Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

In his speech against Meidias Demosthenes describes the arrogant and proud behaviour of his opponent in which Meidias persists in spite of the popular vote condemning him. Whenever there is voting, Demosthenes says, Meidias is put forward as a candidate; he is the proxenos of Plutarch, he knows everything, the city is too small for his aspirations. This illustration of the enormous popularity of an Athenian politician shows his predominant influence in the two spheres of domestic and foreign policy. The main line of this foreign policy —the passage is obviously intended as an accusation—is expressed by the relationship of proxenia and xenia between Meidias and Plutarch, the leading politician of Eretria who, pro-Athenian at first, changed his attitude and almost brought disaster on the Athenian army intervening in Euboea.

1 Dem. 21. 200; cf. 110.

2 Aesch. 3. 86–87.

3 Cf. Aesch. 3. 42. This applies, of course, also to cases of an award of proxenia to a foreigner on the proposal of an Athenian Politician.

4 It is interesting to see that the literary sources—in this case from Herodotus onwards—deal mainly with the political aspects of proxenia. The scholiasts and lexicographers, on the other hand, explain the ‘consular’ activities and duties of the proxenos.

5 Dem. 18. 50–52 clearly tries to minimize: he influence upon his audience of Aeschines' claim to a relationship of xenia with Philip and Alexander. Cf. Aesch. 3. 66. Cf. also [Lys.] 6. 48 and Andoc. 1. 145; 2. 11. When the state is a kingdom the xenos of the king may also be the proxenos of the state, cf. Paus. 3. 8. 4.

6 Aesch. 2. 141; cf. Dem. 18. 82. In his speech ‘For the freedom of the Rhodians’ Demosthenes clearly tries to strengthen his argument by stressing the fact that he is not a proxenos of Rhodes: Dem. 15. 15.

7 See Monceaux, P., Les Proxénies grecques, Paris, 1885Google Scholar; Schaefer, H., Staatsform und Politik, Leipzig, 1932Google Scholar; Wilhelm, A., Attische Urkunden, v. Teil, S.B. Wien, 1942 (220), 5 Abhandlung, pp. 11–86.Google Scholar

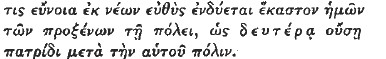

1 That proxenoi were politicians may be concluded from such expressions as ![]()

![]() (I.G. i 2. 27Google Scholar) or

(I.G. i 2. 27Google Scholar) or ![]() (I.G. ii 2. 467).Google Scholar

(I.G. ii 2. 467).Google Scholar

2 [Dem.] 52. 28; cf. 1, 25.

3 Isocr. 15. 93; cf. [Dem.] 52. 14.

4 S.I.G. 3187, 11. 7![]()

![]() Google Scholar

Google Scholar

5 Arist. Pol. 1306a28–33.

6 It is probable that awards of proxenia made by smaller states were comparatively more numerous, cf., e.g., I.G. xii. 5 (1). 542.Google Scholar

7 Cf. also Thuc. 3. 70. 3.

8 Cf. p. 185, n. 3, and Aesch. 3. 33 et sch.

9 Dein, . Ag. Dem. 42–45Google Scholar. Hyper. Ag. Dem, col. 25. Lys. 13. 72 asserts that people pay money in order to get the title of euergetes. Cf. Dem. 20. 132–3. Cf. Plut, . Cim. 14. 4.Google Scholar

10 Dem. 20. 105 ff., 122.

11 Cf. Dem. 20. 57, 64, 105–6, 121; Liban. Hypoth. Dem. 23: ![]()

![]()

![]() Schaefer, , op. cit., p. 26, quotes Thuc. 2. 29. 1 as an example of an award of proxenia aimed at securing future services in this case connected with the establishment of influence in the north in order to safeguard the corn route.Google Scholar

Schaefer, , op. cit., p. 26, quotes Thuc. 2. 29. 1 as an example of an award of proxenia aimed at securing future services in this case connected with the establishment of influence in the north in order to safeguard the corn route.Google Scholar

12 Cf. p. 185, n. 6. Cf. Wilhelm, , op. cit., p. 42. See also Plat. Leg. 642 b:![]()

Google Scholar

Google Scholar

1 Aesch. 2. 172; 3. 138–9; cf. Andoc. 3. 3; (though historically wrong it perhaps contains a grain of truth about the proxenia of Cimon, and certainly shows the popularly accepted notion of connexion between ambassadorial activities and proxenia); Dein, . Ag. Dem. 38; cf. Thuc. 3. 32. 5; 5. 76. 3; 2. 29. I; Xen. Hell. 4. 5. 6; 6. 3, 4; Conon sends a xenos to Dionysius of Sicily, Lys. 19.Google Scholar

2 Hdt. 8. 136; Aesch. 3. 258; cf. Swoboda, H., Arch.-epig. Mitt, aus Österreich, 1893, pp. 53–54Google Scholar. For the date and aims of Arthmius' activities in Greece see Cary, M., C.Q. xxix (1935), 177–80.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

3 Aesch. 2. 89. For proxeniai proposed on the advice of returning ambassadors see I.G i 2. 82Google Scholar; ii2. 8; Tod 135 and perhaps also Tod 132. Assistance to ambassadors given by Strato is recorded in Tod 139. Tod 182 is probably an award to a Macedonian for assistance to Athenian ambassadors at the court of Philip. But the award of proxenia was certainly not made automatically in every case, cf., e.g., Tod 147 and Wilhelm, , op. cit., pp. 23 ff.Google Scholar

4 Plut, . Cim. 14. 4; cf. n. 6.Google Scholar

5 Xen. Hell. 6. 3. 4; cf. 5. 4. 22 (Callias, the grandson of the first).

6 Plut, . Cim. 16Google Scholar. 1–3. The Spartans are interested in promoting or supporting Cimon's influence in Athens. His political programme is based on Atheno-Spartan partnership in the leadership of Greece: Plut, . Cim. 16. 8–10. The name of the Thespian who becomes Athenian proxenos is ![]() in I.G. i2. 36.

in I.G. i2. 36. ![]() is the Spartan proxenos in Plataea, Thuc. 3. 52. 5.Google Scholar

is the Spartan proxenos in Plataea, Thuc. 3. 52. 5.Google Scholar

7 Thuc. 5. 43. 2; 6. 89. 2; Plut, . Alcib. 14Google Scholar; Diog. Laert. 2. 6. 51, 53. For a discussion of the proxenia held by Alcibiades' family and revived by him see Daux, G., Alcibiade proxéne de Lacédémone, Mélanges Desrousseaux, Paris, 1937. PP. 117–22.Google Scholar

1 I.G. i 2. 103. Since a Delian who was given proxenia has no sons, his nephew will inherit it, S.I.G. i3 158.Google Scholar

2 Thuc. 3. 2, 3. Cf. Wilhelm, , op. cit., p. 43Google Scholar; Monceaux, , op. cit., p. 71. For a fourth century Mytilenaean proxenos who stands at the head of the pro-Athenian party there cf. [Dem.] 40. 36.Google Scholar

3 Tod 88.

4 I.G. ii 2. 33.Google Scholar

5 Dem. 20. 59–60, cf. I.G. xii (8). 263Google Scholar. 6; Wilhelm, , op. cit., pp. 18Google Scholar ff., 87 ff. The Athe- nian Cephisophon receives Thasian proxenia c. 341, cf. I.G. xii (5). 114Google Scholar. This is probably in connexion with the danger of Macedon, cf. Feyel, M., Rev. Phil., 1945, p. 151.Google Scholar

6 Tod 98.

7 Another inscription destroyed by the Thirty is I.G. ii2. 52, but the name and country of the proxenos are not preserved. In ii2. 9 and 66 the phrase is restored. I.G. ii2. 448, 11. 61 ff. (318/17) shows that stelae granting honours to foreigners might be destroyed because of internal changes. I.G. ii2. 172 is an award of proxenia to a man whose father was probably awarded it ![]()

![]() The normal procedure was probably then to inscribe the son's name on the father's stele. In this case a new decree had to be passed as the original stele had disappeared; but the circumstances of its disappearance are not known. Other probable cancellations of proxenia are S.I.G. 3 275 and Ael. V. Hist. 14. 1 (Aristotle). Restorations of proxenia in Delphi, cf. S.I.G. 3 292, 294, 295. 300.Google Scholar

The normal procedure was probably then to inscribe the son's name on the father's stele. In this case a new decree had to be passed as the original stele had disappeared; but the circumstances of its disappearance are not known. Other probable cancellations of proxenia are S.I.G. 3 275 and Ael. V. Hist. 14. 1 (Aristotle). Restorations of proxenia in Delphi, cf. S.I.G. 3 292, 294, 295. 300.Google Scholar

1 Tod 181. Cf. also 180.

2 Hyper. Frg. 76, 77 (Jensen) = frg. 19 (Loeb). The proposal of Philippides was also part of this all-out pro-Macedonian effort; Hyper, . Ag. Philipp. 5Google Scholar, refers to the acceptance of the proposals to honour the Macedonians as ![]() Cf. also Ostwald, M., T.A.P.A., 1956, pp. 124–5.Google Scholar

Cf. also Ostwald, M., T.A.P.A., 1956, pp. 124–5.Google Scholar

3 Dem. 8.40; 19.341; 267; cf. Diod. 16.53.

4 Xen. Hell. 1. 1. 35; 3. 18–20; cf. p. 186, n. 11.

5 For the fluctuations and changes in some of these relations see, for example, Demosthenes' speech against Aristocrates.

6 Dem. 20. 59–60; cf. Xen. Hell. 4. 8. 27.

7 Tod 121. For the pro-Athenian activities of Cydon cf. Xen. Hell. 1.3. 18; cf. 2. 2. 1.

8 I.G. ii a. 76Google Scholar. The date cannot be exactly established, cf. Lewis, D. M., B.S.A., 1954, P. 33.Google Scholar

9 Tod 160 = S.I. 3201.Google Scholar

10 Tenedos was pro-Athenian and remained all through a faithful ally, cf. Aesch. 2. 20, 126; Tod 175.

1 I.G. vii. 2407 and 2408 both in c. 364/3.Google Scholar

2 S.I.G. 3158.Google Scholar

3 Tod 152; cf. I.G. xii (5. 2). 1000.

4 Aristophon though awarded proxenia by Carthaea (I.G. xii. 5. 542Google Scholar) was accused of extortion during his strategy, cf. Hyper. ![]() . 28. Cf. Aesch. 1. 107. Cf. sch. Aesch. 1. 64 in Baiter-Sauppe, , Oral. Att. ii. 282.Google Scholars Lys. frg. 78 (Thalheim); Aesch. 3. 223–4.

. 28. Cf. Aesch. 1. 107. Cf. sch. Aesch. 1. 64 in Baiter-Sauppe, , Oral. Att. ii. 282.Google Scholars Lys. frg. 78 (Thalheim); Aesch. 3. 223–4.

6 [Dem.] 7. 38; Dem. 20. 58–60; Aesch. 3. 258; Diod. 13. 27. 3; cf. Lys. 28. 1.

7 Tod 142,11. 28 ff. esp. 3gf. The proxenos is, of course, the head of the pro-Athenian party. Certain decrees of the fifth century threaten the death penalty for the murdei of a proxenos: I.G. ii8. 71 + 38, and I.G. ii 2. 32Google Scholar (cf. Weston, E., A.J.P., 1945, pp. 347–53)Google Scholar. Cf. also I.G. i 2. 28Google Scholar, 72; Wilhelm, , op. cit.: pp. 37–38Google Scholar, and Meiggs, R., ‘A Note on Athenian Imperialism’, C.R., 1949, pp. 9–12.Google Scholar

8 Cf., e.g., I.G. i 2. 118Google Scholar; 55, 149, 154; ii2 110, 133, 77, 252; cf. also I.G. ii 2. 360.Google Scholar

9 e.g. Tod 173.

10 Cf. the veiled scorn in [Dem] 12. 10 at the impotence of Athens to protect Euagoras and Dionysius to whom she awarded citizen-ship. Cf. Tod 109.

10 Dein, . Ag. Dem. 43Google Scholar. Kahrstedt, U., Staatsgebiet und Staatsangehörige in Athen, i, Stuttgart, 1937, pp. 288–9, asserts that an award of proxenia by Athens automatically included a grant of metoikia, thus providing right of sojourn in Athens.Google Scholar

12 For military aid or information: e.g. I.G. ii 2. 27Google Scholar, 133; Tod 116, 143. Citizenship for this reason: Dem. 22. 151, 185, 188; Arist, . Rhet. 2. 23. 1399b1Google Scholar; cf. I.G. ii 2. 17Google Scholar. For economic reasons: e.g. Tod 152; I.G. ii 2. 360.Google Scholar

13 Cf. [Dem.] 12. 8–10 for the diplomatic claims and counterclaims based on an Athenian award of citizenship to Cersobleptes. For ![]() cf. Isocr. 5. 32–37, 76, 116, 170; and the letter of Speusippus to Philip 2–4.

cf. Isocr. 5. 32–37, 76, 116, 170; and the letter of Speusippus to Philip 2–4.

14 Tod 106.

15 Tod 164 a–b; S.l.G. 3266–9 (cf. Aesch. 3. 130 and p. 189, n. 1).Google Scholar