Book contents

Introduction

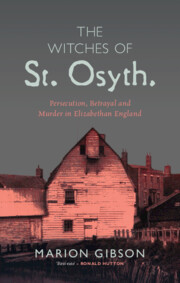

Welcome to St Osyth

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 02 December 2022

Summary

Introduces St Osyth, Essex: its history and landscape, and explains the context and setting of the witchcraft accusations of 1582.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Witches of St Osyth , pp. 1 - 9Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2022