I. Setting the scene – composite procedures and judicial review: lost in co-operation?

In the EU, no medicinal product may be placed on the market without a marketing authorisation.Footnote 1 Such a marketing authorisation may be obtained via four procedures, representing three different degrees of integrated administration: the national procedure; the Mutual Recognition Procedure; the Decentralised Procedure; and the Centralised Procedure. While purely national marketing authorisations in the individual Member States are still in existence, their applicability is limited. If a product is to be marketed in more than one Member State, the Mutual Recognition or the Decentralised Procedure have to be used. Finally, the Centralised Procedure provides for a decision-making process at the EU level, leading to a marketing authorisation valid throughout the Union granted by the European Commission.

While traditionally in EU administration, adhering to the framework of executive federalism,Footnote 2 preference was given to indirect administration of EU law through the Member States, complemented by direct administration through EU bodies in accordance with the subsidiarity principle, the EU administrative law scholarship is increasingly uncovering and discussing an array of procedures which do not conform to this strict national and EU level dichotomy.Footnote 3 This phenomenon has been termed “composite administration”Footnote 4 and the ensuing procedures have been defined as “(…) procedures entailing the input of administrative actors from different jurisdictions, and in which the final decision, issued by a Member State or a EU authority, is based on procedures involving the more or less formalized input of the various participating authorities”.Footnote 5 These procedures are furthermore characterised by a “decisional interdependence between national and EU authorities”Footnote 6 in the sense that no step of the process can be taken unless all prior steps have been taken.

However, composite procedures challenge basic core principles of European administrative law, such as accountability,Footnote 7 participationFootnote 8 and judicial review.Footnote 9 It is the latter on which we will focus in this article. Article 47 of the Charter promises the right to effective judicial protection, which is also recognised as general principle of EU law.Footnote 10 In practice, however, while composite procedures nowadays are a common procedural path in the EU’s composite (or integrated)Footnote 11 administration, judicial protection has not followed suit and this right can fall between the cracks of administrative procedures, which increasingly do not conform to the direct/indirect administration division and its clear-cut jurisdiction division.Footnote 12

These concerns regarding reviewability are not merely theoretical, but have already surfaced in the Decentralised Procedure for pharmaceutical marketing authorisations in the Astellas Pharma case, where the determination of reviewability and jurisdiction over an aspect of a marketing authorisation granted within the Decentralised Procedure raised complex questions.Footnote 13 Although the marketing authorisation procedures in the pharmaceutical area have been studied,Footnote 14 the impact of their composite nature on judicial reviewability has not been extensively analysed.Footnote 15

This article examines the challenges composite procedures pose to judicial review in the marketing authorisation procedures for pharmaceuticals. These procedures provide an interesting case study, as the procedures can be characterised as multi-level, cross-level and multi-institutional, depending on factors that the marketing authorisation applicant can only partially influence through his choice of procedure. In the area of pharmaceuticals, a curious procedural mix of national, mutual recognition and centralised European procedures co-exist.Footnote 16 Moreover, procedures that might look like direct or indirect administration from the outside, upon closer examination reveal elements of vertical and horizontal administrative cooperation. Member States contribute their expertise and are part of the decision-making process even at the EU level stages, and in some procedures disagreement between the Member States can trigger an element of EU level arbitration. While this article is devoted to an analysis of the marketing authorisation procedures, it should also be noted that the enforcement of the pharmaceuticals regulatory framework through the Penalties Regulation is characterised by collaboration and exchange of information between the Commission, the European Medicines Agency, and national authorities, which leads to comparable challenges with regard to judicial review of the different procedural steps as the ones we raise in this article.Footnote 17

This article proceeds as follows: firstly, the authorisation models will be examined, with special attention to the steps of the decision-making and their legal nature and consequences. Secondly, the reviewability of these steps will be analysed, and the gaps in judicial accountability will be highlighted. The article will conclude with some recommendations as to how the potential accountability gaps could be filled.

II. Mapping the marketing authorisation procedures for pharmaceuticals in the EU: four shades of integration

As was pointed out earlier, pharmaceuticals can be authorised in a national, Mutual Recognition, Decentralised or Centralised Procedure. Which procedure is applicable depends on the where the product is meant to be marketed and also the category of pharmaceutical product in question. Apart from the purely national authorisation procedures, the other three procedures are composite at least to a certain degree, as the granting of a marketing authorisation leads to the close collaboration of EU and national actors in various steps of these procedures.

1. The national procedure

The national procedure is only applicable in cases where the product is to be marketed in only one Member State and does not fall into the categories of pharmaceuticals for which the Centralised Procedure is obligatory.Footnote 18 In these procedures, an application for a marketing authorisation has to be submitted to the national competent authority of the Member State in question. The whole procedure is carried out within the administrative remit of that Member State and no input from other Member States or the EU is received. The national procedure is thus a very classic case of indirect administration and does not qualify as composite procedure. The national procedure may not be used where the product has already obtained a marketing authorisation in another Member State, as this would fall under the Mutual Recognition Procedure. Applications in several Member States simultaneously are also prohibited, as these cases fall under the Decentralised Procedure.

2. The Mutual Recognition and Decentralised Procedures

In principle, both the Mutual Recognition and the Decentralised Procedure are national procedures as well.Footnote 19 The final decision on the marketing authorisation is adopted by each Member State in which an authorisation was requested. However, these procedures were introduced in order to prevent diverging decisions for the same product in various Member States. Due to the sensitive nature of pharmaceutical products for public health, the application of mutual recognition based on legal harmonisation without any proceduralised coordination between the Member States had proven futile.Footnote 20 Therefore, in this case, the mutual recognition principle, as established in the Cassis de Dijon case,Footnote 21 was embedded in a composite procedural framework.

The Mutual Recognition Procedure is the compulsory procedure for applying for a marketing authorisation in a Member State, when an authorisation has already been granted in another Member State.Footnote 22 The Decentralised Procedure is triggered if no marketing authorisation has been granted by any Member State and the application is made simultaneously in several Member States.Footnote 23 The procedures follow the same pattern, only the starting point is different, as under the Mutual Recognition Procedure one Member State has already granted a marketing authorisation, whereas in the Decentralised Procedure no marketing authorisation has been granted by a Member State.

As will be explained in detail below, three procedural phases can be distinguished: (i) a national phase with reference and concerned Member States; in case of disagreement between the Member States (ii) an intra-administrative phase in the Coordination Group for Mutual Recognition and Decentralised Procedures (CMDh);Footnote 24 and, in case of disagreement in the CMDh (iii) a binding supra-national arbitration by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the Commission.Footnote 25 Thus, depending on the level of agreement or disagreement between the Member States about a specific marketing authorisation, the information gathering and decision-making steps and actors involved in the procedure vary.

a. The national phase

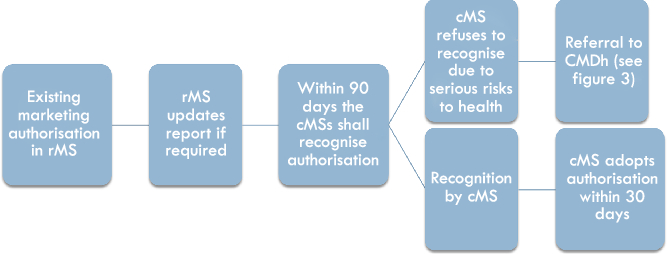

If a marketing authorisation has already been obtained in one Member State (the so-called reference Member State, rMS), the marketing authorisation holder may ask for the recognition of this marketing authorisation in other Member States (the so-called concerned Member States, cMS), by applying for the Mutual Recognition Procedure (see Figure 1). The rMS will then update its assessment report and other required documentation and send it to the cMS within 90 days.Footnote 26 After validation,Footnote 27 the cMSs have 90 days to approve the assessment report and further documents provided. The mutual recognition principle that forms the basis of this procedure means that the cMSs must approve the report received from the rMS.Footnote 28 Each cMS then has to grant the marketing authorisation within 30 days.Footnote 29 A cMS can only refuse approval based on potential serious risks to human health, which leads to a referral of the procedure to the CMDh.Footnote 30

Figure 1: The national phase in the Mutual Recognition Procedure

Thus, where no potential serious risks to human health are identified, the Mutual Recognition Procedure is composite in the sense that all cMSs have to take administrative decisions based on the information and decision provided by another Member State, but there is no structural “cooperation mechanism” foreseen between the rMS and the cMSs on the authorisation question. However, if one or more of the cMSs do have concerns regarding potential serious risks to human health, these are communicated and discussed between the Member States during a 90-day period the cMS(s) have to approve the assessment report of the rMS.Footnote 31 In this case, either the issue is resolved within the 90-day deadline and the final decisions granting a marketing authorisation are adopted separately in all cMSs, or the procedure is referred to the CMDh.

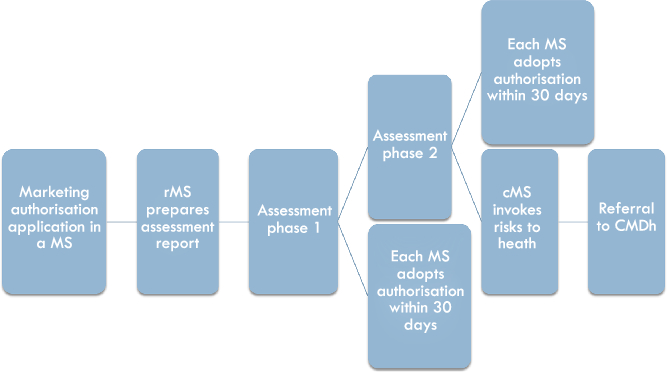

The Decentralised Procedure facilitates the parallel application in several Member States, in cases where no marketing authorisation has been granted in any Member State (see Figure 2). The application will be submitted to all Member States for which the applicant desires authorisation, but the assessment is carried out by one reference Member State chosen by the applicant. Once all Member States have validated the dossier, the rMS has 120 days to draft an assessment report (assessment phase 1).Footnote 32 During this time, the rMS will discuss the assessment with the cMSs, which means that if consensus is reached, the procedure can be closed and authorisations will be granted by the Member States. If consensus is not reached within the 120-day period, an additional period of up to 90 days may be granted for reaching consensus (assessment phase 2).Footnote 33 If consensus is reached in assessment phase 2, the Member States will grant marketing authorisations within 30 days.Footnote 34 However, if consensus cannot be reached, because a cMS considers that there is a potential serious risk to human health, a referral of the procedure to the CMDh is made.Footnote 35

Figure 2: The national phase in the Decentralised Procedure

The Decentralised Procedure, although the rMS is in the driving seat and carries out the assessment of the application, theoretically allows for an exchange of information and discussion of potential differences between the rMS and the cMSs.Footnote 36 This stands in contrast to the Mutual Recognition Procedure, where the decision in the rMS has already been made at the start of the procedure and leaves less room for collaboration between the rMS and cMSs. The Decentralised Procedure is thus, as AG Bobek put it, a system based on “co-decision” logic.Footnote 37

b. The intra-administrative phase

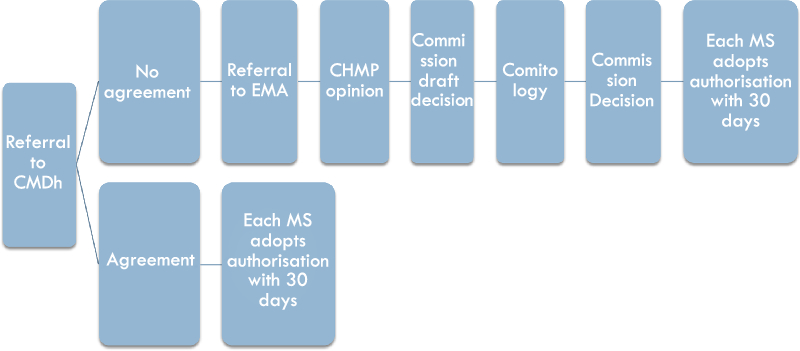

In both the Mutual Recognition Procedure and the Decentralised Procedure, if the rMS and cMSs can agree on the marketing authorisation application, the composite element of the procedure can only be seen in the horizontal exchanges between the competent authorities of the Member States where marketing authorisation is requested. However, where the rMS and cMSs cannot agree on whether to grant a marketing authorisation, the procedure is referred to the CMDh (see Figure 3). This referral is automatically initiated when at least one Member State does not approve the assessment report provided by the rMS within the 90 days deadline forseen in Article 28(4) of Directive 2001/83.Footnote 38

Figure 3: The intra-administrative phase and the binding supra-national arbitration phase

The CMDh is composed of one representative per Member State, as well as the Commission and the EMA as observers.Footnote 39 It is intended to provide a forum for deliberation to facilitate mutual recognition, and it will try to reach a consensual agreement for disputes between the rMS and cMSs on potential serious risks to human health within 60 days.Footnote 40 It is not part of the European Medicines Agency; however, the Secretariat to the CMDh is provided by the EMA and the monthly meetings take place at the EMA premises.

The CMDh referral does not end with a formal opinion or decision of the CMDh, but Article 28(3) of Directive 2001/83/EC states that: “If (…) the Member States reach an agreement, the reference Member State shall record the agreement, close the procedure and inform the applicant accordingly”. If consensus on the authorisation is reached, the competent authorities in the cMSs will grant national marketing authorisations within 30 days.Footnote 41 If no consensus is reached within the allocated time, the procedure is referred to the EMA for arbitration,Footnote 42 which marks the beginning of the supra-national arbitration phase.

c. The binding supra-national arbitration phase

If the Member States cannot reach consensus within the CMDh, the arbitration takes place at the EU level (see Figure 3). Within the EMA, the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) will from an opinion on the marketing authorisation application.Footnote 43 The CHMP is the agency’s main scientific committee for human medicinal products and is composed of one chair, elected by the serving CHMP members, as well as one member plus alternate for each Member State, and one representative (plus alternate) for Iceland and Norway.Footnote 44 Thus, although the EMA is an EU body, the Committee that carries out the assessment is composed of experts appointed by the Member States, usually belonging to the national competent authorities.Footnote 45 The CHMP will adopt its opinion within 60 days.Footnote 46 In case of a negative opinion, the applicant will be informed before the adoption of the opinion and has the chance to request a re-examination.Footnote 47 The final EMA opinion is sent to the Commission, which prepares a draft decision. The Commission’s draft decision is subject to comitology within the examination procedure laid down in Article 5 of Regulation (EU) 182/2011,Footnote 48 in which the Standing Committee on Medicinal Products for Human Use, consisting of Member State representatives, votes on the adoption of this draft decision by qualified majority.Footnote 49

After the comitology procedure, the Commission adopts the final decision.Footnote 50 This Commission Implementing Decision is addressed to all Member States and those Member States involved in the Mutual Recognition or Decentralised Procedure are required to follow it.Footnote 51 Thus, after the Commission decision, the national authorities have 30 days to comply with the Commission decision, and either adopt or refuse a marketing authorisation through a decision addressed to the applicant.Footnote 52

3. The Centralised Procedure

The Centralised Procedure leads to a marketing authorisation that permits the marketing of a medicinal product in the whole EU (see Figure 4).Footnote 53 The procedure is compulsory for certain innovative products,Footnote 54 and can be optionally chosen for other products.Footnote 55

Figure 4: The Centralised Procedure

In the Centralised Procedure, the application is submitted to the EMA.Footnote 56 Within the EMA, the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) carries out the benefit/risk analysis and provides a scientific opinion on the marketing authorisation of the product in question. The CHMP appoints one of its members to act as rapporteur, taking the lead in preparing the scientific assessment of the application and the drawing up of a report.Footnote 57 Moreover, a co-rapporteur is nominated who either will prepare a critical assessment of the report drawn up by the rapporteur, or will write their own assessment report, depending on the choice of the Committee.Footnote 58 After the assessment the CHMP adopts a favourable or unfavourable opinion.Footnote 59 The decision-making usually takes place by consensus, but requires at least absolute majority of the Committee members.Footnote 60 In case of an unfavourable opinion, the applicant may request a re-examination.Footnote 61

The final EMA opinion is sent to the Commission, which adopts a draft decision within 15 days,Footnote 62 subject to comitology. Although the EMA opinion is only of advisory nature, it is notable that the Commission usually follows the CHMP opinion.Footnote 63 A positive decision adopted by the Commission, in the form of a Commission Implementing Decision, grants a marketing authorisation decision addressed to the applicant, being valid within the whole Union for five years, meaning that the decision is binding upon the Member States.Footnote 64

At first sight, this procedure does not seem composite at all, but very much an example of direct administration. The whole process, including the final decision, is carried out at the EU level through the European Medicines Agency and the European Commission. However, upon close examination it becomes clear that the CHMP is composed of members nominated by the Member States, the overwhelming majority of whom are representatives of national competent authorities. The rapporteur and co-rapporteur carrying out the scientific assessment which forms the basis of the EMA opinion rely on the administrative structures of their national competent authorities for their scientific expert assessment. Thus, although the CHMP opinion is a measure of the EMA, its coming into being heavily depends on expertise and information provided by national competent authorities. Moreover, also in the comitology stage, representatives of the Member States take part in the process. Thus, the centralised procedure is also a composite procedure.Footnote 65

III. Gaps of judicial protection in the composite procedures used for marketing authorisation of pharmaceuticals

The section above has shown that the procedures to be followed in the marketing authorisation of pharmaceuticals are prime examples of composite procedures, involving a variety of actors, actions and levels of governance. While administrative decision-making procedures are increasingly integrated, however, judicial review still remains firmly anchored to a dualistic vision, whereby the judicial level competent in shared administrative procedures corresponds to the administrative level that has adopted the act under challenge. The gaps this causes in the judicial review of the three composite procedures discussed will be examined below. The article will not be concerned with all possible aspects of judicial review in the authorisation of pharmaceuticals, but will only examine the question of access to the court and reviewability of all steps of the decision-making process where gaps in judicial protection have been identified by the authors.

We will not only examine the access to court for marketing authorisation applicants, but where appropriate will also take into account acccess to court for competitors or civil society organisations who might want to oppose an authorisation. Consumer associations might want to go to court when they disagree about the safety of the marketed product. Admittedly, in the Olivieri case, the Court has established, in the context of a Centralised Procedure, that the marketing authorisation procedure is entirely bilateral between the applicant and the assessing authorities.Footnote 66 Nevertheless, and despite the lack of any general right of participation or intervention of public interest organisations in a marketing authorisation procedure, the idea of a “Community based on the rule of law”Footnote 67 and the right to effective judicial protectionFootnote 68 require that actions of EU public authorities can be subject to judicial scrutiny, not only by the addressees, but also by interested third parties or associations promoting general and collective interests.

For competitors, it might be argued, first of all, that competitors could also exercise a “public interest” role as watchdogs where they litigate against a presumably unsafe product;Footnote 69 secondly, and specifically in case of marketing authorisations of pharmaceuticals, the legislative framework allows to refer to and build upon the marketing authorisation of another product, eg to authorise a generic product. For competitors it might therefore be important to be able to challenge a marketing authorisation because they might rely on marketing authorisation dossier of an already authorised product to authorise their (generic) product.Footnote 70 Moreover, the marketing authorisation decision determines how long a pharmaceutical is protected from competition of generic producers, which can be the object of dispute between originator and generic producers as exemplified in the recent Astellas Pharma case.Footnote 71

1. The Mutual Recognition and Decentralised Procedures

a. Scenario 1: consensus between Member States and marketing authorisation is granted

If, in the Mutual Recognition Procedure or in the Decentralised Procedure, no disagreement between Member States arises, the marketing authorisation is granted in the form of a national administrative decision. In these cases, a competitor or a civil society organisation might want to challenge the authorisation, arguing that the scientific basis for the authorisation was flawed.

In accordance with the strict separation of jurisdictions, a challenge against the marketing authorisation can only be brought before the national court of the state which has adopted the respective decision, thus the rMS or a cMS. However, if it is argued that, for example, the report submitted by the rMS is flawed, the court of the cMS will not be able to assess the report submitted by the rMS, because it is a measure stemming from a different legal system. As AG Bobek put in a recent opinion, “the territorial nature of each of the marketing authorisations and the necessary correlating territorial nature of judicial review” will create obstacles to the control of acts or actions originating in another jurisdiction.Footnote 72 As there is no “horizontal preliminary reference”, the only alternative for the applicant is to challenge the report of the rMS before the competent national court of the rMS. In principle this possibility is open to applicants, depending on national rules of standing, but the report will hardly be considered a reviewable act, as it is only an intermediate step in the decision-making process. This problem has again been highlighted by AG Bobek: when discussing the Decentralised Procedure, he considered the nature of the report in question and concluded that “[I]n a number of Member States, it is quite likely that that report may be classified as a preparatory act and thus not amenable to judicial review”.Footnote 73

The Borelli ruling, in which the CJEU held that a rule of national law that prevented legal action from being taken against a mere preparatory act would be in violation of the right of access to justice,Footnote 74 does not seem to open any possibility for judicial review in the case at stake. This is because the duty of national courts to review a national preparatory measure has been grounded by the court in the fact that this measure “is binding on the Community decision-taking authority and therefore determines the terms of the Community decision to be adopted”,Footnote 75 hence a situation in which there is no discretion for the authority issuing the final decision.Footnote 76

In conclusion, in court of a cMS it is possible to challenge the authorisation of that cMS but not the report or authorisation of the rMS, as the “act” originates in different legal system; in an rMS, it is in principle not possible to challenge the report due to its preparatory nature, unless, in (an unlikely) application of the Borelli ruling, the court was ready to disregard national procedural rules barring such a claim.

It should be stressed that, while this gap of judicial accountability arises equally in Mutual Recognition and in Decentralised Procedures, it is in the latter type of procedures that the gap is more worrisome. This is because, while in the Mutual Recognition Procedure there is a prior authorisation, and the cooperation between Member States is limited to the sharing of the updated assessment report from the rMS to the cMS, in the Decentralised Procedure, the sharing of risk-related information forms much more of a “web” of relations between Member States. As AG Bobek recently put it, “[I]n a Decentralised Procedure, all of the Member States participate in the elaboration of their decision at the same time. To put it metaphorically, cooking with friends is not the same as sharing meals that have already been prepared”.Footnote 77 In such a situation, apart from the gap highlighted above, it may also be much more complex for a potential applicant to even be able to re-trace the source of a certain piece of information which led to the rejection of the marketing authorisation.

b. Scenario 2: no consensus between Member States (a cMS considers that there are serious risks to health), referral to the CMDh, which reaches an agreement (leading either to the denial or the granting of a marketing authorisation)

The question which arises in such a situation is, first of all, whether a potential applicant could challenge a referral to the CMDh; secondly, whether the actions themselves of the CMDh could be attacked; and, thirdly, whether the final measure of denial or granting of the marketing authorisation could be challenged.

Starting from the last step, while an applicant could challenge before a national court the denial or granting of the marketing authorisation, it is doubtful whether the national court would be able to effectively review this measure if the applicant claims that the measure is based on a flawed course of action at the level of the CMDh (eg some procedural error was made in the CMDh procedure or the CMDh disregarded some rules of the applicable legislative framework). This is because the CMDh is not a national administrative authority whose acts can be reviewed by the national courts.

The actions of the CMDh are therefore difficult to review before a national court. So can an applicant then challenge the actions of the CMDh before the European courts pursuant to Article 263 TFEU? A hurdle seems to be the so-called “authorship criterion”, as only acts of the EU institutions, and “acts of bodies, offices or agencies of the Union” may be challenged under Article 263. The CMDh is a body composed of national representatives which therefore does not seem to meet these criteria. Hence, it does not seem possible to directly challenge the actions of the CMDh in an annulment action either.

However, in light of recent jurisprudential developments, it could at least be argued that the CJEU might have jurisdiction to indirectly review the actions of the CMDh in preliminary questions of validity under Article 267 TFEU. In James Elliott, the CJEU held that it had jurisdiction in preliminary questions over the acts of the bodies which are created “in implementation of EU law”.Footnote 78 As the CMDh is a body created in implementation of secondary EU law, there is potential to argue that preliminary questions of validity over its actions will be available.

A different question, apart from the nature of the body in question, is linked to the nature of the actions of the CMDh. Indeed, as mentioned above, the referral procedure does not end with a formal opinion or decision of the CMDh, but Article 28(3) of Directive 2001/83/EC merely states that: “If (…) the Member States reach an agreement, the reference Member State shall record the agreement, close the procedure and inform the applicant accordingly”. It can be asked if, in light of this provision, there is an actual measure or action to be challenged in the first place. It may be a case of les than careful drafting, but Article 28(3) seems to suggest that the CMDh is not actually capable of carrying out actions, which remain imputable to the Member States acting within a collective body.

The last question linked to the CMDh is whether an applicant could challenge a referral to the CMDh, which “moves” the Mutual Recognition and Decentralised Procedures from the national level to the intra-administrative level. Indeed, a market operator might have an interest in keeping the authorisation procedure at the national level because of the delays (and related loss of profit) involved, but also because, as shown above, the actions of the CMDh can hardly be controlled and the operator does not know how the CMDh will decide. In this situation, the operator is faced with a gap of judicial protection because it cannot oppose the referral to the CMDh. This is because the referral is a procedural step, which is automatically triggered, where a cMS does not agree with the positive assessment report of the rMS. The actual effect on the applicant’s legal sphere will only be produced at the end of the process when the decision on the marketing authorisation is issued.

This conclusion is supported by a recent order of the General Court concerning another type of referral in the same field of pharmaceuticals.Footnote 79 In this case the referral was a so-called “Union interest referral” pursuant Article 31 of Directive 2001/83, which refers a question to the relevant EMA Committee, the CHMP.Footnote 80 In this type of referral the procedure is initiated either by a Member State, the Commission or a marketing authorisation holder, due to concerns relating to the quality, safety or efficacy of a medicine. The company alleged that the conditions for launching the review procedure were not fulfilled. The General Court dismissed the action as inadmissible, considering that, according to constant case law,Footnote 81 the initiation of a procedure does not affect the legal position of the company. Moreover, according to the court, within a procedure consisting of several steps, when the final decision is challenged before the courts, the interim steps can also be attacked. This statement is line with the CJEU’s general approach to “derivative illegality”Footnote 82 at EU level, on the basis of which “any unlawful features vitiating … a preparatory act must be relied on in an action directed against the definitive act for which it represents a preparatory step”.Footnote 83 Such derivative illegalilty is exemplified by a recent ruling in an appeals case brought by the Dr August Wolff GmbH against a Commission Implementing Decision that was taken in an Article 31 referral procedure.Footnote 84 The Court annulled the Implementing Decision, based on its finding that the rapporteur appointed in the EMA CHMP for the referral was not sufficently impartial.

The General Court, taking a rather legalistic approach, considered therefore that only measures creating “binding legal effects” capable of modifying the legal sphere of the applicant, may be subject to an annulment action. Furthermore, the Court suggested that, for all other prejudicial effects created by these intermediate acts, the action for Union liability could be launched once the illegality of the final decision of the process was found.

If the Court denied the reviewablility of a referral procedure that has to be specifically triggered, it can be inferred that it is even less likely to admit the reviewability of a referral in the Mutual Recognition and Decentralised Procedure, which consitutes a “normal” procedural step in case of disagreement between the Member States and is not triggered by a dedicated act of a Member State. In conclusion, when the intra-administrative phase of the Mutual Recognition and the Decentralised Procedures is activated, an applicant cannot object to the referral and can only indirectly (if ever) challenge the actions of the CDMh which are the basis of the final decision on the marketing authorisation.

c. Scenario 3: no consensus between Member States (a cMS considers that there are serious risks to health), referral to the CMDh, which does not reach an agreement (leading to a referral to EMA and a final Commission decision)

Subsection b above has examined the gaps of judicial protection in respect of situations in which the CMDh is able to reach consensus and a final national measure concludes the process. However, it is also possible that no consensus is reached by the CMDh on whether an authorisation can be granted, and the matter reaches the supra-national arbitration phase. The absence of consensus and with that the referral itself to the EMA are not open to challenge, for the same reasons already discussed in the referral step of Scenario 2, even though it entails a loss of time and possible financial loss for the applicant.

Neither can the opinion of the EMA adopted during the referral be the subject matter of a direct action, again because of its preparatory nature and consequent incapability of directly affecting an applicant’s legal sphere. However, the opinion will be reviewed by the European courts in a direct action against the final Commission decision. This is confirmed by the Olivieri case, in which the Court of Justice stated that the content of an EMA’s opinion, and also that of the assessment reports upon which it is based, are an integral part of the statement of reasons for the final decision.Footnote 85

The final step of the process is a Commission Implementing Decision addressed to the Member States, which certainly constitutes a reviewable act for the purposes of an action for annulment. However, competitors and consumer associations (in case the decision is positive) will be faced with considerable difficulties proving that they have standing in such a direct action. This is because the Commission Implementing Decision may not be qualified as a regulatory measure, because, although it is not taken with a legislative procedure, it is not of general application. The latter concept, according to settled case law of the Court of Justice, refers to situations in which an act “applies to objectively determined situations and produces legal effects with respect to categories of persons envisaged in a general and abstract manner”.Footnote 86 In the case at stake, the Commission Implementing Decision applies to specific marketing authorisations (hence objectively determined situations), but only produces legal effects on the Member States and, through the final national authorisation, the marketing authorisation applicant. On this basis, the measure cannot profit from the more relaxed standing requirements for regulatory measures introduced by the Lisbon Treaty in Article 263(4) TFEU. Moreover, the Commission Implementing Decision also entails implementing measures (in the form of a final national measure granting or denying the marketing authorisation). This implies that the applicants need to meet the “‘general” standing requirements and, consequently, to prove individual and direct concern.

According to the orthodox interpretation of the concept of individual concern, an applicant would have to prove that he belongs to a closed class and is affected by the measure in the same way as the addressee.Footnote 87 This is possible for the marketing authorisation applicant, given that he is concerned by the measure in a different way than other market participants, as he is the initiator of the marketing authorisation procedure and, through the composition of the dossier, influences its content. Furthermore, the marketing authorisation applicant will also be able to prove direct concern as the final national measure “directly affect[s] the legal situation of the individual and leave[s] no discretion to the addressees of that measure who are entrusted with the task of implementing it, such implementation being purely automatic and resulting from Community rules without the application of other intermediate rules”.Footnote 88

However, proving individual concern is improbable at best for competitors, seeing that individual concern has not been recognised in situations concerning “a commercial activity which may at any time be practised by any person”.Footnote 89 As far as associations are concerned, it is settled case law that these actions are only admissible in three situations:Footnote 90 (a) when a legal provision grants procedural rights to these associations;Footnote 91 (b) where every single member of the association would be directly and individually concerned;Footnote 92 and (c) where the association’s interests, and especially its position as a negotiator, is affected by the measure.Footnote 93 Considering that none of these conditions are met in the case of marketing authorisations for pharmaceuticals, the competitor and the association are not likely to be able to prove individual concern. The only possibility for them, therefore, is to wait until there is a final decision by a national authority, bring a claim against this measure, and ask the national court to ask a preliminary question of validity under Article 267 TFEU.

In conclusion, in the supra-national arbitration phase, the referral of the procedure to EMA cannot be challenged, while EMA’s opinion and the surrounding input could be challenged together with the final Commission Implementing Decision. The Commission Implementing Decision can be challenged by the applicant via an action for annulment – a route which is however closed for competitors and civil society organisations. The latter groups of applicant may only challenge the Commission Implementing Decision indirectly through a preliminary question of validity against the final national measure concluding the decision-making process.

2. Centralised Procedure

As mentioned above, the Centralised Procedure starts with a submission of an application to the EMA and then it follows the same steps of the supranational arbitration phase (in terms of the engagement of EMA and the relevant comitology committee), except that there is no final national measure at the end of decision-making process, but the marketing authorisation (or its denial) is contained in a Commission Implementing Decision addressed to the applicant.

With regard to the reviewability of EMA’s opinion, the same considerations made above apply. With regard to the final Commission decision in the Centralised Procedure, it should initially be pointed out that there are two main differences between the measure issued by the Commission in the Centralised Procedure and the Commission’s engagement in the Mutual Recognition and Decentralised Procedures. First, in terms of the addressees of the Commission’s action, in the first case the decision is addressed to the Member States, while in the second it is addressed to the applicant. Secondly, while in the first case the Commission decision is itself a step in the decision-making process which is concluded at the national level, in the second case the Commission Implementing Decision is the final step in the decision-making procedure.

However, these two differences have no impact for the purposes of the rules on standing. First of all, as regards the marketing authorisation applicant, the fact that the Commission Implementing Decision in the centralised procedure is addressed to the operator means that he will be able to challenge the measure under an action for annulment. Secondly, with regard to competitors and associations, as in the case examined above, this Commission Implementing Decision cannot be qualified as a measure of general application, and hence is not a regulatory act for the purposes of Article 263 TFEU. As consequence, competitors and associations do need to prove individual and direct concern, which, for the reasons highlighted above, seems improbable at best.

In conclusion, in cases concerning the Centralised Procedure, the applicant will be able to challenge the final Commission Implementing Decision, and, through that, also EMA’s opinion, while competitors and associations will have a hard time proving individual concern.

IV. Conclusion and possible solutions

The analysis above has shown that, in the area of pharmaceuticals, the complex authorisation routes, which form a curious mix of direct, indirect and composite administration, mean that the judicial protection that is granted is heavily dependent on the applicable procedure and the question of the degree to which Member States can agree upon a positive evaluation. First of all, the choice of procedure is very much dictated by the nature of the product and targeted markets. Then, if the mutual recognition or decentralised procedural route is chosen, for one and the same product and the same type of decision requested (a marketing authorisation), the judicial review possibilities depend on the ability of the Member States to find consensus during the procedure, which is beyond the control of the marketing authorisation applicant. This roulette wheel of access to judicial review is even more pronounced for competitors and public interest organisations, who are mere bystanders during the procedure.

Furthermore, the analysis above has revealed that gaps in judicial reviewability almost only arises in cases of “truly” composite procedures, while in the national procedure no problem of judicial protection arises due to the absence of multi-level activity. Also in the Centralised Procedure, the only gap identified is the lack of standing of competitors and associations, but this is caused by the Plaumann doctrine and the restrictive interpretation by the CJEU of the notion of “individual concern” rather than the composite nature of the procedure.

Thirdly, it has been shown that, in “truly” composite procedures (namely the Decentralised and the Mutual Recognition Procedures), intermediate procedural steps are hardly challengeable at any level: firstly, because of the strict duality of jurisdiction, and the fact that the systems of judicial review are not geared towards the multi-level nature of decision-making. Secondly, the gaps of judicial protection arise due to the hybridity of certain bodies involved in the process (this is the case with the CMDh, whose actions are not reviewable at national level and may not be reviewable at EU level).

These challenges are systemic in the composite nature of EU administration and difficult to address. One ideal improvement would be the introduction of horizontal and reverse preliminary ruling systems. In this way the court of the measure which concludes the process could ask a question of validity to the courts of the system of the intermediate measures. Such a system of preliminary rulings would allow for validity questions to be dealt with by the judicial system in which the measures originate, which would address the concern that judicial review of preparatory measures in composite procedures is inconceivable due to the extraterritorial effects and problems in enforcement of such decisions.Footnote 94 One could also question whether national courts should disregard the orthodox territoriality principle which prevents them from reviewing foreign administrative action, and should be put in a position where they are able to review measures originating in other Member States’ administration, regarding their validity under EU law.Footnote 95 However, this possibility would create serious legal certainty problems, as the foreign can certainly not be annulled by the courts of another legal system, but, at most, set aside inter partes. For this reason, albeit rather implausible for political reasons, a system of horizontal preliminary rulings would be preferable if the system of judicial protection is to become “integrated” as the system of administrative decision-making.