No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

The Verb AYω and its Compounds

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Extract

In a recent article Mr. D. A. West investigated the meaning of haurire, haustus, showing how the primary sense ‘to take by scooping, to draw’ is present in a number of passages which have been incorrectly interpreted in the light of extensions made only later of this usage. He noted in passing that ‘this sense may well survive in  , the cognate of haurire’. In this article I hope to show that the recognition of this as the basic sense of

, the cognate of haurire’. In this article I hope to show that the recognition of this as the basic sense of  and its cognates and compounds helps to clear away a number of errors arising from the misunderstanding of the fact that the action of scooping, or drawing, is at the root of Gk.

and its cognates and compounds helps to clear away a number of errors arising from the misunderstanding of the fact that the action of scooping, or drawing, is at the root of Gk.  , as of Lat. haurire.

, as of Lat. haurire.

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1969

References

1 C.Q. N.s. xv (1965), 271–80. I am grateful to Mr. West for criticisms of this article.Google Scholar

2 Geschichte des Perfects im Indogermanischen, pp. 484 ff.Google Scholar

3 Kleine Schriften, pp. 189ff.Google Scholar

1 Cf. Morgan, M.H., De Ignis EliciendiModis apudAntiques, H.S.C.P. i (1890), 13 ff.Google Scholar (addenda by Pease, A.S., C.Ph. xxxiv [1939], 148).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

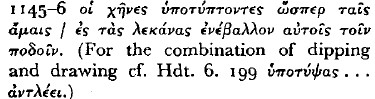

2 Lucian (D.Mar. 2. 2) has an amusing exaggeration of the ![]() usual for such a purpose when his Cyclops says

usual for such a purpose when his Cyclops says ![]()

![]()

![]() . The Hesychian gloss

. The Hesychian gloss ![]()

![]() may refer to the use of a brand by one who

may refer to the use of a brand by one who ![]() .

.

3 Cf. the ![]() used for carrying fire from one point to another in Xen. Hell. 4. 5. 4 and Ar. Lys. 293 ff. So testum in Petron. 136, Ov. Fast. 2. 645, ad Herenn. 4. 6. 9; and the broken pitcher of Isa. 30: 14, which leaves no

used for carrying fire from one point to another in Xen. Hell. 4. 5. 4 and Ar. Lys. 293 ff. So testum in Petron. 136, Ov. Fast. 2. 645, ad Herenn. 4. 6. 9; and the broken pitcher of Isa. 30: 14, which leaves no ![]()

![]() .

.

4 Smoke from dung is recommended in various aspects of bee-keeping in the Geo-ponica (15. 4. 6, ibid. 5. 5, 6. 2).

5 Cf. Plut. Num. 9, Arist. 20, Phoc. 37, Mor. 297 a.

6 Cf. Hdt. 7. 231, Xen. Mem. 2.2.12, Din. 2. 9, Diph. fr. 62, Polyb. 9. 40. 5, Plut. Mor. 538 a, Philostr. Ep. 28, Ael. fr. 245, Dio Chr. 7. 82. On the Buzygian curses see Schulze loc. cit. and the references there cited; also Mnem. xv (1962), 396–8, in connection with Men. Dysc. 505 ff.Google Scholar

1 Op. cit., p. 189.Google Scholar Gf. the new reading ![]() in Callim. fr. 260.69 (H.S.C.P. lxxii [1967], 145).Google Scholar

in Callim. fr. 260.69 (H.S.C.P. lxxii [1967], 145).Google Scholar

2 Reading also ![]() .

.

3 Reading ![]() (in Lyra Graeca i, pp. 162–3).Google Scholar

(in Lyra Graeca i, pp. 162–3).Google Scholar

4 So Jacobs, tibi sumpturus, carpturus inde.

5 For the metaphor cf. Telecl. fr.40 Socrates ![]() for Euripides'phrygians.

for Euripides'phrygians.

6 For this, doubtless common, metaphor cf. Ael. fr.89, D.S.10. 11, 2, Porph. In Harm. p. 26. I8D., and the same use of ![]() in Eunap. V.S. 476

in Eunap. V.S. 476 ![]()

![]() Similarly Horace uses haurireSat. 2. 4. 95 haurire queam vitae praecepta beatae (based on Lucr. 1. 927–8 quoted below).

Similarly Horace uses haurireSat. 2. 4. 95 haurire queam vitae praecepta beatae (based on Lucr. 1. 927–8 quoted below).

7 Basically the same image as ![]()

![]() of Od. 5. 490: cf. flos, semina of fire in Lucr. 1. 900–2, etc.

of Od. 5. 490: cf. flos, semina of fire in Lucr. 1. 900–2, etc.

8 This variant (known to Aristarchus) is quoted by Aesch. schol. ad loc. and Plut. Mor. 934 b.

1 On which epigram see my article Fire Imagery in Two Poems in the Anthology (to appear in Class. Phil.).

2 Rectissime poeta dicitur qui carmina Bacchica ex imo pectore haurit, Kock.

3 Plato mixes these metaphors in Ion 534 b ![]() .

.

4 So too haurire-e.g. Cic. Sest. 93, Apul. Met. 7. 4.

5 It is a little surprising that haurire seems rarely to be used of fire. Ignoring such passages as Virg. Aen. 4. 661 (metaphorical), or Stat. Silv. 2. 1. 24 (also scarcely literal, although cf. Val. Max. 4. 6. 5 ardentes ore carbones haurire), I have noticed only hausto…igne of the Vulgate (Lev. 16: 12, Num. 16: 7) where the Septuagint has ![]() . In [Virg.] Cir. 163 haurire ignem, though metaphorical, comes fairly close to being based on the notion of ‘drawing’ fire.

. In [Virg.] Cir. 163 haurire ignem, though metaphorical, comes fairly close to being based on the notion of ‘drawing’ fire.

6 For the reverse process, using about fire verbs which basically refer to liquid, cf. ![]() (Plat. Leg. 666 a),

(Plat. Leg. 666 a), ![]()

![]() (Crat. fr. 18, as emended by Bergk). Both Schulze and Frisk acknowledge that

(Crat. fr. 18, as emended by Bergk). Both Schulze and Frisk acknowledge that ![]() goes with both nouns here.

goes with both nouns here.

1 Hsch. gives a Laconian form ![]() glossed

glossed ![]() , while

, while ![]() itself he glosses

itself he glosses ![]()

![]() S.v.

S.v. ![]() he gives

he gives ![]()

![]() . Cf. haustrum, Lucr. 5. 516. Hsch. has

. Cf. haustrum, Lucr. 5. 516. Hsch. has ![]() itself as

itself as ![]() -presumably a liquid measure like

-presumably a liquid measure like ![]() (Hdt. 2. 168), another example of

(Hdt. 2. 168), another example of ![]() equivalence. Cf.

equivalence. Cf. ![]()

![]() which Ahrens emended to

which Ahrens emended to ![]() (De Graecae Linguae Dialectis, ii. 55).Google Scholar

(De Graecae Linguae Dialectis, ii. 55).Google Scholar

2 Hermes xl (1905), 154.Google Scholar

3 Ovid has protulit at this point in the story (Met. 8. 460).

4 These ![]() -compounds meaning ‘with draw from underneath’ are antonyms of

-compounds meaning ‘with draw from underneath’ are antonyms of ![]() in (for example) Ar. Eccl. 1031, Telecl. fr. 40.

in (for example) Ar. Eccl. 1031, Telecl. fr. 40.

5 ![]() of drawing off sediment (Protagorid. fr. 4 ap. Athen. 124 c);

of drawing off sediment (Protagorid. fr. 4 ap. Athen. 124 c); ![]() , dehaurio of skimming off scum in Nic. fr. 70. 18, Cato R.R. 66 respectively.

, dehaurio of skimming off scum in Nic. fr. 70. 18, Cato R.R. 66 respectively.

1 For ![]() (winnow) here see my note ‘Cleon and the Spartiates in Aristophanes'; Knights’ (above, pp. 243 ff.).

(winnow) here see my note ‘Cleon and the Spartiates in Aristophanes'; Knights’ (above, pp. 243 ff.).

2 A regular description of meal preparations-cf. Ar. Thesm. 284, Eur. El. 496, Theoc. 14. 17, Callim. fr. 251, etc.

3 So Hor. uses haurire of scooping from a corn bin in Sat. 1. 1. 52 (see West, , loc. cit., p. 272). Incidentally there might be no question of Aristophanes' beans' being cooked at all, let alone singed or parched: they were eaten green for dessert (Athen. 139 a ![]() ), although of course they were also roasted in the

), although of course they were also roasted in the ![]() (Alex. h. 134, Axion. fr. 7).Google Scholar

(Alex. h. 134, Axion. fr. 7).Google Scholar

4 So at least it appears in Kuster's edition (with Lat. aufer), as in Blaydes's and Zacher's apparatus to their editions of the Peace, but no mention of this reading appears in subsequent editions as far as I have been able to ascertain.

1 For a recent discussion of the whole passage see Musurillo, H. in T.A.P.A. xciv (1963), 167–75.Google Scholar

2 Cf. Lucr. 4. 927 cinere ut multo latet obrutus ignis.

3 One thinks of the English use of shuffle (= shovel) of the feet. Aristophanes has a humorous adaptation of this notion in Av. .

.

4 Seidler's emendation ![]() (even if this verb merits recognition-cf. Hsch.

(even if this verb merits recognition-cf. Hsch.![]() ) is not required. The compound

) is not required. The compound ![]() occurs in Nic. Ther. 763 of the down on a moth's wings

occurs in Nic. Ther. 763 of the down on a moth's wings ![]()

![]() and it is interesting to observe the connection with ashes of a verb (meaning ‘touch’ or the like) resembling-and perhaps cognate with-

and it is interesting to observe the connection with ashes of a verb (meaning ‘touch’ or the like) resembling-and perhaps cognate with-![]() , haurio (cf. Buttmann, , trans. Fishlake, , Lexilogus, p. 153).Google Scholar

, haurio (cf. Buttmann, , trans. Fishlake, , Lexilogus, p. 153).Google Scholar

5 ![]()

![]() (Eust. 1547. 63), ‘die sich am Feuer verbrennt’ (Fraenkel, , Geschichte der griechischen Nomina agentis, ii. 39), ‘papillon qui se briile a la lumiere’ (Boisacq).Google Scholar

(Eust. 1547. 63), ‘die sich am Feuer verbrennt’ (Fraenkel, , Geschichte der griechischen Nomina agentis, ii. 39), ‘papillon qui se briile a la lumiere’ (Boisacq).Google Scholar

1 ![]() occurs in the fragmentary fifth line of an epitaph attributed to Phoenix, most conveniently accessible in Knox, 's Choliambic Poets (Loeb), p. 256: the context cannot be determined, but the same metaphor of drawing on a source of inspiration as in Callim. fr. 203 may be employed.Google Scholar

occurs in the fragmentary fifth line of an epitaph attributed to Phoenix, most conveniently accessible in Knox, 's Choliambic Poets (Loeb), p. 256: the context cannot be determined, but the same metaphor of drawing on a source of inspiration as in Callim. fr. 203 may be employed.Google Scholar