I. Introduction

The European Union (EU) has a longstanding strategic goal of making Europe the world’s most competitive knowledge-based economy.Footnote 1 This goal has led to the continuous search for better regulatory approaches, balancing facilitating innovation with managing the risks of new technologies. Central to these approaches has been encouraging active participation by stakeholders from high-technology sectors (scientists, universities, research organisations, firms, etc.).Footnote 2 New technologies are often subject to deep uncertainties and information asymmetries, which leave authorities with limited information to assess and respond to their risks. Pragmatically, bringing stakeholders into the process of identifying and responding to risks is a means to better access their expert knowledge.Footnote 3 Normatively, greater stakeholder participation can increase the transparency and legitimacy of regulatory responses to new technologies.Footnote 4

In this spirit, in 2020 the Council of the EU recommended the Commission consider the use of regulatory sandboxes. Sandboxes are “concrete frameworks which, by providing a structured context for experimentation, enable where appropriate in a real-world environment the testing of innovative technologies, products, services or approaches … for a limited time and in a limited part of a sector or area under regulatory supervision ensuring that appropriate safeguards are in place”.Footnote 5 The Council argues that sandboxes are “tools for an innovation-friendly, future-proof and resilient regulatory framework that masters disruptive challenges in a digital age”,Footnote 6 and a mechanism for “regulatory learning”Footnote 7 from participating stakeholders. The Commission has already announced that one EU-level sandbox – for blockchain technologies – will launch in 2022.

The Council’s recommendation reflects increasing enthusiasm for sandboxes among Member States. In 2015, the UK Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) launched the world’s first sandbox, designed to facilitate commercialisation of emerging technologies in “fintech” (financial products and services that utilise twenty-first-century technology).Footnote 8 In the FCA’s sandbox, firms apply and, if selected, test their innovative products. They can sell to real customers, without incurring the full gamut of regulation, but on a small scale, for a set period of time and under close supervision.Footnote 9 Through testing, firm and regulator gather more information about the nature, risks and benefits of the product, which may include establishing precise regulatory conditions to apply were it sold commercially.Footnote 10 Based on the FCA’s example, sandboxes have now been implemented in more than fifty jurisdictions, including thirty-two among European Member States.Footnote 11

For a sandbox to be successful, the hosting regulator must attract stakeholders to participate.Footnote 12 Scholarship on existing (sub-)national sandboxes shows agencies often struggle with this task but offers little theory as to why.Footnote 13 Indeed, despite their prevalence, scholarship on sandboxes is limited. Scholars are still at the stage of defining sandboxes in conceptual terms, as instances of – for example – principles-based,Footnote 14 smartFootnote 15 or experimentalFootnote 16 regulation. Empirically, there have been dozens of studies describing sandboxes,Footnote 17 yet few that evaluate their capacity to manage risks,Footnote 18 and very few that have collected primary data from targeted stakeholders.Footnote 19 Further theorising and empirical research are required to better understand sandboxes and when and why they are effective, particularly on the fundamental issue of stakeholder participation.

To that end, this article presents evidence from an explanatory, embedded, single case studyFootnote 20 of the UK’s regulatory sandbox for fintech. The UK’s sandbox is targeted to a particular subset of stakeholders – private firms – and thus the analysis of the case study focuses on regulatory participation by this group. Participation by private firms is a salient issue for regulators supervising innovation. Private firms are often central to the development and diffusion of new technologies and are the primary subjects of regulation thereof. Thus, they can be essential sources of regulatory learning when they choose to participate in regulatory decision-making processes. To investigate their motivations for participation, this case study draws on data from a document study as well as a questionnaire of thirty-six UK fintech firms and qualitative interviews with twenty-one firm senior managers.

Analytically, the case study positions sandboxes within the existing literature on stakeholder participation in regulatory assessments, design and implementation in a European context.Footnote 21 This literature observes that agencies are increasingly inviting stakeholder participation,Footnote 22 but stakeholders often do not respond.Footnote 23 Non-response has been a particularly acute problem for agencies hosting sandboxes because they typically target professional stakeholders (usually firms) in high-technology sectors. Such stakeholders are less likely than those in mature industries to trust regulators and have administrative capacity for participation.Footnote 24 The UK’s regulatory sandbox for fintech, however, has received a large number of applications.Footnote 25

One potential explanation for the UK sandbox’s success is the reputation of its hosting agency. Christopher Woolard, former CEO of the FCA, has said that the agency struggled at first to attract engagement by fintech firms, and only succeeded by improving its reputation with the sector; from “burdensome” and frightening to helpful and “approachable”.Footnote 26 Zetzsche et alFootnote 27 similarly speculate that stakeholders will only be motivated to participate when they perceive the hosting regulator as trustworthy and credible. These anecdotal explanations find support in bureaucratic reputation theory.

Scholars have begun to apply bureaucratic reputation theory to the context of stakeholder regulatory participation in Europe, arguing that agency reputation is an important factor explaining the success or failure of stakeholder participation exercises.Footnote 28 Yet research has focussed on how a regulator’s reputation influences the kind of participation it invites,Footnote 29 paying limited attention to what motivates stakeholders to take up those invitations.Footnote 30 Daniel Carpenter’s studies of US regulators have shown how a regulator’s reputation with stakeholders affects stakeholder motivations as to how they engage with the agency,Footnote 31 but these ideas have rarely been empirically explored in a European context.Footnote 32 Responding to this gap, this study asks: “How does regulator reputation affect stakeholder motivations to apply to regulatory sandboxes?”

This case study finds that fintech firms who want to participate in the sandbox have a range of motivations, prominently to ensure compliance with regulatory requirements and to boost corporate reputation. These motivations are inextricably linked to the FCA’s reputation with the fintech sector as a procedurally correct, high-performing regulator that is morally committed to facilitating innovation.

These findings expand bureaucratic reputation scholarship by beginning to integrate Carpenter’s theory on reputation as a driver of stakeholder engagement with the theory on stakeholder regulatory participation in a European context. The findings illustrate the ways in which bureaucratic reputation likely plays a role in both regulator motivation to “supply” participation opportunities and stakeholder motivation – “demand” – to take up those opportunities.

More practically, the results imply that a regulator’s ability to attract good-quality, good-faith stakeholder participation in regulatory assessments, design and implementation is dependent on its reputation with the targeted sector. EU regulators should thus thoughtfully market themselves and their sandboxes if they want to secure participation from stakeholders in high-technology sectors.Footnote 33

II. Theoretical framing

1. Regulatory sandboxes and stakeholder participation

Regulators often present sandboxes as technical instruments designed to make it easier for innovators to test and commercialise new technologies while managing adherent risks and uncertainties.Footnote 34 Sandboxes, however, are also instruments of stakeholder participation in regulatory assessments, design and implementation.Footnote 35 Sandboxes allow regulators to learn about the risks of emerging technologies and receive immediate feedback on different kinds of regulatory responses, directly from innovators.Footnote 36 Stakeholder participation was a central goal for the FCA’s sandbox. The FCA hoped to “engage with the ecosystem and encourage firms to embrace new ways of doing things in the interests of consumers”,Footnote 37 “facilitating dialogue” through an “open channel of communication”.Footnote 38 The Council of the EU similarly cited the goal of “regulatory learning”.Footnote 39

For this reason, sandboxes can be understood as part of a broader trend of independent regulatory agencies increasingly inviting stakeholder participation in regulatory assessments, design and implementation.Footnote 40 Greater stakeholder regulatory participation can lead to a range of benefits: reduced information asymmetries, more democratic decision-making and the legitimation of regulatory authority.Footnote 41 These benefits, though, are contingent on a number of factors, one of which is attracting enough and the right kind of stakeholder participation. Many stakeholders do not take up regulatory participation opportunities and not all use those opportunities to give substantive input.Footnote 42 Some participate to capture agencies and bias the outcomes of regulatory deliberations.Footnote 43

Indeed, attracting participation from the fintech sector was a challenge that the FCA had to overcome, as it has been for many regulatory agencies.Footnote 44 The FCA’s sandbox, like many sandboxes, targets a particular subgroup of stakeholders: firms. Unlike more mature sectors, fintech lacks a history or institutional structure for routine consultation.Footnote 45 Furthermore, newer fintech firms were often poorly equipped for, and daunted by, the administrative demands of regulatory participation.Footnote 46 Such firms can be especially mistrustful or antagonistic towards regulators intervening in their sector.Footnote 47

Advocates praise the FCA’s sandbox for managing to attract a high rate of stakeholder participation, thus facilitating more sector consultation on the UK’s response to fintech.Footnote 48 Critics, though, attest firms who participate do so in bad faith: to bias regulatory decision-making in order to serve special interests.Footnote 49 This study aims to empirically examine what motivates stakeholders to participate in the FCA’s sandbox, drawing on bureaucratic reputation scholarship.

2. The role of regulatory agency reputation

In bureaucratic reputation theory, reputation is “a set of symbolic beliefs about the unique or separable capacities, roles, and obligations of an organization where those beliefs are embedded in audience networks …”.Footnote 50 Regulators act to build and maintain the kind of reputation that secures capitulation and support from their stakeholder audiences. Audience support increases the agency’s authority, power and influence,Footnote 51 and their autonomy.Footnote 52 Scholars writing on stakeholder regulatory participation in the European context have begun to apply this theory to explain the outcomes of specific participation exercises (eg consultation processes).Footnote 53

Regulators, scholars argue, invite participation not just to gather information, but also to improve their reputation. Regulators want to cultivate support from specific audiences and generally be seen as exercising authority in consultative, democratic, accountable ways.Footnote 54 Different regulators take different approaches to participation. Due to differences in their reputation, some regulators are more incentivised than others to engage in the “persuasion politics” of stakeholder engagementFootnote 55 and to invite certain kinds of stakeholder input over others (eg technical versus procedural input to decision-making).Footnote 56 Thus, reputation influences the outcomes of stakeholder participation exercises by affecting what kinds of participation a regulator is motivated to invite.

This literature, and indeed literature on stakeholder participation in a European context generally, has paid far less attention to why stakeholders take up (or disregard) those invitations.Footnote 57 When discussed, professional stakeholders are usually said to be motivated to participate out of a desire to influence regulatory decision-making.Footnote 58 Broader bureaucratic reputation theory, however, provides a more nuanced account.

Daniel Carpenter’s work, in particular, draws out the varied motivations professional stakeholders – here firms – have for engaging with regulators.Footnote 59 Firms have their own stakeholder audiences, such as consumers and investors. A firm’s actions are motivated by a desire to build the kind of reputation that secures stakeholder support and avoids criticism, attack or resistance to their agenda.Footnote 60 These include how a firm acts towards a given regulatory agency, which is inextricably linked to that agency’s reputation.

The reputation that the regulator has with a firm shapes that firm’s motivations as to how they engage. Those who see the regulator as tough, for instance, are more motivated, out of fear of sanctions, to comply with its demands than those who see it as toothless.Footnote 61 The reputation that a firm thinks the regulator has with third parties, furthermore, shapes how they engage. Firms who believe that the regulator is well-respected by the media, for example, will be more afraid of the damage to their corporate reputation if they defy the agency.Footnote 62

Carpenter’s theory thus implies that regulator reputation shapes what firms think they may stand to lose or gain through regulatory participation. Reputation could affect how many stakeholders respond to invitations, what kind of stakeholders respond, why they respond and how. This aspect of Carpenter’s work, however, has yet to be integrated with theory about the conditions that drive successful stakeholder regulatory participation exercises in a European context.Footnote 63 Indeed, his ideas have only rarely been empirically examined outside US settings.Footnote 64

The goal of this study is to examine what motivates stakeholders to apply for regulatory sandboxes and to explore how these motivations are influenced by the reputation of the hosting regulator. In so doing, this study aims to contribute to building theory on how a regulator’s reputation might motivate stakeholders to take part in regulatory design and implementation in other European regulatory contexts.

3. Analytical approach

This study asks: “How does regulator reputation affect professional stakeholder motivations to apply to regulatory sandboxes?” To address the research question, I first examined what motivations firms report for wanting to apply. Due to the nature of sandboxes, firms may have motivations other than the commonly posited desire to influence policy.

One motivation could be wanting to ensure one’s activities are compliant with regulation. Legal and regulatory risks abound for firms seeking to develop and commercialise novel financial technologies. Finance is a heavily regulated sector. Firms and individuals offering financial services – especially to everyday, non-professional consumers – must hold all appropriate licenses to do so. Even if one holds the right licenses for existing activities, novel kinds of services may require new licenses or new compliance requirements for existing ones. For firms, it is not always clear whether they need a (new) license and what would constitute compliance with that license. This is exacerbated where services are so novel that they were not anticipated in existing regulation and there is still significant legal uncertainty about their status, as was the case – for example – with peer-to-peer lending crowdfunding platforms. Sandboxes provide a means to work directly with the FCA to better understand whether and how a novel service could be compliant with regulation. For some firms, sandboxes are simply a testing ground for discussing potential regulatory issues during product development. For others, sandboxes are effectively an authorisation process. The sandbox test becomes an additional step in earning the licenses required to operate commercially.

Another possible motivation is expedience. Here, firms are less motivated by a desire to be compliant and more by a desire to take advantage of the facilitation services that sandboxes can provide. Most prominent among these is essentially free, bespoke legal advice about how their activities can comply with regulation. These benefits are often not trivial, as some firms would otherwise have to pay significant sums to hire a lawyer or pay a legal firm for advice. A third possible motivation to apply is to boost corporate reputation, as the FCA’s sandbox is highly publicised and may offer positive publicity.Footnote 65

As a final point on participation motivations, sandboxes are, formally, voluntary. Firms can test and commercialise products without the sandbox (as the high rate of non-participation in many jurisdictions attests). Firms can opt to pursue traditional authorisations, adapt their existing authorisations, work under the “umbrella” of another institution’s or individual’s authorisation (either temporarily or by becoming a subsidiary), adapt their product to avoid triggering obvious regulatory requirements or simply bare the legal and regulatory risks (eg see Uber’s strategy of operating in many cities prior to confirming its legal status). Nevertheless, some firms may see the sandbox as their only cost-effective, viable, low-risk option. Worth noting, however, is that the sandbox is also not without costs. Applying for an authorisation has fees, but more importantly sandbox participation bears administrative costs in the form of developing testing plans, reporting during testing and evaluating the test.

Regardless of their motivations, when firms decide whether to participate in sandboxes, they consider the capacities and intentions of the regulator behind it. Not every regulator is equally capable of delivering the benefits of a sandbox, nor do they necessarily intend to.Footnote 66 As firms do not have perfect, objective information on a regulator’s capacity and intentions, Carpenter’s theory implies that they will rely on its reputation.

In deciding whether to apply, firms will be influenced by their impressionistic beliefs about the regulator derived from direct experience, second-hand accounts (eg as industry gossip or media reporting) and other sources.Footnote 67 Regulator reputation is subjective. A regulator will have a somewhat different reputation with different audiences and different individuals.Footnote 68 Reputation does not perfectly reflect reality (eg firms typically overestimate a regulator’s enforcement capacity).Footnote 69 Realistic or not, a regulator’s reputation informs firm decisions about how to engage with the agency.Footnote 70

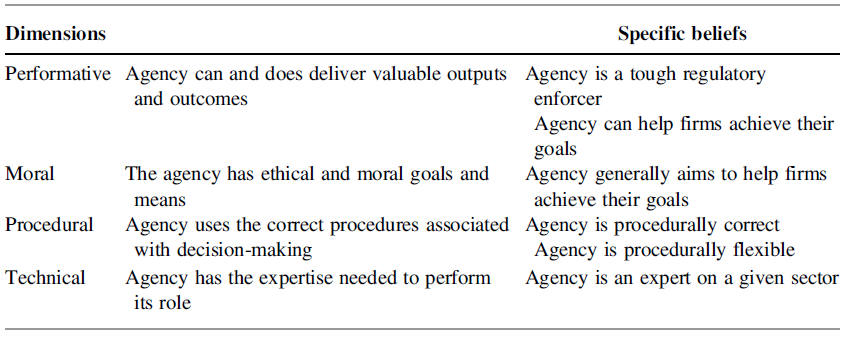

For the case study at hand, then, I examined what reputation the FCA had with the UK fintech sector generally and with each firm individually. Carpenter argues that stakeholders form beliefs about agencies on four dimensions: (1) the quality of agency outputs (performative reputation); (2) its expertise (technical reputation); (3) the normative value of its goals and qualities (moral reputation); and (4) how well it follows required or desirable processes (procedural reputation).Footnote 71 Carpenter’s scholarship further suggests that, within these dimensions, stakeholders form yet more specific beliefs that influence engagement. The relationships between specific beliefs and motivations for engagement are most fully explored in his 2010 study of the US Food and Drug Administration and its supervision of the pharmaceutical sector.

In that study, Carpenter writes that the regulator cultivated a balanced reputation that came to engender from firms both fear and capitulation, but also trust and voluntary engagement and cooperation. On performative reputation, Carpenter observes that a reputation as a “fearsome”Footnote 72 , “intimidating”Footnote 73 “bad cop”Footnote 74 makes firms more afraid of sanctions and therefore more motivated to comply with a regulator’s implicit and explicit demands. Yet regulators must avoid being seen as unreasonably punitive, as this undermines industry trust and goodwill. Relatedly, on moral reputation, firms are motivated to work with regulators that they see as acting in the sector’s interests: as facilitators of industry growth and innovation.Footnote 75 On technical reputation, where regulators come to be seen as the authority on a given sector or technology, this contributes to firms accepting and cooperating with the agency.Footnote 76 On procedural reputation, a reputation for procedural correctness – for applying fair and rigorous administrative processes – similarly drives firms to accept a regulator’s authority as legitimate.Footnote 77 Furthermore, such a reputation makes firms more motivated to act in ways that win the regulator’s approval. Firms want to improve their reputation with such agencies, hoping that the regulator’s approval will increase trust in the firm, thereby reducing scrutiny over firm activities. Receiving approval from a procedurally correct regulator also increases firm credibility with third parties (eg consumers).Footnote 78 Once again, however, in order to maintain industry trust and goodwill, regulators have to balance this with a reputation for procedural flexibility. Firms are more motivated to comply and cooperate – and be “honest” – when they expect the agency not to be unreasonably strict.Footnote 79

The UK fintech sandbox case bears some similarities to Carpenter’s study. Both represent efforts by independent regulatory agencies to supervise the risks of highly technically complex innovations. These contexts, however, are not identical, and I anticipated that reputation might play a somewhat different role in motivating engagement from that which Carpenter describes. In the case study analysis, then, guided by Carpenter, I focused my analysis on the influence that each of the specific beliefs in Table 1 may have on motivations. However, I remained open to different kinds of beliefs and relationships arising inductively.

Table 1. Regulator reputation dimensions and specific beliefs that may influence firm motivations to participate.Footnote 80

III. Data and method

This study employs an explanatory, embedded, single case study.Footnote 81 This case study included: exploratory interviews with FCA staff and industry stakeholders; a document study; a self-administered online questionnaire; and semi-structured, qualitative interviews with fintech firm senior managers.

For the questionnaire and interviews, I created a population frame of 520 UK fintech firms.Footnote 82 All were invited to interview via email. I also engaged in snowball sampling, using the networks of contacts gained through the course of the study. At the time of data collection, approximately 130 firms had or were participating in the sandbox. Some of these companies were not captured by the official population frame as they no longer operated (in the UK), but they were also invited to participate.

Thirty-six respondents answered the questionnaire and twenty-one were interviewed.Footnote 83 While the sample size is small, it offers a rare empirical insight into sandboxes from a firm perspective. The sample is diverse in that respondents come from different sandbox cohorts, subsectors and countries. Fifteen of the interview respondents were current or ex-sandbox and six were seeking/had sought licensing through traditional channels.

I developed a questionnaire and interview schedule. Both ask respondents whether they want to apply for the sandbox and why, as well as what reputation the regulator has with the respondent firm. Questions and codes were replications or adaptations of existing conceptualisations, wherever available (see Appendix 1).

Motivations to apply to the sandbox were conceptualised in two ways: how motivated respondents were to apply and why they were (not) motivated to apply. Respondents were considered to be more motivated when they said they probably or almost certainly would apply in future (assuming eligibility and need). To capture the range of possible reasons why they would apply, I adapted the conceptualisation used in Nielsen and Parker’s study of business motivations for regulatory compliance.Footnote 84

Regulator reputation was conceptualized drawing on Lee and van Ryzin’s Bureaucratic Reputation Scale.Footnote 85 In this scale,Footnote 86 reputation is made up of five dimensions: performative, moral, technical, procedural and “general esteem”. I also asked questionnaire respondents about their specific beliefs about the regulator (see Table 1) and allowed interview respondents to raise other beliefs in an open-ended fashion.

Interview transcripts were analysed in NVivo using qualitative, directed content analysis.Footnote 87 I explored the relationship between different reputational beliefs about the regulator and the extent and nature of motivations to apply. I examined this relationship explicitly by cataloguing the different ways respondents stated that their beliefs influenced their motivations. I also considered more implicit relationships, examining whether certain kinds of beliefs about the regulator were more common among more motivated firms. The questionnaire data were too limited for meaningful linear regression but were used to present descriptive statistics in order to expand on interview findings.

IV. Analysis and findings

1. Professional stakeholder motivations to participate in a sandbox

In interviews, 13/21 firms said they probably or almost certainly would apply. The questionnaire results indicate similarly high motivation (M = 3.46, Median = 3.5, SD = 1.26). Of thirty-six respondents, fourteen said they probably or almost certainly would apply and only five said they probably or certainly would not.

As to why, the most commonly cited reasons from interview respondents were: expedience and making sure they were following the law (13/21 firms cited these motivations). The sandbox was seen by many as “simpler”,Footnote 88 “easier”Footnote 89 and the “quickest”Footnote 90 “fast track”Footnote 91 to “get you to market as soon as possible”Footnote 92 while providing adequate “legal cover”Footnote 93 for a product test and/or commercialisation. Some respondents believed that the sandbox was “the only way to get to market”Footnote 94 because their product was too innovative for a standard authorisation process. Others saw the sandbox as providing “added value”Footnote 95 because the sandbox put firms in a “unique position to get feedback from the FCA”.Footnote 96

The third most commonly cited motivation was to boost corporate reputation (10/21). Nearly half of respondents said they wanted to participate in the sandbox for this reason. Being selected would be a good source of “branding”Footnote 97 and would help put them “on the map”.Footnote 98 Furthermore, fintech firms are novel and exciting, but they can be seen as untested and risky. Many firms hoped that being accepted would show that the firm was “genuine”,Footnote 99 “give comfort” to their customers or “conservative” business partnersFootnote 100 and “prove [to] external validators you’re not just a guy with an idea”.Footnote 101 One respondent argued that the reputational benefits of the sandbox represented the central reason as to why the FCA’s sandbox has attracted so much participation:

[The FCA’s] sandbox was a marketing activity, and this is what every other sandbox missed. There are cohorts in FCA … There is an announcement of who is accepted. It is a cherished element of publicity by start-ups and absolutely gold for a start-up to be included in that list in the cohort. [It] gives us an ability to go to [their business partners] and say: “look this is what we are doing, this is what we are testing with the regulators”. Gives us [a] completely different standing.Footnote 102

No interview respondents explicitly said that they wanted to apply to the sandbox in order to influence regulatory policies to serve their interests. A minority of respondents, however, said that they wanted to participate in order to improve their relationship with the FCA (3/21) and provide information and assistance to the FCA in policymaking (2/21).

For questionnaire respondents, making sure that they were following the letter and spirit of the law was also the most frequent motivation. Nearly half of respondents cited a desire to minimise risks to their customers (16/36). The second most frequent motivation was to be compliant with the law (12/36). Influence was, again, a relatively uncommon motivation (6/36). Contrary to the interview results, however, corporate reputation (8/36) and expedience (6/36) were not as commonly cited. I address these differences in Section V.

2. The role of regulatory reputation in driving participation

a. Performative reputation

Respondents typically believe that the regulator is capable of helping firms like theirs. The majority of interview respondents (16/21) state that their firm sees the regulator as able to help them, and the questionnaire respondents generally share this view (M = 3.69, Median = 4, SD = 0.13). Questionnaire respondents also see the regulator as a tough, capable enforcer of regulatory rules (M = 4.17, Median = 4, SD = 0.79). Interview respondents rarely explicitly discuss the regulator’s enforcement capacity (4/21), but, as will be discussed, they do tend to implicitly hold this belief.

The regulator’s reputation as helpful drove firms to apply out of expedience. A belief that the regulator was able to help was commonly held by firms that were more motivated to apply. Interview respondents explicitly said that they were motivated by a belief that the regulator would be able to expedite the authorisation process and/or offer legal support and resources. One respondent recalled becoming motivated after reading another fintech’s blog about how much the FCA had helped during their sandbox.

[I] looked at some of the previous experiences and it seemed really, really positive. The reasons we went ahead with it was [sic] based on … a case study online. It just showed how the interaction with the FCA was really positive. And I wanted that.Footnote 103

The regulator’s reputation as a tough enforcer, however, was not discussed by respondents as motivating their application. This is surprising, as the regulator is commonly seen as a tough enforcer and complying with regulation was the most commonly cited motivation to apply. One would thus expect firms are motivated, in part, out of fear that the FCA will otherwise sanction their unlicensed testing or commercial operations. That they do not cite this fear could suggest that the belief that the regulator will punish misdeeds is so widespread as to be taken for granted: interview respondents did not even think to remark on this belief as its influence on their motivations to apply is obvious. Alternatively, firms may have motives unrelated to fear of punishment.

b. Moral reputation

The questionnaire results show that most respondents believe that the FCA aims to help innovative companies (M = 3.53, Median = 4, SD = 0.16). More than half of the interview respondents state that the FCA is generally supportive of innovative companies. “Supportive” for respondents did not mean that the FCA is biased or unlikely to criticise or sanction illegal/unethical innovations. Rather, interview respondents praise the FCA for “trying to work with more fintech and future tech companies”,Footnote 104 being “open”Footnote 105 and willing to “engage” – to listen to ideas and try them out.Footnote 106

This reputation made firms more motivated to apply out of expedience. Sandbox participation requires firms to trust the regulatory agency. In a sandbox, participants share a lot of information about the inner workings of their products and businesses. The regulator has the power to summarily quash an innovative product.Footnote 107 A belief that the regulator was open and progressive made firms expect that the sandbox would ultimately be good (or at least not bad) for their business. They trusted that, in the sandbox, the regulator would not betray the firm’s candour by blithely shutting down innovations. As one respondent said, because of “how forward thinking the FCA was and hopefully still is” his firm “wouldn’t really have a hesitation” in applying for the sandbox.Footnote 108 These kinds of comments are supported by more implicit interview analysis. Respondents who saw the regulator as facilitative of fintech were also more motivated.

Those few respondents who did not see the regulator as a facilitator were also those who were less motivated to apply. A cynical minority of interview respondents believe that the FCA’s stated lofty goals are insincere: the sandbox is a cosmetic commitment to innovation from a regulator who actually intends to maintain the status quo. This belief undermines their motivation to apply for reasons of expedience. They do not believe that the FCA will deliver on the supposed benefits of the sandbox. One respondent, for instance, was unmotivated because – through industry gossip – he formed the impression that the FCA was not really trying to help businesses like his: “people had gone into the sandbox and hadn’t got the answers that they needed [so] I just don’t think it’s valuable”.Footnote 109 The belief that the regulator is lying about the real goals of the sandbox, furthermore, meant that these firms were less motivated to apply in order to ensure compliance because they had become mistrustful and resentful. One respondent said he had become “a lot more cynical” about the FCA’s intentions regarding fintech, undermining his motivation to apply to the sandbox and even to comply with FCA rules in general.Footnote 110

c. Procedural reputation

The questionnaire results show that the FCA has a reputation for procedural correctness among firms in the sample (M = 3.88, Median = 4, SD = 0.24). The majority of interview respondents agree, describing the FCA as: “objective … highly credible”,Footnote 111 “transparent”,Footnote 112 “appropriate”Footnote 113 and not “promoting specific” technologies or businesses.Footnote 114 Questionnaire results suggest that the FCA is typically seen by fintech firms as fairly inflexible on procedure (M = 3.85, Median = 4, SD = 0.66). The interview results show that similar beliefs: (1) are held by firms who have never participated in the sandbox before; and (2) were held by firms who have participated in the sandbox prior to their first time participating. In other words, when firms have not participated in a sandbox, they usually see the regulator as procedurally inflexible.

The FCA’s reputation for procedural correctness motivates firms to apply in order to boost their corporate reputation. The belief that the FCA is procedurally correct is widely held by respondents who are motivated to apply. Several respondents said they wanted to apply because the FCA is seen as procedurally credible and reliable by their business partners and investors. “The FCA carries a lot of credibility”, one respondent explained, “so, if [partners/investors] look at us, they see the FCA sign and they go: ‘okay there must be something to it’”.Footnote 115 Another respondent similarly concluded: “You cannot get a better reference [than the FCA’s] in the market”.Footnote 116 The sandbox “stamp of approval” was a particularly powerful incentive for firms marketing products that do not require them to have an authorisation (firms who sell to corporate clients and not the general public or whose products do not otherwise trigger regulatory requirements). Such firms wanted to prove the legality of their products but had no regulatory process to go through. As one respondent stated:

The goal was more reputational. Because when you are a small company, when you say something it has a certain weight, which is very small. But if the same thing is said by somebody else it has a very different weight. It is a credibility issue. As a small and reasonably unproven start-up you have a credibility issue in the regulated space, right? In something that is as conservative and complex [as] the world of banking and financial services.Footnote 117

A couple of firms said business partners and potential investors pressured them to apply. Here, partners and investors appear motivated by the FCA’s good procedural reputation. For some, the goal was for the firm to gain assumed credibility by association with a respected regulator. Others wanted any regulatory kinks to be ironed out before they invested in the innovative product. The sandbox was a way to have the FCA – a regulator whose procedural excellence they trusted – do due diligence.

I think the challenge we had is that [business partners] tend to be quite risk averse. So actually to getting a product live in the market, the fact that we were in the sandbox gave our very conservative [business partner] the comfort that they needed to ensure that everything from their side, they were also going to be protected.Footnote 118

Respondents were quick to tell me that everyone understands that sandbox participation does not actually mean that the FCA endorses them or the product. Yet respondents imply that participation operates as a pseudo-credentialisation by a respected regulator, and this is an important motivation.

Some respondents, furthermore, imply that the FCA’s procedural correctness made them more motivated to apply in order to ensure compliance with the law. Many firms remarked that the point of the sandbox was to see whether their products could function within existing regulatory frameworks. They wanted the FCA to be flexible only insofar as the agency would be open to considering whether innovative products might potentially comply.

One might expect that a reputation for procedural correctness would make firms less motivated to apply to the sandbox for reasons of expedience. Regulatory sandboxes are, after all, marketed as offering a flexible approach to facilitate experimentation. Interview analysis, however, showed no associations between a belief that the regulator was procedurally flexible and a firm’s motivation to apply. Explicitly, a few respondents (4/21) said that they were dissuaded out of concerns about administrative costs. Respondents tend to imply, however, that this was due to procedural strictures of sandboxes in general (eg “sandboxes always come with strings attached”Footnote 119 ).

We see some different responses among firms who were going through or had completed the sandbox. These firms tend to report that, in the past, they saw the FCA as procedurally strict, but they now perceive them as flexible. Yet this change did not seem to be associated with a reduced motivation to apply for future cohorts. If anything, these firms tended to see more flexibility as positive. This implies that motivations for applying to a sandbox, and their relationship with regulator reputation, may change once a firm has already graduated from its first cohort.

d. Technical reputation

The questionnaire results show that most respondents believe that the FCA has the technical expertise required to fulfil its role (M = 3.84, Median = 4, SD = 0.21). In interviews, it was somewhat difficult to separate technical reputation from performative and procedural reputation. There is a degree of conceptual overlap between these reputations,Footnote 120 particularly as they pertain to sandbox participation. The respondents who most explicitly discuss the FCA’s technical reputation tend to discuss the ways in which the agency lacks expertise in regard to their technological sector (6/21).

There is some evidence that a lacking technical reputation made some firms less motivated to apply because they thought either that the sandbox would not be expedient and/or that it would not help them ensure their compliance. Several firms said that they did not think that the regulator could answer their questions, so the sandbox was not worth it. One respondent, for example, remarked that his firm was so far ahead of the regulator in technical knowledge that there was no way the FCA could assist them:

To go into the sandbox seemed like a step backward … And what would we achieve except dialogue with the regulators? … We actually have a lot of people knocking on our door saying “how did you do this, why did you do it, what’s the process?”Footnote 121

Other firms, however, were willing to apply despite questioning the FCA’s expertise. These latter respondents gave the impression either that they had faith that they could teach the FCA what it needed to know in order to assist them and/or that they had other motivations, such as boosting corporate reputation, unrelated to the regulator’s technological expertise.

V. Discussion

This article aimed to explore why stakeholders, specifically firms, are (un)motivated to participate in regulatory processes designed to identify and manage the risks of emerging technologies and what role regulator reputation might play in motivating participation. A case study of the UK’s regulatory sandbox for fintech finds that firms have a range of practical, normative and reputational motivations. The FCA’s reputation for procedural correctness, moral commitment to innovation and high performance made firms more motivated to apply. Distinct beliefs about the regulator had distinct relationships with different kinds of motivation. Centrally, the case study provides further empirical evidence supporting Carpenter’s observation that, when regulators have a strong procedural reputation, firms become more motivated to engage constructively with them in order to enhance their own corporate reputation – to gain credibility by association.Footnote 122

This article further aimed to position sandboxes within existing bureaucratic reputation scholarship on participation in regulatory assessments, design and implementation in a European context. The results further support the notion that regulator reputation is an important factor explaining why some participation exercises succeed and others fail.Footnote 123 Previous literature has focused on how regulator reputation influences agencies to invite certain kinds of participation.Footnote 124 With this study, I begin to expand the discussion to include a more nuanced account of why stakeholders might take up – or ignore – those invitations. The results imply that, when seeking to attract good-quality, good-faith participation from a stakeholder audience, a regulator’s reputation will sometimes be an asset and, sometimes, a liability.Footnote 125

Practically, the case study results suggest that simply transferring sandbox designs that were successful in certain national jurisdiction may not necessarily lead to similar success at the European level. EU regulators may not have the same reputation with their stakeholders as the FCA does, and they may need to consider how they might manage that image as part of sandbox implementation.Footnote 126 In regard to sandboxes targeting fintech specifically, regulator reputation may be particularly significant for attracting firms from outside the EU. Finance is a highly mobile global industry. Fintech firms can relatively easily choose where they will be based, and regulation is a key consideration.Footnote 127 Fintech firms find sandboxes appealing.Footnote 128 That said, today there are myriad international options from which to choose. The EU thus faces regulatory competition in attracting firms to their sandbox and, by extension, to Europe. The study findings imply that having a financial regulator (or regulators) with a good reputation with international fintech could be a competitive advantage. The UK experience, furthermore, offers lessons about how to effectively market sandboxes to firms in high-technology sectors. Key is that respondents were very motivated to apply, even when they had no practical reasons to do so, because participation was seen as good for their corporate brand. The UK’s sandbox is high-profile, selective and repeats through regular cohort cycles. Firms see others make the cut and get valorised in the press, and this drives participation in ways that a more low-profile, non-selective or one-off process almost certainly would not.

Normatively, this study has implications for debates about the extent to which increased stakeholder regulatory participation, particularly by firms, facilitates capture.Footnote 129 Where stakeholders participate in order to bias regulatory assessments or decision-making, this can undermine the quality and legitimacy of the process.Footnote 130 Respondents in this case study, however, very rarely said that they were motivated to participate for reasons associated with capture (influencing policy or improving their relationship with the regulator). This could be interpreted as a social desirability effect. Covert lobbying is stigmatised, and firms may not want to admit to it. From a reputational perspective, however, firms may be sincerely motivated to participate in regulatory assessment, design and implementation in order to boost their corporate credibility rather than capture the process. This would help to explain why firms were more motivated to work with a regulator that they saw as procedurally correct. From a reputational perspective, agencies and stakeholders are mutually dependent on one another for credibility and therefore have a vested interest in the other behaving in credible, legitimate and unbiased ways.Footnote 131 This study thus reinforces the notion that stakeholders have complex – political as well as economic – motivations for regulatory participation.

1. Limitations and future research

Moderate differences between the interview and questionnaire imply that the results may be sensitive to method choice. Furthermore, the sample size for this case study was small, which is likely explained by the population (disproportionately small, young, private companies) and research focus (on the sensitive topic of beliefs about the regulator). Some kinds of firms – notably big, well-established companies – are underrepresented. Others – notably ex-sandbox participants – are somewhat overrepresented. Furthermore, regulated firms represent a particular kind of stakeholder group. Reputational theory suggests that different kinds of reputation will appeal to different kinds of stakeholder (eg researchers, civil society groups).Footnote 132 Finally, the UK’s sandbox for fintech represents a specific context, and one cannot necessarily generalise its results to represent all regulatory participation. To further build upon and validate the theory, future research would be required to examine the motivations of various kinds of stakeholder groups in a range of regulatory participation contexts. This study offers several findings that could be developed into hypotheses for, for instance, larger-scale survey studies.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/err.2021.44