Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Part 1 Works

- Part 2 Impact

- Part 3 Approaches

- 9 King's Contestatory Intertextualities: Sacred and Secular, Western and Indigenous

- 10 Thomas King's Humorous Traps

- 11 “Have I Got Stories—” and “Coyote Was There”: Thomas King's Use of Trickster Figures and the Transformation of Traditional Materials

- 12 “One Good Story”: Storytelling and Orality in Thomas King's Work

- 13 Maps, Borders, and Cultural Citizenship: Cartographic Negotiations in Thomas King's Work

- 14 One Good Protest: Thomas King, Indian Policy, and American Indian Activism

- 15 “Sometimes It Works and Sometimes It Doesn't”: Gender Blending and the Limits of Border Crossing in Green Grass, Running Water and Truth & Bright Water

- Part 4 Encounters

- Part 5 Thomas King—A Bibliography

- Notes on the Contributors

- Index

14 - One Good Protest: Thomas King, Indian Policy, and American Indian Activism

from Part 3 - Approaches

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 February 2013

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Part 1 Works

- Part 2 Impact

- Part 3 Approaches

- 9 King's Contestatory Intertextualities: Sacred and Secular, Western and Indigenous

- 10 Thomas King's Humorous Traps

- 11 “Have I Got Stories—” and “Coyote Was There”: Thomas King's Use of Trickster Figures and the Transformation of Traditional Materials

- 12 “One Good Story”: Storytelling and Orality in Thomas King's Work

- 13 Maps, Borders, and Cultural Citizenship: Cartographic Negotiations in Thomas King's Work

- 14 One Good Protest: Thomas King, Indian Policy, and American Indian Activism

- 15 “Sometimes It Works and Sometimes It Doesn't”: Gender Blending and the Limits of Border Crossing in Green Grass, Running Water and Truth & Bright Water

- Part 4 Encounters

- Part 5 Thomas King—A Bibliography

- Notes on the Contributors

- Index

Summary

Thomas King published major works prior to and simultaneously with a shift in the primary focus of American Indian literary critical inquiry from issues of culture and identity to questions of history and politics. Much of the early scholarship on King's fiction, therefore, approaches it with an interest in identities and storytelling strategies and assesses its cultural, multicultural, and crosscultural character. The attention to American Indian intellectual, activist, and tribal nation specific histories by Osage scholar Robert Warrior (1995), Cherokee scholar Jace Weaver (1997), and Muscogee Creek and Cherokee scholar Craig Womack (1999) shapes more recent critical work, for example, by Daniel Justice (Cherokee), who elucidates the Cherokee histories of removal that inform a novel such as Truth & Bright Water. My essay continues to account for King's work within the context of this new critical emphasis by assessing the role of US and Canadian Indian policies and American Indian and First Nations activism in his fiction. King's anticolonial exasperation at the former maintains an uneasy tension with his antifundamentalist skepticism of the latter. This antifundamentalism informs both the strategy of disguising his own anticolonial outrage in allegory or filtering it through often obscure historical references and his depiction of American Indian activists as one-dimensional dogmatists.

While US and Canadian Indian policies structure the fictional worlds of the novel Green Grass, Running Water and short stories such as “Joe the Painter and the Deer Island Massacre,” “A Short History of Indians in Canada,” and “Tidings of Comfort and Joy,” King does not make explicit the direct correlation between these policies and the contemporary lives of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

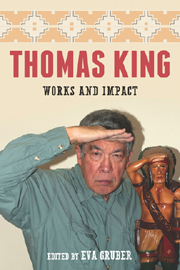

- Thomas KingWorks and Impact, pp. 224 - 237Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2012