Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Frederick Douglass and the Philosophy of Slavery

- 2 W. E. B. Du Bois and the Redemption of the Body

- 3 The Mephistophelean Skepticism of Stephen Crane

- 4 Charles Chesnutt: Nowhere to Turn

- 5 Richard Wright: Exile as Native Son

- 6 Peasant Dreams: Reading On the Road

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

4 - Charles Chesnutt: Nowhere to Turn

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 26 June 2019

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Frederick Douglass and the Philosophy of Slavery

- 2 W. E. B. Du Bois and the Redemption of the Body

- 3 The Mephistophelean Skepticism of Stephen Crane

- 4 Charles Chesnutt: Nowhere to Turn

- 5 Richard Wright: Exile as Native Son

- 6 Peasant Dreams: Reading On the Road

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

On March 14, 1862, Federal forces captured the inlet port city of New Bern, North Carolina, which they would hold through the rest of the Civil War. Slaves soon gathered behind Union lines; local white landholders fled; and a chaplain in one of the Massachusetts regiments occupying the city, a man named Horace James, undertook to organize the “contraband,” as the dislocated slaves were then called (as we saw in the foregoing chapter). He arranged for them to settle along the Trent River on plots of abandoned land. To honor their benefactor, the now-freed slaves named their settlement James City. The freedmen prospered and, according to James, by 1865 most of them had laid up considerable property, in the form of livestock, carts, and the like, and a number had succeeded as merchants. And there they lived for twenty-eight years until, in 1893, Governor Elias Carr dispatched a regiment of the First North Carolina Militia to evict the men and women of James City. Title to the land had long been in dispute in the courts—that is, until a decision was made, in 1891, to transfer the land to its antebellum owners so as to make enforceable certain deeds possessed by the white family who had, at the end of a long series of exchanges, most recently purchased the “bad paper”—as the merchants of debt now call it—from them (or rather, from their successors). In 1893, when the eviction orders were put into effect, the black men of James City had no choice but to sign three-year leases to work the land they had owned, or so they believed, for thirty years (quite as if they'd been victims of sub-prime mortgages and predatory lenders). They had nowhere to turn. They had had a taste of an America made real, but soon enough the “swarthy specter” of slavery took “its accustomed seat” at the nation's post-Reconstruction feast (Souls 366). America was again what Du Bois said it had always been: an “armed camp for [the intimidation of] black folks,” and for the abuse of their labor (Souls 436).

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

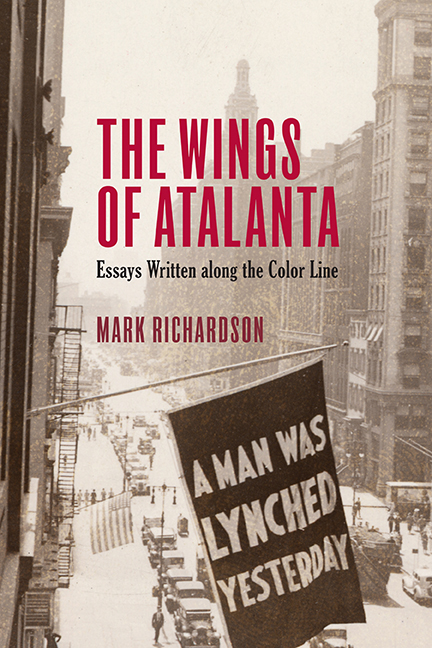

- The Wings of AtalantaEssays Written along the Color Line, pp. 164 - 203Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2019