Gizela also became more than a colleague over the months. On Chattopadhyay's first day in Berlin, Gizela and Surjit took her to her accommodation at Albert Hoeschler Strasse, showed her the flat, and taught her how to operate kitchen devices. They had already put some food in the refrigerator for her. The flat was her address for the next three years, and socialist Germany was, in the words of her German colleagues, “Malobika's Zweite Heimat” – second home.Footnote 47

The descriptions of this second home are detailed – the rather large hall with sofa, reading table, television, wardrobe; the bedroom with folded blankets, sheets and pillows; the huge glass front of the hall, covered by a beautiful curtain that reached down to the floor, and the balcony outside the glass front; the kitchen with an electric oven; the spacious washroom complete with a bathtub; even the tall mirror on the side of the wardrobe behind the front door of the flat. All are described with crisp precision. Such details serve the purpose of visualizing Chattopadhyay's “home”, but they also provide a set of images to envision how she would occupy these spaces for the next three years. References to the flat occur regularly. Her husband visits her in Berlin during the summer and autumn of the next two years; Roli stays with her; Roli and her young friends – mostly Indian students in various universities and technical institutes in East Germany – spend weekends with her. Chattopadhyay gave them the keys when she was at the office, and on her return home she was greeted with tea. During her first Christmas vacation, Roli and her friends came over, cooked for her, took her out for lunch or dinner, or simply for walks, and kept her cheerful as Berlin became covered in thick snow and fog. During the festive seasons, she and her husband accommodated Roli's friends in the tiny space, many of them sleeping on mattresses on the floor; and they played Bengali, Marathi, and Hindi songs on the gramophone, often singing along. With so much detail, the flat becomes a lived space instead of anonymous accommodation in a foreign land.

One of Chattopadhyay's young friends, Radhakrishna Upadhyay, a student of computer science in Ilmanau in southern Germany, once brought his German friend Ube Stoyber to her flat. Ube became close to her, and whenever he came to Berlin with his girlfriend Karin they stayed at her flat. Chattopadhyay's description of this young German man contains a sense of empathy:

Ube Stoyber was an exceptional character. An extremely introvert person and a thorough intellectual. He worked as a male nurse in Ilmanau. But, whatever may be his profession, I have always seen him reading. He would be carrying a volume of Dr. Radhakrishnan's philosophical writings, or a copy of the German translation of Tagore's novel Home and the World. He had boundless curiosity and interest about India. When Jyoti [Malobika's husband] came to Berlin he became great friends with Ube. I used to tell Ube that I would send him sponsorship when I return to India, that he should come and stay with us. His rather aloof reply was – such a thing would never happen. They do not have permission to travel outside the socialist bloc.

This introvert, reserved young man had an attraction. Mahesh used to teasingly call him “faqir”.Footnote 48 He quite liked to be called that. After I came back to India I sent him a letter of invitation. By that time, the Berlin Wall had fallen, there was no “east” and “west” in Germany. When I did not get a reply I asked Mahesh and his friends. Mahesh replied that Ube had passed away. He had a wish to travel outside the socialist bloc and when there was no socialist bloc he had travelled out of this world. We could not bring him to India. Jyoti and I always regretted that.Footnote 49

The empathy and pathos in this memory of Ube Stoyber is emblematic of Chattopadhyay's compassion for many of her German friends. During a Trade Union Congress on the outskirts of Berlin, she met Ursula Rabe, an English interpreter. They discovered they enjoyed each other's company during breaks from official sessions, and they continued to meet after the Congress. Ursula worked at a bank in quite an important position. She was a little older, but as their friendship developed she became “Ula” to Chattopadhyay. Her office was right opposite the WIDF office in Unter den Linden. They often met at the end of a day's work and had dinner, accompanied by long conversations. Ula's husband had died of cancer and her grown-up sons lived in other cities. Her father had fought in World War II and she hated fascism with a rare passion; but she resented the orthodox restrictive rules of East Germany with an equal passion. She had been to India a couple of times, visiting as an interpreter with German delegations, and wanted to learn more about the country, the culture, the people, and to travel around. Chattopadhyay offered invitation to her on her return to India – “come over when I go back and together we shall go to the Himalayas, the forests, Taj Mahal, Khajuraho, Ajanta […]” but Ula would always reply with great bitterness that she would never be able to travel outside the socialist bloc.Footnote 50 One can hear an echo of Ube Stoyber's reply to her similar offer. The quiet resignation of Stoyber and impassioned bitterness of Ursula Rabe opened Chattopadhyay to the limitations of socialist societies, compelled her to recognize the nature of disaffection from the socialist state among the people of Germany, and to offer, in her individual capacity, solace in friendship.

Glimpses at Chattopadhyay's impressive circle of German friends would remain incomplete without her memories of “Clara and Werner, one was seventy-five, the other was seventy-seven, bound in deep friendship and love with each other. Their story was far more romantic than any Hollywood love story”.Footnote 51 Chattopadhyay writes the “story” of their lives – young lovers in pre-war Germany who became estranged during the war as Werner had to leave for the Russian front just before their marriage, their decades of loneliness after the war, and their fruitless search for each other, and a chance meeting in Berlin when both were in their sixties – with a rare compassion. It seems that Clara and Werner's love symbolized the national tragedy of war-torn Germany, where the denouement comes after such great sorrow that reunion remains under the shadow of estrangement. Before Chattopadhyay left for India, “they came to my home. A gift of a tea-set and a hand-written card are so precious to me that I have kept them as a reminder of the human capacity to survive the tragedy of war”.Footnote 52

Chattopadhyay's colleague Hildi Hartings introduced her to Clara and Werner. Hildi, who used to sit in the next room to her office and worked for the Asian Commission, remained a constant presence during the three years of her stay. It was Hildi who took her around the office on her first day, introducing her to other colleagues, and who also took her to shops and markets, helping to make her familiar with the city's roads and transport. Before she became confident enough to go to the office in public transport, Chattopadhyay used to travel there with two of her colleagues – Mita Seperepere from South Africa and Victorin from Congo – in a car organized by the office. Ho An Ga, her Vietnamese colleague, came from a struggling peasant family, while her Mongolian colleague Deze came from a well-off family; both became quite close friends.Footnote 53 There are short descriptions of the nature of socialist politics in the countries from which her friends came, with a special emphasis on African countries. There was a special bonding with Mita Seperepere, as they both held Mahatma Gandhi in great respect, and Chattopadhyay's conversations with her colleague are testament to her enduring esteem for anti-Apartheid activists. As she started learning German, mastering everyday conversation after a few months, her closeness to Sabina, Birgitte, Gizela, and Katia – her German colleagues – increased. There are mentions of Rita from Finland, Valeria from Soviet Russia, Therese Noor from Lebanon, and two representatives from Iraq, whose names she does not disclose for reasons of confidentiality and their safety.Footnote 54

Chattopadhyay's work at WIDF is not described in detail in any one place, but rather it is imbricated in everything she saw, did, and felt. She started her work by familiarizing herself with the history of WIDF, pulling out old files from the archives and preparing notes for her future work on connecting the issues of Indian women with WIDF policies. Her first experience of listening to colleagues from different countries through translators was a little intimidating, as she realized that her own interventions and reporting would soon be disseminated in the same manner; that each of her words would be recorded and filed away for future generations of secretaries.Footnote 55 Her nervousness, however, soon vanished as she became busy in the office. She started attending emergency meetings when new or complicated issues emerged, participating in discussions and conferences on international contexts of peace and conflict, and attending to special guests.Footnote 56 Her time flew by when she had to submit or work collaboratively on a special report. After her trip to Moscow for the International Congress of Textile Workers, Chattopadhyay had to submit a report for discussion. When Valeria, the Secretary of International Commission and Soviet Union, praised her report for her ability to connect the ideology of WIDF and the principal themes of the International Decade for Women (1975–1985) with the main issues discussed at the Moscow Congress, she felt the sense of a different kind of achievement.Footnote 57 It was her first step towards institutionally engaging with women's global issues – the rest of the world had finally started to take a definite shape.

In the WIDF office on Unter den Linden, events both large and small happened regularly, everything from celebrating a colleague's birthday with flowers and cake, to organizing trips around the city, to visits to museums, opera, or theatre.

Chattopadhyay's visits to the monuments and memorials that dotted the city are informative and lucid, and express part of the cultural life of Berliners. Her rapturous appreciation at watching Brecht's plays at Berliner Ensemble – The Threepenny Opera in particular – is followed by her experiences of watching Brecht's translated plays in Calcutta.Footnote 58 She does not forget to mention that watching German productions of Brecht's plays inspired her to grasp the genius of Ajitesh Bandyopadhyay, one of the most significant translators and producers of Brecht's plays in Bengali. As she became familiar with the social life of Indians living in Berlin and became acquainted with the Indian ambassador, Chattopadhyay started going to concerts and plays by Indian artists – such as the Calcutta Youth Choir; a play by Utpal Dutt, one of the foremost socialist theatre artists of India; and Indian classical music concerts. Listening to Pete Seeger and Bob Dylan at the Berlin Music Festival takes centre stage in her cultural experiences in Berlin. Such experiences, during which she became a part of the collective social life of her second home, culminate in her participation in various citizens’ marches and processions to mark May Day, the anti-Fascism day on 9 September, Martyrs’ Day, and Women's Day. Of all these marches, she was most overwhelmed by the one on 13 January to commemorate the martyrdom of Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht. Her description conveys the sense of camaraderie that comes through sharing idealism and respecting difference: “In the bitter cold of January, on the snow-covered roads of Berlin thousands of people walked, and I, the only sari-clad figure among them, were a great novelty for the German television.”Footnote 59 Though her colleagues made fun of her fifteen minutes’ fame, she knew that they also appreciated the solidarity of a comrade from a far-flung country.

Participation in such collective cultural experiences, however, was interspersed with solitary walks along Magdalen Strasse to Frankfurter Allee, or towards Listenberg station, or along Babel Platz. Her trips to West Berlin across the Wall were also experiences of lonely travel, laced with fear and suspicion. She describes the humiliating searches and threatening glances in great detail for her readers at home. Her critical observations about the “Dollar Shops” at the border are significant. For her, they represented the superficiality of capitalist democracy and yet, she admits to her readers, the post-war generation of socialist Germany fell for that enticement as they had, tragically, been dissociated from the history of socialist politics and struggle. Coming from an impoverished Third World country, she could understand the lure of consumerism, but she could not fathom the desperation for consumer goods when basic social justice had already been achieved.

SHOTO POTHE NAIROBITE: A HUNDRED WAYS TO NAIROBI

Before going to the Women's Forum in Nairobi in 1985, Chattopadhyay had earned her stripes as a representative of the Asian Commission of WIDF in various international forums – in Moscow, Athens, and Baghdad.Footnote 60 Her observations in each of these conferences contain critical appreciation of the places, people, and issues at stake, but she is astute enough to point at the disconcerting factors without hesitation. In Moscow, she found the conference sessions educational, but the overall social environment stifling. Athens was her introduction to a very different culture, where she found affinities with her home country in loud debates, passionate ideological declarations, and easily formed friendships in conference halls, in collective bus rides from one venue to another, even while travelling through public transport on the city streets. Her Baghdad experiences were an entirely different kettle of fish, to use a colloquial term. The conference took place amid the ongoing war between Iran and Iraq, and she found not only the repeated emphasis on the pride and glory of Iraqi history disturbing, but also the shiny new hotels and sprawling conference venue with an excess of food and beverages perplexing for a country torn by conflict. She marked the exaggerated hospitality of the Iraqi government as a sign of Saddam Hussain's populist politics, rather than his government's adherence towards social justice.

Chattopadhyay also participated in a preparatory conference in Vienna before Nairobi to sharpen the focus of WIDF. A vignette from her experience at this conference introduces the dividing lines between the non-socialist countries and the socialist bloc. This experience is also significant because it almost pre-empts the historic outcome of Nairobi. While participating in the workshop on education, she articulated her thoughts on the development of education in India, and argued that “after two hundred years of British colonialism my country is reeling under misery, exploitation, and wretchedness; what can be the feature of education in my country than disorder and confused policies”.Footnote 61 After the workshop, Edith Bradshaw, who was part of the delegation from Great Britain, came up to her and said: “Why are you Indians still unable to get out of the colonial hang over? Did India not make any progress during British colonialism? It was the colonial government who made the railways and many other reforms!”Footnote 62 Chattopadhyay writes that her response to this was probably a little rude. But she had to tell Bradshaw that the British colonialists crossed oceans and established the empire in India not to introduce reforms. Rather, it was an oppressive regime, killing millions of Indians, which aimed to make as much profit as possible – and it was only for that reason a few hundred kilometres of railways and mechanized ports were constructed. However, the hostility in this exchange of words ended after a prolonged debate in a friendly shaking of hands. The ability to recognize and understand the historical impact of colonialism and imperialism on Third World nations was the key outcome of Nairobi – that political stability and economic policies directed towards social justice were the cornerstones of addressing “women's issues”.Footnote 63

The title of the chapter on Nairobi is “Shoto Pothe Nairobite” (A Hundred Ways to Nairobi), underlining the great diversity of the forum. Chattopadhyay writes:

Groups of women were arriving at the Nairobi airport, were walking on the streets, in the parks, in the markets, in the famous Kenyan safari, in tour buses – women were everywhere. During the ten days of Forum and Conference, the university spaces of Nairobi, every conference venue in the city were filled with women representatives – they argued, debated, gave slogans, sang songs.Footnote 64

This description finds resonance in the way Bina Agarwal remembered Nairobi in 1985 as a celebratory conference, with images “of African women dancing spontaneously on the green spaces between the meeting rooms”.Footnote 65 Agarwal also confirms that unlike two previous such conferences, in Mexico in 1975 and Copenhagen in 1980, Nairobi celebrated the arrival of “Southern women's movements, including India's”, and attracted widely recognized women activists and authors such as Angela Davis, Nawal El Saadawi, and Rigoberta Menchu.Footnote 66 That it was a historic occasion was clearly evident. The Nairobi forum became “the site of over 1,000 activities, including panels and workshops; a multitude of cultural events; a film festival; a Tech N’ Tools Appropriate Technology Fair; and the Peace Tent an arena of discussions of feminist alternatives for peace”.Footnote 67 In front of nearly 14,000 representatives from more than 150 countries, it became quite clear in 1986 that it was not possible to have specific “women's issues” with universal applicability, but rather that these issues are interwoven with economic and political contexts, with militarized violence and peace processes, and within the historical trajectories of the participating nation states or non-governmental organizations.Footnote 68 Chattopadhyay mentions that in the context of discussions on ecology, the Bhopal gas tragedy, which happened in 1984, was especially condemned, and a resolution was taken to demand compensation from Union Carbide, the owners of the leaking pesticide plant.Footnote 69 Women's conditions in conflict-ridden or in post-conflict societies inspired many spontaneous sessions on the impact of civil war in Ethiopia and Afghanistan, the necessity of bilateral talks between Iran and Iraq, between Israel and Palestine, and between India and Sri Lanka, and on the aftermath of imperialist wars in different Asian countries.

In the Nairobi film festival, features on the progress of Cuban women attracted attention; documentaries on women workers in the rubber plantations of Sri Lanka highlighted structural inequalities in the gendered division of labour and the sexual exploitation of African women in the French colonies; and those focusing on the courage of Palestinian women in the resistance movement opened up different historical episodes in women's lives across space and time. Chattopadhyay mentions that the delegates unanimously condemned the Bhopal disaster. She devotes special attention to the Peace Tent and its complexities, indicating the keen political sense that led her to identify important issues that reflected points of confrontation between socialist and non-socialist blocs.Footnote 70 WIDF was one of the principal organizers of this space. At the front of the huge tent, covered in white and yellow cloth, a plaque read “Nuclear-Armament-Free Zone”, while inside cultural events took place to celebrate peace. The fundamental element of all the events at the Peace Tent was opposition to the imperialist-capitalist complex; a view that the ideals of socialism would eventually emerge victorious. Its popularity was not appreciated by the Kenyan government, which made several attempts to close it down, and it remained open only because of women's determined support.

Chattopadhyay also met many of her personal heroines – Vilma Espin Castro (a Cuban revolutionary feminist leader), Valentina Tereshkova (a Soviet woman cosmonaut), and Angela Davis (an American political activist, scholar, and author). Possibly because of her characteristic humility, we are only privy to her endearingly star-struck and overwhelmed expressions when she was invited to sit in the same room as them or share discussion forums, rather than any personal conversations, although the hilarious occasion when she met Angela Davis in the shower is recounted. In her inimitable capacity to traverse the personal and the political with ease and humour, Chattopadhyay narrates her experiences in the common showers at the rest rooms for women delegates:

It was a long room fixed with a line of showers where women could wash themselves. Women from Asia and Arab countries were trying to bathe under as much cover as they could manage. But the American and European women took showers while animatedly talking to each other completely without clothes. Though many of us, including me, felt quite embarrassed, Angela Davis or Margo Nikitas or Frista from Germany would warmly greet us while bathing!Footnote 71

The discourses around women's bodies are hinted at. However, true to the spirit of her travelogue, Chattopadhyay does not intellectualize her experience at the shower. My informed guess is that she avoids stereotyping through this strategy, and this works for the readers too as the humour humanizes icons, with a gentle nudge towards the corporeality of the body and the banality of an everyday ritual.

MEMORIES OF A DREAM? OR, GIFTS OF A LIFETIME

Chattopadhyay added a brief Epilogue to her text, describing her experiences during her journey back to Germany after twenty-two years, in 2009.Footnote 72 She felt that very few things had changed spatially in East Berlin other than the removal of the three-storey-high Lenin statue from the centre of the city. Yet, she knew the transformation across the whole country was remarkable. She wanted to understand the changes through her German friends, and she could meet only a few of them. The most poignant meeting was with Hildi Harting, her greatest friend in WIDF. The two women exchanged stories about the changes in their personal lives, but Harting was silent when the unification of Germany came up. Chattopadhyay writes that she could partially understand the reticence of her friend. Harting had never wanted unification at the cost of socialism. The naked aspirations for capitalist opulence among her compatriots and the gradual disintegration of the socialist ethos under the pressure of individualism had turned her bitterness into silence. As her reader, I cannot but juxtapose the resentment of her other friends such as “Ula” Rabe towards the restrictions in socialist Germany with Harting's stern resolve to refrain from discussing unification. Chattopadhyay could not trace Ulrike in 2009. We may wonder whether she was happy in unified Germany, galloping along with the capitalist West.

As she walked down Unter den Linden after two decades, Chattopadhyay remembered her other friends at WIDF, especially Mita Seperepere from South Africa. She had not met Mita in the post-Apartheid era and could only think about Mita's triumphant return to South Africa after long years of exile. She wanted to congratulate her friend for their successful struggle against possibly the most oppressive regime in the twentieth century. It was at least one victory Chattopadhyay could be happy about while sitting on a bench in a park in Berlin. She also remembered Solidad, the young woman from Chile who had fled to Europe after the fall of Salvador Allende and become a Chilean representative at WIDF. Solidad and her husband decided to go back to Chile in 1985 to participate in the Chilean democratic struggle, and told Chattopadhyay before leaving that they must go, knowing fully well the dangers awaiting them, because it was a struggle every Chilean had to fight. “I remembered”, writes Chattopadhyay, “that my respect for Solidad increased immensely after listening to her rationale for returning. Solidad, you succeeded in your struggle, finally democracy could again be established in Chile. I hope all of you are well”.Footnote 73 Faces of her Afghan, Palestinian, Arab colleagues passed in front of her eyes. She wondered “What were they doing in the post-socialist world? Were they continuing with their struggles for an equal and just society? How much are they suffering under the macabre Taliban rule?”Footnote 74

Her heart was heavy, but it was full to the brim, too. When she had started her journey, twenty-two years before, she had been full of doubt; now she was weary with worries about her so many colleagues, nay, friends. These were friendships gifted to her by the camaraderie of international socialist feminism, which in the institutional form of WIDF has vanished from the face of the earth. But the lifelong attachments forged while working in the WIDF office remained. Chattopadhyay was calling out to her far-flung friends, even though they could not hear her. As Rebecca Schneider would say, “the past is a relation” – “the antiphonic back and forth among bodies across different times and different spaces” dislodges the linear progress of time, and the past reappears at the juncture between present and future.Footnote 75 Schneider's reflections make it possible to situate Chattopadhyay's call to her friends, through the pages of her travelogue (written in a language that probably none of them understands), as a gesture that calls the past a relation of friendship, a personal memory, and a collective with an agenda for women's emancipation. The affinity to feel for the struggles in distant lands and the right to worry about friends in countries she had not had the chance to visit was the achievement of her emotional political commitment. In this sense, her gesture of recalling her friends and her worries about their well-being becomes the gesture through which the past holds the present, or even the future, accountable. Maybe it was enough, she thought, “to start to dream anew”.Footnote 76