The YouTube channel Ghost Town Living was started on April 13, 2020, by Brent Underwood to record his daily life, exploration, and reconstruction of the old mining town of Cerro Gordo in California (Figure 1). Prior to this undertaking, Underwood was an investment banker, a partner at a marketing firm, and the founder of a hostel. The success of the channel has also, over time, generated some revenue toward its reconstruction and provided advertising for fundraising ventures (Brier and Friends of Cerro Gordo Reference Brier2020). As of December 2021, the channel had 1.39 million subscribers with 57 videos posted. In September 2021, a secondary channel, Ghost Town Two, was started, which hosts shorter, less formatted content. The main channel hosts videos ranging in length from 10 minutes to over an hour, with weekly releases when possible.

Figure 1. Screenshot of the home page of Ghost Town Living (https://www.youtube.com/c/GhostTownLiving, captured January 2022).

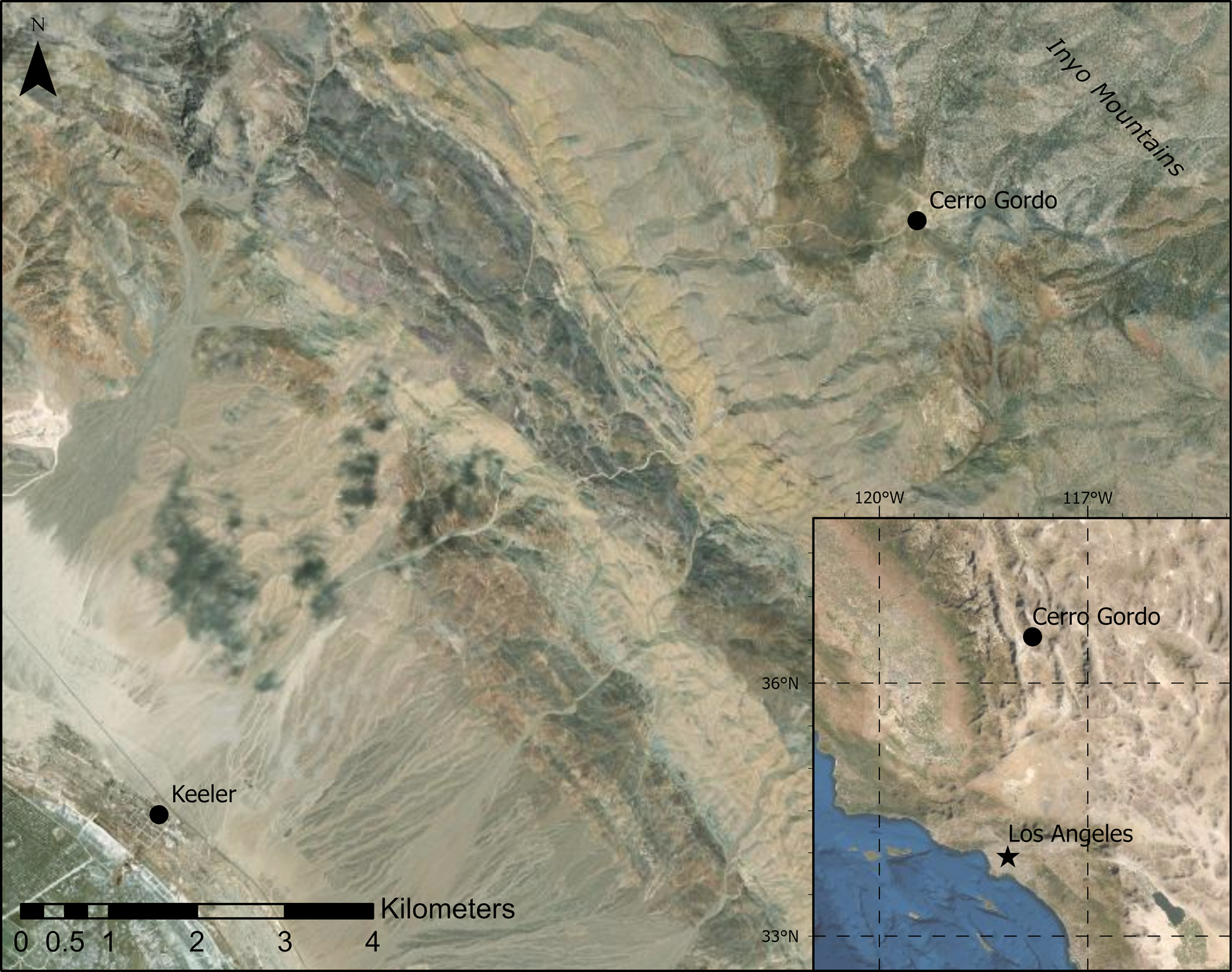

The town of Cerro Gordo is located in the Inyo Mountains, Inyo County, California, and is reached via the nearby town of Keeler (Figure 2). Cerro Gordo was actively mined from 1866 to 1938, and it primarily produced first silver and then zinc, among other materials in smaller quantities. By the 1940s, only a few families remained at Cerro Gordo, and the largely abandoned town was left to the care of Wally Wilson. Wilson sold artifacts from the town and parts of the buildings themselves as a way to try to make a living (Underwood Reference Underwood2020a). The town passed between owners until, in 1973, Jody Patterson purchased a 25% stake in the town from her uncle, the then owner. She would eventually purchase the whole town because of her affinity with it, but she passed away in 2001. Prior to the purchase by Underwood, the town was under the care of Robert Louis Desmarais, who still features in some of the videos (Park Reference Park2019; Underwood Reference Underwood2022).

Figure 2. The Location of Cerro Gordo in California, USA. (Satellite imagery: Earthstar Geographics, Maxar.)

Underwood and his partner Jon Bier, together with investors, purchased Cerro Gordo and 136 ha of the surrounding area in 2018 for $1.4 million with the goal of turning it into a tourist attraction while maintaining the character of the town (Figure 3). This endeavor involves the restoration of the extant buildings, reconstruction of destroyed buildings, and the creation of new ones in the town, all for stays by future visitors. The YouTube channel is a means to document the process, and it arguably owes some of its success to the COVID-19 pandemic, given that Underwood moved to the town to live alone in isolation. This led to news articles with titles such as “Abandoned Ghost Town's Owner Stuck There for More Than a Year” (Laharia Reference Laharia2021), among others (Jackson Reference Jackson2021), which have fueled interest in the channel and the town. Whereas the definition of “ghost town” refers to towns that have been largely abandoned, usually with some of their structures left intact (Merriam-Webster Dictionary 2022), the idea of “ghosts” in a ghost town is one that also draws people's interest, and it has even been featured in a few videos (Underwood Reference Underwood2020b, Reference Underwood2020c, Reference Underwood2021a). In any case, phrases such as “I've been living in a ghost town” and “alone in a ghost town” often feature in the video titles, and they serve as good marketing.

Figure 3. The ghost town of Cerro Gordo. (Screenshot from Underwood Reference Underwood2020a at minute 2:42.)

The channel is made for entertainment, but from a heritage and archaeological standpoint, it raises some considerations that are worth articulation and discussion. The town of Cerro Gordo, although in private hands, is part of the mining history of California, as are other towns such as Bodie, which has recently had public involvement as part of a “Citizen Preservationist” approach (Lercari and Jaffke Reference Lercari and Jaffke2020). The extant buildings in the town are relatively well preserved due to the fact that the previous owners not only ran tours of the town and its buildings but maintained them. Underwood's (Reference Underwood2020a) aspirations for the town are to preserve its “history” and fiscally develop it for tourism. Watching the videos, it becomes clear that while exploring the mines and town of Cerro Gordo, Underwood is conserving not just the history but also the process of doing so by actually recording what he is finding and doing. It is how it is done in addition to what that is interesting from an archaeological standpoint as the mining town is transfigured into something that resembles the original town but with a fundamentally different function.

RECORDING AND RECONSTRUCTING CERRO GORDO

Frequently in videos, Underwood (Reference Underwood2021b, Reference Underwood2021c) will restore or reconstruct old mining cabins, either for potential future guests or as part of his exploration of the wider landscape (Figure 4). These reconstructions use existing foundations, or they are just on the site of an old cabin. To build them, materials are scavenged from the original structures or others nearby. Underwood (Reference Underwood2021d) has also collected material from another mining town—Darwin, California (about 35 km south–southeast)—deconstructing buildings that were scheduled for destruction due to future mining prospects in the area and using the wood in new constructions at Cerro Gordo. After a year of work, he has already exhausted much of what could be scavenged from Cerro Gordo (reused wood saves money, given currently increasing costs for new wood). Interestingly, the deconstructed buildings from Darwin contained materials that originated from another (unnamed) mining town, further deepening the heritage of the materials. Underwood (Reference Underwood2021d) records which materials were used in the construction of each building and from where they came. The reconstruction of the buildings from “original” materials forms an amalgamation of mining history, the process of which would otherwise be lost if not for the recording undertaken in the physical and digital notes kept by Underwood, and the videos. The extent of this recording is not specified. However, it is likely to only generally indicate which materials came from where and not reach the level of the provenience of individual planks.

Figure 4. Underwood rebuilding a cabin. (Screenshot from Underwood Reference Underwood2021b at minute 22:29.)

One of the centerpieces of the town was to be the refurbishment of the American Hotel, which originally opened on June 15, 1871. Unfortunately, the structure burned down due to an electrical fire on June 15, 2020 (Underwood Reference Underwood2020d). Construction has since begun on a replica (Underwood Reference Underwood2020e, Reference Underwood2021e). It is as yet unclear how much of the new structure will be composed of building materials scavenged from old mine buildings, but it will follow the “original plans and blueprints . . . up to modern code” (Brier and Friends of Cerro Gordo Reference Brier2020). In any case, the construction of the new hotel in the same place as the old one is another example of the transfiguration of the town. The function of the new hotel will still be a hotel, as it was in 1871. Now, however, it is to support tourists who are viewing an inactive mining town, not miners.

Archaeologists will likely cringe at some of the methods used in the videos, which have included metal detectors, mechanical diggers, and dynamite (Underwood Reference Underwood2020f, Reference Underwood2021e, Reference Underwood2021f). Frequently in the videos, Underwood attempts to find new access routes into the Union Mine, the main and largest mine in the town. Potential shafts are identified, and if they cannot be dug out by hand, in a few cases, a mechanical digger opens them further by removing the rock above the shaft. In one case, even dynamite was used to gain access to the collapsed shaft of a mine (Underwood Reference Underwood2020f). Although the resultant videos have a “wow” factor that suits the YouTube medium, one can question whether these methods were strictly necessary.

Underwood frequently partners with friends and volunteers in his work at the town. One video features a collaboration with detectorists who were invited to scour the landscape for artifacts (Underwood Reference Underwood2021f). The objects found were then left at the town and placed in the Cerro Gordo Museum (previously the General Store), as are any other objects found by Underwood. Another video features Underwood excavating the dump under the icehouse of the American Hotel site (after its destruction) looking for artifacts and bottles, with little consideration for contextual preservation (Underwood Reference Underwood2020g; compare, of course, the efforts of professional archaeologists, such as Petrosyan et al. Reference Petrosyan, Azizbekyan, Gasparyan, Dan, Bobokhyan and Amiryan2021). This also holds true for objects found in the mines, which are picked up and moved without proper assessment or documentation (except for the videos themselves). Despite this, and the underlying tourism angle of the endeavor, Underwood genuinely seems to care about what he is doing. This sentiment certainly comes through in the videos, where an earnest Underwood addresses the camera and muses on the stories of the people who once lived at the town (e.g., Underwood Reference Underwood2021g).

Perhaps one of the most valuable contributions to documenting the history of the town are the videos themselves. Underwood records not only where things were found but also what their current condition is, as well as other features such as dynamite stores and graffiti. In addition, not all footage that is recorded is used in the videos, creating an extensive (if private) record of the material remains in the area. This record in video form, although perhaps not a thorough survey of the mines (archaeological or otherwise), still presents a form of cataloging that would otherwise not likely be done, given the lack of resources among professional archaeological services. Should anyone wish to assess the current state of the mines, or even map certain areas, the videos may serve as a sufficient source of data. However, much of what is being done is irreversible (as is the case with much archaeological practice), and the provenience recording by an amateur is admirable but not at professional standards.

DISCUSSION

Underwood is not an archaeologist, but his videos have engaged the public in his work and the heritage of Cerro Gordo. Archaeology can be viewed by nonarchaeologists and amateurs as an esoteric field, and often professional archaeologists are seen as “by the book” individuals who will not step out of their disciplinary norms. Working with private individuals and collections is still treated with skepticism by some in the discipline, and in some cases, such distrust is justified given that objects can be from dubious origins. However, as others have suggested (e.g., Douglass et al. Reference Douglass, Kuhnel, Magnani, Hittner, Chodoronek and Porter2017; Shott Reference Shott2014; Wright Reference Wright2021), it is through such collaborations with private individuals that archaeology will be able to increase its exposure to the public in an accessible way. Indeed, failure to engage with private materials can have negative consequences for public perception of archaeology and the interpretations of artifacts/areas (Wilson Reference Wilson2012). Open dissemination of accessible information is therefore one of the ways that archaeologists can and do interact with the public, such as through podcasts (e.g., Slotten Reference Slotten2021). Watching the videos, it is easy to imagine destinations like Cerro Gordo welcoming visitors using new technologies such as augmented reality or apps that encourage preservation (Douglass et al. Reference Douglass, Day, Brunette, Bleed and Scott2019; Lercari and Jaffke Reference Lercari and Jaffke2020; Liang Reference Liang2021).

YouTube and video web pages like it are now a prominent way for disseminating knowledge, given that they are largely free and accessible to increasing numbers of people. A brief search of YouTube will bring up a number of channels by “amateurs”—that is, those who hunt for artifacts to sell for profit (fossickers) and detectorists. Most of what many would consider “archaeologist” content is restricted to documentaries, tutorials or lectures, and features by research projects, although there are certainly exceptions to this, such as Archaeosoup (Barkman-Astles Reference Barkman-Astles, Williams, Pudney and Ezzeldin2019). YouTube certainly also contributes to the spread of misinformation—pseudoarchaeology is given a platform that is mixed with factual content.

With this said, given the increasing threat of modern activity to historic sites around the world, should the enthusiasm of amateurs not be encouraged and potentially utilized? As stated elsewhere (Richardson and Dixon Reference Richardson and Dixon2017), amateur involvement has always formed a part of heritage and archaeology inquiry. The appropriateness of collaboration (or the involvement of amateurs at all) is of course contextually dependent (e.g., Thomas Reference Thomas2015). In the case of Cerro Gordo, it is privately owned land that lacks protected status that would prevent modification or alteration. However, future work at Cerro Gordo could benefit from the input of a trained archaeologist—someone familiar with conservation, archiving, recording, and general excavation—or perhaps even a collaborative research project (for a discussion on how archaeologists can engage with those who work in public edutainment, see Snyder Reference Snyder2022). Archaeologists do not need to take over, but they can provide more recommendation and guidance, at least in cases such as Cerro Gordo (cf. Wright Reference Wright2021).

We can perhaps evaluate the work of Underwood and the volunteers who help him for their contributions, because they focus on a single project for longer than many archaeologists are ever able to commit to or fund. This long-term interest by individuals such as Underwood—perhaps advised by archaeologists, historians, and conservators—can do more for the public image of archaeology than archaeologists themselves can, in what may be a mutually beneficial relationship. What this collaboration would or could look like would perhaps be akin to the show Time Team, where excavations were undertaken rapidly to suit the episodic format (Bonacchi Reference Bonacchi2013). Although similar, such a venture could likely be done over a period longer than three days, which would better suit the archaeological process, and could therefore still be featured in one or more videos for the YouTube channel. At Cerro Gordo, the reconstruction of a ghost town's buildings in new forms with old materials helps it retain its historic “character” while also transfiguring it for a new overall function that will help to further preserve it in the future. The mining history of the area goes back to 1866, and although Cerro Gordo is considered “historic,” it is not necessarily protected by legislation, and Underwood has almost free reign to modify the buildings however he likes. That the land was once the home of Native American tribes is mentioned in passing in a few of the videos, but it has yet to be addressed or featured in any substantive way.

While watching the videos, Underwood's earnest enthusiasm is evident, but ultimately, monetary gain is the aim of the endeavor as well as the preservation of its history. Perhaps a cynical observer would note that the town must be self-sustaining if it is to thrive, and YouTube is a source of income that helps to achieve that through both awareness and revenue from ads. Enthusiasm is not necessarily “best practice” from an archaeological standpoint, but Underwood is not trying to do archaeology, and he has no obligation to do so. But what if that enthusiasm could be channeled with a few recommendations from, collaborations with, or guidance by an archaeologist? The documentation undertaken by Underwood as a private individual of both his reconstructions and the area itself is a curation of the history of the area, and by extension, of California's mining history. If done to a more professional standard, it would form a valuable resource for future research. It must be remembered that without the success of Ghost Town Living on YouTube, such recording may not have happened, and a part of the mining history of California might slowly be lost.