2025

2025

Beginning with volume 43 (January 2022), the cover of Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology (ICHE) has featured art inspired by or reflective of topics within the scope of the journal and their impact on patients, healthcare personnel, and our society. These topics include healthcare-associated infections, antimicrobial resistance, and healthcare epidemiology. The intent is to feature original artwork that has been created by individuals who have a personal connection to one or more of these topics through their clinical work, research, or experience as a patient or an affected patient’s family member, friend, or advocate. The goal is to provide readers with a visual reminder of the human impact of the topics addressed in the journal and the importance of the work being done by those who read or contribute to ICHE and by all who are trying to make healthcare safer through the elimination of healthcare-associated infections.

For more information on how to submit artwork for consideration for a future cover, please click here.

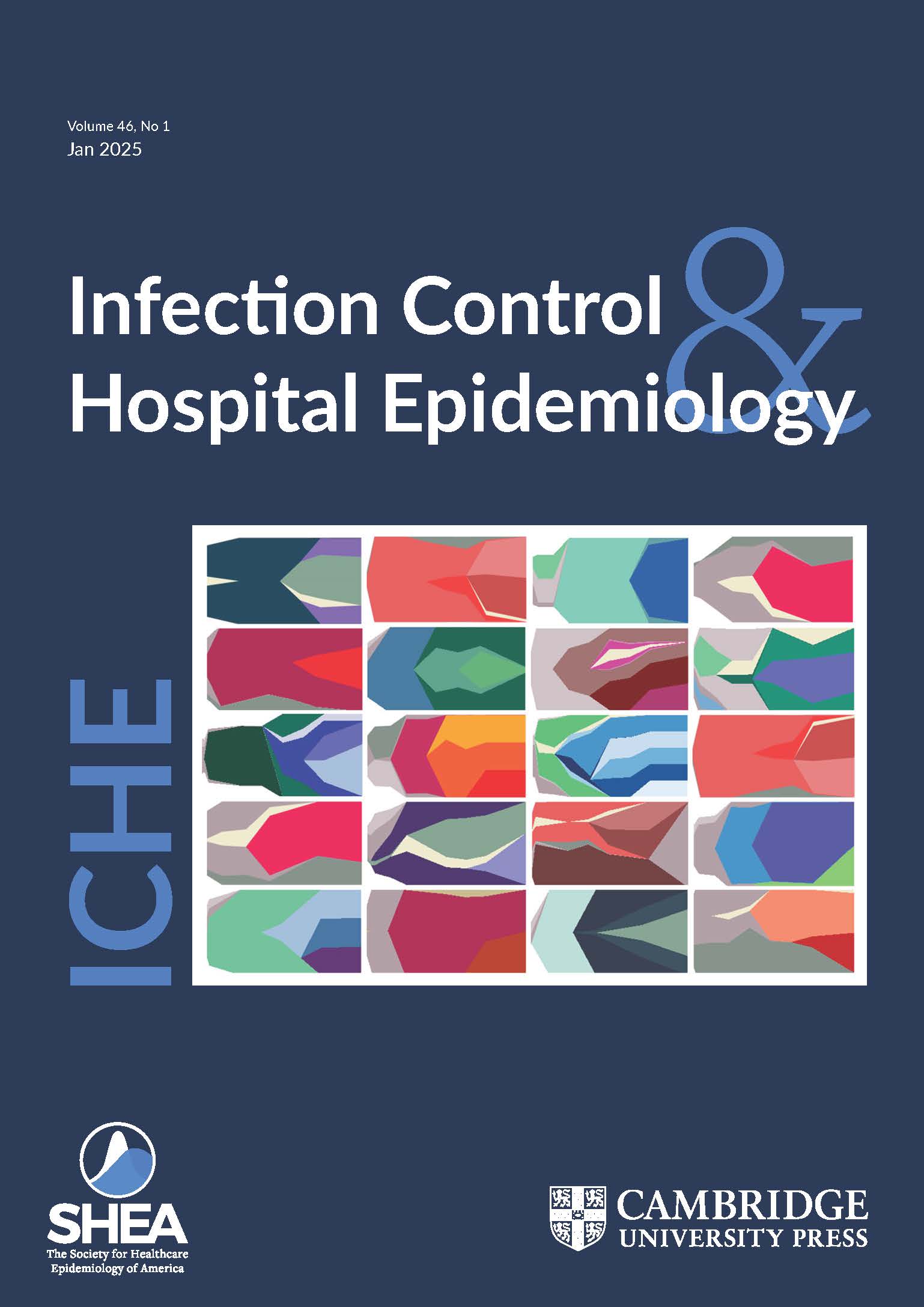

Title: The Dynamics of Bacterial Evolution, 2020

Artist: Angharad Ellen Green, PhD

Medium: The artwork is made up of individual Muller plots representing Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteria lineages that were evolved separately within nasopharynx and lung environments. The command line program muller (v0.6.0 - https://pypi.org/project/muller/), with default parameters applied, was used to produce genotypes and trajectories tables for each of the evolved lineages. These tables were then used as inputs for ggplot2 (v3.3.2) and ggmuller (v0.5.4) in R-Studio (v4.0.2), to produce Muller plots. The individual plots were then assembled to produce the resulting artwork.

Dr. Green spoke to ICHE about her artwork.

What was the inspiration for this artwork?

My postdoctoral research used an in vivo experimental evolution model to understand how Streptococcus pneumoniae (the pneumococcus) adapts to the lung and nasopharynx environments. The pneumococcus was experimentally evolved through a lung infection model and a nasopharynx infection model, producing independently evolved lung and nasopharynx lineages. We sequenced the evolved lineages and compared them to the ancestor to understand how their genomes had changed. This work also enabled us to determine how environmental differences between the upper and lower airways might shape pneumococcal adaptation and evolution. The resulting sequencing dataset was very large and complex with lots of interesting results. I wanted to use an effective method of visualising the data and Muller plots were chosen to display the evolutionary dynamics of mutations found in each evolved lineage over time. In these plots, each mutation is grouped as a genotype, which is represented by a different colour, and the blocks of colour expand when the genetic changes make the bacteria better able to survive in their local conditions. After completing the data analysis and publishing this work, I created this artwork as a memento of my postdoctoral research and I have a canvas of this work hanging in my apartment. Additionally, I wanted to demonstrate how scientific artwork can help visualise the complexities of evolution dynamics and help us to better understand bacterial processes.

What is your personal connection to the content of ICHE?

Throughout my career as a microbiologist, I have carried out research to investigate bacterial pathogenesis and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) of WHO-defined bacterial priority pathogens, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Streptococcus pneumoniae. I have actively promoted the importance of microbial genomic research to confront current global challenges, such as AMR and healthcare-acquired infections. I have championed microbiology research through my various roles in academia, volunteering on the Microbiology Society’s Policy Committee and as a Research Manager at the Healthcare Infection Society. It is an honour for my bacterial evolution artwork to be on the cover of ICHE.

Given the scope of the journal, why is this work appropriate for the cover of Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology?

This artwork is made up of a collection of graphs called Muller plots, which are used to visualize how bacteria evolve when grown in diverse environments. The colours represent genetic changes that have taken place in the presence of environmental factors, such as antimicrobials and the host immune system. The dynamics of evolution are complex and being able to visualise this process enables scientists to better understand bacterial processes, including the development of AMR. This artwork is appropriate for the cover of ICHE as it was created as a direct result of scientific research into how bacteria can adapt and evolve in diverse host niches to cause disease. Additionally, this artwork makes it possible for scientists to visualise the complexities of the dynamics of evolution and comprehend how bacteria adapt to different host environments.

Dr. Green is a Senior Research Data Steward in the Advanced Research Computing Centre (ARC) at UCL in London. Her postdoctoral research at the University of Liverpool was supported by a Sir Henry Dale Fellowship, awarded by the Wellcome Trust and the Royal Society (grant number 204457/Z/16/Z) to Dr. Daniel R Neill. The research from which this artwork was derived was published in Molecular Biology and Evolution (Green AE, Howarth D, Chaguza C, et al. Pneumococcal colonization and virulence factors identified via experimental evolution in infection models. Mol Biol Evol 2023; 38: 2209-2226).

2024

2024

Beginning with volume 43 (January 2022), the cover of Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology (ICHE) has featured art inspired by or reflective of topics within the scope of the journal and their impact on patients, healthcare personnel, and our society. These topics include healthcare-associated infections, antimicrobial resistance, and healthcare epidemiology. The intent is to feature original artwork that has been created by individuals who have a personal connection to one or more of these topics through their clinical work, research, or experience as a patient or an affected patient’s family member, friend, or advocate. The goal is to provide readers with a visual reminder of the human impact of the topics addressed in the journal and the importance of the work being done by those who read or contribute to ICHE and by all who are trying to make healthcare safer through the elimination of healthcare-associated infections.

For more information on how to submit artwork for consideration for a future cover, please click here.

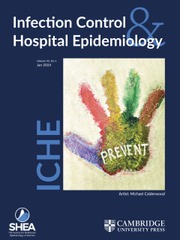

Title: In Our Hands, 2023

Artist: Michael Calderwood, MD, MPH

Medium: Acrylic paints on canvas

Dr. Calderwood spoke to ICHE about his artwork.

What was the inspiration for this artwork?

Over the years, there have been many campaigns to improve hand hygiene in health care facilities (e.g., “Clean Hands Save Lives,” “My Health is in Your Hands,” “Speak up for Clean Hands”). During the past few years, though, the concept of the hand has taken on other meanings, as those in the healthcare community have lent a hand across a myriad of settings, have held the hand of patients, family, friends, and fellow healthcare workers who were suffering, and have stood hand-in-hand in facing the unknown, overcoming obstacles, and navigating the path forward. A hand held in an upward position, as shown in the painting, is also a means of saying “stop” or more specifically “prevent” as written on the palm. Whether it be in areas of HAI prevention, antimicrobial stewardship, outbreak investigation, diagnostic stewardship, or one of the many other topics covered within the pages of ICHE, the idea of prevention is one where safe and effective patient care is front and center in everything that we do. We are strongest when we work together toward a better future, recognizing that we each have something to teach, and we each have something to learn. As for the colors chosen in my art, many of our infection prevention strategies are targeted at infections involving blood, urine, wounds, stool, and water. You will see these each depicted, melding into a singular patina reminding us once again to wash our hands, as clean hands really do save lives.

What is your personal connection to the content of ICHE?

I am an active member of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA), having served on multiple committees, including the Publications Committee. I am both an author and a reviewer for ICHE. Recently, I was lead author on the 2022 update of the surgical site infection prevention section of the Compendium of Strategies to Prevent Healthcare-Associated Infections in Acute Care Hospitals. I have served in leadership roles in hospital epidemiology and antimicrobial stewardship, and I currently oversee both disciplines in my role as Chief Quality Officer at Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center.

Dr. Calderwood is the Chief Quality Officer for Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon, New Hampshire, USA. He is an Associate Professor of Medicine at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth and a staff physician in Infectious Disease & International Health.

2023

2023

Title: Nile’s Joy, Horses & Hope, 2006

Artist: Nile Moss (1990-2006)

Medium: Tissue paper, stained glass technique

Nile’s parents, Carole and Ty Moss, spoke to ICHE about his artwork.

What was the inspiration for this artwork? Nile began every morning with a loud announcement, “It’s going to be such a great day!” At the end of the day, he would jump off the school bus and announce, “I had such a great day!” Nile’s love of horses began very early in life thanks to his school’s participation at a nearby therapeutic riding center. His horses brought him great joy and his faith gave him the hope and promise of a rainbow every day. This piece was inspired by the love Nile had for his horses, Tex and Clutch.

Why is this work appropriate for the cover of Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology?

Nile’s art expression and techniques blossomed from August 2005 to April 2006 in his first high school art class. He returned home with this final creation on April 14, 2006. His life ended only days later when physicians failed to recognize the initial symptoms of sepsis caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) that he had acquired while receiving care in a local hospital. Nile’s story represents the preventable harm that happens when people are unaware and unprepared to protect their loved ones and their patients. Patient safety begins with a robust bench of healthcare professionals, including healthcare epidemiologists, infection preventionists and antimicrobial stewards, that are given the knowledge, tools, training and support they need to do their work effectively. Our healthcare professionals deserve to feel joy and hope at the start of each new day, just as Nile did, and not doubt that their hard work saving lives is appreciated.

What is your personal connection to the content of ICHE?

When Nile died, our lives were changed forever. After researching the “why” and the “how,” we decided to become a part of the solution to end preventable harm in honor of Nile. We became educated on the science of infection prevention to help inform and empower the public and educate healthcare professionals about what happens when healthcare facilities don’t maintain a culture of safety and allow preventable healthcare-associated infections to occur. We celebrate his life every day by empowering the public and healthcare professionals with our story of prevention and action to end preventable healthcare harm.

Carole and Ty Moss are the founders and Executive Directors of Nile’s Project, a non-profit organization founded in 2007 to end unnecessary deaths due to preventable hospital-acquired infections. Nile’s Project works with survivors, families, healthcare professionals, public health officials, and other advocacy groups to increase public awareness and advocate for changes that will make the healthcare system safer. For more information, visit www.nilesproject.com.

2022

2022

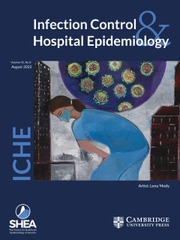

Title: Outsized, Overwhelming Impact of COVID-19, 2020

Artist: Lona Mody, MD, MSc 2020

Medium: Acrylic paints on canvas

Dr. Mody spoke to ICHE about her painting.

What was the inspiration for this artwork?

I am drawn towards color and paint art that conveys the happiness that is in my life. However, COVID changed everything. I had to create something that was wholly different to process this unprecedented historic event. Painting this particular piece was extremely cathartic. It allowed me to reflect on the loss experienced by many, its impact on my peers and come to terms with the fact that the worst was yet to come (I started this work in April of 2020 and completed it in May 2020).

This painting depicts an outsized and overwhelming impact of COVID-19 on our healthcare providers and on our healthcare eco-system in general. I was artistically inspired by the lifeless streets in big capital cities, empty tall haunted buildings and incredible havoc created by a virus that was often depicted paradoxically by vivid colors with precise structures and features. Missing in all these early images was the human factor. With this painting, I wanted to show the immediate and devastating consequences on people that work within healthcare and carry the burden of COVID-19. It is now displayed within our departmental offices as a reminder of our collective experiences.

Why is this work appropriate for the cover of Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology?

ICHE as a journal is about understanding, preventing and controlling infections. It is a journal that publishes high quality evidence written by experts who were overwhelmingly impacted and continue to be impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. This painting also captures the frustration and sadness felt by many of us in this field.

What is your personal connection to the content of ICHE?

Epidemiology, patterns, association, causality always attracted me. Since my residency, I knew that I had to go beyond clinical medicine to understand these concepts. ICHE was the perfect journal that served as an outlet for my research pursuits. In fact, my first paper (borne out of my residency project) was published in ICHE. ICHE has been instrumental in my academic success. Its readership is a community I am most connected with.

Dr. Mody is the Amanda Sanford Hickey Professor of Internal Medicine at the University of Michigan and VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System, Ann Arbor, MI, USA. She directs the Center for Research and Innovations in Special Populations (CRIISP) and is the Associate Division Chief of Geriatric & Palliative Care Medicine, Associate Director of Clinical and Translational Research (Geriatrics Center), and Co-Director of the Medical Arts Program. Her research investigates the clinical and molecular epidemiology of antimicrobial-resistant pathogens and develops novel interventions to prevent them. Dr. Mody is a member of SHEA and an ad hoc reviewer for and frequent contributor to ICHE. She has published 34 papers in ICHE.

2021

2021

Wu Lien-teh, M.D., MPH was born Gnoh Lean Tuck in Malaysia in 1879. His father, who was Chinese, immigrated to Penang to work as a goldsmith. In 1896, Wu won the Queen’s Scholarship allowing him to enroll at Emmanuel College in Cambridge University. After training at St. Mary’s Hospital in London, Wu pursued research at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, the Pasteur Institute, and the Bacteriological Institute of Halle in the fields of bacteriology, malaria, and tetanus. By the age of 24, Dr. Wu was the first student of Chinese descent to graduate from Cambridge with a medical degree.

Dr. Wu returned to Malaysia in 1903, to find that there were no posts in the Medical Service for non-British specialists. After a brief time studying beri-beri, he returned to Penang to establish a medical practice. He advocated for the abolition of gambling, spirits and opium which impacted local government coffers. Wu soon found himself to be in possession of an ounce of opium for which he was prosecuted. In 1907, Wu left Malaysia to accept an invitation to serve as the Vice-Director of Imperial Army Medical College in Tientsin, China.

In 1910, an outbreak of a rapidly fatal respiratory disease occurred in the Chinese-Russian town of Harbin in Manchuria. The outbreak began amongst 10,000 hunters who stayed in crowded inns; they sought marmots for their pelts which, when appropriately dyed, could pass for sable. Wu, being conversant in French and German, was dispatched to work with foreign medical officers. No one had seen pneumonic plague in recent memory, but Dr. Wu strongly suspected the diagnosis and had to overcome Chinese prohibitions against performing postmortems to prove it. With his direction, travel was restricted, plague hospitals were built and the symptomatic isolated, their homes were disinfected, and asymptomatic contacts were identified and quarantined in freight cars. Bodies that could not be buried in the frozen soil were cremated contrary to the teachings of Confucianism. Everyone was encouraged to wear anti-plague masks, the forerunner of the N95 mask. One senior physician who notably refused to wear a mask died of the disease. By the Lunar New Year in 1911, the outbreak had ceased; 60,000 inhabitants had died.

Dr. Wu was nominated for the Nobel Prize for his work as a plague fighter; he directed the National Quarantine Service and was the first president of the China Medical Society. He also championed the modernization of Chinese Medical and Public Health Systems. After the Japanese occupation of China in 1937, he returned to Malaysia where he practiced medicine until retirement at the age of 80. Dr. Wu Lien-teh died on January 20, 1960 following a stroke.

2020

2020

Sir John Pringle (1707–1782) was born into a prominent Scottish family. He initially studied the classics and philosophy followed by 1 year of medical study at the University of Edinburgh. He planned to leave medicine for a mercantile career. While in the Netherlands, Pringle met Boerhaave, and his interest in medicine was re-energized. He received his medical degree in 1730 from the University of Leyden. In 1734, he assumed a chair in the Faculty of Arts in “Pneumatical and Ethical Philosophy” and practiced medicine at the University of Edinburgh.

At the age of 35, Pringle was appointed surgeon to the British Forces, which had formed an alliance with the Habsburg Dynasty against France. In 1745, as Physician General of the Army, Pringle played a role in assuring the humane treatment of prisoners of war and neutrality for military hospitals hundreds of years before the Geneva Convention and the formation of the Red Cross.

In 1748, Pringle returned to London and published his experiences in military hospitals. He recognized that hospital fever and jail fever were spread from person to person and that both syndromes were due to typhus. He mandated that prisoners be washed, that their clothing burnt, and that clean clothes be provided at public expense. He understood that hospitals were a major cause of patient sickness: crowding, filth, and lack of hygiene facilitated the spread of disease. Decades before Florence Nightingale, Pringle advocated for fresh air, cleanliness, and hygiene. He observed that fomites contaminated with body fluids, like bedding, spread sepsis. He adopted microscopy and understood that the mites he saw caused scabies. Many years before Lister and Semmelweis, Pringle used acids and distilled spirits to reduce the spread of sepsis, and the first use of the term “antisepsis” was attributed to him.

During his lifetime, Pringle was recognized for his work as President of the Royal College of Physicians (RCP), Member of the Academy of Sciences, and receipt of the prestigious Copley Gold Medal. He was made a Baronet in 1766 and physician to the King in 1774. By 1780, he retired from medicine and returned to Scotland, but the cold climate did not agree with him. Pringle returned to London, but not before he gifted 10 volumes of his Medical and Physical Observations to the RCP (Edinburgh) with the understanding that they would never be published or lent out. He died 4 months later.

The major advances in infection control that Pringle made to the field have too often been attributed to others, and few reminders of him survive to this day. His birthplace was demolished and his grave destroyed during World War II; 2 paintings remain. A memorial to Sir John Pringle can be found in Westminster Abbey albeit in Poets’ Corner; this location is ironic, as one friend noted that an inadequate appreciation of English poetry was one of Pringle’s few failings.

2019

2019

Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon or Moses Maimonides (son of Maimon) was born in Cordoba, Spain, a center of intellectual and religious freedom, on March 30, circa 1135. Maimon ben Joseph, his father, was a prominent scholar, writer, and judge for Jewish religious courts. Maimonides studied with Averroes, a prominent physician-philosopher. In 1148, his family left Cordoba after a repressive dynasty, the Almohades Caliphate that ruled in Spain and North Africa during the 12th and 13th centuries, required that they either convert to Islam, emigrate, or be put to death. They wandered first to Fez, Morocco, and to Acco, Palestine, before finally settling in Old Cairo (Fostat), Egypt, circa 1165. His father and brother established a business selling precious stones, but soon after, his father died and his brother David perished in a shipwreck. Maimonides turned to medicine as a means to support both families. While only in his thirties, Maimonides was appointed as physician to the Court of the Sultan, and he served as head of the Jewish community in Cairo. During the Crusades, Maimonides’reputation as a healer was so great that King Richard the Lionhearted offered him a position as his personal physician.

Maimonides wrote many scholarly works on a variety of subjects ranging from biblical and Talmudic law to logic, science, and medicine. He embraced the use of careful scientific reasoning and eschewed mysticism. In his 10 books on medicine, Maimonides was an early advocate for the importance of hygiene, bathing, and the need for fresh air, clean water, a healthy diet, as well as proper disposal of refuse and placement of toilets far away from living quarters. Maimonides was an early “steward” who recommended nonpharmacological interventions first. He also noted where evidence was lacking and further investigation was needed before recommendations could be made. Many of the concerns and observations that Maimonides made more than 800 years ago remain highly relevant to the field of infection prevention and control today.

Maimonides died in Cairo on December 13, 1204 at the age of 69. Several legends are ascribed to Maimonides. It is unlikely that he wrote the Oath or Prayer of Maimonides. He is buried in Tiberias, Palestine, on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee in present-day Israel. However, this site was not chosen at random by a donkey that roamed free while bearing his body; Maimonides was interred at Tiberias at his request. Even today, Maimonides remains a highly regarded physician, philosopher, and scholar among Jewish, Arabic, and Christian circles.

2018

2018

John Snow (1813–1858) was 1 of 9 children born to a working-class family in York, England. At the age of 14, he was apprenticed as a surgeon-apothecary with a family friend in Newcastle. He was sent to tend the afflicted in a nearby mining town during a cholera outbreak in 1832. He pursued his medical degree at the university of London, with the sponsorship of a wealthy uncle, and he initially set up a general practice in Soho. He gained fame as a practitioner of the new discipline of anasthesia and tended to Queen Victoria during the births of her children.

On August 24, 1854, a baby died of cholera on Broad Street near Soho. Shortly thereafter, 700 deaths from cholera occurred within a radius of 250 yards, and Snow happened to live nearby. As an anesthetist, he recognized how gases dissipated, and he rejected the prevailing dogma that cholera was spread through the inhalation of atmospheric vapors from decaying material because it would not explain how patients were affected miles away from the source. Snow hypothesized that water, contaminated with some cholera agent in feces, was the more likely explanation.

Using epidemiological principles, he identified who was affected using death certificates and where the illness was acquired (e.g., where case patients lived), then he determined what water supply they had used. He discovered that most households with a cholera case obtained water from the Broad Street pump. Snow ordered that the pump handle be removed. A local curate, Henry Whitehead, initially sought to disprove Snow’s suspicions through further surveillance. Instead, Whitehead found that 8-fold more case patients had drunk from the pump than had not. Furthermore, he revealed that deaths occurred more often among residents who resided closest to the pump than in houses located farther away or that used a different water source. Ultimately, a leak between the Broad Street pump and a neighboring cesspool was discovered.

John Snow continued to carefully study the relationship between water contamination and cholera. Unfortunately, his work in epidemiology was ignored or pilloried in editorials in major journals. Snow would not live long enough to be recognized as a founder of modern epidemiology; he died of “apoplexy”or stroke at the age of 45 years. The John Snow Inn and a replica of the Broad Street pump can still be found in what is now called Broadwick Street in Soho, central London.

2017

2017

Joseph Lister (1827–1912) was born to a Quaker family in the outskirts of London. His father, Joseph Jackson Lister, worked as a wine merchant by day and pursued the study of optics as a hobby. His work helped found modern microscopy, for which he was elected to the Royal Academy in 1832.

Young Lister decided to become a surgeon at an early age. Due to his religious affiliation,Lister was barred from attending older universities of greater prestige and settled upon study at the University of London, from which he received his medical degree and Fellowship in the Royal Academy of Surgeons. Lister moved to Edinburgh in 1853 to work under Mr. Syme, one of the preeminent British surgeons of the day. In Edinburgh, Lister made important observations on the pathogenesis of inflammation. He also gained a wife, Syme’s daughter, Agnes, but in doing so had to become a member of the Church of England. Agnes worked closely beside Lister for many years, recording his experiments in great detail.

By 1856, Lister assumed professorship in surgery at the University of Glasgow, where he began to develop his principles ofantiseptic surgery. At the time, surgical morality rates from sepsis ranged from 23% to 60%, and it was assumed that putrefaction and purulent infection of wounds originated from tainted air. Based on the work of his colleague, Louis Pasteur, Lister performed a series of meticulous experiments in which he used antiseptics and developed optimal wound dressing techniques that focused on keeping wounds clean rather than excluding air. Lister traveled widely in the United Kingdom, Europe, and the United States promoting his wound-care techniques. He returned briefly to Edinburgh before assuming the Chair of Clinical Surgery at King’s College in London. In 1891, Lister became a Founder of the British Institute for Preventive Medicine, the first academic medical research institute in the United Kingdom. He served as the Institute’s President, and the organization was ultimately renamed in his honor. Lister served as President of the Royal Society of London and was appointed to the House of Lords. After his death, Lord Lister chose not to be buried in Westminster Abbey but rather was laid to rest next to his wife.

2016

2016

Florence Nightingale (1820–1910) was named after the Italian city where she was born to affluent and well-educated English landowners. As a middle-class woman in Victorian England, Florence recognized that she was destined for a life of domesticity and “trivial occupations.” Her choice of nursing, given its reputation at the time as a vocation for poor elderly spinsters, was met with significant familial opposition. During her European travels, Ms. Nightingale visited the Deaconess Mutterhaus in Kaiserswerth, Düsseldorf, one of the most forward thinking nursing training schools of the day. She returned to Düsseldorf to complete her training and then studied with the Sisters of Charity in Paris. She later assumed the role of superintendent at a hospital for invalid gentlewomen in London.

In 1854, the Minister of War invited Ms. Nightingale to oversee the introduction of nurses at British Army hospitals in Scutari, Turkey. Up to that point, 20% of men who fought in the Crimean War died, and approximately 70% of those deaths were due to infections such as typhus, cholera, typhoid, and dysentery. The germ theory of disease had not yet been formulated, but Florence Nightingale recognized that most problems were caused by “inadequate diet, dirt, and drains.” She adopted the concept of “sanitary nursing” ensuring that patient care focused on prevention of infection through adequate diet, fresh air, light, warmth, and cleanliness. She was an early advocate for hand hygiene and the need for clean water, adequate ventilation, and appropriate sewage disposal. Each night, she traveled through more than 6 km of hospital wards carrying a Turkish lamp; thus the media referred to her as “The Lady with the Lamp.” With her interventions, mortality rates declined to 2%–6%.

In response, a grateful nation raised £50,000 for the Nightingale Fund, and the first professional training school for nurses at St. Thomas’Hospital, London, was established under her direction. Florence Nightingale was one of the first to apply statistical analysis to her observations. She made important recommendations regarding the optimal design of hospitals and patient wards, saying, “The very first requirement in a hospital is that it should do the sick no harm.” Training schools have been established worldwide based on her ideas. Florence Nightingale was the first woman to receive Britain’s highest civilian decoration, the Order of Merit. She died at the age of 90 after many years of being bed-ridden due to chronic illness, possibly brucellosis.

2015

2015

Ignaz Semmelweiss (1818-1865) was a Hungarian physician who was appointed an assistant inobstetrics at the Allgemeine Krakenhaus in Vienna. He recognized that women delivered by midwife trainees were significantly less likely to die of puerperal fever than those delivered by physicians or medical students. He hypothesized that puerperal fever could be spread to mothers at the time of delivery by the hands of obstetricians that became contaminated while performing autopsies on women who had died in the maternity ward. Controlled trials of hand washing with chloride of lime solution and disinfection of instruments showed that he could reduce infections among the women cared for by physicians by almost 20-fold. Unfortunately, he did not publish his findings which contributed to the lack of acceptance of antisepsis among senior staff; Semmelweiss’ academic appointment was not renewed. He left for Budapest, but his beliefs failed to gain traction among colleagues in Hungary. Semmelweiss’ increasingly erratic and angry behavior led to commitment to an asylum; he died there within a few short weeks at the age of 47 years. Contrary to legend, Semmelweiss’autopsy suggests that he did not die of streptococcal gangrene, but rather of trauma related to beatings inflicted by the guards at the asylum and an early Alzheimer-type dementia.

Starting in 2015, the cover format of each volume of Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology will be changed in order to honor one of many professionals throughout history who not only recognized how disease might be spread, but also how those principles could be applied to reduce healthcare associated infections.