Canonical histories of the Vikings often describe them as lawless barbarians who descended on Europe like a plague.Footnote 1 From the perspective of the clergy who recorded the invasions in England and elsewhere, the Vikings were a stateless, pagan people more intent on loot and plunder than on effective political rule. There is a measure of truth in this view. In the early Viking Age, the Danish and Norwegian armies that attacked England came from societies that were less centralized than those they attacked. Yet, modern scholars of the period note an interesting phenomenon. The Viking raids, and especially the conquest of England by Cnut and his father (in 1015–16), stimulated a period of intense state-building by the Danes and Norwegians at home. The Vikings who raided England at the end of the eighth century were not the same Vikings who ruled England and Normandy by the eleventh.Footnote 2 They had raised standing armies and fortifications back home, were minting currencies to control the economy within their territory, and made the first steps toward national law codes and judicial institutions. Victory had changed them.

The dominant bellicist theory of state formation emphasizes that early states had an advantage in war. These innovative political units either conquered other societies or incentivized other societies to adopt their own state-like institutions. This competitive process ultimately led to convergence on the state as the dominant organizational form of political life.Footnote 3

Viking state formation in the Late Middle Ages presents a puzzle for the conventional wisdom. Consistent with the bellicist theory, a period of intense warring also saw intense state-building. However, the competition mechanism—that states emulate more successful states in order to compete—fares less well. It assumes that political units further along the path toward state formation outcompete others; losers adapt by emulating the stronger units or are selected out of the system. In cases like the Vikings, however, the opposite pattern occurs. The winners emulate the losers. As we describe, English economic, military, and political policies were exported to the Danes and Norwegians after the English were defeated on the battlefield. In short, the competition mechanism appears unable to account for key features of the historical record.

We build on an emerging literature that posits that diffusion, rather than competition, is a key mechanism in early state formation. A diverse new literature on both East Asia and Europe posits there are other means by which communities learn and become states, emphasizing the role of religious institutions in Europe or other elite networks in East Asia.Footnote 4 We refer to this as a diffusion-based mechanism. While there is disagreement within this literature on key elements of the nature of diffusion, it accurately notes that reforms leading to a modern state diffused through a social process of learning. This process of diffusion is explicitly seen as an alternative to bellicist theories.

Our central argument is that war and diffusion are not alternative accounts of state formation. We describe a diffusion mechanism for bellicist theories of war. We build on the work of scholars who note that although some periods of intense state-building followed major wars, not all did. This diffusion mechanism hinges on changes in social conditions brought about by major wars. War disrupts societies. It encourages migration, shatters social structures, and often provokes changes in political and economic leadership. Political elites, especially in the medieval and early modern periods, were afforded opportunities to learn about the societies they invaded; when conquest was successful, they sometimes found themselves atop new political structures they had to learn to navigate. When strong political units defeat and conquer units with state-like institutions, mere exposure to these institutions can be a potent mechanism for adoption. In such cases it is not the weak who emulate the strong, but the strong who emulate the weak.

This paper examines the validity of the theory through a comparative case study of Nordic political units from the dawn of the Viking Age to the end of the High Middle Ages (CE 800–1300). More specifically, we assess the timing and sequence of state-formation processes in Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and Iceland, using new scholarship from the fields of history, archeology, and numismatics.Footnote 5 We show that key processes of state formation happened in Denmark and Norway in the aftermath of successful raiding, settlement, and conquest in what is today England. These Viking raiders and conquerors adopted early state-like institutions in military, legal, and economic affairs which early English kings had established (most prominently, King Alfred of Wessex). Sweden lagged in state formation because it primarily expanded eastward, into areas without state-like institutions. Iceland, which did not initiate any processes of state formation prior to its absorption into the Norwegian kingdom, did not engage in much raiding and conquering.

This paper makes several contributions. First, we provide a new theory of state formation, bridging a gap between two prominent strands of literature. We argue that this theory provides a more realistic understanding of key state-formation mechanisms. Second, by bringing in recent revelations from scholarship outside the social sciences, the paper offers a more accurate understanding of key cases in the state-formation literature (that is, the early kingdoms of Northern Europe), as well as clarifying the timing and sequencing of state-formation processes. Third, the paper sheds light on a key puzzle in the social science literature, which is the extraordinary variety in state size during the Middle Ages and early modern period. A number of theoretical approaches expect a convergence on large state size in this period, yet no meaningful convergence happened.Footnote 6 We argue that this is because early and modest improvements in state capacity do not create a consistent advantage in warfare and the ability to conquer others. Possession of state-like institutions is only one of many factors that affect success in warfare. As the empirical sections show, not only are political units without advanced state-like institutions able to survive challenges by advanced states, but they successfully conquered the most advanced state in Europe.

The dynamic we describe in this paper may help make sense of the ways other great conquerors—the Mongols, the Romans, the Normans, and others—incorporated the institutions and practices of those they conquered, and subsequently diffused those institutions further. Our theory of learning, which emphasizes how winners emulate the institutions of losers, stands in contrast to conventional accounts, where the learning is mostly done by losers after humiliating defeats and failures.

The Origins of the State

Scholarship on state formation is often broadly concerned with explaining the initial creation of state-like institutions and the gradual convergence of political units on institutions that we associate with high state capacity—in other words, explaining why states arose and why they became the dominant organizational form in the international system.

A substantial debate has emerged over the causes of state formation. We explore the link between two approaches: bellicist and diffusion based. The bellicist theory, which emphasizes war and competition, is the dominant framework in the literature.Footnote 7 However, recent scholarship emphasizes the diffusion of organizational templates and practices through learning and emulation.

Theories of War and Competition

The leading proponent of the bellicist theory of state formation is Charles Tilly. In his view, selection and competition made the modern state the dominant organizational form in the international system.Footnote 8 The primary causal driver of state formation is warfare. Preparation for war, the experience of war, and heightened insecurity led states to extract the means of war from their populations, which drove institutional innovations in taxation, administration, and military organization. Political units with an advantage in extracting the means of war outcompeted other states.

The bellicist theory has three key steps in its theoretical logic. First, state-formation processes should take place when states prepare for war, engage in war, or generally face security threats and military competition. These conditions prompt rulers to seek to efficiently extract the means of warfare. Second, states with greater state capacity are usually more successful at war fighting. Their larger material power means they tend to conquer weak polity types, which provides incentives for state-building. On a system-wide level, states should expand in size and shrink in number, as those with high state capacity conquer and absorb those with weak state capacity.

Despite its historical richness, many scholars question whether the empirical record supports the bellicist viewpoint. The primary criticism is that Tilly cannot explain why many states form late in the historical process, or why many instances of state formation appear to happen in the absence of the pressures of war.Footnote 9 This paper points to two other central issues, one empirical and one theoretical. Empirically, bellicists believe states have advantages early in the process that lead them to outcompete rivals. Today, we find this view almost certainly incorrect. Not only did the stateless Vikings conquer the more “modern” English, but other kinds of polities consistently outcompeted emerging states in the earliest periods of state formation. Theoretically, the state-formation literature has also struggled to provide a clear account of its mechanisms. It presumes that states converge on an institutional form through a competition mechanism. But it does not specify how this convergence occurred. How did polities learn about the advantages of state-like reforms? How did they learn to practically implement the reforms? Concretely, how did this process play out?

Theories of Diffusion

One prominent alternative set of explanations for state formation revolves around social processes of diffusion. These theories point to learning and emulation as the processes by which rulers and political units converged on a set of state institutions. This is a prominent explanation for the diffusion of the nation-state, particularly for the period since the end of World War II.Footnote 10 Recent work, reviewed here, has extended similar norms-based arguments to earlier periods of state formation.

Grzymala-Busse and Huang and Kang argue that diffusion processes account for the early stages of state formation.Footnote 11 Grzymala-Busse shows that institutional practices and norms diffused to states over time as clergy migrated to different royal courts, and as Church institutions and resources were expropriated by rulers during the Reformation. Her theory of diffusion rectifies two problems in war-centric approaches: she explains why European states took on particular institutional forms (when many options were available), and why state formation came with seemingly nonfunctional aspects (state involvement in public morality and social discipline, for example). Huang and Kang offer a similar diffusion-oriented account of state formation in East Asia, showing that Japanese and Korean elites consciously and intentionally emulated Chinese models of governance for the sake of prestige and domestic legitimacy.Footnote 12 They also show that these institutions were adopted in the absence of war. The advantage of diffusion-based theories is that they have a clear understanding of the mechanisms by which states learn and innovate.

One central problem with the emerging literature on diffusion is it treats diffusion as an alternative to war. This work succeeds in showing that war is not necessary for the diffusion of ideas. However, this does not mean war plays no role. In fact, if war was a primary means through which societies interacted, then we should expect that warfare was a central means of diffusion. We build on this prior work to demonstrate the role of warfare in diffusion.

Linking War and Social Diffusion

We showed that prominent theories of state formation emphasize war and competition as key to state-building, while an emerging literature has identified how diffusion processes can contribute to state-building in the absence of warfare. We argue there is a heretofore unexplored connection between bellicist and sociological theories of diffusion: warfare can be a potent way that new governance technologies spread. War brought leaders into contact with one another, led to trade, and generated migratory flows; each of these sparked the diffusion of specific technologies of state-building.

Traditional theories of state formation often measure state formation by examining the rise of the territorial state. The central argument is that war generates pressure that leads to the creation of a territorial state. These theories focus on state formation as an outcome rather than a process (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Standard bellicist accounts

We disaggregate state formation into a set of associated political, economic, and military reforms. This is a method used by scholars who study diffusion. These reforms are conceptually separate. Programs designed to bring the economy under state control, for example, are separate from policies designed to extend judicial institutions into the periphery of a territory. By disaggregating reforms, one can provide a much richer story about state-building that fits with new work in history, economics, and law.

Focusing on the reforms—the process of state formation—has several advantages. First, states did not suddenly form in the early modern period. Whereas classical scholarship on state formation concentrates on the period after 1500, when the modern state began to appear in its fullest form, modern historians and political scientists emphasize a continual process of reform that generated the modern state. The early states arising out of the medieval period adopted the reforms that built modern states at different tempos and in different ways. By disaggregating state formation into sets of reforms, we can concentrate on determining the timing and cause of each set.

More importantly, concentrating on reforms avoids selection biases inherent in studying outcomes. Communities that began state-building processes can be selected out of the system by conquest. A variety of exogenous factors contributed to the demise of even very modern states (by historical standards), including geography, weak rulers, and natural disasters or other events. This paper features an important example. The most modern state at the close of the ninth century, Alfred's Wessex Kingdom, had a standing army and fortifications, a strong economy, a well-unified legal system, and an impressive record of geographic expansion, but within two centuries it was conquered by Denmark, which lacked these state-like reforms. By treating state-formation processes as the dependent variable, we avoid selection biases in state formation by concentrating on techniques of state-building.

We focus on three sets of state-like reforms: military, economic, and legal. Military innovations connected to state-building are those that reduce the costs associated with defending territory, such as fielding a standing army or navy, and providing fortifications during peacetime to reduce internal and external threats. Economic reforms are intended to increase the economic capacity of the central state, such as by raising taxes, minting coins, or developing the region's economic or trade capacity. Legal reforms either create a national unification of laws to enhance central power or deepen the connection of a central power to the administration of a region through regional laws. To be clear, the specific innovation varies. Even today, different states have different strategies for policing and taxation. But an innovation counts as connected to state formation if its intent is to enhance central power.

War, Diffusion, and State Formation

The crucial difference between a traditional bellicist theory and our own account is the mechanism. Traditional bellicist accounts are Darwinian in emphasis: the strong survive, and the weak must emulate or be absorbed. The losers should emulate the winners. By contrast, our account emphasizes the noncompetitive elements of war. If the diffusion of ideas follows a social logic, then exposure to new ideas stimulates advancement. Successful warring states, which go abroad, war, and conquer, should modernize during or after fighting, because war making leads to substantial contact with other communities, promoting learning. In this view, the winners can also emulate the losers. Here we lay out this latter view.

How War Leads to Diffusion of Reform

Why do political communities innovate in ways that enhance state formation? Earlier we showed that state formation is a set of technologies that need to be learned. The traditional view of scholars of state formation posits a competition mechanism to explain learning and adaptation. Losers (or potential losers) emulate winners in the effort to compete against them. The state best able to modernize is the one most likely to survive, as it can muster more economic resources and field a stronger army. Now we present a bellicist diffusion mechanism of learning, emphasizing how war produces opportunities for learning through interaction rather than competition.

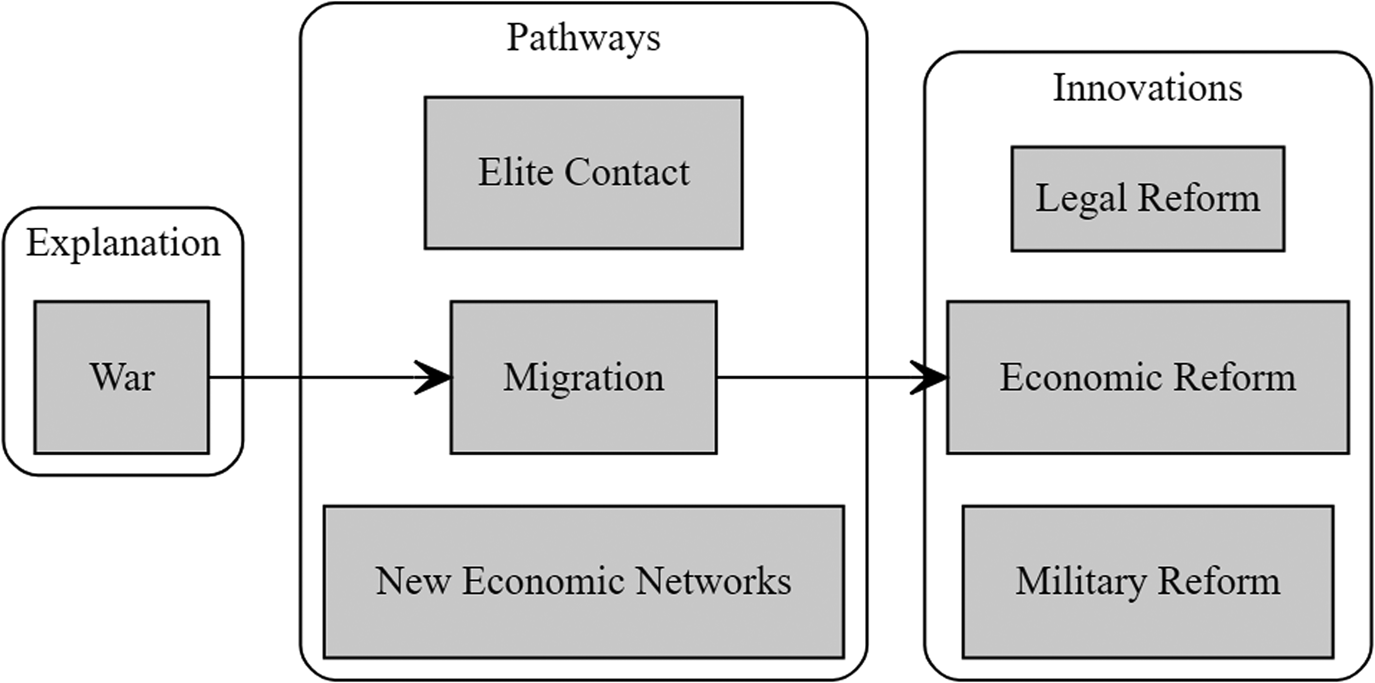

The central intuition here is that war disrupts societies and generates interactions across borders. It is inherently disruptive. War brings societies into direct contact and disrupts traditional social, economic, and political structures. Building on recent scholarship about international policy diffusion, we show how the consequences of war—the creation of new social networks—generate opportunities for learning across borders. In so doing, we focus on three pathways to diffusion: elite contact, migration, and the formation of new economic networks (Figure 2). For each pathway, war initiates a process that makes the diffusion of ideas conducive to state formation more likely.

Figure 2. Bellicist theory of diffusion

One way war generates diffusion is by putting political elites in contact, encouraging learning. Political scientists often describe elite learning as an important element in policy diffusion. Political elites look to neighbors to identify model policies and learn of their effects.Footnote 13 In the medieval period, war provided an opportunity for such learning. Political elites traveled with their armies. They had opportunities to observe and learn about the military, economic, and political systems in different areas, creating opportunities for what Michael Horowitz calls “demonstration points” for innovations.Footnote 14 For example, a ruler could directly observe fortifications, minting operations, and other physical features of rising statecraft, learning about the role and function of new technology. Furthermore, on successful conquest, the new ruler would inherit the bureaucracy of the deposed kingdom and learn how it extracted wealth, commanded loyalty, and raised armies. To be clear, this was not the only pathway to elites’ learning from one another; some future kings were raised in foreign courts, and some political elites would travel abroad and return home after acting as mercenaries. Yet war was perhaps the most common means by which elites learned about others’ policies in intimate ways.

A second way war encouraged diffusion and innovation was by encouraging migration. As is familiar to contemporary scholarship, war often leads to mass migration as people flee violence or are forcibly displaced. These episodes of migration can contribute to the diffusion of ideas as migrants take ideas or technologies with them across borders. A vast body of literature documents how waves of migrants and refugees have contributed to innovation and the diffusion of technology across borders.Footnote 15 Early studies of technology, for example, linked mass migration away from political violence to the diffusion of industries across Europe, such as glass-blowing and textiles.Footnote 16 Moreover, and more relevant to the cases that follow, successful conquest can lead to planned and controlled migrations of skilled personnel across borders. Tradespeople and individuals with administrative know-how were somewhat rare and valued during the period. When one political unit conquered another, it often exported skills and knowledge back home by encouraging or coercing individuals to return to their home kingdom. This migration spreads technical knowledge useful to rulers. Warfare can also lead individuals to settle in foreign lands, spreading technology abroad. Studies in the archaeology of the classical world, for example, show that occupation of new lands led settlers to spread their native technology abroad.Footnote 17 This was especially common in Northern Europe, where many Vikings spread into areas such as Normandy and the Danelaw in England, developing new homes in foreign kingdoms; this likely exposed Scandinavians to English technology, laws, and social practices.Footnote 18

The third way war encourages diffusion is through the development of economic ties.Footnote 19 Economic networks may be reshaped because of political and social change. Political elites might establish new towns or emporia with the explicit aim of creating new trade hubs, or bases for further military raids (Dublin is an example).Footnote 20 The goal was likely to seek rents, but one unintended effect may have been a new source of technology diffusion across borders. In addition, people who resettled in new lands may have created trade networks with their homeland, fostering new trade ties. While trade may have been a source of diffusion of ideas across borders, this is difficult to trace empirically due to evidentiary limitations in the cases that follow because trade network data are sparse and uncertain. We therefore do not focus on it in the empirical sections.

In sum, war encourages diffusion. Political elites in medieval Europe likely paid close attention to the specific techniques of rule used by foreign elites. War was not the only pathway to the diffusion of ideas—universities, the Church, and other relationships also likely promoted diffusion—but it was an important source of ideas. Conquering states could exploit the institutional innovations and entrepreneurs in the states they conquered, exporting them back home.

Research Design

Why do political communities adopt new techniques, technologies, and administrative devices to enhance state power? We focus on the case of Nordic states from the dawn of the Viking Age to the end of the High Middle Ages (CE 800–1300). We do so for two reasons. First, Nordic state formation is an important case in Tilly's bellicist theory of state formation. They are “most-likely” cases for Tilly's theory, as all three states that centralized did so in the face of intense warring; the one that did not centralize faced primarily internal threats.Footnote 21 Perhaps for this reason, Tilly suggests the Kalmar Union, the unification of the Nordic states in 1397, as the first instance of state formation in the Nordic region.Footnote 22 He pays little attention, however, to the centuries of Scandinavian centralization that preceded it. Understanding and explaining these initial origins of the formation of early states are critical to understanding broader processes of diffusion.

Second, using four cases—Denmark, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden—is appropriate for a most-similar research design. By the end of the thirteenth century, there was clear variation on the dependent variable, despite initial similarities at the start of the period. Denmark and Norway had undertaken significant processes of centralization, creating strong monarchies. Iceland, however, remained less centralized, providing variation on the dependent variable. Sweden also produces variation because it was substantially slower than Denmark and Norway in developing state-like institutions; Sweden started to develop such institutions largely after the Viking period. The clear variation on the dependent variable avoids problems associated with selecting on the dependent variable, which is common in studies of state formation.Footnote 23

Despite the differences in outcome, the four regions had factors in common. Their similar cultural and historical legacies led to commonalities in pre-Viking legal, organizational, and military policies. They generally lacked urban communities, had similar local legal processes, and had contact with Rome and the Church. These factors provide an ideal environment to understand why diffusion occurred in some areas, such as Denmark, but not in others, such as Iceland.

The central explanation is that war promoted the diffusion of reform.Footnote 24 The question is whether this occurred via a mechanism of competition or a mechanism of diffusion. We treat these as two differing explanations for the connection between war and state formation.

We do not test other common alternative explanations due to their limited explanatory power in this period. For example, one emerging explanation for state formation is the absence of towns, as towns and cities often resisted incorporation. This may be partly true—Scandinavia did lack large cities—and therefore it may be a permissive condition. But it is insufficient to explain the differing Scandinavian patterns because all four states lacked cities but only two entered rapid state-formation processes.

We rely on process tracing to identify clear differences in the observable implications of the diffusion and bellicist explanations.Footnote 26 Traditional international relations scholarship on policy diffusion often debates which mechanism is most important. There is insufficient evidence to identify which mattered the most in the period we are studying. However, sufficient evidence shows that each of them was important for different instances of diffusion (Table 1).

Table 1. Observable implications of the two hypotheses

The first question is whether war preceded periods of innovation by Scandinavian countries. To find out, we compare Denmark and Norway in the Viking period to Iceland and Sweden in the same period. We find that periods of innovation quickly followed successful Viking raiding and warring. This shows that war likely had some positive role in institutional innovation.

The primary way to easily discriminate between the diffusion and bellicist explanations is to identify who is learning and who they are learning from. If the technology was first adopted by winners and then emulated by losers, then the evidence is consistent with the bellicist explanation. If the winners emulate the losers, then it is more consistent with the diffusion explanation. After war, the political elites of the conquering community export the knowledge of statecraft, learned from the conquered, back home. This leads to a diffusion of knowledge, making the winners more state-like.

The process-tracing evidence reveals how elite learning and migration diffused knowledge between the conquered and the conqueror. We focus on military, economic, and legal innovations, describing a series of steps taken by Scandinavian powers to modernize statecraft during the period. We then identify how and when the Scandinavian powers learned this statecraft. For example, we check whether there is direct evidence that migration was encouraged in an effort to create administrative capacities within the home state, whether written records describe stays in foreign courts that were or could be sites of learning, and whether the practices developed in Scandinavian kingdoms clearly emulated the practices in the places they conquered. By doing so, we show that the knowledge that enhanced state formation in some Scandinavian states had diffused from the states they raided and conquered.

One potential threat to our argument is the role of Christianity. While we focus on how war produced diffusion, other work also credits Church agents as bridges between societies that diffused administrative know-how. This may pose a problem for our argument because the mechanisms—especially the role of elite travel—are similar. Scholars who specialize in Scandinavia's Christianization focus on political elites’ travels abroad, such as the missions undertaken by Harald Bluetooth (Denmark) or Olav Tryggvason and Olav Haraldsson (Norway), as the moment of interaction that generated diffusion.Footnote 27 We view these as largely complementary arguments, insofar as they also point to the role of diffusion.Footnote 28 However, the case study material focuses on a specific set of military, economic, and legal reforms. In each section, we emphasize the role of warfare in prompting these specific reforms—and in doing so, we show that war, and not religious actors, promoted reform. However, in making this argument, we do not exclude the possibility that other diffusion mechanisms later produced other reforms (when applicable, we note in the case study material instances in which clerical agents produced reforms).

For the process tracing, we rely primarily on secondary sources. A key limitation of the historical record is that we are discussing the period often known as the Dark Ages due to the lack of written records. There are contemporary written records,Footnote 29 but they are often unreliable or ideological.Footnote 30 This paper thus relies on modern scholarship, which emphasizes archaeological evidence such as coins, jewelry, fortresses, and other artifacts. This evidence is almost tailor-made for our purposes, as it enables us to identify whether designs diffused across space and what prototypes they emulated.

State Formation in Northern Europe

Here we describe state formation in Northern Europe in CE 800–1300. During this period, two states engaged in substantial modernization: Denmark and Norway. We describe how military, economic, and legal reforms led to substantial power. We demonstrate that the successful Viking raids, especially in England, led to the diffusion of English governance and military technologies, prompting state formation. By contrast, two other states—Iceland and Sweden—did not form state-like institutions. Iceland was largely isolated, preventing the diffusion of ideas. Sweden was oriented east, toward the Baltics, and therefore its international affairs did not provide as many opportunities to learn about state formation as were presented to Denmark and Norway, which were oriented west, toward England and Western Europe.

Military Reform

Before the successful Viking raids and conquests in England, there were few indications of state centralization in military affairs in Northern Europe. Prior to the late tenth century, there is no evidence of standing armies in Northern Europe and limited evidence of complex fortifications. However, after successful Viking raids and conquests abroad, military reforms prompted centralization in Denmark and Norway. In sum, revolutions in Danish and Norwegian military affairs appear linked to the diffusion of ideas from the conquered to the conquerors.

Two key revolutions in military affairs in the tenth and eleventh centuries contributed to state formation: the construction of a network of fortresses in Denmark and the formation of standing armies. These were linked. The formation of standing armies is considered a key component of state formation.Footnote 31 Standing armies reflect a centralization of power and a monopoly on violence within rulers’ territory. They indicate greater ability to tax and coerce. Fortresses played the same role, serving as a means of internal and external control.Footnote 32 Ring fortresses allowed local populations to gather within the fortress walls when faced with enemies. Thus fortresses made plunder and conquest harder and less profitable.Footnote 33 The effectiveness of fortresses depended on the dispatching of standing armies to fortresses under siege. The nature of the fortress system under Harald Bluetooth is suggestive of the presence of early forms of standing armies.Footnote 34

Before successful Viking raiding abroad, Denmark and Norway had no standing armies and limited fortress building. Before they raided, settled, and conquered England and mainland Europe, Scandinavian armies were seasonal war bands and mercenaries that lacked formal structure and permanence; they were not standing armies.Footnote 35 Scandinavian states also lacked a sustainable program of fortress building and maintenance. Fortresses had existed in Scandinavia, but they were rare, simple, and not incorporated into Scandinavian styles of fighting.Footnote 36 Denmark was, in sum, “unfortified” prior to the construction of these ring fortresses.Footnote 37

After successful wars abroad, Denmark began to develop state-like military innovations. Recent archeological work has discovered complex ring fortresses in Denmark dated to the late tenth century, during the reign of Harald Bluetooth. Scandinavian historians have now begun to characterize these fortresses as significant elements in Scandinavian state formation.Footnote 38 Their construction and maintenance required technical and organizational skills.Footnote 39 They were likely capital-intensive and required standing forces to occupy them.Footnote 40

Historians and archeologists emphasize the role of diffusion in Scandinavian military reform. These Danish fortresses emulated similar fortifications erected in England, the Low Countries, northern France, Lower Saxony, and Holsten to guard against Viking raids.Footnote 41 The fortresses were particularly prominent in England as part of a defense network that Viking raiders encountered, leading scholars to suggest that the English fortresses were the main inspiration behind Harald Bluetooth's fortresses.Footnote 42 Harald himself would have encountered these structures in raids on English territory.

England, especially Wessex, was the most likely model. King Alfred had erected a system of fortresses (burhs), created standing armies at the burhs, and established a naval force.Footnote 43 Alfred's successors continued to have a standing army and expanded the navy.Footnote 44 During the ninth and tenth centuries, Viking raiders pillaged, settled, and conquered parts of England; they also made alliances with and obtained tributes from rulers in England.Footnote 45 As a consequence, Danish and Norwegian raiders were intimately familiar with English defenses and governance structures from an early date.

Innovations in naval military systems also likely diffused from the losers to the winners. There are indications that Danish and Norwegian kings implemented English systems for organizing their navies. The reigns of Harald Bluetooth's successors Sweyn Forkbeard and Cnut the Great show evidence of a standing elite military force tied to the royal throne in Denmark.Footnote 46 As Danish rulers of England, they relied on the English lithsmen navy that was introduced by King Æthelred of England in 1012.Footnote 47 The lithsmen were a permanent fleet, mostly manned by Scandinavian warriors. Once Cnut conquered England, becoming its king, he expanded the tax introduced by Æthelred to finance the activities of this permanent fleet.Footnote 48 Norway follows a similar trajectory. Haakon I likely introduced the naval leiðangr system.Footnote 49 This was a conscription system for local and national defense. Haakon I was raised in the English court under Æthelstan (as part of an agreement with Haakon's father, King Harald Fairhair of Norway). The naval system Haakon I implemented bears similarities to what was in place during Æthelstan's reign, which lends strong support for a theory of diffusion.Footnote 50

The competition hypothesis cannot account for these modernizations. If the competition hypothesis is correct, we would expect to see military innovations in Denmark when it is threatened by states that have large armies and rely on fortifications. The key period in which Denmark was threatened was during the ninth century, when the Carolingian Empire under Charlemagne menaced Denmark. Yet there is no evidence of any military innovations at that time. Instead, innovation followed the successful wars abroad. On balance, the chronology and the circumstances behind the adoption of different military reforms are far more consistent with the diffusion hypothesis.

Economic Reform

Before the Viking conquest of England, the role of the state in economic affairs was limited in Scandinavia. During most of the late first millennium, silver was largely used as part of a display economy. In the ninth and tenth centuries, when Viking raids into England were common, Scandinavian states began to strengthen and modernize their control over the economy. The most remarkable evidence comes from the growing number of national and regional mints in Denmark and Norway.Footnote 51

The introduction of measures to control the monetary supply was important for state formation. Early modern political theorists emphasized the control of the economy, especially coinage, as a crucial element of sovereignty; controlling the money supply meant controlling economic affairs.Footnote 52 More specific to Northern Europe, scholars agree that minting currency was central to state-building. First, national mints provided an early source of state revenue. Kings could debase a currency in moments of crisis as a source of revenue, sell the right to mint to local moneyers, or collect fees for reminting coins.Footnote 53 Economists today recognize this as a historically important tax in the medieval context.Footnote 54 Second, coins provided symbols of state power when literacy was rare. Viking kings often included their own images or names on coins to demonstrate their authority. Finally, kings could use minting policies to stimulate the growth of trade and towns to enhance their power.Footnote 55 In Northern Europe, recoinage and taxation went hand in hand.Footnote 56

There is substantial evidence that Viking conquests of England stimulated minting in Denmark and Norway, pointing to diffusion as the most likely pathway. Before Viking successes in England, minting was relatively rare outside of one or two trading towns.Footnote 57 After Viking successes, large numbers of mints flourished during the reigns of Harald Bluetooth, Cnut, and Cnut's son. Direct archaeological evidence supports this link. The evidence is most pronounced in Denmark. Coins developed in the eleventh century usually used English motifs, and some were clearly based on earlier English designs. In addition, there is significant evidence that the first moneyers who expanded minting on behalf of Cnut within Denmark were English, likely brought back to Denmark for their skill in creating coins.Footnote 58 Similar evidence is found outside Northern Europe, in areas where Viking rulers saw success. The Viking founders of Normandy, for example, adopted Frankish systems of coinage as part of their revenue policies to generate a strong state after wresting control of Normandy from the remnants of the Carolingian Empire.Footnote 59 Norway is a more interesting case. Unlike the Danish rulers, Norway's ruler did not travel to England. Instead, Norway's King Harald traveled extensively, spending eight years in the Byzantine Empire. He introduced coinage on his return. Svein Harald Gullbekk credits the innovations to Harald's return with “new ideas” from his travels abroad.Footnote 60

There is overwhelming evidence against the hypothesis that military competition led to the formation of mints. First, the Vikings clearly emulated the weaker power. Cnut, who increased regional mints, was sitting on the English throne when he expanded Danish mints. Second, the timing is inconsistent. If threats from a strong military power forced the Danish to emulate a more powerful rival, then they should have adopted Carolingian minting practices a century earlier. Charlemagne's empire consistently menaced Denmark during that period; yet the Danish did not adopt the currency technologies used by Charlemagne. On balance, significant archaeological evidence links the diffusion of craftsmen and knowledge to the growth of Northern European mints, but there is no evidence—even circumstantial—to link the growth of mints to military competition. There is no evidence, for example, that Viking armies required locally minted coin to secure the service of soldiers or to build and enhance fortifications.

In sum, the growth of regional and national currencies in Northern Europe was related to the diffusion of ideas. The growth of mints was associated with wealth and political power in England and elsewhere. When exposed to this technology of state-building, Northern European leaders adopted it. They sent craftsmen to their lands, expanded the mints, and used them to obtain revenue and legitimacy.

Legal Reform

Unlike growing royal control over the economy and military modernization, legal reform during this period is difficult to study. It was the Dark Ages, and legal reforms leave few identifiable structures, like money and fortresses, that can be discovered by archaeologists. Therefore, empirical claims about the period must be cautious and tentative. Yet there is significant evidence the Viking invasions brought back legal knowledge to Scandinavia that led to substantial political and legal reforms that enhanced state-building.

Legal reform, and the codification of laws, are essential elements of state-building. Scholars of the period stress that law codes created unity, expressed royalist and statist ideologies, and enhanced state power.Footnote 61 Codification of laws also typically included state-backed bans on private forms of violence within the state.Footnote 62 Max Weber's claim that the state holds a “monopoly on the legitimate use of physical force” is premised on the existence of legal institutions that can be relied on to pursue redress in lieu of private violence.Footnote 63 Finally, the development of an administrative apparatus—a judicial system and a system of police, or some other public law enforcement mechanism—is important to give force to laws.Footnote 64 The designation of administrators to manage local affairs is also a sign that the state is moving beyond the king and his immediate advisers to a more complex and comprehensive entity that can administer power.

The Viking attacks and other relations with England exposed Danish leaders to a vibrant English legal culture. The tenth- and eleventh-century English state was the most centralized state in Europe at the time; as Paul Hyams notes, it had “the state-like characteristics now identified by scholars.”Footnote 65 Much of this centralized state was based on English law codes, which created a system of public justice and defined the relationship between the Crown and smaller political subunits within England. There is clear evidence Scandinavians soaked in the legal culture.

There was a clear transmission of English legal concepts into Norway, which was an early adopter of English legal norms. Scholars of the period describe how Norwegian kingship and laws closely tracked an English model, using English loan words and concepts in developing royal power and legislative authority. Peter Sawyer argues that this was due to the diffusion of ideas, including contact between Viking-age merchants and embassies.Footnote 66 The most direct evidence for how this diffusion occurred comes from the period around 1035 when Cnut's son, Sweyn, ruled Norway along with his English wife Ælfgifu. They imposed laws that levied heavy taxes. Historians have detected a clear process of legal diffusion. The legal terms and measures for the taxes—hearths, pinches, and bundles—are English in origin. The aim was state-building—to create a foundation for Danish power in the territory. As Miriam Tveit explains, “Cnut tried to impose a mode of taxation working on the European continent and in England onto the Norwegian realm … Legislation and taxation would consolidate the power of the northern kingdom.”Footnote 67

The evidence of legal diffusion in Denmark is more difficult to study, but the historical record points to possible transmission from England to Denmark. After Sweyn's conquest, Viking leaders were exposed to and extensively engaged with English legal institutions when Cnut gained an administratively complex state governed by laws.Footnote 68 Not only did he administer the laws, but he and his advisers also developed two well-known English law codes and appear to have used them as a political strategy to enhance power.Footnote 69 Cnut's use of English laws was part of a larger historical process: Danish embrace of English laws was not novel. The Danish who settled in England in the ninth and tenth centuries, in the region later known as the Danelaw, formed an integrated community with the English in the region and obeyed both English law and regional laws they themselves devised.Footnote 70 This provides evidence not only of exposure to English legal practices, but also of sustained engagement with them.

There is also circumstantial evidence that Danish rulers imported some of these concepts into Denmark. Cnut brought at least some of the legal machinery from England home. Timothy Bolton, inferring from English settlement patterns in Denmark, concludes that Cnut likely brought town-reeves to Denmark.Footnote 71 Reeves were royal officials who enforced the law by carrying out sentences or hearing cases. It is an essential administrative office for the state to replace private with public law enforcement.Footnote 72 In sum, during the early stages of Scandinavian law, innovations from England spread when people familiar with English practices returned home. Sharp limitations to the historical record prevent us from evaluating the extent of these changes; however, a better-than-circumstantial case can be made that the written record left to us is suggestive of early legal innovation owing to learning from conquered territories.

The primary alternative explanation for the development of national legal institutions is the influence of other European law codes. This debate points to a broader context and merits discussion. Thus far, our theory has been that the diffusion of knowledge, rather than competition, was the primary source of state formation in Europe. The specific mechanism we focus on is war as an instance of diffusion. In the historical legal literature, however, diffusion is taken for granted. Scholars look to the period between about 1150 and 1250 as the “juridical century,” when legal codes were commonly adopted across large parts of Europe.Footnote 73 The focus on national law codes in this literature points to a later date for continued legal developments in Scandinavia. This alternative explanation does not compete with our own. Our central argument is not that war was the only means of diffusion but that war was primarily important for state-building as one source of diffusion. Our argument would be falsified if the Northern European states adopted law codes to enhance power and deal with rival external threats. But there is no evidence of that.

In sum, there is significant evidence that diffusion, not competition, stimulated legal developments in Northern Europe that were important for state-building. First, there is clear evidence that Cnut learned the English legal culture and imported at least its administrative offices back into Denmark. Second, when Cnut conquered Norway, he created national laws in that country that reflected the legal traditions he had learned in England. Finally, alternative explanations proffered by legal historians and historians of the region, while focusing on a different period, emphasize the diffusion mechanism in a way that complements the main theoretical claims of this paper. Learning, not competition, was central to legal state formation.

The Negative Cases of Sweden and Iceland

In the prior section, we showed that successful Viking wars abroad led to the diffusion of knowledge associated with state-building in Denmark and Norway. Now we explore two cases where state formation did not occur: Iceland and Sweden. Swedish state formation occurred considerably later than in Denmark and Norway, and Iceland did not undergo state formation before it was absorbed into the Norwegian kingdom in the thirteenth century.

This variation is puzzling given the considerable similarities between the four cases. As described earlier, before the Viking period, these communities shared a common set of patterns that makes them most similar yet their patterns of state formation diverge sharply. The reason for this divergence is that neither Iceland nor Sweden engaged in substantial raiding of other communities with state-like institutions. Iceland never engaged in substantial raiding abroad and was largely isolated. Sweden engaged in trade more than war, and was oriented east, toward Baltic communities that did not have state-like institutions.

Iceland

Iceland had the weakest state-like institutions. Iceland was settled in 874–930. From the establishment of the Icelandic Commonwealth in 930, it would remain a stateless society until it fell under the control of the Norwegian Kingdom in the thirteenth century.

In the Icelandic Commonwealth, power was dispersed across numerous goðar (chieftains). The chieftains regularly came together at the Althing assembly to establish common judicial and administrative functions, but at no point were state-like institutions or practices adopted. There was a legalistic culture whereby chieftains settled their disputes through arbitrations in the Althing, but these arbitrations did not involve an executive authority and are therefore dissimilar to the national law codes adopted elsewhere in Europe (where the state was taking on the role of enforcer of laws).Footnote 74 It is also far from clear that Iceland had a unified legal system. Jón Viðar Sigurðsson writes that it was “probably possible for chieftains to change and even make laws in their own chieftaincies.”Footnote 75 The chieftainships appear to have been more like tribes and clans than kings and states. These chieftains did not wield territorial power, but exercised power on the authority of their followers.Footnote 76 Their power was tied in large part to informal and personal relationships, rather than formal institutional relationships and hierarchies.Footnote 77

The technologies of state formation described earlier were not present in Iceland. There was no minting of coins because trade was conducted through barter.Footnote 78 There were also no standing armies. Rather, chieftains organized military forces on an ad hoc basis during periods of civil strife. At times, political life in the Icelandic Commonwealth was considerably stable and functional.Footnote 79 Iceland did see some consolidation of chieftainships by the late twelfth century, but nothing approximating unification.Footnote 80 It remained a “stateless” society.

Iceland presents a challenge to some bellicist theories. It did not engage in substantial challenges to neighbors abroad, but was often the target of attack. One might therefore expect Iceland to have adopted the state-like institutions of its neighbors in the British Isles and Northern Europe, particularly during periods when the Norwegian kings were interfering in Icelandic affairs and provoking civil strife. Yet there are no indications of the creation of state-like institutions or a consolidation of power into anything approximating a state.

Consistent with our argument, Iceland's opportunities to absorb institutional innovations from its neighbors were limited. First, although Iceland had relatively close ties with other Nordic kingdoms in the immediate aftermath of settlement, there was a gradual disconnecting over time.Footnote 81 In practice, this meant less migration and fewer opportunities for institutional absorption. Second, when Iceland Christianized (around CE 1000, due to pressure from the Norwegian king), it adopted the content of Christianity but not the institutions of the Church. Church matters in Iceland were firmly controlled by native political elites, limiting clerical influence.Footnote 82 Consistent with our expectations, state formation did not occur, as there were few significant opportunities for diffusion.

Sweden

Sweden seems to be a deviant case. The country did engage in trade and raiding, but it did not develop the institutions characteristic of Denmark and Norway. While Sweden was not isolated, like Iceland it was oriented toward the east, engaging in trade and war with communities that did not have strong state-like features. Sweden did not absorb state-like institutions because it had little interaction with state-like entities.

State formation in the areas of modern-day Sweden occurred much later than in Denmark and Norway. There is general agreement among scholars that Swedish state formation was considerably delayed, relative to the Danish and Norwegian kingdoms. Scholars generally see early key processes in Swedish state formation occurring in the twelfth century.Footnote 83

Sweden's institutions were weak or absent, compared to those of Denmark and Norway. Prior to the twelfth century, Sweden was characterized by numerous petty kingdoms and weak state institutions.Footnote 84 Compared to Denmark and Norway, Sweden was late in developing an ecclesiastical ideology of kingship,Footnote 85 developing succession rules,Footnote 86 and adopting unified national laws.Footnote 87 There is no evidence for codified laws prior to the thirteenth century.Footnote 88 It is only in the twelfth century that scholars have found a royal right to taxation and the first evidence of a written royal administration.Footnote 89 In terms of military changes, evidence indicates that the Swedish king had control over a standing ledung naval force in the thirteenth century, but the date is disputed.Footnote 90 The dating and nature of a military levy are also disputed.Footnote 91 In terms of economic transformation, Sweden briefly minted coins at the end of the tenth century, discontinued the operation by the early eleventh century, and then resumed it in the twelfth century.Footnote 92 According to Sawyer and Sawyer, the coinage delay in Sweden “reflects the late unification of that kingdom and the weakness of its rulers.”Footnote 93

One reason Sweden was late in developing institutions is that it did not engage in conflict and conquest in areas with strong state institutions. Swedes interacted considerably with the non-Nordic world, but they primarily expanded eastward. As Kent writes, “Whereas many western Vikings pillaged and traded with the west, many Swedish Vikings did so in the east.”Footnote 94 Swedes expanded to Finland, Russia, Ukraine, and other parts of Eastern Europe, founding cities such as Novgorod and Kiev, as well as establishing the ancient Rus. Some of these activities involved Swedish kings, but most were conducted by chieftains and their followers.Footnote 95 The Swedish Vikings’ interactions with advanced states in the East (such as the Byzantine Empire and the Abbasid Caliphate) were primarily through commerce.Footnote 96

Sweden's late development of state-like institutions is a deviant case in the state-formation literature, but it is consistent with our theory. We argue that exposure to new ideas is a crucial element of state formation, and that war is a powerful way such exposure happens. This is not to deny that diffusion through other means is possible. For example, Sweden did ultimately adopt state-like institutions. Whether this occurred through secondary learning from Denmark and Norway, commercial networks in the East, or networks fostered by the Catholic Church is a subject for further study. What is clear is that the Swedes did not wage wars in areas with advanced state institutions, thus limiting one important pathway to state formation.

Mongols, Normans, Romans, and the Dutch

Early instances of state formation in Northern Europe occurred because war diffused statist reforms across borders. The Vikings’ successful wars led to elite learning, and to controlled migration of administratively skilled personnel, and provided demonstration points that contributed to state formation in Northern Europe, sparking a wave of statist reforms. Here we show the generalizability of this view to other parts of the record of state formation. We make two arguments. First, early in the record of state formation, war and conquest were common ways ideas about politics spread and diffused. Second, aspects of the diffusion mechanism are likely to be generalizable to more modern cases. In the conclusion we also explore broader links to emerging literatures on state formation in the modern period.

Until the modern period, one common way diverse polities came into contact was through war and conquest. In this sense, the Vikings were not special. Other major powers, such as the Persians, Romans, Mongols, and Huns, also came into contact with diverse polity types through expansion and war. If the bellicist literature is correct, then the weaker units should have emulated and adopted the political practices of stronger units; by contrast, if we are correct, strong units would also have emulated weak ones when they found a reform useful. The empirical record strongly supports our view. Conquering states frequently adopted political, economic, military, and social forms, appropriating ideas from those they conquered. For example, Genghis Khan's conquests revolutionized the Mongol Empire's approach to siege warfare, as his army acquired expertise from the Chinese and other civilizations he conquered.Footnote 97 After the conquest of Jerusalem, the Crusaders absorbed political and intellectual ideas from their enemies, sparking a European revolution in math, art, and intrigue.Footnote 98 The Normans, as they conquered Sicily and Southern Italy, adapted to their new holdings, absorbing and often maintaining the administrative apparatus of conquered territories.Footnote 99 These examples show that the strong often emulate the weak, and war promotes the diffusion of ideas.

There are also clear cases where the weak emulate the strong after war. Recall that our earlier argument focused on the Vikings for reasons related to research design; to discriminate between competition and learning, we emphasized cases where the strong emulated the weak. In pursuing generalization, however, it is important to also consider the broader category of cases, including instances where weak communities emulated strong states. Periods of imperial expansion, for example, saw war spread technology and administrative techniques. In Africa, the shape of modern polities and the systems of government in place were diffused during colonialism (albeit by coercion).Footnote 100 Similarly, in North America, American Indian polities appropriated imperial weapons, horses, monetary politics, and systems of diplomacy through a process scholars of the West have called “adaptation.”Footnote 101 Each of these major invasions of a people who had very different “fundamental institutions,” to borrow a phrase from Reus-Smit, likely triggered learning.Footnote 102

The second way this argument extends prior work is by providing a better account of the learning mechanism in paradigmatic cases for bellicist theories.Footnote 103 Bellicists often cite Tilly's work on the Italian Wars as central to their account of state formation. The central argument is that the wars occurred during a period in which state size and capacity rose concurrently with military size and capital requirements. It was this competition for resources and security that drove state formation. The problem, as described earlier, is that this does not provide a clear mechanism. How do states learn from one another?

Central to this learning process was the role of diffusion. Recent work shows that early periods of state formation in Europe saw political networks reshape fundamental aspects of political life.Footnote 104 The great powers emulated Dutch military reforms, sparking the military revolution that animates Tilly's account. Learning, not war, drove this process. Dutch leaders were classicists and experimented to reform the army on a Roman model. Their treatises were widely read.Footnote 105 These experiments became the basis for the reforms at the heart of Tilly's story, creating larger and more powerful armies.Footnote 106 Social networks were the key to diffusion. German princes—who had not experienced war for decades—had close personal ties to the Dutch, leading reformers to turn the Netherlands into the “military college of Europe.”Footnote 107 These reformers behaved in many ways like the clergy described by Grzymala-Busse, operating a nexus for the diffusion of military reform. The advantage of this focus on diffusion is that it establishes a clear causal connection between military needs and reformist outcomes by specifying how learning occurred. It also provides accounts of who learned, when they learned, and who was excluded from these networks.

Conclusion

Why did state formation occur in the Late Middle Ages? The dominant explanation in political science for European state formation is a bellicist account premised on competition. State-like political units outcompeted others; weaker units either adapted or were selected out of the system. In contrast, this paper proposes a diffusion-based mechanism by which war leads to the diffusion of reforms and policies. War leads to social interaction between belligerents, providing powerful opportunities for learning. Denmark and Norway successfully invaded and conquered more state-like societies. They brought home those reforms and in doing so reinvented their own polities. By contrast, Iceland remained isolated, and Sweden interacted with nonstate units; and they lagged in state formation. In making this argument, we have built on recent accounts of state formation in earlier periods. Rather than treating bellicist and diffusion-based explanations as different in kind, we see powerful ways they can be usefully combined.

By treating war as a means of diffusion, this paper situates the medieval steps toward state formation in a broader theoretical tradition. Modern scholars often argue that the surge in state formation following World War II and decolonization was in part the result of the diffusion of ideas. Powerful states and international organizations helped teach newly forming states how to be state-like, and encouraged and lobbied for reform.Footnote 108 This paper is part of an emerging tradition of scholarship that argues that this process of diffusion is not only a feature of post-World War II politics. It dates to the very first statist reforms in Europe. While the agents and circumstances of how diffusion works certainly differ across time, the process is the same. Communities come into contact and learn practical techniques for managing common problems. As the Icelandic proverb says, “Wisdom is welcome, wherever it comes from.”

Acknowledgments

We thank Alex Downes, Amoz Hor, and Jittip Mongkolnchaiarunya for helpful feedback on an early version of the paper, as well as the participants at the George Washington University ISCS Security Policy Workshop.