In recent years, numerous books and articles have been written about Bronze Age textiles, woollen textile production in particular, from the Mediterranean and the Near East. This volume encompasses a wide range of studies aiming to broaden the horizon, and, in the light of recent scientific advances, to shift the focus to continental and northern Europe. Iconographical and archaeological evidence shows that Bronze Age Europe was not only a dressed world, but also one that was open to innovation as far as fibres and textile technology are concerned. Since technological innovations necessarily affected economic and social frameworks, this whole work maintains that the study of textile production holds great potential for enhancing our understanding of the Bronze Age world.

Introduction

In Bronze Age studies, research about textiles and textile production has gained increasing attention in recent years (e.g. Andersson Strand and Nosch Reference Nosch, Weilhartner and Ruppenstein2015; Barber Reference Barber1991; Bazzanella et al. Reference Bazzanella, Mayr, Moser and Rast-Eicher2003; Bender Jørgensen Reference Bender Jørgensen1992; Bender Jørgensen et al. Reference Bender Jørgensen, Rast-Eicher, Ehlers and Fossøy2016, Reference Bender Jørgensen, Sofaer and Sørensen2018; Bergerbrant Reference Bergerbrant, Andersson Strand, Gleba, Mannering, Munkholt and Ringgaard2010; Breniquet and Michel Reference Breniquet and Michel2014; Gillis and Nosch Reference Gillis and Nosch2007; Gleba and Mannering Reference Gleba and Mannering2012; Grömer et al. Reference Grömer, Kern, Reschreiter and Rösel-Mautendorfer2013; Harlow et al. Reference Harlow, Michel and Nosch2014; Nosch Reference Nosch2011; Sofaer et al. Reference Sofaer, Bender Jørgensen, Choyke, Harding and Fokkens2014). Owing to the quality and characteristics of the available textual and archaeological sources, a significant part of the achieved results relates to three specific regions: the Aegean and the eastern Mediterranean area, northern Europe, and the Hallstatt salt mines in central Europe. However, the characteristics of the available records vary greatly across those areas (see below). In other words, rather than a comprehensive picture in any area, we have an exciting – but incomplete – puzzle, comprising many kinds of information, and numerous issues remain to be investigated.

With an eye that is attentive to the rich comparative evidence from the Mediterranean and to a solid tradition of fibre analyses and technological issues, the main focus of this volume is upon the Bronze Age in continental Europe. A diverse range of ideas, reflections and approaches covering more than a millennium of ‘fashion’, textile and textile production are offered through the coming pages. Yet, the primary aim of this collection of chapters is not to be exhaustive in terms of chronology or geography. Instead, it seeks to offer a broad range of what appears at the time of writing to be the most up-to-date ways to approach Bronze Age textiles and textile production, fruitfully uniting the natural sciences and more traditional archaeological approaches. Our main goal is twofold: on the one hand, we wish to provide significant samples of assorted archaeological approaches to the study of both textile tools and textile fragments (see the chapters by Andersson Strand and Nosch, Bergerbrant, Harris, Kneisel and Schaefer-Di Maida, Sabatini, Schaefer-Di Maida and Kneisel, and Słomska and Antosik), showing at the same time both regional variability and supra-regional similarities throughout the continent; on the other hand, we also present a series of chapters discussing relevant natural scientific and methodological approaches (see the chapters by Brandt and Allentoft, Carrer and Migliavacca, Di Gianvincenzo et al., Frei, and Skals), which significantly augment our understanding of specific aspects of textile production as well as reinforcing the overarching picture.

All in all, the blend of contributions presented in this volume shows the potential that new interdisciplinary collaborations have for achieving a deeper understanding of ancient textile economies (see also Chapter 14 by Kristiansen and Sørensen).

Bronze Age Textile Production

The earliest known Eurasian textile fragments date back to the seventh/sixth millennium bc and are made from vegetable fibres (Barber Reference Barber1991, 10–12; Bender Jørgensen Reference Bender Jørgensen1992, 116; Breniquet and Michel Reference Breniquet and Michel2014, 2; Rottoli Reference Rottoli, Bazzanella, Mayr, Moser and Rast-Eicher2003). Woollen textiles seem to be a later invention; the first likely evidence for wool production dates to the fourth millennium bc and is found in ancient written texts from Mesopotamia (Barber Reference Barber1991, 24; see also Chapter 2 by Andersson Strand and Nosch). More abundant texts show that intense production and trade of woollen textiles were taking place in the Near East from the third millennium bc and in the Aegean from the second millennium bc (Breniquet and Michel Reference Breniquet and Michel2014; Burke Reference Burke and Cline2010; Del Freo et al. Reference Del Freo, Nosch, Rougemont, Michel and Nosch2010; Killen Reference Killen, Gillis and Nosch2007; Michel and Nosch Reference Michel and Nosch2010; Nosch Reference Nosch2011, Reference Nosch, Weilhartner and Ruppenstein2015; Waetzoldt Reference Waetzoldt1972; Wisti Lassen Reference Wisti Lassen2010; Wright Reference Wright and Crawford2013; see also Chapter 2 by Andersson Strand and Nosch). Considering that there are hardly any preserved textiles from these areas, and that almost all of the known fragments are made of vegetable fibres (Skals et al. Reference Skals, Möller-Wiering, Nosch, Andersson Strand and Nosch2015), without the texts we would have very few or virtually no archaeological indications of wool production and its economic importance. This is a lesson worth remembering when studying other regions.

The production of fibres has a considerable cost, in terms of both dedicated workforce and landscape management (e.g. Andersson Strand and Cybulska Reference Andersson Strand, Cybulska, Nosch, Koefoed and Andersson Strand2012; Biga Reference Biga, Breniquet and Michel2014; McCorriston Reference McCorriston1997; Nosch Reference Nosch, Breniquet and Michel2014). Both animals and plants need a vast portion of the landscape to grow and develop, territories that have to be managed to leave space for agriculture for food production. Calculations based on medieval documentation from Scandinavia (Bender Jørgensen Reference Bender Jørgensen, Berge, Jasinski and Sognnes2012) suggest that the equation requires complex and locally specific strategies. As far as wool production is concerned, it is clear from the ancient sources that primitive sheep did not produce a large amount of wool per year (Barber Reference Barber1991, 24–30; Del Freo et al. Reference Del Freo, Nosch, Rougemont, Michel and Nosch2010; Firth Reference Firth, Nakassis, Gulizio and James2014; Killen Reference Killen, Gillis and Nosch2007), thus large flocks were necessary in order to manage a consistent wool production. The study of any ancient wool economy therefore requires, among other things (see also Sabatini Reference Sabatini2018), a thorough discussion of issues relating to sheep husbandry and of the environmental sustainability of large herds. In contrast to plants, animals can move, allowing a more integrated use of the surrounding landscapes; however, movement requires planning as well as social, cultural and economic infrastructures, not least the management of mobile human resources to follow and care for the herds (Becker et al Reference Becker, Benecke, Grabundžija, Küchelmann, Pollock, Schier, Schoch, Schrakamp, Schütt, Schumacher, Graßhoff and Meyer2016; McCorriston Reference McCorriston1997; Ryder Reference Ryder1983; see also Chapter 9 by Carrer and Migliavacca).

The chapters in this book not only highlight the sparse, but significant, evidence for the production and use of various textiles and fibres, but also clearly suggest that, in addition to some general trends, textile economies are contingent upon a wealth of regionally specific processes and constraints. This means that the study of Bronze Age textile production and specialisation necessarily requires close attention to be paid to the interplay between the local and the continental.

Textile Tools

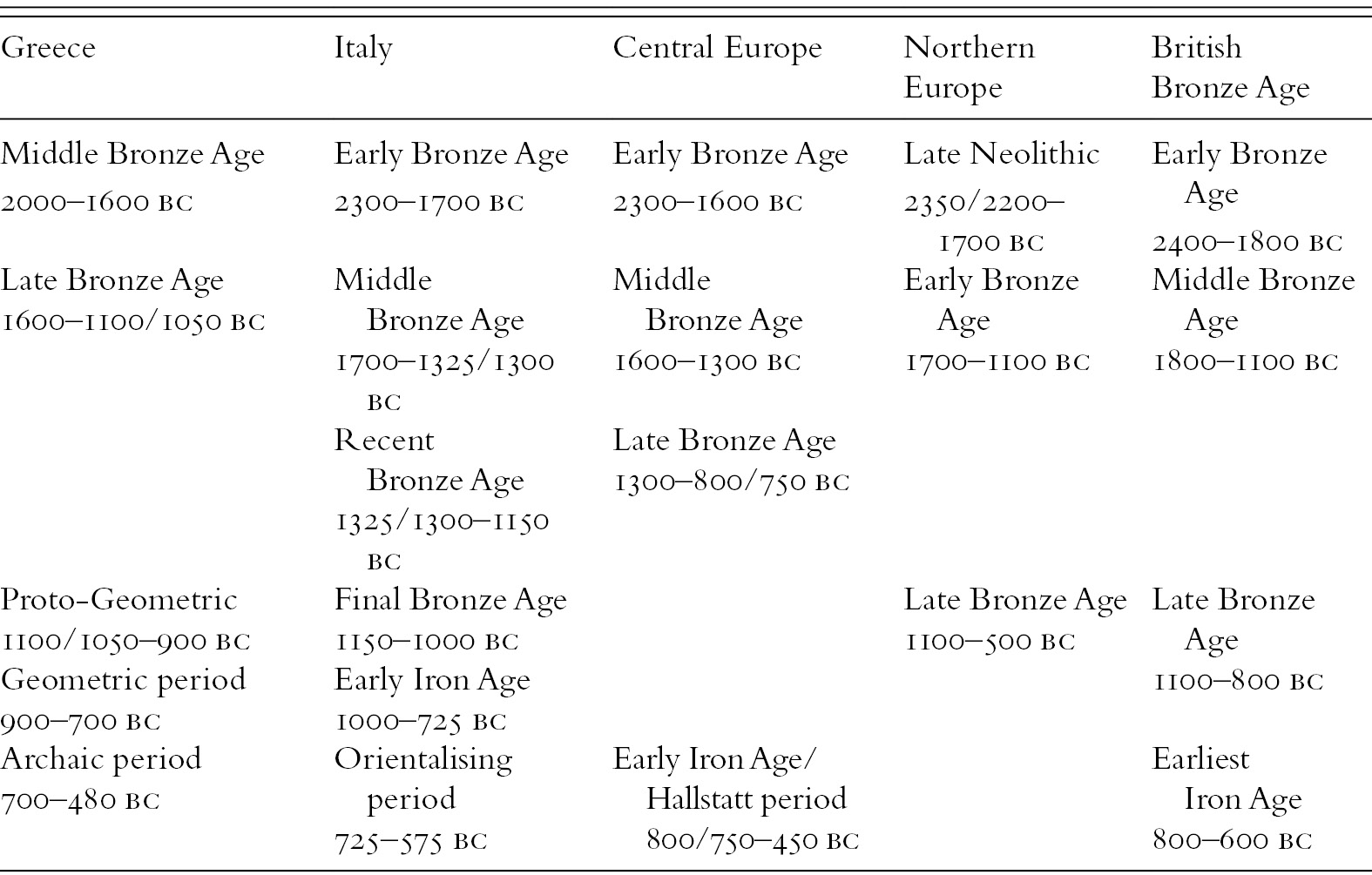

Textile tools such as spindle whorls and loom weights, which are generally produced in non-perishable material such as clay and stone (see Chapter 2 by Andersson Strand and Nosch, Chapter 3 by Sabatini and Chapter 4 by Kneisel and Schaefer-Di Maida), represent very good evidence for textile production (see e.g. Barber Reference Barber1991, 39–125; Bender Jørgensen Reference Bender Jørgensen, Bender Jørgensen, Sofaer and Sørensen2018; Burke Reference Burke and Cline2010; Gleba Reference Gleba2008, 100–153), although they do not inform about the type of fibres used, nor does their presence/absence always match the information from the written sources, when those exist. In this respect, textile production in the Late Bronze Age Aegean (approximately 1600–1200 bc; see Table 1.1) is an interesting case in point. According to the numerous archive documents from Mycenaean palaces, textile production is a fundamental component of the local economy, requiring a conspicuous and specialised workforce and the management of animal and landscape resources (Del Freo et al. Reference Del Freo, Nosch, Rougemont, Michel and Nosch2010; Firth Reference Firth, Nakassis, Gulizio and James2014; Killen Reference Killen, Gillis and Nosch2007; Nosch Reference Nosch2011, Reference Nosch, Weilhartner and Ruppenstein2015). However, the archaeological evidence for textile tools is scarce and does not reflect the prominent place occupied by this economic activity (e.g. Burke Reference Burke and Cline2010, 437; Sabatini Reference Sabatini2016, 230–232; Siennicka Reference Siennicka and Droβ-Krüpe2014; Tournavitou et al. Reference Tournavitou, Andersson Strand, Nosch, Cutler, Andersson Strand and Nosch2015, 262). Textile tools can also be used to discuss various aspects of quality and characteristics of production. Chapter 2 by Andersson Strand and Nosch summarises the ten years of intense work on the Mediterranean at the Danish Centre for Textile Research (CTR). They show how fruitful interdisciplinary work invariably proves to be. The work at CTR showed that significant achievements can be made when the study of archaeological artefacts and textual sources is combined with the evidence from experimental archaeology. Indeed, they argue that a multidisciplinary approach seems to provide enlightening insights into the many unsolved questions concerning archaeological textiles.

Table 1.1 European Bronze Age chronology

| Greece | Italy | Central Europe | Northern Europe | British Bronze Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Middle Bronze Age | Early Bronze Age | Early Bronze Age | Late Neolithic | Early Bronze Age |

| 2000–1600 bc | 2300–1700 bc | 2300–1600 bc | 2350/2200–1700 bc | 2400–1800 bc |

| Late Bronze Age | Middle Bronze Age | Middle Bronze Age | Early Bronze Age | Middle Bronze Age |

| 1600–1100/1050 bc | 1700–1325/1300 bc | 1600–1300 bc | 1700–1100 bc | 1800–1100 bc |

| Recent Bronze Age | Late Bronze Age | |||

| 1325/1300–1150 bc | 1300–800/750 bc | |||

| Proto-Geometric | Final Bronze Age | Late Bronze Age | Late Bronze Age | |

| 1100/1050–900 bc | 1150–1000 bc | 1100–500 bc | 1100–800 bc | |

| Geometric period | Early Iron Age | |||

| 900–700 bc | 1000–725 bc | |||

| Archaic period | Orientalising period | Early Iron Age/ Hallstatt period | Earliest Iron Age | |

| 700–480 bc | 725–575 bc | 800/750–450 bc | 800–600 bc |

Working on the sole archaeological evidence for textile tools, Sabatini’s contribution (Chapter 3) shows that the taxonomic and functional analyses of the archaeological material provide useful contributions for the understanding of the social and cultural organisation of production modes when interpreted using new theoretical models. Taking a community of practice model as a frame of reference, the careful analysis of differences and similarities between loom weights from Bronze Age sites of the Po plain in northern Italy has shown that local weaving was both site-specific and responsive to wider regional developments. The work also suggests the validity of such a model for explaining variation and development through time and space of crafts and technologies. The systematic overview in Chapter 4 by Kneisel and Schaefer-Di Maida of the published loom weights from central European sites dated to the Bronze and Iron Age (c. 2200–500 bc, Table 1.1) demonstrates the potential that accurate large-scale investigations may have for a deeper understanding of the spread and development of specific crafts. On the basis of their investigation, the authors argue that loom weights in central Europe appear to increase at the dawn of the Late Bronze Age and after, suggesting that textile production in certain areas became more profitable with time.

Textile Fragments

In continental Europe, where ancient textual sources are completely absent, specific environmental and climatic conditions have made possible the survival and preservation of a conspicuous number of Bronze Age textiles and clothing made of various fibres including wool (Bender Jørgensen and Rast-Eicher Reference Bender Jørgensen, Rast-Eicher, Bender Jørgensen, Sofaer and Sørensen2018; Gleba and Mannering Reference Gleba and Mannering2012). Some of the most famous textiles come from the so-called oak-log coffins found in present-day Denmark (Bergerbrant Reference Bergerbrant2007; Broholm and Hald Reference Broholm and Hald1940; Frei et al. Reference Frei, Mannering, Vanden Berghe and Kristiansen2017) and are generally dated between the end of the fifteenth and the thirteenth century bc (Holst et al. Reference Holst, Breunning-Madsen and Rasmussen2001). Another important collection of woollen textile has been retrieved from the Hallstatt salt mines in present-day Austria (Grömer Reference Grömer, Gleba and Mannering2012, Reference Grömer2016; Grömer et al. Reference Grömer, Kern, Reschreiter and Rösel-Mautendorfer2013) covering a long period of time from the Bronze to the Iron Age, though with gaps. A number of textile fragments generally made of flax fibres come from Alpine lake dwellings dating from the Neolithic to the Bronze Age (Bazzanella et al. Reference Bazzanella, Mayr, Moser and Rast-Eicher2003; Bazzanella and Mayr Reference Bazzanella and Mayr2009) and a limited number of other European areas (CinBA Database; Bender Jørgensen and Rast-Eicher Reference Bender Jørgensen, Rast-Eicher, Bender Jørgensen, Sofaer and Sørensen2018; Gleba and Mannering Reference Gleba and Mannering2012; Grömer et al. Reference Grömer, Bender Jørgensen and Marić Baković2018; Harding Reference Harding1995; Marić Baković and Car Reference Marić Baković and Car2014). Słomska and Antosik’s chapter (Chapter 5) adds a new and important piece of information to this corpus of continental textiles. Their contribution presents an overview of textile fragments found in the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age (c. 900–450 bc, Table 1.1) burials from Upper Silesia–Lesser Poland, in present-day Poland. Thanks to a detailed analysis of the preserved fragments, the authors are able to show that the Early Iron Age textiles included in their study were not only most likely produced locally, but also generally manufactured according to a fashion similar to the one that is known from the earlier Bronze Age textiles in the neighbouring Hallstatt cultures.

Even when they are preserved, the actual state of conservation of most textile fragments might not always allow imagining their original appearance,1 or even magnificence. Chapter 6 by Skals shows in detail the painstaking work of fibre analysis. Standard terminology for analysing textiles was developed between the 1960s and 1980s by experts such as Irene Emery, Penelope Walton and Gillian Eastwood. However, contemporary work with the development of fibre analysis methods has lately expanded the heuristic possibilities of the methods and provided the opportunity to gain information not only regarding fibre identification, but also with respect to the technology of the textile craft applied in the manufacture of each piece. Fibre analyses may therefore provide information as to spinning and weaving techniques as much as to the colours, fibre patterns and possible dyeing. The recently conducted analyses of the famous Danish Bronze and Iron Age clothing are used to illustrate the points made in the chapter.

Questions such as appearance and identity relating to clothing and textiles are approached by Harris (Chapter 7) in a unique and intriguing way. She discusses how archaeologists seem to feel almost uneasy when too many textile fragments are preserved. Given the lack of large comparative material, burial contexts with preserved textile remains are often isolated in the scientific literature. The chapter powerfully discusses issues of taphonomy, comparing contexts where organic material is preserved and those where only inorganic material has survived through time; it is argued that by focusing on organic materials, unexplored dynamics emerge, because through clothes and coverings the normally separated ‘usual’/inorganic burial assemblages (e.g. axes, beads) were actually joined together as a whole. Indeed, despite costs and difficulties connected to textile production chaînes opératoires, textiles must have been all over the place! Clothing and coverings must have populated the materiality of the European Bronze Age and likely played a very consistent role in discourses of social and cultural identity.

When textiles do not survive, other evidence can account for their existence, as demonstrated by the evidence for textile imprints on ceramics known from central and northern Europe. Chapter 8 by Schaefer-Di Maida and Kneisel uses the material from Bruszczewo, in present-day Poland, to demonstrate that it is possible to gain insights into local textile production even at sites where very few textile tools and no textile fragments have been preserved. Textile imprints appear to be a relatively underestimated source of information as to the quality and characteristics of the fabrics that were normally handled in the settlements. It is demonstrated that the information about textiles that can be gathered from the imprints is similar to that from textiles themselves, concerning, for example, spin direction, weave type, etc. Imprints therefore provide useful material for comparative studies with other areas where textiles may not have survived.

Mobility, Sheep, Wool and Textiles

It is widely accepted that during the second millennium bc the Euro-Mediterranean region was an arena for large exchange networks meeting a high demand for metal – particularly copper and tin (e.g. Earle et al. Reference Earle, Ling, Uhnér, Stos-Gale and Melheim2015; Kristiansen Reference Kristiansen, Kiriatzi and Knappet2016; Rowlands and Ling Reference Rowlands, Ling, Bergerbrant and Sabatini2013; Sabatini and Melheim Reference Sabatini, Melheim, Bergerbrant and Wessman2017; Sherratt and Sherratt Reference Sherratt, Sherratt and Gale1991; Vandkilde Reference Vandkilde2014). Recent research from Scandinavia (Ling et al. Reference Ling, Stos-Gale, Grandin, Billström, Hjärthner-Holdar and Persson2014; Melheim et al. Reference Melheim, Grandin, Persson, Billström, Stos-Gale, Ling, Williams, Angelini, Canovaro, Hjärthner-Holdar and Kristiansen2018) has been at the forefront in showing that a significant percentage of the copper used to produce the Nordic types of bronze artefacts during the Bronze Age was brought to the north from unexpectedly faraway sources (including the Mediterranean basin). Therefore, several networks must have been at work at the same time over the whole continent. The picture is complex and challenges the idea that raw materials, technologies and popular ‘styles’ (e.g. specific forms and decorations) may have come along the same exchange routes as has been generally postulated, for example for the Early Bronze Age Scandinavian bronze artefacts showing strong stylistic links to the copper-producing area of the Carpathian basin (e.g. Liversage Reference Liversage2000; Thrane Reference Thrane1975; Vandkilde Reference Vandkilde2014). Interdisciplinary investigations concerning the existence of a wide, although archaeologically barely visible, pastoral mobility and textile trade might provide invaluable support in explaining, among other things, stylistic similarities between regions that were likely not linked by other archaeologically recognisable forms of trade or networks. Chapter 9 by Carrer and Migliavacca provides an overview of prehistoric pastoral mobility in the northern Mediterranean area. It highlights the wider Bronze Age scholarship of the socio-economic and cultural impact of distinct husbandry strategies. It is shown that the phenomenon of transhumance had taken root in parts of Europe already during the Neolithic and appears to have experienced a slow transition, from unspecialised short-distance activity to a specialised long-distance strategy, during the Bronze Age. The attentive examination of the available archaeological evidence suggests that the evolution of pastoral mobility is deeply related to the emergence of social and economic complexity, the development of political control of the territory and the expansion of trading networks.

A considerable innovation in textile studies in general, and for the investigation of the early continental wool trading networks, has been introduced and developed in recent years with the application of strontium isotope tracing analyses on woollen thread samples (Frei et al. Reference Frei, Mannering, Kristiansen, Allentoft, Wilson, Skals, Tridico, Nosch, Willerslev, Clarke and Frei2015, Reference Frei, Mannering, Vanden Berghe and Kristiansen2017). The experiments carried out so far have shown that it is possible to measure the strontium signature of the wool that was used to make textiles and thus to provide information on whether the wool is local or non-local (Frei et al. Reference Frei, Frei, Mannering, Gleba, Nosch and Lyngstrøm2009). After introducing the reader to the strontium isotope tracing method, in Chapter 10 Frei presents a series of recent results from Danish Bronze Age textiles, showing that the majority of the samples were manufactured with fibres from a variety of geological environments. Frei’s work represents a great advance for the study of ancient textiles. It provides the scientific proof that Bronze Age textile production in general, and wool textile production in particular, rested (at least during the mid-second millennium bc) on a wide-ranging and complex system of production and exchange that probably linked various parts of the continent. Combining the results of strontium isotope analyses with a careful examination of the available archaeological records from northern Europe, the contribution by Bergerbrant (Chapter 11) takes a step forward and seeks to demonstrate that not only was a large proportion of the wool used to produce Scandinavian woollen textiles (or at least those preserved in the Danish oak-log coffins) not produced locally, but that most likely also the large pieces of textiles and clothing found in Nordic Bronze Age graves were traded from somewhere in Europe and not manufactured in Scandinavia. On the other hand, several technical details of the preserved fragments suggest that a local textile production was not totally lacking, and that items like the corded skirts and other smaller garments were probably made locally in northern Europe.

Textiles, Ancient DNA and Protein Residues

In recent years, the idea that archaeological studies are undergoing a scientific paradigm shift implying necessary collaboration with a variety of natural sciences to produce new knowledge about the past has entered the general scientific debate (e.g. Kristiansen Reference Kristiansen2014, Reference Frei, Mannering, Vanden Berghe and Kristiansen2017; Sabatini and Melheim Reference Sabatini, Melheim, Bergerbrant and Wessman2017; Vandkilde et al. Reference Vandkilde, Hansen, Kotsakis, Kristiansen, Müller, Sofaer, Sørensen, Suchowska-Ducke, Scott Reiter and Vandkilde2015). As widely acknowledged throughout this volume, interdisciplinary approaches to the study of textiles are the key issue in modern textile research. However, we wish to suggest that we may be far from having explored all the possible angles from which textiles could be studied. Two methods, yet to be fully explored and exploited, have been chosen for this volume: the study of ancient DNA and that of ancient protein residues. Both appear at the moment to hold great potential for future investigations.

Chapter 12 by Brandt and Allentoft provides an overview of recent research history and the current methodologies available for analysing ancient DNA, including possible limitations. The authors show in the first place that it is fully possible today to recover genetic data (in particular from mitochondrial DNA) from historical and archaeological woollen textiles. Nonetheless, they also discuss how preservation conditions of ancient DNA depend on a variety of factors, including ancient wool treatment processes and the characteristics of the environment in which textiles were buried. When available, ancient DNA represents an invaluable source of information as to the species that have been used to produce the samples and regarding their selection and domestication processes.

Chapter 13 by Di Gianvincenzo, Granzotto and Cappellini discusses the possibility offered by mass spectrometry-based ancient protein analysis. The method has been successfully used to investigate garments produced from proteinaceous sources, obtaining results as to the used species and some of their characteristics, as, for example, the slaughtering age. The use of ancient protein residues for the investigation of animal fibres and skins has so far been limited by the availability of public reference proteome databases. However, proteins have a very resistent molecular structure and appear to be preserved even when other conditions have eliminated any possibility of carrying out genetic studies. Thus, they represent a powerful tool for possibly providing new information about archaeological textiles and garments.

Both these contributions show that there are still many aspects of textiles to investigate and that there is great potential for enhancing the knowledge provided by the archaeological and textual evidence.

Wrapping Up

The concluding reflections by Kristiansen and Sørensen in Chapter 14 underscore the importance of wool not only as a new material, but as a new technology that substantially affected societies from, e.g., a social, economic and political point of view. They stress that this book brings the study of wool and textile production to the forefront of current Bronze Age research, intersecting with the major themes of the discipline. Prior to this, the possibility that wool production may have been as important as metallurgy had never been seriously entertained, but there is a new appreciation for its significance now. Kristiansen and Sørensen describe how our knowledge has changed in recent decades and provide useful suggestions for further research. We are just starting to understand the importance of wool and textile production, and how it must relate, for example, to the development of new subsistence strategies or to new trade ventures throughout the continent. They go a step further and attempt to contextualise the new understanding of wool and textile production within continental and demographic trends, and above all they attempt for the first time to quantify trade, providing an idea of the number of pieces of cloth that may have been needed in the specific case of Denmark during the Early Bronze Age. Their approach is challenging and wide-ranging, providing a demonstration of how one should look at the whole picture and not forget that different large-scale trade networks, such as those for copper, tin, salt and textiles, must have been active at the same time, affecting and shaping Bronze Age societies.

Concluding Remarks

We are confident that every contribution to this volume brings new material and/or theoretical and methodological approaches to the study of Bronze Age wool and textiles. In light of the growing amount of data and of the opportunities for combining results from geo-chemical and bio-genetic analyses with those from the study of the archaeological evidence from the small-scale studies to the broad overarching perspective, we share optimism about the future of textile research and the exciting new results waiting to be obtained.

In conclusion, we hope the volume will engage readers in the study of the prehistoric textile economy and inspire future interdisciplinary collaborations to deepen and extend our understanding of this tremendous human endeavour.