Policy Significance Statement

This article develops a framework for governing digital identity (eID) systems that complements existing regulatory and risk management methods. This article’s proposed framework provides a set of principles and recommendations that can be incorporated into policy and practice while deploying or governing eID systems. It highlights the need for contextual flexibility and stakeholder participation to enable a more responsible development of eID systems.

1. Introduction

Digital identity (eID) is rapidly becoming the dominant form of identification for individuals when interacting with businesses, governments, or aid agencies. It is an essential component of the global digital infrastructure, which has an estimated 4.4 billion internet users, 5.1 billion mobile users, and a global e-commerce spend of $3.5 trillion (Kemp, Reference Kemp2019; Young, Reference Young2019). Social media technologies have become quintessential for communication and economic activity, driving billions of daily transactions (Clement, Reference Clement2019, Reference Clement2020; Iqbal, Reference Iqbal2020). Small and medium sized businesses rely heavily on digital services and eID infrastructure to deliver products and services. Companies such as 23andMe and DnaNudge combine DNA and eID data to build personalized services. Official identity documentation is crucial for accessing socioeconomic opportunities, and currently an estimated 1.1 billion people lack access such an artifact (Gelb and Metz, Reference Gelb and Metz2018; World Bank, 2018). Governments have responded to this challenge by ramping up eID programmes as a means for providing official identification and replacing legacy, offline systems. This has meant access to financial aid and welfare is increasingly being linked to identification systems, such as Aadhaar and UN PRIMES—linking logics of universal access to digital access which in turn has led to exclusion from social protection for marginalized populations (Masiero, Reference Masiero2020). Global COVID-19 response strategies have also created a vast variety of technological solutions and techno-commercial arrangements underpinned by eID systems (Daly, Reference Daly2020; Edwards, Reference Edwards2020; Masiero, Reference Masiero2020; Yeung, Reference Yeung2020).

eID systems can extract ever-increasing amounts of personal data, that can lead to a loss of privacy and agency as these systems get linked to services and analytics platforms that then track, exclude or penalize noncompliant behavior such as using welfare money to purchase alcohol or gambling products (Arora, Reference Arora2016; Tilley, Reference Tilley2020). While eID systems demand greater transparency from the individual, owners of these systems are perceived as being opaque in their data management and decision-making practices (Hicks, Reference Hicks2020; Schoemaker et al., Reference Schoemaker, Baslan, Pon and Dell2021). The certainty of eID provisioning limits the ability for vulnerable populations to negotiate their status with respect to the government and the care social service workers can provide on their behalf (Arora, Reference Arora2016; Schoemaker et al., Reference Schoemaker, Baslan, Pon and Dell2021). In the global south, governments are not just regulators of the ID data but also distribute it for private sector exploitation (Hicks, Reference Hicks2020). These regions may lag in the development of data protection and data privacy regulation or lack the capacity to implement and monitor regulation effectively.

In this article, we consider a range of responses to the challenges of governing eID systems. First, we describe the current approaches to eID governance and discuss some of their key deficiencies, such as gaps in existing regulations and regulatory oversight bodies, the lack of incentives for organizations to implement effective data management processes, and the limitations of using siloed technological solutions to address a networked ecosystem problem. We propose that some of these deficiencies can be addressed if principles of responsible innovation (RI)—rooted in user or data subject trust—are more actively employed when considering current and future governance models for eID systems. We then outline how an RI framework for eID systems governance might look like, highlighting that RI principles embed deliberate practices to manage and direct emerging innovations toward societally beneficial outcomes. The proposed framework seeks to bring deliberation and democratic engagement to the fore when considering how to develop, monitor, and govern eID systems. Through this article, we seek to build on nascent research in eID system governance and appeal for greater interdisciplinarity in researching and governing eID systems. The proposed framework is based on extensive review of RI literature and emergent eID systems literature and use cases. eID systems literature and examples have been used to substantiate the principles-based approach RI proposes.

The proposed framework is modular and nonprescriptive but can be used as an assessment tool for individuals and organizations designing, developing, managing, governing, or regulating eID systems. The proposed framework supports existing and future governance models for eID systems, based not only on the RI principles but also the literature we have reviewed that investigates concerns and potential solutions for governing eID systems in a more responsible manner. Through a user-centric, deliberative, and inclusive approach, the RI approach aims to address issues of trust and contextual engagement often lacking in eID systems. The proposed framework in this article is complimentary to scholarship on data justice and the realization of societal and human rights mediated through digital systems.

2. eID Creation Methods

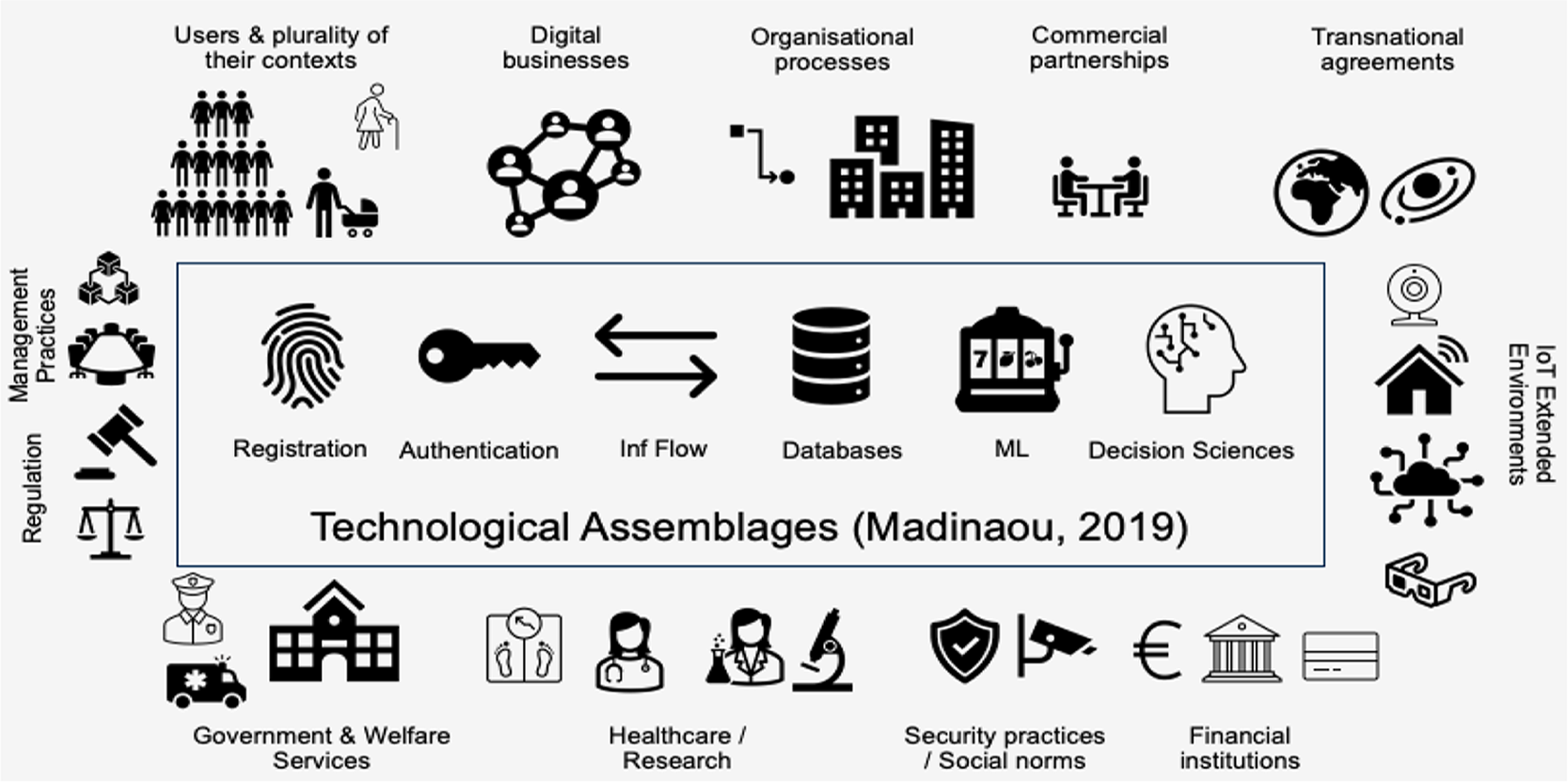

eID tends to be studied within silos that focus either on digital persona and identity management strategies (Boyd, Reference Boyd2011; Trottier, Reference Trottier2014; Feher, Reference Feher2019), on the various underpinning ID technology types (Dunphy and Fabien, Reference Dunphy and Fabien2018; Takemiya and Vanieiev, Reference Takemiya and Vanieiev2018; Toth and Anderson-Priddy, Reference Toth and Anderson-Priddy2018), the potential use of eID for socioeconomic gain (Gelb and Metz, Reference Gelb and Metz2018; White et al., Reference White, Madgavkar, Manyika, Mahajan, Bughin, McCarthy and Sperling2019), or the associated risks from these sociotechnical systems (Baker and Rahman, Reference Baker and Rahman2020). Madianou (Reference Madianou2019) suggests viewing identification components (such as biometrics, IT infrastructure, blockchain, and AI) as technological assemblages since the convergence of these components amplifies the risks associated with digital identification. We look at digital ID systems as a whole, not just technological assemblages, but also organizational processes and commercial arrangements that enable digital identification with or without an individual’s awareness, and include the stakeholders involved in its development, deployment, management, and usage.

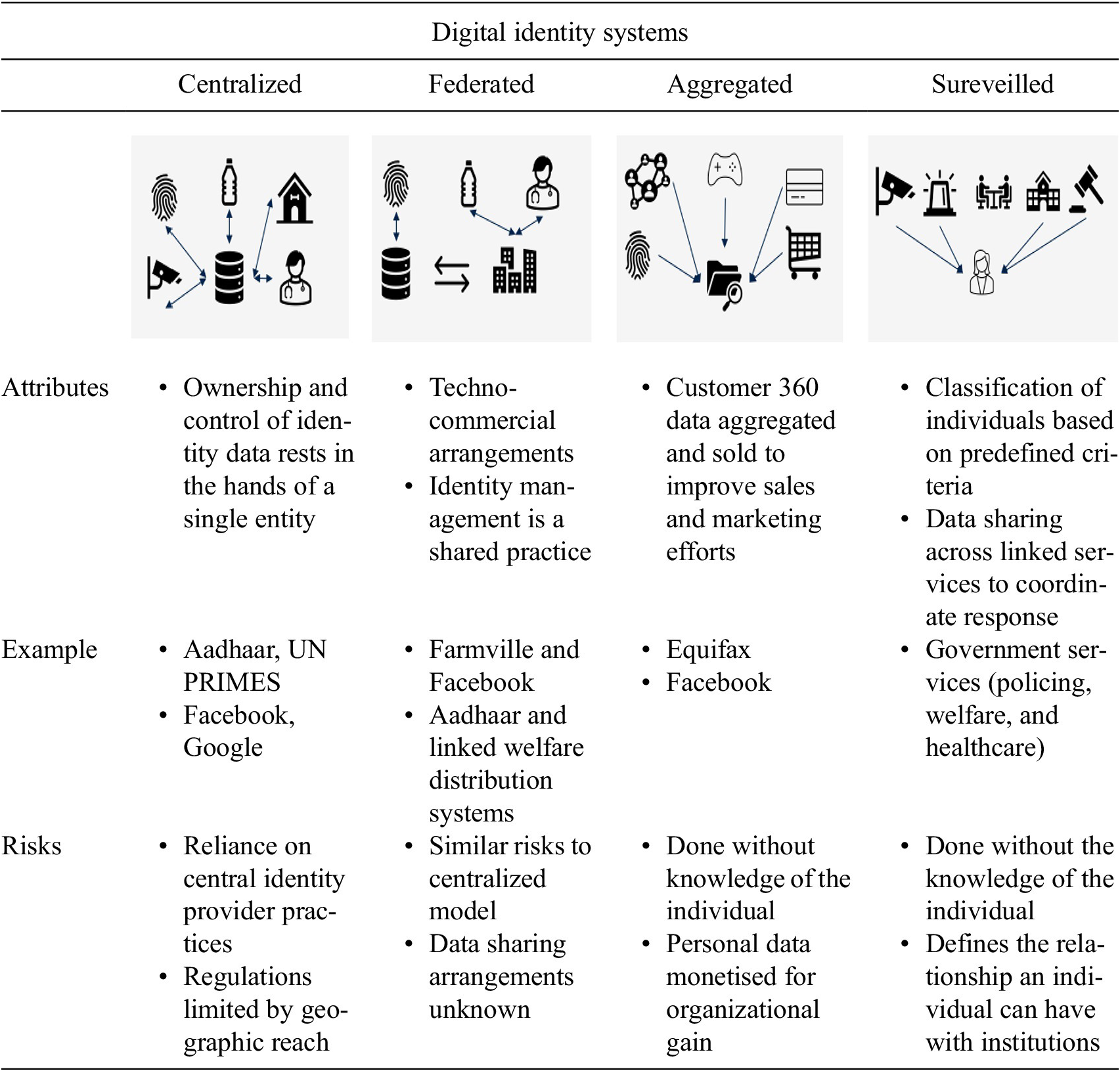

Centralized eID infrastructures such as UN PRIMES and Aadhaar, India’s national ID programme, are managed by large organizations. Transnational platforms, such as Google and Facebook, are private sector examples of centralized eID infrastructures. An individual user must provide identification and authentication evidence as mandated by the central ID provider and relinquishes control of how their personal data is stored, used, and analyzed when they sign up to use the services that overlay the ID system. There is vast variance in data protection laws’ prevalence, content, and implementation of procedural security requirements on centralized eID providers.

As digital business models have proliferated, federated identification, where digital businesses delegate authentication processes to existing identity providers, has become a commonly used authentication and transacting method. These partnerships represent techno-commercial arrangements where an individual’s data is shared between organizations. By consenting to use federated ID verification, an individual user signs off on a data sharing agreement between the digital business and the identity provider. The extent of data shared has limited to no input from the individual beyond initial consent. Ownership, security, and control of the individual’s identity data becomes a shared exercise between the digital business and identity provider.

Data aggregator business models are another method of digital identification, where digital interactions of an individual across platforms and services are aggregated to create a 360° snapshot of that individual. This aggregated data is then sold to businesses to enhance sales and marketing efforts by analyzing customer trends and behaviors. The individual has little to no knowledge of what data has been aggregated and sold unless systems are breached.

Surveillance practices can also create digital identities. Preemptive policing techniques can categorize groups into capricious classifications like “criminal,” “annoying,” and “nuisance” (Niculescu-Dinca et al., Reference Niculescu-Dinca, van der Ploeg and Swierstra2016). Not only do the groups in question not know what identities have been created of them, these classifications are difficult to change once documented. Ambiguous data sharing arrangements between government departments can cause “at risk” individuals, (e.g., refugees) to be seen “as risks,” which can justify greater surveillance (Fors-Owczynik and Valkenburg, Reference Fors-Owczynik and Valkenburg2016; Niculescu-Dinca et al., Reference Niculescu-Dinca, van der Ploeg and Swierstra2016). Surveillance categorisations from one public arena form identities for individuals across social institutions and can affect their access and outcomes to opportunities (Tilley, Reference Tilley2020).

Self-sovereign identity (SSI) provides an alternate paradigm for identification where the individual creates and controls their digital credentials. SSI relies on a decentralized identification framework, personal data storage lockers and (often) blockchain technologies (Lyons et al., Reference Lyons, Courcelas and Timsit2019). However, its usage is still nascent and thus out of scope for this article.

As highlighted above, eID methods are a mix of technological, commercial, and organizational arrangements. Even where the individual initiates the creation of their eID, the processes for identity management are controlled and managed by organizations that have divergent socioeconomic imperatives (Table 1).

Table 1. Digital identity creation methods

3. Current Approaches to eID Governance

The current methods for governing eID systems have focussed on addressing known risks associated with these systems primarily through regulatory frameworks, organizational governance and risk management approaches, and technological solutions.

3.1. Regulatory frameworks

Regulations that govern personal data usage online fall under the categories of privacy laws, data protection laws, consumer law, and competition law. By 2018, 161 countries had embarked on national identification programmes that were reliant on digital technologies; 132 jurisdictions had instituted data privacy laws, and an estimated 28 more countries had plans to enact data protection laws (World Bank, 2018; Greenleaf, Reference Greenleaf2019). Data protection and data privacy laws aim to ensure an individual’s control over their digital footprint.

However, laws are only as effective as their implementation. In the global south, regulations focussed on digital rights are still in their nascency, while large scale eID programmes have already been deployed to subsume significant proportions of the population (Hicks, Reference Hicks2020). In India, while a draft data protection bill was still being discussed in Parliament, enrolment in Aadhaar has surpassed 90% of the population (Pandey, Reference Pandey2017; Tomlinson, Reference Tomlinson2017). In the USA, privacy in the digital realm is diffused across a variety of federal, state, tort laws, rules and treaties, and digital businesses can only be taken to court on infringements of their own, often vague, privacy policies (Esteve, Reference Esteve2017). Legacy legal frameworks have limited adaptability to new technological developments and associated risks (Brass and Sowell, Reference Brass and Sowell2020). Moreover, a focus on data protection laws alone ignores the constant evolution of data mining methods, which can easily reidentify aggregated and anonymized personal data (Gandy, Reference Gandy2011).

While regulations, such as GDPR, provide protection for individuals, the responsibility to actively monitor personal data trails still lies with the data subject, who may be unaware of their exposure to data processing risks, and unaware of their digital rights or how to exercise them. Organizations controlling data create significant procedural hindrances for individuals to access or delete their own data (Turner et al., Reference Turner, Quintero, Turner, Lis and Tanczer2020; Myrstad and Kaldestad, Reference Myrstad and Kaldestad2021). Owing to territoriality, victims of data protection violations, such as revenge porn, fail to get harmful content removed if hosted on servers in jurisdictions that are not signatories to data protection agreements (Cater, Reference Cater2021).

The digital marketplace is heavily impacted by platform economics, where a single player can dominate the market. While a dominant market position in itself is not anticompetitive, the abuse of a dominant position is uncompetitive. In digital markets, a dominant player can abuse its position through the accumulation of large amounts of personal data or with the use of concealed data processing practices (Khan, Reference Khan2019). This creates objective costs for its customers in terms of risks of identity theft, inadvertent disclosure of personal data, and risks of manipulation and exclusion. Concealed data practices can undermine competition objectives by allowing privacy degrading technologies to persist unbeknown to its users, as seen with examples such as Apple promoting Apple music while subverting Spotify or Google search biases that rank Google products and services higher than alternatives (Zingales, Reference Zingales2017; Khan, Reference Khan2019; Witting, Reference Witting2019; Kemp, Reference Kemp2020). Additionally, through the extraction and analysis of vast amounts of personal data and ever more tailored services to its user base, dominant players can create significant barriers to entry for any privacy enhancing alternatives (EDRi, 2020).

An economic lens alone does not capture the trade-offs between privacy and access to free services, such as search and social networks, and anticompetitive practices (Kerber, Reference Kerber2016; Kemp, Reference Kemp2020). Recent examples have exposed the ineffectiveness of competition laws in dealing with large platforms, as they are willing to pay significant fines for violations but not to change their business practices (EU Commission, 2017, 2018, 2019; Amaro, Reference Amaro2019; Riley, Reference Riley2019). Greater coordination among data protection, competition and consumer protection authorities is required when considering digital law infringements.

Digital identities are also constructed and complemented with a growing body of data from our extended environments, through IoT enabled devices we use, wear on our bodies and install in our personal and ambient spaces. The proliferation of these devices will create new threats and unexpected harms, but can create new data markets that can be monetised (Tanczer et al., Reference Tanczer, Steenmans, Brass and Carr2018). Regulation alone cannot address the dynamism inherent in the digital space, nor can it be expected to be comprehensive or proportionate in its nascency. An alignment on a broader set of instruments, such as (use case specific) regulation through technology, innovation sandboxes, or technical and normative standards is needed (Ringe and Ruof, Reference Ringe and Ruof2018; Engin and Treleaven, Reference Engin and Treleaven2019). Engin and Treleaven (Reference Engin and Treleaven2019) cite examples such as Civic Lab in Chicago, Citizinvestor and CitySourced as new models for improving citizen state participation through technology and informing changes in policy at local and regional levels.

3.2. Organizational governance and risk management approaches

Individuals perceive themselves to be lacking power in managing their privacy when interacting with digital systems providers and expect these organizations to be responsible in their privacy practices. This expectation, of responsible and ethical practices, can extend beyond current legal boundaries and into moral norms of information use (Bandara et al., Reference Bandara, Fernando and Akter2020). Organizations must hence develop robust governance and risk management processes not only to ensure regulatory compliance but also to foster a safe environment for individuals to participate in their service offerings.

In order to comply with the GDPR and emerging national data protection requirements, there has been an increase in investment in the privacy and data protection function within organizations. Over 70% of organizations surveyed saw an increase in data protection and privacy staff and 87% had appointed a data protection officer (Deloitte, 2018). However, privacy policies, data usage, and consent notices are often written in inaccessible language and formats that can lead to behavioral decision-making problems (such as framing effects and status quo bias), which cast doubts on whether true consent is actually being provided (Kerber, Reference Kerber2016). Additionally, consent is only one of many bases for lawful data processing, others may include commercial contractual reasons, the legitimate interests of data controllers or third parties (Art. 6 GDPR, 2016), or if proven necessary to perform a task for public interest (Art. 6 GDPR, 2016), such as aid, welfare distribution and national security. These alternate data processing methods may be used more often than consent methods and done without data subjects’ knowledge.

The humanitarian sector, a 150-billion-dollar industry, has increasingly been required to show greater accountability to donors and traceability of funds. Digital infrastructures, such as biometric registration, provide an appearance of exactness that is deployed to address these demands, often in instances where it is not required (Madianou, Reference Madianou2019). While demanding greater transparency from vulnerable populations, developmental organizations running eID systems can seem opaque in their data governance practices and subsequent decision-making based on personal data collected (Schoemaker et al., Reference Schoemaker, Baslan, Pon and Dell2021). “Standard practices” do not consider contextual and cultural concerns on the ground. Refugees and aid beneficiaries have limited avenues to cite their concerns or negotiate how they had like their identities to be recorded (Baker and Rahman, Reference Baker and Rahman2020; Schoemaker et al., Reference Schoemaker, Baslan, Pon and Dell2021). Remote location of ID registration centers may require vulnerable populations spend resources they do not have or bring up security concerns (Baker and Rahman, Reference Baker and Rahman2020). Errors in these infrastructures (such as lack of matches found or connectivity issues) are cited in percentages while ignoring the impact that errors can have on vulnerable populations (Drèze et al., Reference Drèze, Khalid, Khera and Somanchi2017; Madianou, Reference Madianou2019). Most significantly, the digital infrastructures deployed may not address targeted inefficiencies. Aadhaar was aimed at addressing fraud in benefits distribution by ensuring traceability of food supply to the beneficiary. However, analysis suggests that fraud still exists with a majority of value leakage happening upstream (Drèze et al., Reference Drèze, Khalid, Khera and Somanchi2017; Khera, Reference Khera2019).

Corporations have limited incentives to address privacy and data security risks that lie outside organizational boundaries or are inherent in the digital value chain. Data aggregator business models are built on piecing together siloed information on individuals to mine or further sell onward. The onus of risk management across the entire ecosystem rests on the individual, who lacks information, resources, and technical know-how to assess and address her risk susceptibility.

Some suggested methods of addressing ethically complex questions associated with digital business practices include invoking fiduciary responsibilities on platforms, mandating algorithmic transparency and developing public sector owned ID banks (Pasquale, Reference Pasquale2015; Balkin, Reference Balkin2016; Dobkin, Reference Dobkin2017; Schwarz, Reference Schwarz2017). While relevant, these proposals primarily focus on large global entities while the use of eID technologies requires interventions at micro, meso, and macro levels and contextual analysis of each use case. If applied to Aadhaar such interventions could entail the formalization of a data protection law prior to deployment, civil society representation on the governing board of Aadhaar, transparency and formal notice on partnership arrangements with private sector suppliers and government departments, an independent auditor or Aadhaar operations and a clear means for addressing exclusions at every point of Aadhaar authentication (Anand, Reference Anand2021).

3.3. Technological solutions

Technological solutionism has become prevalent with the proliferation of low cost technological assemblages and the increased involvement of private sector companies in addressing complex sociopolitical problems (Madianou, Reference Madianou2019). This has led to the expansion of identity-based technological infrastructures in public sector and development settings, at times even before the deployment of policies and laws to govern their usage.

Technological solutions for enhancing user privacy and security are used to mitigate risks associated with data leakage or identity theft such as using distributed ledger based systems, proactive vulnerability screening technologies and using a network of professionals to monitor and respond to security threats (Dunphy and Fabien, Reference Dunphy and Fabien2018; Malomo et al., Reference Malomo, Rawat and Garuba2020). Depending on the risk scenarios anticipated, a vast variety of technologies are deployed (Heurix et al., Reference Heurix, Zimmermann, Neubauer and Fenz2015; The Royal Society, 2019).These solutions, while extremely relevant, often rely on the knowledge of a small group of experts, while alienating end users from understanding the risks posed to them. These technologies can in turn create unintended risks that are significantly harder to remediate. Blockchain technologies, for example, run the risk of codifying inaccurate identity information permanently if inaccurately entered at source. Yet, the suggested adoption of new technology to solve complex sociotechnical problems can receive more publicity and funding than using low-tech solutions (Madianou, Reference Madianou2019). Digital platforms use methods such as customer feedback aggregation or the deployment of blockchain solutions to mediate trust in their business. However, the same platforms may not take any responsibility for a breach of trust in interactions (Bodó, Reference Bodó2020). Each failed transaction, however, then reduces user trust in the system.

Principles of privacy by design are seen as gold standard practices to achieve in addressing digital risks, and its inclusion in GDPR has pushed organizations to develop more robust and proactive privacy practices, when dealing with an EU user base (Cavoukian, Reference Cavoukian2006; ICO, 2020). However, these guidelines have fallen short of clear specification and enforcement for lack of an internationally approved standard, and so provide limited incentive for technology companies to change their internal systems development methodologies or new product development processes. Additionally, by only focussing on privacy risks we implicitly accept technological solutionism as a path forward without understanding an issue within its complex environment (Keyes, Reference Keyes2020).

3.4. Limitations of current approaches

Current approaches to governance have often left the individual out of the decision-making process on the development, deployment, and usage of eID systems. Individuals as users, consumers, refugees, welfare participants, and digital citizens have to adopt predefined processes of identification and verification to avoid missing out on crucial socioeconomic benefits or opt-out entirely. In addition, these governance mechanisms are very rarely aligned, are deployed, and assessed separately, without a comprehensive understanding of the full normative, legal, technological, and commercial governance ecosystem needed to respond to the challenges posed by eID system.

In existing eID systems, individuals are compelled to transact with organizations whose internal data processing practices are often unclear or unknown. Trust is not just an engineering problem to solve and has “distinct cognitive, emotional, and behavioral dimensions which are merged into a unitary social experience” (Corbett and Le Dantec, Reference Corbett and Le Dantec2018; Kaurin, Reference Kaurin2020). Trust is built on reputation and mediated interactions between an individual and an organization. Reputation is the perceived competency of an organization in delivering a service and is based on past actions which provide a perception of what the organization stands for today (Briggs and Thomas, Reference Briggs and Thomas2015). Mediated interactions refer to a holistic experience of engagement, participation, and responsiveness between an individual and an organization over the lifecycle of their exchange (Corbett and Le Dantec, Reference Corbett and Le Dantec2018). In addition to interpersonal relations, trust in institutions has been based on transparency in procedures, systems of accountability, internal rules, norms, and governance mechanisms that establish trustworthiness for outsiders (Bodó, Reference Bodó2020). Digital technologies and processes, such as eID systems, impact trust as they bring new and unknown forms of risk to interpersonal and institutional relationships, and are often governed by procedures that sit outside known and familiar legal, political, economic, social, and cultural practices (Livingstone, Reference Livingstone2018; Bodó, Reference Bodó2020).

Opaque data processing practices diminish trust in organizations. Developing trust requires a two-way information flow to ensure individuals and organizations understand each others requirements and limitations. Interventions and artifacts built through stakeholder participation, such as security enhancing labeling practices, provide an avenue to enhance trust in digital technology ecosystems (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Blythe, Manning and Gabriel2020). Greater stakeholder participation in the development and deployment of eID systems, can help build trust in the digital ecosystem, address contextually relevant ethical concerns, ensure safety and security of individuals as well as achieve collective socioeconomic benefits.

4. Responsible Innovation

eID systems bring together stakeholders with divergent incentives and interests and become crucial vehicles in the applicability of rights and resources. Numerous studies have highlighted the need to balance divergent societal and economic interests and brought to the fore novel ideas of data justice and human rights recognition in digital systems (Mansell, Reference Mansell2004; Mihr, Reference Mihr2017; Taylor, Reference Taylor2017; Masiero and Bailur, Reference Masiero and Bailur2021; Niklas and Dencik, Reference Niklas and Dencik2021). Through the application of the RI framework, this study compliments the scholarship on digital social justice by providing pathways for greater stakeholder engagement that help contextualize digital systems within the environments they are intended to operate in and a means to bring forth value tensions that arise from the deployment of these systems.

Stahl et al. (Reference Stahl, Eden and Jirotka2013) define RI as “taking care of the future through collective stewardship of science and innovation in the present.” RI aims to move away from risk containment methods toward active steering of innovations through uncertainty. There are four principles to RI: anticipation, reflexivity, inclusion, and responsiveness with a focus on embedding deliberation and democratization in the innovation process (Owen et al., Reference Owen, Stilgoe, Macnaughten, Gorman, Fisher and Guston2013; Stilgoe, Reference Stilgoe2013; Stilgoe et al., Reference Stilgoe, Owen and Macnaghten2013). These principles highlight that science and technology and society are mutually responsive to each other, and RI provides methods to steer activities, incentives, investments, prioritization toward a shared purpose (Owen et al., Reference Owen, Stilgoe, Macnaughten, Gorman, Fisher and Guston2013).

RI principles have been applied across several domains, directing research and innovation toward socially desirable outcomes. Public dialog on the use of nanotechnology in healthcare helped steer research direction and associated funding into areas that support social values (Jones, Reference Jones2008; Stilgoe et al., Reference Stilgoe, Owen and Macnaghten2013). The STIR program (Socio-Technical Integration Research) aims to embed ethical deliberation early in the innovation process in order to reduce risks downstream (Fisher and Rip, Reference Fisher and Rip2013). In ICT, RI faces a multitude of challenges: most development and innovation work is done by the private sector, but responsibility of socially pertinent outcomes gets shared across multiple organizations including the public sector. While the ICT field has a plethora of professional bodies, each with their own ethical guidelines, the voluntary nature of these organizations limits the effectiveness and reach of proposed standards and guidelines (Stahl et al., Reference Stahl, Eden and Jirotka2013). Not only does ethical noncompliance have no repercussions in ICT, there is also a lack of educational preparedness in ethical issues for aspiring professionals (Thornley et al., Reference Thornley, Murnane, McLoughlin, Carcary, Doherty and Veling2018).

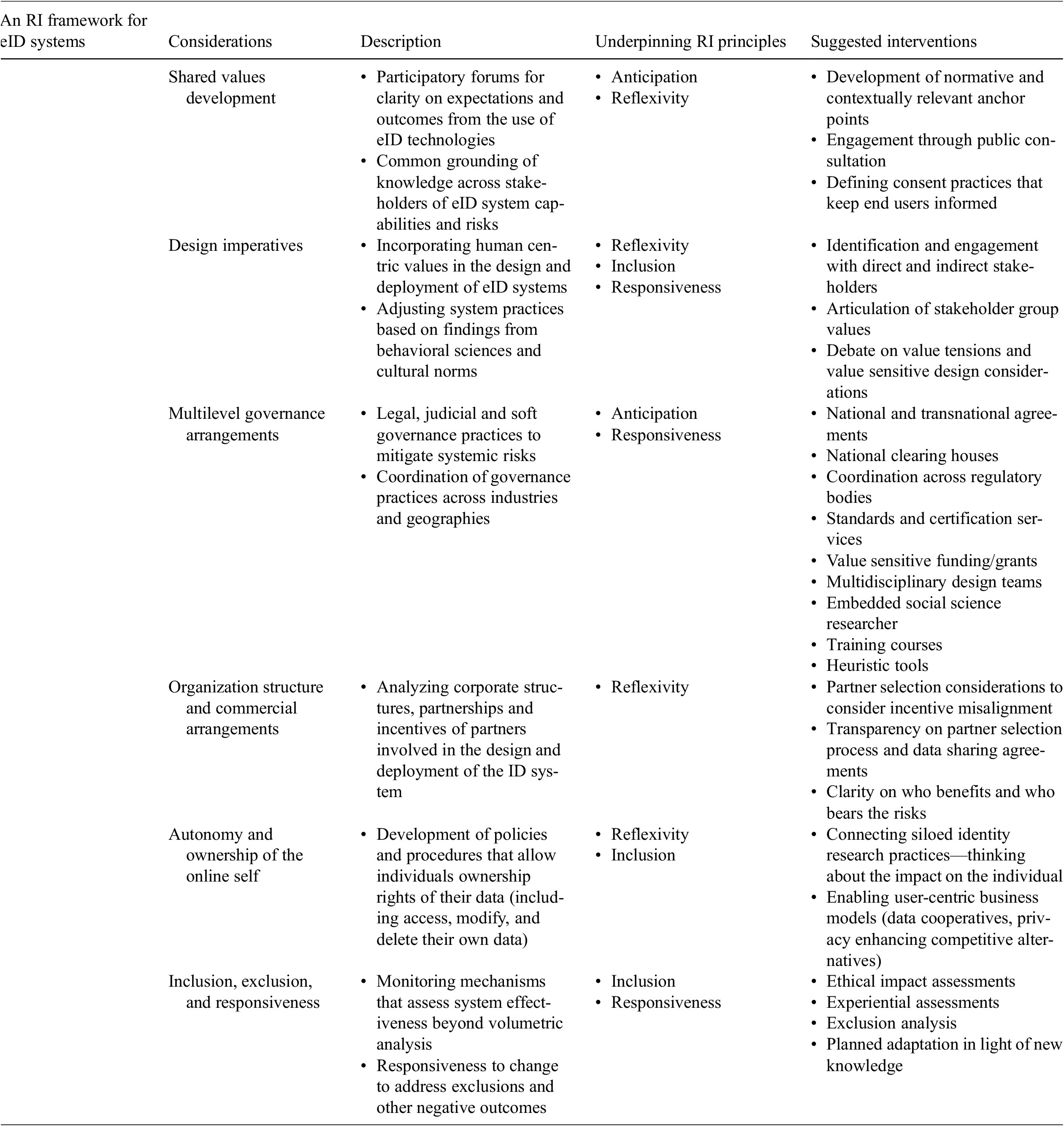

As we have highlighted, eID systems represent technological, organizational, and commercial arrangements that connect an individual to a variety of socioeconomic environments. With the current pace of digital innovation, we can expect that eID systems will continue to proliferate across geographies, sectors, and services. Supporting this growth requires greater stakeholder participation and clarity on how the risks and benefits can be managed and distributed effectively across society. As we have seen in Section 3, current governance approaches alone do not provide effective mechanisms for addressing the risk–reward trade-off and leave the individual out of the innovation process. RI provides a supporting framework to govern the eID ecosystem that can foster trust and bring user considerations to the forefront of debate. We use the four principles of RI to develop a framework to govern eID systems (Table 2). The framework focusses on six broad areas for the governance of eID systems. It aims to embed democratization and deliberation in the development, use, and management of eID ecosystems.

Table 2. Responsible innovation for eID systems

5. RI for eID Systems

RI provides a framework to develop eID systems in socially desirable ways. Our analysis is focussed on the entire system (see Figure 1), including all participants (developers, users, ID providers, digital businesses, public sector organizations, and regulators) and all forms of eID management (technical, organizational, sociotechnical, commercial, and surveillance). By addressing the system as a whole, we acknowledge the complex sociotechnical interactions underpinning eID systems and aim to build an environment to achieve beneficial outcomes for all participants, rather than fall into the trappings of single path solutionism. We acknowledge that multiple pathways for RI in eID systems can be developed and our framework provides a guide to help develop these pathways.

Figure 1. The digital identity ecosystem.

The proposed framework below is built not only on RI principles, but also substantiated by the extant eID literature that highlights current issues with these systems and suggests potential solutions to address them.

5.1. Shared values development (consultation, education, and consent)

End users of eID systems lack an understanding of how and which personal data is collected, processed, and transported across divisional and organizational boundaries.

Developing shared values across the digital ID system stakeholder network provides a means to address this information asymmetry and clarify the contract between the individual and an organization. It aims to develop a common understanding of how a digital ecosystem is expected to work for its stakeholders and dispel myths associated with the use of technologies. Two aspects of shared value development are discussed further: the substantive exploration of priorities and the mechanisms for shared values development.

The substantive exploration of priorities aims to untangle the relevant normative and contextual ethical issues. Normative anchors provide philosophical grounding for cooperation between technology and society in achieving set outcomes. Von Schomberg (Reference Von Schomberg2013) provides an example of how “by anchoring on addressing global grand challenges,” the Lund Declaration provides guidance on key normative issues for the European Union to tackle. For eID systems, and ICTs in general, anchoring on UN Declaration of Human Rights provides a starter for engaging on core issues around privacy, autonomy, and security (United Nations, 2015).

Contextual ethical investigation requires an understanding of cultural norms and socioeconomic complexities for the region where an eID system is to be deployed. In Indonesia, children of unmarried mothers can face stigmatization in the process of signing up for ID programmes, creating disincentives in registration (Summer, Reference Summer2015). Women in Nepal, Iraq, Afghanistan, and a number of Middle Eastern states cannot register for identity documents without male presence (Gelb and Metz, Reference Gelb and Metz2018). Addressing these issues requires active engagement with the community and civil society to tackle engendered social divides and also create practical solutions that drive adoption. Engagement on the normative and contextual ethical issues upfront allows for programmes to be more specific and gain greater buy-in.

Shared values development on programmes can be done through consultation, education, and consent. Consultation forums enable engagement with the public on goals and outcomes of the programme. Ideally, they allow for consumers/citizens to understand institutional aims and provide feedback that can be incorporated into large scale ID programmes. In large national ID programmes, the need for speed and efficiency can trump local requirements. Ramnath and Assisi (Reference Ramnath and Assisi2018) suggest that the ingenuity of Aadhaar lay in its “start-up” culture and rapid speed of development and deployment without being hindered by bureaucracy or participatory design—an ideal not dissimilar from Facebook’s (now defunct) disruption motto to “move fast and break things.” Since its deployment, Aadhaar has been mired in judicial debate and civil protests as a violation of fundamental rights.

Public consultations can also provide an avenue for education. Baker and Rahman (Reference Baker and Rahman2020) cite numerous examples of myths that propagate around eID systems in refugee settings: in Ethiopia and Bangladesh iris scans were assumed to be eye check-ups as part of refugee registration, Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh equated their new ID card to a change in their legal status as “officially UNHCR’s responsibility” (Baker and Rahman, Reference Baker and Rahman2020, p. 81). Identification programmes may be carried out with limited education on digital rights of marginalized communities or due processes to appeal for change. The rejection of a proposed Swiss National eID scheme via referendum highlights another unique method for public participation in shaping the contours of an eID programme (Geiser, Reference Geiser2021). While citizens arenot averse to a national eID, they cited discomfort in the proposal that gave primacy to private sector companies in deploying the system. Through the referendum and public consultation, civil society groups argued the need for greater government ownership of the overall programme.

Private sector actors may see public consultation as a risk to their business model or to proprietary information. However, it can be a means to gather data on the preferences of targeted consumer groups, and lead to improved design features, the creation of new markets and innovative services centered around user design features (Friedman, Reference Friedman1996).

Meaningful consent methods are seen as a barrier to a seamless experience in the online ecosystem and privacy policies are shrouded in vagueness. Consent may also be missing in national ID programmes where governmental departments assume that citizens showing up for registration implies consent (Baker and Rahman, Reference Baker and Rahman2020). Effective consent management strategies require eID system providers to provide transparency on data processing practices not just at initial registration to a service, but also as personal data is processed across services and moved across organizational boundaries, throughout the lifecycle of this interaction (Flick, Reference Flick2016; Gainotti et al., Reference Gainotti, Turner, Woods, Kole, McCormack, Lochmüller, Riess, Straub, Posada, Taruscio and Mascalzoni2016). Responsible design choices such as a “default opt-out” can help reduce unapproved data sharing practices. As mentioned in Section 3.2, information asymmetry and framing effects need to be accounted for to ensure consent is effective. Data cooperatives, data commons and data trusts provide a collective means for organization and handling consent in the face of informational asymmetry (Ruhaak, Reference Ruhaak2019, Reference Ruhaak2020; Dutta, Reference Dutta2020). Rather than dwell on a “one-size-fits-all” approach, consent mechanisms require a contextual understanding of the eID ecosystem, and the stakeholders involved.

eID systems are constantly evolving, either in functionality, partnerships, technology or user base, and shared values development practices should be applied on a recurring basis. The nature of intervention may depend on the changes in the system (expansion of services) or changes in the demographics of the user base. Shared values development builds trust between organizations and individuals with differing interests and incentives. Through substantive exploration, complex ethical issues can be identified early and discussed collaboratively. However, trust can also be eroded if the exploration or engagement are merely marketing gimmicks or check-box exercises (Sykes and Macnaughten, Reference Sykes and Macnaughten2013; Corbett and Le Dantec, Reference Corbett and Le Dantec2018).

5.2. Design imperatives (privacy, autonomy, trust, security, and local norms)

Technology design shapes interactions between individuals and organizations. Moral considerations should be articulated early in design (Hoven, Reference Hoven2013). Shared value development elicits stakeholder considerations that are important for the design, development and operations of digital ID systems.

Current practices prioritize speed and standardization, rather than a deliberative assessment of design principles that fit user needs. Refugee ID programmes have generally followed a standard process for identification that includes full biometric verification along with photographs. In countries where photographing women without face coverings is not permitted by social mores, this can cause unrest and discomfort (Baker and Rahman, Reference Baker and Rahman2020). Digital platforms, through their architecture, can perpetuate existing social biases—such as political divisions and racial and gender based inequalities (Boyd, Reference Boyd2011). Biases of designers/network architects spill over into the design of technology solutions, where the participating population is more diverse. Not catering to diverse user needs can lead to exclusions which have negative socioeconomic consequences for the user and the provider.

Value sensitive design (VSD) incorporates ethical values into the design process of ID based systems (Friedman, Reference Friedman1996; Hoven, Reference Hoven2013; Winkler and Spiekermann Reference Winkler and Spiekermann2018). VSD provides a framework to identify direct and indirect stakeholders, understand their needs through interviews/user engagement strategies and develop technical implementations that address and uphold stakeholder values. Contact tracing application have shown how technical designs are heavily influenced by who is involved in the design process and how stakeholders exert their values on technical design decisions (Edwards, Reference Edwards2020; Veale, Reference Veale2020). VSD methods can bring forth value tensions, an important aspect to consider in large scale digital ID programmes. Privacy of an individual, for instance, may be at odds with national security or health monitoring requirements. While not all value tensions result in technical trade-offs, bringing them forward in debate allows for the development of broader sociotechnical solutions to address risks and divergent stakeholder requirements.

Design considerations also require a holistic understanding of how different stakeholders will engage with the system. Technical design choices may require unique social processes to complement them. The choice of biometrics enrolment alone in Aadhaar aims to address duplication risks but excludes manual laborers and older people (Rashid et al., Reference Rashid, Lateef, Balbir, Aggarwal, Hamid and Gupta2013). Similarly, expediting technology deployment, such as contact tracing applications, to entire populations, ignores the exclusionary effect it can have on marginalized, poor or digitally untrained populations (Daly, Reference Daly2020; Edwards, Reference Edwards2020).

Local norms and entrenched cultural practices need to be understood and factored into ID system design. Married women in developing countries may be discouraged from enrolling into ID programmes on the basis that it might lead to greater financial independence and an increase in divorce rates (Gelb and Metz, Reference Gelb and Metz2018). Cultural norms cannot be tackled by technical solutions alone but require intersectional solutions and multidisciplinary thinking. A commitment to review and adapt designed solutions based on new information is imperative to ensure the right outcomes are achieved. In India, Rajasthan’s “Bhamashah Yojana” aimed to address women’s exclusion from government programmes by mandating that all financial aid be sent to the bank account of the woman of the household. While this increased women’s Aadhaar and bank account enrolment, it failed to account for their lack of literacy and social independence. Only 18% of women conducted financial transactions, with the men of the household conducting financial transactions in the women’s name (CGD, 2017).

5.3. Multilevel governance practices

Digital identification happens in various forms: through dedicated programmes, through devices and platforms, through data sharing agreements and through data aggregation. Existing business models evolve through acquisition (such as Facebook and Instagram) and integration (across siloed national ID programmes). Personal data may be used across contexts (e.g., photographs in national ID programmes being run against facial recognition technologies). New methods for identification continue to be developed such as voice recognition, ear recognition, multimodal identification methods and so forth (Frischholz and Dieckmann, Reference Frischholz and Dieckmann2000; Rashid et al., Reference Rashid, Mahalin, Sarijari and Aziz2008; Gandy, Reference Gandy2011; Anwar et al., Reference Anwar, Ghany and Elmahdy2015; Madianou, Reference Madianou2019). Interventions in addition to regulation are required to address the multitude of aforementioned changes.

Hellström (Reference Hellström2003) suggests a national level clearing house for the development of emerging technologies that brings together various stakeholders to define a future course of action for a technology. This allows for reflection and assessment of different digital identification methods. In 2017, the European Parliament endorsed the establishment of a digital clearing house to aid greater collaboration between national regulatory bodies—a welcome step in developing interdisciplinary and multinational alignment across regulatory regimes. Ethical impact assessments and privacy audits provide tools to assess the risks associated with ID technologies usage in different sectors. A national certification process for privacy assessments aligned to global standards (such as ISO 27701 and 27001, IEEE P7002) may enable private sector capacity development, reducing the burden of regulatory implementation and monitoring on government entities.

At national and international levels, governments can direct research and innovation in societally beneficial areas through the development of policy, alignment to normative development goals, allocation of funding, and enabling deliberation from researchers and entrepreneurs on societal outcomes of their research (Fisher and Rip, Reference Fisher and Rip2013; Von Schomberg, Reference Von Schomberg2013). In the EU and through UK Research Councils, researchers are asked to consider the societal impact of their research in order to gain funding (Fisher and Rip, Reference Fisher and Rip2013).

At an organizational level, interventions that force deliberation and reflexivity can be introduced. Designers with technical backgrounds (or technology corporations) may default to technological solutions when trying to address socioeconomic problems (Johri and Nair, Reference Johri and Nair2011). Micro-level interventions such as training courses, dedicated social science researchers per project team and interdisciplinary approaches to problem development can help reduce a techno-deterministic bias in solution design. Additionally the use of heuristic tools and practices may reduce the influence of designer biases (Umbrello, Reference Umbrello2018). Introducing social sciences and ethics-based training to engineering and design college curriculums also help future designers think about complex issues through diverse perspectives.

5.4. Organizational structure and commercial arrangements

In the context of eID ecosystems, transparency on technologies deployed, commercial arrangements, organizational structures and incentives can build trust in the system. These aspects are often overlooked or trumped by economic considerations.

Nigeria’s digital ID programme was launched in 2014 with a plan to integrate multiple siloed identification databases across the government. The government partnered with Mastercard and Cryptovision in an effort to integrate identification with payments (Paul, Reference Paul2020). While the overall project has faced delays, the partnership with Mastercard has raised concerns on the commercialisation of sensitive personal data (Baker and Rahman, Reference Baker and Rahman2020). Existing low trust in government is exacerbated by partnership with a commercial entity and limited transparency on the details of their partnership (Hosein and Nyst, Reference Hosein and Nyst2013).

As experienced globally in COVID-19 response strategies, public sector programmes can rely on the private sector to deliver services, without transparency on partner selection processes or arrangements on data sharing (Daly, Reference Daly2020). High value technology purchases may be made on a limited assessment of the ability of a government agency to implement the technology. It can lead to issues of vendor lock-in to maintain complex and unnecessary infrastructure (Gelb and Metz, Reference Gelb and Metz2018).

Inter and intra departmental data sharing arrangements also need to be made transparent. Aadhaar data is used across several state and central government programmes. There have been multiple instances of sensitive personal data being leaked on partnering government websites (Sethi, Reference Sethi2017; Business Standard, 2018; Financial Express, 2018; Saini, Reference Saini2018).

Understanding and controlling for private sector incentives can be complex. Of the 2.9 billion Facebook users only 190 million live in the USA, while approximately 80% of its shareholders are based in the USA (CNN, 2020; Statista, 2020). Over 50% of its revenues come from advertising spend outside the USA (Johnston, Reference Johnston2020). Maximizing American shareholder returns is implicitly linked with the need for advertising growth in foreign countries, coming at the cost of a potential loss of privacy for individuals in countries without necessary legal protections. Additionally, revenues made from these countries are repatriated without tangible benefits to their societies.

23andMe is a private company headquartered in the USA, offering mass genetic testing kits. In January 2020, it raised $300 million by partnering with GlaxoSmithKline in a data sharing agreement to build new drugs. 23andMe collects genetic data from the use of their $69 test kits and digital data from their user’s online activity. Their terms of service require users to acknowledge that, by consenting to using 23andMe services, they will not be compensated for any of their data (23andMe, 2020). 23andMe’s business model is built on data aggregation, analysis and sharing while its marketing campaign focusses on health benefits of knowing your genetic make-up. The scientific evidence on improving health outcomes based on DNA matching is ambiguous at best (Stanton et al., Reference Stanton, Robinson, Kirkpatrick, Farzinkhou, Avery, Rigdon, Offringa, Trepanowski, Hauser, Hartle, Cherin, King, Ioannidis, Desai and Gardner2017). 23andMe claims that the data they share is aggregated and anonymized and that the creation of their database provides a means to improve societal health outcomes. Even by removing identifying attributes, individuals can quite easily be reidentified using genetic data (Segert, Reference Segert2018). As 23andMe is a paid service, it invariably excludes those unable to participate due to financial constraints. 23andMe is open to sharing data with private enterprises while explicitly refusing to share data with public databases or law enforcement.

Data sharing is made possible through the use of APIs. APIs act as the nuts and bolts of data sharing enabling the commercial agreements between organizations. By default, APIs on Facebook allow access to a user’s basic ID data (name, location, and gender) and then a choice of over 70 data fields that help describe a user (for e.g., check-ins, relationship status, events, friend’s interests, and video uploads) (Pridmore, Reference Pridmore2016). After an initial approval by the user this API remains open indefinitely and tracks changes to a user profile or eID across platforms. An individual’s relationship with an application is no longer limited to a one-off usage but is maintained, knowingly or unknowingly, until such time that they use the social media site.

5.5. Autonomy and ownership of the online self

eIDs are associated with a digital data corpus, built between data exchanges by users and digital systems; and the projected self, built through expressions and interactions mediated through social networking platforms (Feher, Reference Feher2019). Problems relating to the digital data corpus are usually viewed as having engineering solutions, for example, how to identify and authenticate someone, what system architecture to deploy, how to keep this data secure and so forth. The projected self is a sociological study of how individuals create and attempt to manage their identities and reputations online. Both aspects are interrelated but are discussed in their own scholastic silos. Understanding both aspects of digital identities is important to ensure maintenance of an individual’s data rights.

All data goes through a lifecycle of creation, maintenance, storage and archival or deletion. EU GDPR provides a mandate on individual’s rights to their data including the right to access, modify, port, and delete data from online platforms. The right to be forgotten, of an EU citizen, only manifests itself in the EU, as GDPR is territorially limited. If the same person were to search for their information while living outside the EU or by VPN to a non-EU server, they would be able to find previously “forgotten” information (Kelion, Reference Kelion2019). We are never truly forgotten in the digital world.

Platforms and digital services may claim that they do not own users’ personal data, yet their practices and policies can be unclear. The largest platforms—Google and Facebook—make the lion’s share of their revenue from contextual and remarketing based advertising that uses its users’ personal data to build targeted advertisements (Esteve, Reference Esteve2017). There are early signs of legislative developments at a state level in the USA, as California passed the California Consumer Privacy Act in January 2020 with better privacy controls for users. Laws for data portability and ownership are also being drafted at the national level (Mui, Reference Mui2019; Eggerton, Reference Eggerton2020).

New models of data ownership and digital services are being developed that challenge transnational platform power paradigms. Barcelona’s technological sovereignty movement moves away from the depoliticization and technocratic rhetoric of smart cities that are driven by global multinationals and toward business models that are transparent, democratic, and owned and run by the community (Lynch, Reference Lynch2020). Data cooperatives offer an avenue to develop business models that exploit personal data responsibly. MIDATA is a data cooperative that pools personal healthcare data for common good and decide what data is used and for what purpose. Data cooperatives offer an opportunity for excluded minority communities to pool resources and benefit from medical research from the use of their data (Blasimme et al., Reference Blasimme, Vayena and Hafen2018).

Identity management on digital media has been compared to Erving Goffman’s definition of stage performance for impression management online (Trottier, Reference Trottier2014; Ravenlle, Reference Ravenlle2017). The management of identities however is not always controlled as social connections can tag content that negatively affects this image. The recordable nature of digital data entrenches this issue, since untagging or deleting inflammatory posts does not eliminate the data from the platform. In fact, users perceive that impression and identity management online is only 70% controlled by the individual (Feher, Reference Feher2019). Alternate social media platforms provide some capabilities to address these issues. MeWe, positioned as an alternative to Facebook, has a privacy by design model and. Its privacy bill of rights states that the individual, not the platform, owns their data. Users have control of their own newsfeed and profile and user permissions are required prior to any posts on a user’s timeline. The platform claims to not track or monetise user content and only partners with third parties that are aligned with its own privacy imperatives (MeWe, 2019). The platform has over 6 million users and a rapid adoption rate, using privacy features as a competitive advantage. Signal and Telegram messenger services have seen similar surges in usage as preferred privacy enhancing alternatives to WhatsApp (Kharpal, Reference Kharpal2021).

5.6. Inclusion, exclusion, and responsiveness to change

The ever-increasing infrastructure of eIDs can have exclusionary effects. Manual workers tend to fail fingerprint scanning technologies significantly more than normal (Rashid et al., Reference Rashid, Lateef, Balbir, Aggarwal, Hamid and Gupta2013; Gelb and Metz, Reference Gelb and Metz2018). Inaccessible government ID registration centers exclude the poor who may not be able to afford a trip to the center or exclude women who arenot able to travel to such centers without a male partner (Gelb and Metz, Reference Gelb and Metz2018; Baker and Rahman, Reference Baker and Rahman2020). Lagging infrastructure investments may mean that vulnerable populations in remote villages do not get food rations due to an unreliable telecommunications signal (Drèze et al., Reference Drèze, Khalid, Khera and Somanchi2017). Older or less digitally savvy consumers may also be excluded from critical business services if delivered solely through digital mediums.

RI provides a framework to think about who benefits from eID systems and who gets excluded and how exclusions can be addressed (Owen et al., Reference Owen, Stilgoe, Macnaughten, Gorman, Fisher and Guston2013; Stilgoe, Reference Stilgoe2013). eID technologies require a means to monitor how they are impacting society and adapting to reduce harms. Programme impact assessments need to go beyond usual volume metrics of coverage and also consider ethical, experiential, and exclusionary dimensions.

Ethical assessments should understand how target populations perceive the use of eID systems, if people understand their rights and how their identities are mediated. Experiential assessments should focus on understanding how users of ID systems affect human agency. Exclusions based assessments should monitor the participation levels of different population segments. For government programmes—are those most in need being served and if not, why not? Are alternate channels for engagement addressing exclusions? For private sector actors—are they missing out on segments of population that do not understand their technology? For example, are older people unable to participate in online purchasing? Are there mechanisms to help them participate safely?

Understanding the ethical, experiential, and exclusionary aspects helps ID systems adapt to current and future needs. It is an iterative process of development by the system provider rather than the current norm where all users have to conform to a standard process. This requires ID system providers to have a commitment to generate, evaluate and act on new information and respond to its stakeholders needs (Petersen and Bloemen, Reference Petersen and Bloemen2015; Brass and Sowell, Reference Brass and Sowell2020).

6. Conclusions

eID systems offer an opportunity for significant socio-economic gains through the development of targeted services to meet people’s needs. Currently eID development and management gives primacy to engineering practices, even though they are part of complex sociotechnical systems. Extant literature highlights that current eID system governance practices are siloed, and rarely aligned across the ecosystem, as they focus on risk management practices limited to addressing known and localized risks without much regard for the networked nature of digital ecosystems. By bringing a systems lens, this article highlights the need for deliberation on how rights, justice and access are mediated through networked digital systems. It progresses the scholarship on data justice through a set of principles that can be operationalized in current or future eID systems.

The proliferation of eID systems across sectors and their importance in digitally enabled economies requires a more forward-looking approach that balances uncertainty and innovation. RI provides an analytical framework to build innovation with care and responsiveness to its stakeholders, supporting the current and future governance of eID systems. The proposed framework in this article acknowledges the networked nature of digital business models and seeks to improve socioeconomic outcomes for all stakeholders through greater deliberation and democratic engagement while governing eID systems.

There is a growing body of knowledge addressing specific issues associated with digital business models, such as privacy enhancing technologies (PETs) to address surveillance risks, self-sovereign identity models to redress the locus of information ownership and improving data lifecycle management practices. In contrast, this article provides a broader principles-driven approach to eID systems governance. The proposed RI framework is not intended to replace existing governance approaches, but to completement current and future approaches to developing and managing eID systems, whether deployed by public, commercial or not-for-profit entities, in a responsible, deliberative, inclusive, and user-centric manner. The proposed framework can be used as an analytical tool to assess existing practices and identify gaps and areas for improvement. While all the principles in our framework may not be relevant to every digital entity or circumstance, it provides practices that can be considered across a variety of contexts.

Future studies can expand on the application of the proposed framework for eID systems in real world settings, in particular highlighting outcomes on trust and socioeconomic benefits achieved through greater stakeholder engagement in governance of eID systems, while considering the power relations and incentives of stakeholders.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Zeynep Engin (UCL Computer Science) for providing invaluable feedback to this work. This article has also been submitted to the Data for Policy 2021 global conference.

Funding Statement

None.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests exist.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: N.A., I.B.; Data curation: N.A.; Formal analysis: N.A., I.B.; Investigation: N.A.; Methodology: N.A., I.B.; Resources: I.B.; Supervision: I.B.; Validation: I.B.; Writing—original draft: N.A.; Writing—review and editing: I.B.

Data Availability Statement

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.