Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- List of Illustrations

- Note on Transliteration

- Introduction: Material Culture and Mysticism in the Persianate World

- Part I

- Part II

- Conclusion

- Appendix A List of Khamsa Silks

- Appendix B Summary of ‘Shirin and Khusrau’ by Amir Khusrau Dihlavi

- Appendix C Summary of ‘Majnun and Layla’ by Amir Khusrau Dihlavi

- Glossary of Textile Terms

- Glossary of Persian and Arabic Terms

- List of Historic Figures

- Index

5 - Mughal Dress and Spirituality: The Age of Sufi Kings

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 19 April 2023

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- List of Illustrations

- Note on Transliteration

- Introduction: Material Culture and Mysticism in the Persianate World

- Part I

- Part II

- Conclusion

- Appendix A List of Khamsa Silks

- Appendix B Summary of ‘Shirin and Khusrau’ by Amir Khusrau Dihlavi

- Appendix C Summary of ‘Majnun and Layla’ by Amir Khusrau Dihlavi

- Glossary of Textile Terms

- Glossary of Persian and Arabic Terms

- List of Historic Figures

- Index

Summary

Abstract

Mughal kingship is discussed as temporal and spiritual power derived from genealogical and political connections with Sufi groups, who migrated to India and popularized Persian culture and literature, including Khamsa poetry. Figural silks from Safavid Iran are analyzed as the inspiration for those made in the royal workshops of the Mughals, who fashion themselves after Iranian kings. Sufi naqshbandan (‘textile designers’) travelled to India seeking patronage and spiritual freedom and, becoming absorbed into the Mughal atelier, transferred their silk design and weaving skills to indigenous craftsmen. Emperors Akbar (r. 1556-1605) and Jahangir (r. 1605-1627) established cosmopolitan courts that emphasized their ties with Sufi leaders, while exploring other faiths. The use of figural silks at the Mughal court brings patronage of the Khamsa silks into consideration.

Keywords: Mughal silk velvet, Mughal khil‘at , Layla Majnun silk, Ghiyath al-Din, Mughal jama, Shah Jahan

Among the ruling classes in the Persianate world, what appears as a contradiction to the postmodern mind was a perfectly acceptable early modern concept: to be a humble Sufi and a powerful king simultaneously. Striving to be leaders who set an example for subjects in their respective realms, Mughal and Safavid rulers presented an image that aligned them with the chivalric heroes upon whom futuwwat/ javanmardi traditions were based. Throughout the Islamic world, the level of humility expressed by the ruler was dependent on his attire: the pious wore loose-fitting garments made from austere fabrics and patterns, while the more ostentatious metal-ground silks were donned by those who were known as being less observant. The piety of the ruler was therefore expressed through dress, and fashions at court could garner approval or disapproval from local populations.

These beliefs were compounded in Mughal India, where local Hindu populations also examined the projected persona of the ruler in the context of their own relationships with cloth, in which material was a representation of social order and spiritual purity in practice. Sufi groups in South Asia also held sway over much of the population, and the connection with these groups was critical to upholding the authority of the ruling dynasty. Therefore, the appearance of the ruler was critical to legitimizing the claim to sovereignty.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

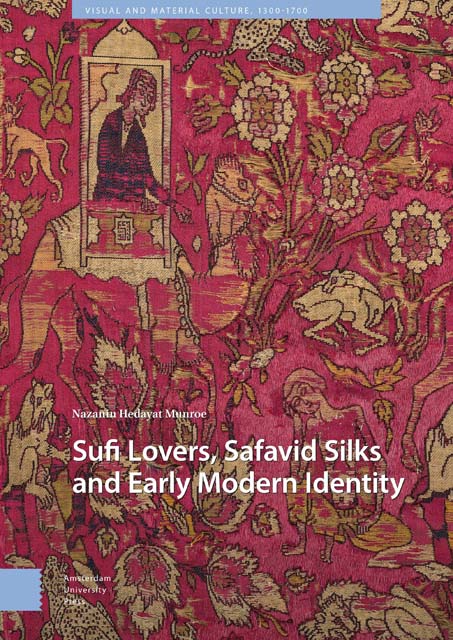

- Sufi Lovers, Safavid Silks and Early Modern Identity , pp. 145 - 180Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2023