Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue: Emazambaneni: The land of terror

- 1 The spectre of the human potato

- 2 Whose eyes are looking at history?

- 3 Bethal, the house of God

- 4 Violence: The white farmers’ fears erupt

- 5 These eyes are looking for a home

- 6 Bethal today

- 7 Our eschatological future

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

2 - Whose eyes are looking at history?

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 March 2024

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue: Emazambaneni: The land of terror

- 1 The spectre of the human potato

- 2 Whose eyes are looking at history?

- 3 Bethal, the house of God

- 4 Violence: The white farmers’ fears erupt

- 5 These eyes are looking for a home

- 6 Bethal today

- 7 Our eschatological future

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

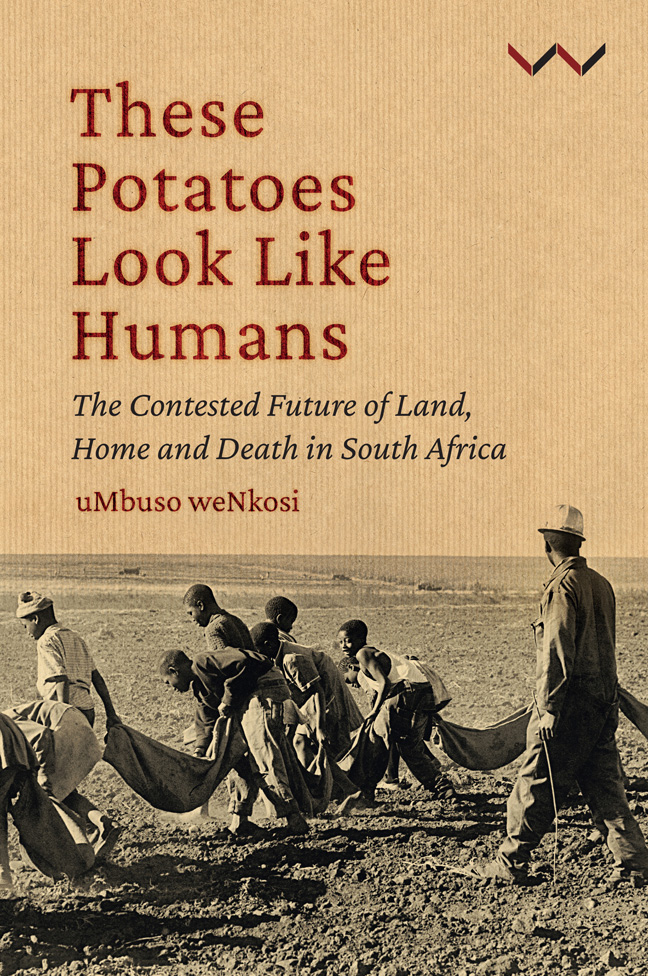

Mrs Kgobadi carried a sick baby when the eviction took place … Two days out the little one began to sink as the result of privation and exposure on the road … its little soul was released from its earthly bonds … They [Kgobadi family] had no right or title to the farm lands through which they trekked: they must keep to the public roads – the only places in the country open to the outcasts if they are possessed of a travelling permit. The deceased child had to be buried, but where, when, and how? This young wandering family decided to dig a grave under cover of the darkness of that night, when no one was looking, and in that crude manner the dead child was interred – and interred amid fear and trembling, as well as the throbs of a torturing anguish, in a stolen grave, lest the proprietor of the spot, or any of his servants, should surprise them in the act.

— Solomon PlaatjeThe anguish of dispossession in South Africa is neither the untold truths nor the many spoken truths of how a family, in the place of their birth, ended up stealing a grave. The anguish comes from the eyes of the ones who had to steal the grave and bury their own in a hurry. As if that is not enough, the moment of dispossession is thought of today as part of a vile past that is no longer relevant to us.

The history of dispossession in South Africa should instead be seen as part of our historical present. Our history is forever present in our social order. To locate it, we need to look deeply into South Africa's vast hectares of land. What we might excavate will be ugly, but it will also reveal the deeper meaning of dispossession – that once people are removed from the land, not only do they become slaves, they also become ‘criminals’ whose entire existence is a journey to nowhere.

This is a condition of ontological nowhereness as exemplified in Solomon Plaatje's Native Life in South Africa, where he documents how the 1913 Land Act made criminals of all those Black people (labour tenants) who refused to abide by the law which stipulated that they would become servants of the farmer and work the land along with their cattle.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- These Potatoes Look Like HumansThe Contested Future of Land, Home and Death in South Africa, pp. 31 - 50Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2023