Crossref Citations

This article has been cited by the following publications. This list is generated based on data provided by

Crossref.

Morey, Darcy F.

and

Jeger, Rujana

2017.

From wolf to dog: Late Pleistocene ecological dynamics, altered trophic strategies, and shifting human perceptions.

Historical Biology,

Vol. 29,

Issue. 7,

p.

895.

Lupo, Karen D.

2017.

When and where do dogs improve hunting productivity? The empirical record and some implications for early Upper Paleolithic prey acquisition.

Journal of Anthropological Archaeology,

Vol. 47,

Issue. ,

p.

139.

Losey, Robert J.

Nomokonova, Tatiana

Fleming, Lacey S.

Kharinskii, Artur V.

Kovychev, Evgenii V.

Konstantinov, Mikhail V.

Diatchina, Natal'ia G.

Sablin, Mikhail V.

and

Iaroslavtseva, Larisa G.

2018.

Buried, eaten, sacrificed: Archaeological dog remains from Trans-Baikal, Siberia.

Archaeological Research in Asia,

Vol. 16,

Issue. ,

p.

58.

Guagnin, Maria

Perri, Angela R.

and

Petraglia, Michael D.

2018.

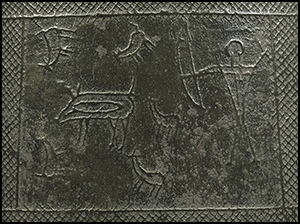

Pre-Neolithic evidence for dog-assisted hunting strategies in Arabia.

Journal of Anthropological Archaeology,

Vol. 49,

Issue. ,

p.

225.

Yeomans, Lisa

Martin, Louise

and

Richter, Tobias

2019.

Close companions: Early evidence for dogs in northeast Jordan and the potential impact of new hunting methods.

Journal of Anthropological Archaeology,

Vol. 53,

Issue. ,

p.

161.

Perri, Angela

Widga, Chris

Lawler, Dennis

Martin, Terrance

Loebel, Thomas

Farnsworth, Kenneth

Kohn, Luci

and

Buenger, Brent

2019.

NEW EVIDENCE OF THE EARLIEST DOMESTIC DOGS IN THE AMERICAS.

American Antiquity,

Vol. 84,

Issue. 1,

p.

68.

Chambers, Jaime

Quinlan, Marsha B.

Evans, Alexis

and

Quinlan, Robert J.

2020.

Dog-Human Coevolution: Cross-Cultural Analysis of Multiple Hypotheses.

Journal of Ethnobiology,

Vol. 40,

Issue. 4,

p.

414.

Koungoulos, Loukas

and

Fillios, Melanie

2020.

Hunting dogs down under? On the Aboriginal use of tame dingoes in dietary game acquisition and its relevance to Australian prehistory.

Journal of Anthropological Archaeology,

Vol. 58,

Issue. ,

p.

101146.

Zhang, Yunan

Zhang, Dong

Yang, Yingliang

and

Wu, Xiaohong

2020.

Pollen and lipid analysis of coprolites from Yuhuicun and Houtieying, China: Implications for human habitats and diets.

Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports,

Vol. 29,

Issue. ,

p.

102135.

Cabral, Francisco Giugliano de Souza

and

Savalli, Carine

2020.

Sobre a relação humano-cão.

Psicologia USP,

Vol. 31,

Issue. ,

Benítez-Burraco, Antonio

Pörtl, Daniela

and

Jung, Christoph

2021.

Did Dog Domestication Contribute to Language Evolution?.

Frontiers in Psychology,

Vol. 12,

Issue. ,

Fish, Frank E.

Sheehan, Maura J.

Adams, Danielle S.

Tennett, Kelsey A.

and

Gough, William T.

2021.

A 60:40 split: Differential mass support in dogs.

The Anatomical Record,

Vol. 304,

Issue. 1,

p.

78.

Venanzi, Lucio González

Prevosti, Francisco Juan

San Román, Manuel

and

Reyes, Omar

2021.

The dog of Los Chonos: First pre‐Hispanic record in western Patagonia (~43° to 47°S, Chile).

International Journal of Osteoarchaeology,

Vol. 31,

Issue. 6,

p.

1095.

Hudson, Mark J.

Bausch, Ilona R.

Robbeets, Martine

Li, Tao

White, J. Alyssa

and

Gilaizeau, Linda

2021.

Bronze Age Globalisation and Eurasian Impacts on Later Jōmon Social Change.

Journal of World Prehistory,

Vol. 34,

Issue. 2,

p.

121.

Pillay, Patricia

Allen, Melinda

and

Littleton, Judith

2021.

Canine Companions or Competitors? A Multi-Proxy Assessment of Human-Dog Competition.

SSRN Electronic Journal,

Pfaller-Sadovsky, Nicole

and

Hurtado-Parrado, Camilo

2021.

A cultural selection analysis of human-dog interactions – A primer.

European Journal of Behavior Analysis,

Vol. 22,

Issue. 2,

p.

248.

Pillay, Patricia

Allen, Melinda S.

and

Littleton, Judith

2022.

Canine companions or competitors? A multi-proxy analysis of dog-human competition.

Journal of Archaeological Science,

Vol. 139,

Issue. ,

p.

105556.

Komatsu, Aya

Cooper, Elisabeth J.

Alsos, Inger G.

and

Brown, Antony G.

2022.

Towards a Jōmon food database: construction, analysis and implications for Hokkaido and the Ryukyu Islands, Japan.

World Archaeology,

Vol. 54,

Issue. 3,

p.

390.

Burza, Laura Brochini

Bloom, Tina

Trindade, Pedro Henrique Esteves

Friedman, Harris

and

Otta, Emma

2022.

Reading emotions in Dogs’ eyes and Dogs’ faces.

Behavioural Processes,

Vol. 202,

Issue. ,

p.

104752.

Carder, Nanny

Crock, John G.

and

Pinto, Audra

2023.

What can osteometric analyses tell us about domestic dogs recovered from a multicomponent indigenous site in Vermont?.

International Journal of Osteoarchaeology,

Vol. 33,

Issue. 2,

p.

196.