Published online by Cambridge University Press: 09 August 2005

A growing number of preferential trade agreements (PTAs) have come to play a significant role in governing state compliance with human rights. When they supply hard standards that tie material benefits of integration to compliance with human rights principles, PTAs are more effective than softer human rights agreements (HRAs) in changing repressive behaviors. PTAs improve members' human rights through coercion, by supplying the instruments and resources to change actors' incentives to promote reforms that would not otherwise be implemented. I develop three hypotheses: (1) state commitment to HRAs and (2) PTAs supplying soft human rights standards (not tied to market benefits) do not systematically produce improvement in human rights behaviors, while (3) state commitment to PTAs supplying hard human rights standards does often produce better practices. I draw on several cases to illustrate the processes of influence and test the argument on the experience of 177 states during the period 1972 to 2002.I would like to thank Mike Colaresi, Dan Drezner, David Lake, Lisa Martin, Walter Mattli, John Meyer, Mark Pollack, Erik Voeten, Jim Vreeland, and two anonymous reviewers for their detailed and thoughtful comments on various drafts of this manuscript, as well as the many other people who have helped me by asking hard questions along the way. I would also like to thank Michael Barnett, Charles Franklin, and Jon Pevehouse for advice during the dissertation research that supports this article, and Alexander H. Montgomery for assistance in data management. All faults are my own. For generous assistance in the collection of data, I thank the National Science Foundation (SES 2CDZ414 and SES 0135422), John Meyer, and Francisco Ramirez. For support during the writing of the article, I thank Nuffield College at Oxford University, and most importantly, Lynn Eden and Stanford's Center for International Security and Cooperation.

Human rights violations are pervasive.1

Last year, Amnesty International documented human rights abuses in 151 countries and territories. Amnesty International Report 2003.

See Rosati 2001; Lutz and Sikkink 2000; Risse, Ropp, and Sikkink 1999; Koh 1998; and Franck 1988. Hathaway 2002 argues that leading perspectives on international law assume that states intend to comply with their internal legal commitments. This assumption, commonly applied to HRAs, has been widespread among international lawyers and scholars but seldom tested.

Yet HRAs are no longer the only alternative for international regulation of domestic human rights policy. Few realize that the governance menu has recently expanded to include a growing number of formal institutions that embed human rights standards4

A standard is an acknowledged behavioral criterion established by authority, custom, or general consent as a model or example. See Merriam-Webster Unabridged online Dictionary, available at 〈http://www.m-w.com/cgr-bin/dictionary〉 accessed 6 may 2005.

I define PTAs in the broadest sense possible to include preferential trade instruments of many kinds, including unilateral preferential schemes, bilateral and regional agreements, and reciprocal and nonreciprocal agreements.

WTO members participating in PTAs are required to meet a set of preferential trading conditions defined in the text of GATT Article XXIV, Ad Article XXIV, and its updates, which include the 1994 Understanding on the Interpretation of Article XXIV of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, as well as the text of GATS Article V. Note that many PTAs are not notified to the WTO.

Abbott and Snidal 2000 identify variation in international legalization: hard laws are legally binding obligations that are precise and that delegate authority for interpreting and implementing the law; while soft laws are those that deviate from hard along several dimensions. The use of hard and soft law through the remainder of this article invokes Abbott and Snidal's attention to variation but simplifies by identifying one primary distinguishing characteristic: conditionality. Hard PTA standards establish enforceable conditions for integration, while soft standards appeal to voluntary principles of cooperation that do not require behavioral change to receive market access benefits. Abbott and Snidal 2000, 421.

My argument is a simple one about institutional design and influence. In the area of human rights, hard laws are essential: change in repressive behavior almost always requires legally binding obligations that are enforceable.9

This view stands in sharp contrast to the belief that coercion is unnecessary or counterproductive: that governments often conform to global human rights laws out of concern for legitimacy, even when laws are powerless to enforce compliance; and that coercion necessarily produces adverse consequences on the enjoyment of human rights. See Goodman and Jinks 2004; Johnston 2001; Payne 2001; Price 1998; Helfer and Slaughter 1997; Finnemore 1996; Koh 1996–97; Franck 1990; Henkin 1979; as well as Bossuyt 2000. For an exception, see Martin and Sikkink 1993.

First, most HRAs are not likely to effectively reduce violations most of the time. As I will elaborate in this article, HRAs are principally soft: they influence governments' human rights practices through persuasion rather than coercion, supplying weak obligations.10

HRAs, as with PTAs, vary in their degree of institutionalization, and exceptions to this claim are discussed in later sections of the article.

Second, PTAs are designed to enforce voluntary commitments to coordinate market policies at a transnational level. PTAs accordingly supply different mechanisms of influence, and they sometimes are designed to influence human rights. As I shall show, when PTAs supply soft human rights standards, they offer no capacity for coercive influence. Like HRAs, these agreements are at best designed to supply weak tools of persuasion and are unlikely to have any strong influence on government repression.

Third, when they implement hard standards, PTAs influence through coercion: they provide member governments with a mandate to protect certain human rights, while they supply the material benefits and institutional structures to reward and punish members' behavior. As I shall show, coercing repressive actors to change their behaviors requires a conditional supply of valuable goods wanted by target repressors. It does not require changing deeply held preferences for human rights and is likely to take place in a shorter time horizon. These agreements accordingly improve members' human rights by supplying the instruments and resources to change repressive actors' incentives to promote policy reforms that would not otherwise be implemented.

In the following sections, I elaborate this incentive-based theory of compliance with the principles of international human rights. At issue is the nature of institutional effects ex post of state membership in agreements that adopt various human rights standards, hard and soft. I seek to explain the consequences of PTA membership on states' human right behaviors and not the initial formation of the agreements.11

I nonetheless address the question of formation in some detail in the pages to come in order to consider the possibility that PTA influence is determined by self-selection.

For the better part of the past century, intellectuals from many disciplines argued that international laws are powerless rules that nations seldom obey and that cannot be readily enforced; and that international institutions are not likely themselves to influence the behavior of states.12

Today, most scholars of institutions take strong exceptions to these views.Some scholars view institutions as instruments created to overcome various collective action dilemmas to solve a variety of substantive problems.13

In this view, state defection from the rules is an ever present threat motivated by rational calculations of gains from unilateral action. Sustained compliance with institutions that challenge domestic preferences for behavior thus almost always requires some measure of coercion.14See Axelrod 1984; Keohane 1984; and Yarbrough and Yarbrough 1997.

Downs et al. 1996. This finding is nicely articulated in the case of human rights by Moravcsik 1995, who shows that European human rights regimes are likely to have little effect on those states that are not already disposed toward transformation, namely newly developing states.

This view has now come to stand in sharp contrast to the belief that “almost all nations observe almost all principles of international law and almost all of their obligations almost all of the time.”16

See Henkin 1979; and Koh 1996–97.

See Kratochwil 1989; Franck 1995; Finnemore 1996; and Meyer et al. 1997.

See note 9.

For the general argument, see Chayes and Chayes 1990, 1993, and 1998. For applications to human rights, see Goodman and Jinks 2004; Koh 1996–97; Franck 1990; and Henkin 1979. For applications to environmental policy, see Mitchell 1993; and Young 1994.

Human rights critics of economic sanctions, for example, contend that sanctions often fail to produce human rights compliance and, worse, cause further violations. See Rai and Eden 2001; and Helson and DeVecchi 2000.

This debate over institutional influence is at the foundation of the argument proposed here. As I argue, trade agreements are designed to solve a different set of problems than human rights agreements and supply different properties of influence. PTAs with hard standards can be more effective in influencing compliance with human rights principles than most HRAs; when PTAs supply coercive mechanisms of influence that HRAs lack, they tie compliance to substantial market benefits. Consider the logic of the argument in stages.

The problem of human rights compliance (see Figure 1)23

Figure 1 describes the percentage of all states in the world system reported to employ repression—through acts of political terror or by violating civil liberties—and that have ratified either the Convention on Torture or the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. All data are described in detail in the pages to follow.

Human rights behaviors: Percentage of states that repress and that ratify human rights agreements

A powerful constituency of states and advocates around the world hold strong and well-articulated preferences to make all states accountable for violations. They seek to influence repressive governments' behaviors to become compliant with rules protecting the inalienable rights of all people. International agreements governing human rights are accordingly charged with the difficult task of changing repressive governments' behaviors inside the sovereign territory of the state.24

There are two principal kinds of violators they must address.First, elites working in some repressive governments may hold preferences for human rights that they cannot self-enforce at home. This problem is perhaps most common to newly established democracies, where recently elected leaders are likely to have strong interests in consolidating human rights, while at the same time face substantial domestic opposition toward implementation, now and into the future.25

Second, other repressive governments may be ruled by decision makers with no identifiable incentives for human rights, or with strong incentives for repression. The vast literatures on repression suggest that elites ruling autocratic governments often gain substantial political and economic benefits from tyranny—benefits that range from a strong hold on political power to substantial economic wealth.26 Elites facing political competition by armed insurgent groups are also among the most likely to hold strong incentives for occasional to systematic use of repression to maintain political control, which is a highly valued good.If the problem to be solved is to sway an assortment of repressors to conform to international principles of human rights laws, the solution is to design international institutions with the capacity to influence elites operating under different domestic political situations to transform their behaviors.

It is well established in the theoretical literatures that international institutions can influence governments' human rights actions through two principal mechanisms: coercion and persuasion. As I have noted above, scholars of international organization and law disagree strongly about which form of influence should be the most effective. Although the majority of human rights scholars believe that coercion may be a useful tool of domestic policy influence, many remain optimistic that international institutions lacking coercive authority can nonetheless bring about compliance with law. I now turn to consider both mechanisms more carefully as they apply to human rights.

Persuasion is “the active, often strategic, inculcation of norms.”27

When they persuade, international institutions actively influence human rights by supplying targeted information to convince or teach repressive actors new ideas that are more consistent with the principles of international laws.28 Persuasion is a process of changing actors' preferences and understandings of appropriate social behavior to create new social facts.29See Ruggie 1998; and Payne 2001.

Coercion is “the threat or act by a sender government or governments to disrupt economic exchange with the target state, unless the target acquiesces to the articulated demand.”31

Drezner 2003, 643.

See Goodman and Jinks 2004; and Downs et al. 1996.

See Drezner 2003; and Eaton and Engers 1999.

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) concludes, for example, that the Generalized System of Preferences review process creates an independent and strong incentive for improving labor rights conditioned by the agreement, short of the imposition of sanctions. Recipient states have an economic stake in receiving a positive review, both to avoid sanctions, but also to encourage potential investment. See OECD 1996; and Cleveland 2001b.

There are four main reasons to expect that persuasion, alone, is unlikely to provide strong incentives to change most repressive actors' behaviors. First, persuasion requires changing actors' preferences for repression, and these preferences are likely to be highly valued. Repression is often used as a strategy to gain or maintain political power or to accumulate wealth or redistribute resources. In 2003 alone, Amnesty International documented dozens of instances where ruling elites employed acts of terror to maintain power and suppress opposition, including targeted killings of political challengers and terrorizing voters. Repressive opponents, such as armed insurgent groups, competing elites, or low-ranking members of the civil or military services, are also documented to use repression, extracting concessions and side payments from a wide range of targeted populations.35

In both cases, the gains from repression were likely to be highly valued and to be strongly preferred by the repressors. Strongly held preferences are likely to be harder to change than weakly held preferences.Second, when persuasion occurs it is likely to be a slow acting form of influence, taking place over a long-time horizon. To persuade, an institution must mobilize informed advocates to convince repressive actors that their currently held beliefs and habits are no longer appropriate. However, beliefs rarely change over night, but are often sticky. This “perseverance effect” has been confirmed in a wide variety of settings: individuals frequently adhere strongly to their beliefs even after new and better information has been presented.36

See Anderson 1989; and Slusher and Anderson 1996.

Third, persuaded actors may not be consistent across time. New leaders may come to power, and new opponent groups may form with preferences for repression. Successful persuasion of a government thus requires that each new repressive actor is persuaded to change their beliefs about the appropriateness of their behavior. Few repressive governments, however, are ruled consistently by the same elite or face the same set of repressive opponents for periods that are long enough to enact and achieve strong belief change. Leaders of repressive states are regularly overthrown or voted out of power, while domestic human rights opponents come and go.

Finally, persuasion requires repeated access to target repressors. Some repressive actors may be intimately involved in the decision-making processes of international institutions designed to influence human rights. Chief executives or their cabinet members and staff are among the most likely to participate in the repeated interactions organized through international institutions. Other repressive actors, however, are likely to be marginalized from participation in these institutions and remain isolated from active processes of norm inculcation. Armed insurgent groups contesting the government or vigilante civilians targeting ethnic minorities, for example, are not apt to be represented at the United Nations (UN) or to participate in the decision-making processes of most institutions.

Contrary to the belief that institutions can best influence without coercion, there are several reasons to expect that coercion is likely to provide stronger incentives against repression than persuasion under some conditions, and that coercion and persuasion may effectively influence human rights when they are supplied together. First, coercion is likely to be more effective than persuasion (alone) because it does not require changing actors' deeply held preferences for repression, but rather increases the costs of employing repression and the gains of adopting better human rights practices. A coerced actor can simultaneously hold preferences for human rights and choose to curb repressive behaviors in exchange for other forms of gains from international cooperation. They are likely to do so when those gains are more valuable than the benefits of repression. Reforms can be a side payment.

Second, coercion can take place in a much shorter time horizon than persuasion. If an institution supplies valuable goods under the condition that targeted repressors make human rights policy changes now or in the short term future, repressors are more likely to react in the short term to adopt new practices. Immanent sanctions on valuable goods provide strong incentives for reforms in the present rather than repressive behavior into the future.

Third, coercion can change a variety of different repressive actors' behaviors when they value the gains of cooperation more than the gains of repression. In fact, any domestic opponent to human rights with strong preferences for the goods achieved through cooperation can, under certain conditions, be coerced into supporting human rights reforms they would not otherwise select.38

These conditions require that benefits gained from adopting unwanted reforms are greater than costs of adoption; that no credible alternative supply of the goods are available without human rights conditions; and that target actors hold incentives for the goods achieved through integration. Also see Moravcsik 2000 for a similar argument in the European context.

For a discussion of hand tying through credible commitment, see Martin 1998 and 2000; Abbott and Snidal 2001; and Kahler and Lake 2003. I would like to thank an anonymous reviewers for helping me to clarify this point.

Fourth, coercion does not require direct and repeated access to target repressors. It only requires that target actors are informed of the coercion trade-off and value the benefits of international cooperation more than they value the gains from repression. No repeated institutional contact between the actors governing international institutions and the repressors they are trying to influence is, in principle, necessary. In practices, coercion and persuasion may take place simultaneously and are often compatible processes of influence.

In the preceding section, I have argued that the problem of human rights compliance is to influence repressive governments' domestic behaviors and that international institutions can influence human rights through two mechanisms. Although many scholars are optimistic that HRAs lacking hard standards are still capable of substantial influence on domestic policy, I argue the contrary: coercion is much more likely than persuasion (alone) to be effective. In the following section, I apply these claims to HRAs and PTAs, respectively, and develop three positive expectations about influencing human rights behaviors.

The international human rights regime is championed by a growing number of treaties and instruments designed to protect identifiable groups, such as women and children, as well as to protect all people against particular government behaviors, such as torture. At the heart of this regime are the UN Charter (Article 55) and seven international agreements that define a set of global regulations. Almost all states in the world have ratified one or more of these instruments.

This architecture of international law was principally constructed to influence through persuasion: to identify and classify which rights are globally legitimate, to provide a forum for the exchange of information regarding violations, and to sway governments and violators that laws protecting human rights are appropriate constraints on the nation-state that should be respected. Over the years, the regime has proven increasingly competent in supplying the instruments necessary to collect and exchange information on human rights violations, and to disseminate that information on a global scale.40

The major treaties furnish UN committees that formally provide a reporting and oversight function.

Despite this substantial capacity to classify and disseminate human rights norms and establish monitoring institutions, most agreements were not designed to influence through coercion, and those that were often fail to be effective: they remain quite soft.41

There is today only one major exception to this claim: the European human rights system supplies a unique set of instruments to enforce the Council of Europe's commitment to uphold HRAs. Almost all members have adopted the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms into national law, obligating national courts to enforce the agreement's provisions. The European Court of Human Rights is the superior arbitrator of disputes concerning noncompliance with human rights standards under the Convention, acting as a subsidiary to national enforcement in cases of failure. Europe, however, is exceptional. The vast majority of HRAs provide softer standards that are voluntary and weakly enforceable at best. See Cleveland 2001b. The Organization of American States (OAS) offers the closest comparison. The Commission monitors observance of treaty obligations for all states committed to the American Convention on Human Rights, while the Court monitors compliance under the Convention for states that have also recognized the compulsory jurisdiction of the Court. Yet OAS political bodies routinely fail to support or enforce the recommendations of the Commission or the judgments of the Court, and human rights standards remain effectively soft. See Dulitzky 1999; and Davidson 1997.

Small steps toward legal enforcement have only recently begun at the global level through the formation of the International Criminal Court (ICC), as well as at the regional level through courts such as the European and Inter-American Courts of Human Rights, and the state level through the two International Criminal Tribunals in the Former Yugoslavia and Rwanda. These institutions signal an important step toward management of human rights, but they nevertheless remain extremely limited in their jurisdiction and in their effectiveness to provide repressive states with the incentives to protect human rights.

See Cottier 2002; and Goodman and Jinks 2004.

There are therefore good reasons to be skeptical that most HRAs directly or frequently persuade repressive actors to change their human rights behaviors, especially among those who value repression highly. HRA's supply strong tools of moral suasion but offer few valuable incentives for repressors to change their beliefs about appropriate behaviors. They identify and lobby target individuals and groups, but they are often limited to accessing repressors that consent to be targeted to receive information. The exchange of information, once it begins, usually takes place over many months, if not years, and repressive actors inside the targeted state may well have changed during this time. What is more, there is no single HRA effectively able to punish perpetrators of even the most egregious violations of human rights.45

See Cleveland 2001a and 2001b.

The best case study evidence to date supports the argument. Risse and colleagues show that influence through persuasion depends crucially on the establishment of sustainable networks of advocates among domestic and transnational actors; that persuasion happens through several stages over time; and that the inculcation of new norms among the worst abusers often requires some coercive processes of instrumental bargaining, at least in the beginning.46

Because repressors value the gains from repression highly, they often use repressive acts to effectively outlaw or restrict domestic human rights mobilization.All told, HRAs rarely create the conditions necessary for state compliance with human rights because they are soft: persuasion, alone, is a weak mechanism of influence that does not supply strong enough incentives or commitment instruments to outweigh defection.

H1: State commitment to HRAs does not systematically produce improvement in human rights behaviors after commitment.47

It follows from the logic of the argument that the European case is a unique exception to the rule. Because various European human rights instruments provide harder standards than most HRAs, we should expect commitment to these instruments to produce more compliant behavior.

Trade liberalization is today regulated by multilateral institutions. At the heart of this system of liberalization is the 1947 General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs (GATT) and the WTO. This movement toward the globalization of trade has taken place in the context of regionalism, as a growing number of states commit to regulate trade through preferential agreements.48

For a discussion of the relationship between the world trade system and preferential trade, see Frankel, Stein, and Wei 1996; and Winters 1996. For a discussion of preferential trade statistics at the world level, see Grether and Olarreaga 1998.

PTAs were not principally designed to solve problems of human rights compliance. They are designed to resolve collective action dilemmas and internalize externalities that cross state borders. The instruments of preferential trade chiefly influence through coercion: they coordinate mutually beneficial rules of market access between states and limit defection through threats or acts to disrupt exchange with violating members. Not all PTAs are likely to supply the same degree of credible coercion; some may provide more valuable benefits and greater willingness to enforce the rules than others. All PTAs are nevertheless likely to supply some degree of valuable economic incentives (and thus the potential to change repressors' incentives to support human rights through threat to withdraw goods). Many supply mechanisms of persuasion coupled with coercion.

A growing number of PTAs provide member governments with a mandate to observe human rights (see Figure 2). These agreements fall into two main categories. In the first category are a great many PTAs that provide member governments with soft standards to manage their policy commitments (that is, agreement benefits are unconditional on member states' actions). PTAs do so by incorporating human rights principles and language into the trade contract, “affirming,” “recognizing,” or “declaring” member states' commitments to various human rights principles in the preamble of the contracts, or making reference to specific international human rights laws. The benefits of integration, however, are not conditional on the observation of these principles.

Preferential trade agreements with human rights standards

An example is useful, and there are many from which to choose. Article 6 of the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) Treaty articulates the “recognition, promotion and protection of human and people's rights in accordance with the provisions of the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights; accountability, economic justice and popular participation in development; [and] the recognition and observance of the rule of law”49

Article 6 (d), (e), (f), and (g).

These agreements supply similar human rights influence properties as most HRAs: a set of principled ideas legitimating appropriate and accepted behavior among a community of states. Because the standards are soft—agreement benefits are unconditional on human rights behaviors—this class of institution supplies no coercive mechanisms of influence. If these organizations influence human rights at all, they influence through persuasion, and one should now expect that they are unlikely to change most repressors human rights beliefs or practices.

H2: State commitment to PTAs supplying soft human rights standards does not systematically produce improvement in human rights behaviors after commitment.

Other PTAs provide member governments with “harder” institutional channels to manage and enforce their policy commitments (that is, benefits that are in some way conditional on member states' actions). These PTAs do so by placing the language of human rights in an enforceable incentive structure designed to provide members with the economic and political benefits of various forms of market access. These benefits are supplied under conditions of compliance with the protection of human rights principles or laws identified in the agreement. Behavioral change is a side payment for market gains, enforced through threat (direct or tacit) to disrupt integration or exchange unless a trade partner complies with their human rights commitments specified in the contract. A list of PTAs offering standards, hard or soft, is available in the Appendix 1.

The Lomé and Cotonou Agreements are strong examples of these types of PTAs. Cotonou provides the new institutional structure for the European Community's (EC) largest financial and political framework for cooperation, offering nonreciprocal trade benefits for certain African, Caribbean, and Pacific (ACP) states, including nearly unlimited entry to the EC market for a wide range of goods. The agreement, which replaced successive Lomé Agreements, commits “Parties [to] undertake to promote and protect all fundamental freedoms and human rights, be they civil and political, or economic, social and cultural”50

Articles 9, 13, and 26.

Lomé IV provided a similar hard standard in Article 366a.

This second category of agreement supplies coercion mechanisms of influence that most HRAs and all soft PTAs cannot supply. PTAs with hard standards can, under certain conditions, influence through coercion by changing repressive actors' costs and benefits of actualizing their preferences for repression. Consider again the abusive elite with strong preferences for repression. Where persuasion alone is likely to fail, hard standards can influence the problem of compliance without changing actors' preferences. They provide an economic motivation to promote human rights policy reforms that would not otherwise be implemented, and they do so in a relatively short time horizon. When institutionalized PTAs create new and valuable gains, hard agreements can also commit future elites with preferences for liberalization to human rights reforms they would not otherwise select. While influence through persuasion requires leveling a campaign to change a new leader's preferences for repression, influence through coercion requires only that the leader value the gains of integration more than the gains of repression. PTAs, moreover, may increase the costs of repression for any domestic actors that favor liberalization.

Hard PTAs are not a panacea for repression. They are likely to be much less effective in influencing armed opposition groups or governments under insurrection, where preferences for liberalization are low or absent among opponents. To be sure, not all leaders are likely to be influence by all agreements. Severely repressive elites that reap extensive benefits from repression that they value more than integration are apt to defect from agreements that offer only small gains or that require large-scale political upheaval. Moreover, target repressors that can secure an alternative supply of the goods achieved through cooperation without conditionality are likely to reject membership in PTAs that require human rights reforms. Exclusive of these conditions:

H3: State commitment to PTAs supplying hard human rights standards does systematically produce improvement in human rights behaviors after commitment.

The expectation that hard PTAs can influence repressive states to change their behaviors is open to the charge of endogeneity. It may well be the case that only states that protect human rights or that hold preferences to improve their human rights practices will join these agreements in the first place. It is thus crucial to establish whether states only join those PTAs that are consistent with their status quo behaviors. Do repressive states become members of hard PTAs, and how do these agreements influence them to change behavior after joining?

States increasingly create and join hard PTAs, and for the past twenty years, repressive governments have been among their many members. In 2002 nearly 30 percent of all states in the international system belonged to a hard agreement of some kind. Figure 3 shows that 40 percent of all agreement members were reported by Amnesty International to employ frequent acts of repression—political imprisonment, execution and other forms of political murder, detention without trial, and other acts of terror. Sixty percent of all members were reported by Freedom House to repress civil liberties. In both cases, the percentage of repressive members has grown substantially over time.52

Data on repression, including coding rules, are described in the following section.

Membership in preferential trade agreements standards: Percent repressive

Hafner-Burton53

has studied the selection process for hard agreements more systematically, controlling for domestic political institutions, economic development, and social movement mobilization across the period 1976 to 2002. Multivariate analyses of membership selection show that repressors are no more or less likely than protectors to select agreements with hard standard. Violators join these agreements almost as often as protectors. Rather, selection is driven strongly by level of institutionalized democracy and economic development. Poor democratizing states in need of economic resource are most likely to select hard agreements. These states are often but not always repressive. Moreover, there is no systematic difference between repressive states' selection of hard compared to soft standards.There is strong evidence that PTAs have influenced their repressive members' human rights behaviors by direct coercion—where contract obligations have been ceased with a target abuser, a set of demands for policy change have been issued, and new behaviors have consequently been adopted.54

See Fierro 2003; and Hazelzet 2004 for detailed examples in the European context, as well as European Council 2003.

Rwanda was a nonreciprocal trade member of the EC under the Lomé IV Treaty, which contained a human rights clause guaranteeing member commitment toward the improvement of basic human rights as a fundamental condition of market access.55

There have been at least eleven cases of active suspension of benefits supplied by the EC agreements with the ACP since 1996 alone.

EC action in the Rwandan case was challenged by unilateral action on the part of the French government, which chose to circumvent the financial sanctions at the Community level by continuing to supply the Rwandan government with aid. See King 1999.

The EU-Rwandan relationship entered into its third phase in 2000 with the 8th EDF, transitioning from rehabilitation to long-term development with more than 20 million Euros allocated for projects supporting good governance and justice. See the EC's Development available at 〈http://europa.eu.int/comm/development/〉. Accessed 10 March 2005.

Before the first transfer of resources could take place, the Rwandan army evacuated a refugee camp, violating the rights of many people. In direct reaction, the Commission suspended payment and EC ministers appealed to the Rwandan government to investigate the massacre and to arrest and detain the perpetrators as a precondition for payment. Resistance by the government to impose sanctions on members of the army led to the unconditional withholding of funds until sanctions were implemented. In 1995 the government agreed to prosecute those responsible, and the Commission conditionally reinstated payments under Lomé.58

Influence was direct and actively coercive.59Coercion in Myanmar demonstrates a similar process of influence. In 1996 the human rights clause of the Generalized System of Trade Preferences (GSP) was also successfully applied against the Union of Myanmar for alleged use of forced labor. See Brandtner and Rosas 1999.

In two similar cases, human rights reforms were initiated in both Togo and Fiji through direct coercive measures enacted under a hard PTA with the EU. In the case of Togo, following unsuccessful political consultations, the EC enacted Article 366a—the suspension clause of the Lomé IV Convention—in reaction to violation of democratic and human rights principles enshrined in the PTA, including serious irregularities in the application of political and civil rights.60

The Council decision was adopted in December 1998. See European Commission 1998a.

See Bulterman 1999; and Fierro 2003.

Evidence also shows that PTAs have at times been influenced by threat of sanction without implementation. Pakistan is one such case. The Pakistani government has long had trade relations with Europe. The EC's generalized system of preferences (GSP) establishes protective labor conditions with Pakistan on the importation of certain industrial and agricultural products.63

The GSP is a unilateral preferential instrument as compared to bilateral PTAs such as Lomé and Cotonou. There are currently two forms of standards regulated through the GSP, recognized in Regulations 3281/94 and 1256/96. The first is a negative provision: if a beneficiary country fails to provide internationally recognized workers rights, the country may be deprived, unilaterally, of GSP eligibility for selected articles. The second is a positive provision known as the “special incentives arrangements”: developing countries can apply for further preferences if they can demonstrate the complete implementation of standards in ILO Conventions combating forced labor and child labor, and protecting the freedom of association, the right to collective bargaining and nondiscrimination in employment. Note that Pakistan is not a member of the special arrangement.

European Parliament Resolution, 14 December 1995.

Brandtner and Rosas 1999. In a related case, trade preferences under the GSP were suspended with Burma in 1997 because of the existence of forced labor.

Brandtner and Rosas (1999) identify a Commission statement that reveals the Community's strategy in this case:

The overriding objective of the procedure, during which contracts are established with the authorities of the countries concerned, is to bring about progress on the ground by encouraging the countries concerned to pursue a qualitative social development, a process the Community backs up with complementary schemes. Preferences are withdrawn as a last resort, if the first two stages have come to nothing.66

Ibid., 717. It is during this period that the Commission began negotiations with Pakistan to conclude a Third Generation Cooperation Agreement, containing ever-stronger obligations to protect human rights. In 1999 signature was delayed repeatedly as a direct result of Pakistan's nuclear testing and human rights abuses, while a further set of conditions were imposed for membership. Signature of the new agreement, which is nonpreferential, took place under the new government of President Pervez Musharraf in 2001, but has not yet entered into force. The EC's External Relations is available at 〈http://europa.eu.int/comm/external_relations/pakistan/intro/index.htm〉. Accessed 28 March 2005. Note that in the wake of the terrorist attacks on 11 September 2001 against the United States, the EU granted Pakistan an inclusive package of trade preferences.

Human rights reforms have similarly been initiated in the Comoros Islands and Niger under threat to enact measures supplied by a hard PTA. In both cases, suspension of market access under Lomé was threatened by the EC following military coups leading to human rights violations. Substantial reforms by each government to comply with the EC's demands were initiated and cooperation was conditionally reinstated during consultations in lieu of suspension.67

Still other cases offer evidence that some PTAs influence through coercion coupled with persuasion. Slovakia is a strong case.68

Other related cases of successful coercion toward compliance with human rights norms include the EC's trade policy toward certain countries of the former Yugoslavia. See Brandtner and Rosas 1999.

See Bulterman, Hendriks, and Smith 1998; and Nowak 1999. Human rights abuses were also identified in the cases of Bulgaria and Romania, although violations did not technically violate the Copenhagen criteria for suspension of negotiations toward agreement. The Commission, through comprehensive annual evaluations, nevertheless articulated human rights reforms to be undertaken in both countries. See Fierro 2003, 142. Negotiations toward accession have been stopped in the case of Turkey as well, where violations of human rights have long been the primary obstacle to further integration.

In the subsequent phases of negotiations, the Commission cites substantial improvements in respect for civil and political rights in Slovakia, including support for civil society organizations and protection of the rights of minorities.71

It is important to remember that negotiations over EU membership represent the best instances of PTA influence. The EU is a PTA in the rare form of an economic union, offering a wide range of benefits that far exceed almost all other forms of preferential trade (such as free trade agreements, customs unions, and common markets). Nevertheless, negotiations over accession to the EU provide a prime example of PTA influence at its best.

European Commission 1999c. The central form of coercion in this case was enacted through the suspension of negotiations toward an accession agreement rather than suspension of the existing Europe Agreement, which also contained a hard human rights standard.

Côte d'Ivoire's trading relationship with the United States demonstrates a similar process of influence through coercion, although influence has been limited and confined to workers' rights in the export sectors. The African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) of 2000, which is an autonomous U.S. trade instrument signed into law as Title 1 of The Trade and Development Act of 2000, provides concrete market incentives for certain African states to liberalize their economies. The agreement aims to increase trade and investment in the region, while pressuring governments through the implementation of hard standards to promote the basic observance of human rights as a fundamental principle of trade, with specific attention to workers' rights. Côte d'Ivoire has been a candidate government since 2000, although the government (brought to power by military coup), was repeatedly denied trade benefits by the U.S. trade representative, “largely because of concerns related to rule of law, human rights, political pluralism, and economic reform.”74

Although violations of civil and political rights were a serious problem in both rebel and government areas of control, the United States recently granted Côte d'Ivoire membership in exchange for several minor advances toward protection of workers' rights. Specifically, the government agreed to support a protocol initiated by the U.S. Chocolate Manufacturers Association to address forced and hazardous child labor in the cocoa sector, which is one of the largest agricultural sectors and, together with coffee, accounts for three quarters of the country's export earnings. The government also began drafting legislation to conform to ILO conventions, as requested by the U.S. trade representative.75

Reforms, although limited, have taken place to gain trade membership. Côte d'Ivoire's exports under the agreement were valued at roughly $50 million in 2002, representing 13 percent of the country's total exports to the United States. While the United States used market access to press for reforms of labor rights, the EU opened consultations under Article 366a of Lomé to press for improvements in civil and political rights. The Commission recognizes that progress has been minimal but gradually improving.76These cases show clear instances where an agreement with hard standards influenced a repressive government to improve specific human rights practices after joining.77

For more examples, see Hazelzet 2001. In many cases, coercion has taken place during negotiations towards the formation of a hard PTA. Negotiations toward the formation of a Partnership and Cooperation Agreement between the EC and Belarus, for example, were suspended following the 1996 deterioration of human rights and made conditional upon reforms. See Fierro 2003.

There are several examples where PTAs with hard standards have failed to bring about compliance with human rights norms, either because the target government has chosen to forgo side payments in exchange for reforms, as in the case of Zimbabwe, or because the supplier lacks the political resolve to effectively coerce, as in the cases of China and Russia. See Miller 2004 for examples. Application of hard standards is selective and merits a separate analysis.

Moreover, human rights conditionality is by no means without its critics. Several lessons have emerged from theses cases that suggest limits to PTA capacity to shape human rights.79

See Crawford 1998; and European Commission 2000b and 2000c.

The United States, for example, routinely dismisses or postpones country petitions under the Generalized System of Preferences for violation of labor rights (OECD 1996), while various member states of the EC have shown clear limitations of political will to enforce negative PTA measures toward several former colonies. King 1999.

This article proceeds under the working assumption that hard PTAs supply a positive degree of credible threats and material incentives. However, PTAs may actually vary in their supply of credibility and incentives, suggesting the use of a weighting scheme to sort institutions. Although desirable, such a weighting scheme is hard as a practical matter, and as other scholars of organizations have noted, there is little extant theory to guide the effort (Oneal and Russett 1999). Further research into how PTAs vary in their incentives and credibility would be extremely useful, but is beyond the immediate scope of this article.

To test these theoretical implications more systematically, it is important to consider the domestic political and economic characteristics that are thought to influence repression of human rights. I begin by estimating the following model:

This study follows an increasing number of human rights scholars in the use of data measuring political terror. The dependent variable, repressionit, offers information about murder, torture, or other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment; prolonged detention without charges; disappearance or clandestine detention; and other flagrant violations of the right to life, liberty, and the security of the person. I draw on two existing data sources. Poe and Tate offer data on 153 governments' reported levels of repression (or political terror) from 1976 to 1993.84

For details, see Poe and Tate 1994. Data are available from 〈http://www.psci.unt.edu/ihrsc/poetate.htm.〉 Accessed 10 March 2005. My thanks to Steven Poe and his team at the University of North Texas for sharing their data.

Data are available from 〈www.unca.edu/politicalscience/faculty-staff/gibney.html〉. Accessed 10 March 2005. My thanks to Mark Gibney and his team at the university of University of North Carolina–Asheville for sharing their data.

Coding rules are described in the Appendix 2.

Descriptive statistics and associations, 1972–2002

The first set of independent variables, repression(1)it−1, repression(2)it−1, repression(3)it−1, repression(4)it−1, are binary indicators measuring a state's previous level of repression. They are included in place of the standard lagged dependent variable to account for dependence across the categories of the dependent variable over time.87

Because repressionit is treated as a nonlinear dependent variable, it is not appropriate to control for autocorrelation through the standard treatment of repressionit−1 as a lagged linear dependent variable. The inclusion of four dummy variables is a nice alternative to the problem of correlated categories of repression within a state across time.

It is important to control for three independent variables that capture elements of the domestic political context. First, democracyit−1 measures Polity IVd regime characteristics, coded by Jaggers and Gurr. The well-known variable takes on values ranging from 10 (most democratic) to −10 (most autocratic).88

Jaggers and Gurr construct a democracy index from five primary institutional features. For a detailed explanation of the data, see 〈http://www.cidcm.umd.edu/inscr/polity/〉. Accessed 10 March 2005.

See Henderson 1993; and Poe and Tate 1994.

It is equally important to control for three independent variables that capture elements of the domestic economy. tradeit−1 and investmentit−1 control for the possible effects that international financial and market transactions may have on human rights, independent from the international economic institutions. Past studies provide evidence that global economic flows shape government repression of human rights, either encouraging governments to improve protection of human rights, or promoting repression.91

I draw on data from the World Bank in order to measure these flows in the broadest sense possible. tradeit−1 measures the sum of a state's total exports and imports of goods and services measured as a share of gross domestic product. investmentit−1 measures the sum of the absolute values of inflows and outflows of foreign direct investment recorded in the balance of payments financial account.92This measure includes equity capital and reinvestment of earnings, as well as other long-term and short-term capital taken into consideration by a variety of human rights scholars.

In both cases, I include alternative measures of trade and investment as a check on robustness. See Hafner-Burton forthcoming.

Finally, pcgdpit−1 measures GDP per capita in constant US dollars. Many studies on human rights practices examine the effects of economic development. Mitchell and McCormick proffer the “simple poverty thesis,” a commonly accepted view that lack of economic resources creates fertile ground for political conflict, in many cases prompting governments to resort to political repression.94

In an advanced economy where people are likely to have fewer grievances, political stability is often achieved more easily, reducing the likelihood of human rights violations.95See Pritchard 1989; and Henderson 1991.

I analyze the effects of state commitment to HRAs and PTAs by introducing three core variables. In order to test Hypothesis 1, I consider state commitment to implement human rights agreements, hrasit−1. Specifically, I consider ratification, succession, and accession to two treaties designed to influence political terror and civil rights, and thus directly related to the dependent variable: the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the Convention Against Torture. hrasit−1. is an ordinal variable ranging from 0 to 2, derived from the total number of the two treaties that a state i has ratified into national law in time t.96

In order to control for the potential differences in effect between ratification, on the one hand, and succession and accession, on the other hand, I compute a second coding of this variable, hras_ratit−1 that counts only ratifications. In order to control for the possibility that the effects of ratification do not take place immediately, but rather over time, I compute a third coding of this variable, hras_yearsit−1, that counts cumulative years since ratification of the treaties. I report any discrepancies with the estimates of hrasit−1 in the footnotes.

Next, I consider state commitment to trade through PTAs offering human rights standards. Coding state membership in PTAs is not as straightforward as coding state ratification of human rights law. Of the more than 200 regional agreements today in effect, many states belong to several agreements simultaneously. In contrast to international human rights law where all states in the international system are eligible to join, PTAs also limit potential membership to a core economic region of states. All states are thus not eligible to belong to all agreements, and all PTAs do not incorporate human rights standards. Consequently, I test Hypotheses 2 and 3 using two binary measures of state membership in PTAs with human rights standards.97

A state with multiple agreements but minimal human rights standards may be more likely to shirk their human rights commitments associated with membership if they can gain the benefits of trade association through other memberships that do not impose conditionality. I also compute proportions in order to consider a state's commitment to PTAs with human rights standards relative to their overall commitment to PTAs.

I coded each policy outcome using content analysis of all PTA formal contracts, including treaties, protocols, and other forms of amendments. For each agreement, I assigned yearly values measuring membership of all states in the international system, the explicit98

Explicit here refers to those documents using the word “right” or “rights” to refer to human, worker, women, children, migrant, civil or other rights codified by the United Nations human rights legal regime. I do not include intellectual property rights or other usages of the terms that do not refer to one of the above categories.

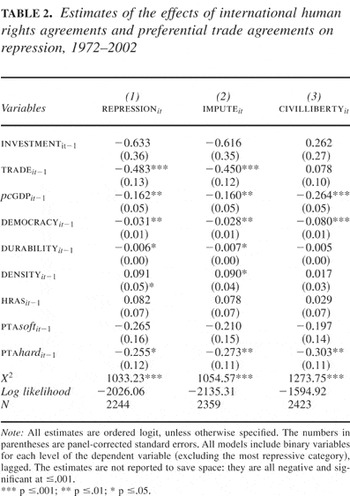

Column (1) of Table 2 reports ordered logit estimates of the parameters in equation (1). Although I propose several unidirectional hypotheses, I report two-tailed test statistics for all parameters. State commitments to comply with HRAs and soft PTAs do not systematically lead to decreasing repressive behavior in the following year. Quite the contrary, hrasit−1 and ptasoftit−1 have no significant effects on the likelihood of repression.99

The finding on HRAs is consistent with recent empirical work by Hafner-Burton and Tsutsui 2005; and Hathaway 2002.

Estimates of the effects of international human rights agreements and preferential trade agreements on repression, 1972–2002

I compute predicted probabilities of repressionit to interpret these results. Table 3 displays the probabilities, given Model (1), that a state employing repression in time 1 will employ different levels of repression in time 2. For example, the first two rows presents the probabilities that a state with a repressionit level of 5—an extreme abuser—will remain an extreme abuser or reform behaviors (to be a level 4, 3, 2, or 1) in the following year. The first of these rows shows probabilities calculated when a state belongs to no hard PTAs, while the second shows probabilities calculated when a state belongs to at least one hard agreement, all else at the mean.100

ptasoft is held at 0.

Predicted probabilities of repression across time: Hard preferential trade agreements, 1972–2002

The probabilities show quite simply that states belonging to hard PTAs have a lower probability of repressing human rights than states without memberships. A level 4 abuser, for example, is 6 percent more likely to reduce repression in the following year if they belong to a hard agreement, and 2 percent less likely to backslide into more abuse. Repression, however, is sticky, and changes are partial rather than absolute. States are likely to hold to status quo behaviors over time, and when they do reform, repressive states are most likely to move to the next category of repressionit (from a 3 to a 2), rather than to skip categories (from a 5 to a 1).

It is important to consider the robustness of the dependent variable by considering different samples and sources. To this end, I offer two additional measures of the dependent variable and reestimate ordered logit models in columns (2) and (3) of Table 2. imputeit imputes missing values of repressionit for 114 state-years during which Amnesty International did not produce annual reports. This variable is a robustness check against possible bias in Amnesty International's selection of state-years to report. Data were imputed for missing years on repression data coded from the U.S. State Department annual reports of political terror and several partisan variables in order to control for possible bias from the State Department—such as UN General Assembly voting agreement with the United States.101

The imputed values were tested by randomly eliminating 150 Amnesty scores and then correlating the imputed values with the true values, at a correlation of .91. I thank Erik Voeten for undertaking these imputations and for sharing his data.

civillibertyit offers information about repression of civil rights collected annually by Freedom House. Civil liberties include the freedom of expression, assembly, association, education, and religion, protected by an equitable system of rule of law, as well as freedom from political terror. Each country is assigned a value ranging across seven levels of behavior, from strong protection to extreme repression. The variable offers information from 1972 to 2001, on a total sample of 185 states.102

Data and complete coding information are available from 〈http://www.freedomhouse.org/ratings/index.htm〉. Accessed 10 March 2005.

Table 4 offers three additional robustness checks. Column (1) tests for a European influence. Only 12 percent of states belonging to a hard PTA do not also belong to trade agreements with the EU, and the best information about the ways in which hard agreements influence human rights comes from EU case studies. It is thus possible that PTA influence is a European phenomenon rather than a global one. States with stronger institutionalized trade ties to the EU may be more likely than states with weak ties or with no ties to be influenced by hard PTAs. The limitations of the statistical data make it impossible to analyze the effects of these agreements past 2002, and several PTAs have adopted some measure of hard standards since this time. However, I control for this possibility to the best extent possible by including a new variable. euit−1 measures the degree of trade integration between a state i in year t and the EU, coded by the number of shared PTAs. The findings show that the influence of hard PTAs is not driven by trade integration with the EU alone, although the EU is certainly the largest supplier.

Additional Robustness checks: Estimates of the effects of EU trade relations and time effects on repression, 1972–2002

Column (2) controls for fixed-time effects, which do not change the substantive results for hard PTAs. Fixed-time effects are useful because they allow one to consider the possibility that time is driving the result; that a norm of human rights has emerged and developed and spread during the past thirty years that accounts for why states more and more sign contracts with human rights standards and implement better practices. The results, however, show us that the institutional effects are not simply time-dependent. Controlling for every year in the sample, hard PTAs have the expected effect.103

In order to more systematically address concerns of endogeneity, I calculate two-stage least-squares estimates assuming ptahardit as endogenous. Coefficients remain consistent in sign and significance.

Finally, column (3) considers the issue of economic leverage. PTAs influence because they coerce actors into adopting behaviors they might not otherwise adopt, providing economic incentives to actors that value them. Testing economic leverage directly, however, proves to be a difficult task. As a preliminary step, I include two interaction terms between ptahardit−1 and the GDP and population variables, under the logic that the gains from integration are likely to be more significant for smaller and poorer nations.104

I would like to thank an anonymous reviewer for this suggestion.

I also include a binary variable to control for the effects of war on repression of human rights. In times of warfare, governments tend to be more coercive, defending their authority against internal challenges to the state, often through increasing political terror. See Poe and Tate 1994. They may also face armed opposition groups with preferences for human rights that are unlikely to be coerced by RTAs. warit−1 is a dichotomous variable collected by the Correlates of War Project under David J. Singer and Melvin Small (ICPSR Study 9905). It equals 1 if a country is at war, and zero otherwise. States at war are significantly more likely to repress human rights, although the results for hard PTAs remain negative and significant. I also interact democracyit−1 and durabilityit−1 in order to see if the time horizon of institutionalized democracy changes the results. The results for hard PTAs remain consistent.

When do states comply with international rules governing human rights? It has been often accepted that states regularly come to change their human rights behaviors when they are persuaded by international actors and institutions: international institutions can change states' preferences for behavior even when coercive instruments of enforcement are not available.106

Although influence through coercion is almost always beyond the scope of HRAs, many scholars that remain convinced of HRA influence without hard standards also recognize that coercive instruments can be important tools to enforce better practices, and that human rights advocates frequently employ material incentives to proffer norms of better behavior. See, for example, Keck and Sikkink 1998; and Risse, Ropp, and Sikkink 1999. Others support the general views of Chayes and Chayes 1998 by arguing that coercive enforcement is likely to be unproductive, imposing high costs with little behavioral gain. See note 22.

Strategies of economic coercion can also have persuasive effects overtime, as repeated punitive interactions may contribute to the recognition and domestic internalization of the disputed norm. For a similar argument with respect to unilateral economic sanctions, see Cleveland 2001b.

This argument has three core implications. First, human rights regimes alone rarely create the conditions necessary for state compliance with human rights because they are almost always soft, lacking the necessary mechanisms to supply strong incentives and commitment instruments to outweigh defection. Second, material and political rewards are often a more effective (and compatible) incentive structure to support the initial stages of compliance. Third, a growing number of PTAs have become part of a larger set of governing institutions enforcing better human rights practices. These agreements can supply limited human rights mandates and influence some governments to make marginal improvements in certain human rights behaviors; they can enforce the initial stages of compliance that most HRAs cannot.

It could easily be argued that PTAs are not ideal forums for human rights governance; that the WTO would be more effective in enforcing better practices; and that better designed HRAs would solve the problems of compliance. Nothing could be closer to the argument proposed here. International institutions have the greatest influence over state compliance with human rights principles when they offer substantial gains with some kind of coercive incentives, perhaps coupled with strategies of persuasion, to change the costs and benefits of repressive actors' behaviors. If the member states of the WTO could agree on a human rights clause linking the terms of trade to the protection of human rights, it could potentially begin to leverage some influence on world repression, and it could certainly empower human rights advocates fighting for reform.

The WTO today, however, provides no formal guidance with respect to member state compliance with international human rights laws or principles. Attempts to adopt even soft standards protecting workers rights have failed time and time again and they appear unlikely to succeed anytime in the near future.108

The adoption of rules designed to protect citizens' rights into trade agreements had limited precedent in the pre-GATT era, although the issue of human rights emerged most forcefully during the Uruguay Round. See Francioni 2001. Several countries sought to reintroduce a narrow set of labor rights into the legal architecture of the organization. Perceiving this initiative as protectionist and imperialist, many countries of the developing world launched a campaign to prevent the incorporation of core labor standards into global trade doctrine. See McCrudden and Davies 2000. These disputes eventually led to the 1996 Singapore compromise declaring that the WTO is not the competent body to redress concerns for members' compliance with international labor laws. The compromise was upheld in Seattle (1999), Doha (2001), and Cancun (2003).

PTAs, then, are certainly not ideal forms of human rights governance and they are not a replacement for human rights laws. They are among the only existing international institutions with some capacity to enforce compliance, and they may prove to be one of the more effective available means of implementing very basic human rights values into practice, although partial and imperfect.

Human rights behaviors: Percentage of states that repress and that ratify human rights agreements

Preferential trade agreements with human rights standards

Membership in preferential trade agreements standards: Percent repressive

Descriptive statistics and associations, 1972–2002

Estimates of the effects of international human rights agreements and preferential trade agreements on repression, 1972–2002

Predicted probabilities of repression across time: Hard preferential trade agreements, 1972–2002

Additional Robustness checks: Estimates of the effects of EU trade relations and time effects on repression, 1972–2002