Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue: Emazambaneni: The land of terror

- 1 The spectre of the human potato

- 2 Whose eyes are looking at history?

- 3 Bethal, the house of God

- 4 Violence: The white farmers’ fears erupt

- 5 These eyes are looking for a home

- 6 Bethal today

- 7 Our eschatological future

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Prologue: Emazambaneni: The land of terror

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 March 2024

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue: Emazambaneni: The land of terror

- 1 The spectre of the human potato

- 2 Whose eyes are looking at history?

- 3 Bethal, the house of God

- 4 Violence: The white farmers’ fears erupt

- 5 These eyes are looking for a home

- 6 Bethal today

- 7 Our eschatological future

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

Imagine that you are lost in a twisted world with no one to depend on. When you bleed, no matter how much you shout and scream, no one comes. All you have is hope – hope that someone will hear your cry and that salvation will come. Hope that someone will at least recognise you as a human being, with blood and life in your veins.

Then imagine that this is not some imaginary world you’ve been thrown into. It is your world. It is your home. Not only this, but history reminds you that you are linked to great ancestors who once lived in it.

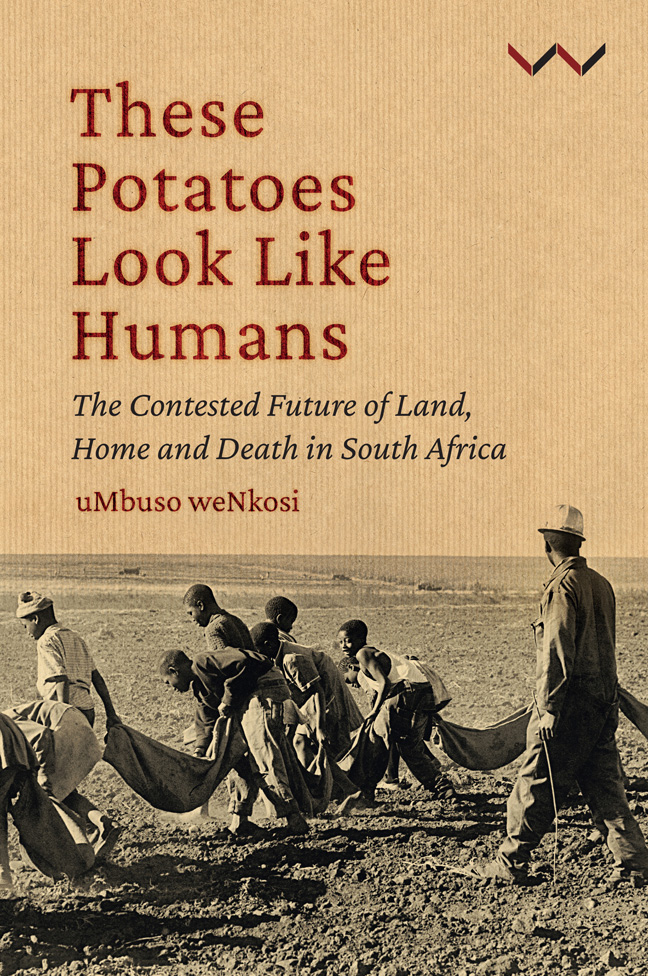

Now bring the land into closer focus – farmland in the region of the Eastern Transvaal (now Mpumalanga), South Africa, and a small rural town named Bethal.

It is here where, in 1954, an unidentified man takes ‘a great opportunity to write … these few lines …’ His letter is intended for the head of the Department of Prisons in Pretoria and he is writing from Leslie jail, on behalf of himself and his fellow inmates. By doing so he is risking his life.

In fact, it is not a letter: it is a desperate plea. The terror is palpable. The struggle to hold on to the little breath of life that might get snatched away is evident in every line (see figure 0.1).

This letter was one of the first things I read about Bethal when I was working on my PhD research project. It lies in the Historical Papers Research Archive at Wits University, the accompanying information being that it was smuggled out of the jail and into the hands of William Barney Ngakane, who shared it with Henri-Philippe Junod on 15 March 1954.

In the 1950s, the spotlight in South African history shifted from resistance politics in the urban areas to a scandal in this small rural town. The area, which was known for potato farming, was called ‘emazambaneni’ (the land of potatoes) by the workers and the community members, and there was a song they sang: ‘khona le eBethal siyoghuba amazambane’ (there in Bethal where we will be digging potatoes). The song aimed to capture the brutality and violence that was happening on the Bethal potato farms. This violence was not new, however.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- These Potatoes Look Like HumansThe Contested Future of Land, Home and Death in South Africa, pp. 1 - 10Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2023