Policy Significance Statement

The use of insights derived from mobile network operators revealed the potential of data science and innovation in supporting evidence-driven crisis response and adoption of targeted policy measures to fight the COVID-19 pandemic. This initiative shows that when the use of privately held data takes place responsibly and is aimed at effectively responding to pressing policy questions, it has the capacity to impact the policy cycle. Even though trust between the involved stakeholders is essential for dealing with this kind of sensitive data, responsible research requires additional verification that, in fact, no harm is created, neither to the assets of the data providers, nor to the legitimate interests of the data subjects involved.

1. Introduction

The new coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) rapidly spread throughout the world during the first quarter of 2020, reaching pandemic status on March 11, 2020. Authorities in most of the European countries and worldwide had to confront with unprecedented challenges to contain the number of infections and prevent saturation of intensive care units in national health systems. This required immediate policy responses. Governments reacted by passing a wide range of measures, including confinement measures designed to contain the spread of the virus, information campaigns, fiscal stimulus to support the economy in the short term, recovery plans for the aftermath and preparation to prospective second waves of the virus. The need for timely, accurate, and reliable data that would inform such decisions is of paramount importance.

Against this backdrop, on April 8, the European Commission asked European mobile network operators (MNOs) to share anonymized and aggregate mobile positioning data. The aim was to provide mobility patterns of population groups and serve the following purposes in the fight against COVID-19. Initiated by means of an exchange of letters, the terms of cooperation between MNOs and the European Commission are outlined by a Letter of Intent,Footnote 1 which specifies that insights into mobility patterns of population groups extracted in the framework of this initiative are meant to serve the following purposes:

-

1. understand the spatial dynamics of the epidemics thanks to historical matrices of mobility national and international flows;

-

2. quantify the impact of social distancing measures (travel limitations, nonessential activities closures, total lock-down, etc.) on mobility;

-

3. feed Susceptible-Infectious-Recovered (SIR) epidemiological models, contributing to the evaluation of the effects of social distancing measures on the reduction of the rate of virus spread in terms of reproduction number (expected number of secondary cases generated by one case);

-

4. feed models to estimate the economic costs of the different interventions, as well as the impact of control extended measures on intra-European Union (EU) cross border flows and traffic jams due to the epidemic; and

-

5. cover all Member States in order to acquire insights.

The aim of the initiative was in line with the European Commission Recommendation to support exit strategies through mobile data and apps (Commission Recommendation 2020/518, 2020). Adding details on how mobile positioning data can contribute to epidemiological models, the Joint European Roadmap towards lifting COVID-19 containment measures Footnote 2 of April 15 explains that “[…] mobile network operators can offer a wealth of data on mobility, social interactions […] Such data, if pooled and used in anonymized, aggregated format in compliance with EU data protection and privacy rules, could contribute to improve the quality of modelling and forecasting for the pandemic at EU level.” It is worth mentioning that MNO data have successfully been used to study and respond to epidemics in the recent past as, for example in Broadband Commision (2018).

The data sharing initiative is in line with the EU ambition to become a “leading role model for a society empowered by data to make better decisions” as outlined in the Commission’s communication entitled A European strategy for data (COM 2020/66, 2020) released in February 2020 just before the outbreak of the pandemic. This strategy drew from a number of efforts including the High-Level Expert Group on Business-to-Government (B2G) data sharing, set up by the Commission in autumn 2018 and whose members represented a broad range of interests and sectors. In its final report issued in February 2020 (Alemanno, Reference Alemanno2020), the Expert Group called the Commission, the Member States, and all stakeholders to take the necessary steps to make more private data available and increase its reuse for the common good. These previous efforts proved very timely and paved the way for the COVID-19 data sharing initiative.

The European geographical scale of the MNOs involved in this exercise, through the processing of aggregate and anonymized data, aims at the understanding and sharing of best practices across countries, highlighting which mobility policies are the most effective to fight COVID-19. The process applied by the operators transforms the raw mobile dataFootnote 3 into aggregate and anonymized intermediate products (so called origin–destination matrices [ODMs], see Section 2 for more details). These matrices are the products delivered by the MNOs to the Commission. The matrices are not “ready-to-use” indicators, but their level of granularity and their attributes have given the Commission the opportunity to derive from them indicators specifically designed to meet the needs of JRC researchers, the ECDC,Footnote 4 policy-makers and practitioners at EU and Member States level. In addition to the increased flexibility to design indicators tailored to the policy-makers’ needs, this arrangement also gives the possibility to reduce the effect thanks to the greater transparency and control over the process. This results in output indicators that are more usable by policy-makers.

Even though some mobility data derived from social mediaFootnote 5 or mobile app,Footnote 6 location data are openly available, contains rich disaggregations (e.g., walking mobility vs. driving, or categorization of places in retail, parks, etc.) and has global coverage, the MNO data available provide a number of advantages over that location data: level of granularity, both spatial (MNO data reaches up to municipality level while app data available is limited to region or province) and temporal (some MNOs provide more than daily updates); representativity (MNO data probably better captures all the different population groups); availability of connectivity data (i.e., from an origin to a destination, as opposed to just mobility levels at a location); a higher level of transparency (more detailed methodological description). This makes the MNO data a very valuable source of human mobility insights.

The unique nature of the initiative lies in its geographical scope, the number of involved MNOs, and their relatively rapid and in many cases unconditional support offered. Thanks to continuous dialogue with the Commission, MNOs have shown concrete interest in being active and supportive, irrespective of the different levels of maturity in producing the required data; some were already collecting and processing aggregate and anonymized data to deliver similar insights to national authorities, others had to develop ad hoc processes to be in a position to respond to the data request. Within a few months, data from 17 MNOs covering 22 EU Member States plus Norway have been transferred to the Commission on a daily basis, with an average latency of a few days, and in most cases covering historical data from February 2020. This enables the comparative analysis across countries of mobility before, during and after the release of lock-down measures.

2. Mobility Data: Definitions, Harmonization and Comparability across Providers

The urgency of producing useful insights and quickly supporting the response to the crisis, combined with the fact that the initiative is pro-bono, led to the decision of sharing ODM data already available, requiring the least possible additional developments by the MNOs. As expected, the shared ODMs follow definitions and methodologies that inevitably differ among MNOs in various aspects, such as:

-

• Geolocation. Movements are based on the processing of a series of positions obtained through the association to the network antenna to which users are connected, or the centroid of the cell although there are techniques to increase the geolocation accuracy (see Ricciato et al., Reference Ricciato, Lanzieri, Wirthmann and Seynaeve2020a) for a complete overview of different geolocation schemes) MNOs log the communication activity (“events”) between the user’s mobile phone and the network. These events are referred to as call detail records, which include mobile phone calls, messaging, and internet data accesses, or more generally as extended detail records, which also include network signaling data.

-

• Mobility definitions. Several operators register a movement when a user is in a new destination area for a minimum period of time known as “stop time” which might vary across MNOs from 15 to 60 min. A few MNOs use a different approach and record a movement when users spend most of the time within a time window of, for example, 8 h in an area different than the area of the previous time window or the area where they usually spend most of the time during the night. As a result, the same physical mobility pattern can be captured and described by different origin–destination movements depending on the approach adopted.

-

• Extrapolation. Some operators extrapolate the movements counts to the total population based on their market share in the country.

-

• Spatial and temporal resolution of ODMs. MNOs use different types of geographical areas for capturing movements, for example, administrative boundaries (such as municipalities, postcodes, and census areas) or regular geo-grids. Similarly, the time-frequency of the reported movements is heterogeneous, with time-windows ranging between 1 and 24 h.

-

• Confidentiality thresholds. MNOs discards all movements below a given “confidentiality threshold” to reduce de-anonymization risks. This confidentiality threshold is set in adequate proportion to the size of the adopted geographical area of reference (and its lowest population) and thus varies across MNOs.

-

• Syntactic heterogeneity. MNOs deliver ODMs in different data formats, geographic files in different coordinate reference systems and use different languages to describe the data. These syntactic heterogeneity issues are of minor importance compared to the others heterogeneity issues described above and can easily be addressed.

-

• Presence of additional attributes. Some MNOs provide additional information about mobile phone users such as age groups and sex as well as inbound or outbound roamers. As a matter of fact, the more the level of disaggregation or granularity, the more movements fall below the confidentiality threshold and are therefore filtered out.

The large variations of the parameters described above lead to a low harmonization of the aggregate and anonymized data across operators. Through further aggregation and relativization (i.e., concentrating to mobility trends rather than absolute figures), it was possible to use the principle of common denominator to derive from the ODMs a number of mobility data products that preserve a certain amount of basic shared characteristics and are therefore mostly comparable across countries. Through the process of harmonization the ODMs received from the MNOs (and that differ in geolocation, mobility definitions, etc.) are transformed into mobility data products with a higher degree of comparability across MNOs than the original matrices. Although the derived insights have proved extremely useful, constraints of data heterogeneity across operators could be overcome by formulating refined data requests following Trusted Smart StatisticsFootnote 7 concept as in Ricciato et al. (Reference Ricciato, Wirthmann and Hahn2020b), with the results of providing harmonized statistics on human mobility to more effectively feed epidemiological models.

3. First Insights—Mobility Data Products

The first results of the initiative were communicated to the general public by the European Commission daily newsFootnote 8 on July 15, 2020, by DG JRCFootnote 9 and DG CONNECT.Footnote 10 The first results were covered by official channels, such as, nationalFootnote 11 , Footnote 12 and internationalFootnote 13 , Footnote 14 news outlets, medical based newsFootnote 15 and EUreporter.Footnote 16 Messages in social media were positively received.

Three mobility data products have been developed during the first phase of the initiative. The first two, referred to as the Common Denominator, are the result of space–time aggregation and normalization of the ODMs, aimed to provide further safeguard in terms of both users’ privacy and commercial sensitivity of the data, and mostly to allow comparability across countries. The third product, referred to as mobility functional areas (MFAs) allows identifying areas with a high degree of inter-mobility exchange. The three products, which are described in the following paragraphs, are being shared with authorized JRC researchers for COVID-19 related research.

3.1. Mobility indicators

The mobility indicators aggregate further the MNO-provided ODMs to common spatial and temporal granularities, thus allowing for an easier comparison of mobility patterns both in time and across different European countries. The indicator uses the Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS) regions as standardized geographical reference. Specifically, it shows mobility patterns from NUTS0 (country) to NUTS3 level. For a given geographic area, the mobility indicator provides a historical time series of mobility according to the direction of the movements as internal, inwards, outwards, and total. For more information about the mobility indicators and their applications, we redirect the interested reader to Santamaria et al. (Reference Santamaria, Sermi, Spyratos, Iacus, Annunziato, Tarchi and Vespe2020).

3.2. Connectivity matrix

The connectivity matrix, similarly to the mobility indicators, aggregates further the ODMs to a common space–time granularity. Unlike the mobility indicator, the connectivity matrix provides information about bilateral movements between areas. The indicator adopts a weekly time frequency (separating between week days and weekend mobility), and uses the NUTS3 regions as a geographic reference. For more information about the connectivity matrix and its applications, we redirect the interested reader to Iacus et al. (Reference Iacus, Santamaria, Sermi, Spyratos, Tarchi and Vespe2020a).

3.3. Mobility functional areas

The MFAs are data-driven geographic zones with a high degree of inter-mobility exchange. The construction of the MFAs, which is completely data-driven, starts from the ODMs at the highest spatial granularity available irrespective of administrative borders. The construction of the daily MFAs consists in identifying, through a network analysis approach, disjoint clusters of origins and destinations, that is subsets of the ODM, that exchange a high number of movements among them. Some of the MFAs change daily following mobility patterns. The intent MFAs, called simply MFAs, are obtained through the fuzzy intersection of the daily MFAs. The rationale behind the MFAs is that the implementation of different physical distancing strategies (such as school closures or other human mobility restrictions) based on MFAs instead of administrative borders might lead to a better balance between the expected positive effect on public health and the negative socio-economic impact as discussed in Iacus et al. (Reference Iacus, Santamaria, Sermi, Spyratos, Tarchi and Vespe2020b). As an example, it has been possible to see that the number of COVID-19 cases follow geographical patterns similar to the shapes of the MFAs. This is qualitatively shown in Figure 1 for Austria, and further analyzed in Iacus et al. (Reference Iacus, Santamaria, Sermi, Spyratos, Tarchi and Vespe2021a), suggesting that policy measures could be effectively taken on the basis of MFAs rather than on administrative borders.

Figure 1. Number of cases in previous 7 days for the dates March 15 and 31 (top), April 15 and 30, 2020 (bottom) over mobility functional areas (MFAs) in Austria. The COVID-19 geographic spread seems to follow MFAs more than the number of political districts (GKZ) borders (Iacus et al., Reference Iacus, Santamaria, Sermi, Spyratos, Tarchi and Vespe2021a).

3.4. Outreach

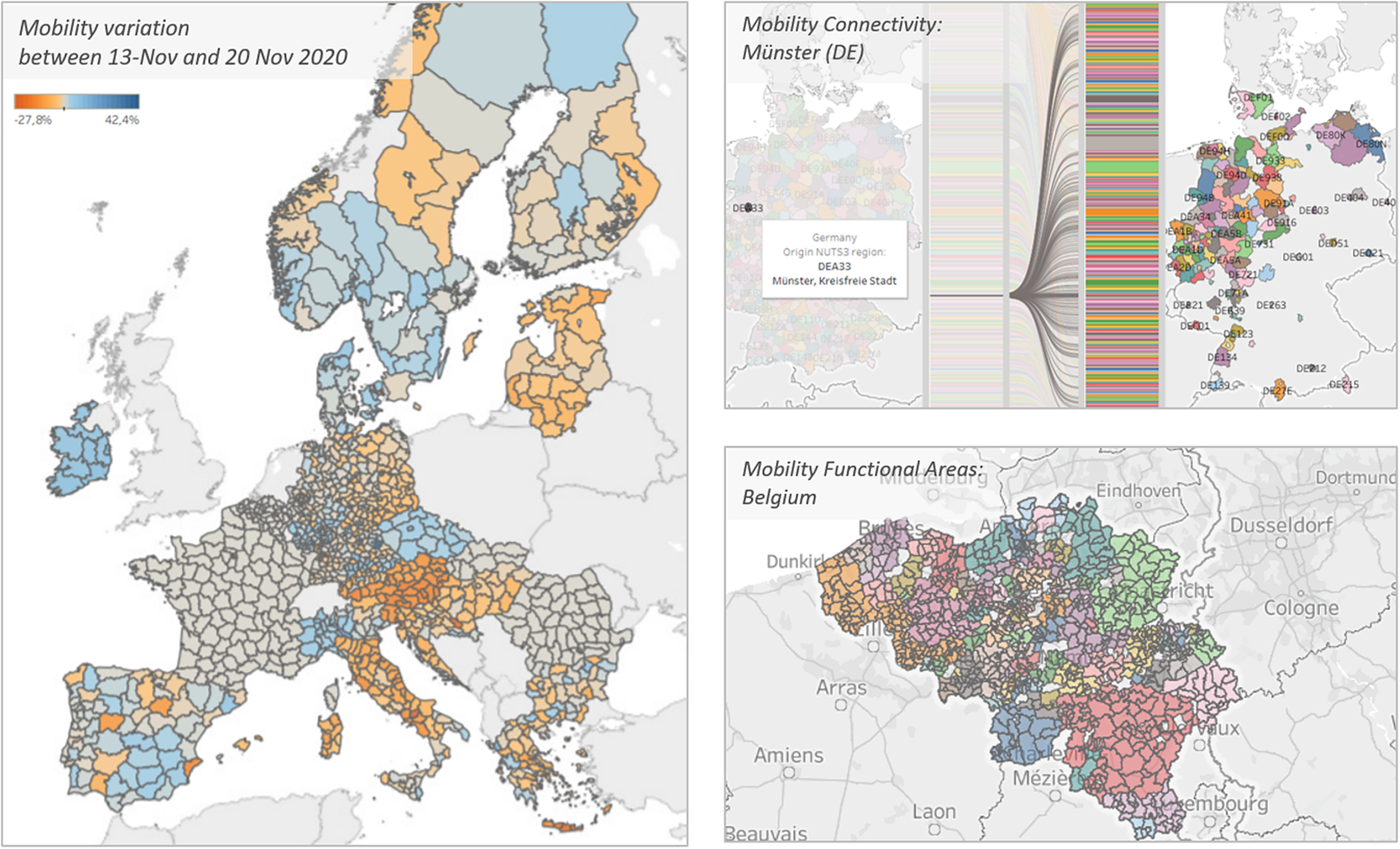

The products are currently feeding the mobility visualization platform (Figure 2), specifically developed to facilitate the access to the insights derived for the benefit of EU Member States, in particular through the eHealth Network.Footnote 17 Moreover, the Staying safe from COVID-19 during winter strategy adopted by the European Commission in December 2020 mentions: “Insights into mobility patterns and role in both the disease spread and containment should ideally feed into such targeted measures. The Commission has used anonymized and aggregated mobile network operators’ data to derive mobility insights and build tools to inform better targeted measures, in a mobility visualization platform, available to the Member States. Mobility insights are also useful in monitoring the effectiveness of measures once imposed.” (COM 2020/786, 2020).

Figure 2. The mobility visualization platform allows the access and visualization of the three products (left: mobility indicators, top right: connectivity matrices, and bottom right: mobility functional areas), presenting insights comparable at national, regional, and Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS)3 level and combining ECDC data. Access to the platform is provided to practitioners and policy-makers in the Commission, ECDC, and European Union (EU) Member States.

The products are currently being expanded to feed early warning mechanisms to detect anomalies in usual mobility patterns such as gatherings (Iacus et al., Reference Iacus, Sermi, Spyratos, Tarchi and Vespe2021b) and to inform scenarios for targeted COVID-19 nonpharmaceutical interventions (De Groeve et al., Reference De Groeve, Annunziato, Galbusera, Giannopoulos, Iacus, Vespe, Rueda-Cantuche, Conte, Sudre and Johnson2020).

4. Challenges and Recommendations for the Future

Because of its unprecedented nature, this B2G initiative highlighted some complex challenges that need to be addressed in order to benefit from the lessons learned. The most relevant challenges are listed below by main domain.

-

1. Data security and integrity. Security and integrity of the data were primarily addressed by implementing end-to-end encryption to the data transferred from the MNOs to the JRC, and by developing a dedicated secure platform to host and process the data which is accessible by a limited and controlled number of users. Data received by the MNOs at high spatial and temporal resolution was not allowed to exit the secure platform. All the data processing, analysis, and storage took place remotely on the Unix secure platform using open-source technologies such as Python, R, and PostgreSQL. The common denominator resulting from this process is represented by the mobility data products presented in Section 3.

-

2. Privacy, commercial sensitivity, and fundamental rights. Data privacy, risk of re-identification of groups of individuals, and ethical aspects related to the use of the data needed to be carefully addressed. Although the data shared by the MNOs (ODMs) contains only anonymized and aggregate data, in compliance with the EDPB guidelines (EDPB, 2020) the JRC carried out a so-called “reasonability test” upon the reception of preliminary data samples from MNOs. The objective of the test is twofold: to actively verify that the data specification in terms of origin destination aggregate data were respected and to assess whether or not the risk of re-identification of the individuals was reasonably low. Following the recommendations by the European Data Protection Supervisor, the JRC Data Protection Coordinator and the GSMA COVID-19 Privacy Guidelines (GSMA, 2020), and in order to respect fundamental rights, avoid discrimination as well as respect of legitimate business interests of operators, the JRC put in place measures such as: (i) definition of conditions of nondisclosure and use of the data products only in well identified COVID-19 related fields (as set out in the Letter of Intent; see Section 1); (ii) limited and controlled access not only to the original MNO data, but also to the derived products; and (iii) adoption of a data retention horizon.

-

3. Communication and transparency. Communication aspects were duly analyzed in order to appropriately convey the message that the initiative has dealt exclusively with anonymized and aggregate data, ultimately avoiding reputational damage both for the MNOs and the Commission as well as political backlash. This required consultation with MNOs and the GSMA prior the publication of communication outlets as well as scientific results to the public.

-

4. Data heterogeneity. Because of the need to react quickly to an emergency situation, the initiative has been based mostly on data already available at the MNOs. Yet, the JRC had to cope with a high degree of heterogeneity of the data as introduced in Section 2. This implied substantial downstream technical efforts by the JRC to harmonize the data to the greatest possible extent, and to find a common denominator across operators resulting in lowered information content but guaranteeing data comparability.

This unprecedented initiative demonstrated the importance of an inter-disciplinary approach, gathering together lawyers, epidemiologists, telecommunication engineers, data scientists, software developers, communication specialists, and policy-makers to face all the different relevant aspects (legal, scientific, technical, communications, etc.). Well-established data stewardship skills are required for successful B2G initiatives within the private, policy, and scientific sectors.

Beside all these considerations and recommendations, a question still remains unanswered: what else can we do to strengthen the preparedness for future pandemics? It has been clear from this exercise that a fast and systematic response is necessary to face future crisis situations. Updated protocols and guidelines need to be already in place at the time of the crisis to avoid potential deadlocks. In this vein, the recent Proposal for a Regulation on European data governance (Data Governance Act; COM 2020/767, 2020) aims to foster the availability of data for use by increasing trust in data intermediaries and by strengthening data-sharing mechanisms across the EU.

The followings are a set of possible recommendations for future similar initiatives aiming at harnessing the potential of mobility insights for policy:

-

1. Establish a Multi-disciplinary Working Group of Experts (telecommunication engineers, data scientist, epidemiologists, lawyers, data protection and ethics experts, IT security experts, modelers, and statisticians) to draft data specification on standardized mobility data addressing scientific challenges and to develop data security and protection protocols and avoid unilateral points of view.Footnote 18 Such interdisciplinary working group should also suggest the right balance between privacy-compliance and level-of-detail starting from the raw mobile positioning data; this may serve the MNOs to find a common standard for the ODMs, drastically reducing the heterogeneity. At the same time, the standards should not be too prescriptive to keep MNOs from innovating. Moreover, the working group should develop additional mobility data products tailored to their different applications (epidemiological modeling, forecasting of the contagion on different scales, mobility-impact assessment, drop in connectivity and tourism, etc.).

-

2. Establish an Ethic Committee with the mission of considering all ethical aspects and implication of the initiative and to make sure that it complies in any of its part with fundamental rights. The Ethics Committee should take into consideration the culturally shared privacy norms of different countries involved in the initiative.

-

3. Establish a Communication Team where all the players involved in the initiative are represented; the team should be responsible to define an appropriate communication strategy for the initiative and its scientific results to the general public. The team should consider the high sensitivity of the topic, safeguarding the reputation of both the involved institutions and the private partners, while preventing misconceptions and misunderstandings about the use of mobile phone data.

-

4. Draft a risk assessment pointing out all possible risks in the various stages of the initiative and defining their likelihood, their possible impact on the success of the project and their mitigation strategies. The risk assessment allows anticipating most of the possible faux pas, carelessness, or mistakes that might jeopardize the success of similar initiatives. The risk assessment should address security, privacy, and ethical threats, with appropriate risk management plan.

-

5. Establish and maintain a Research Network of Collaboration made of data providers, data processors, and data users. Such a network will facilitate the dialog between the parties, ensuring the continuous improvement of procedures and the enhancement of the results.

In terms of highest priority, the ex-ante definition of a common standard for the raw data from the MNOs is indeed the first step, since it requires a long time to be drafted and an even longer time to be implemented. Moreover, its adoption would ensure direct comparability across both regions and mobile data sources, while avoiding the time-and-resource demand in harmonization at the data processor side (see the heterogeneous characteristics of the ODMs explained in Section 2), which not only requires an unavoidable loss of space–time granularity, but very often leads to suboptimal indicators.

Efforts should also aim at making insights and derived products publicly available to the research community in order to make use of its full potential and ensure reproducibility of research outcomes.

5. Conclusions and Next Steps

Based on the results obtained, this initiative can potentially help simplify the systematic use of data from the private sector in the framework of policy support. The global scale and spread of the COVID-19 pandemic highlight the need for a more harmonized or coordinated approach across countries (Oliver et al., Reference Oliver, Lepri, Sterly, Lambiotte, Deletaille, De Nadai, Letouzé, Salah, Benjamins, Cattuto, Colizza, de Cordes, Fraiberger, Koebe, Lehmann, Murillo, Pentland, Pham, Pivetta, Saramäki, Scarpino, Tizzoni, Verhulst and Vinck2020). By collecting mobility data across various EU member states, this initiative is trying to address COVID-19 crisis response in a more holistic way. The initiative provides a concrete example on setting up bilateral channels between private and public sectors in understanding human mobility and providing support in addressing societal issues. Some of the procedures developed during the project should be consolidated in order to speed up future B2G processes. The success of the initiative demonstrates how actors at the interface between the private sector, the scientific community and the policy side can play a key intermediary role in ensuring that data driven insights are used responsibly to effectively respond to pressing policy questions.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of European MNOs (among which 3 Group—part of CK Hutchison, A1 Telekom Austria Group, Altice Portugal, Deutsche Telekom, Orange, Proximus, TIM Telecom Italia, Tele2, Telefonica, Telenor, Telia Company, and Vodafone) in providing access to aggregate and anonymized data, an invaluable contribution to the initiative. The authors would also like to acknowledge the GSMA,Footnote 19 colleagues from EurostatFootnote 20 and ECDC for their input in drafting the data request. Finally, the authors would also like to acknowledge the support from JRC colleagues, and in particular the E3 Unit, for setting up a secure environment to host and process of the data provided by MNOs, as well as the E6 Unit (the “Dynamic Data Hub team”) for their valuable support in setting up the data lake.

Funding Statement

This work received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests exist.

Author Contributions

All authors equally contributed to the work. All authors approved the final submitted draft.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were processed to generate research results presented in the current study.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/dap.2021.9.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.