Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue: Emazambaneni: The land of terror

- 1 The spectre of the human potato

- 2 Whose eyes are looking at history?

- 3 Bethal, the house of God

- 4 Violence: The white farmers’ fears erupt

- 5 These eyes are looking for a home

- 6 Bethal today

- 7 Our eschatological future

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

6 - Bethal today

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 March 2024

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue: Emazambaneni: The land of terror

- 1 The spectre of the human potato

- 2 Whose eyes are looking at history?

- 3 Bethal, the house of God

- 4 Violence: The white farmers’ fears erupt

- 5 These eyes are looking for a home

- 6 Bethal today

- 7 Our eschatological future

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

In moving to the present, it becomes clear that the ontological nowhereness characterised as the search for somewhere to live and die represents the ongoing resistance against being landless. As we move to the present, we arrive at the condition of a place that exists somewhere, a place called home, a place where the dead rest and a place where the living will also rest when they are dead. This is the Bethal of today, a Bethal of the present, where contestation reflects an ongoing historical cycle, where the present always reflects our past. Our present is a historical present – a past present with us, whose presence represents the unresolved history of our present spiritual moment. To visit Bethal today, in the present, is to revisit the past. The violence of dispossession entails an eschatological gaze, which means that the spirit of the past remains in this land.

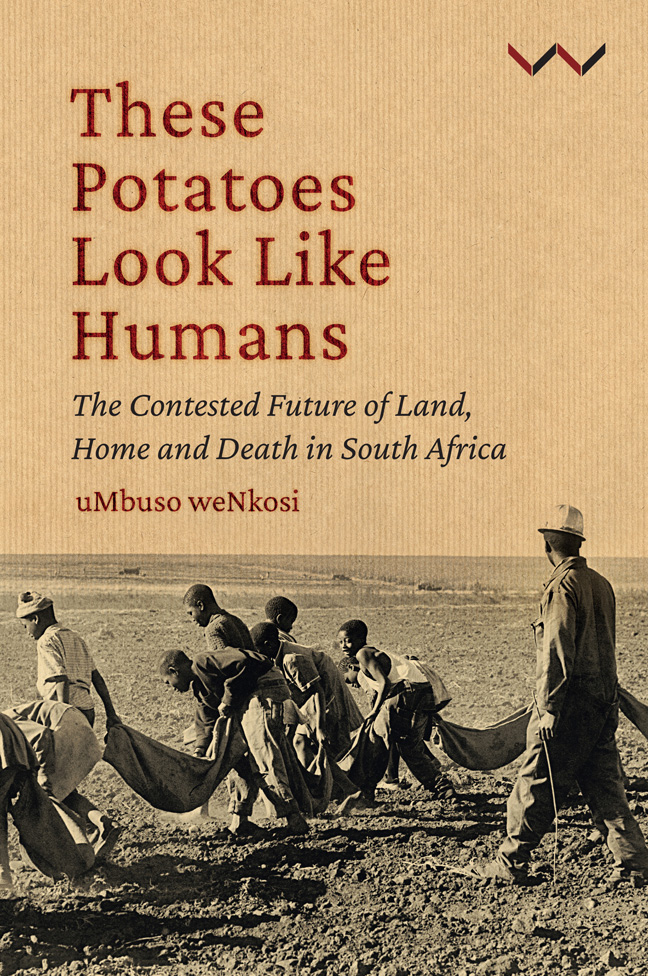

I have been arguing that we do not need to see the land only through an economic lens. To see it as such is a form of debasement that renders us part of the ontology of violence of ownership which conceals anxiety about the future. To visit Bethal today is to arrive at the future. That is why when Jürgen Schadeberg (the renowned photographer who was a friend and colleague of Henry Nxumalo at the time of the Drum exposé) visited Bethal in April 2005 with Styles Ledwaba, they were to write that ‘53 years after Nxumalo's exposé … although the whips and the forced labour are gone, farmworkers in the area face a struggle of a different kind’. Schadeberg had been familiar with Bethal since 1952, when, with Nxumalo, he had posed as a German tourist and had managed to take some pictures of the compounds. Schadeberg also helped Nxumalo escape from the farm that was part of the subsequent Drum story, where he had taken pictures of farmworkers carrying sacks of potatoes in the field. Another picture was of a ‘boss-boy’ with a whip riding a horse in a maize field (see figure 3.2).

In going to Bethal today, I am going to the places where the violence took place, to understand the spiritual meaning of this past in the present and the future (see figure 6.1 showing the farms visited). I am not alone. Xender Ehlers is my interlocutor, taking me to the farms.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- These Potatoes Look Like HumansThe Contested Future of Land, Home and Death in South Africa, pp. 115 - 130Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2023