Many countries expend tremendous effort fighting terrorism, despite the relative weakness of most terrorists.Footnote 1 To explain this paradox, researchers often highlight how public opinion shapes elected officials’ incentives following terrorism.Footnote 2 In turn, public opinion about terrorism is thought to be primarily influenced by fear and overestimation of risk following news coverage of attacks on civilians.Footnote 3

However, several empirical regularities belie the centrality of fear and civilian risk in shaping public opinion about terrorism. First, though citizens often perceive higher threat following terrorist attacks, only a minority report high levels of fear or anxiety.Footnote 4 The minority that do experience high fear are often less supportive of aggressive counterterror policies,Footnote 5 even though publics in general tend to be more militant following terrorism.Footnote 6 The public also reacts more strongly to out-group perpetrators than in-group ones, even when they are similarly violent.Footnote 7 Together, these findings suggest that the dominant driver of public opinion about terrorism is often not fear and a desire to reduce personal risk, but anger and a desire for vengeance against perpetrators whom citizens deem worthy of punishment.

I investigate these distinct emotional mechanisms using a parallel-encouragement experiment in the United States (n = 5,499). This design is explicitly structured to test causal mechanisms by manipulating both exposure to news about different types of terrorism and the encouraged emotional response.Footnote 8 I find that, while both anger and fear increase support for retaliation, anger is both a more dominant emotional response and the only emotion that, when induced, increases punitive motives for retaliation. Inducing anger also significantly shrinks partisan gaps in support for retaliation following attacks by different perpetrators, providing further evidence of anger's causal role in shaping public attitudes.

Because public opinion can influence state security policy choices and shape militant incentives,Footnote 9 the degree of public anger following terrorist violence has problematic implications for retaliatory spirals of conflict.Footnote 10 If terror attacks primarily engender outrage and the desire to punish perpetrators, they could incentivize electorally minded leaders to exact vengeance, even if this engenders a “backlash” that increases future terror risk.Footnote 11 These results thus shed light on a core puzzle in the terrorism literature: why groups that use terrorism rarely achieve concessions yet often goad democratic governments to overreact with military action, making terrorism more effective as a strategy of provocation rather than attrition.Footnote 12 This research also highlights the increasingly partisan emotional pathways through which terrorism shapes attitudes toward different perpetrators, pointing to potentially changing in-group/out-group perceptions in an era of heightened partisan polarization and posing a thorny challenge for leaders seeking to effectively counter both threats.Footnote 13

Fear and Risk: The “Terror” in Terrorism

Terrorism has a strong effect on the political attitudes of the mass public. After terror attacks, citizens prefer costlier counterterror policies, at times seeking out concessions, but more often supporting more militant policies and parties.Footnote 14 The predominant explanation for these preferences, in both scholarly and public accounts, centers on perceptions of risk and the emotion of fear.Footnote 15 Whether due to rational updating about personal risk following attacks on civilians or inflated risk estimates stemming from cognitive biases, citizens are thought to experience increased fear after terrorism that, in turn, shapes their political attitudes.Footnote 16

The identity of terrorism's victims is central to this conception of fear's role in influencing public opinion. Citizens concerned with their personal safety witness attacks on civilians and update (rationally or not) their assessments of their own future risk of being targeted, particularly when the victims are perceived as “similar to them.”Footnote 17 These elevated risk perceptions, even if vastly overestimated,Footnote 18 make citizens more fearful after terror attacks than they would have been had the violence not targeted civilians.

However, few have directly examined the centrality of this posited emotional pathway or the relative importance of civilian victimization in shaping public opinion. The importance of fear is simply assumed, perhaps because the public does report increased levels of threat in the wake of terrorist violence and routinely lists terrorism among their top security concerns. Yet, the public's concern about terrorism is a measure of threat perceptions, not the emotional response of fear. Though “threat” and “fear” are often used interchangeably in discussing public concerns about terrorism, they are not the same thing. Fear is an emotional response to threat, and it is only one of many possible emotional responses.Footnote 19 Anger is another, and has distinct implications for citizens’ political motivations and attitudes.

Anger and Morality: The Politics of Retribution

Anger is a powerful driver of political attitudes and behavior and is particularly important in violent political conflict.Footnote 20 Anger's deep-seated impact is likely because anger is a moral emotion, elicited not simply when a negative, threatening event occurs but when that event or action is perceived as both purposeful and unjust.Footnote 21 Anger is thus rooted in value-based appraisals of the legitimacy or fairness of an action and the blameworthiness of the perpetrator and may moralize and polarize political attitudes.Footnote 22

Cognitive-appraisal theories of emotion posit that anger and fear, though both negatively valenced, stem from distinct perceptual foundations and thus lead to different behavioral tendencies.Footnote 23 Fear stems from an appraisal of heightened personal risk or weakness, activating an avoidance tendency. Anger is triggered by appraisals of comparative strength, combined with attributions of blame toward someone perceived to have transgressed norms, engendering an approach tendency. The emotions are not mutually exclusive—self-reports of fear and anger are often highly correlated—but, to the extent that individuals feel both emotions, one is usually experienced with higher intensity than the other and so will be a more prominent driver of political attitudes.Footnote 24

From a theory-of-ethics perspective, fear is associated with a consequentialist logic, while anger engenders deontological thinking: actions must follow moral rules rather than simply achieving the best outcomes.Footnote 25 This has implications for the motives underlying public support for retaliation and conciliation following terrorist violence. For fearful individuals, preferences for retaliation are likely motivated by defensive impulses to prevent future violence, while, for angry individuals, support for retaliation may be motivated by offensive aims,Footnote 26 punishing the perpetrators simply because they deserve it. These different retaliatory logics parallel the motives underlying public opinion on criminal justice: rehabilitation, incapacitation, deterrence, and punishment.Footnote 27 The first three motives are consequentialist, designed to reduce the future risk of violence by the perpetrators themselves or by other, like-minded perpetrators. Punitive motives, on the other hand, are deontological, focused on avenging historic wrongdoing.Footnote 28 Of the four, punitive motives have repeatedly been found to be the most dominant predictor of support for harsh criminal justice policies, including the death penalty.Footnote 29 Political science research has documented a similar connection between punitive motives and support for the use of military force.Footnote 30 However, the emotional antecedents of these retributive preferences in foreign policy have been less well studied.Footnote 31

I theorize that the reason exposure to terrorism news so often increases public support for retaliation and decreases support for concessions is because these attacks make people angry and this, in turn, makes punishment a primary motive when deciding which policies to support (Figure 1). While fear would generate a flight or fight response that could increase support for retaliation in some cases,Footnote 32 it would be motivated by an impulse to prevent future violence.Footnote 33 In contrast, angry citizens’ support for retaliation should be motivated by a desire not simply to prevent future attacks but also to punish past ones. Moreover, while fear can increase risk aversion and support for conciliatory policies in some cases,Footnote 34 angry publics should uniformly oppose concessions for attackers they deem worthy of punishment. This means that, relative to fear, public anger in the wake of terrorism could increase the range of circumstances under which citizens would support retaliation.

FIGURE 1. Theorized Causal Path of the Effect of Terrorism News on Attitudes

Innocents, Out-Groups, and Partisanship

Why is terrorism so likely to evoke anger and the desire for retributive retaliation? First, terrorist attacks often target civilians. Attacking these blameless “innocents” transgresses modern norms regarding the use of force and may be seen as particularly extreme or unjust by the public,Footnote 35 a core appraisal tied to anger.Footnote 36 Thus, public anger and support for retaliation may be higher after attacks on civilian, as opposed to military, targets. On the other hand, terrorist attacks may trigger anger connected to the identity of the perpetrators: an ethnic or religious out-group. Individuals have been shown to express more anger and support greater punishmentFootnote 37 toward negative actions by out-group offenders,Footnote 38 particularly when the out-group is perceived as “entitative.”Footnote 39 Anger can also be exacerbated by the ultimate attribution error, an intergroup cognitive bias whereby negative actions by out-group members are more readily attributed to character flaws.Footnote 40 Indeed, though scholarly definitions of terrorism focus on the victims as the defining feature of terrorist (as opposed to guerrilla) violence,Footnote 41 the mass public readily labels attacks on military targets as terrorism,Footnote 42 but is less likely to label white attackers as terrorists, even when they target civilians.Footnote 43 Collectively, this evidence suggests that public anger following a terror attack is driven more by the perceived blameworthiness of out-group, as opposed to in-group, perpetrators.

The public's emotional responses to terrorism may also be shaped by citizens’ preexisting political attitudes. While past studies have demonstrated that jihadist terrorism increases hawkish preferences across the political spectrum,Footnote 44 responses to terrorism have become increasingly politicized. In the United States, Democrats have grown wary of the “war on terror” against jihadist groups and more concerned about other terror threats, including a resurgent white nationalist movement.Footnote 45 The growing association between the Republican Party and the “alt-right” movement under the Trump administration, likewise, may have dampened support from Republicans (and increased support from Democrats) for policies to counter domestic white nationalist groups.Footnote 46 This could be due to a recategorization of salient in-group/out-group dynamics in an era of heightened partisan polarization.Footnote 47 Democrats may now view white nationalist perpetrators as part of a partisan out-group, rather than as ethnic and religious in-group members.Footnote 48 Moreover, Democrats may be more likely to perceive the victims of white nationalist violence as in-group members, due to their assumed partisan, ethnic, or religious affiliation. Since anger toward offenders is stronger when the victim is seen as an in-group member and the perpetrators as an out-group,Footnote 49 this recategorization may differentially shape the emotional and political responses of Republicans and Democrats to attacks by different perpetrators.

Research Design

The present research tests this theoretical argument using a preregistered survey experiment with a parallel-encouragement design that manipulates both exposure to terrorism news and the encouraged emotional response before assessing political attitudes (Figure 2).Footnote 50 The survey was conducted using Lucid Marketplace in March 2021 among 5,499 US adults, with rough census representation on age, region, gender, ethnicity, and partisanship.Footnote 51

FIGURE 2. Survey Flow

Manipulating both the treatment and mediator is an important innovation to directly test causal mechanisms in experimental studies, as it addresses the risk of post-treatment bias that could otherwise be induced by conditioning on post-treatment variables (i.e., experienced emotions) in a traditional design where only the treatment level is manipulated.Footnote 52

Experimental Treatments

The first treatment is exposure to a fictitious news report about a terrorist attack in the US that “killed at least two US citizens and wounded dozens more,” with two varying features: the victim of the attack (civilians at a mall or troops at a base) and the perpetrators of the attack (jihadists or white nationalists). Until debriefing, subjects believe this is a real article about a terror attack that happened the day before.Footnote 53 Importantly, exposure to terrorism news may have different effects than physical proximity to a terror attack.Footnote 54 However, in the US and many other Western countries, the vast majority of the public's real-world exposure to terrorism comes from media reports rather than personal experience.Footnote 55 Using news about terrorism as a treatment to assess the effects of terrorism on public opinion is thus a common approach.Footnote 56

Subjects in the natural mediator arm do not receive any emotion prime and are asked to write their thoughts on the article before proceeding to answer questions about their counterterror attitudes. Subjects in the manipulated mediator arms are exposed to a second treatment to induce different emotions: anger, fear, or reassurance. Because negative emotions—particularly anger—are theorized to be naturally high after exposure to terrorism news, the reassurance prime sought to dampen this emotional response to assess the effect of exposure to terrorism news, independent of the anger that follows. These arms use a well-established emotion induction called an autobiographical emotional memory task (AEMT).Footnote 57 Respondents are prompted to recall and write about aspects of terrorism that have led them to experience the assigned emotion strongly. This addresses two key threats to inference that otherwise impact the study of emotions in politics: ex ante characteristics that lead individuals to have specific emotional responses to terrorism, and the role new information about a threat plays in triggering the emotion.Footnote 58

Ethical Considerations

This study involves the use of deception. Research participants believe they are reading real articles, but these stories were developed by the researcher. Using fake or altered news stories attributed to real media is a frequent approach in experimental political science.Footnote 59 However, this deception can pose risks. For example, prior to debriefing, participants may experience emotional distress from reading news about political violence. There is also a concern that participants might become suspicious of news media and/or academic researchers after being made aware of the deception. It is thus important to consider whether deception is necessary for the research.Footnote 60

In this study, deception is critical because the experiment examines the role that visceral emotional reactions to encountering news about terrorism play in shaping citizens’ political attitudes. While hypothetical scenarios or abstract vignettes may be suitable for the study of some attitudes,Footnote 61 these tools are less well suited for inducing the strong emotional responses citizens feel after exposure to terrorism news. Indeed, abstract scenarios are particularly problematic when addressing issues concerning morality and justice,Footnote 62 as this study does, because research participants’ answers to “decontextualized hypothetical scenarios may not accurately reflect moral decisions in everyday life.”Footnote 63

Since experimental realism is so important to the design's validity, one might instead consider using real articles about past attacks. However, this too is problematic. Because real-world attacks naturally vary on so many dimensions, disentangling the effects of the attributes of interest (victim and perpetrator identity) on emotional and political responses to terrorism would be extremely confounded.Footnote 64 This problem is further compounded by the distinct ways the media covers attacks by different perpetrators.Footnote 65 Even if it were possible to identify two real attacks similar to each other except on the dimensions of interest, given the widespread real-world coverage, respondents are likely to have already developed various preconceived beliefs about the attacks and what should be (or already has been) done in response. These beliefs could be shaped by a host of longer-term processes that take place following terrorism, including elite framing,Footnote 66 making it nearly impossible to assess the independent causal effect of these immediate, bottom-up emotional reactions to terrorism news on the public's political attitudes.

Ultimately, this research investigates core questions regarding how the public responds emotionally to terrorism, shaping the incentives of political leaders formulating counterterror policy. Given these considerations, I conclude that deception is necessary to effectively assess the role of public outrage in potentially exacerbating vengeful cycles of terrorist and counterterrorist violence, a question of immense political importance with stark real-world consequences for the populations impacted by this violence.

In addition to the need for deception, the Principles and Guidance for Human Subjects Research of the American Political Science Association (APSA) outline four other considerations for researchers using deception: whether the study involves minimum risk of harm for participants; whether consent would have been withdrawn if participants had full knowledge of the deception; potential power imbalances between the researcher and participants; and whether debriefing of participants is possible.Footnote 67 I discuss each of these considerations, the various other APSA principles for human subject research, and the potential broader impacts of the use of deception for trust in media and researchers in section C of the online supplement.

Measurement

The core dependent variables in this study are respondents’ support for conciliatory or retaliatory policies against terrorists and, crucially, their rationales for supporting retaliation: punitive (“punishing the perpetrators for their wrongs”) or preventative (e.g., “incapacitating the perpetrators so they cannot commit future attacks”). Subjects are also asked to self-report the degree to which they feel various emotions about terrorism. Emotions are measured with a composite index, where anger is the average of anger, outrage, and disgust (α = 0.84) and fear is the average of fear, anxiety, and worry (α = 0.86). Previous research has found these measures load onto two distinct factors.Footnote 68

Hypotheses

The survey experiment tests eight preregistered hypotheses, with comparisons across different treatment arms providing causal leverage on different questions.Footnote 69 The first five hypotheses are tested using the natural mediator arms of the experiment, where subjects read news about terrorism but do not receive an AEMT task:

• H1: Exposure to news of an attack will increase support for retaliation and decrease support for conciliation with terrorists compared to no attack.

• H2: In particular, exposure to news of an attack will increase punitive rationales for retaliation against terrorists compared to no attack.

• H3: Exposure to news of attacks on civilian targets will not result in different levels of support for retaliation or conciliation relative to attacks on military targets.

• H4: Exposure to news of attacks by jihadists will increase support for retaliation and reduce support for conciliation relative to exposure to news of attacks by white nationalists.

• H5: Exposure to news of attacks by white nationalists will interact with partisanship such that Republicans will be less likely than Democrats to support retaliation and more likely to support conciliation.

The other three hypotheses leverage the double randomization of the parallel-encouragement design, examining subjects across the manipulated mediator arms of the study:

• H6: Exposure to news of any type of attack in conjunction with an anger prime will increase support for retaliation and decrease support for conciliation relative to news exposure in conjunction with a reassurance prime.

• H7: Exposure to news of any type of attack in conjunction with an anger prime will increase punitive rationales for retaliation against terrorists relative to both a reassurance and a fear prime.

• H8: Differences in political attitudes between respondents exposed versus not exposed to terrorism news will be smaller in the manipulated anger arms than they are in the natural mediator arms.

Results

Emotions and Exposure to Terrorism News

The first set of analyses compares the five treatment arms in the natural mediator arms. In four of these conditions, subjects are exposed to news stories about different types of terror attacks. These are compared to the control: subjects who read a nonpolitical story.

The dominant emotional response of subjects to terrorism news is anger rather than fear: 62 percent report higher anger than fear following exposure to terrorism news; only 18 percent report higher fear. A paired sample t-test of anger and fear within each news treatment arm indicates that self-reported anger is significantly higher than fear regardless of attack type (Figure 3a). These patterns are consistent across ethnicity, gender, religion, residence, education, and income. Moreover, after exposure to news of an attack, anger, but not fear, significantly increases, regardless of perpetrator or victim identity (Figure 3b).Footnote 70 In short, subjects are significantly more outraged after exposure to news of an attack, but are not significantly more terrified. This belies the popular narrative of terrorism's invariably fear-inducing effect on civilian populations.

FIGURE 3. Relative Levels of Anger and Fear in Response to Terrorism News

Effects of Exposure to Terrorism News on Political Attitudes

Given the prominence of anger following terror attacks, exposure to any form of terrorism news was hypothesized to increase support for retaliation and decrease support for conciliation (H1), while also increasing punitive rationales for the use of force (H2). I find, however, that exposure to terrorism news only marginally increases support for retaliation (Table 1, model 1) and does not significantly affect support for conciliation or punitive motivations.Footnote 71 These muted effects are surprising because past research has demonstrated a small but consistent rightward shift following terrorism, particularly in the US.Footnote 72

TABLE 1. Support for Retaliation by Terrorism Type and Partisanship

Notes: Table 1 displays the results of five OLS models regressing attack type on support for retaliation. Model 1: any attack compared to no attack. Models 2 and 5: military to civilian attacks. Model 3 and 4: white nationalist to jihadist attacks. Models 4 and 5 include a three-level partisanship variable interacted with attack type, with Democrats as the reference category. Natural mediator arms only. ^p<.10; *p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001.

On closer examination, it is clear that the small main effects are driven by heterogeneity in partisans’ responses to different forms of terrorism, as hypothesized in H5: Republicans are significantly less angry, punitive, and retaliatory than Democrats following an attack by a white nationalist, while the pattern is reversed for jihadists (Figure 4).Footnote 73 Because Democrats and Republicans have opposing emotional and political responses to news about different attacks, the overall effect of exposure to terrorism news on support for retaliation is small. Moreover, because Democrats are less supportive of retaliation at baseline, attacks on the military are actually marginally more likely to increase support for retaliation than attacks on civilians, and attacks by white nationalists are significantly more likely than attacks by jihadists to do so, in contrast to hypotheses H3 and H4, respectively (Table 1, models 2 and 3).

FIGURE 4. Interaction of Partisanship and Perpetrator ID on Responses to Terrorism News

Together, these results indicate that the level of anger after terrorist violence varies by both party and perpetrator identity, which may shape differential partisan support for retributive retaliation.

The Causal Impact of Anger

But does anger play a causal role in motivating support for retaliation among Democrats and Republicans, or is it simply a downstream consequence of ex ante political attitudes? To directly examine this question, we next turn to the manipulated mediator arms, analyzing attitudes across arms where the type of attack differed but the emotional prime was the same.

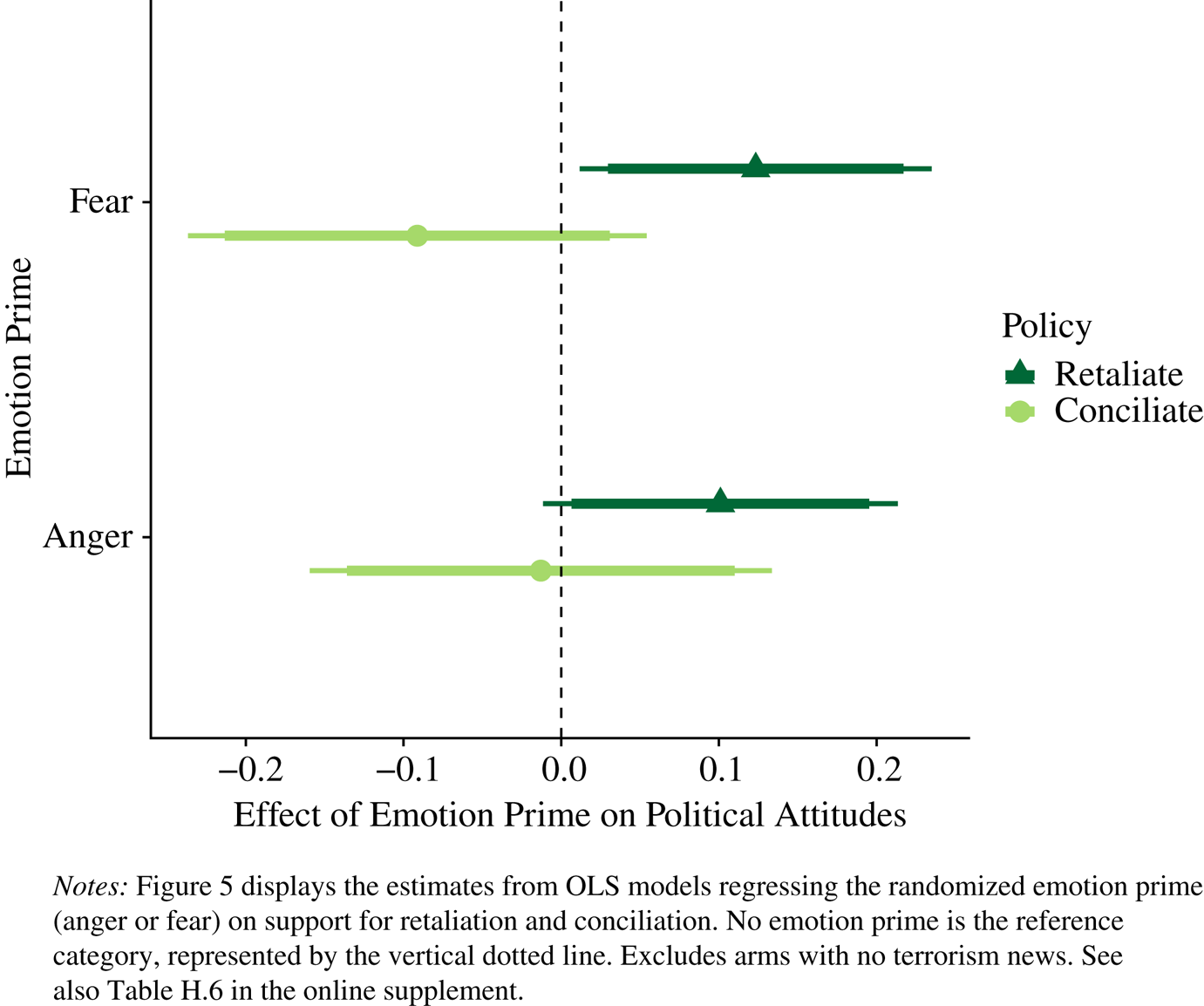

Two hypotheses were specified regarding the indirect effect of emotions induced in the wake of terrorism on political attitudes: both induced anger and fear will increase support for retaliation and decrease support for conciliation (H6); and only anger will increase the importance of punitive rationales in justifying this response (H7). Figure 5 illustrates preferences for retaliation and conciliation among those in the manipulated fear arms and anger arms as compared to those who received no prime.Footnote 74 While support for conciliation is unmoved, fear and anger both increase support for retaliation—however, note that the effect of anger (p = 0.079) is not as precisely estimated as that of fear.

FIGURE 5. Effect of Distinct Emotions After Exposure to Terrorism News on Political Attitudes

However, the rationales for these retaliatory preferences among fearful and angry respondents vary, as predicted. Inducing respondents to feel angry—but not fearful—significantly increases punitive rationales for the use of force (Figure 6). In the anger treatment, the coefficient on support for punitive motives (β = 0.137) is 2.5 times that in the fear treatment (β = 0.056).Footnote 75 This increased support for retributive retaliation among angry individuals is notable, given that individuals are likely to under-report the extent to which retributive motives guide their preferences.Footnote 76 In contrast, encouraging respondents to feel fearful only significantly increases the motive to incapacitate would-be attackers, as predicted by an appraisal framework that theorizes fear as an avoidant emotion primarily aimed at reducing future harm. There is thus a significant indirect effect of exposure to terrorism news that flows through the emotional experience of anger to shape punitive motives and support for retaliation.

FIGURE 6. Effect of Distinct Emotions After Exposure to Terrorism News on Punitive Rationales

The changes in underlying motives engendered by anger and fear help explain the different political attitudes partisans were shown to hold in the wake of attacks by different perpetrators. Inducing Republicans and Democrats to experience the same emotional reaction to jihadist and white nationalist violence, then, should reduce the partisan gap in support for retaliation, making the interaction of perpetrator identity and partisanship nonsignificant (H8).Footnote 77

This is indeed what we find. The partisan gap in political attitudes in conditions in which attacker ID varies, but the emotional prime (e.g., anger) is the same, are smaller than the partisan gap in the natural mediator arm of the study, where no emotional prime is given. Without priming emotions, the effect size of the partisanship–perpetrator interaction on support for retaliation is β = −0.72. When priming anger, it is much smaller: β = −0.33. This means anger experienced in the wake of exposure to terrorism news explains nearly half of partisanship's differential effect on support for retaliation following white nationalist versus jihadist attacks. This is primarily driven by changes in responses to jihadist violence, where partisan attitudes are more dissimilar at baseline (Figure 7). After receiving an anger prime, Democrats, who are otherwise significantly less retaliatory and punitive toward jihadists than Republicans are, adopt much more retributive preferences. For Republicans, on the other hand, induced anger leads them to adopt a similarly retributive stance toward white nationalists as they do toward jihadists.

FIGURE 7. Effect of Emotion Primes on the Interaction of Partisanship and Perpetrator ID on Attitudes

In short, when we make Democrats and Republicans feel similar levels of anger following different forms of terrorism, their subsequent motives and political attitudes become more closely aligned.Footnote 78

Anger and Fear After Real-World Attacks

The centrality of anger in motivating preferences for retaliation after terrorism is a key finding of this experiment. To explore the plausibility of anger's predominance in public reactions to terrorism outside of an experimental setting, I supplement this study with observational data, conducting a sentiment analysis of 922,217 tweets posted in the week following sixteen lethal terror attacks in the US since 2010.Footnote 79 Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC) sentiment-analysis software was used to give each tweet a score representing the percentage of words in the tweet present in the LIWC anxiety and anger dictionaries. For example, the following tweet about the San Bernardino attack received a high anger score: “Angered by the news of the San Bernardino mass shooting today; not just saddened, angered.” In contrast, this tweet following the El Paso Walmart shooting scored high on anxiety, but low on anger: “Im like so freaking terrified, I live in El Paso and the shooting is just ridiculous like im scared their gonna come to my area and its not safe right now.”

For nine out of sixteen terror attacks, paired sample t-tests indicate that the average anger score of tweets is significantly higher than the average anxiety score, while anxiety is significantly higher after only four attacks (Figure 8).Footnote 80 Thus, people are often more likely to express anger than fear after real-world terrorist violence, even in the immediate aftermath of these events, when fear would likely be at its height. Specifically, among these sixteen attacks, those perpetrated by white nationalists appear most likely to engender anger on Twitter. Given the partisan skewedness of the platform, with Democrats over-represented among all users and among the most prolific ones,Footnote 81 this trend is consistent with the experimental results: that partisanship and perpetrator identity interact to influence emotional and political responses to terrorism. While social media analysis has important limitations, these data strongly suggest that anger has played a predominant role in shaping public responses to many real-world terror attacks over the past decade.

FIGURE 8. Sentiment Analysis of Tweets Surrounding Real-World Terror Attacks

Discussion and Implications

This study shows that anger and the desire for retribution can shape citizens’ attitudes in the wake of terrorism. It thus provides a deeper understanding of the distinct emotional microfoundations driving public opinion about terrorism, with key implications for how we understand cycles of terrorist violence.

First, the dominant emotional response of citizens to exposure to terrorism news is often anger rather than fear. This may influence the strategic calculations of militant organizations. Terrorist tactics may help a weaker group provoke retaliation from a state, bringing the group followers and recruits in the long run.Footnote 82 However, the attack is unlikely to lead to concessions,Footnote 83 unless the group can sustain a large enough campaign to truly engender a feeling of vulnerability and fear in a target population. This may explain why studies that show terrorism “works” in securing concessions are often done in countries fighting civil wars.Footnote 84 This study thus contributes to a growing body of work assessing how affect shapes strategy in international conflict.Footnote 85

Second, anger experienced in the wake of terrorism increases citizens’ focus on punishing perpetrators, not just preventing future terrorism. This has problematic implications for cycles of political violence, as angry publics will likely pressure their leaders to retaliate under a broader range of circumstances than fearful ones, including when retaliation risks a terrorist backlash.Footnote 86 Interrogating these distinct emotional motivations undergirding public support for retaliation is thus important for understanding when political violence is likely to escalate into retaliatory spirals.Footnote 87

The increasingly partisan response of Americans to terrorist violence is another striking finding of this study. This is a stark departure from historic patterns, in which terror attacks often unified public opinion, such as following the Oklahoma City bombing and the September 11 attacks. These changes are likely driven, in part, by the increased politicization of terrorism in the US since the 2016 election of Donald Trump. However, polarization over counterterror policy was growing before the Trump administration and is also prevalent in other countries.Footnote 88 These partisan divides pose a difficult political dilemma for elected officials seeking to marshal public support for policies to counter both types of threats.Footnote 89 An important future direction for this work, then, is to examine the conditions under which attacks trigger more uniform (as opposed to polarized) public outrage. Based on the findings of this study, it is likely that changing perceptions of the in-group/out-group status of terrorism's victims and perpetrators may play a prominent role.Footnote 90

Finally, these findings have important policy implications for how leaders interact with their citizenry in the wake of terror attacks. For one, political elites may be overestimating the extent to which citizens are terrified of terrorist violence. If the public is angry rather than scared following terrorism, attempts by leaders to reduce public fear may backfire if citizens interpret this messaging as allowing blameworthy perpetrators to avoid punishment. This may be particularly challenging for dovish leaders.Footnote 91 Of course, the public's anger in response to terrorism also means hawkish leaders can seize on public outrage for electoral benefit and to pursue more aggressive counterterror policies.Footnote 92 In particular, moralized counterterror frames will likely garner more ready support from an outraged public than frames focused on risk reduction.Footnote 93 This may explain the frequent use of this rhetorical strategy by leaders, such as George W. Bush's famed “axis of evil” speech,Footnote 94 Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu's statement that “evil has to be resisted,”Footnote 95 and proposals for counterterror policies that emphasize punishment, such as Donald Trump's 2016 call to “take out” the families of suspected terrorists.Footnote 96 Thus, in the wake of terrorism, leaders are constrained by public anger and its increasingly partisan manifestations, but they also have significant power to channel this outrage into a range of potential counterterror policies at home and abroad.

Data Availability Statement

Replication files for this research note may be found at <https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/1OAEWL>.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material for this research note is available at <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818323000152>.

Acknowledgments

This research has benefited from discussions and feedback from so many colleagues it would be difficult to list them all here! Since this project builds on theories developed in my dissertation, I would be remiss if I did not thank my advisors Yuri Zhukov, Jim Morrow, Ted Brader, and Nick Valentino. I am also very grateful for constructive comments from workshop attendees at the WUSTL Junior Faculty and IR Workshops, University of Florida Research Seminar in Politics, University of Wisconsin IR Colloquium, and APSA Elections, Public Opinion, Voting Behavior, and Political Psychology Series. Any errors remain my own.

Funding

I am thankful for financial support for this project provided by the Weidenbaum Center at Washington University in St. Louis.