Introduction

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a disabling and chronic condition characterized by persistent and unwanted intrusive thoughts, images and urges (obsessions) and repetitive behaviors or mental acts (compulsions) (American Psychiatrc Association, 2013). Even though OCD has been historically considered rare in youth (Geller, Reference Geller2006), more recent evidence suggests that OCD is actually one of the most common psychiatric disorders in childhood, with an estimated prevalence of 0.25% – 4% among children and adolescents (Krebs & Heyman, Reference Krebs and Heyman2015). In this regard, OCD characteristically presents two peaks of incidence: an early peak with a mean age of 9 to 10 years (with an SD of± 2.5 years) and a later peak in the early 20s (Geller et al., Reference Geller, Biederman, Faraone, Frazier, Coffey, Kim and Bellordre2000).

Childhood OCD is physio-pathologically related to a broader constellation of restricted and repetitive behaviors (RRBs), characterized by repetition and invariance (e.g., motor stereotypies, ritualistic behaviors, rigid and inflexible routines, circumscribed and intense interests or activities), which represents a normal behavioral repertoire in early childhood (De Caluwé et al., Reference De Caluwé, Vergauwe, Decuyper, Bogaerts, Rettew and De Clercq2020). During development, obsessive-compulsive symptoms (OCS) are a core behavioral phenotype of many etiologically defined or idiopathic neurodevelopmental disorders (Wolff et al., Reference Wolff, Boyd and Elison2016), whereas longitudinally they are associated with an increased risk of severe psychiatric conditions in adulthood (Micali et al., Reference Micali, Heyman, Perez, Hilton, Nakatani, Turner and Mataix-Cols2010), including both major endogenous psychoses (Cederlöf et al., Reference Cederlöf, Lichtenstein, Larsson, Boman, Rück, Landén and Mataix-Cols2015).

Therefore, despite the robust epidemiological evidence, three major challenges concern the theoretical conceptualization and clinical identification of childhood OCD. 1) Its relationship (continuity/discontinuity) with normal patterns of ritualistic/routinized behaviors in typically developing children. 2) The synchronic association with different neurodevelopmental disorders. 3) The diachronic association with both affective and non-affective psychoses in late adolescence/early adulthood.

From a developmental perspective, childhood OCD appears in continuity with normative RRBs, from which OCS would stem following an altered trajectory relative to the expected pattern, particularly for those children with or at risk of various neurodevelopmental perturbations (Wolff et al., Reference Wolff, Boyd and Elison2016), with a profound impact on the maturation of sensorimotor connectivity (Cascio, Reference Cascio2010). The study hypothesis is that childhood OCD may at least in part reflect a developmental heterochronic shift of behavioral phenotypes characteristic of all children during specific brain maturation stages, triggered by different sources of sensory unbalance. In this regard, epigenetic regulation might mediate the relationship between the lack of attenuation of compulsive-like behaviors and sensorimotor dysconnectivity. During development, in fact, behavioral outputs are strongly shaped by epigenetic changes (Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Lussier, Smith, Simpkin, Suderman, Walton, Relton and Dunn2022). In particular, during brain maturation stages, which extend from about three weeks after conception throughout childhood and adolescence, sensorimotor connectivity patterns are characterized by rapidly forming, plastic circuits, which heavily depend on epigenetic modifications (Murgatroyd & Spengler, Reference Murgatroyd and Spengler2012). In turn, epigenetic regulation is highly susceptible to influences from prenatal or postnatal experiences and may be transient or persist throughout a lifetime (Weaver et al., Reference Weaver, Cervoni, Champagne, D’Alessio, Sharma, Seckl, Dymov, Szyf and Meaney2004).

The present study aims to offer a working hypothesis on the epigenetic and developmental mechanisms beneath OCD in youth within an evolutionary framework, to grasp the clinical significance and ultimate causes of compulsive-like rituals in childhood and, in particular, to investigate a putative role of OCS as early and reliable biomarkers of different neurodevelopmental conditions. Improved characterization of developmental trajectories of childhood OCD might in fact contribute to better identify at-risk children and delineate clinically meaningful subgroups based on shared and specific phenotypes.

Methods

Given the specific clinically-tailored scope, a narrative review on the different and articulated aspects of the hypothesis proposed was considered more suited than a systematic review. The Web of Science and PubMed databases were searched for articles that met these issues, using a range of related search terms and cited papers within salient articles. Searches were performed in titles and abstracts, using keywords grouped under two blocks separated by ‘AND’. In particular, articles were searched with the following keywords: (“restricted and repetitive behaviors” or “rituals” or “obsessive-compulsive disorder”) AND (“children” or “adolescents”); (“obsessive-compulsive disorder”) AND (“epigenetics” or “sensory phenomena” or “neurocognition”). The search was conducted in February 2023 and updated in September 2024.

The first author screened all articles based on title (and abstract). Irrelevant articles were excluded, i.e., if they: 1) did not focus on normative rituals/routines or OCD/OCS; 2) did not address younger age groups; 3) were not peer-reviewed articles or did not have a full-text version (e.g., meeting abstracts or expert opinions); 3) were not conducted in humans; 4) had no English full text. To test objectivity and inter-rater agreement, the second author independently screened 10% of the articles based on title (and abstract).

Findings are organized in the following sections related to childhood OCD: relationship with normative rituals, specific comorbidity profile, sensory phenomena, neurocognitive profile, epigenetic mechanisms. In the final section, clinical, psychopathological, neurophysiological and epigenetic data are integrated and discussed together to propose a coherent evolutionary and developmental hypothesis of childhood OCD.

Normative rituals and childhood OCD

From the age of two, RRBs are included in the normal behavioral pattern of young children: complex rituals, particularly at times of transitions (e.g., mealtime, bedtime, bath), are reported in around 80% of toddlers and preschool children (Evans et al., Reference Evans, Leckman, Carter, Reznick, Henshaw, King and Pauls1997; Leonard et al., Reference Leonard, Goldberger, Rapoport, Chelsow and Swedo1990). Rigid adherence to “just right” or sameness in daily routines, as well as hyper-attention to minute details such as imperfections or peculiarities in clothes and toys are common features of these compulsive-like behaviors (Evans & Maliken, Reference Evans and Maliken2011). Interestingly, there seems to be a specific temporal window for normative rituals during development, with a peak between the ages of 2–6, followed by a linear decline around the age of 7 (Glenn et al., Reference Glenn, Cunningham and Nananidou2012). It has been argued that RRBs have an adaptive significance in early childhood, as they give order and predictability over daily life contingencies (Evans & Maliken, Reference Evans and Maliken2011). This is in accordance with the common evidence that rituals in youth are preferentially triggered by abrupt changes in the physical environment or in the daily routine, that are experienced by young children as essentially chaotic or uncontrollable (Zohar & Felz, Reference Zohar and Felz2001). Following the development of executive function skills along with the maturation of the prefrontal cortex, children gradually abandon RRBs, which no longer constitute an age-appropriate response, to rely on more flexible and contextual coping mechanisms (Zohar & Dahan, Reference Zohar and Dahan2016).

Ultimately, RRBs appear to constitute a developmentally normative and roughly normally distributed behavioral trait in earlier years (Bolton et al., Reference Bolton, Rijsdijk, Eley, O’Connor, Briskman and Perrin2009). Therefore, the question arises as to whether RRBs are qualitatively different phenotypic expressions from childhood OCD or, rather, whether RRBs and OCD lie on a continuum, with shared pathophysiological underpinnings. In this regard, a recent systematic review (De Caluwé et al., Reference De Caluwé, Vergauwe, Decuyper, Bogaerts, Rettew and De Clercq2020) supports a continuity model from RRBs to OCS in pediatric age. Normative and OCD rituals present in fact common phenotypic features, with a fixed package of themes, which reflect an underlying dimensional architecture (Barahona-Corrêa et al., Reference Barahona-Corrêa, Camacho, Castro-Rodrigues, Costa and Oliveira-Maia2015). Interestingly, in normative rituals, this set of contents or dimensions is age-dependent, as it changes over time as a function of varying developmental salience (Laing et al., Reference Laing, Fernyhough, Turner and Freeston2009), whereas in OCD, it becomes increasingly less developmentally appropriate when children get older (Evans et al., Reference Evans, Gray and Leckman1999). The specific temporal pattern in which RRBs and OCD follow one another (a decline of RRBs around the age of 7 with a subsequent onset of OCD-like behavior, the contents of which become increasingly more decontextualized with age) hints at a continuity between the two (De Caluwé et al., Reference De Caluwé, Vergauwe, Decuyper, Bogaerts, Rettew and De Clercq2020). This would be further corroborated by the evidence that high levels of normative rituals constitute a risk factor for developing OCD (Zohar and Felz, Reference Zohar and Felz2001). In this vein, Zohar and Dahan (Reference Zohar and Dahan2016) found that in 1345 community children (2–6 years old), more pronounced RRBs were related to typical maladaptive OCD characteristics, such as fears, negative-emotional temperament and emotional dysregulation. Remarkably, similar behavioral and emotional profiles run parallel with similar neurocognitive patterns. Evidence in fact indicates a shared neurocognitive background for RRBs and OCD in terms of impaired motor-suppression, motor inhibition and set-shifting deficits (Evans et al., Reference Evans, Lewis and Iobst2004; Pietrefesa & Evans, Reference Pietrefesa and Evans2007; Zohar and Dahan, Reference Zohar and Dahan2016). Finally, only one study (Bolton et al., Reference Bolton, Rijsdijk, Eley, O’Connor, Briskman and Perrin2009) investigated whether the relationship between RRBs and OCD may be genetically mediated. The authors found in 4662 twin-pairs of 6 years old a significant correlation between RRBs and OCD symptoms, of which half of the variance (55%) was attributable to genetic effects. In sum, shared phenotypic, neurocognitive and genetic data suggest a continuity between adaptive RRBs and maladaptive OCD (De Caluwé et al., Reference De Caluwé, Vergauwe, Decuyper, Bogaerts, Rettew and De Clercq2020).

Coherently, neurophysiological and neurobiological evidence would confirm a continuity in neural processing beneath the normative and pathological aspects of ritual behavior, mediated by connectivity refinement of cortico-striatal pathways during development (Evans & Maliken, Reference Evans and Maliken2011; Graybiel, Reference Graybiel2008). In particular, discrete and parallel neural systems within the cortico-striato-thalamocortical circuitry (CSTC) would represent the neural scaffolding for the distinct dimensions of ritual contents (Mataix-Cols et al., Reference Mataix-Cols, Wooderson, Lawrence, Brammer, Speckens and Phillips2004). Across vertebrate phylogeny, different inborn or learned habitual and routinized motor patterns are encoded and packaged as units ready for expression in basal ganglia loops (Graybiel, Reference Graybiel2008). Therefore, CSTC networks represent a repository for ’species-typical’ daily master routines, habits and rituals (Ploog, Reference Ploog2003). These cyclic, species-specific, action strategies are expressed depending on age in normative rituals (Pietrefesa & Evans, Reference Pietrefesa and Evans2007), whereas they appear excessive and/or temporally mismatched in OCD (Thorn et al., Reference Thorn, Atallah, Howe and Graybiel2010).

Altogether, compulsive-like rituals represent a genetically preprogramed behavioral response, with an important adaptive value in early childhood, but also with an adverse functional impact if they inappropriately persist over time and/or are excessively released (Rapoport et al., Reference Rapoport, Swedo, Leonard, Rutter, Taylor and Hersov1994). Of course, compulsive rituals far from representing purely behavioral expressions, also involve specific emotional and cognitive domains, which are inextricably intertwined. In fact, the highly conserved CSTC loops participate in complex mutual interactions with other functional networks (Stein et al., Reference Stein, Costa, Lochner, Miguel, Reddy, Shavitt, van den Heuvel and Simpson2019). Indeed, the dense connections and functional organizations of the basal ganglia place them in a privileged position to exert a broad coordinating influence on cognitive and emotion processing as well (Pierce & Péron, Reference Pierce and Péron2020). In this regard, Shephard and colleagues (Shephard et al., Reference Shephard, Stern, van den Heuvel, Costa, Batistuzzo, Godoy, Lopes, Brunoni, Hoexter, Shavitt, Reddy, Lochner, Stein, Simpson and Miguel2021) distinguish the following main neurocircuits in OCD: 1) Fronto-limbic circuit, with a pivotal role in emotional processing; 2) Sensorimotor circuit, involved in the generation and control of motor behavior and integration of sensory information; 3) Ventral cognitive circuit, responsible for self-regulatory behaviors; 4) Ventral affective circuit, involved in reward-related processing; 5) Dorsal cognitive circuit, underpinning executive functions for goal-directed behaviors. Abnormalities in these neurocircuits, deeply interconnected with basal ganglia loops, underlie the complex phenotypic expression of OCD.

Comorbidity pattern of childhood OCD

Compulsive-like behaviors not only occur during normative childhood development but also are comorbid with a widespread spectrum of etiologically different neuropsychiatric conditions, including neurodevelopmental disorders, neurocognitive impairments and neurogenetic syndromes (De Caluwé et al., Reference De Caluwé, Vergauwe, Decuyper, Bogaerts, Rettew and De Clercq2020). Moreover, compulsive-like rituals have been described in both internalizing and externalizing psychiatric disorders in infancy (Evans et al., Reference Evans, Uljarević, Lusk, Loth and Frazier2017; Peris et al., Reference Peris, Rozenman, Bergman, Chang, O’Neill and Piacentini2017).

It is often difficult to disentangle “true” compulsive rituals from a broader bunch of restricted and repetitive behaviors, which co-occur in comorbid neurodevelopmental conditions. For example, RRBs are also a core diagnostic feature of autism spectrum disorders (ASD) (Comparan-Meza et al., Reference Comparan-Meza, Vargas de la Cruz, Jauregui-Huerta, Gonzalez-Castañeda, Gonzalez-Perez and Galvez-Contreras2021) and may phenotypically result in compulsive-like behavioral outcomes. Moreover, in both OCD and ASD repetitive behaviors seem to be specifically triggered by distressing sensory experiences as a way to restore a sensory balance (Jiujias et al., Reference Jiujias, Kelley and Hall2017). Consistently, prevalence rates of OCD are significantly elevated among individuals with ASD and further complicate efforts to distinguish between disorder-specific symptoms (Simonoff et al., Reference Simonoff, Pickles, Charman, Chandler, Loucas and Baird2008). Other highly prevalent comorbidities are tic disorders and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Up to 59% of children and adolescents with OCD meet the criteria for a diagnosis of a tic disorder at some point during their lifetime (Leonard et al., Reference Leonard, Lenane, Swedo, Rettew, Gershon and Rapoport1992), whereas co-morbid ADHD occurs with a prevalence estimate of 25.5% (Masi et al., Reference Masi, Millepiedi, Perugi, Pfanner, Berloffa, Pari, Mucci and Akiskal2010). Regardless of the underlying comorbid condition, the developmental trajectories of this group of behaviors follow a relatively predictable course: their presentation tends to become more cognitively articulate over time, with compulsive symptoms more pronounced in pediatric age and obsessive symptoms more severe in adults (Farrell et al., Reference Farrell, Barrett and Piacentini2006; Selles et al., Reference Selles, Storch and Lewin2014).

An exhaustive examination of the different kinds of comorbidity goes beyond the aim of the present study. It should be noted however that RRBs, normative in early childhood, seem to persist and/or to exacerbate, instead of decreasing over time, whenever an underlying neurodevelopmental perturbation occurs, regardless of a specific etiology (De Caluwé et al., Reference De Caluwé, Vergauwe, Decuyper, Bogaerts, Rettew and De Clercq2020). In this connection, also childhood adversities, such as trauma exposure (be it physical, sexual or emotional; abuse or neglect) might play a moderating role, with a triggering and/or cumulative effect over the neurodevelopmental background (Park et al., Reference Park, Hong, Bae, Cho, Lee, Lee, Chang, Jeon, Hahm, Lee, Seong and Cho2014). Indeed, 50–70% of OCD patients report childhood traumatic experiences prior to the onset of OCD symptoms (Dykshoorn, Reference Dykshoorn2014). Noteworthy, childhood trauma seems to be more related to compulsive behaviors than “pure” obsessions, suggesting that traumatic experiences may preferentially trigger a motor/behavioral response, innate in origin, to avoid intrusive trauma-related emotions and thoughts (Miller & Brock, Reference Miller and Brock2017).

Childhood OCD and vulnerability to adult psychoses

If we turn the attention to diachronic comorbidities of childhood OCD, a primary diagnosis of OCD is associated with an increased risk of receiving a later diagnosis of one of the two major endogenous psychoses: schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (Cederlöf et al., Reference Cederlöf, Lichtenstein, Larsson, Boman, Rück, Landén and Mataix-Cols2015). As to the former, in an 11-year follow-up study on 35,255 adolescents and adults with OCD (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Tsai, Liang, Cheng, Su, Chen and Bai2023), the progression rate from OCD to schizophrenia totaled 7.80%. In this respect, the childhood onset of OCD appears as a specific indicator of schizophrenia vulnerability (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Chen, Yang, Chen, Lee and Lu2019; Meier et al., Reference Meier, Petersen, Pedersen, Arendt, Nielsen, Mattheisen, Mors and Mortensen2014; Van Dael et al., Reference Van Dael, van Os, de Graaf, ten Have, Krabbendam and Myin-Germeys2011). Accordingly, Borrelli and colleagues (Borrelli et al., Reference Borrelli, Ottoni, Provettini, Morabito, Dell’Uva, Marchesi and Tonna2024a) showed that the likelihood of developing schizophrenia in outpatients with a primary diagnosis of OCD gradually increased in parallel to the lowering in the age of OCD onset, with very-early onset OCD (< 10 years) presenting the highest rates of pre-psychotic symptoms. In particular, children and adolescents with a primary diagnosis of OCD and at risk for psychosis present with a specific OCD profile: 1) earlier age of OCD onset; 2) more severe OCS; 3) prominent compulsions (mainly washing compulsions); 4) poorer global functioning (Borrelli et al., Reference Borrelli, Cervin, Ottoni, Marchesi and Tonna2023). Overall, these findings would support the hypothesis that in children with OCD, a specific OCD phenotype may actually cover an underlying vulnerability for the schizophrenia spectrum. In this regard, childhood trauma experiences might play a crucial role in the transition toward full-blown psychosis, as they appear to predict either more severe OCD or pre-psychotic symptoms in the OCD pediatric population (Borrelli et al., Reference Borrelli, Dell’Uva, Provettini, Gambolò, Di Donna, Ottoni, Marchesi and Tonna2024b).

Less studied, on the contrary, is the relationship between childhood OCD and bipolar vulnerability. However, there is evidence that OCD in childhood and adolescence increases the risk of a later diagnosis of bipolar disorder (BD) (Cederlöf et al., Reference Cederlöf, Lichtenstein, Larsson, Boman, Rück, Landén and Mataix-Cols2015; D’Ambrosio et al., Reference D’Ambrosio, Albert, Bogetto and Maina2010). In this respect, in more than 60% of OCD-BD patients, OCS precede the onset of BD (Tonna et al., Reference Tonna, Amerio, Odone, Stubbs and Ghaemi2016a). After BD onset, OCS would initially coexist with BD symptoms and then gradually decrease in adulthood (Amerio et al., Reference Amerio, Stubbs, Odone, Tonna, Marchesi and Nassir Ghaemi2016).

Therefore, childhood OCD not only frequently co-occurs with various neurodevelopmental disorders but may also cover the developmental trajectories of severe psychiatric conditions (both affective and non-affective psychoses), which will arise later, in late adolescence or early adulthood (Tonna et al., Reference Tonna, Amerio, Ottoni, Paglia, Odone, Ossola, De Panfilis, Ghaemi and Marchesi2015).

Sensory phenomena in childhood OCD

Since childhood, OCD patients typically perceive a broad range of mental and bodily experiences, often referred to as “sensory phenomena” (Cervin, Reference Cervin2023; Moreno-Amador et al., Reference Moreno-Amador, Cervin, Martínez-González and Piqueras2023; Poletti et al., Reference Poletti, Gebhardt, Pelizza, Preti and Raballo2023; Schreck et al., Reference Schreck, Georgiadis, Garcia, Benito, Case, Herren, Walther and Freeman2021). Mental sensory phenomena (e.g., “just-right perceptions,” “feelings of incompleteness,” and “not just-right experience”) generally involve feelings of discomfort that something is not right. Remarkably, such experiences normally precede, trigger or accompany repetitive behaviors, thus representing the subjective scaffolding for compulsions, which are performed to regain a feeling of control and order (Ferrão et al., Reference Ferrão, Shavitt, Prado, Fontenelle, Malavazzi, de Mathis, Hounie, Miguel and do Rosário2012; Prado et al., Reference Prado, Rosário, Lee, Hounie, Shavitt and Miguel2008). Bodily sensory phenomena refer to a variety of physical sensitivities (e.g., intolerance of innocuous sounds such as breathing, rubbing, or sniffing; extreme sensitivity to loud auditory stimuli), underlying a sensory over-responsivity to external stimuli (Ben-Sasson & Podoly, Reference Ben-Sasson and Podoly2017). Moreover, according to the “Seeking Proxies for Internal States” model (Dar et al., Reference Dar, Lazarov and Liberman2021), OCD patients also present impaired access to their somatosensory states (including emotions, bodily states and sensations), with the tendency to rely on external “proxies” (i.e., verifiable indices of internal state), which then take the form of rigid rules, rituals or routines.

Few studies to date have attempted to investigate the neuroanatomical substrate of sensory phenomena in people with OCD (Cervin & Borrelli, Reference Cervin, Borrelli, Guzick and Storch2025). Sensory phenomena have been found associated with gray matter volume increases within the sensorimotor cortex (Subirà et al., Reference Subirà, Sato, Alonso, do Rosário, Segalàs, Batistuzzo, Real, Lopes, Cerrillo, Diniz, Pujol, Assis, Menchón, Shavitt, Busatto, Cardoner, Miguel, Hoexter and Soriano-Mas2015). In particular, mental sensory phenomena appear related to increased activation in the left mid-posterior insula as well as somatosensory, mid-orbitofrontal, and lateral prefrontal cortical activity (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Shahab, Collins, Fleysher, Goodman, Burdick and Stern2019). OCD sensory over-responsivity would be specifically linked to orbitofrontal pathways, which play a key role in processing the value and consequences of sensory stimulation (Cervin, Reference Cervin2023; Collins et al., Reference Collins, Recchia, Eng, Harvey, Tobe and Stern2024). Altogether, sensory phenomena in people with OCD are related to brain circuits involved in sensorimotor processing and in the integration of sensory information (Van Hulle et al., Reference Van Hulle, Esbensen and Goldsmith2019). This is consistent with the hypothesis that OCD, and particularly compulsive behavior, may be associated with hypo-functioning of sensory gating (Rossi et al., Reference Rossi, Bartalini, Ulivelli, Mantovani, Di Muro, Goracci, Castrogiovanni, Battistini and Passero2005) and/or a dysfunction of sensorimotor integration (Russo et al., Reference Russo, Naro, Mastroeni, Morgante, Terranova, Muscatello, Zoccali, Calabrò and Quartarone2014).

Sensory phenomena have been repeatedly found in youth with OCD dispositions, thus appearing as a trait-like condition (Cervin, Reference Cervin2023; Van Hulle et al., Reference Van Hulle, Esbensen and Goldsmith2019). For example, there is evidence for a strong relationship between oral and tactile hypersensitivity and the severity of compulsive-like behaviors in pediatric age as well as with OCD severity later in life (Bart et al., Reference Bart, Bar-Shalita, Mansour and Dar2017; Dar et al., Reference Dar, Kahn and Carmeli2012). In other words, at least a subgroup of pediatric OCD patients presents with symptoms that are primarily triggered by sensorimotor stimuli, where perceptions, sensations and urges actually precede repetitive behaviors (Tal et al., Reference Tal, Cervin, Liberman and Dar2023). Therefore, it is possible to speculate a link between multisensory disruption and compulsive-like behavior in developmental years. It has been hypothesized that imparting a sense of control via rituals helps to overcome sensory-related issues (Dar et al., Reference Dar, Kahn and Carmeli2012; Lidstone et al., Reference Lidstone, Uljarević, Sullivan, Rodgers, McConachie, Freeston, Le Couteur, Prior and Leekam2014). In this connection, compulsive behavior would represent a coping mechanism to regain a sensory balance over a condition of sensorial unpredictability (Bart et al., Reference Bart, Bar-Shalita, Mansour and Dar2017; Jiujias et al., Reference Jiujias, Kelley and Hall2017). Both motor and cognitive pathways may be involved: on the one hand, repetitive and rigid physical actions per se reduce physiological arousal due to anxiety-related unpredictability (Anderson & Shivakumar, Reference Anderson and Shivakumar2013; Karl & Fischer, Reference Karl and Fischer2018; Lang et al., Reference Lang, Krátký, Shaver, Jerotijević and Xygalatas2015). On the other, hyperattention to the reordering sequence of ritual acts (repetition, specific number of procedural steps, and time specificity) leads to the subjective perception of a “reordered” world (Legare & Souza, Reference Legare and Souza2012). Therefore, the sensorimotor experience of engaging in sequenced actions that are rigid, formal, and repetitive, coupled with the motor control required to enact these actions, allows regaining a feeling of stability and predictability in the perceptual experience (Tonna et al., Reference Tonna, Ottoni, Pellegrini, Mora, Gambolo, Di Donna, Parmigiani and Marchesi2022). From this perspective, it is possible to assume that childhood compulsions may represent a developmental adaptive response to sensory phenomena stemming from primary difficulty in modulating sensory input.

Neurocognitive endophenotypes of childhood OCD

An early perturbation of multisensory integration has also a relevant impact on neurocognitive development (Dionne-Dostie et al., Reference Dionne-Dostie, Paquette, Lassonde and Gallagher2015). Unfortunately, to date research on a specific neurocognitive profile in childhood OCD is limited and has yielded variable results (Abramovitch et al., Reference Abramovitch, Abramowitz, Mittelman, Stark, Ramsey and Geller2015).

In childhood, more promising seems to be the search for candidate neurocognitive endophenotypes (Chamberlain and Menzies, Reference Chamberlain and Menzies2009). An endophenotype is a heritable quantitative trait that correlates with an increased genetic susceptibility to a disorder; it is co-inherited with the disease and can be detected in unaffected first-degree relatives. As such, endophenotypic traits may manifest long before the onset of the disorder (Gottesman and Gould, Reference Gottesman and Gould2003). In this regard, Chamberlain and Menzies (Reference Chamberlain and Menzies2009) identified several potential cognitive endophenotypes in OCD, including motor inhibition, cognitive flexibility, decision-making, action monitoring, reversal learning and memory. In this vein, a recent systematic review by Marzuki et al. (Reference Marzuki, Pereira de Souza, Sahakian and Robbins2020) confirmed in youth OCD patients robust increases in brain error related negativity associated with abnormal action monitoring, impaired decision-making under uncertainty, planning, and visual working memory. A recent study (Uhre et al., Reference Uhre, Ritter, Jepsen, Uhre, Lønfeldt, Müller, Plessen, Vangkilde, Blair and Pagsberg2024) found in children with OCD specific impairments in cognitive flexibility, decision-making, working memory, and processing speed.

However, only few studies have examined cognitive function in pediatric OCD patients and their unaffected relatives. Negreiros et al. (Reference Negreiros, Belschner, Best, Lin, Franco Yamin, Joffres, Selles, Jaspers-Fayer, Miller, Woodward, Honer and Stewart2020) found that youth with OCD and unaffected siblings performed significantly worse in planning ability compared to healthy controls. In a large, rigorously screened cohort of pediatric OCD probands, their unaffected siblings, and parents, Abramovitch et al. (Reference Abramovitch, De Nadai and Geller2021) identified deficits in the specific subdomains of cognitive flexibility and inhibitory control (i.e., proactive control and initial concept formation) across all three groups, proposing them as valid endophenotypes in pediatric OCD. The next step should be to investigate whether these traits are associated with specific candidate genes, so to unravel the developmental interplay between endophenotypes, genetic factors and environmental influences, in the progression towards OCD (Marzuki et al., Reference Marzuki, Pereira de Souza, Sahakian and Robbins2020).

Epigenetic mechanisms of OCD

Data from twin, family and segregation studies strongly support a genetic component of OCD (for a comprehensive summary, see Blanco-Vieira et al., Reference Blanco-Vieira, Radua, Marcelino, Bloch, Mataix-Cols and do Rosário2023). The genetic influence on OCD is polygenic, with many genes involved (in particular, within the serotonergic, dopaminergic and glutamatergic systems), which individually exert a relatively small effect on the phenotype (Krebs & Heyman, Reference Krebs and Heyman2015). Although existing literature has yielded important insight into the genetic basis of OCD (Mahjani et al., Reference Mahjani, Bey, Boberg and Burton2021), the investigation of epigenetic changes might be a crucial point to understand the developmental trajectories of OCD psychopathology. On the one hand, there is increasing evidence that environmental factors have a prominent role in OCD onset (Grünblatt et al., Reference Grünblatt, Marinova, Roth, Gardini, Ball, Geissler, Wojdacz, Romanos and Walitza2018; Mataix-Cols et al., Reference Mataix-Cols, Boman, Monzani, Rück, Serlachius, Långström and Lichtenstein2013; Pauls et al., Reference Pauls, Abramovitch, Rauch and Geller2014); on the other, different environmental factors have been found to play a role in epigenetic modification (Essex et al., Reference Essex, Thomas Boyce, Hertzman, Lam, Armstrong, Neumann and Kobor2013; Parade et al., Reference Parade, Huffhines, Daniels, Stroud, Nugent and Tyrka2021). In this direction, epigenetics may represent the interface between environmental events resulting in alterations in gene expressions (Mohammadi et al., Reference Mohammadi, Karimian, Mirzaei and Milajerdi2023).

The term “epigenetics” refers to heritable modifications that alter gene function without changing the DNA sequence. At the molecular level, these mechanisms, able to affect the phenotype without altering the genotype, include DNA methylation, histone modifications and variants, chromatin remodeling, and non-coding RNA, which work together to control DNA packaging and gene regulation and ensure genomic stability (Feng et al., Reference Feng, Fouse and Fan2007). In addition to genetic factors (Gerra et al., Reference Gerra, Gerra, Tadonio, Pellegrini, Marchesi, Mattfeld, Gerra and Ossola2021; Takesian & Hensch, Reference Takesian and Hensch2013), these epigenetic mechanisms are actively at work in shaping neural connectivity during sensitive periods (Dunn et al., Reference Dunn, Soare, Zhu, Simpkin, Suderman, Klengel, Smith, Ressler and Relton2019; Nagy & Turecki, Reference Nagy and Turecki2012; Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Lussier, Smith, Simpkin, Suderman, Walton, Relton and Dunn2022). In this regard, different developmental factors, including childhood adverse experiences, which occur in sensitive periods as developmental stages, heavily influence synaptic plasticity and thus neurobiological and behavioral outcomes (Krause et al., Reference Krause, Artigas, Sciolla and Hamilton2020; Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Lussier, Smith, Simpkin, Suderman, Walton, Relton and Dunn2022). Similarly, growing evidence is unraveling the association between alterations in epigenetic signatures and neurodevelopmental disorders (Jobe et al., Reference Jobe, McQuate and Zhao2012; Murgatroyd & Spengler, Reference Murgatroyd and Spengler2012). Consistently, the search for possible associations between epigenetic changes and psychopathology, how these alterations may persist during development and potential reversal strategies is increasingly becoming a focal point for different psychiatric conditions, including OCD (Bagot et al., Reference Bagot, Labonté, Peña and Nestler2014; Dunn et al., Reference Dunn, Soare, Zhu, Simpkin, Suderman, Klengel, Smith, Ressler and Relton2019; Lewis & Olive, Reference Lewis and Olive2014; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Hu, Benedek, Fullerton, Forsten, Naifeh, Li, Li, Benevides, Smerin, Le, Choi and Ursano2014). However, the individuation of putative epigenetic risk factors in OCD onset is still at a preliminary stage (for a comprehensive summary, see Mohammadi et al., Reference Mohammadi, Karimian, Mirzaei and Milajerdi2023).

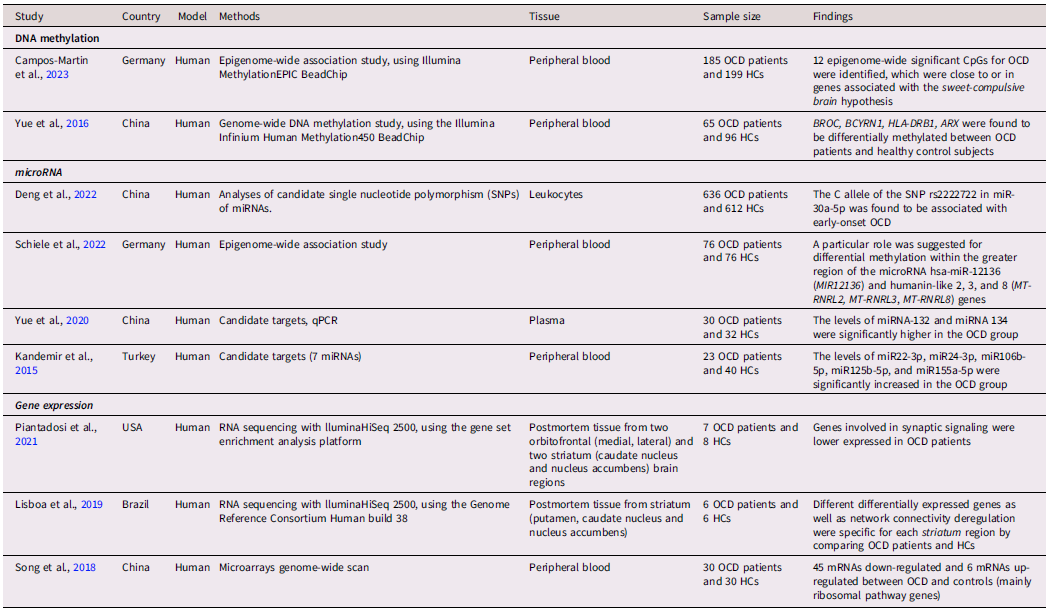

Candidate epigenetic OCD studies have initially focused on the potential contribution of DNA methylation alterations in specific gene regions or CpG dinucleotides. DNA methylation, consisting of the methyl group addition in cytosine nucleotides occurring next to a guanine nucleotide, is involved in gene regulation (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Tsai, Liang, Cheng, Su, Chen and Bai2023; Ma et al., Reference Ma, Jang, Guo, Kitabatake, Chang, Pow-anpongkul, Flavell, Lu, Ming and Song2009; Martinowich et al., Reference Martinowich, Hattori, Wu, Fouse, He, Hu, Fan and Sun2003), memory and learning (Day & Sweatt, Reference Day and Sweatt2010; Muotri et al., Reference Muotri, Marchetto, Coufal, Oefner, Yeo, Nakashima and Gage2010), and transcriptional processes in the central nervous system (CNS) (Muotri et al., Reference Muotri, Marchetto, Coufal, Oefner, Yeo, Nakashima and Gage2010; Skene et al., Reference Skene, Illingworth, Webb, Kerr, James, Turner, Andrews and Bird2010). In particular, two CpGs in the oxytocin receptor gene were found hypomethylated in OCD patients compared to controls (Park et al., Reference Park, Kim, Jeon, Kang and Kim2020). The lack of replication and validation in candidate epigenetic studies has led to conducting epigenome-wide studies without prior hypotheses about which genes might have epigenetic alterations in OCD patients. These studies would confirm that DNA methylation plays an important role in the etiology of OCD. About 2000 genes, previously identified as associated with OCD, were found differentially methylated in peripheral blood samples, including BCYRN1, BCOR, FGF13, ARX, and HLA-DRB1 (Yue et al., Reference Yue, Cheng, Liu, Tang, Lu, Zhang, Tang and Huang2016). Hypomethylation was also detected in brain tissues of cortical and ventral striatum in post-mortem analysis of individuals with OCD (de Oliveira et al., Reference de Oliveira, Camilo, Gastaldi, Sant’Anna Feltrin, Lisboa, de Jesus Rodrigues de Paula, Moretto, Lafer, Hoexter, Miguel, Maschietto, Akiyama, Grinberg, Leite, Suemoto, de Lucena Ferretti-Rebustini, Pasqualucci, Jacob-Filho and Brentani2021). The differentially methylated regions belonged to genes involved in G-protein signaling pathways, immune response, apoptosis and synapse biological processes. Another epigenome-wide study on a wide cohort of OCD patients identified 12 differentially methylated CpGs, which are close to or in genes associated with dopaminergic transmission in the striatum and insulin signaling sensitivity (Campos-Martin et al., Reference Campos-Martin, Bey, Elsner, Reuter, Klawohn, Philipsen, Kathmann, Wagner and Ramirez2023).

Interestingly, a recent study identified five differentially methylated sites mapping to the region of the microRNA12136 gene (MIR12136) (Schiele et al., Reference Schiele, Lipovsek, Schlosser, Soutschek, Schratt, Zaudig, Berberich, Köttgen and Domschke2022), thus indicating a potential role of miRNAs in OCD onset. MicroRNAs (miRNA), small regulatory RNA, participate, through a post-transcriptional control of gene expression, in almost every cellular process (Shyu et al., Reference Shyu, Wilkinson and van Hoof2008), including axon outgrowth, embryonic patterning, neural differentiation (Cao et al., Reference Cao, Li and Chan2016), adult synaptic plasticity, and cognition (Rajman & Schratt, Reference Rajman and Schratt2017). However, only few studies to date have assessed a possible association between alterations in the expression of circulating miRNAs and OCD. One research identified miR22-3p, miR24-3p, miR106b-5p, miR125b-5p, and miR155a-5p expression as significantly increased in the OCD subjects compared to controls, suggesting their involvement with DNA damage, oxidative stress, hypoxia, and inflammation (Kandemir et al., Reference Kandemir, Erdal, Selek, Izci Ay, Karababa, Bayazit, Tasdelen, Ekinci and Yilmaz2015). Another research (Yue et al., Reference Yue, Zhang, Wang, Hou, Chen, Cheng and Wen2020) identified two miRNA (miRNA-132 and miRNA-134), previously associated with CNS-related pathologies, with higher expression in the OCD group compared to the control group. In addition to miRNA analyses, Song and colleagues (Song et al., Reference Song, Liu, Wu, Zhang and Wang2018) generated whole-genome gene expression profiles of peripheral blood mononuclear cells from 30 patients with OCD and 30 paired controls using microarrays: 45 mRNA were down-regulated and 6 mRNA up-regulated. Enrichment analysis showed that these genes mainly belonged to the ribosomal pathways. Finally, two studies (Lisboa et al., Reference Lisboa, Oliveira, Tahira, Barbosa, Feltrin, Gouveia, Lima, Feio dos Santos, Martins, Puga, Moretto, De Bragança Pereira, Lafer, Leite, Ferretti-Rebustini, Farfel, Grinberg, Jacob-Filho, Miguel and Brentani2019; Piantadosi et al., Reference Piantadosi, McClain, Klei, Wang, Chamberlain, Springer, Lewis, Devlin and Ahmari2021) explored differentially expressed genes in human postmortem brain samples of OCD subjects comparing to controls using RNA sequencing.

Finally, very few studies explored the overall changes in epigenetic signatures across the genome over the life course (Simpkin et al., Reference Simpkin, Howe, Tilling, Gaunt, Lyttleton, McArdle, Ring, Horvath, Smith and Relton2017). Nissen and coworkers (Nissen et al., Reference Nissen, Hansen, Starnawska, Mattheisen, Børglum, Buttenschøn and Hollegaard2016) were the first to longitudinally analyze DNA methylation in blood spots in neonates later diagnosed with OCD and in the same adolescents at the time of OCD diagnosis compared with matched controls. The authors failed to find significant results, probably due to the candidate genes design. Another study (Goodman et al., Reference Goodman, Burton, Butcher, Siu, Lemire, Chater-Diehl, Turinsky, Brudno, Soreni, Rosenberg, Fitzgerald, Hanna, Anagnostou, Arnold, Crosbie, Schachar and Weksberg2020) investigated DNA methylation differences in the critical period of the first peak of OCD onset (7-13 years old), identifying specific differentially methylated CpG associated with OCD; however, the lack of a longitudinal design prevented hypotheses about the causal role of these identified epigenetic factors on OCD development.

Altogether, the few available studies (Table 1) hint at a key role of epigenetic changes in OCD onset. The next step should be to investigate the relation between different (bio-psycho-social) sources of developmental exposure, epigenetic changes, and childhood-onset OCD, specifically in relation to the various stages of this critical period of development.

Table 1. Epigenetic studies on obsessive-compulsive disorder

Note. OCD = Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder; HCs = Healthy Controls.

Childhood OCD and heterochrony: an evolutionary and developmental hypothesis

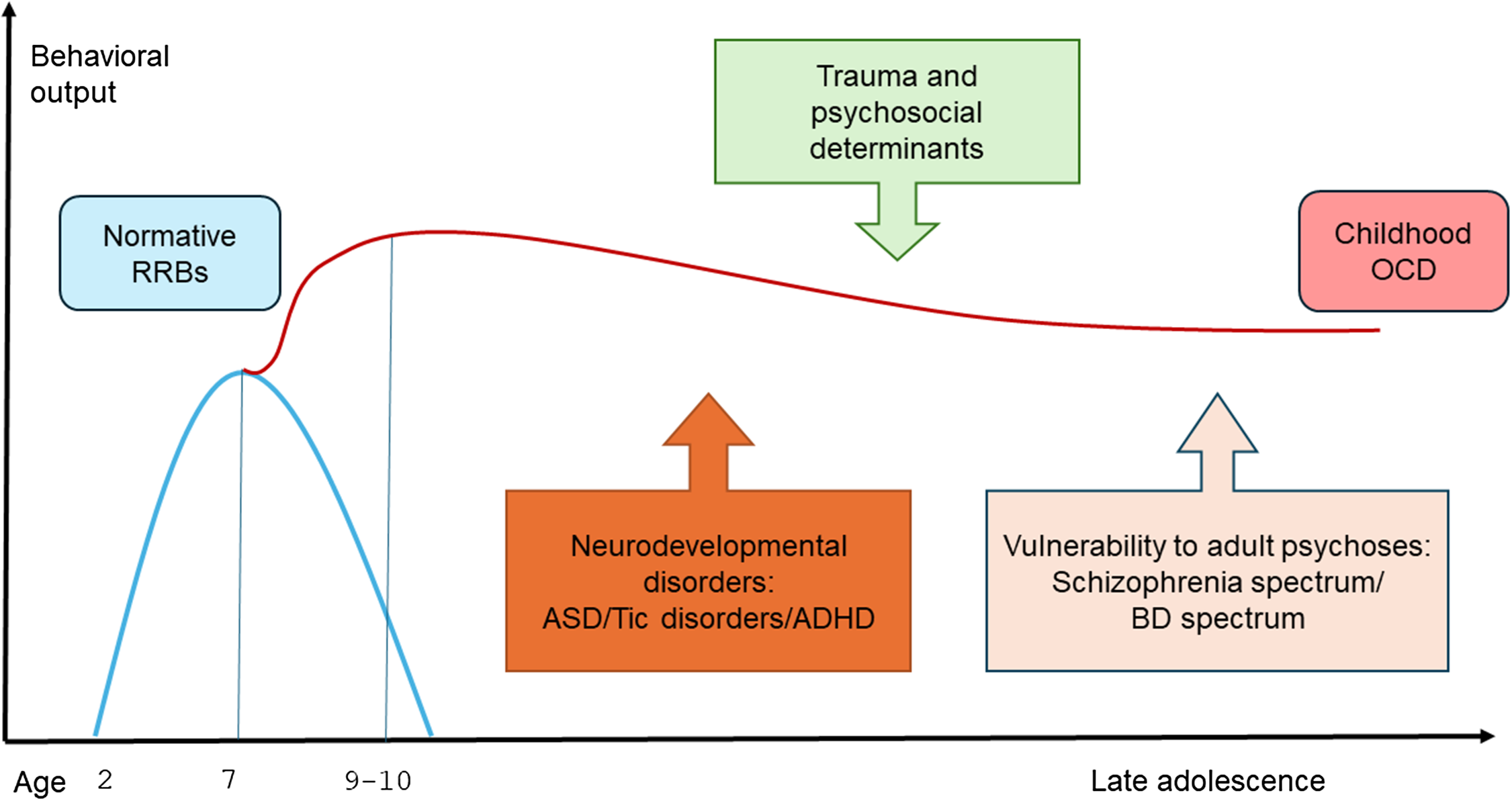

Altogether, childhood-onset OCD shows distinct comorbidity patterns (Geller et al., Reference Geller, Biederman, Faraone, Bellordre, Kim, Hagermoser, Cradock, Frazier and Coffey2001), which are age-at-onset dependent and reflect different developmental stages (Peris et al., Reference Peris, Rozenman, Bergman, Chang, O’Neill and Piacentini2017). In fact, OCS chronologically emerge as a continuation of RRBs, which are part of normative behavioral repertoire in typically developing children from 2 to 7 years of age. Their persistence after the age of 7, generally marked by maladaptive features, such as distress and emotional dysregulation, often covers divergent neurodevelopmental trajectories, whose phenotypical expressions extend from birth to late adolescence. Within this complex interplay, early trauma exposure may play a moderating role, interacting with the underlying developmental pathways. As such, OCD represents a crucial node for childhood psychopathology (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Temporal pattern and comorbidity profile of childhood OCD. Note: RRBs= restrictive and repetitive behaviors; OCD= obsessive-compulsive disorder; ASD=Autism spectrum disorders; ADHD= attention-deficit/Hyperactivity disorder; BD= bipolar disorder.

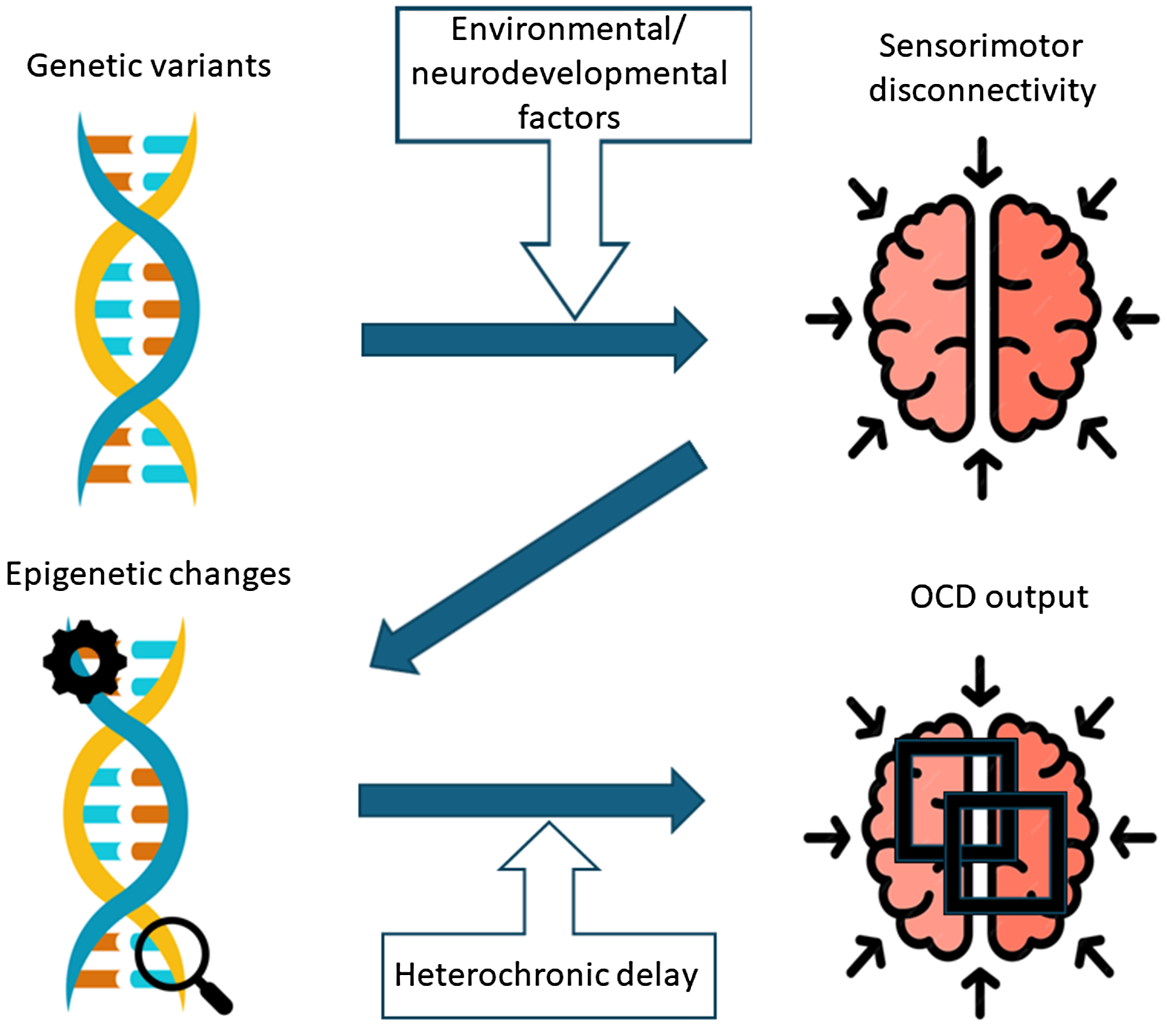

We hypothesize that this specific OCD temporal pattern is consistent with a model of developmental heterochronic shift in the timing and rates of evolutionarily conserved behavioral responses. Heterochrony refers to the evolutionary mechanism of genetically controlled diversification of the ontogenetic sequences of a trait, including behavioral traits (Wobber et al., Reference Wobber, Wrangham and Hare2010). Indeed, the retention of typical juvenile phenotypes in adults due to evolutionary changes in rates and timing of development (also referred to as “neoteny”) represents a core mechanism of recent human evolution (Brüne, Reference Brüne2000). Childhood OCD has been generally conceptualized in terms of dysfunctionality and deficit and, as such, investigated in its proximate (molecular-genetic, neurobiological, cognitive) mechanisms. Instead, under the lens of an evolutionary-developmental framework, OCD can be better explained as the result of developmental delays or non-completion of ontogenetically early behavioral patterns, eventually leading to mismatches with chronological age. In this vein, a heterochronic mechanism has already been advocated for RRBs in ASD (Crespi, Reference Crespi2013). We speculate that this model of developmental heterochrony may also account for the delay in attenuation of compulsive-like behaviors, synchronically or diachronically related to a wide range of neurodevelopmental perturbations, from childhood to adulthood.

Many of these neurodevelopmental disorders, regardless of the huge heterogeneity in symptoms and etiologies, are associated with a diffusely impaired multisensory/sensorimotor connectivity (Cascio, Reference Cascio2010). Indeed, in humans, multisensory integration networks are more vulnerable to early injury due to less constrained neural configurations and extensive neotenic synaptic plasticity, eventually leading to potentially relevant deviations in normative developmental trajectories (Stein & Rowland, Reference Stein and Rowland2011). Multisensory processing in fact, while tuned to species-specific spatiotemporal ranges (Borghi et al., Reference Borghi, Shaki and Fischer2022; Stevenson et al., Reference Stevenson, Ghose, Fister, Sarko, Altieri, Nidiffer, Kurela, Siemann, James and Wallace2014), retains highly plastic properties, especially in developmental years (Powers et al., Reference Powers, Hillock and Wallace2009; de Klerk et al., Reference de Klerk, Filippetti and Rigato2021). An early disruption in the maturation and refinement of sensorimotor grounding has an impact on the processing and integration of different sensory modalities into a coherent perceptual whole and on the execution of a contextually appropriate motor action (Carment et al., Reference Carment, Dupin, Guedj, Térémetz, Krebs, Cuenca, Maier, Amado and Lindberg2019), with a cascading effect on neurocognitive development (Dionne-Dostie et al., Reference Dionne-Dostie, Paquette, Lassonde and Gallagher2015). For example, individuals with ASD show specific sensory features (e.g., hypo/hyperactivity and unusual sensory interest), and a broad range of sensorimotor deficits (in visual-tactile perception, visual-motor skills, praxis and balance) (Schaaf et al., Reference Schaaf, Mailloux, Ridgway, Berruti, Dumont, Jones, Leiby, Sancimino, Yi and Molholm2023). Similarly, children with ADHD exhibit a unique pattern of trait-like impairments in multisensory integration, motor performance and coordination (McCracken et al., Reference McCracken, Murphy, Ambalavanar, Glazebrook and Yielder2022; Panagiotidi et al., Reference Panagiotidi, Overton and Stafford2017). In schizophrenia, there is evidence for a widened temporal window of integration (i.e., reduced ability to segregate stimuli in time) (Di Cosmo et al., Reference Di Cosmo, Costantini, Ambrosini, Salone, Martinotti, Corbo, Di Giannantonio and Ferri2021), as well as a reduced and less demarcated peripersonal space (i.e., the space surrounding the body for sensorimotor integration) (Ferroni et al., Reference Ferroni, Ardizzi, Ferri, Tesanovic, Langiulli, Tonna, Marchesi and Gallese2020; Ferroni et al., Reference Ferroni, Ardizzi, Magnani, Ferri, Langiulli, Rastelli, Lucarini, Giustozzi, Volpe, Marchesi, Tonna and Gallese2022), reflecting in specific motor and postural biomarkers (Carment et al., Reference Carment, Dupin, Guedj, Térémetz, Krebs, Cuenca, Maier, Amado and Lindberg2019; Presta et al., Reference Presta, Paraboschi, Marsella, Lucarini, Galli, Mirandola, Banchini, Marchesi, Galuppo, Vitale, Tonna and Gobbi2021; Walther & Strik, Reference Walther and Strik2012). Childhood adversities, including early traumatic experiences, also seem to alter the course of sensorimotor development, with a greater impact if the traumatic event occurs before the age of 7, which is a crucial period for the early maturation of sensory integration networks (Matson et al., Reference Matson, Barnes-Brown and Stonall2024).

Remarkably, compulsive-like behavior appears directly linked to multisensory impairment, regardless of the underlying neurodevelopmental disorder. For example, compulsive-like behaviors are strongly associated with distressing sensory experiences, such as sensory over-responsivity, both in children with ASD (Istvan et al., Reference Istvan, Nevill and Mazurek2020) and in children with OCD (Bart et al., Reference Bart, Bar-Shalita, Mansour and Dar2017; Dar et al., Reference Dar, Kahn and Carmeli2012). Therefore, we speculate that the heterochronic delay in attenuation of compulsive-like behavior would be driven by different sources of sensorial unbalance, due to heterogeneous (either biological or socio-psychological) developmental conditions. In this regard, the age of 7 would represent an important turning point, at which normative ritual behavior starts to decline in parallel with the maturation of sensorimotor networks or, conversely, pathologically persists as an expression of a failure of sensorimotor development (De Caluwé et al., Reference De Caluwé, Vergauwe, Decuyper, Bogaerts, Rettew and De Clercq2020).

In this respect, epigenetic changes might mediate the heterochronic mechanisms underlying the continuity of OCD phenotypes with typical childhood behavioral rituals (Figure 2). This is in line with the evidence that epigenetics and environmental exposures hugely affect developmental processes, leading to neurobiological dysfunctions with immediate or later consequences in life (Gupta et al., Reference Gupta, Kim, Artis, Molfese, Schumacher, Sweatt, Paylor and Lubin2010; Weaver et al., Reference Weaver, Cervoni, Champagne, D’Alessio, Sharma, Seckl, Dymov, Szyf and Meaney2004). The fact that the brain exhibits high plasticity and undergoes prolonged development over time has both advantages and disadvantages; on the one hand, it allows for a prolonged fine-tuning of sensorimotor grounding for higher cognitive and social functions throughout development. On the other, it exposes the high “flexibility” of synaptic networks to divergent developmental trajectories with consequently different behavioral outputs (Crespi & Dinsdale, Reference Crespi and Dinsdale2019; Tonna et al., Reference Tonna, Ottoni, Borrelli, Gambolò, Dell’Uva, Di Donna, Parmigiani and Marchesi2023). Therefore, epigenetic mechanisms might bridge the gap between the disrupted sensorimotor background and childhood OCD, specifically in relation to the various stages of this critical development period. In this respect, different epigenetic mechanisms, which play a key role in neural circuit development, maturation, and function, could be involved, with preliminary evidence for both transcriptional (DNA methylation), and post-transcriptional (miRNA) modifications of gene expression in OCD patients. Other epigenetic mechanisms, such as histone modifications and chromatin remodeling, could also be at work, due to their role in neurogenesis and synaptic plasticity and their association with various neurological and psychiatric disorders (Borrelli et al., Reference Borrelli, Nestler, Allis and Sassone-Corsi2008; Ma et al., Reference Ma, Marchetto, Guo, Ming, Gage and Song2010; Nelson & Monteggia, Reference Nelson and Monteggia2011; Telese et al., Reference Telese, Gamliel, Skowronska-Krawczyk, Garcia-Bassets and Rosenfeld2013; Zhang & Meaney, Reference Zhang and Meaney2010).

Figure 2. Developmental heterochronic model of childhood obsessive-compulsive disorder.

The ultimate causes of the delay in developmental attenuation of compulsive-like behavior have yet to be investigated. It is remarkable however, that across vertebrate phylogeny rituals and compulsive-like behaviors invariably conserve the adaptive significance of coping with conditions of environmental unpredictability (Eilam et al., Reference Eilam, Zor, Szechtman and Hermesh2006) or “high entropy” states (Hirsh et al., Reference Hirsh, Mar and Peterson2012). Across taxa in fact, whatever condition of potential danger or threat (Boyer & Liénard, Reference Boyer and Liénard2006; Szechtman & Woody, Reference Szechtman and Woody2004; Woody & Szechtman, Reference Woody and Szechtman2013), or anxiety-related uncertainty (Krátký et al., Reference Krátký, Lang, Shaver, Jerotijević and Xygalatas2016; Lang et al., Reference Lang, Krátký, Shaver, Jerotijević and Xygalatas2015) may trigger behavioral ritualization. Accordingly, the peculiar structural features of ritual behavior, based on acts repetition and intrusion of nonfunctional acts (Eilam, Reference Eilam2017) serve the function to interrupt the automaticity of motor performance as to align behavioral response to changing environments (Blanchard et al., Reference Blanchard, Blanchard, Rodgers, Olivier, Mos and Slangen1991; Schleyer et al., Reference Schleyer, Diegelmann, Michels, Saumweber, Gerber, Menzel and Benjamin2013; Stürzl et al., Reference Stürzl, Zeil, Boeddeker and Hemmi2016). In this connection, OCD compulsions and ritual behavior share overlapping features in terms of face validity (i.e., homologous motor structure) (Boyer & Liénard, Reference Boyer and Liénard2006; Lang et al., Reference Lang, Krátký, Shaver, Jerotijević and Xygalatas2015), construct validity (i.e., homologous neurobiological pathways, centered on basal ganglia structures) (Graybiel, Reference Graybiel2008) and predictive validity (as shown by robust animal models of OCD) (Wolmarans et al., Reference Wolmarans, Scheepers, Stein and Harvey2018). Such evolutionarily conserved proximate and ultimate mechanisms would therefore suggest a homologous continuity between ritual behavior and OCD compulsions (for a review, see: Tonna et al., Reference Tonna, Marchesi and Parmigiani2019; Tonna et al., Reference Tonna, Ponzi, Palanza, Marchesi and Parmigiani2020). During development, ritual behavior is gradually abandoned in favor of more adaptive cognitive-behavioral strategies along with sensorimotor maturation and the refinement of executive functions (De Caluwé et al., Reference De Caluwé, Vergauwe, Decuyper, Bogaerts, Rettew and De Clercq2020). We hypothesize however, that in case of impaired sensorimotor maturation, due to early deviations from normal developmental patterns, compulsive-like behavior, instead of being switched off, is maintained or reinforced with the adaptive function of coping with condition of sensory unpredictability.

This evolutionary perspective fits well with the evidence of the homeostatic function of children’s normative RRBs to cope with sensory and environmental unpredictability due to daily life contingencies (Evans & Maliken, Reference Evans and Maliken2011). RRBs in children with ASD have the same compensatory function of decreasing sensory arousal, simplifying complex situations and fostering a sense of control (Glenn et al., Reference Glenn, Cunningham and Nananidou2012). Interestingly, in both ASD and typically-developing children, compulsive-like behaviors are directly associated with conditions of sensory unbalance (Schulz & Stevenson, Reference Schulz and Stevenson2019). In individuals with OCD, the very motor structure of their compulsions is directly related to the underlying developmental perturbation, as it raises in complexity (in terms of acts repetition and ritual duration) in relation to increasing severity of both pre-psychotic symptoms (Tonna et al., Reference Tonna, Ottoni, Pellegrini, Mora, Gambolo, Di Donna, Parmigiani and Marchesi2022) and childhood trauma experiences (Tonna et al., Reference Tonna, Ottoni, Borrelli, Gambolò, Dell’Uva, Di Donna, Parmigiani and Marchesi2023). Therefore, we assume that fixed, evolutionarily conserved behavioral patterns may give order and control over different “high-entropy” or chaotic sensory states, due to sensorimotor networks, which in humans, because of their high plasticity, are also inherently vulnerable.

The effect of sensory balancing due to OCS would eventually lead to more stable syndromic configurations, allowing the individual to preserve specific functional domains in the real-life. Unfortunately, longitudinal studies on the effect of childhood OCD over the psychopathological course and the individual’s functioning in the real-life are lacking. However, a sort of OCD counterbalancing mechanism appears to be actively at work in comorbid OCD-schizophrenia adults. In those patients in fact, mild-moderate OCS are associated with more preserved levels of functioning (Tonna et al., Reference Tonna, Ottoni, Paglia, Ossola, De Panfilis and Marchesi2016b; Tonna et al., Reference Tonna, Ottoni, Paglia, Ossola, De Panfilis and Marchesi2016c), particularly in those functional areas (vocational and everyday activities), which are more sensitive to the superimposed “ordering” effect of ritual behavior (Tonna et al., Reference Tonna, Borrelli, Aguglia, Bucci, Carpiniello, Dell’Osso, Fagiolini, Meneguzzo, Monteleone, Pompili, Roncone, Rossi, Zeppegno, Marchesi and Maj2024).

Ultimately, we suggest some possible clinical and therapeutic implications of the evolutionary-developmental hypothesis of OCD compulsions proposed here, based on the heterochronic shift in the timing and rates of conserved behavioral responses.

1) Childhood OCD might represent a putative biomarker of underlying neurodevelopmental perturbation, due to both biological and psychosocial determinants.

2) Prominent compulsive-like symptoms may have a pathoplastic effect, as they can mask symptoms pertaining to other diagnostic entities, particularly if their clinical presentation is prodromal, sub-threshold or non-prototypical.

3) Childhood OCD might influence the course and outcome of underlying psychopathological trajectories, as its homeostatic role in regaining a sensory balance might sustain levels of functioning and perhaps prevent or at least mitigate the onset of full-blown symptoms.

Of course, this is not to say that childhood OCD necessarily stems from neurodevelopmental conditions or vulnerabilities. Early-onset OCD may be in fact direct expression of “pure” OCD dispositions and/or be released by any pathogenic mechanisms or injuries which eventually lead to fronto-striatal dysconnectivity (Graybiel, Reference Graybiel2008; Mataix-Cols et al., Reference Mataix-Cols, Wooderson, Lawrence, Brammer, Speckens and Phillips2004). Therefore, compulsive symptoms in childhood may actually identify subgroups of patients with different etiopathogenetic pathways.

The present contribution should be considered with the caveat of the following limitations. First, as a main limitation, this work is not a comprehensive review of all available evidence for an evolutionary and developmental approach to childhood OCD, but it cites selected papers that the authors considered as conducive to address the main hypothesis presented. Second, the hypothesis proposed does not fully capture the complexity of the intertwined neurodevelopmental pathways to childhood OCD; for example, it does not take into account other pathophysiological trajectories, such as intellectual disabilities, autoimmune conditions (e.g., Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal Infections-PANDAS-) or other organic forms of OCD (including rare genetic syndromes) (Runge et al., Reference Runge, Reisert, Feige, Nickel, Urbach, Venhoff, Tzschach, Schiele, Hannibal, Prüss, Domschke, Tebartz van Elst and Endres2023). Third, for the reason of brevity, an exhaustive description of OCD psychopathological profile was limited. This has left out important clinical facets of OCD, such as levels of insight and specific symptom dimensions, to name but a few, which might vary in accordance with the underlying neurodevelopmental background. Fourth, response to treatment has not been investigated. Future research should be addressed to identify specific treatment targets based on different phenotypic subtypes, underlying comorbidities and developmental stages.

In conclusion, the approach of this study is speculative but provides hypotheses to be tested in future research. In particular, our hypothesis of developmental heterochrony allows to grasp the continuity of OCD phenotypes with typical childhood behavioral repertoire and thus to highlight the adaptive significance of ritual behavior across phylogeny. This continuity is rooted in development trajectories, which are highly inherently malleable (Hauser et al., Reference Hauser, Will, Dubois and Dolan2019). We suggest that the chronological shift of compulsive-like behaviors, which are normative preprogramed behaviors at specific temporal stages, may be driven by any condition of multisensory unbalance due to neurodevelopmental factors in association with child’s environment (e.g., early life stress and childhood adverse experiences) through epigenetic mechanisms, with a profound impact on connectivity organization and brain maturation.

Analyzing the timing and type of childhood adversities and/or neurodevelopmental perturbations in association with OCD onset and epigenetic changes could reveal new findings. In this regard, cohort studies based on exhaustive biopsychosocial data would be needed to test the main hypothesis of the study. Furthermore, subgrouping youth OCD population based on their comorbidities and comparing them on the phenotypic expressions of OCS might provide a deeper insight into the clinical heterogeneity of the disorder and refine diagnostic tools. Since OCD is a multifactorial condition, it should be further explored how gene-environment interactions influence epigenetic processes. In particular, longitudinal studies based on high-throughput sequencing technologies would allow understand how epigenetic factors can mediate lived experiences and thus contribute to the persistence of OCS after childhood. This might form the basis for new guidelines aimed at prompt therapeutic interventions, including epi-drugs or epigenetic editing.

Acknowledgements

None.

Authors’ contribution

MT designed the study, which was critically revised by all the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.