From its revolutionary roots to more recent reforms, China’s modern political system has prompted lively debates about regime durability. In the wake of the Soviet Union’s collapse, attention turned to the possibility of the demise of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), driven by factors such as uncontrollable centrifugal pressures, demographic change, and institutional decay.Footnote 1 The party’s dominance in the nearly three decades since the fall of other communist party-led regimes around the world, while defying some predictions, indicates that party institutions created for revolutionary purposes can negotiate key transitions. These transitions include responding to the ruling party’s current agenda of administrative reform and modernization. Understanding these shifts and the party’s durability over time necessitates an examination of the institutional underpinnings of this rising global power.

Institutions have often been the object of inquiry in the study of authoritarian systems. Designing, constructing, and maintaining institutions of governance are vital to the state-building process, if not synonymous with it. Political institutions that constrain elected officials in democracies are often established in autocratic contexts to serve the dictator’s (or leaders’) bid to stay in power. Such institutions facilitate the ordering of state and society and extend the coercive capacity of the ruler, and they do so across time and space. That institutions in authoritarian regimes often possess a complexity on par with their democratic counterparts is not surprising, but the purposes of these nondemocratic institutions are at all times conditioned by the political context of which they are a part, that is, to sustain authoritarian rule. Given this core assumption, the task lies in discerning the functions served by a particular authoritarian institution and its impact on the individuals who guide and are guided by it. An additional undertaking lies in evaluating an institution’s capacity for coping with the uncertainty, unforeseeable circumstances, and contingencies that all rulers in power must eventually confront. These matters of institutional design and adaptiveness are complicated by the “sunk costs” that accompany the creation of any institution, by the displacement of systemic missions with more local, organization-specific objectives, and also by tradition and the inertia that may resist pressures for change.

Elections, legislatures, and parties are among the most prominent and well-studied examples of political institutions adopted by authoritarian leaders.Footnote 2 The channels through which they contribute to regime survival are several: by co-opting potential opposition (Gandhi Reference Gandhi2008b; Gandhi and Przeworski Reference Gandhi and Przeworski2007; Lust-Okar Reference Lust-Okar2006), managing elites in opposition groups (Blaydes Reference Blaydes2008; Lust-Oker Reference Lust-Oker2005; Tezcur Reference Tezcur, Lust-Okar and Zerhouni2008), providing political information (Cox Reference Cox2009), and limiting economic predation by the autocrat (Gandhi Reference Gandhi2008a; Wright Reference Wright2008). More generally, institutions allow the dictator to make a credible commitment to sharing power with supporters (Magaloni Reference Magaloni2008). This solves a core dilemma facing all dictators. In order to remain in power, the dictator must rely on some base(s) of support, but these groups are unwilling to back a dictator who may, once in power, renege on promises. To generate confidence in his decision to extend benefits to those who provide loyal service, a dictator may create “power-sharing institutions” that over time generate some confidence in the dictator’s willingness to abide by nonarbitrary rules of the game.Footnote 3

Parties are instrumental in solving this credible commitment problem. They allow the dictator to make credible commitments to loyalists by promising access to locally generated revenues or future privileges in exchange for service in the present (Lazarev Reference Lazarev2005, Reference Lazarev2007). One mechanism for this is the allocation of party membership and positions; the privileges of party office present an intertemporal solution to the dictator’s commitment problem. This present-service-for-future-privileges arrangement has been tested empirically in the Soviet regime, where the party controlled all political, economic, and social mobility, but this monopoly is not a necessary condition for the arrangement to remain credible. As the Chinese case attests, the emergence of private entrepreneurs does not imply the end of high demand for party office.

Critically, parties lengthen the regime’s time horizon for survival. Because of this expectation of regime durability, parties structure intra-elite conflict by offering elites the promise of “medium and long-term gains despite immediate setbacks” (Brownlee Reference Brownlee2007: 12). A stable outcome may result as parties generate expectations that they will remain in power, which in turn promotes elites’ willingness to invest in development (Olson Reference Olson1993).Footnote 4

Single-party rule solves several additional problems of governance. Ruling parties, unlike collective leadership under military rule, generate strong incentives for party members to support the authoritarian status quo because these party members and cadres depend on the party for rents (Geddes Reference Geddes1999b).Footnote 5 Party members cannot “retreat to the barracks” as military leaders might. Even more, by dispersing authority over a broader political base, parties provide a counterbalance to the threat of military coup (Geddes Reference Geddes2008). Parties also engineer outcomes with a “tragic brilliance”: the general population may accept corruption and suboptimal policies because of the party’s ability to maintain widespread patronage networks (Diaz-Cayeros et al. Reference Diaz-Cayeros, Magaloni and Weingast2003). In China, the narrower extension of party patronage to economic elites forges the credibility that encourages private investment (Gehlbach and Keefer Reference Gehlbach and Keefer2008).

While those who invest resources in creating ruling parties are engaging in several trade-offs – dispersing authority, investing resources in party organization rather than repression, and so on – this institutional choice ultimately enhances the durability of the regime. Forming a ruling party appears to be a successful strategy: in the post–World War II period, authoritarian regimes led by a single party have enjoyed long durations of rule in comparison to authoritarian counterparts without a ruling party.Footnote 6 Among the institutions that a dictator may choose to establish or maintain, ruling parties are perhaps the most critical for understanding questions of authoritarian resilience.

While acknowledging that parties serve these important functions of elite management and mass mobilization, this book focuses on problems of party organization, particularly the organizations located within a ruling party and the individuals who guide those organizations.Footnote 7 In much of the existing literature, there is less emphasis on drilling down into the party itself and asking questions of party structure, the consequences of organizational design, and how these lay the foundations for stable single-party rule. Rather than treating parties as monolithic institutions, this study maps a more interior terrain. Its point of departure and focus is on variation in intraparty organization. This requires a look at the organization – and organizational problems – of perhaps the most highly structured of single-party regimes, those led by Leninist parties.

Inside Lenin’s “organizational weapon”

Because of their emphasis on organization and hierarchy, Leninist party systems present an ideal case for probing the purposes, risks, and advantages of particular decisions in party-building. The revolutionary, and eventually totalitarian, aspirations that motivated the creation of these parties translated in practice to party organization that would facilitate the complete control of state and society.Footnote 8 Lenin’s original conception for the party was of an organization led by “professional revolutionaries” who were promoted from within the “rank and file” membership.Footnote 9 He wrote that “the only serious organizational principle for the active workers of our movement should be the strictest secrecy, the strictest selection of members, and the training of professional revolutionaries.”Footnote 10 In contradiction to egalitarian ideological commitments, the party would be “an organization which of necessity is centralized” and governed by hierarchy.Footnote 11 The bureaucratic centralism that Lenin’s party eventually embraced was done unapologetically (Wolfe Reference Wolfe1984: 24–6, 192–95).Footnote 12 The Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) became the organizational embodiment of the pragmatic recommendations bound up in Lenin’s political vision. The party was to coordinate political functions, distribute economic power, and play the crucial centralizing role in the command economy and politically closed system that endured for over 70 years (Klugman Reference Klugman1989). In theory, it was also to possess the organizational flexibility to respond to unforeseen circumstances and contingencies.

With the global diffusion of Leninist principles, these parties have become highly structured and complex organizations, including extensive functional differentiation of constituent parts.Footnote 13 A range of subparty organizations play a supporting role in the maintenance of the party’s political authority: propaganda bureaus, party personnel departments, courts, unions and other mass organizations, party schools, and the like. The central committee of a ruling communist party becomes the principal to these various organizational agents, and this relationship is mirrored at lower administrative levels in the system, forming overlapping chains of principal–agent relationships. This parallels the principal–agent relationship between higher-level cadres and their subordinates, for example, the principal role played by a city party committee over agents in a county or township located within the city’s jurisdiction. The pervasiveness of these hierarchical relationships within the political system, at both the individual and organizational levels, provides the structural basis for governance and the distribution of political power.

Leninist systems are characterized by a critical relationship that is often overlooked in general studies of parties in autocracies: party management of the state bureaucracy. Party organization, specifically party integration with and dominance over the bureaucracy, constitutes a source of political power (Barnett and Vogel Reference Barnett and Vogel1967; Selznick Reference Selznick1960). As the most prominent example of an extant ruling party formally organized along Leninist lines, the CCP maintains and reinforces its organization through party penetration of the state.Footnote 14 While there have been attempts to draw an analytical and empirical line between the party and state in China (Zheng Reference Zheng1997), in practice the two political bodies remain intertwined.Footnote 15 Existing work on the Chinese case characterizes the relationship as suffused with bargaining and negotiation (Lampton Reference Lampton1987, Reference Lampton, Lieberthal and Lampton1992; Naughton Reference Naughton, Lieberthal and Lampton1992); a reflection of elite conflicts (Dittmer Reference Dittmer1978); and, above all, distinguished by party domination and coordination (Harding Reference Harding1981; Li Reference Li1994; Schurmann Reference Schurmann1970). In this sense, the state bureaucracy in China is not a “neutral layer” between the ruling party and the governed but rather an instrument in the service of political power holders (Massey Reference Massey1993).

At the individual-level foundations of this arrangement, who becomes a cadre, or bureaucrat of the party and/or state apparatus, is of fundamental and paramount importance. Since “the formation of cadres is a basic task of communist organization” (Selznick Reference Selznick1960: 19), it becomes vital for party authorities to manage who may enter and move up the ranks. In this sense, the party presents an organizational means to solve a political selection problem. This function is both separate from and part of the elite bargaining function noted previously. The party is an organized means for selecting those who are most likely to advance party goals. In the case of China, it is in the interest of CCP authorities to devise effective instruments for controlling bureaucrats and party organs at various levels of administration because disciplined party agents are more likely to implement party policies. More simply put, “Leading cadres are at the head of the reform train [in China]. We must develop these leaders, otherwise reforms will be fruitless.”Footnote 16 In light of the critical role played by those institutions that control who joins the party elite, this book will focus on party strategies of both bureaucratic management and political control.

Controlling China’s political elite

Through interlocking but functionally specific bureaucratic organizations, a Leninist ruling party attempts to control several overlapping groups of key political actors: party members, rank-and-file party and government cadres, and senior (leading) party and government cadres. Who is a member of the political elite in China? Scholars have identified this population in general by employing a variety of criteria, beginning with the vague parameter of those in possession of “decisive” political power (Smith Reference Smith1979: Appendix A) or those who enjoy “exclusivity, superiority, and domination” (Farmer Reference Farmer1992: 2). This is consistent with Putnam’s (Reference Putnam1976) emphasis on those who “influenc[e] the policies and activities of the state, or (in the language of systems theory) the … authoritative allocation of values” (p. 6). These definitions, which have the advantage of comparative application, are difficult in practice to apply defensibly to particular cases. Drawing from Mills’ (Reference Mills1959) precedent, in which the “power elite” are those in positions of authority, this study employs a positional approach to defining the political elite in China. Those members of the party and state bureaucracy who have attained some “leading” rank at the level of vice-county magistrate or equivalent are considered members of the political elite within China.Footnote 17 Attaining such rank often requires marching up the grassroots ranks of the party bureaucracy or civil service. The disadvantage of this approach is its emphasis on formal title, as opposed to informal bases of power, which may overlook to some degree the increasing diversity in Chinese society, where entrepreneurial talent, global connections, and political authority may be interconnected but separate bases of political influence.

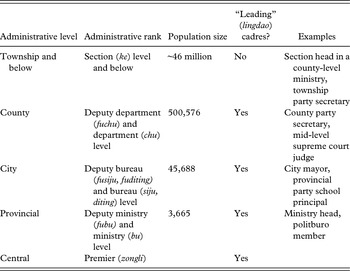

In a Leninist system, cadres are responsible for party and government work at various administrative levels and across functional areas of specialization. This population of party and government managers is then divided into increasingly smaller and exclusive ranks, at one time up to 25 ranks in the Peoples’ Republic of China’s (PRC).Footnote 18 “The CCP referred to its functionaries by the generic term ‘cadre’ (ganbu), regardless of whether they worked for the party, the Government or the army. In this usage, cadre referred to those who had a certain level of education (initially secondary school level), who had some specialist ability, and who carried out ‘mental’ rather than ‘manual’ labor” (Burns and Bowornwathana Reference Burns and Bowornwathana2001: 23).Footnote 19 More bluntly, a cadre is anyone who “eats the state’s grain” (chi guojia liang shi).Footnote 20 At present, the Chinese bureaucracy, in all its organizational variety, comprises over 40 million individuals.Footnote 21 Table 1.1 offers a sketch of the size of the entire bureaucratic system and levels within the system.

Table 1.1 The organization of public officials in China, 1998

| Administrative level | Administrative rank | Population size | “Leading” (lingdao) cadres? | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Township and below | Section (ke) level and below | ~46 million | No | Section head in a county-level ministry, township party secretary |

| County | Deputy department (fuchu) and department (chu) level | 500,576 | Yes | County party secretary, mid-level supreme court judge |

| City | Deputy bureau (fusiju, fuditing) and bureau (siju, diting) level | 45,688 | Yes | City mayor, provincial party school principal |

| Provincial | Deputy ministry (fubu) and ministry (bu) level | 3,665 | Yes | Ministry head, politburo member |

| Central | Premier (zongli) | Yes |

At the very top of this hierarchically organized system is a stratum of individuals whose appointments are managed by the Central Committee of the CCP.Footnote 22 A slightly larger population of “leading cadres” (lingdao ganbu) possesses local policymaking and allocation authority for the party and state. Leading cadres maintain the party’s political dominance and the state’s administrative authority. This leading cadre class produces the policies that the rest of the bureaucracy must implement (Burns Reference Burns and Burns1989a, Reference Burns, Brodsgaard and Yongnian2006). In 1998, leading cadres totaled 549,929 individuals (Central Organization Department 1999). In other words, the more than 45 million public officials in China must be sifted through to produce an elite decision-making corps of fewer than 1 million.

Controlling promotion to and within this latter group, the senior cadre ranks, is a crucial arena for the party’s maintenance of “organizational health” (Nee and Lian Reference Nee and Lian1994). This is especially critical in a system as decentralized as China’s (Landry Reference Landry2003). Inability of higher-level authorities to manage party and government reformers is tantamount to a loss of party authority. The collapse of the Soviet Union reinforced for Chinese party authorities the danger in, among other things, a decline in party discipline (Shambaugh Reference Shambaugh2008a, Reference Shambaugh and Li2008b; Wang Reference Wang, Yu and Yang2002; Xiao Reference Xiao, Yu and Yang2002). Elite personnel decisions are a paramount responsibility of the party (Naughton and Yang Reference Naughton and Yang2004). Complicating this, authority relations between party managers and their subordinates are dynamic. While these relationships are moderated by the institutions that authorities use to monitor and control subordinates and the flow of information between levels, they are subject to the dictates of new generations of leaders and system-wide shocks – such as the transition to a market economy, technological change, new global balances of power, and shifting international alliances.

Placing China in context: high growth, low bureaucratic exit

While the tasks of political elite selection and party organization must be confronted in all single-party authoritarian regimes, the CCP faced particular circumstances and challenges at the onset of reforms in the late 1970s, as the Chinese state was “growing out of the plan” (Naughton Reference Naughton2007: 92–3). Comparatively low bureaucratic turnover during the post-Mao economic transition, which commenced in 1978, generated pressures for internal updating of cadre administrative skills. Party leaders, beginning with Deng Xiaoping, realized the need to engineer a bureaucratic transformation to meet the demands of a market transition, but political constraints made a purging of party managers unfeasible. The legitimacy wielded by the old revolutionary cadre generation limited the range of alternatives. At the same time, the demands of an assertive economic modernization program were straining the human resources of a political system designed to manage a command economy.

With the implementation of liberalizing economic and social reforms under Deng, the party faced a problem: Chinese leaders realized that the party comprised a high number of public managers with outdated and irrelevant skills. There existed a cadre class that suffered from “one high and two lows” – bureaucrats were, on average, too old (i.e., their age was too high) while their education and professional skills were insufficient (Lee Reference Lee1983: 676). Hence, the rallying cry was to develop a “revolutionary, younger, better educated, and more technically specialized” (geminghua, nianqinghua, zhishihua, zhuanyehua) cadre corps.Footnote 23

This bureaucratic transformation was to take place in the context of unprecedented economic development. With the initiation of reforms in 1978, China’s economy underwent dramatic change in terms of growth and industrial development. Official annual growth rates averaged 9.98 percent for the period 1978 to 2011.Footnote 24 Industrialization also took off in urban special economic zones and through “local state corporatist” strategies in the countryside (Liao et al. Reference Liao, Pan and Zeng1999; Oi Reference Oi1992, Reference Oi, Vermeer, Pieke and Chong1998a). The economic miracle presented by contemporary China has a seemingly incongruous basis in a single-party authoritarian regime, which begs further examination of how the ruling CCP has maintained organizational discipline during this period of rapid and apparently successful economic liberalization.Footnote 25

One way to place the Chinese case in its comparative context is to contrast the problem of low administrative turnover in China with the transformations taking place in other communist party states such as the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc countries of Central and Eastern Europe. This is an imperfect comparison due to the simultaneous political and economic transitions that took place in Western communist party states, but in all cases bureaucratic transformation was a requirement for successful economic reforms. In each country, engineering a revolution in bureaucratic talent was also complicated by the lure of new market opportunities. With their totalizing emphasis on party control over all political, economic, and social activities, Leninist party-led systems traditionally rely on monopsonistic control by the party over labor markets.Footnote 26 Over the course of market reforms, skilled labor that was formerly dependent on state entities for upward mobility found new options in newly created non-state sectors. When compounded with political reforms and, ultimately, revolutions such as those in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, there was considerable turnover in the bureaucratic ranks. This is observed in the data from a survey of postcommunist countries taken in the early 1990s: bureaucratic turnover ranged from a low of approximately 25 percent in Russia to 51 percent in the Czech Republic during 1988–93.Footnote 27

China, in comparison, realized much lower rates of bureaucratic turnover during its reform period despite the option for cadres with managerial experience or connections to “jump into the sea” (xia hai) of capitalism. Occupational change among cadres from 1988 to 1993 was much lower when compared to their transitioning European and Russian counterparts. In one representative national survey, only 7.3 percent of Chinese bureaucrats left the party or government ranks during that five-year period.Footnote 28 From the onset of reforms in 1978, bureaucratic turnover is not much higher. Only 15.8 percent of survey respondents reported leaving their party and/or state posts by 1993. Even as the CCP withdrew from its monopoly on economic opportunity, exit by bureaucrats to the private sector was rare. Turnover from 1978 to 1993 was due almost entirely to retirement; only one cadre reported joining the private sector during the period between 1978 and 1993.Footnote 29 These patterns may be explained by the particular incentives in place for cadres to stay in the system and realize benefits from profit-sharing contracts with party authorities and/or party-sanctioned extrabudgetary revenues (Ang Reference Ang2009; Solnick Reference Solnick1998: Chapter 7). There also exists the possibility that individuals retained their official office while “moonlighting” in private ventures. Such high retention rates may bode well as an indicator of party legitimacy, but this low turnover pattern has left party leaders with the problem of how to retrain China’s administrative class to cope with the implementation and management of economic and social reforms.Footnote 30

How has the party adjusted its organizations of bureaucratic control and management to account for building a new political elite? In a Leninist system in particular, party organizations designed for a command economy and ideologically disciplined cadre corps would seem outdated and out of place in a decentralized market economy, one with increased autonomy for decision-makers. The organizational puzzle posed by the case of the CCP is the persistence of seemingly anachronistic party organizations in the post-Mao period. Organizations forged during and for a revolutionary context have limited purchase in the management of a state no longer bent on revolution but rather focused on routine. Scholars have unpacked the many reforms contributing to the “remaking of China’s leviathan” and focused in particular on reforms of the administrative state.Footnote 31

The remaking of political bodies within the party has occurred more slowly than this administrative transformation, and deeper political reforms have lagged behind state reforms in China’s push to modernize its economy. Changes have proceeded slowly and cautiously, but it has been impossible for the party to ignore the pressures to adjust. The old standbys, Marxist-Leninist tenets and Mao’s writings, would not be enough to guide cadres’ administrative decisions in a market economy characterized by expanding trade, new forms of industrial production, and increasing global exchange. “For managers, entire careers spent learning how to maneuver through the planning bureaucracy to obtain scarce materials, to lower plan targets, to lobby for an increased wage fund, and so on become irrelevant to success in a marketized context” (Hanson Reference Hanson1995: 312). The pivotal issue becomes how to retrain these bureaucrats, and the strategy adopted has implications for the political and administrative future of China’s party-state.

While the state education system could take on some of this burden of re-educating managers, regular universities and schools might not promote entirely “correct” ideas.Footnote 32 In a field interview with a provincial-level party school teacher, he declared, “Ideological training must be preserved. You can’t have liberal-minded (ziyou zhuyi) university teachers teaching cadres; this task can’t be divided.” To continue exerting party control over individual bureaucrats, it would seem logical for party officials to draw on existing organizational resources. CCP organizations forged during the early, underground days of party activism have persisted into the present and offer one solution to the question of how the bureaucracy shall be reformed into a politically appropriate but professionally competent “organizational weapon.” A key issue is how to reform these revolution-era organizations to match current needs. An examination of the CCP’s cadre training system reveals how the party has sought to retrain, manage, and select administrators during a period characterized by dramatic economic growth, low exit from the cadre ranks, and the need for skilled public managers.

Party schools, party reform

Party schools are an understudied but critical component of the organizational life of communist party systems. These schools exist to “inculcate the desired attitude to the Party” on the part of new party recruits (Meyer Reference Meyer1961: 112). Crucially, they are responsible for the ideological training of revolutionary cadres.Footnote 33 Schools embody the party emphasis on discipline, correct thought and action, and organizational unity. They are sites for reinforcing individual commitment to the party.Footnote 34 In principle and to some degree in practice, party schools provide the organizational space for forging ideal cadres. Of importance is how schools carry out these functions and how they remain relevant in changing contexts.

In the case of China, party schools provide a well-situated case for examining how the party has generated incentives for party organizations to respond and adapt to the new demands of the post-Mao reform period. Numbering nearly 2,800 campuses nationwide, party schools constitute an extensive network of training academies for China’s political class (Appendix A). Party schools are the anchor within a larger category of organizations charged with cadre training.Footnote 35 The centrality of party schools within this organizational landscape is due to their exclusivity, since they have historically been sites for educating party members and officials.Footnote 36 These schools are a prime example of Leninist party organizations that would appear incompatible with a market economy and the changed domestic and global circumstances facing reforming China. Yet, reforms in cadre training have been one way to meet the demands imposed by economic change and modernization.

This study of party schools argues that by altering incentives while leaving Leninist party organization intact, the CCP has managed in the post-Mao period to induce organizational adaptation that has bridged, however incompletely, the disjuncture between new realities and prior institutional arrangements. As the following analysis of party schools will demonstrate, this adaptation is a result of a deliberate embrace of market mechanisms by central party authorities and the introduction of organizational competition, or redundancy, to the system.Footnote 37 Decades of reform have yielded more dynamic, relevant party schools. The process of marketization carries risks for party authorities, however. While party schools continue to serve critical roles in cadre education and promotion, incentives now exist at the organization level for party schools to embrace market opportunities, sometimes at the cost of party discipline.

Through case studies and extensive fieldwork, this book makes several contributions to the state of knowledge on political institutions in China. First, this investigation probes how party authorities have induced organizational change within the party school system and how this provides traction on the larger, multifaceted story of CCP survival in the reform period. This study builds upon the observation of many China scholars (e.g., Miller [Reference Miller and Li2008], Shambaugh [Reference Shambaugh2008a]) that the party has embarked on a broad-based institution-building project. Arguably, this has been in progress since the founding of the republic, but in its current form it is characterized by “interlocking patterns of neo-socialist marketization, bureaucratization and party building” (Pieke Reference Pieke2009: 18). My contribution is one of specifying mechanisms and processes: I unravel why we continue to observe significant investment in party schools in the reform period. In this narrative, I consider the logic underlying the decision to introduce market-based competition rather than apply bureaucratic reforms of a less radical nature. All of this is to lend a mesolevel, or institution-driven, view of how the party pursues its fundamental desire to not only survive through present reforms but remain their central architect.

Second, it demonstrates with survey data the mechanisms by which party schools contribute to the party’s management of human resources, in particular the exercise of party control over cadre careers. In so doing, it draws out assumptions that are implicit in existing studies to test whether party schools play a significant role in the construction of China’s political elite. Beyond the ideological import of these schools, this project maps out their function in the selection of cadres, specifically by measuring the effect of party school training on cadre promotion.

The third contribution of this study is to propose and assess specific indicators of organizational adaptiveness. The content of party school syllabi has shifted over time, and one question is whether to view these changes as adding to or detracting from processes of adaptive change. Through field visits and interviews conducted in the local party schools of provinces in the coastal and central regions of China, I present a ground-level understanding of change within the party. This allows for both a vertical and horizontal examination of how these party organs work, across regions and administrative levels. Such an empirical approach provides a more complete picture of the incentives, responses, and risks underlying political change in China.

Sources of adaptive capacity

Scholars of Chinese politics have examined various pathways to institutional change in reforming China, some of which are bottom-up in orientation and others which are elite-led. Informal institutions devised by local actors in response to state strictures can become the drivers of formal institutional change. This was the case with the blooming of grassroots capitalist activity in the reform period, compelling party officials to recognize and then co-opt capitalist practices within the party (Tsai Reference Tsai2006). This pathway of change is particularly striking due to the ability of local non-state actors to drive change upward and throughout China’s political and economic system. However, such change is precluded in arenas of political life which, short of reforms initiated within the party itself, are closed to non-party actors. Initial shifts in ideology, for example, are party-led. A second body of work has focused on the role of local experiments in stimulating systemic change (Heilmann Reference Heilmann2008a, Reference Heilmann2008b; Heilmann and Perry Reference Heilmann and Perry2011). Local experiments, which have roots in the party’s particular historical experience, are one means for authorities within the Chinese political system to assess new policy directions and reproduce those which have potential for nationwide implementation. This type of change also relies on grassroots action which higher authorities may choose to replicate as part of a larger national agenda. While policy experiments have affected a wide range of policy arenas and are intraparty in orientation, they are limited in their ability to move central political organs of the party. Third are studies of top-down, elite-led institutional change. These have traced the search by party leaders to avoid the mistakes of communist parties elsewhere (Shambaugh Reference Shambaugh2008a) and conceive of institutional change as an indicator of systemic rationalization and greater inclusiveness by the ruling party (O’Brien Reference O’Brien1990). Such studies offer detailed historically grounded analyses of change but do not embed the Chinese case in a broader comparative framework. The present study seeks to identify causal mechanisms with more general applicability.

In the post-Mao period, large-scale changes have tested the party’s flexibility and adaptiveness. The general problem to overcome is one of “trained incapacity”, where party functionaries reach a “state of affairs in which one’s abilities function as inadequacies or blind spots. Actions based upon training and skills which have been successfully applied in the past may result in inappropriate responses under changed conditions. An inadequate flexibility in the application of skills, will, in a changing milieu, result in more or less serious maladjustments” (Merton Reference Merton1968: 252). The antidote to the individual- and organizational-level dysfunction that Merton observed across bureaucracies is creating incentives for “adaptive efficiency,” that is, “an institutional structure that in the face of ubiquitous uncertainties … will flexibly try various alternatives to deal with novel problems that continue to emerge over time” (North Reference North2005: 154).Footnote 38

Such adaptiveness is distinct from and a subset of observed organizational change. While organizational change implies that some dimension of a unit is different in period t from period t+1 or t−1, adaptation speaks to the ability of an organization or a system to anticipate or respond to environmental change such that organizational changes achieved over time enhance that unit’s likelihood of surviving in a new time period. Adaptation, when it is either anticipatory or reactive, is not without risks. An organization, in the process of attempting to adapt to changes in its environment, may choose unwisely and inadvertently set in motion the conditions for its decline (Hall Reference Hall1976; Zammuto and Cameron Reference Zammuto, Cameron, Cummings and Staw1985). There is also a degree of uncertainty to environmental change such that an adaptive change made in response to one shift in the environment may lead to organizational maladjustment in the face of a different environmental context.

Of interest is how the CCP has generated adaptive solutions to novel challenges within existing party organization. Leninist parties such as the CCP have incorporated many features of a Weberian bureaucracy. Such a bureaucracy, indispensable to the modern state, draws on rules, offices, and expertise to govern bureaucratic behavior and administration. Organizational rationality derives from functional specialization across bureaucratic offices. Leninist parties comprise several of these features, notably the organization of party units according to the various needs bound up in the transformation of society and, ultimately, in the more mundane tasks of governance. Each core task of the party-state would have its own bureaucratic proxy, creating bureaucracies within the bureaucracy.

A central organizing principle of such systems is bureaucratic monopoly according to functional domain. While this lends coherence to the organization of the party-state and facilitates the assignment of both responsibility and blame, it is problematic from the standpoint of adaptability to change. A monopoly lacks strong incentives to innovate since there is inelastic demand for its output. In this sense, monopolies have a predisposition for “the quiet life,” and innovate rarely because they do not employ the same “diversity of processes” found in a competitive system (Niskanen Reference Niskanen1971: 161). Lenin’s institutional innovation on the Weberian bureaucracy, the creation of a hierarchical party system populated by “vanguard” revolutionary party members, and one that would guide society out of a capitalist-led state system, would seem an unlikely candidate to weather through significant changes such as system-wide economic transition. As the collapse of Leninist party systems in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union testify, the internal structure of these party-states proved incapable of withstanding the various stresses of party-led reforms and external change.

Organizational redundancy: replacing monopoly with partial competition

The CCP response to these institutional weaknesses has been to modify the Weberian and Leninist emphases on functional monopoly. With the onset of reforms, central party authorities have promoted interorganizational competition to cope with new economic and social uncertainties. This reflects the logic that the reliability of a system of imperfect, and hence fallible, parts may be increased through the introduction of competition or redundancy (Landau Reference Landau1969).Footnote 39 Redundancy, taken to the realm of governance and public administration, refers to the introduction of additional agencies to fulfill an organizational goal previously monopolized by a single agency.Footnote 40 It applies in all cases where agencies “make some contribution to the achievement of the system’s goal, but this contribution is blurred because some other element(s) make(s) a similar contribution” (Felsenthal Reference Felsenthal1980: 248). In this sense, redundancy is the introduction of slack, or additional resources, to a system (Landau Reference Landau1991). This slack then generates the reserve capacity that enables a system to become more tolerant of failure. Redundancy thus produces two important results: increased system reliability and incentives for organizational adaptation.

While reliability, or the mitigation of system failure, is the more widely researched benefit of redundancy (Streeter Reference Streeter1992), this study focuses on a second, but equally important outcome, that is, competition as a means to induce organizational change and adaptation to new circumstances. In their study of interservice rivalry in the US military, Enthoven and Rowen (Reference Enthoven and Rowen1959) argue that “human limitations being what they are, there is good reason to believe that a decentralized competitive system, in which people have incentives to propose alternatives, will usually meet this test [of developing comprehensive capabilities] more effectively than a highly centralized system” (p. 5). Competition increases the diversity of perspectives brought to bear on a particular issue, which increases the chances of discovering new alternatives. Because competition entails some ambiguity in the jurisdictional boundaries between bureaus, some blurring of organizational purpose, this “loosens structure” and “facilitates an expansion of the range of possible organizational responses to problems” (Lerner Reference Lerner1978: 20). One of the most powerful effects of the introduction of competition to a system is to stimulate change in preexisting actors.

The rationale behind the introduction of competition is to raise a system’s overall capacity to generate multiple alternatives for solving a problem. This is a logical response to the uncertainty that waxes and wanes in different political conditions. Furthermore, competition induces rival agencies to search more aggressively for alternatives. By increasing the number of agencies focused on a task, a greater number of possible alternatives are considered and pursued in the interest of fulfilling a system-wide goal. High uncertainty obtains in the case of post-Mao China. During this period, party authorities have debated how to cross the river of economic change. The party leadership has proceeded by “feeling for stones” each step of the way, and this oft-invoked metaphor captures the party’s heightened uncertainty over policy and governance matters in recent decades. Introducing competition to areas deemed critically important to party rule thus increases confidence in the ability of the system to weather through unpredictable environments.

The introduction of competition to a particular bureaucratic function does not imply privatization. Competition may take place solely between government and/or party bureaus, and this should still yield the outcome of greater system adaptiveness and innovation. Introducing private actors is one option among many for diversifying the range of players in a competition, which in turn should incentivize organizational creativity (Miranda and Lerner Reference Miranda and Lerner1995). Subjecting a bureaucratic agency to competition implies greater diversity in organizational activity, the search for an edge over rivals, and ultimately some innovation at the system level, but the participation of private market actors is not a necessary precondition for these processes to unfold.

Some additional design considerations accompany the decision to build a redundant bureaucratic system. Competition will lead to the highest levels of creativity when three conditions prevail.Footnote 41 Downs (Reference Downs1967) asserts that competing agencies must be close enough in purpose that their funding derives from the same sources. This transforms competition into a zero-sum scenario, which raises the stakes for success and agency survival. Second, these agencies must be distant enough in purpose that there is no significant exchange of personnel between them. Significant overlaps in human capital may decrease overall creativity. Third, rival agencies must possess discretion over which programs to pursue (Bendor Reference Bendor1985). Krause and Douglas (Reference Krause and Douglas2003) have also argued convincingly that competition is effective only when new entrants offer alternatives that are of similar or higher quality than the original monopoly agency. If competition presents an inferior standard, this has the perverse outcome of lowering standards throughout the system.

Several problems can attend the introduction of competition to a bureaucracy. There is the possibility of unpredicted interactions between agencies in a competitive system and the unknown outcomes these may produce. Ironically, while redundancy may be introduced to mitigate uncertainty, it can introduce uncertainties of its own. These uncertainties can include whether innovations preserve the existing system or plant the seeds of instability. In a hierarchical political system such as China’s, innovations often carry the risk of strengthening the hand of locales against that of the central state. Another concern is the opportunity cost of devoting resources to a redundant function when those resources might be committed elsewhere. The problem here is the difficulty in assigning costs to a given outcome as well as observing the counterfactual case. There are also deeper considerations such as coping with the possibility of market failure and the suitability of redundant systems for nonexclusionary goods.Footnote 42 There is no easy means to dismiss these issues. Safeguards against market failure will inevitably constrain the extent of competition that is possible or safe to introduce into a system. Nonexclusionary goods, on the other hand, may be amenable to competition. Classic examples, such as defense and security, do contain high degrees of overlap in agency jurisdiction (Bendor Reference Bendor1985: 3–22; Felsenthal Reference Felsenthal1980). Overall, these critiques present some limits on the universal application of redundancy to government functions.

Finally, bureaucratic competition cannot be imposed without expectation of resistance or complication. Introducing redundancy to a system entails a series of strategic decisions. Principals must first decide whether or not to create a redundant system at all and whether to assign agents to similar tasks or otherwise determine the range of choice, and then agents must choose how much effort to expend based on their particular policy preferences (Ting Reference Ting2003). This sets up the expectation that the “old guard” will resist the introduction of competition. Whether and how monopolistic agencies resist the introduction of competition is an additional focus of the empirical chapters of this book.

In sum, competition may appear to fly in the face of the bureaucratic tendency toward monopoly, particularly in a highly centralized authoritarian regime. Yet, as Bendor (Reference Bendor1985) points out, this preference is not based on empirical tests of the various advantages of monopoly over competition in matters of public administration: “the empirical warrant for monopoly in government … is virtually nonexistent” (p. 252). Crucially, Niskanen (Reference Niskanen1971) finds that a monopolistic public bureau is not more efficient than systems with overlapping or competitive bureaus.Footnote 43 Aversion to innovation by monopoly agencies within the CCP lies at the heart of the party’s concern with the old state of affairs in cadre training. As this study demonstrates, central party authorities deliberately turned to market-based competition to induce change in these party organizations.

Bringing in market processes

Interagency competition is one among several changes that have affected cadre training in China. Over the past three decades, reforms within party bureaus have taken a market turn. This marketization encompasses a bundle of processes that have resulted in the creation of a new organizational environment for cadre training. Ideally, markets comprise three interrelated processes: free exchange between buyers and sellers for a good or service, prices dictated by supply and demand, and free entry and exit of market actors. All of these characterize, to some degree, cadre training in China today. Marketization has remained incomplete due to significant interference by the party and continued dominance of party actors. The response of party schools to these changes is also shaped by additional market opportunities which have emerged in the reform period. The market in cadre training exists alongside more general markets for the goods and services that entrepreneurial school leaders may choose to offer: leases for plots of school land, facilities rentals, tourist services, and so forth.

Subsequent chapters will detail developments in both of these markets. There is now a broader range of sellers of cadre training services, including Chinese universities, training schools managed by various bureaus of the party, and schools located abroad. These sellers alternately compete for or are allocated training contracts. Buyers of cadre training content have diversified as well. These actors now include bureaus of the party-state, private-sector entrepreneurs, and everyday citizens. All have become consumers of the myriad services offered on party school campuses. Prices for training courses continue to be subject to negotiation between party actors, but party schools must also compete with bids from outside sellers. No longer are exchanges dictated by one- and five-year training plans. Still, party authorities retain the authority and ability to interfere with these exchanges, as training plans and ad hoc dictates from central authorities still determine, to a degree, the activity of party schools. Importantly, there exist distortions in the free entry and exit of training providers. While non-party providers may enter and exit at will, party schools may not shutter their doors. Party schools remain a privileged category of training providers. Many of these schools are still guaranteed some minimal floor of training revenue, though schools often supplement these with additional entrepreneurial activities.

Among market processes, subjecting party schools to competitive pressures has generated the strongest incentives for organizational change. This is because “markets promote high-powered incentives and restrain bureaucratic distortions more effectively than internal organization” (Williamson Reference Williamson, Schmalensee and Willig1989: 150). Since some degree of risk accompanies market-based competition, the stakes are higher than for a monopolistic bureaucracy. A market in which competitors enter and exit freely may mitigate the problem of determining when there are a sufficient number of actors in a system. One predicament facing planners is ascertaining how many agencies, or how many providers of a service, is optimal. To resolve this, it is possible to apply a satisficing principle, or ceasing expansion when some minimum threshold of competition is reached (Simon Reference Simon1979). A market configuration presents a more self-regulating solution. Where there is market-based competition, actors will continue to enter the market for a particular good or service until there is no longer a marginal gain for additional entrants.

A case study of cadre training in China contributes to understanding the processes of creating a competitive system where there was previously monopoly. Introducing competition, and not only uncompetitive redundancy, to party organizations in China has resulted in party entrepreneurialism. Party entrepreneurialism, as a response to heightened market-based competition for resources, encompasses several interrelated activities that include updated service provision, programmatic innovation, and the search for lucrative new ventures.Footnote 44 Some of these activities reflect significant changes in the substance of cadre training in China, and other activities are more limited (and local) in scope. All indicate the party’s capacity for significant organizational rethinking behind the veneer of a relatively unchanged political structure.

Précis of study

This study argues that the CCP has selectively enhanced the adaptability of subparty organizations by employing market mechanisms to incentivize organizational change. Party schools, as relatively understudied sites of political control and bureaucratic management, offer a window into the restructuring of incentives and how the CCP has exhibited surprising adaptability in the face of significant economic and social change. Competition between providers of cadre education has spilled beyond the boundaries of the party-state, but a key motivation has been to improve the adaptive capacity of party organizations. This argument raises several questions: What were the processes by which party authorities introduced competition to a bureaucratic realm previously dominated by one set of party organizations? Who was allowed to compete and why? What have been the organizational responses to this competition? What are some ways to measure organizational change? Have there been unintended consequences, either welcome or not? Are party schools still relevant? Findings at two levels of analysis offer answers to these questions. Individual-level career patterns and the “treatment” of party school training on career paths show that party schools remain an organized means for the party to manage critical processes of political elite selection. In carrying out this selection function, the party school system has been subject to competitive pressures. School-level analysis will map out organizational responses to centrally driven reforms and new policies.

Chapter 2 begins with an overview of the party school system, its history, and organizational context. Existing research on party schools is classified into roughly two groups: studies that focus on the functions of the Central Party School (CPS) and those that look at the school system beyond Beijing. Scholars have focused on party schools as indicators and drivers of ideological change within the party. This study, however, takes a different tack and emphasizes processes of organizational change as they unfolded throughout the system, in the CPS and beyond. This chapter also presents an intraparty comparison to demonstrate that not all party institutions have fared as well as party schools in the reform period; party schools have become more robust while other Mao-era institutions of political control, such as the campaign, have waned in importance.

In light of the reform-era investment in cadre training, Chapter 3 explores the theoretical and empirical relationship between cadre training and elite selection. In the principal–agent relationships which suffuse the Chinese political system, the party’s selection problem comes prior to other problems, more commonly studied, in a principal–agent relationship (i.e., moral hazard, which is solved by monitoring, rewards, and sanctions). This chapter tests whether selection for training at a party school constitutes a channel for promotion to higher cadre office. By employing a matching method on survey data, to control for selection bias, this chapter presents findings from analysis of a national sample of individuals on an administrative and/or political career track as well as results from an original dataset of the career histories of Central Party School trainees. It considers mechanisms for selection, including screening and signaling.

Chapter 4 shifts the level of analysis to discuss the marketization of cadre training, uncovering how market mechanisms were introduced to the party school system. Beginning in the mid-1980s, different sets of preexisting and new organizations were allowed to enter a cadre training market. At the same time, party schools were also allowed to engage in market activity that extended beyond their core training work. These two sets of market opportunities emerged via top-down, center-led processes, which local actors then seized for local gain and to effect system-wide change. Some intentionality can be deduced from central policy documents, while field interviews reveal that a combination of collaboration and rivalry characterizes the relationship between the organizations that now compete for cadre training contracts.Footnote 45 This chapter also discusses an important precondition to this marketization strategy, that is, limited fiscal and administrative decentralization.

Chapters 5 and 6 peer inside party schools to unpack the various school responses to competition and the development of an “entrepreneurial sensibility” within these organizations (Eisinger Reference Eisinger1988). Party school leaders have pursued a variety of income-raising schemes, some of which exist purely for pecuniary gain, while others attract income as well as improve the quality of schools’ training outputs. Changes observed in the party school system have parallels in the commercialization of China’s media, though differences exist due to variation in the core missions of these organizations. Chapter 6 presents indicators of adaptive change and applies them to content analysis of training syllabi from party schools at the central and local levels. Taken together, these varieties of party school activity demonstrate the range of organizational responses to competition. Site visits to training organizations at the central, provincial, city, and county levels form the basis for case studies of party school adaptation across regions with varying levels of economic development (Appendix B). In all locales, party school adaptation is a function of organizational responses to two markets: the market opportunities created by Deng’s liberalizing economic reforms and the pressures presented by a second market in which a variety of party-approved organizations compete for trainees. Schools have adapted to two imperatives: maximizing income streams in a new market economy and updating the content of cadre training.

The concluding chapter considers the implications of these changes. One result of party schools’ search for new income-generating projects has been greater embeddedness in local economies. This trend speaks to larger questions of the tension between party efforts to remain relevant and at the forefront of China’s economic development while avoiding the danger of granting too much autonomy to local actors. Looking beyond the China case, the theory and findings presented here offer an explanation for how a hierarchical ruling party may develop the capacity to adapt to systemic shocks and uncertainty. In China, change initiated in one realm has created pressures for adaptation in others: the decision to introduce market reforms to China’s state-managed economic sector has motivated shifts in the organizational geography and survival strategies of political institutions. This dynamism challenges accounts of the brittleness and inertia of communist-party-led systems.Footnote 46 The particular approach chosen by the CCP, that is, introducing market incentives to organizations of political control, suggests the diffusion of market principles beyond the economic realm to the political. In creating a training market to introduce competition to the party school system, the party leadership has sought to put in place incentives for continual adaptation by party institutions, at the same time retaining the party’s hold on the loyalties and careers of ambitious cadres.