Editorial

EDITORIAL

-

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 15 September 2016, pp. 1145-1150

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

Research

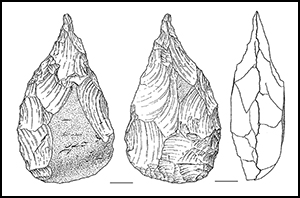

The eastern Asian ‘Middle Palaeolithic’ revisited: a view from Korea

-

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 15 September 2016, pp. 1151-1165

-

- Article

- Export citation

Hunting dogs as environmental adaptations in Jōmon Japan

-

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 15 September 2016, pp. 1166-1180

-

- Article

- Export citation

The Desert Fayum at 80: revisiting a Neolithic farming community in Egypt

-

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 15 September 2016, pp. 1181-1195

-

- Article

- Export citation

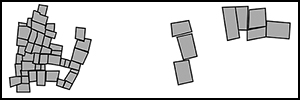

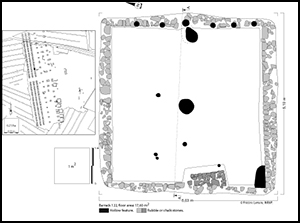

Settlement layout and social organisation in the earliest European Neolithic

-

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 15 September 2016, pp. 1196-1212

-

- Article

- Export citation

How long does it take to burn down an ancient Near Eastern city? The study of experimentally heated mud-bricks

-

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 15 September 2016, pp. 1213-1225

-

- Article

- Export citation

Early pottery in the North American Upper Great Lakes: exploring traces of use

-

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 15 September 2016, pp. 1226-1237

-

- Article

- Export citation

The early history of the Greek alphabet: new evidence from Eretria and Methone

-

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 15 September 2016, pp. 1238-1254

-

- Article

- Export citation

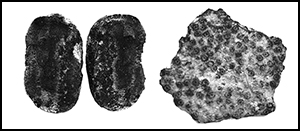

Rice, beans and trade crops on the early maritime Silk Route in Southeast Asia

-

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 15 September 2016, pp. 1255-1269

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

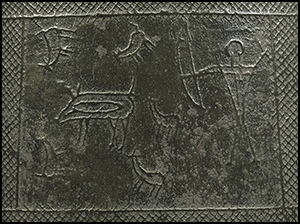

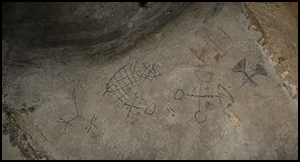

The anthropology and history of rock art in the Lower Congo in perspective

-

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 15 September 2016, pp. 1270-1285

-

- Article

- Export citation

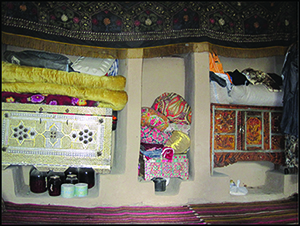

Pottery technology, settlement and landscape in Antofagasta de la Sierra (Catamarca, Argentina)

-

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 15 September 2016, pp. 1286-1301

-

- Article

- Export citation

A GIS-based viewshed analysis of Chacoan tower kivas in the US Southwest: were they for seeing or to be seen?

-

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 15 September 2016, pp. 1302-1317

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

The death of Kaakutja: a case of peri-mortem weapon trauma in an Aboriginal man from north-western New South Wales, Australia

-

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 15 September 2016, pp. 1318-1333

-

- Article

- Export citation

Firewood of the Napoleonic Wars: the first application of archaeological charcoal analysis to a military camp in the north of France (1803–1805)

-

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 15 September 2016, pp. 1334-1347

-

- Article

- Export citation

The archaeology of Anthropocene rivers: water management and landscape change in ‘Gold Rush’ Australia

-

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 15 September 2016, pp. 1348-1362

-

- Article

- Export citation

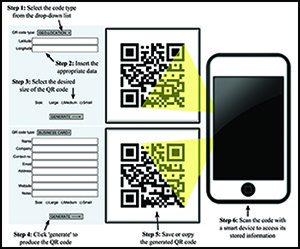

Method

The application of quick response (QR) codes in archaeology: a case study at Telperion Shelter, South Africa

-

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 15 September 2016, pp. 1363-1372

-

- Article

- Export citation

Debate

Doctors, chefs or hominin animals? Non-edible plants and Neanderthals

-

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 15 September 2016, pp. 1373-1379

-

- Article

- Export citation

‘Egypt’: legitimation at the museum

-

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 15 September 2016, pp. 1380-1382

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

Neo-Prehistory—Exist. Regenerate. Repeat?

-

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 15 September 2016, pp. 1383-1386

-

- Article

- Export citation

Review

Gods and scholars: archaeologies of religion in the Near East

-

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 15 September 2016, pp. 1387-1389

-

- Article

- Export citation