Article contents

The Origins of Plato's Philosopher Statesman

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Extract

The idea of the philosopher-statesman finds its first literary expression in Plato's Republic, where Socrates, facing the ‘third wave’ of criticism of his ideal State, how it can be realized in practice, declares2 that it will be sufficient ‘to indicate the least change that would affect a transformation into this type of government. There is one change’, he claims, ‘not a small change certainly, nor an easy one, but possible.’ ‘Unless either philosophers become kings in their countries, or those who are now called kings and rulers come to be sufficiendy inspired with a genuine desire for wisdom; unless, that is to say, political power and philosophy meet together, … there can be no rest from troubles for states.’

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1958

References

1 The substance of this article was delivered in the form of a paper at a meeting of the Classical Association in Durham in April 1957.

2 473 bff.

3 325 c ff.

1 Ibid. 334 a.

2 31 c.

1 The Composition of Plato's Apology, 1933, 3. 46, n. 1.

2 500 c.

3 Mem. 1. 6. 14.Google Scholar

1 507 d–508 a.

2 Mem. 4. 7. 2 ff.Google Scholar

3 i.e. moral questions, cf. Aristotle, Met. 1 987b1: ‘S. disregarding the physical universi and concentrating on ![]()

4 I have tried to make a summary of thi in C.Q., N.S. vi. 135 ff.Google Scholar

5 1. 10.

6 ‘Itaque cum Socratem unice dilexisset eique omnia tribuere voluisset; leporem So-craticum subtilitatemque sermonis cum obscuritate Pythagorae et cum plurimarum artium gravitate contexuit.’ For geometry and other branches of mathematics as arts, ![]() cf. Plato, Protagoras 318 d.

cf. Plato, Protagoras 318 d.

7 e.g. Met. 1. 987a29.

1 There is no confirmatory evidence that Plato met Archytas on his first visit, but we only know that he visited Syracuse (Ep. 7. 326 d), and that by chance. Some primary destination must be supposed, and there is none more likely than Tarentum. For Archytas see Diels-Kranz, i, pp. 421 ff.

2 Tim. 20 a, 27 a. I see no good reason for following Cornford and rejecting him as an historical character (Plato's Cosmology, pp. 2 f.).

3 Crotoniate: Diog. 8. 84. 85. At Thebes: Plato, Phaedo 61 d, e, and schol. ad loc, also Plut. de gen. Socr. 13, p. 583a. Tarentine: Vitr. 1. 1. 16, D.L. 8. 46. Taught Archytas: Cic. de orat. 3. 34. 139.

4 The basis for these statements is argued in C.Q., N.s. vi. 135 ff.Google Scholar

1 94.

2 175.

3 254 ff. See Dietrich, Rh. Mus. xlviii. 275 ff.Google Scholar

4 Measurement: 148; geometry = ![]()

![]() 202 f., cf. Horace's characterization of Archytas as maris et terrae numeroque carentis harenae mensor in Odes 1. 28. 1 f.Natural philosophy: the things above the earth 194, 225 ff., 368 ff.; the things below the earth 188; for the form these theories could take and their connexion with

202 f., cf. Horace's characterization of Archytas as maris et terrae numeroque carentis harenae mensor in Odes 1. 28. 1 f.Natural philosophy: the things above the earth 194, 225 ff., 368 ff.; the things below the earth 188; for the form these theories could take and their connexion with ![]()

![]() cf., e.g., Parmenides' system of stephanai. How an account of

cf., e.g., Parmenides' system of stephanai. How an account of ![]() is connected again with an interest in the soul's fate is shown by the myth of Er. See my ‘Parmenides and Er’, J.H.S. lxxv. 59 ff.Google Scholar

is connected again with an interest in the soul's fate is shown by the myth of Er. See my ‘Parmenides and Er’, J.H.S. lxxv. 59 ff.Google Scholar

5 e.g. 260.

6 201 f.

7 1484 ff.

8 The separate peace in the Acharnians, Demus and his servants in the Knights, the imprisonment of the juryman by his son in the Wasps, the Himmelfahrt of the Peace, cloud-cuckooland in the Birds, the women's strike to end the war in the Lysistrata.

9 See C.Q. xxxv. 7.Google Scholar

10 It is to be observed that the four arts attributed to teachers like Hippias are the four divisions of mathematics said by Archytas (frg. 1) to be ![]() and that Plato in the Republic (530 d) says that the Pythagoreans regarded astronomy and music as ‘brother’ sciences.

and that Plato in the Republic (530 d) says that the Pythagoreans regarded astronomy and music as ‘brother’ sciences.

1 285 b.

2 376 e.

3 399 e. See below p. 205, n. 8.

4 400 b; cf. ibid. c.

5 424 c.

1 180 d.

2 282 c.

3 118 b.

4 ![]()

5 For reff. see Schmid-Stählin, , Gesch. Gr. Lit. i. 1, p. 555, n. 5.Google Scholar

6 Laches 180 d.

7 Clouds 967.

8 4. 1.

9 The Alcibiades shows that there is no: contradiction.

10 ![]()

![]()

11 316 e.

2 ![]() Here this undoubtedly means ‘Athenian’.

Here this undoubtedly means ‘Athenian’.

3 As J. and A. M. Adam suggest in the Pitt Press edition ad loc.

4 Wyse, C.R. v. 227, but Sandys, ad loc, gives plenty of examples where a name and its patronymic form are used interchange-ably. There seems no reason to adopt the ![]() given by Steph. Byz. s.v. „Oa, still less to suppose two men, a politician from Oea, and a musician from Oa.Google Scholar

given by Steph. Byz. s.v. „Oa, still less to suppose two men, a politician from Oea, and a musician from Oa.Google Scholar

5 Nicias 6. 3, Aristides 1. 7, Const. Ath. 27. 4.

6 Ath. Mitt, xl (1915), 21.Google Scholar

7 The introduction of payment for jurors at Athens is usually dated 451. Damon is said to have been ostracized after this. The movement against the Pythagoreans in Magna Graecia took place about 450. It is possible that Anaxagoras' persecution belongs to this same period but I am inclined (see C.Q. xxxv [1941], p. 5, n. 2) to regard it as later and as a result of the decree of Diopithes (430).Google Scholar

8 The application of Damon's theories in the Republic leads to reform of the unregenerate primitive society. It has always seemed to me strange that Plato should go through the process of reforming a society which he had only just, so to speak, created. The explanation may be that Damon, like Pythagoras, presented his theories as methods of reform.

1 Aristotle, , Rhet. 2. 23. 1398b9.Google Scholar

2 Hackforth, (The Composition of Plato's Apology, p. 8)Google Scholar dates the Busiris in or about 388, Jebb, (The Attic Orators, ii. 91) in 390 or 391. It certainly antedates the Republic.Google Scholar

3 The references in later literature to Pythagoras' journey to Egypt may well rest on this thinly disguised fabrication.

1 Cic. Tusc. 5. 3. 8, Her. Pont. fr. 88 Wehrli; Diog. Laert. 8. 8.Google Scholar

2 Aristotle, Eng. tr., pp. 97 f.

3 The spectators are ‘genus … maxime ingenuum’. Again ‘ut illic liberalissimum esset spectare nihil sibi adquirentem, sic in vita longe omnibus studiis contemplationem rerum cognitionemque praestare’.

4 D.-K. B 2. 11–12.

5 1. 30. 2.

6 Symp. 8. 39.

1 20. See below, p. 216.

2 Thuc. 2. 40. 1.

3 e.g. fr. 237 ![]()

4 They are pale creatures whom Pheidippides could never join if he is to look his fellow knights in the face again (119–20).

5 485 d.

6 e.g. Plato, , Symp. 219Google Scholar e; Xen. Mem. 1. 2. 2.Google Scholar

7 28 c.

8 Met. M 1078b27.

9 e.g. the Clouds.

10 Mem. 1. 1. 16.Google Scholar

11 304 dff.

1 Tr. W. R. M. Lamb; Loeb ed.

2 Plato the Man and His Work, p. 101. He suggests Antiphon.

3 Phaedrus 278 e.

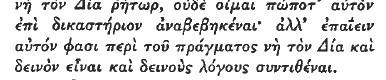

4 See Thucydides 8. 68. 1: in particular the phrase ![]()

![]()

![]() which seems to find an echo in Euthydemus:

which seems to find an echo in Euthydemus:![]()

5 508 a.

1 Od. 3. 363–4.

1 There is much to connect Pythagoras at Croton with the worship of the Muses (see C.Q. N.S. vi. 145Google Scholar f.). There is no direct evidence that the synedrion met in the Mouseion but it is not unlikely. Boyancé, , La Culte des Muses chez les Philosophes Grecs, pp. 237Google Scholar f., argues that it did. For the Muses in the Academy see Boyancé, , op. cit., pp. 248 fF.Google Scholar

1 522 C–531 d.

2 31 c ff.

3 473 b.

4 Trs. by Cornford.

5 Cornford notes (in his translation): ‘this last sentence alludes to the position of Plato himself, after he had renounced his early hopes of a political career and withdrawn to his task of training philosopher-statesmen in the Academy.’ I do not agree. The position described is that of Plato before he was brought to feel that he could realize his political ambitions through the Academy.

1 40 c f.

2 81 a.

3 63 b.

4 See C.Q. N.s. vi. 137.Google Scholar

5 It may have been called geometric because the simplest example of it, 2:4:8:16, exhibits the series of line, square, cube, double-cube.

1 431 d ff.

2 In Cicero's Commonwealth the only duty of the philosophic rector is to produce harmony in the state through imitation of himself. The whole passage De Rep. 2. 42 is an excellent commentary on the ideas we have been considering.

3 Heath, , Greek Mathematics, pp. 84 f. The accepted text of Proclus (on Eucl. I. 65. 19) is now![]() Google Scholar

Google Scholar

4 Iamblichus in Nicom. 100. 19 ff.

1 D–K. 47 B 3.

2 431 d.

3 The three judges, Minos, Rhadaman thus, and Aeacus, ‘will give judgement in the meadow at the cross-roads from which lead the two roads, one to the isles of the Blest, the other to Tartarus’.

4 81 a.

5 Cf. 110 b and 112 c.

6 614c–615a. See my ‘Parmenides and Er’, J.H.S. Ixxv (1955), 65 f.Google Scholar

7 246 e, f.

1 269 C–272 b.

2 20: see Jones, W. H. S., Philosophy and Medicine in Ancient Greece, pp. 16–20.Google Scholar

3 304 dff.

4 96 a.

5 278 e.

1 Met. 1078b 17. Cf. Webster, T. B. L., y, p. 45: ‘Plato passionately desired to give ethical universals the same kind of permanent reality as mathematical universals. This was his interpretation of Socrates' message.’Google Scholar

2 17–18.

3 261 ff.

- 4

- Cited by