No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 10 March 2017

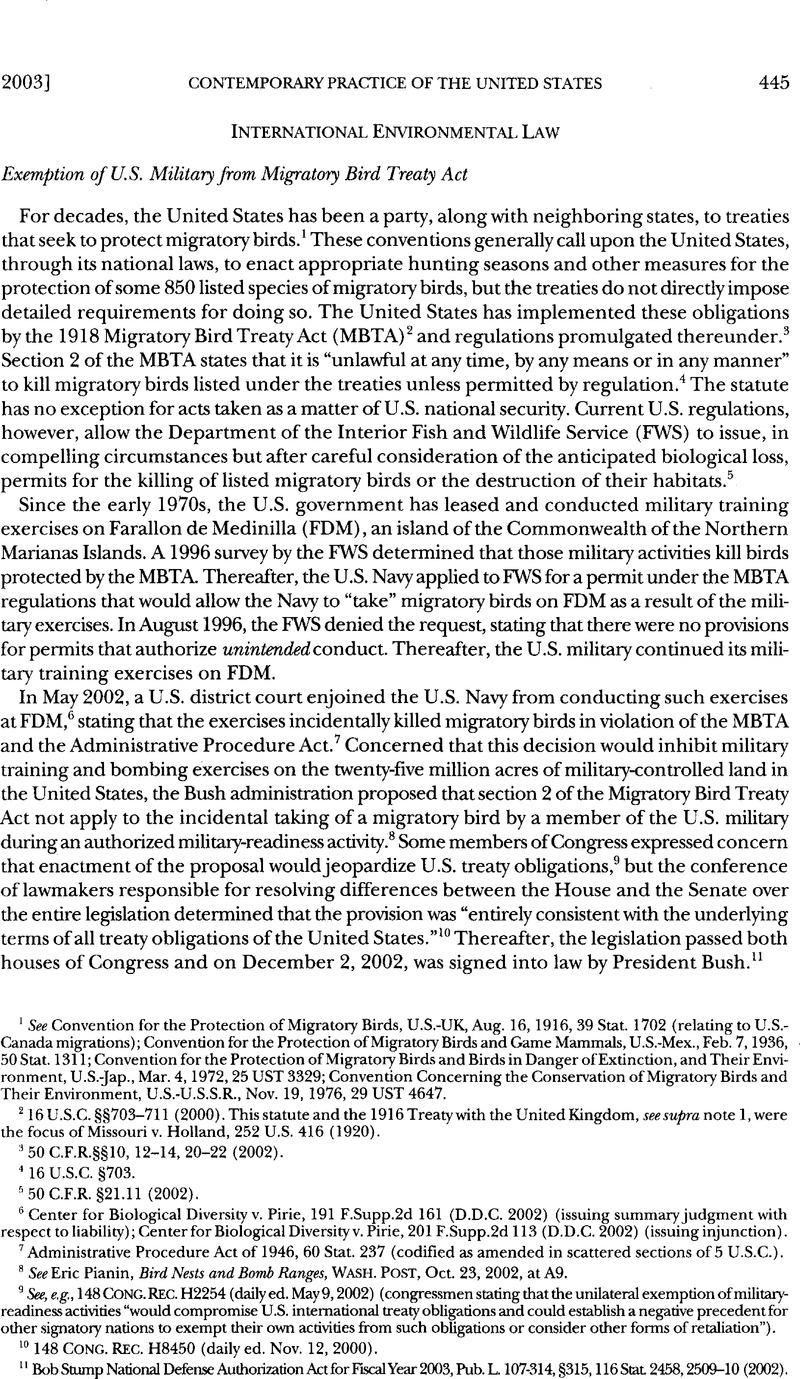

1 See Convention for the Protection of Migratory Birds, U.S.-UK, Aug. 16, 1916, 39 Google Scholar Stat. 1702 (relating to U.S.Canada migrations); Convention for the Protection of Migratory Birds and Game Mammals, U.S.-Mex., Feb. 7, 1936, 50 Google Scholar Stat. 1311; Convention for the Protection of Migratory Birds and Birds in Danger of Extinction, and Their Environment, U.S.-Jap., Mar. 4, 1972, 25 Google Scholar UST 3329; Convention Concerning the Conservation of Migratory Birds and Their Environment, U.S.-U.S.S.R., Nov. 19, 1976, 29 Google Scholar UST 4647.

2 16 U.S.C. §§703–711 (2000). This statute and the 1916 Treaty with the United Kingdom, see supra note 1, were the focus of Missouri v. Holland, 252 U.S. 416 (1920).

3 50 C.F.R.§§10, 12–14, 20–22 (2002).

4 16 U.S.C. §703.

5 50 C.F.R. §21.11 (2002).

6 Center for Biological Diversity v. Pirie, 191 F.Supp.2d 161 (D.D.C. 2002) (issuing summary judgment with respect to liability); Center for Biological Diversity v. Pirie, 201 F.Supp.2d 113 (D.D.C. 2002) (issuing injunction).

7 Administrative Procedure Act of 1946, 60 Stat. 237 (codified as amended in scattered sections of 5 U.S.C.).

8 See Pianin, Eric, Bird Nests and Bomb Ranges, Wash. Post, Oct. 23, 2002, at A9 Google Scholar.

9 See, e.g., 148 Cong. Rec. H2254 (daily ed. May 9, 2002) (congressmen stating that the unilateral exemption of military readiness activities “would compromise U.S. international treaty obligations and could establish a negative precedent for other signatory nations to exempt their own activities from such obligations or consider other forms of retaliation”).

10 148 Cong. Rec. H8450 (daily ed. Nov. 12, 2000).

11 Bob Stump National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2003, Pub. L. 107–314, §315, 116 Stat 2458, 2509–10 (2002).