Founded alongside the rise of the United States at the close of World War II, the World Bank has remained throughout its history the leading international development organization. Over the years, however, it has been criticized for several problems, including unsustainable development policies,Footnote 1 long project approval times,Footnote 2 and inadequate financing capacity for infrastructure projects.Footnote 3 It has also been associated with intrusive policy conditionality.Footnote 4

In 2016, rising China established the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), with fifty-seven founding members. This new institution joins two dozen multilateral development banks (MDBs) that have been formed since 1944.Footnote 5 Its ostensible goal is to fill a shortfall in infrastructure investment in Asia and beyond.Footnote 6 Yet the AIIB stands out for several reasons: its size and ambition; the absence of the United States and Japan; and, perhaps most importantly, Chinese leadership of the institution. The AIIB might represent real competition for the World Bank and for Western political influence in the developing world.

Of course, the prospect of alternative funding does not necessarily force governments to shift away from the West's foremost development organization. The AIIB has largely aligned its lending standards with those of other MDBs,Footnote 7 and it might simply fit well within the existing MDB complex with little disruption to the World Bank.

Moreover, the World Bank might adapt. Scholars have found that Western donors have scaled back their demands of recipient countries in response to competition.Footnote 8 Perhaps accordingly, Humphrey and Michaelowa find that Chinese foreign aid has not been a “game changer” for World Bank lending.Footnote 9 If anything, Zeitz finds that the World Bank provides a larger share of infrastructure-intensive projects to countries receiving more Chinese aid.Footnote 10

Still, governments dissatisfied with the World Bank may be looking for new options.Footnote 11 To assess this possibility we consider a specific group of developing countries that joined the AIIB: the founding members. In considering the founders, we follow Broz, Zhang, and Wang who emphasize the importance of key countries undertaking costly action to signal their interest in new leadership of the global economy.Footnote 12 They focus on countries that sent high-level delegations to a key summit on China's Belt and Road Initiative. In studying the founding members of the AIIB, we consider a costlier signal. The action constituted no mere summit meeting, but rather the founding of an institution—perhaps a sign that they are looking for alternatives to the World Bank.

For these developing countries that helped found the AIIB, we hypothesize fewer World Bank projects in the area of infrastructure—the specialty of the AIIB. In testing our hypothesis, we pursue an innovative identification strategy, using a recently developed method, the Dynamic Multilevel Latent Factor Model (DM-LFM).Footnote 13 This model serves as an alternative to the difference-in-differences approach when the parallel-trends assumption is violated. Unlike the synthetic control method for comparative case studies, this approach accommodates multiple treated units and also corrects for biases induced by unit-specific time trends. We further analyze the data using difference-in-differences, negative binomial, Poisson, and two-way fixed effects models, as well as the generalized synthetic control (Gsynth) method.Footnote 14 Within the literature on the rise of China, this paper is the first (to our knowledge) to employ this full set of methods, and specifically to use the approach of Pang, Liu, and Xu.Footnote 15

Analyzing data on World Bank projects for 155 recipient countries from 1992 to 2019, we find at least short-run evidence supporting our hypothesis: a drop in participation in World Bank infrastructure programs by the developing founding members of the AIIB. Specifically, we estimate an average reduction of 22 percent in the annual number of new World Bank infrastructure projects in these countries.

Note that while we also estimate a drop in World Bank loan commitments for the founders, the estimated effect is imprecise and lags behind the effect on the number of projects. We can more confidently report a drop in projects. As our interviews suggest, the number of projects better proxies for government interaction with World Bank staff, its cumbersome approval processes, and its intrusive policy conditions.

The estimated effect is attenuated in 2019, suggesting that it may be temporary. Unfortunately, analysis of 2020 data is confounded by the pandemic. Kilby and McWhirter present evidence that World Bank lending follows a distinct pattern in this period.Footnote 16 We leave the investigation of the impact of COVID-19 to future research.

Still, our methodology shows at least a temporary effect through 2019 for the developing AIIB founders. The DM-LFM accounts for both time- and unit-specific treatment and covariate effects, and addresses potential bias due to unobserved time-varying confounders by estimating latent factors. The DM-LFM relies on the key assumption of latent ignorability, which assumes that treatment assignment is ignorable conditional on observed covariates and unobserved latent variables.Footnote 17 Estimates could be biased through a feedback effect, however, if the decision to become AIIB founders and the 2016 establishment of the AIIB were determined by countries’ previous borrowing from the World Bank. To address this possible selection bias, we conduct placebo diagnostics. The estimated negative effect emerges only with the founding of the AIIB in 2016, not before, which furthers confidence in our results.

Our approach does not enable us to distinguish whether the effect is driven by demand (the decisions of the AIIB founders) or supply (the decisions of the World Bank). Our limited interview evidence suggests that the mechanism runs through the demand channel, which is consistent with the bold move of the founders to establish the AIIB.Footnote 18 As for a supply channel, we analyze key dependent variables from the literature—such as US voting behavior on the World Bank executive board, and levels of World Bank conditionality. We find no convincing evidence that the World Bank is punishing the founders. Furthermore, we find an effect of AIIB founding membership only on infrastructure projects, not on non-infrastructure projects—where AIIB founders still rely on World Bank projects because the AIIB has not yet focused on them.Footnote 19

We conclude that the effect we estimate is driven by demand. When it comes to infrastructure, the AIIB founders have begun to turn their backs on the World Bank.

We recognize that this finding could be a result of “crowding out,” if AIIB projects simply replace World Bank projects. But not all the developing AIIB founders actually participated in AIIB projects during our sample period, and, interestingly, our results are not driven by AIIB project participation—the effect holds for both sets of founders. While we expect all the developing founders to draw on AIIB funding eventually, these countries appear to have become emboldened by the founding of the AIIB to distance themselves from the US-led World Bank—some of them even before entering into AIIB projects.

The AIIB founders may have turned away from these World Bank projects as a costly signal to encourage World Bank reforms. On the other hand, they might genuinely prefer China's institution and be willing to forgo the benefits of working with the World Bank to avoid the costs (slow approval and intrusive policy advice) as they look forward to working with the AIIB.Footnote 20

The World Bank and the Founding of the AIIB

The World Bank's largest shareholder, the United States, publicly opposed countries’ joining the AIIB in the run-up to its founding in 2016.Footnote 21 This opposition was perhaps not without reason. Some scholars contend that the very purpose of the AIIB is to supplant the old development institutions—along with the influence of the United States and Japan.Footnote 22 No small operation, the AIIB is often portrayed as “China's World Bank.”Footnote 23 Its president, Jin Liqun, has touted it as a “sophisticated, clean and efficient bank.”Footnote 24

The World Bank is better established, but the AIIB has some advantages. Developing countries have long complained about the World Bank's project approval procedures and extensive social and environmental standards.Footnote 25 The World Bank confesses that “improving the timeliness of lending operations remains a challenge”—the time from concept to first disbursement averages more than two years.Footnote 26 By contrast, the AIIB's average time from concept to approval is a mere seven months,Footnote 27 providing a “lean” and “clean” source of infrastructure financing.Footnote 28

Though still in the early phases, the AIIB has already approved 172 projects, with 34 additional proposals under consideration (at this writing). Total financing for these projects runs into the tens of billions of US dollars. These projects go to more than thirty countries around the world; most are in Asia and the South Pacific, but many are in Eastern Europe, and some in Africa.Footnote 29

AIIB Founding Members

The AIIB has (at this writing) approved membership for 105 countries, including 16 prospective members awaiting domestic approval of their formal membership. The organization is quickly becoming global: of the 89 formal members, 43 are nonregional, and of the prospective members, 11 are nonregional.Footnote 30

This study examines the relationship between the developing AIIB founders and the World Bank. To qualify as founders, governments needed to sign the Articles of Agreement before 2016. Doing so granted them privileges, such as augmented vote shares and participation in nominating AIIB management.Footnote 31

In focusing on AIIB founders, we are influenced by the pathbreaking study of Broz, Zhang, and Wang, who observe, simply, that “leadership, by definition, requires followers.”Footnote 32 In their study of the Belt and Road Initiative, they consider the set of countries that sent high-level government officials to president Xi Jinping's 2017 high-level summit on global economic cooperation. They argue that, because the summit was perceived as an effort to validate a new world order, sending a high-level delegation represented a costly signal of support for China's leadership of the global economy. In their analysis, they find that these supportive countries stand out for the economic hardships they suffered under US leadership of the world economy.

Becoming an AIIB founder similarly signaled an embrace of China's rising status and defied the public preference of the United States. While it is true that the World Bank has slowly adapted to give more voice to emerging markets,Footnote 33 under-represented states are actively seeking alternatives.Footnote 34 Developing countries have finite capacity to take on loans,Footnote 35 and Bunte shows that governments have well-defined preferences, with some governments having a distaste for the strings attached to World Bank loans.Footnote 36 The AIIB brings new borrowing opportunities for countries dissatisfied with Western political dominance over the World Bank.Footnote 37 At the AIIB, decision-making power is concentrated in emerging-market countries,Footnote 38 which prioritize streamlined project approval over cumbersome and intrusive processes.Footnote 39

Data

We seek to test one key hypothesis: a negative effect of AIIB founding membership on World Bank infrastructure projects. Our data set includes 155 countries that participated in at least one World Bank project from 1992 to 2019 (see Appendix F). This set of countries includes some that “graduated” out of eligibility to borrow from the World Bank before 2016, and so we also analyze specifications where we exclude countries classified as high-income (see Appendix A.3.2). The number of countries in the analyses varies due to missing data, and so we further analyze models with imputed data (see Appendix A.2). Our conclusions are robust to these sample variations.

Coding AIIB Founders

Our key explanatory variable takes inspiration from Broz, Zhang, and Wang.Footnote 40 AIIB founding members are listed in Schedule A in the AIIB's Articles of Agreement. We define a developing AIIB founder as one that borrowed from the World Bank during our sample period. This set of countries faced explicit US pressure—their audacity was necessary for the AIIB to come to fruition. Public US opposition subsided after the AIIB was founded, and countries that joined the AIIB later did not face the same pressure as the founders did.Footnote 41

Because it was founded in 2016, we code AIIB Founder × Post-2016 equal to 1 for the years 2016–2019 for AIIB founders, and 0 otherwise. In total, there are fifty-seven founding members of the AIIB; however, some of them are developed countries that did not receive projects during our sample period. Of the 155 countries in our sample that did receive World Bank projects, thirty-one are developing AIIB founders (see Appendix F).

Because five founders drop from the sample due to missing data when covariates are included, we conduct additional analyses with multiple imputation (see Appendix A.2).Footnote 42 Our conclusions hold for both samples, as well as when we exclude high-income developing founders or outliers (see Appendix A.3).

World Bank Infrastructure Projects

Our key dependent variable is the total number of infrastructure projects approved by the World Bank for a given country in a particular year.Footnote 43 We use detailed data on project-level sectoral composition to code infrastructure projects using the Bank's “major sector” categories.Footnote 44 Following Zeitz,Footnote 45 we consider the following as infrastructure sectors: agriculture; energy and extractives; info and communication; transportation; and water/sanitation/waste. Examples of sectors coded as non-infrastructure are education, finance, health, services, administration, and social protection.

For our main analysis, we code a project as “infrastructure” if at least 50 percent of the World Bank's appraisal costs fall into one or more of the previously listed infrastructure sectors (and “non-infrastructure” otherwise). There are alternative ways to classify projects, and we experiment with different thresholds beyond the 50 percent cutoff. We also use the approach of Zeitz, coding projects as infrastructure only if the largest “major sector” is one of those listed before.Footnote 46 Finally, we use a more restrictive definition of “infrastructure,” including only projects where the largest “major sector” is energy and extractives, transportation, or water/sanitation/waste. Our conclusions hold across these coding schemes (see Appendix A.6).

Control Variables

To control for economic development and size, we include GDP per capita and population (both logged), taken from the World Development Indicators.Footnote 47 We further include total debt service as a percentage of gross national income (GNI), net ODA received as a percentage of GNI, and net foreign direct investment inflow as a percentage of GDP, all from the World Bank.Footnote 48 We account for domestic political institutions by including the Polity2 index from the Polity Project.Footnote 49 Research shows that World Bank lending is correlated with national elections in recipient countries,Footnote 50 so we include an indicator variable for lagged executive or legislative elections.Footnote 51 Addressing foreign relations, we control for whether a country is an elected member of the UN Security Council,Footnote 52 and for ideal point affinity with the United States in UN General Assembly voting.Footnote 53

Identification Strategy

Analyzing the effect of AIIB founding membership involves a binary treatment (AIIB founding member) and two periods (pre- and post-2016). Therefore, one should consider using a difference-in-differences model. But this approach relies on an important assumption: parallel trends between treated and untreated observations. While there is no definitive test, inspection reveals that, for our case, the pretreatment trends for the treated and control groups differ, which is often considered indirect evidence of a violation of the parallel-trends assumption.Footnote 54

Our main analysis therefore relies on the DM-LFM.Footnote 55 This model addresses unit-specific time trends, as well as heterogeneous and dynamic relationships between covariates and the outcome. It accommodates multiple treated units and thus also serves as a Bayesian alternative to the synthetic control method for comparative case studies.

Using a Bayesian approach, the DM-LFM approaches causal inference as a problem of missing data on counterfactual outcomes for treated units in the post-treatment period, had they remained in the control condition. The model estimates the average treatment effect on the treated (ATT) based on the posterior distribution of treated counterfactuals. In essence, this method performs a low-rank approximation of the observed untreated outcome matrix to predict the treated counterfactuals in the (T × N) rectangular outcome matrix and incorporates a latent factor form to correct biases caused by the potential correlation between the timing of the treatment and the time-varying latent variables.

The DM-LFM is well-suited to our case. First, it addresses possible bias if the conventional parallel-trends assumption does not hold, relying instead on the more relaxed “latent ignorability” assumption.Footnote 56 Second, compared with the synthetic control method,Footnote 57 which requires a single treated unit, the DM-LFM accommodates multiple treated units. In addition, compared with the frequentist latent factor model Gsynth,Footnote 58 the DM-LFM allows covariate coefficients to vary by both unit and time, and produces more accurate estimates with narrower uncertainty measures.

Still, Pang, Liu, and Xu recommend using multiple methods to triangulate findings,Footnote 59 and we present those methods in Appendix A.1. Our qualitative findings are robust across standard difference-in-differences, negative binomial, Poisson, and fixed effects regressions, as well as Gsynth.

Results

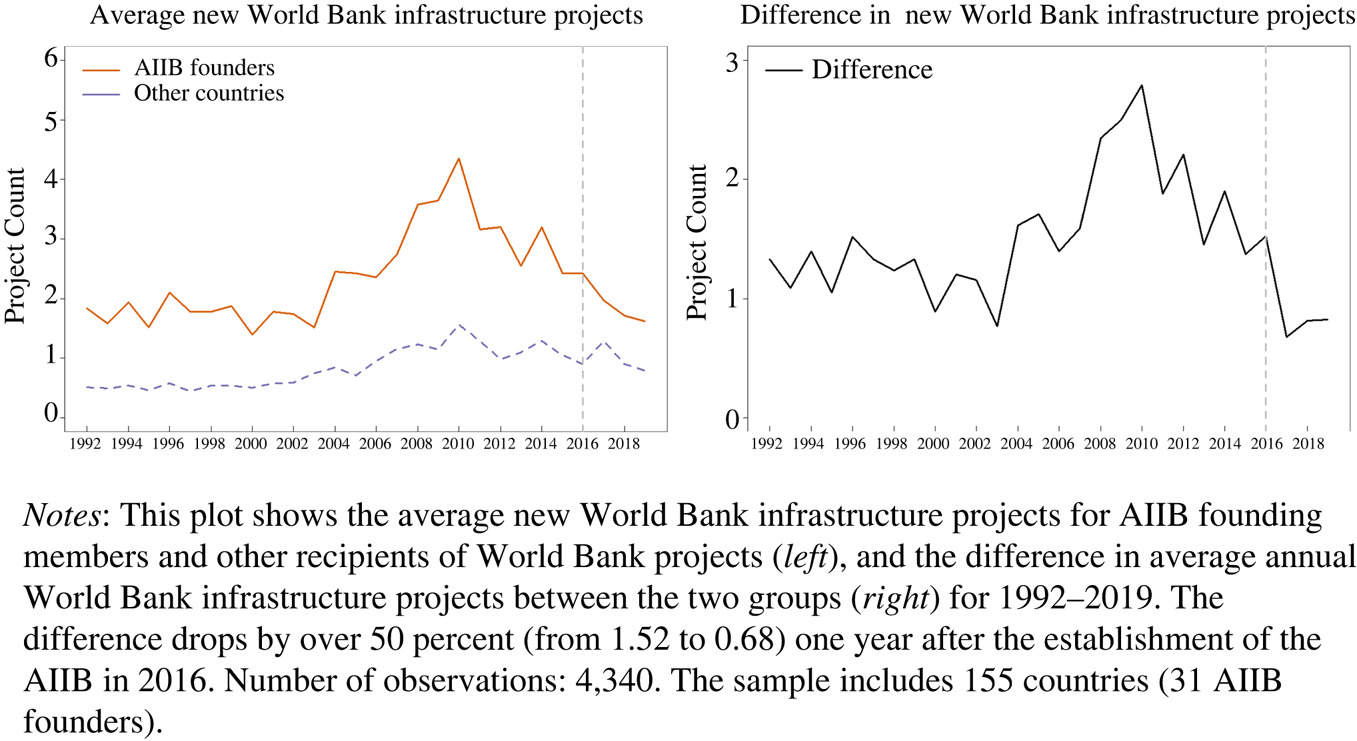

The left panel in Figure 1 shows the annual number of newly approved World Bank infrastructure projects for AIIB founders and other developing countries. Following 2016, there is a drop for AIIB founders, but not for other countries in the sample. The right panel shows the difference between the two sets of countries. On average, the founders participate in more projects than nonfounders. After 2016, however, the difference drops by over 50 percent, from 1.52 in 2016 to 0.68 in 2017.

Figure 1. World Bank infrastructure projects for AIIB founders versus other countries

As the figure shows, the difference in outcomes between treated and control groups varies during the pretreatment period, and the pretreatment trends do not track closely. These patterns suggest that the parallel-trends assumption might not hold. While we further explore the difference-in-differences approach in our robustness checks (Appendix A.1), the DM-LFM is more appropriate here.

The DM-LFM

Table 1 presents the estimated coefficients and credible intervals from the DM-LFM analysis. The dependent variable is the number of World Bank infrastructure projects. The specification presented in column (1) includes only our key explanatory variable, AIIB Founder × Post-2016; column (2) includes our control variables. The 95-percent credible intervals for the treatment coefficients (AIIB Founder × Post-2016) across the models are precisely estimated as negative, in accordance with our hypothesis.

Table 1. The AIIB founder effect on World Bank infrastructure projects

Notes: Results from DM-LFM showing estimated average treatment effect on the treated and invariant component of covariate coefficients βit (see Pang, Liu, and Xu Reference Pang, Liu and Xu2022). Country-year observations for 1992–2019; 95-percent credible intervals in square brackets. Dependent variable: total annual number of new infrastructure projects approved by the World Bank. Country-year level covariates (except for AIIB Founder × Post-2016) lagged by one year.

A more complete presentation of the DM-LFM results requires pictures. Figure 2 presents the average observed outcomes for the treated observations (solid line) along with counterfactual outcomes for treated units, estimated with the DM-LFM (dashed line). The estimated counterfactual outcomes for the treated units are closely in line with the observed outcomes during the pretreatment period. This pattern is a good sign for the appropriateness of the DM-LFM. Note that the observed and counterfactual outcomes diverge—in the expected direction—after treatment begins in 2016.

Figure 2. Estimated counterfactual and actual new World Bank infrastructure projects

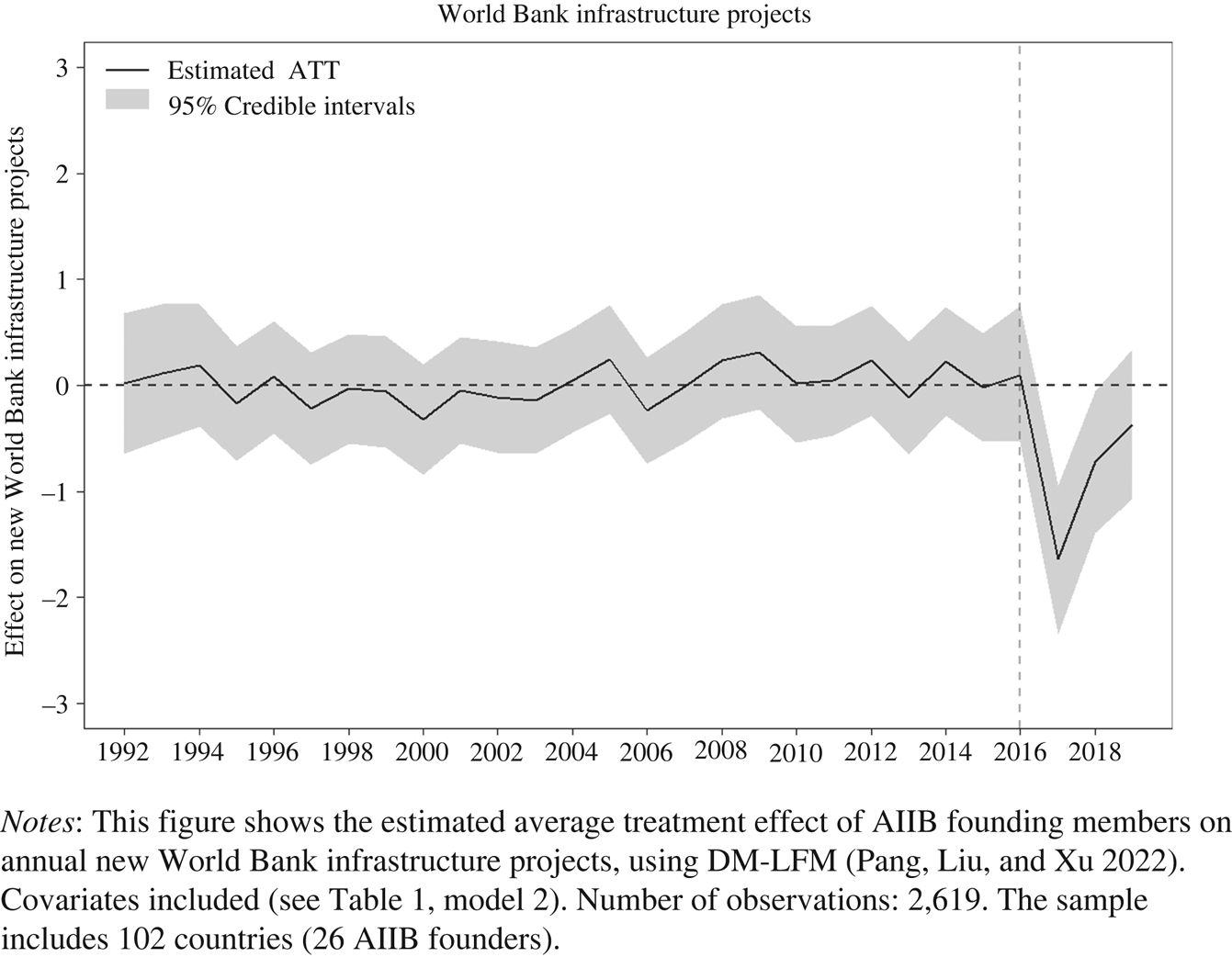

Figure 3 presents the ATT, along with the 95-percent credible interval. The estimated effects during the pretreatment period (1992–2016) are indistinguishable from zero. After 2016 the ATT drops, indicating that AIIB founding members, on average, receive fewer infrastructure projects from the World Bank after the establishment of the AIIB. The negative effect is most pronounced in 2017 and remains, though attenuated, in 2018. The estimated effect for 2019 is also negative, but the 95-percent credible interval includes zero.

Figure 3. Estimated effect of AIIB founding members on new World Bank infrastructure projects

We conclude that the DM-LFM is appropriate for our data, and that the results support our hypothesis. After the establishment of the AIIB, founders receive an annual average of 0.66 fewer infrastructure projects from the World Bank, which represents a drop of about 22 percent.Footnote 60

The finding is robust to various checks, including triangulating with additional regression models, imputation of missing data, excluding outliers, and reclassifying infrastructure projects; see Appendix A.

Selection Bias

The DM-LFM addresses unobserved time-varying confounders by estimating latent factors. But the method relies on a key assumption called latent ignorability, whereby the most critical identification concern is possible feedback. In our case, feedback is a problem if the decision to join the AIIB as founders and the establishment of the AIIB in 2016 are determined by countries’ previous World Bank borrowing.Footnote 61

We thus conduct a “placebo test.” Instead of using the appropriate year of 2016 as the onset of treatment, we use 2014, which was obviously before the establishment and formal operation of the AIIB. This approach sets up a placebo period of 2014–2016 during which we expect weaker or null results.

The results, presented in Appendix B, confirm our expectations. The estimated effects during the placebo period are close to zero. And they are negative starting only in 2016, the year of the founding of the AIIB.Footnote 62

The Supply Side

We contend that the estimated effects are driven by the decisions of developing AIIB founders. They seem to have turned away (at least temporarily) from the US-led World Bank and toward the Chinese-led AIIB. We know that these countries made the costly decision to defy the very public opposition of the United States to the AIIB. Our interview with a senior specialist, stationed in the country office of an AIIB founder, further confirms this notion. In the specialist's view, increasing political connections between the founder and China are indeed leading to “fewer projects with the World Bank, particularly in infrastructure projects.”Footnote 63

It is certainly possible, however, that the effect is also driven by a decision of the World Bank and its major shareholder, the United States, to punish the AIIB founders. Studies show that countries important to the United States are rewarded with better terms from the World Bank, while distant countries are not.Footnote 64

However, in testing for this causal mechanism, we find no convincing evidence. First, we consider US voting behavior on the World Bank executive board. If the United States were seeking to punish AIIB founders, we would expect it to vote against projects proposed for these countries. Yet, we find only mixed and weak evidence that the United States is less likely to support new World Bank project proposals by AIIB founding members after 2016 (see Appendix C.1).

Second, we consider the relationship between AIIB founding membership and non-infrastructure World Bank projects. If the United States were seeking to punish AIIB founders, it would not limit this punishment to infrastructure projects. We would expect a negative effect for non-infrastructure projects as well. But if the mechanism behind our main finding runs through the decision making of developing AIIB founders, we would not expect an effect on non-infrastructure projects. The AIIB concentrated exclusively on infrastructure at its inception, so even founders needed to continue working with the World Bank for their non-infrastructure development needs.Footnote 65 Examining the data, we do not estimate a drop in non-infrastructure projects for developing AIIB founders (see Appendix C.2). The AIIB-founder effect holds only for infrastructure projects.

Lastly, we consider World Bank conditionality. If the United States were seeking to punish AIIB founders for their defiance, we would expect tougher World Bank conditionality for them than for other countries.Footnote 66 Yet we estimate no such effect (if anything, the estimates provide weak evidence that AIIB founders receive lighter conditionality; see Appendix C.3).Footnote 67

Still, we note that while the evidence does not support a “supply-side” story, this might be the result of two countervailing forces.Footnote 68 On the one hand, the United States might want to punish AIIB founders. On the other hand, the World Bank, as a bureaucratic actor, may seek to win back and keep its engagement with these countries.Footnote 69 Our interview with a World Bank specialist stationed in an AIIB-founder country highlights this issue. Facing a declining trend, the World Bank “did try to win back more projects.”Footnote 70

Crowding Out and Loan Commitments

AIIB projects might be “crowding out” similar World Bank projects if founders simply replace World Bank projects with AIIB projects. We test for this with two empirical strategies using data on approved AIIB projects.Footnote 71

First, we compare AIIB founders that have borrowed from the AIIB with founders that have not. The estimated negative effect holds for both sets of founders. See Appendix D.1.

Second, we construct a new “counterfactual” measure of total projects that combines World Bank and AIIB infrastructure projects. This measure assigns AIIB projects as if they were provided by the World Bank. Even with this measure, we estimate a negative effect for founders. This suggests that the founders cut their World Bank interactions without AIIB replacement projects. See Appendix D.2.

To be clear, the future option of working with the AIIB is certainly central to our story. But taking all of the evidence together, the drop in World Bank projects for AIIB founders does not appear to simply be driven by the availability of alternative funding (see Appendix D).Footnote 72 The founders have apparently turned their backs on some World Bank projects, at least temporarily.

With this in mind, we consider the effect of AIIB founding membership on World Bank loan commitments for infrastructure projects (Appendix E.2). The point estimate is negative, but the credible interval includes zero (Table E.2). Looking at the effect over time, the shape follows the negative effect for the number of projects: dropping in 2017 and 2018, attenuated in 2019. But the estimates for each year are imprecise—except for 2018, where the 95-percent credible interval excludes zero (Figure E.1).Footnote 73

So there appears to be some effect on loan commitments, but not one that we can report with confidence. Why, then, do we estimate fewer annual projects more precisely? Our interview with an in-country World Bank specialist suggests two related reasons.Footnote 74

First, loan commitments represent a noisy measure of the interaction between recipient countries and World Bank staff, compared to the number of projects. Commitments are based on uncertain project cost estimates, and it stands to reason that we would estimate less precise effects with a less precise measure.

Perhaps more importantly, however, the number of projects represents a more meaningful measure of recipient governments’ interaction with the World Bank. As we discuss in Appendix E, each additional project involves work with World Bank staff, and these interactions are lengthy, cumbersome, and politically intrusive. If we are correct that AIIB founders are turning away from the World Bank because of long-standing complaints about the institution—its conditionality and long approval times, for example—we would indeed expect more action on the number of projects, which directly proxies for recipient country–World Bank staff interaction.

Our strongest evidence, thus, is that the AIIB founders are cutting back on their interactions with the World Bank, its technical advice, and policy restrictions. World Bank advice is valuable but intrusive. We suspect that the founders prefer the light touch and efficiency promised by China's AIIB.

Conclusion

This research note presents the first systematic evidence that the World Bank is losing ground to China's AIIB. The AIIB may thus represent a challenge to the political influence the United States has enjoyed over developing countries through its leadership at the World Bank. While we do not yet know how long the effect will last, the effect we estimate for 2016–2019 is stark, representing a drop of participation in World Bank infrastructure projects of about 22 percent for the AIIB founders. And we suspect that our findings represent only the tip of the iceberg. We expect many studies to follow showing how international institutions led by China are competing with those of the United States.

Considering previous findings, our results are surprising. That the World Bank is losing to a Chinese-led institution seems to disagree with other recent studies. Recall that Humphrey and Michaelowa find that Chinese foreign aid has not had a big effect on World Bank lending in Africa, and Zeitz finds that the World Bank has reacted to Chinese aid by providing a greater share of infrastructure projects.Footnote 75

However, there are important differences between these studies and ours. First, these studies consider the World Bank's competition with China itself, looking at China's bilateral aid. We focus on the competition between the World Bank and a multilateral institution led by China.

Second, previous studies look for an effect on World Bank lending across all countries, not just the AIIB founders. When it comes to the full set of developing countries, we may not (yet—or ever) detect a negative impact on World Bank lending. The institution is adapting to a new world where it must compete with new alternatives.Footnote 76 It is even possible that the World Bank will win back the AIIB founders before they completely turn away. Perhaps the very point of the AIIB founders’ forgoing World Bank projects is to signal credibly their demand for reform. By playing off both institutions, they can achieve better lending terms.

But it is also possible that, for the set of AIIB founders, the ship has already sailed.Footnote 77 As competition between the rivals intensifies, it will be important to examine whether the United States and World Bank can win back any founders—and which additional countries begin to lean more heavily in favor of Chinese leadership. Cutting-edge research on AIIB loans shows that the institution is targeting countries economically distant from China, granting them privileged access.Footnote 78 So China may use the institution to expand its global influence.

Along these lines, our approach and results fit well with the work of Broz, Zhang, and Wang.Footnote 79 Both studies focus on the countries that appear to be looking for new leadership of the global economy. To identify such countries, both studies focus on “first movers.” Broz, Zhang, and Wang look at the early supporters of China's Belt and Road Initiative; we examine the AIIB founders.

Here too, however, there are important differences. While Broz, Zhang, and Wang explore why some countries are looking for Chinese leadership (treating it as a dependent variable), we investigate an effect of following China's leadership (treating it as an independent variable). Taken together, the studies call for more work—looking, on one hand, at the effects of following the Belt and Road initiative, and, on the other hand, at the determinants of why countries joined the AIIB.

Methodologically, this study also advances the literature on China's rising role in development. We are the first to apply the DM-LFM approach, and we combine it with other well-known methods to better identify causal effects using observational data. While we call for further research into the theoretical mechanisms, we can conclude with a high degree of confidence that we have identified an effect of AIIB founding membership negatively impacting World Bank infrastructure projects, at least in the short run. We see this result in dialogue with the findings of previous studies. Together, the literature is beginning to provide a picture of how the rising presence of China within the development scene will reshape global politics.

Data Availability Statement

Replication files for this research note may be found at <https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/2TC5TK>.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material for this research note is available at <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818322000327>.

Acknowledgments

We thank Zhao Chen, Zhaoyuan Chen, Richard Clark, Brendan Cooley, Axel Dreher, Zhikuo Liu, Ming Lu, Helen Milner, Sayumi Miyano, Layna Mosley, Cleo O'Brien-Udry, Xun Pang, In Young Park, B. Peter Rosendorff, Kenneth Scheve, Austin Strange, James Sundquist, Yiqing Xu, Alexandra Zeitz, Grace Zeng, Zhiwen Zhang, Jiejin Zhu, and Ben Zou for helpful comments on previous drafts, and Zetao Wu for excellent research assistance. We are also grateful for numerous suggestions from participants at the Annual Conference of the Chinese Community of Political Science and International Studies, the CCER Summer Institute, the International Conference of China Development Studies, the Pacific International Politics Speaker Series, the Political Economy of International Organization Seminar, the Political Science Workshop China, and workshops at East China University of Science and Technology, the Fudan Lab for China Development Studies, Princeton University, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai University of International Business and Economics, the University of International Business and Economics, and the Yale University MacMillan International Relations Seminar. We further thank the editors and anonymous reviewers at International Organization.

Funding

Jianzhi Zhao acknowledges financial support from the China National Social Science Foundation (no. 19ZDA072).