I Code of Obligations as the Main Source of Law

42 The most important source of Swiss contract law is the Code of Obligations of 30 March 1911. The Code of Obligations constitutes the fifth part of the Civil Code of 10 December 1907.

43 Switzerland is the only European country that has two codifications regulating the various forms of private legal relationships. Other European countries such as France, Germany and Italy have just one code governing the rights and obligations of private individuals.

44 Contrary to Switzerland, these countries also have a separate Commercial Code that deals with specific legal questions relating to trade and commerce.

45 The Code of Obligations has the following five main sections:

General Provisions (Arts 1–183 CO) dealing, in particular, with the creation of obligations arising from contracts (see para. 83), torts (see para. 85) and unjust enrichment (see para. 85), the performance, non-performance and extinguishment of obligations as well as the assignment of a claim and the assumption of a debt;

Specific Contracts (Arts 184–551 CO) containing rules governing certain contractual relationships such as, for example, the contract of sale, the lease contract, the employment contract, the contract for work and services, the simple mandate contract and the simple partnership contract (see paras 565–3106);

Commercial Enterprises and the Cooperative such as the corporation (Arts 530–926 CO);

Commercial Register, Business Names and Commercial Accounting (Arts 927–664 CO); and

Negotiable Securities such as the cheque (Arts 965–1186 CO).

46 The Civil Code contains an Introductory part (Arts 1–10 CC) and four sections with articles pertaining to the Law of Persons (Arts 11–89 CC), Family Law (Arts 90–456 CC), Inheritance Law (Arts 457–640 CC) and Property Law (Arts 641–977 CC).

47 The Civil Code and the Code of Obligations are formally two separate codes with individual sections and numbering. However, the rules contained in the Civil Code also apply to the rules set out in the Code of Obligations. The rules on the civil capacity to act of natural persons (Arts 11–19 CC), the general rules on legal entities (Arts 52–59 CC) and the articles on the acquisition of chattels (Arts 714–729 CC) and real estate (Arts 656–665 CC) are of particular significance for contract law. Likewise, the general provisions of the Code of Obligations also apply to the rules set out in the Civil Code, irrespective of their individual placement in the Code of Obligations (Art. 7 CC).Footnote 1

48 Swiss contract law is more than just the Civil Code and the Code of Obligations. There are a number of other statutes containing rules that are relevant for contractual relationships such as the Federal Act on Insurance Policies of 2 April 1908 (IPA).

II Fundamental Principles of Contract Law

A Freedom of Contract

1 Principle

49 The principle of freedom of contract (Vertragsfreiheit, liberté contractuelle, libertà contrattuale) is an aspect of the broader concept of private autonomy (Privatautonomie, autonomie privée, autonomia privata).Footnote 2 The principle of private autonomy states that the subjects of law are – within the limits of the law – free to govern their own affairs.

50 The principle of private autonomy is derived from Articles 27 and 94 of the Swiss Federal Constitution on economic freedom (Wirtschaftsfreiheit, liberté économique, libertà economica).Footnote 3

51 The principle of freedom of contract encompasses the freedom to enter into a contract and to choose a contractual partner at will (see paras 52–54), the freedom of content (see paras 55–57), the freedom of form (see paras 58–62), and the freedom to modify and to terminate the contract (see paras 63–65).

2 Aspects

a Freedom to Enter into a Contract and to Choose a Partner at Will

52 The first aspect of the principle of freedom of contract is the freedom to conclude a contract. This freedom to enter into a contract means that a party has the (positive) right to enter into a contract at will as well as the (negative) right to desist from entering into a contract.Footnote 4

53 Parties also have the right to choose a contractual partner with whom they wish to enter into a contract.Footnote 5

54 This freedom is restricted (by statute or by contract) if a party is under an obligation to enter into a contract. (Public law) statutes may contain an obligation to enter into a contract. For instance, Article 3 of the Federal Act on Health Insurance of 18 March 1994 (HIA) provides that each person domiciled in Switzerland must be insured for health care in the event of illness. A contractual obligation to enter into a contract can be set out in a preliminary contract (Art. 22 CO; Vorvertrag, promesse de contracter, promessa di contrattare), which is a binding agreement to form a contract at a later date (see paras 890–893).

b Freedom of Content

55 The second aspect of the principle of freedom of contract is the freedom with respect to the content of the contract (Inhaltsfreiheit, liberté du contenu, libertà di definire il contenuto del contratto). Within the limits of the law, the parties are free to determine the content of their contract (Art. 19(1) CO).

56 The limits to this freedom can be found, inter alia, in Article 19(2) CO and, in particular, in Article 20(1) CO, which states that a contract is void if its terms are impossible, unlawful or immoral (see paras 201–211).

57 The principle of freedom of content means that the parties are free to create new types of contracts that are different from the specific contracts contained in the Code of Obligations, that is, innominate contracts (see paras 341, 2879–2915). The contracting parties may also modify and/or combine the contracts contained in the Code of Obligations (see paras 2888–2896).

c Freedom of Form

58 The third aspect of the principle of freedom of contract is the freedom with respect to the form of the contract (Formfreiheit, liberté de la forme, libertà della forma). According to Article 11 CO, the validity of a contract is not subject to compliance with any particular formal requirement unless a particular formal requirement is prescribed by statutory law. This means that contracts only have to respect a certain formal requirement if a statute (Art. 11 CO) or an agreement between the parties (Art. 16 CO; see paras 196–198) requires it.

59 In the absence of such a statutory or contractual prerequisite, the parties can enter into their contract by conclusive actions, orally, in textual form, in writing (Arts 12–15 CO) or by public deed (see para. 185). This is consistent with the principle of consent (Konsensprinzip, principe du consensualisme, principio del consenso) according to which the mere consent of the parties suffices to create at least one obligation.Footnote 6

60 The freedom with respect to the form of the contract means that any modifications to, or the termination of, the contract are not subject to any formal requirements (see Art. 12 CO).

61 If the statutory law or the contract requires the contract to be in a textual form, in writing or executed by public deed, the contract is only validly concluded if all objectively and subjectively essential elements of the contract meet this formal requirement (see Art. 11(1) CO):Footnote 7

The objectively essential elements of a contract (essentialia negotii; objektiv wesentliche Punkte, éléments objectivement essentiels, elementi oggettivamente essenziali) are those elements on which the parties must agree. If the parties are not able to agree on such an element, the contract suffers from a gap which neither the statutory law nor the arbitrator or judge can fill.Footnote 8 The following are objectively essential elements: (1) the identity of the parties bound by the contract and their respective positions (e.g., the contract of sale has to define who is the seller and who is the buyer); (2) the determination (or at least the determinability) of the main obligations to be performed by each party (e.g., the object for sale, the work to be carried out, the services to be rendered, etc.). The financial consideration does not need to be determined, it is sufficient if it is determinable (by statutory law or by contract). With respect to nominate contracts (see para. 340), the main obligations are often determined by the statutory definition of the contract in question (e.g., the object and the price for the contract of sale according to Article 184(1) CO; see paras 584–590). With respect to innominate contracts (see paras 341, 2879–2915), the main obligations have to be determined on the basis of the case law and commercial usages.Footnote 9 In practice, the parties regularly include clauses in their contracts which go well beyond the objectively essential elements.

The subjectively essential elements (subjektiv wesentliche Punkte, éléments subjectivement essentiels, elementi soggettivamente essenziali) are those elements which at least one of the parties considers to be so important that such party does not want to be bound by the contract without agreement on these elements.Footnote 10 Thus, an element is subjectively essential if it is, at least for one of the parties, a conditio sine qua non in order for this party to be bound by the contract.Footnote 11 The party who intends to make the latter’s willingness to be bound by the contract dependent on an agreement on a certain element must make this clear to the other party. Otherwise, the presumption of Article 2(2) CO applies in favour of a contractual agreement.Footnote 12 A party may consider any element of a contract as subjectively essential, for example, the terms of performance, the rules on non-performance, the applicable law, the dispute resolution method, etc.

62 A lack of agreement with respect to an objectively essential element prevents the conclusion of the contract, even if the parties wish to be bound by the contract. On the contrary, a lack of agreement with respect to a subjectively essential element prevents the conclusion of the contract because of the lack of consent of (one of) the parties to be bound.Footnote 13

d Freedom to Modify and to Terminate the Contract

63 The fourth aspect of the principle of freedom of contract is the freedom to modify and terminate the contract.

64 In general, a party can only modify a contract with the consent of the other party. Within certain limits, a contract can also grant to one party the right to unilaterally modify the contract (see paras 402–405). In exceptional circumstances, one party can modify the contract against the will of the other party. This might be possible, for example, if circumstances change after the conclusion of the contract due to an unforeseeable impediment beyond the control of the party wishing to modify the contract. However, the impediment must not be avoidable or be overcome easily, and it must lead to an imbalance between the rights and obligations of the parties (clausula rebus sic stantibus; see paras 395–411). Article 373(2) CO provides for the application of this principle to the contract for work and services (see paras 1598–1634).

65 The parties can always terminate their contract by mutual agreement (actus contrarius).Footnote 14 To the contrary, a party can only unilaterally terminate a contract if the contract or a statute allows it. This is, in particular, the case for contracts of duration (see para. 350) such as the lease contract (Arts 266a–o CO) or the employment contract (Art. 335–c CO) for which the statutory law provides for the right of either party to terminate the contract by a notice of termination (Kündigung; résiliation; disdetta, risoluzione) (see paras 2818–2827). Furthermore, according to case law, each party to a contract of duration has the right to terminate the contract for valid reasons if one cannot reasonably expect from this party to remain bound by the contract.Footnote 15 The parties cannot waive this right in their contract.

3 Mandatory and Optional Statutory Provisions

a Principle

66 The parties enjoy the principle of freedom of contract (see paras 49–70) only ‘within the limits of the law’ (Art. 19(1) CO). A contract with an illegal content is thus null and void (Art. 20(1) CO). The law imposes two kinds of limits on the parties’ freedom of contract.

b Mandatory Provisions

67 The mandatory provisions (zwingende Bestimmung, norme impérative, norma imperativa) are those from which the parties cannot validly derogate.Footnote 16 Such provisions pursue a superior interest which overrides the will of the parties. As a consequence, an arbitrator or judge cannot apply an agreement between the parties which would run counter to a mandatory provision. Given the principle of freedom of contract (see paras 49–70), mandatory provisions are the exception rather than the rule, even though such provisions have become more and more numerous, in particular, in the consumer protection arena (see paras 363–368). Some statutory provisions explicitly state whether they are of a mandatory nature or not (e.g., Arts 100(1), 361–362 CO). Other provisions are considered mandatory even though the statutory law does not expressly characterise them as mandatory (e.g., Art. 404(1) CO; see paras 2402–2408). In some socially sensitive contracts, the statute presumes the mandatory character of the provisions, unless expressly provided by statute (e.g., Arts 273c(1) for the lease contract, 492(4) CO for the surety contract).

68 There are two types of mandatory provisions:

The absolutely (or bilaterally) mandatory provisions (zweiseitig zwingende Bestimmung, norme absolument impérative, norma assolutamente imperativa) are those from which the parties cannot derogate, be it in favour of one or the other party (e.g., Art. 361 CO). The purpose of these norms is to protect a general interest which is deemed to be superior to the interests of the parties; and

The relatively (or unilaterally) mandatory provisions (einseitig zwingende Bestimmung, norme relativement impérative, norma relativamente imperativa) are those from which the parties can derogate only in favour of one party, but not the other party (e.g., Art. 418a(2) CO; see para. 2514). The purpose of these norms is to protect the party which the legislator considers as being the economically weaker one.

c Optional Provisions

69 The optional provisions (dispositive Bestimmung, norme dispositive, norma dispositiva) are those from which the parties can validly derogate. Their role is, above all, to provide the parties with a balanced solution in the event that they have not provided for a contractual provision on a disputed issue. The optional provisions serve as a basis for the arbitrator or judge to fill the gap in the parties’ contract (e.g., Art. 189(1) CO; see para. 663). The optional provisions may also serve to clarify the meaning of the contractual provisions in question (e.g., Art. 189(2) and (3) CO). Certain provisions explicitly state that they are optional (e.g., Art. 364(3) CO: ‘unless otherwise required by agreement’; see paras 1262–1264).

70 There are two types of optional provisions:

Absolutely optional provisions are those from which the parties can validly derogate in any form, even by conclusive actions; and

Relatively optional provisions are those from which the parties can only derogate in writing (e.g., Art. 418g(1) 2nd sentence CO: ‘unless otherwise agreed in writing’; see para. 2514). The legislator wishes to oblige the party (often considered to be the economically weaker one) to think before giving up a protection offered by the statutory law.Footnote 17

B Good Faith

71 ‘Every person must act in good faith in the exercise of his or her rights and in the performance of his or her obligations’ (Art. 2(1) CC). This principle of acting in good faith (Treu und Glauben, bonne foi, buona fede) encompasses (ethical or moral) values such as trust, honesty, loyalty and fairness.

72 The most important application of the principle of acting in good faith in contract law is the objective interpretation of declarations of intent according to the principle of trust (see paras 131–132). Further important applications of the principle of acting in good faith include the pre-contractual duties imposed on negotiating parties (see paras 90–99), ancillary contractual duties (see paras 675, 704), liability for breach of trust (see paras 87–89) as well as the ascertainment of the parties’ hypothetical intent to fill gaps in the parties’ contract.

C Prohibition of an Abuse of Right

73 According to Article 2(2) CC, ‘the manifest abuse of a right is not protected by law’. Where a party has a valid right against another party, the law usually supports the enforcement of such a claim. However, there are exceptional situations where the arbitrator or judge may refuse to assist such a party if the pursuit of the claim is considered to be abusive. In order to be manifestly abusive within the meaning of Article 2(2) CC, the assertion of the rights must be blatantly improper (offenbarer Rechtsmissbrauch, abus manifeste d’un droit, abuso di diritto manifesto). As Article 2(2) CC is a mandatory provision (see paras 67–68),Footnote 18 the arbitrator or judge must determine ex officio whether the parties have abused their rights.

74 The courts have developed groups of cases where the assertion of a right is deemed manifestly abusive within the meaning of Article 2(2) CC. The general prohibition of an abuse of right thus: (1) prohibits contradictory conduct (venire contra factum proprium); (2) prohibits the assertion of a right when one does not have any interest worthy of protection; (3) imposes the duty to exercise one’s rights with moderation; (4) prohibits a dishonest acquisition of rights; (5) prohibits using a legal institution in a way that is contrary to its purpose; and (6) prohibits the assertion of one’s rights when this would lead to a blatant imbalance between the relevant legitimate interests.Footnote 19

D Burden of Proof

75 ‘Unless the law provides otherwise, the burden of proving the existence of an alleged fact lies with the person who derives rights from that fact’ (Art. 8 CC). This fundamental provision on the burden of proof (Beweislast, fardeau de la preuve, onere della prova) provides that if the party who bears the burden of proof fails to prove the alleged facts, such party bears the negative consequences thereof, that is, the dismissal of such party’s claim.

76 The law contains some exceptions to this rule. In the field of contract law, the most important exception is the one found at Article 97(1) CO, which presumes that the debtor was at fault. In this case, it is for the debtor to prove that it was not at fault (see paras 439–443).

III Obligation (as the Effect of the Contract)

A Definition

1 Duty to Fulfil and Right to Claim

77 An obligation (Obligation, obligation, obbligazione) is a legal relationship between two persons (or groups of persons).Footnote 20

78 The term ‘obligation’ encompasses the following two indivisible aspects:

From the perspective of the debtor (Schuldner, débiteur, debitore), the obligation is the duty to fulfil the debtor’s debt (Schuld, dette, debito); and

From the perspective of the creditor (Gläubiger, créancier, creditore), the obligation is the right to demand and receive the debtor’s performance when it is due (Forderung, Forderungsrecht; créance; credito, pretesa). If the debtor does not fulfil the debt, the creditor has the right to enforce the claim with the assistance of the court, respectively the arbitral tribunal, and the enforcement authorities (actionability of the claim).

2 Obligation as an Inter Partes Right

79 An obligation is an inter partes right (relatives Recht, droit relatif, diritto relativo) because it only has effects between the persons that are affected by the obligation through a special relationship. Such a special relationship can, for example, arise out of a contract (see para. 83).

80 The contrary of a relative right is an erga omnes right (absolute right; absolutes Recht, droit absolu, diritto assoluto). An erga omnes right gives the beneficiary the right to dispose of the object and to prevent others from having an influence over that object or right. The right is erga omnes because it can be asserted against anyone. The beneficiary has the right to demand that every person refrains from certain behaviour or tolerates the beneficiary’s behaviour without the need for a special relationship between this person and the beneficiary.

81 There are three types of erga omnes rights:

Personal rights (Persönlichkeitsrecht, droit de la personnalité, diritto della personalità) give the beneficiary absolute protection from unlawful interventions with respect to the latter’s person, in particular life, health, privacy and confidential affairs, personal freedom, honour, economic freedom, photo, name, etc. (Arts 27–30a CC).

Rights in rem (Sachenrecht, droit réel, diritto reale) give the beneficiary the immediate control of physical objects. The most important of the rights in rem is the action in rem for restitution (Art. 641 CC). It encompasses complete control over an object and the unrestricted right to use the object, within the limits of the law; and

Intellectual property rights (Immaterialgüterrecht, droit de la propriété intellectuelle, diritto della proprietà intellettuale) give the beneficiary the immediate control of intangible assets such as copyrights, patents or trademarks.

B Origins of Obligations

1 Principle

82 Any claim, that is, any right which the beneficiary wants to legally enforce, must have at least one legal basis (Rechtsgrund, cause (juridique), causa; causa).Footnote 21 A claim may have several legal bases.

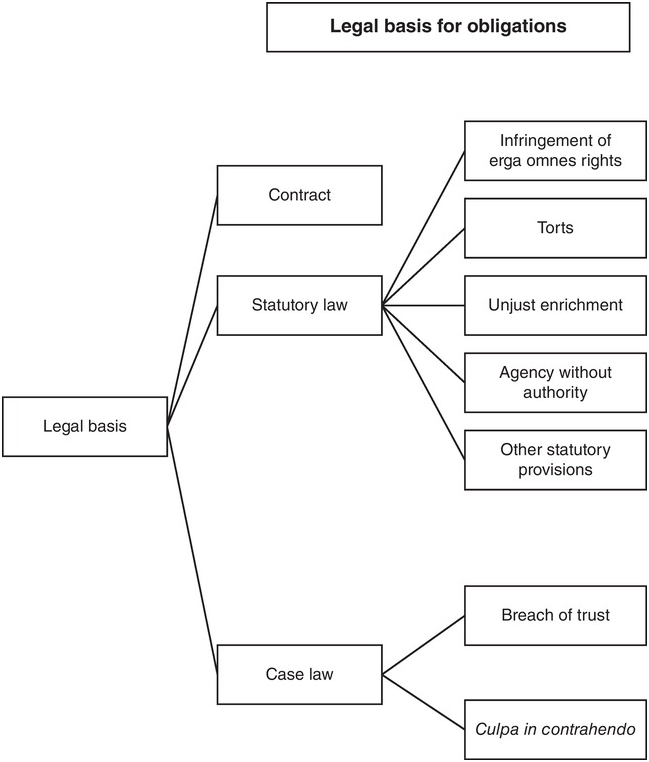

83 An obligation can originate from the parties’ will (voluntary legal basis) or independently of the parties’ will (involuntary legal basis):

The most important voluntary legal basis of an obligation is the contract (Vertrag, contrat, contratto). The obligation comes into existence because two or more persons want it to. This is why the formation of a contract is a bilateral legal act (zweiseitiges Rechtsgeschäft, acte juridique bilateral, atto giuridico bilaterale). For the distinction between unilateral and bilateral contracts, see paras 344–345;

The most significant involuntary legal basis of an obligation is a statute (Gesetz, loi, legge). For the different kinds of obligations arising out of statute, see para. 85;

Some obligations do not have their legal basis in a statute but in case law (Rechtsprechung, jurisprudence, giurisprudenza). Case law has created such obligations based on the special relationship between the parties. For the different kinds of obligations arising out a special relationship, see paras 86–89 (see Figure 3.1).

84

Figure 3.1: Origins of obligations

2 Obligations Created by Statute

85 The following kinds of obligations arise from statute:

Obligations in tort (Arts 41–61 CO; Haftpflicht, ausservertragliche Haftung; responsabilité civile, responsabilité délictuelle, responsabilité extra-contractuelle; responsabilità civile, responsabilità delittuale, responsabilità extra-contrattuale): ‘Any person who unlawfully causes damage to another, whether wilfully or negligently, is obliged to provide compensation’ (Art. 41(1) CO). Article 41(1) CO is the basic statutory provision on liability in tort based on fault. Under Swiss law, there are also various kinds of strict liability;Footnote 22

Obligations arising out of unjust enrichment (Arts 62–67 CO; ungerechtfertigte Bereicherung, enrichissement illégitime, arricchimento indebito): ‘A person who has enriched himself without just cause at the expense of another is obliged to make restitution’ (Art. 62(1) CO). Articles 62–67 CO aim at offsetting transfers of assets without a legal basis (e.g., erroneous payment to someone else’s bank account);

Obligations arising out of agency without authority (Arts 419–424 CO; Geschäftsführung ohne Auftrag, gestion d’affaires sans mandat, gestione d’affari senza mandato): ‘Any person who conducts the business of another without authorisation is obliged to do so in accordance with his best interests and presumed intention’ (Art. 419 CO). ‘The agent is liable for negligence’ (Art. 420(1) CO); and

Further obligations arising from statute: these can be found, in particular, in family law (e.g., the duty of assistance among the members of the family community, Arts 328–330 CC) or inheritance law (e.g., rights of the statutory heirs to the estate, Arts 560–579 CC).

3 Obligations Created by Case Law

86 The courts have created obligations in situations where the parties are in a special relationship (see para. 79), which impose on them a duty to act in good faith (Art. 2(1) CC; see paras 71–72). The most important obligations created by case law are claims for loss arising from pre-contractual liability (see paras 90–99) as well as from a breach of trust (see paras 87–89).

87 The Federal Supreme Court created the liability for breach of trust (Vertrauenshaftung, responsabilité fondée sur la confiance, responsabilità fondata sulla fiducia), in particular, through the Swissair case of 1994Footnote 23 and the Ringier (or Grossen) case in 1995:Footnote 24

In the Swissair case, a company used the logo of the famous parent company Swissair for marketing purposes. In its letters, the company referred to the fact that the logo belonged to the Swissair corporate group. The company went bankrupt and the creditors claimed damages from the parent company Swissair alleging that they only did business with the company because they relied on the guarantee from the parent company Swissair due to the marketing documents. The Federal Supreme Court held that the parent company created a special legal relationship towards the creditors which led to the liability of Swissair.Footnote 25

In the Ringier (or Grossen) case, the Federal Supreme Court awarded damages to an athlete who had been selected by the latter’s federation for the world championship and afterwards prohibited from participating without cause. According to the Federal Supreme Court, the federation’s liability was based on a special relationship created by statute.Footnote 26

88 Subsequently, the Federal Supreme Court has widened the scope of application of the liability for breach of trust to pre-contractual liability (see paras 90–99), liability in tort for advice and information (see para. 1929),Footnote 27 expert liability (see para. 1929)Footnote 28 and liability for legal appearance in the context of bills of exchange.Footnote 29 In recent years, however, decisions of the Federal Supreme Court on liability for breach of trust have become rarer, which is probably also related to the ongoing dogmatic and legal policy concerns of the legal doctrine.

89 According to case law, liability for breach of trust presupposes the following six cumulative conditions: (1) a special relationship between the party causing the loss and the party incurring the loss; (2) trust worthy of protection created by the party causing the loss in the party incurring the loss; (3) impossibility or unacceptability of entering into a contract; (4) breach of trust contrary to good faith; (5) natural and legal causation between the breach of trust and the loss; and (6) fault of the party causing the loss.Footnote 30

IV Formation of Contracts

A Pre-contractual Liability

1 Principle

90 There is no statutory provision on pre-contractual liability (vorvertragliche Haftung, responsabilité précontractuelle, responsabilità precontrattuale; culpa in contrahendo) under Swiss law, contrary to various other legal systems of the Civil law tradition, such as under German (Section 241 (2) BGB), French (Art. 1112 Code civil français (French Civil Code, CCF)) and Italian (Art. 1337 Codice civile italiano (Italian Civil Code, CCI)) law. The Federal Supreme Court recognised pre-contractual liability in a decision of 1951.Footnote 31

91 Common law legal systems, in contrast to Civil law legal systems, are reluctant to impose any duties on the parties during the pre-contractual phase. English courts do not recognise a general doctrine of fault in bargaining, or a general doctrine of good faith negotiations.Footnote 32 Instead, English law uses a mix of Common law and equitable doctrines to protect a negotiating party, such as, in particular, proprietary estoppel, unjust enrichment and misrepresentation.Footnote 33

2 Conditions

a Principle

92 Pre-contractual liability presupposes the following four cumulative conditions:

Loss suffered by the negotiating partner;

Violation of the principle of good faith (in business transactions) (see paras 71–72);

Natural and legal causation between the violation of the principle of good faith (in business transactions) (see para. 438) and the loss suffered by the negotiating partner; and

Fault of the party causing the loss.

b Violation of the Principle of Good Faith (in Business Transactions)

93 Whether there is a violation of the principle of good faith (in business transactions) can only be decided in individual cases on the basis of the specific circumstances. The specific rules of conduct to which a party is bound depend on what a reasonable person in the same situation could expect in good faith from the negotiating partner.Footnote 34 Indeed, anyone who enters into contractual negotiations is subject to the general duty to exercise his or her rights and obligations in good faith (Art. 2 CC; see paras 71–72). This general duty is the basis for various duties of care, protection and consideration, which are concretised in the pre-contractual phase in the form of certain duties of conduct.

94 This includes, in particular, the duty of fair negotiations, according to which parties must negotiate seriously and in accordance with their true intentions (duty to negotiate seriously).Footnote 35 It follows that a person who does not want to conclude a contract (any more) (with the same partner) should not enter into contract negotiations or should break off those already entered into.Footnote 36 Similarly, a party negotiates in bad faith if such party, negligently or intentionally, allows a contract that is formally (see paras 176–198) or substantively (see paras 199–220) null and void to be concluded, even though this party knows or should know that the negotiating partner trusts in the (formal and substantive) validity of the contract.Footnote 37 The same applies to the person who knows or should know that the conclusion of a valid contract is impossible, whether in fact (mistake as to facts, see paras 235–239; initial subjective impossibility of performance; see paras 210–211) or in law (e.g., impossibility of the subject matter of the contract; see paras 208–211).

95 The requirement to negotiate in good faith (Art. 2 CC; see paras 71–72) encompasses various information duties.Footnote 38 A distinction must be made between the duty to inform oneself and the duty to inform the negotiating partner:

In principle, it is assumed that the partners have equally strong negotiating positions and therefore that each must look after their own interests. From this it is deduced that each negotiating partner must also obtain the information such partner considers necessary for the conclusion of the contract;Footnote 39

With respect to the duty to inform the other negotiating partner, a distinction can be made between a general duty to inform and specific duties to inform. The general duty to inform is the duty to inform the negotiating partner spontaneously to a certain extent about (significant) facts which may influence the course of the negotiations, the decision to conclude the contract and the validity of the contract.Footnote 40 The statutory law establishes specific duties of disclosure if it assumes in abstracto that the negotiating parties have unequal opportunities to inform themselves about facts that are important for the conclusion or content of the contract. Such specific (or statutory) duties of disclosure can be found in the statutory law for the conclusion of certain contracts (e.g., Art. 256a CO with respect to the lease contract; Art. 330b CO with respect to the employment contract; Arts 3, 4 IPA with respect to the insurance contract) and in the area of consumer law (e.g., Art. 40d CO, Art. 3(1)(s) Federal Act on Unfair Competition of 19 December 1986 (UCA); see paras 363–368).

96 Similarly, certain duties of care (duties to protect) follow from the requirement to negotiate in good faith (Art. 2 CC; see paras 71–72). This includes, in particular, the duty of each negotiating party to take all protective measures within their own purview so that no (erga omnes) legal interests of the partner are impaired in the course of the negotiations (e.g., the duty to carefully store a sample collection received from the partner).

97 The obligation to negotiate in good faith, on the other hand, does not establish a general duty of confidentiality. If both partners wish the negotiations to be confidential, they can settle this question (and others, such as the exclusivity of the negotiations or the bearing of costs) by means of a negotiation agreement (Verhandlungsvertrag, contrat de négociation, contratto di negoziazione), that is, a non-disclosure or exclusivity agreement.Footnote 41 Otherwise, a negotiating partner can also clearly express the confidential nature of the information given unilaterally. A specific duty of confidentiality may also flow from the nature of the future contract or the circumstances in which a partner receives certain information.

3 Consequences of Pre-contractual Liability

98 If no contract has been concluded due to a culpa in contrahendo, the injured party’s claim is usually for damages. Based on Article 26(1) CO, negative interest damages (see para. 434) are owed.Footnote 42 The injured partner must therefore be placed in the same position as if the contract negotiations had never taken place. This applies, in particular, to (useless) expenses incurred by the negotiating partner in reliance on the conclusion of a contract (e.g., travel expenses, costs for expert opinions, etc.). If pre-contractual obligations are only breached at a later stage of the negotiations, only the expenses incurred after the breach are to be reimbursed.Footnote 43 Exceptionally, in case of gross negligence, positive interest damages (see para. 434) may also be awarded in equity according to Articles 26(2) or 39(2) CO.Footnote 44

99 If a disadvantageous contract has been concluded due to a culpa in contrahendo, certain authors refer the injured party to the rules on unfair advantage (Art. 21 CO) and lack of consent (Arts 23–31 CO; see paras 221–273).Footnote 45 Other authors grant the injured party the right to terminate the disadvantageous contract in whole or in part.Footnote 46 In addition, damages may also be awarded.Footnote 47

B Offer and Acceptance

1 Principle

100 According to Article 1 CO, ‘[t]he conclusion of a contract requires a mutual expression of intent by the parties’.

101 The formation of a contract therefore has the following elements: There must be at least two expressions of intent. This implies, firstly, that each party has developed an (inner) intent (see paras 102–103) and, secondly, that each party declares the intent to the other party (see paras 104–105). The expressions of intent, directed towards the conclusion of a contract, are called the offer and acceptance (see paras 106–121). They have to be exchanged, which means that one party must take notice of the other party’s intent (see paras 122–124). The parties must come to an agreement, that is, they must mutually consent to the contract. Both the offer and the acceptance must therefore have the same content (see paras 127–130).

2 Expression of Intent

102 The offer and acceptance are expressions of intent. The expression of intent (Willensäusserung, Willenserklärung; manifestation de volonté; manifestazione della volontà) is the expression of an intent to establish, amend or terminate an obligation or legal relationship.Footnote 48

103 The expression of intent can be split into the following three sub-elements:

The intent to act (Handlungswille), which is the will of the declarant to perform an act;Footnote 49

The intent to legally bind oneself (Geltungswille), which is the will of the declarant to perform a legal act;Footnote 50 and

The intent to trigger a certain legal consequence (Rechtsfolgewille), which is the will of the declarant to bring about a certain legal consequence.Footnote 51

104 With respect to the formation of a contract, it is not sufficient to have the will to act, the will to legally bind oneself and the will to trigger a certain legal consequence. This (purely internal) intent needs to be communicated to the other party.

105 The communication of the expression of intent may take different forms:

The explicit communication of the expression of intent (ausdrückliche Willensäusserung, manifestation de volonté expresse, manifestazione espressa della volontà) is where the declarant expresses the intention to bring about a certain legal consequence by a socially recognised means of communication or by a means of communication agreed by the parties in the individual case.Footnote 52 These are usually oral or written statements (expressis verbis), that is, statements in the form of spoken or written words. The declarant may also express such intention by other socially recognised signs (e.g., nodding the head, shaking the head, raising the hand during an auction);Footnote 53

The implicit communication of the expression of intent (konkludente Willensäusserung, manifestation de volonté par actes concluants, manifestazione della volontà per atti concludenti) is where the intention of the declarant to bring about a certain legal consequence is not directly expressed in the declaration, but only results indirectly from the behaviour of the declarant or other circumstances;Footnote 54 and

Silence (stillschweigende ‘Äusserung’, manifestation de volonté tacite, manifestazione tacita della volontà) is the ‘expression’ of intent through simple passive silence or doing nothing.Footnote 55 In principle, silence – which is particularly important in practice – is a subcategory of the category of implicit communication. As a general rule, silence or doing nothing does not constitute an intent to bring about a certain legal consequence (see para. 121). Therefore, the rule ‘qui tacet consentire videtur’ (‘qui ne dit mot consent’) only applies within narrow limits (see para. 121).

3 Offer

106 The offer (Antrag; offre; offerta, proposta) is the first expression of intent in which the offeror authorises the offeree to enter into a contract of a specific content with the offeror.Footnote 56 An expression of intent is only an offer if the person declaring the intent has the will to bring about a certain legal consequence (see para. 103), that is, to conclude a contract with a specific content.

107 The offer must be received by the offeree. Therefore, the validity of the offer depends on the addressee receiving the offer (see paras 122–124).

108 With respect to its content, the offer must include all (subjectively and objectively) essential elements (see para. 61) of the future contract.Footnote 57

109 With respect to its form, according to the statutory law, the offer does not have to comply with any specific formal requirements in order to be binding (Art. 11(1) CO; see paras 180–189).

110 The offer triggers the following two consequences:

The offer authorises the offeree to conclude a contract with the content described in the offer by accepting it in accordance with the offer;Footnote 58 and

The offer binds the offeror.Footnote 59

111 The binding effect starts, in principle, when the addressee receives the offer (see paras 122–124).

112 The binding effect is limited in time. Articles 3, 4 and 5 CO serve to determine the duration of the offer’s binding effect:

Offer limited in time: if the offeror limits the offer in time, the offeror is bound by the offer until the time limit expires (Art. 3(1) CO). The offeror can limit the offer in time either by reference to a specific date (Art. 79 CO; e.g., ‘until 3 October 2023’) or a specific period of time (Art. 77 CO; e.g., ‘within eight days’). The time limit can also arise out of the circumstances (‘immediately after your return from England’);

Offer unlimited in time: if the offeror makes the offer without a time limit (which is not recommended), the time during which the offeror is bound by the offer depends on whether the offer was made in the parties’ presence or absence. An offer is made in the parties’ presence (Antrag unter Anwesenden, offre entre presents, proposta fra presenti; Art. 4 CO) if the offeror and the offeree are in direct, immediate communication so that a live exchange between the two is possible.Footnote 60 This is not only the case if the offeror and the offeree are face to face, but also if they are talking on the phone, or are communicating through an instant message program (MMS). An offer is made in the parties’ absence (Antrag unter Abwesenden, offre entre absents, proposta fra assenti; Art. 5 CO) if the offeror and the offeree are communicating through a medium which involves a time lag (letter, e-mail, etc.). In this case, the offer remains binding on the offeror until such time as the latter might expect to receive a duly sent reply (Art. 5(1) CO). The duration of the binding effect corresponds to the usual total duration of the following three periods: (1) the usual duration of the transmission of the offer from the offeror to the offeree; (2) the offeree’s reasonable period of time for consideration; and (3) the usual duration of the transmission of the acceptance from the offeree to the offeror.Footnote 61

113 If the positive reaction by the offeree reaches the offeror too late, it can, in principle, no longer trigger the consequences of an acceptance (see paras 116–121). However, if the acceptance was sent off in time but arrives too late, the offeror must react immediately by declining the acceptance if the offeror does not want to be bound by the original offer (Art. 5(3) CO).

114 An expression of intent without binding effect is not an offer but a (non-binding) invitation to treat (Einladung zur Offertstellung, invitation à faire une offre; invito a fare un’offerta; invitatio ad offerendum).

115 The binding effect of an expression of intent can be excluded in the following three ways:

Exclusion by declaration: The offeror is not bound by the offer if the offeror has made an express declaration to that effect (Antrag ohne Verbindlichkeit, offre sans engagement, proposta senza impegno; Art. 7(1) CO). In trade, clauses such as ‘while stock lasts’, ‘without obligation’ or ‘on a non-binding basis’, etc., are common;

Exclusion by statutory law: According to Article 6a(1) CO, the sending of unsolicited goods does not constitute an offer. The recipient can freely dispose of the goods. The recipient is not obliged to keep or return such goods (Art. 6a(2) CO). However, where unsolicited goods have obviously been sent in error, the recipient must inform the sender. Furthermore, according to Article 7(2) CO, the sending of tariffs, price lists and the like does not constitute an offer. By contrast, the display of merchandise with an indication of the price does generally constitute a (binding) offer (Art. 7(3) CO). According to Articles 3(1) and 7–9 of the Ordinance on Price Indication of 11 December 1978 (OPI), store owners must put clear and easily readable prices on their products if they offer these products to consumers or if they advertise their products (Art. 2(1)(a) and (d) IPO);

Exclusion deriving from the circumstances: An expression of intent in view of the establishment of a relationship arising from an act of kindness (Gefälligkeitsverhältnis, rapport de complaisance, rapporto di cortesia) does not have any (legally) binding effect (see paras 1924–1929). Therefore, the relationship arising from an act of kindness does not give rise to any legal obligation to perform the promised act of kindness.Footnote 62

4 Acceptance

116 The acceptance (Annahme, acceptation, accettazione) is the second expression of intent by which the offeree, that is, the addressee of the offer (see para. 107), concludes a contract with the offeror with the content specified in the offer.Footnote 63 By the acceptance, the acceptor agrees to conclude a contract with the content described in the offer (see Art. 1118(1) CCF).

117 Like the offer (see para. 106), the acceptance must be received by the offeror. Therefore, the validity of the acceptance depends on the addressee receiving the acceptance (see paras 122–124).

118 The content of the acceptance is determined by the content of the offer (see para. 108). The offeree’s will to conclude a contract must be congruent in terms of content with the objective (see para. 61) and (for the offeror, subjective; see para. 61) essential elements of the contract.Footnote 64 According to Article 2(1) CO, where the parties have agreed on all essential elements, it is presumed that the contract will be binding, notwithstanding any reservations as regards non-essential elements. In the event of a failure to reach an agreement on such non-essential elements after the contract is concluded, the arbitrator or judge must determine them with due regard to the nature of the transaction (Art. 2(2) CO).

119 If the content of the recipient’s expression of intent differs from the offer due to amendments or additions regarding essential elements (see para. 61), there is no acceptance within the meaning of Article 3 CO. If such an expression of intent, which differs from the offer with respect to essential elements, expresses the intent of the recipient to conclude a contract (see para. 102), there is a counter-offer (Gegenantrag, Gegenofferte; contre-offre; controfferta), which, in turn, can be accepted by the original offeror.Footnote 65

120 According to the statutory law, the acceptance, like the offer (see para. 109), is not subject to any particular formal requirement (Art. 11(1) CO; see paras 180–189).

121 Silence or doing nothing (see para. 105) is generally not considered to be an acceptance (Art. 6 CO). However, a contract is concluded despite the offeree remaining silent or doing nothing in reaction to the offer, if this was to be expected because of ‘the particular nature of the transaction or the circumstances’ (Art. 6 CO). There are a series of typical circumstances in which the offeror may and must infer the offeree’s will to accept the offer: (1) when the parties to the negotiation agreed that the silence of the offeree in reaction to the future offer would constitute an acceptance; (2) when the offeror unilaterally waives an express acceptance; (3) when the offeree previously expressed the will to conclude the contract; (4) when there exists an ongoing business relationship between the negotiating parties; and (5) when the contract negotiations have reached such a stage that their favourable outcome is practically fixed.Footnote 66 Article 395 CO sets out specific rules regarding the conclusion of the simple mandate contract (see paras 1937–1951).

5 Receipt of the Offer and Acceptance

122 Both the offer (see para. 106) and acceptance (see para. 116) are expressions of intent that must be received by the addressee in order to deploy any legal effect (empfangsbedürftige Willensäusserung, manifestation de volonté sujette à réception, manifestazione della volontà soggetta a ricezione; see Section 130 BGB). Receipt (Empfang, Abnahme, Zugang; réception;, ricevimento) is the entry of the expression of intent into the sphere of influence of the addressee.Footnote 67

123 The exact point in time in which the expression of intent is received is important for questions such as the following: From what point in time is a person bound by the declaration made (see para. 111)? At what point in time is the contract concluded (see para. 126)? Can the expression of intent be withdrawn (see para. 125)?

124 The principle of receipt (‘mailbox theory’; Empfangstheorie, Zugangstheorie; théorie de la réception;, teoria dell’atto ricettizio)Footnote 68 has the following two core elements:

The expression of intent must have entered into the addressee’s sphere of influence (Einflussbereich, Machtbereich; sphère d’influence; sfera d’influenza). The addressee’s sphere of influence includes not only the latter’s home, business premises and mailbox, but also the latter’s post office box, answering machine, fax machine and e-mail server, electronic mailbox or wall in a social media service (Linkedin, etc.); and

Whether and when the addressee actually takes note of the expression of intent is irrelevant. This means that the expression of intent must be brought to the attention of the addressee in such a way that, under normal circumstances, the addressee can be expected to take note of it.Footnote 69

6 Withdrawal of Offer and Acceptance

125 Both the offer (see paras 106–115) and acceptance (see paras 116–121) can be withdrawn under certain conditions (Art. 9 CO): if the offer or acceptance and the corresponding withdrawal are received simultaneously, or if the corresponding withdrawal overtakes the offer or the acceptance, the relevant offer or acceptance is considered revoked.

7 Time of Conclusion of the Contract

126 Timewise, the contract is concluded when the acceptance enters the offeror’s sphere of influence, pursuant to the principle of receipt (see para. 124).

8 Congruency of Offer and Acceptance

127 The contract is only concluded if the offer (see paras 106–115) and acceptance (see paras 116–121) are congruent with respect to their content (Art. 1(1) CO).

128 If the offer and acceptance are congruent, there exists a consensus (Konsens, accord, consenso) between the parties and the contract is concluded with the content corresponding to the parties’ common intent.

129 If the offer and acceptance are incongruent, there exists a disagreement (Dissens, désaccord, dissenso) between the parties:

If the parties are aware of this fact, there exists an open disgreement (offener Dissens; désaccord patent, dissentiment manifeste; dissenso palese) between themFootnote 70 and the contract is not concluded;

If the parties are not aware of this fact, there exists a hidden disagreement (versteckter Dissens; désaccord latent; dissentiment inconscient, dissenso occulto). This is, in particular, the case when the offer and acceptance are formally congruent, but each party understands them differently.Footnote 71

9 Interpretation of Expressions of Intent

131 The interpretation (Auslegung, Interpretation; interprétation, interpretazione) of expressions of intent aims at determining the content of the expression of intent insofar as this content is in dispute between the parties.Footnote 72

132 Based on Article 18 CO, the Federal Supreme Court has developed the following procedure in order to determine whether the parties’ respective expressions of intent are congruent (see paras 127–130) and, thus, whether the contract has been concluded:

First, the actual will of the person expressing the intent (i.e., the declarant) needs to be determined (subjective or empirical interpretation; subjektive Auslegung, empirische Auslegung; interprétation subjective, interprétation empirique; interpretazione soggettiva, interpretazione empirica).Footnote 73 If the recipient understands this actual will in the same way as the declarant intended it, this shared understanding is decisive, irrespective of whether the declarant expressed the intent properly. This is because according to Article 18(1) CO, the actual intent of the parties is decisive, not any false expressions of such intent. If the interpretation leads to the result that both parties wanted the same thing, it is called an actual (or natural) consensus (tatsächlicher Konsens, accord de fait, consenso di fatto; see para. 128). According to the Federal Supreme Court, the parties’ will and knowledge is a question of fact which it does not, in principle, review on appeal (Art. 105(1) of the Federal Act on the Federal Supreme Court of 17 June 2005 (FSCA));Footnote 74

Second, if the recipient misunderstands the declarant (i.e., the recipient does not understand the actual intent of the declarant), the question arises whether the understanding of the declarant or the recipient’s one should prevail. The intent must thus be objectively or normatively determined (objektive Auslegung, normative Auslegung; interprétation objective, interprétation normative; interpretazione oggettiva).Footnote 75 The basis for this interpretation is the principle of trust (Vertrauensprinzip, principe de la confiance, principio dell’affidamento). According to this principle, the arbitrator or judge determines how the recipient could and should, in good faith (Art. 2 CC; see paras 71–72), have understood the intent of the declarant under the circumstances.Footnote 76 In the context of the conclusion of the contract, the arbitrator or judge thus determines how each party could and should, in good faith, have understood the other party’s expression of intent under the circumstances and to what extent these (normative) understandings are congruent (see para. 127). To the extent they are congruent, there exists a normative (or legal) consensus (normativer Konsens, accord de droit, consenso normativo; see para. 128). The Federal Supreme Court reviews this objective interpretation on appeal as a question of law. The Court, however, is bound by the factual determinations made by the Cantonal court with respect to the external circumstances of the parties’ will and knowledge (Art. 105(1) FSCA).Footnote 77

V Interpreting Contracts

A Purpose

133 The interpretation (Auslegung, Interpretation; interprétation; interpretazione) of contracts aims at determining the content of the contract insofar as this content is in dispute between the parties.Footnote 78 Each of the expressions of intent (offer and acceptance) must be interpreted to determine the actual (see para. 132) or normative (see para. 132) intent of the parties.

B Means of Interpretation

134 Means of interpretation (Auslegungsmittel, moyen d’interprétation, mezzo di interpretazione) are sources of knowledge for the arbitrator or judge when interpreting a contract.Footnote 79 The Federal Supreme Court has recognised the following seven means of interpretation.

1 Wording of the Contract

135 The starting point of any interpretation is the wording of the contract (literal interpretation).Footnote 80

136 It is assumed that the parties understood the words they used in accordance with the common usage (allgemeiner Sprachgebrauch; sens courant, sens habituel; linguaggio comune) at the time of the conclusion of the contract.Footnote 81

137 If a word has a specific technical meaning in a trade or in a professional circle (Fachausdruck, sens technique spécifique, termine specifico) and all contracting parties belong to this specialist circle, this specific meaning takes precedence over the general understanding of the word (see para. 136).Footnote 82

138 The fact that the parties use specific legal terms is only decisive if the parties are business people who may be presumed to have a certain familiarity with legal terminologyFootnote 83 or if the parties have been advised by persons with legal expertise.Footnote 84

139 The parties may also understand a term in a certain sense which deviates from common usage (see para. 136).Footnote 85 They can formally exercise this liberty by explicitly defining the individual meaning of this term in their contract (definition clauses).

2 All Relevant Circumstances

140 Contracts are to be interpreted in the light of the relevant circumstances (relevante Begleitumstände, circonstances relevantes, circonstanze rilevanti) in which they were concluded.Footnote 86 All accompanying circumstances that have an influence on how a reasonable person could and should, in good faith (Art. 2 CC; see paras 71–72) have understood the contract (or the expression of intent of another person; see para. 102) must be considered (background factual matrix).

141 The persons involved in the contract negotiations must have known these circumstances, or at least been aware of them.

3 Context

142 The individual expression or sentence is usually part of the contract as a whole and thus should be interpreted in its systematic context (systematic interpretation).

143 Context such as the sentence structure, the structure of the contractual document, the relationship to other documents exchanged, etc., must thus be considered.Footnote 87

4 History and Genesis of the Contract

144 The contract is usually the result of a certain development (historical interpretation).

145 The history of the contract includes the previous relationships between the parties, in particular, previous contractsFootnote 88 as well as practices and customs existing between the parties.Footnote 89

146 The genesis of the contract concerns, in particular, the entire conduct of the parties directly before and during the conclusion of the contract.Footnote 90 In particular, the statements exchanged during the contract negotiations,Footnote 91 draft contracts, minutes of meetings,Footnote 92 etc., are important for the interpretation. In addition, the other conduct of the parties before and at the timeFootnote 93 of the conclusion of the contract is important (with respect to the parties’ conduct after the conclusion of the contract, see paras 156–158).

147 Sometimes contracts contain an entire agreement clause (merger clause; Ausschliesslichkeitsklausel, Integrationsklausel; clause d’intégralité; clausula di integralità) by which the parties stipulate that the contract reflects all the points of their agreement and that all previous written or oral agreements are not part of their contract.Footnote 94 However, as a contractual clause, the entire agreement clause is also open to interpretation. The arbitrator or judge is generally bound by such a clause if the parties have negotiated it individually (see para. 319).Footnote 95 However, an entire agreement clause only reinforces the presumption, which applies anyway, that the contract expresses all (important) aspects of the agreement between the parties.Footnote 96

148 The Common law approach to this issue is not uniform. Whereas US law provides for a similar rule (Restatement Second of Contracts, Section 214),Footnote 97 English law has a diametrically opposed approach to the parties’ behaviour prior to the conclusion of the contract.Footnote 98 However, the differences between English and continental European law should not be overstated. On the one hand, the exceptions to the principle, in particular, the special meaning exception, the estoppel by convention exception and the rectification exception,Footnote 99 are so significant that they call into question the principle that pre-contractual conduct cannot be taken into account.Footnote 100 On the other hand, parties often raise arguments relating to the interpretation and rectification of the contract at the same time, with the result that the courts of first instance cannot disregard the history and genesis of the contract.Footnote 101

5 Parties’ Interests and Purpose of the Contract

149 The contract must also be understood in light of the parties’ respective interests and the purpose they were pursuing by its conclusion (teleological interpretation).

150 The parties’ interests (Interessenlage, intérêts respectifs des parties, interessi delle parti) include the reasons and expectations which have led each party to conclude the contract.Footnote 102

151 The purpose of the contract (Vertragszweck, but du contrat, scopo del contratto) pursued by the parties is also important.Footnote 103

152 The parties often declare their mutual interests and/or the purpose of the contract explicitly at the beginning of the contract, in the preamble or in the recitals (Präambel, préambule, preambolo).Footnote 104 If this is not the case, these means of interpretation must in turn first be determined by interpretation.Footnote 105

153 In English law, the parties’ interests and the purpose of the contract are also taken into account in the interpretation of the contract as ‘original assumptions’.Footnote 106

6 Trade Usages

154 Trade usages (Verkehrsübung, usage commercial, uso commerciale) are also a means of interpretation. The expressions used (see paras 135–139) and the conduct adopted by the parties (see paras 156–158) may and must, as a rule, be understood in the sense that they have in accordance with the trade usages of the industry in question.

155 The INCOTERMS (International Commercial Terms 2020) published by the ICC in Paris (see paras 958–959)Footnote 107 and the Uniform Customs and Practices for Documentary Credits (UCP 600 ) are examples of such trade usages.

7 Parties’ Conduct after the Conclusion of the Contract

156 According to the Federal Supreme Court, the parties’ conduct after the conclusion of the contract can only be considered when carrying out a subjective interpretation (see para. 132). With respect to the objective interpretation (see para. 132), the parties’ subsequent conduct is of no importance.Footnote 108

157 However, there is no convincing reason why the subsequent conduct of the parties should not also form an element of the circumstances in the context of an objective interpretation and thus also be used for the interpretation.Footnote 109 The purpose of interpretation, whether subjective (see para. 132) or objective (see para. 132), is indeed to determine what reasonable parties acting under the circumstances at the time of the conclusion of the contract would have expressed and consequently intended by the use of their words or by their other conduct (see para. 132).

158 Other legal systems, such as the ItalianFootnote 110 and SpanishFootnote 111 legal systems explicitly recognise the parties’ subsequent conduct as a means of interpretation. English law, on the other hand, takes a restrictive stance and generally does not consider the parties’ post-formation conduct as a means of interpretation.Footnote 112 However, there are exceptions to this principal stance when (1) it can be proven that the parties have specifically agreed to subsequently amend or terminate the contract;Footnote 113 and (2) in cases of estoppel by convention (see para. 148).

C Maxims of Interpretation

159 Maxims of interpretation are general principles according to which the interpretation must be carried out.Footnote 114 The Federal Supreme Court has recognised the following seven maxims of interpretation.

1 Necessity of Interpretation

160 Even a seemingly clear wording of an expression of intent or a contractual provision requires interpretation in order to ascertain its meaning. Therefore, the wording alone may never be considered decisive.Footnote 115 Swiss law therefore rejects any plain meaning rule (Eindeutigkeitsregel, théorie de l’acte clair, interpretazione basata sul chiaro senso del testo). The means of interpretation (see paras 134–158), for example, the context of the contract (see paras 142–143) or the purpose of the contract pursued by the parties (see paras 149–153), may in fact lead to the conclusion that a contractual provision does not correctly express the meaning of the parties’ agreement.

161 The rule that the interpretation must not stick to the literal sense of the words used (Buchstabenauslegung; interprétation littérale, au pied de la letter; interpretazione letterale)Footnote 116 is also found in other legal systems, such as under German,Footnote 117 Austrian,Footnote 118 FrenchFootnote 119 and ItalianFootnote 120 law, as well as in European harmonisation projects such as the Principles of European Contract Law (PECL)Footnote 121 and the Draft Common Frame of Reference (DCFR).Footnote 122 Spanish lawFootnote 123 expressly provides for the plain meaning rule. In English law, there seems to be no actual plain meaning rule. The case law sometimes emphasises that the court should primarily give effect to the ‘clear and unambiguous language’ of a contractual provision.Footnote 124 The clearer the ‘natural meaning’ of an expression, the less easily the court should depart from it. Other decisions, on the other hand, emphasise that the interpretation must go beyond the natural meaning of the expression and seek other possible understandings based on the circumstances of the transaction in question.Footnote 125

2 Priority of Clear Wording

162 According to the case law of the Federal Supreme Court, the clear wording enjoys priority over other means of interpretation.Footnote 126 If the other means of interpretation do not lead with certainty to a different result of interpretation, the wording shall prevail.

3 Interpretation in Accordance with Good Faith

163 Under an objective interpretation (see para. 132), contracts (and expressions of intent) must be interpreted in accordance with the principle of good faith (Art. 2 CC; see paras 71–72). This includes, in particular, the principle of trust (see para. 132).

164 The assumption underlying the interpretation of the contract that the parties intended an appropriate solution is also based on the principle of good faith (Art. 2 CC; see paras 71–72).Footnote 127 If, however, the interpretation shows that the parties wanted a solution, in that specific individual case, which appears to the arbitrator or judge to be unreasonable, the arbitrators or judges may not substitute their own values for those of the parties.Footnote 128

4 Contract Conclusion as the Relevant Point in Time

165 Within the framework of objective interpretation (see para. 132), the arbitrator or judge determines, with the help of the various means of interpretation (see paras 134–158), how the parties could, and should, have understood their contract at the time of its conclusion.

166 The contract must thus be interpreted ‘ex tunc’, which means that the arbitrator or judge must mentally go back to the time of the conclusion of the contract and ask how the parties could and should have understood their mutual expressions of intent and the resulting contract at that time in view of all the accompanying circumstances known to them (see paras 140–141).Footnote 129

5 Interpretation as a Whole

167 It follows from a systematic interpretation (see paras 142–143) that the individual contractual provision is to be interpreted in the overall context in which it stands.Footnote 130

168 Conflicting provisions within a contract are therefore to be interpreted in a ‘harmonising’ manner as far as possible, so that they have an appropriate meaning as a whole. If different meanings of a contractual provision are justifiable, the meaning that does not contradict any other contractual provision and thus gives the contract as a whole an appropriate meaning shall prevail.Footnote 131

6 Contra Proferentem Rule

169 According to the contra proferentem rule (Unklarheitsregel, règle des clauses ambiguës, regola in case di dubbio), ambiguities in a contract are to be interpreted in case of doubt to the detriment of the author of the contractual text (in dubio contra stipulatorem, in dubio contra proferentem). If the arbitrator or judge finds that there are two possible interpretations of a contractual provision (ambiguity), such arbitrator or judge must prefer the one that is less favourable to the author of the provision.Footnote 132

170 Under Swiss law, the contra proferentem rule only applies when the following three cumulative conditions are met:

The means of interpretation (see paras 134–158) do not lead to a clear result. It is therefore not sufficient that the parties disagree on the interpretation (see para. 133). Rather, it is necessary that several meanings are seriously arguable and the means of interpretation fail, with the result that the existing doubt (‘in dubio’) between the different meanings can only be resolved with the help of the contra proferentem rule;Footnote 133

The ambiguous part of the contract (clause or section) was drafted exclusively by one party;Footnote 134 and

Of the two (or more) meanings, one is less favourable to the drafter of the contract text.

171 In practice, the contra proferentem rule is mainly used for the interpretation of General Terms and Conditions (GTCs), especially in the insurance sector (in dubio contra assecuratorem).Footnote 135 Case law has not yet clearly stated whether the scope of application of the contra proferentem rule should be limited to GTCs or not.Footnote 136

172 This maxim of interpretation, which originates from Roman law, is widely recognised in comparative law. It is generally known in French,Footnote 137 SpanishFootnote 138 and AustrianFootnote 139 law, whereas in GermanFootnote 140 and ItalianFootnote 141 law, it is limited to the interpretation of GTCs. English law also recognises the contra proferentem rule, namely, in connection with exclusion or exemption clausesFootnote 142 and unfair terms in consumer contracts.Footnote 143 The rule has also found its way into the European GTC Directive,Footnote 144 which has been implemented in all EU Member States. International and European harmonisation projects such as the Unidroit Principles of International Commercial Contracts (2016) (PICC),Footnote 145 the PECLFootnote 146 and the DCFRFootnote 147 also include this rule.

7 Other Interpretation Maxims in Cases of Ambiguity

173 The contra proferentem rule (see paras 169–172) is the most important maxim for deciding cases of ambiguity. In addition, there are a number of other maxims that can be employed in cases of ambiguity, namely the following:

Favor negotii: Among several reasonable interpretations of a contractual provision, in case of doubt, the one which ensures its validity is to be preferred (vertragserhaltende Auslegung, effet utile, interpretazione volta a salvaguardare l’efficacia del contratto).Footnote 148 Comparatively, German,Footnote 149 French,Footnote 150 Italian,Footnote 151 SpanishFootnote 152 and English lawFootnote 153 as well as the Common European Sales Law (CESL),Footnote 154 the PICC,Footnote 155 the PECLFootnote 156 and the DCFRFootnote 157 also include this rule of interpretation;

Interpretation in conformity with the non-mandatory provisions of statutory law: Among several reasonable interpretations of a contractual provision, in case of doubt, the interpretation which is in conformity with the non-mandatory provisions of statutory law (see paras 69–70) is to be preferred. Non-mandatory statutory law usually provides for a solution that balances the interests of both parties.Footnote 158 Anyone who wishes to deviate from the non-mandatory law must therefore express this with sufficient clarity;Footnote 159 and

Restrictive interpretation of clauses deviating from non-mandatory statutory law: It follows from the interpretation in conformity with the non-mandatory statutory law that provisions which deviate from the non-mandatory law are to be interpreted restrictively in case of doubt.Footnote 160 Therefore, notably waivers (Verzichtserklärung, déclaration de renonciation, dichiarazione di rinuncia),Footnote 161 exclusion clauses (Freizeichnungsklausel, clause exclusive de responsabilité, clausola esclusiva di risponsabilità; see paras 473–479)Footnote 162 and statements of receipt in full and final settlement (Saldoquittung, quittance pour solde de compte, ricevuta a saldo; see paras 3069–3070)Footnote 163 are to be interpreted restrictively.

VI Validity of Contracts

A Principle

174 If a contract was formed according to the principles described above (see paras 101–173), that is, if the parties have agreed on the (objectively and subjectively) essential elements (see para. 61), one has to verify whether the contract is valid. The following two aspects have to be examined:

First, whether there are statutory rules regarding the form of the contract, and if so, whether the contract respects these rules (see paras 176–198); and

Second, whether the content of the contract is impossible, unlawful or immoral (see paras 199–220).

175 Contracts that violate the relevant formal requirements are null and void (see paras 190–195). The same holds true for contracts with an impossible, unlawful or immoral content (see paras 216–220).

B Validity with Respect to Form

1 Principle of Freedom of Form

176 The principle of freedom of form (Formfreiheit, liberté de la forme, libertà della forma) provides that the validity of legal transactions (Rechtsgeschäft, acte juridique, atto giuridico) does not depend on their form.Footnote 164 This means that, in principle, contracts can be formed orally, by conclusive actions or – in certain circumstances – even by doing nothing (see para. 121).

177 The principle of freedom of form means that the contract is, in principle, already concluded when the substantive requirements for its conclusion (see paras 100–132) are fulfilled, without any additional formal requirements having to be met. Since these substantive requirements essentially consist of the ‘meeting of the minds’ between the contracting parties (see paras 127–130), the principle of freedom of form is sometimes also referred to as the principle of consent (Konsensprinzip, principe du consensualisme, principio del consenso; see para. 59).

178 Article 11 CO expresses the principle of freedom of form as follows: ‘(1) The validity of a contract is not subject to compliance with any particular form unless a particular form is prescribed by law. (2) In the absence of any provision to the contrary on the significance and effect of formal requirements prescribed by law, the contract is valid only if such requirements are satisfied.’

179 Freedom of form is one aspect of the freedom of contract (Vertragsfreiheit, liberté contractuelle, libertà contrattuale; see para. 49).

2 Statutory Formal Requirements

a Purpose of Formal Requirements

180 The legislator regularly pursues a specific policy purpose when it restricts the principle of freedom of form (see paras 58–62), which has nothing directly to do with the latter.Footnote 165

181 Statutory formal requirements pursue the following purposes:Footnote 166

Clarification and preservation of evidence;

Protecting the parties from making rash decisions, in particular, against carelessly entering into a contract;

Legal certainty, not only between the parties to the contract but also towards third parties;

Facilitating the keeping of registers, in particular, in the case of real estate transactions (land register) and in connection with company law (commercial register); and/or

Consumer information, in order to protect the weaker party (see paras 363–368).

b Types of Formal Requirements

182 There are the following four types of statutory formal requirements:

Simple written form (see para. 183);

Qualified written form (see para. 184);

Public deed (see para. 185); and

Text form (see para. 186).

183 Simple written form: A contract in simple written form (einfache Schriftlichkeit, forme écrite simple, forma scritta semplice) must fulfil the following two conditions:Footnote 167

A declaration in written form: The expression of intent is recorded permanently on a physical object (e.g., paper) in characters (Art. 13(1) CO).Footnote 168 The different expressions must not all be on one single document; and

Signature:Footnote 169 The signature (Unterschrift, signature, firma) has the following two functions: (1) The declarant expresses the intent to make a declaration with the aid of the physical object, the content of which corresponds to the content of the physical object;Footnote 170 and (2) since the signature designates the declarant, it serves to identify the person making the declaration with the content of the expression of intent.Footnote 171 In general, a signature with a written last name is sufficient. According to Article 14(1) CO, the signature must be handwritten. However, an authenticated electronic signature combined with an authenticated time stamp within the meaning of the Federal Act on Certification Services in Relation to Electronic Signatures of 19 December 2003 (ESigA) is deemed equivalent to a handwritten signature, subject to any statutory or contractual provisions to the contrary (Art. 14(2bis) CO). The Federal Supreme Court has not yet clearly decided the question of whether an expression of intent transmitted by fax meets the simple written form requirement.Footnote 172 It appears, however, to approve the authors who recognise the fax as a simple written form.Footnote 173 An e-mail, a text message, or MMS, etc., is only sufficient for the simple written form if it fulfils the conditions for an authenticated electronic signature. This means that in the vast majority of cases, a contract requiring the simple written form cannot be concluded via e-mail. However (only) the declaration of the party on which the contract imposes obligations must be in written form (Art. 13(1) CO). Therefore, in a unilateral contract (see para. 344) such as the contract of donation (Arts 239–252 CO), only the promise of the person making the donation must adhere to the simple written requirement (Art. 243(1) CO). The acceptance of the person receiving the donation is not subject to any formal requirement.

184 Qualified written form: A written formal requirement is qualified (qualifizierte Schriftlichkeit, forme écrite qualifiée, forma scritta qualificata) if further (substantive or formal) requirements (in comparison to the simple written form; see para. 183) are added by statute.Footnote 174 For instance, the non-competition clause at the expense of the agent must have a certain content in order to fulfil the simple written formal requirement (Art. 418d(2) CO in connection with Art. 340 et seq. CO; see paras 2636–2658). Similarly, if the guarantor is a natural person and the liability under the contract of surety does not exceed the sum of CHF 2,000, the guarantor has to indicate the amount for which the guarantor is liable in the latter’s own hand in the contract of surety (Art. 493(2) CO).