No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

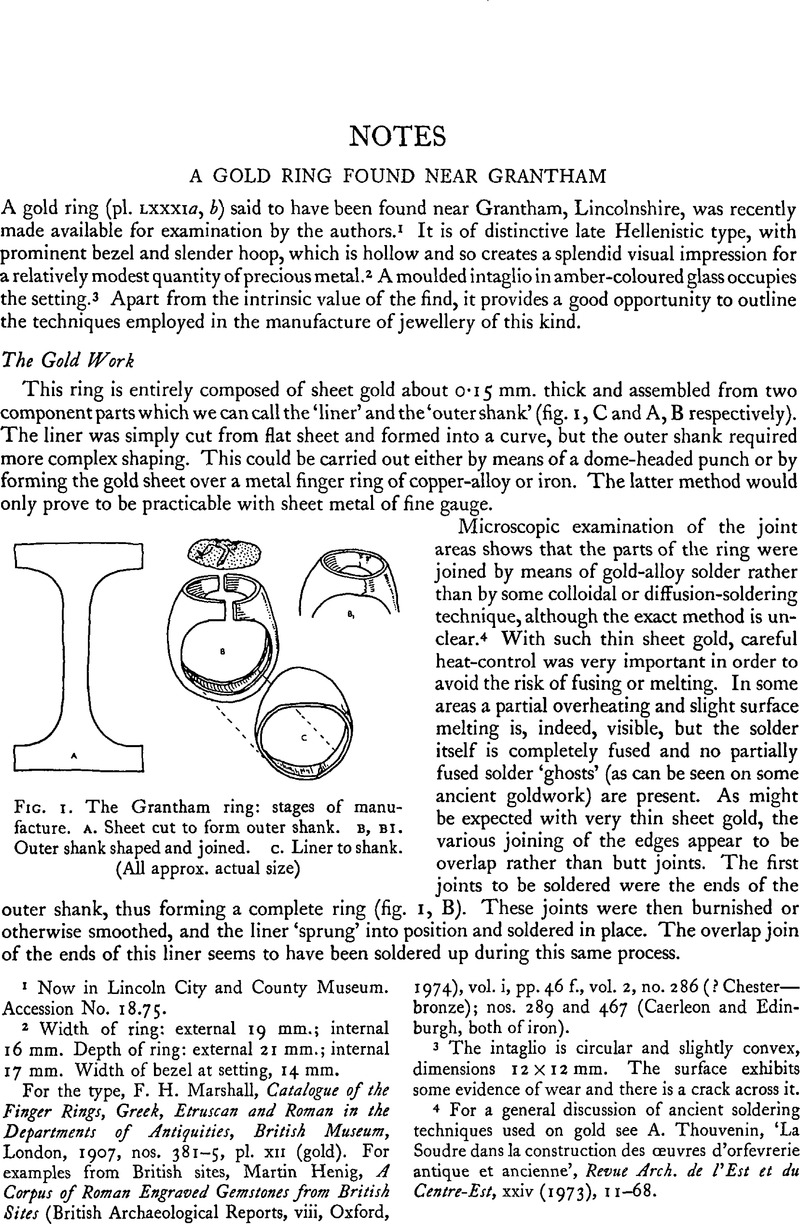

A Gold Ring Found Near Grantham

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 29 November 2011

Abstract

- Type

- Notes

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Society of Antiquaries of London 1975

References

page 382 1 Now in Lincoln City and County Museum. Accession No. 18.75.

page 382 2 Width of ring: external 19 mm.; internal 16 mm. Depth of ring: external 21 mm.; internal 17 mm. Width of bezel at setting, 14 mm.

For the type, Marshall, F. H., Catalogue of the Finger Rings, Greek, Etruscan and Roman in the Departments of Antiquities, British Museum, London, 1907Google Scholar, nos. 381–5, pl. xii (gold). For examples from British sites, Henig, Martin, A Corpus of Roman Engraved Gemstones from British Sites (British Archaeological Reports, viii, Oxford, 1974), vol. i, pp. 46 f.Google Scholar, vol. 2, no. 286 (? Chester—bronze); nos. 289 and 467 (Caerleon and Edinburgh, both of iron).

page 382 3 The intaglio is circular and slightly convex, dimensions 12 × 12 mm. The surface exhibits some evidence of wear and there is a crack across it.

page 382 4 For a general discussion of ancient soldering techniques used on gold see Thouvenin, A., ‘La Soudre dans la construction des ceuvres d'orfevrerie antique et ancienne’, Revue Arch, de l'Est et du Centre-Est, xxiv (1973), 11–68Google Scholar.

page 383 1 Pliny, NH, xxxiii, 25.

page 383 2 We are indebted to Peter Mitchell for assembling and finishing this ring.

page 383 3 Furtwängler, A., Königliche Museen zu Berlin. Beschreibung der geschnittenen Steine, Berlin, 1896, no. 1411Google Scholar.

page 383 4 Richter, G. M. A., Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Catalogue of Engraved Gems, Greek, Etruscan and Roman, Rome, 1956, no. 440Google Scholar (brown glass). P. Gercke, Antike Gemmen in Deutschen Sammlungen, iii, Die Gemmensammlung im Archäologischen Institut der Universität Göttingen, Wies-baden, 1970, nos. 352, 354 (amber-coloured glass).

page 383 5 E. Schmidt, Antike Gemmen in Deutschen Sammlungen, i, part 2, Staatliche Münzsammlung München (italische Glaspasten vorkaiserzeitlich), Munich, 1970, nos. 1571, 1573 (brown glass), 1572 (black glass).

page 383 6 Toynbee, J. M. C., Art in Britain under the Romans, Oxford, 1964, p. 299, pl. LXIXaGoogle Scholar.

page 383 7 Cf. Martin Henig, ‘The Veneration of Heroes in the Roman Army. The evidence of engraved gemstones’, Britannia, i, 1970, 249–65 especially 255, on the significance of the spear in the ethos of the Romans.

page 383 8 Marshall, op. cit., p. xlii, Type C. xxv (= No. 385 from Perugia). For the later type of ring, ibid., p. xlvi, Type E. xvi.

page 384 1 Chiesa, G. Sena, Gemme del Museo Nazionale di Aquileia, Aquileia, 1966Google Scholar. She discusses the rapid increase in gem production and the introduction of glass intaglios at this time.

page 384 2 Todd, M., The Roman Fort at Great Casterton, Rutland, Nottingham, 1968Google Scholar. Whitwell, J. B., Roman Lincolnshire, Lincoln, 1970, p. 12Google Scholar.

page 384 3 Henig, op. cit., vol. i, 47. Todd, op. cit., p. 53, no. 18. Cf. Pliny, NH, xxxiii, 33.

page 384 4 Petronius, Satyricon, xv, 32.

page 384 5 Cope, L. H., ‘Complete Analysis of Gold Aureus’ in Methods of Chemical and Metallurgical Investigation of Ancient Coinage, ed. Hall, E. T. and Metcalf, D. M. (Roy. Num. Soc. special publ. viii (1972)), 307 ffGoogle Scholar.

page 384 6 Brown, P. D. C. and Schweizer, F., ‘X-ray Fluorescence Analysis of Anglo-Saxon Jewellery’, Archaeometry, xv (1973), 175 ffCrossRefGoogle Scholar.