1. Introduction

Over almost two decades, a new socio-economic paradigm based on sharing usage and ownership has emerged and permanently changed consumption practices. At one extreme, minimalist lifestyle enthusiasts voluntarily reduced the number of their possessions to a strict minimum in an attempt to adopt a more frugal and sustainable consumption strategy (Dholakia et al Reference Dholakia, Jung and Chowdhry2018; Wilson and Bellezza Reference Wilson and Bellezza2022). Instead of acquiring and accumulating private property, renting and sharing usage has become the norm in the sharing economy since consumers can now conveniently obtain the benefits of ownership without the “burdens of ownership” (e.g. Moeller and Wittkowski Reference Moeller and Wittkowski2010). For example, instead of acquiring and servicing a vehicle and paying parking and insurance fees, one can sign up for a car-sharing membership program like Zipcar and use their fleet of vehicles when needed. One can also sign up to become a member of a peer-to-peer (P2P) platform like Turo and rent a car from another private individual. The recent emergence of a wide range of consumption practices has been framed somewhere between innovative solutions with socio-environmental benefits to issues of the hyper-consumerist culture (Richardson Reference Richardson2015), technology-based disruptions praised for their potential revenues (e.g. PwC 2015) and “neoliberalism on steroids” (Morozov Reference Morozov2013).

One could argue that sharing is nothing new. Local neighborhood-based cooperatives for sharing cars have existed for a long time, and ad hoc practices such as borrowing a car from a friend, giving a ride to the airport to family members or hitchhiking date back several decades. What is new are the technological advances (e.g. the Internet, secure online payment, smartphones, GPS technology, peer-reputation systems, electronic identification and smart-lock systems) that are integrated into online collaborative consumption platforms, which make it easier, more reliable and more efficient to organise such practices. What is also new is that sharing takes place not only within the inner circles of one’s social relationships but also on a global scale, where one can rent a stranger’s possessions. For example, Airbnb is an online platform that facilitates accommodation rentals between private individuals around the globe. Another example is CouchSurfing, which was a nonprofit organisation and an online platform created in 2003 to enable travelers to share locals’ couches—before Airbnb’s launch in 2008. However, in 2012, CouchSurfing became a for-profit business and changed its growth strategy, charging users membership fees and displaying ads on its website. This incorporation upset its (founding) grassroots community.

The nomenclature issue is that ‘[i]n some of the theory and research surrounding “the sharing economy,” sharing is so blurred with traditional marketplace exchanges as to be indistinguishable. Or more accurately, the concepts often remain distinct, but a “sharewashing” effort is made to blur them to the extent that marketplace exchange is touted as sharing’ (Price and Belk Reference Price and Belk2016, 193). These diverse new (and even the older) practices provoke chaotic modifications to business activities and consumer behavior – and ultimately to legal rights.

2. Tensions between sharing and market logics

The sharing economy phenomenon is often depicted as a paradox since practices can be positioned somewhere between ‘true sharing’ and market exchange (Acquier et al Reference Acquier, Daudigeos and Pinkse2017; Belk et al Reference Belk, Eckhardt, Bardhi, Belk, Eckhardt and Bardhi2019a; Eckhardt et al Reference Eckhardt, Houston, Jiang, Lamberton, Rindfleisch and Zervas2019a; Guyader Reference Guyader, Albinsson, Perera and Lawson2024; Habibi et al Reference Habibi, Kim and Laroche2016; Schor et al Reference Schor, Fitzmaurice and Carfagna2016). On the one hand, sharing is defined as pro-social behavior that is non-market-mediated and is based on shared ownership (Belk Reference Belk2010). On the other hand, exchange is defined in the marketing literature as an economic behavior embedded in relationships between buyers and sellers who trade ownership rights (Bagozzi Reference Bagozzi1975; Houston and Gassenheimer Reference Houston and Gassenheimer1987). Analyses of the multiple institutional logics at play in the sharing economy highlight the co-existence and dominance of these two logics (e.g. Geissinger et al Reference Geissinger, Laurell, Oberg, Belk, Eckhardt and Bardhi2019; Grinevich et al Reference Grinevich, Huber, Karataş-Özkan and Yavuz2019; Mair and Reischauer Reference Mair and Reischauer2017; Mont et al Reference Mont, Palgan, Zvolska, Belk, Eckhardt and Bardhi2019; von Richthofen and Fischer Reference von Richthofen, Fischer, Belk, Eckhardt and Bardhi2019). It is neither pure sharing nor pure market exchange but, rather, diverse practices differently situated on a continuum with both logics at play. This results in paradoxical tensions between a pro-social orientation and communal norms on the one hand and a for-profit orientation and market norms on the other hand (Guyader, Reference Guyader, Albinsson, Perera and Lawson2024) – or, as Belk et al (Reference Belk, Eckhardt and Bardhi2019b, 424) put it, ‘the moral economy of small-scale communal sharing versus the far-flung reaches of the market economy.’ Moreover, the maturation of the sharing economy and its inherent paradoxes deserve more attention, particularly when it comes to the transition from ownership-based to access-based consumption, since ‘what has been learned in the early days of the sharing economy may no longer apply as this economic system matures’ (Eckhardt et al Reference Eckhardt, Houston, Jiang, Lamberton, Rindfleisch and Zervas2019b, n/a).

This article continues by presenting a differentiation between sharing economy practices based on collaborative consumption platforms and sharing economy practices based on other, related practices in the circular economy or the collaborative economy. Ultimately, the aim is to improve the understanding of the sharing economy by analysing the paradoxical tensions between the opposing logics of sharing and market exchange, which pertain to how property is owned, rented or borrowed through P2P practices. The paradoxical tensions of the sharing economy are discussed in relation to inclusive and exclusive property, the different relationships and styles among participants and the implementations of platform business models.

3. Sharing economy: a contested phenomenon

Many scholars have noted that the sharing economy phenomenon is closely related to or compounded by other paradigms, such as the ‘circular economy,’ ‘second-hand business models,’ ‘community-based platforms,’ the ‘product-service economy’ and ‘access platforms’ or the “‘on-demand’ (gig) economy (e.g. Acquier et al Reference Acquier, Daudigeos and Pinkse2017; Frenken Reference Frenken2017; Frenken and Schor Reference Frenken and Schor2017; Guyader Reference Guyader2019). Despite growing academic interest, the conceptual definition and understanding of the phenomenon have remained “somewhat messy” (Albinsson and Perera 2018, 6). It has been argued that the ‘renting economy’ or ‘gig economy’ might be better terms for car-sharing and ride-hailing practices (Eckhardt and Bardhi Reference Eckhardt and Bardhi2015; Hern Reference Hern2015; Kessler Reference Kessler2015; Roberts Reference Roberts2015). This is a multi-aspect problem due to several interrelated issues:

1. The sharing economy context relates both to P2P exchanges between people using their own property and to exchanges between a firm’s assets and its customers.

2. P2P exchanges can be provided by either private individuals or trained professionals.

3. Organizations can be for-profit- or nonprofit-oriented.

4. P2P exchanges can involve either a permanent transfer of ownership or only temporal access to property.

5. P2P exchanges based on access can involve money (i.e. renting) or not (i.e. borrowing).

6. Monetary involvement in P2P exchanges can be compensation (i.e. a cost-sharing agreement) or remuneration (i.e. a for-profit agreement).

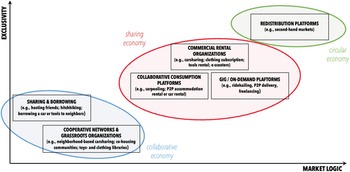

While using the terms interchangeably is understandable in the popular debate as a way to bring in readership, such misleading writing in academic literature reveals a lack of understanding regarding which phenomenon is actually under investigation. Moreover, the debate on contested concept definitions and associated practices is relevant to issues of governance, policy-making, regulations and, ultimately, property rights (Edelman and Geradin Reference Edelman and Geradin2016; Frenken et al Reference Frenken, Meelen, Arets and van de Glind2015; Katz Reference Katz2015; Morgan Reference Morgan2018; Ranchordás Reference Ranchordás2015, Reference Ranchordás2017; Rauch and Schleicher Reference Rauch and Schleicher2015). For example, an Airbnb host offering multiple properties cannot be considered the same as an occasional or amateur host offering a shared space or a private room for rent or to a member of the CouchSurfing community who hosts guests for free. Similarly, an Uber driver who provides a taxi service cannot be regulated in the same way as a carpooling participant can through BlaBlaCar. Confusion about the terms can lead to considering Zipcar, Turo, Airbnb, CouchSuring, Uber, BlaBlaCar, TaskRabbit and eBay as being the same kind of service. It is thus necessary to differentiate these interrelated consumption practices, business models and paradigms. I do so based on (1) the prominence of market logic and (2) the concept of exclusive property (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The sharing economy.

First and foremost, several studies of consumer communities and collaborative practices show that ideologies of solidarity, mutuality, generalized reciprocity and communal belonging co-exist with contrasting ideologies of profit maximization, self-interest and utilitarian motives (e.g. Corciolani and Dalli Reference Corciolani and Dalli2014; Habibi et al Reference Habibi, Kim and Laroche2016; Herbert and Collin-Lachaud Reference Herbert and Collin-Lachaud2017; Martin et al Reference Martin, Upham and Budd2015; Papaoikonomou and Valor Reference Papaoikonomou and Valor2016; Perren and Kozinets Reference Perren and Kozinets2018; Philip et al Reference Philip, Ozanne and Ballantine2015; Prabhat Reference Prabhat2018; Scaraboto Reference Scaraboto2015; Schor et al Reference Schor, Fitzmaurice and Carfagna2016). In essence, the social (communal sharing norms) and economic (market exchange norms) logics of society are becoming blurred such that some practices are more market-oriented than others (Belk et al Reference Belk, Eckhardt, Bardhi, Belk, Eckhardt and Bardhi2019a; Eckhardt et al Reference Eckhardt, Houston, Jiang, Lamberton, Rindfleisch and Zervas2019a; Guyader Reference Guyader2019; Habibi et al Reference Habibi, Kim and Laroche2016).

Second, we can note that the concept of exclusive property, which is about economic benefits, maximizing utility, efficiency, autonomy, independence and the ability to control and decide what can be done with one’s goods (Katz Reference Katz2008), is challenged in the realm of the sharing economy (Kreiczer-Levy Reference Kreiczer-Levy2024; Zhu Reference Zhu2024). Online platforms allow property not only to be bought and owned (i.e. a property right) but also to be easily accessed through borrowing (for free, which makes property more inclusive) or renting (for a fee, which makes it more exclusive).

The following sections clarify the consumption practices, business models and paradigms embedded in the collaborative economy, sharing economy and circular economy.

3.1 The collaborative economy

In the realm of the collaborative economy (Figure 1, bottom left), we find genuine practices of sharing and borrowing, which are nonmonetary (i.e. not market-mediated), unorganized and informal). Examples include hosting friends, hitchhiking, and lending a car or tools to neighbors. These ad hoc practices are the least exclusive and the least embedded in the market logic – in line with Belk’s (Reference Belk2010) conceptualization of sharing. They take place within close social relationships: for example, among friends and family members.

The second type of nonmonetary practices are similar, but they are organized by cooperative networks and grassroots organizations. Examples include other network members (e.g. Warmshowers or CouchSurfing, where platform users offer each other accommodations), neighbourhood-based carsharing (e.g. Majorna Bilkooperativ, a car-sharing cooperative in which members share ownership and usage of the fleet of vehicles), co-housing communities and other forms of shared or fractional ownership (Pasimeni Reference Pasimeni2021) and toys and clothing libraries (e.g. Fritidsbanken or the Toronto Tool Library, which allows local residents to borrow diverse sports and household goods, or Swinga Bazaar, which facilitates the borrowing and lending of household goods and tools among neighborhood residents). These practices, which are facilitated by online and/or offline third parties, are more exclusive than genuine sharing and borrowing among friends and family members in which only members of the platforms or nonprofit organizations can share or borrow properties.

3.2 The sharing economy

Compared with the nonmonetary practices of the collaborative economy, the sharing economy (Fig. 1, center) involves the exchange of money. There are three different ways of obtaining access to property in this paradigm. Online collaborative consumption platforms facilitate the shared utilization and P2P rental of property, such as carpooling drivers and passengers sharing a vehicle for a trip and dividing the associated costs (e.g. BlaBlaCar and Skjutsgruppen), accommodation rentals (e.g., Airbnb), car rentals (e.g. Turo, GetAround) or P2P rentals of household goods (e.g. Peerby and Hygglo). Most platforms charge a commission on successful matches among peer providers (i.e. drivers, hosts and owners) and consumers (i.e. passengers, guests and renters), but some platforms are operated by nonprofit organizations (e.g. Skjutsgruppen).

Online platforms and apps facilitating matches between freelancers or gig workers and consumers of on-demand services are based on the provision of intangible services, such as ride-hailing and on-demand taxi services (e.g. Uber and Heetch), delivery services (e.g. Deliveroo and Instacart) and handyman and moving services (e.g. TaskRabbit). Although not employed by the platforms, these services are provided by professionals (e.g. licensed taxi drivers) who use their own resources (e.g. personal vehicles), unlike collaborative consumption platform users, who are more often amateurs and occasional participants in P2P exchanges. Thus, gig economy practices are more embedded in market logic: peer providers participate to earn money, unlike collaborative consumption practices, whose participants do so to reduce the costs of ownership.

Unlike collaborative consumption and gig economy platforms (i.e. with peer providers), access to property can be obtained from an organization; for example, individuals can sequentially and as needed use a pool of resources owned and managed by a third party, which has more control over how access is provided. Similar to grassroots organizations and cooperatives of the collaborative economy paradigm – but involving money – commercial rental organizations offer access to carsharing (e.g. Zipcar and ShareNow), clothing (e.g. Bag Borrow or Steal), tools (e.g. Home Depot) or e-scooters (e.g. Bird) through rental and membership agreements. These access practices are the most exclusive since customers do not interact but only take turns using the organization’s property – unlike carpooling, for example, where drivers and passengers simultaneously share vehicles.

3.3 The circular economy

In the realm of the circular economy (Fig. 1, top right), we find secondhand markets and redistribution platforms that facilitate a permanent change of ownership (rather than temporary access, as in short-term rentals provided in gig economy platforms, for example) and monetary exchanges (rather than free donations); examples include eBay, Craigslist, Shpock, Depop, Too Good To Go, or Vinted. In essence, individuals can sell and buy each other’s property so that goods are not thrown away (or left unused) but redistributed/recirculated to others who have a need for it. Sellers might not have anybody in their personal networks who wants to buy their goods, so they turn to secondhand platforms to get rid of unwanted possessions. As such, these monetary exchanges do not happen within one’s inner circle (i.e. between friends or family members) but within an outer circle since properties are made available online—and are thus more exclusive. Moreover, P2P sales are monetary exchanges, most of which are embedded in the market logic of e-commerce even though the property is secondhand.

4. Collaborative consumption

The sharing economy is also known as collaborative consumption, which is facilitated by online platforms and which is what this article focuses on, for several reasons. Collaborative consumption practices are the most recent mode of accessing others’ private properties and are the most prominent in the sharing economy. However, they are also the most confusing due to their similarity to commercial rental and to their provision of on-demand gig services which is due to the tendency of some participants to differ strongly (e.g. some Airbnb hosts are experienced hospitality professionals, while others only occasionally host people in their homes), and also due to the fact that some platforms are free to use, but some take hefty commissions. In particular, collaborative consumption is defined by three key characteristics (adapted from Benoit et al., Reference Benoit, Baker, Bolton, Gruber and Kandampully2017):

-

The nature of the exchanges: no ownership transfer, only temporary access to privately owned and underutilized tangible resources (property), which is based on rental business models.

-

The number and type of actors: an online platform provider (e.g. Airbnb), peer providers (e.g. hosts) and consumers (e.g. guests), which forms a triadic relationship.

-

The mode of exchange: market-mediated and -compensated, which uses monetary practices.

Hence, collaborative consumption practices are different from circular economy practices, which are based on redistribution systems and secondhand markets (e.g. eBay) that induce a transfer of ownership and collaborative economy practices that are not market-mediated. Moreover, since collaborative consumption is based on increasing the usage of existing goods (and not on adding new resources to the market), it is different from the gig economy’s on-demand services (e.g. Uber). Eventually, collaborative consumption practices require private individuals to interact with one another, which is different from product-service systems that are based on commercial relationships between a company owning assets (e.g. Zipcar) and customers who do not meet since access occurs repeatedly.

5. Tensions related to the relationship among collaborative consumption participants

The tensions between sharing logic and market logic arise from differences in whether individuals engage in communal relationships with other collaborative consumption participants, considering each other as friends and with expectations of generalized reciprocity, or whether they engage in exchange relationships with other participants, considering each other as impersonal strangers and with expectations of direct tit-for-tat reciprocity so that exchanges are balanced (Bagozzi Reference Bagozzi1975; Clark and Mills Reference Clark and Mills1979; Houston and Gassenheimer Reference Houston and Gassenheimer1987; Sahlins Reference Sahlins1972). People who engage in communal relationships consider others with kindness and even love, are more altruistic and open to cooperation and have values of collectivism and a shared identity – such as exchanges within a community involving social relationships in which actors participate in consumption and production with no direct reciprocity (Clark and Mills Reference Clark and Mills1979, Reference Clark and Mills1993, Reference Clark, Mills, Van Lange, Kruglanski and Higgins2011; Fiske Reference Fiske1992). Basically, such communal relationships are what families, friends, spouses and romantic partners tend to have. True sharing takes place within such communities (Belk Reference Belk2010). In contrast, Clark and Mills (Reference Clark and Mills1979, Reference Clark and Mills1993, Reference Clark, Mills, Van Lange, Kruglanski and Higgins2011) used the term “exchange relationship” to depict the expectation of reciprocation that business partners, acquaintances, and strangers have with each other, symbolizing the logic embedded in markets between buyers and sellers (Bagozzi Reference Bagozzi1975; Houston and Gassenheimer Reference Houston and Gassenheimer1987; Sahlins Reference Sahlins1972).

The distinction between the two logics, however, is not clear. BlaBlaCar, for example, argued that its “trusted community” members rate their level of trust in each other (88%) almost as high as their trust in friends (92%) or family (94%) (Mazzella and Sundararajan Reference Mazzella and Sundararajan2016). This relates to communal relationships rather than to exchange relationships, despite the monetary compensation taking place between carpooling participants. Houston and Gassenheimer (Reference Houston and Gassenheimer1987) emphasized that the contractual terms of exchanges are established based on the common understanding of the reservation price of each party: otherwise, there is no exchange at all if nobody agrees with the reservation price. Schor (Reference Schor2014, 7) argued that collaborative consumption is a kind of ‘stranger sharing’ because it involves personal relationships between strangers. As such, collaborative consumption concerns practices between friends of friends, where the circle of people who can be trusted is further extended to form a large family. In other words, BlaBlaCar and other online platforms that enable users to create a personal profile and rate and review each other after participating in collaborative consumption are designed to remove the impersonal characteristics of market logic (Belk Reference Belk2010; Scaraboto Reference Scaraboto2015) and emphasize sharing logic instead.

One further aspect of collaborative consumption practices is the dual roles that people endorse, which are different for each side of the platform. The dichotomy of roles for collaborative consumption means that platform users have different objectives depending on which side they are on. For example, consumers want access to more choices, to quality, and to cheap offers. Peer providers want the most compensation for their underutilised possessions. Platform managers must balance each side of the platform to provide satisfactory service to both. There is a tendency and a temptation to see collaborative consumption purely through the lens of economic motivation. To increase their user base, platforms that seek to appeal to users’ economic motivations actively encourage this tendency by . This is evident in how platforms structure the exchanges they host. One of GoMore’s recent email campaigns offered car owners a photoshoot to increase rentals, illustrating the market logic of collaborative consumption. Another campaign had the subject line “Four reasons why you should rent your car” and went on to try to convince car owners by listing the economic incentives first. Nevertheless, by including in their commercials images of people engaging in seemingly friendly conversations or laughing out loud while sharing a ride, GoMore communicates the likelihood of making friends among strangers and belonging to a trustworthy and caring community, which powerfully emphasizes the social interactions of collaborative consumption.

Those who own property (e.g. cars) become peer providers, while those who do not own cars are considered consumers. Peer providers of collaborative consumption can consider their participation as a way to compensate for their ownership costs (i.e. a utilitarian motive in line with market logic) or as an altruistic way to offer their underutilized resources for others to use (i.e. sharing logic). Ultimately, this dual emphasis leads platform users to consider themselves to be in a seller–buyer relationship but also to be dealing with friends who are trying to help each other out.

6. Tensions related to platform business models

BlaBlaCar, GoMore and Skjutsgruppen started as nonprofit organizations for carpooling in 2004, 2005, and 2007, respectively. Contrary to Skjutsgruppen, which has remained a nonprofit organization so far, BlaBlaCar and GoMore have adopted a for-profit orientation. Previous research has shown that grassroots movements tend to become commercially oriented, especially in the sharing economy (e.g. Casprini et al Reference Casprini, Di Minin and Paraboschi2019; Martin et al Reference Martin, Upham and Budd2015). In 2011, BlaBlaCar deployed a platform business model based on a commission for each booking. In the same year, GoMore’s founders realized the business opportunity of their project and developed similar functionalities as BlaBlaCar’s; they adopted a platform business model in 2013. Similar to the way in which Zipcar commercialized the previously existing practice of cooperative carsharing, BlaBlaCar and GoMore adopted genuine sharing practices. After both startups considerably improved on notice board websites (which did not have interactive functions) by using some of the “rules of e-commerce” (i.e. online payments, booking systems and peer ratings) in a more efficient online platform for carpooling participants (e.g. search functions similar to those of other transportation services such as the date, the itinerary, the number of seats requested, and of course the price of the rides), the original members of the carpooling community felt betrayed by the commercialization of their practice (Guyader Reference Guyader2018).

Proponents of “true sharing” argue that the sharing economy is born out of communitarian, nonmonetary and nonreciprocal acts and processes (Belk Reference Belk2010; Ozanne and Ballantine Reference Ozanne and Ballantine2010). In opposition to the commercial nature of the contemporary phenomenon, which is based on rental exchanges between private people, participants in genuine sharing initiatives (e.g. borrowing, swapping and donating practices) were motivated by anticapitalistic and anticonsumerist ideologies (Albinsson and Perera Reference Albinsson and Perera2012; Martin and Upham Reference Martin and Upham2016; Ozanne and Ballantine Reference Ozanne and Ballantine2010). This is in line with the critique of capitalism in that the sharing economy has also reduced diverse modes of exchange (e.g. swapping) to market exchange: ‘objectively and subjectively oriented towards the maximization of profit, i.e., (economically) self-interested, it has implicitly defined the other forms of exchange as noneconomic and therefore disinterested’ (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu and Richardson1986, 46). The sharing economy phenomenon may have been born out of the digitalization revolution, but it has abundant origins in grassroots social innovation and the nonprofit sector, which rely on volunteer work and welcoming communities (Martin and Upham Reference Martin and Upham2016; Martin et al Reference Martin, Upham and Budd2015). Many grassroots movements adapted to the growing popularity of new consumption practices, facilitated by digitalization, while seeking to maintain an authentic sharing ethos. They professionalised – and now facilitate collaborative consumption through online platforms and smartphone apps – in exchange of a membership fee or a commission on P2P exchanges, for example, to finance the costs of hosting and running the technological infrastructure. In doing so, they combine the market logic contained in the process used by many commercial platforms with the sharing ethos that has driven their communities thus far.

Nowadays, agreed-upon terms stipulated in a contract between people taking on market roles reinforce market logic over sharing logic. Moreover, a firm’s goal to provide an efficient matchmaking service means that unreliable or low-quality peer providers and consumers should be removed from the platform (e.g. Uber drivers with a reputation score below 4.7 out of 5), which is at odds with the inclusionary and communitarian values of the sharing ethos that were at the roots of collaborative consumption. Despite being often emphasised in marketing communications (GoMore’s campaign mentioned earlier), collaborative consumption participants may well be disappointed by the claimed social transformation commitment and the social connections potentially created with strangers, as online platforms can fail to create strong social ties, long-term friendships and communal belonging (Schor Reference Schor2014). Platforms intending to facilitate meaningful interactions and social connections among people and to create feelings of communal belonging contradict the goal of globally extending their activities. Moreover, organizations with the stated goal of local community building can be at odds with the necessity of quickly acquiring and maintaining a critical mass of users for online platforms, as demanded by their venture capital funders.

In conclusion, carsharing, carpooling, and P2P car rental have their origins in older practices that once took place outside of the market and within grassroots movements or nonprofit cooperatives (i.e. without commercial orientation and sometimes even employing nonmonetary practices). To differentiate the practice of carpooling (e.g. BlaBlaCar – a collaborative consumption practice) from the professional activity of offering rides that drivers make a profit from (e.g. Uber–gig economy service), some governments have limited the maximum compensation per kilometer that one can obtain from carpooling (e.g. France at 0.06€; Sweden at 0.19€); others have banned ride-hailing or short-term accommodation rental platforms from operating in certain cities (e.g. Uber in Brussels, Belgium; Airbnb rooms in Barcelona, Spain) while others collaborate with these firms on issues such as tax collection (i.e. France and the UK). The question of whether to preserve the past or to favor the future, or both, leads to tensions between slowing down the digital revolution that online platforms engage with (without missing out on opportunities) and promoting the evolutionary adaptation of existing infrastructures to recent technological developments.

7. Tensions related to participation styles/nuances

Different styles of collaborative consumption (e.g. in the carpooling context) illustrate the tensions among the different ways people participate in the same practice (Guyader Reference Guyader2018). The communal style is embedded in the sharing logic: collaborative consumption participants have a pro-social orientation; they value the community to which they feel they belong (i.e. the grassroots movement); and they resent the capitalist ideology embedded in the technological improvements of the platform that lead to a professionalisation of the practice. There is a sort of “us vs. them” (McArthur Reference McArthur2015) situation, where “us” are experienced users (communal style) who were sharing rides before BlaBlaCar improved the overall organisation of the carpooling practice and “them” are the newcomers (consumerist and opportunistic styles) who adopt collaborative consumption as the most fashionable and convenient alternative for an access lifestyle (Rifkin Reference Rifkin2000). The consumerist and opportunistic styles are situated closer to market exchange than they are to sharing (see Figure 2). These two styles emphasize the commercial orientation that paying for collaborative consumption entails. Platform users enacting a consumerist or opportunistic style of collaborative consumption would participate in an apparently contradictory way to platform users who enact a communal style. A study by Klein et al (Reference Klein, Merfeld, Wilhelms, Falk and Henkel2022) showed that some people (“prosumers”) purposely acquire property (e.g. they buy a car); they use it but also capitalize on their ownership by providing others with access to that asset for a fee (e.g. they rent it out). These prosumers even choose which property to acquire, based not only on their own preferences but also on what their peers would like (e.g. particular car brands).

Figure 2. Positioning collaborative consumption styles (based on Guyader Reference Guyader2018).

It is possible to extrapolate the practice styles to organizations facilitating collaborative consumption, where those with historically anticapitalistic communities are formed around nonmonetary practices (e.g. Couchsurfing) close to the sharing ethos, in contrast to the market logic of new Big Sharing startups that are disrupting industry incumbents with new technology (e.g. Uber’s “Be your own boss” campaign). However, the collaborative consumption participants’ style can be at odds with the firms that provide the platform they use. As mentioned earlier, participants in the original carpooling practice (i.e. the communal style) felt betrayed by BlaBlaCar’s change of business model and did not share the same vision that the firm had for them (i.e. a consumerist style of collaborative consumption).

8. Tensions related to inclusive and exclusive property

Earlier examples from the shared mobility sector highlighted the role that platforms play in structuring the arrangements of property rights (i.e. BlaBlaCar turned empty seats, traditionally shared inclusively with one’s inner circle of friends, family members, or co-workers, into an exclusive property on sale on the company’s website) and institutionalizing and uniformizing collaborative consumption practices to a certain extent through rules and guidelines for platform users (e.g. BlaBlaCar’s booking and payment systems), which also determines the autonomy with which collaborative consumption participants can perform a practice (as illustrated by Morgan in this issue).

First, the tensions embedded within the sharing economy between inclusive and exclusive property revolve around the divergent motivations and outcomes for property owners and participants. On the one hand, renting goods owned by others enables a “non-ownership,” a liquid or minimalist lifestyle for consumers who rent property only when needed, and alleviates the burdens of ownership (e.g. maintenance). On the other hand, owning property enables peer providers to cover the costs of ownership so that owning property becomes an affordable and convenient advantage. Indeed, sharing platforms offer property owners unprecedented opportunities for monetization by transforming their assets into lucrative sources of income. For instance, individuals can capitalize on their idle resources, such as spare rooms or vehicles, by renting them out to strangers through platforms like Airbnb or Turo. This shift towards exclusive property ownership emphasizes maximizing one’s economic gains and autonomy over one’s assets. However, this comes at the expense of the more inclusive, community-oriented practices of sharing, where property is lent or borrowed within close social circles without monetary exchange. The rise of the sharing economy introduced a competitive dynamic of property, where individuals must choose between maximizing financial returns or fostering community and mutual support.

Second, from the perspective of collaborative consumption platform managers, navigating these tensions requires careful consideration of the balance between inclusive and exclusive property models. Sharing economy businesses must grapple with the ethical implications of facilitating transactions that prioritize monetary gains over communal sharing. Additionally, they face the challenge of maintaining the trust and integrity of their communities in the face of commercialisation.

Third, striking a balance between inclusive and exclusive property paradigms involves implementing policies and features that support both economic sustainability and social cohesion. This may entail offering alternative models of engagement, such as community-focused initiatives or incentive structures that reward nonmonetary forms of exchange. Ultimately, the success of collaborative consumption platforms hinges on their ability to mediate between the competing logics of sharing and market exchange, as well as the notions of exclusive and inclusive property, to ensure that the benefits of sharing/renting are not overshadowed by the pursuit of exclusive property ownership for all.

9. Conclusion

Eckhardt and Bardhi (Reference Eckhardt and Bardhi2015) were among the first to point out that ‘“sharing” is just a fancy word for “rental” (Fournier et al Reference Fournier, Eckhardt and Bardhi2013, 2702) and that ‘the Sharing Economy isn’t about sharing at all.’ While academics argued over the definitional issues and boundaries of the phenomenon (Eckhardt et al Reference Eckhardt, Houston, Jiang, Lamberton, Rindfleisch and Zervas2019a), several voices in the popular debate ‘were raised against the “we-washing,” “co-washing,” or “share-washing”’ communication practices of commercial rental organisations and gig economy platforms. Sharing economy platforms have brought on the monetisation of resources that were previously outside of a market (e.g. personal cars and homes), with business models based on matching people ‘who offer services and others who are looking for them, thereby embedding extractive processes into social interactions’ (Scholz Reference Scholz2016, 4) (see also Belk Reference Belk2014; Slee Reference Slee2015). Some participants are prosocial: they consider their peers to be friends they can trust, and they are focused on the intrinsic value of their involvement – as ‘homo cooperans’ (De Moor Reference De Moor2013; Filippova et al Reference Filippova, Berlingen and Gauthey2015). Others participate because they can maximise their personal outcomes and because they are focused on the extrinsic value of their involvement α as self-interested homo economicus (Eckhardt and Bardhi Reference Eckhardt and Bardhi2016).

In summary, the for-profit market mindset has taken over the original sharing ethos in collaborative consumption practices. However, pro-social aspects are essential to P2P exchanges. While sharing logic and market logic make sense in isolation, their juxtaposition in the sharing economy results in contradictions and difficulties in the conceptualisation of the phenomenon – in line with paradox theory (Poole and van de Ven Reference Poole and van de Ven1989; Smith and Lewis Reference Smith and Lewis2011). This is why the concept of collaborative consumption cannot be anchored either to sharing or to market logic, but it is better to appreciate both logics simultaneously in order to grasp the complexity of the phenomenon in its entirety. It is these characteristics of contradictory but simultaneous logics (e.g. Lounsbury and Boxenbaum Reference Lounsbury and Boxenbaum2013; Lounsbury et al Reference Lounsbury, William and Thornton2012), the diversity of stakeholders and the interdependency of tensions that engender the persistence of collaborative consumption as a paradox (Guyader Reference Guyader, Albinsson, Perera and Lawson2024). Contradictions lie at the foundations of paradoxical tensions. Moreover, paradoxes incorporate features of irony, as tensions create ‘incongruity between what is expected and what occurs or saying one thing and meaning the opposite’ (Putnam et al Reference Putnam, Fairhurst and Banghart2016, 67). Because irony is a way to cope with absurd contradictions (Putnam et al Reference Putnam, Fairhurst and Banghart2016), it is no surprise that the collaborative consumption phenomenon was dubbed the oxymoron ‘sharing economy.’