There is no pleasure greater than to hear in the street … two neighbors conversing.

Ah, my dear old Ouvidor Street! … How I envy you! Now, in the quietude of your retirement and in the placid and smiling tranquility of your reminiscences, one forgets your iniquities and remembers only past glories.

Place yourself figuratively in the shoes of Henriqueta, an unmarried woman and resident of Rio de Janeiro. I say figuratively because Henriqueta, who was born free in Angola in about 1825, is a slave in Brazil in 1870 and, hence, does not wear shoes. In nineteenth-century Rio, which had more free persons of African descent than it did slaves, the unshod condition of one’s feet, more than the color of one’s skin, was the chief indicator of slave status. In the second quarter of the century, slaves made up almost half of the city’s population. By 1872, that proportion had fallen to 18 percent; however, there were still 48,938 slaves enumerated in the city, maybe as many as had ever lived there.Footnote 3 Without shoes, Henriqueta and those who shared her status knew Rio de Janeiro’s streets, the squares and the alleys, the cobbles and the mud, more intimately, with the soles of their feet, than did the shod and the free. Without freedom, the street, a space that embraced all with little discrimination, offered Henriqueta and others of her status a rare space where they might escape, if only momentarily, the patriarchal gaze.

Except for slim details gleaned from the documentation of her sale to a new master in 1869, we know nothing of Henriqueta’s life. However, there were scores of similar transactions every month, and constant uprooting appears to have been a common part of slave reality, especially after the transatlantic trade ended in 1850. Henriqueta’s sale required her to relocate to the heart of the city, into a new parish only about a kilometer from her former residence, but in the small geographies that made up a person’s place and bounds in the nineteenth-century city, it was a move to a new, unfamiliar community. She certainly left behind neighbors and friends. And because her sale took place before the proclamation of the Slave Family Protection Decree later that year, which recognized for the first time a slave’s legal right to kin, she may have left behind children. She also moved from a part of the city where female slaves, serving as maids, cooks, and laundresses, made up a majority, to the rough and tumble downtown where male slaves outnumbered females two to one. Hence, a mere kilometer in Rio de Janeiro was a social and personal disruption, a sundering of acquaintance and kin.Footnote 4

Unshod her whole life, Henriqueta’s calloused feet were prepared for the sharp, irregular cobblestones that were common to the city center’s streets. Locals referred to the city’s crude paving as pé de moleque after a popular, lumpy candy much like peanut brittle, but that can be literally translated as “slave boy’s foot,” another association of slave soles with the early Rio street. We do not know Henriqueta’s particular assignments, and it is possible she spent much of the rest of her life cloistered in domestic duties, her contact with the street restricted to quick trips to Mass and views glimpsed out of the windows of her master’s home.Footnote 5 But for many of her status and gender, entering the street was a common, daily task, and female domestic slaves could spend much of their day running errands, laundering clothing in the local fountain, peddling goods, and engaging in other remunerative work, right on the streets. In a short period, Henriqueta’s feet would have acquired an almost prehensile sense of her new streets’ contours, the joints between the cobbles, the missing stones, the smooth flagstone pavers that fronted fancy shops, the compacted dirt and sand of unpaved lanes, the puddles, the mud, the prickly vegetation, and the dried blood and fish scales from yesterday’s market that clung to the soles. That a slave’s head and neck were often burdened with water, groceries, laundry, or saleable wares, pressing the feet all the more firmly onto the street’s irregular surfaces and declivities, accelerated the tactile education.

Henriqueta’s new neighborhood included two of Rio’s most frequented public spaces: Rua do Ouvidor, the city’s main street of high fashion and, in season, carnival dancing, and Rua Direita, the city’s chief commercial space that fronted the port and main square. The two streets intersected. Machado de Assis, Rio’s most perceptive narrator, described the notoriously narrow Rua do Ouvidor, despite its reputation as an “interminable alley excessively lit,” as the generative heart of the city. If the entire city were destroyed, but Ouvidor preserved, he wrote, it would, like Noah’s entourage saved from the flood, be the seed from which the city could fully regenerate itself. He gloried in its characterization as a place for loafers and loiterers, its slender confines forcing a familiar intimacy on all who went there. He accused those who wanted it widened of ignorance of confinement’s social beauties, a place where a man in one shop could shake the hand of a friend in a café across the street without losing his balance. “Streets that offer us easy passage,” he asserted, “hold little charm, neither do they inspire in us the desire to stop and see what there is to experience.” He observed that with a will, one could walk Ouvidor’s entire length in three minutes, but the trip, he asserted, generally took three hours; and one could gain more in interest and information by idling at the corners than by moving through with purpose. Brazilians were considered lazy by outsiders, but foreigners, he suggested, failed to understand that a deliberate sluggishness produced the street goods most prized by locals: interaction, news, entertainment, and community. It was also the place in which to mingle with and appreciate the opposite sex: Ouvidor was heavily frequented by women, at least by the second half of the century. To transit a street like Ouvidor expeditiously was to fail to understand what the street was for and why you came there in the first place.Footnote 6 Ouvidor represented community in its broadest, civic sense, a place to share with all those – many of them strangers – who made claim on the city as home, from the emperor to the slave. All belonged, even if not all were offered the same kind of welcome.

In 1850, Ouvidor was lined with jewelers, shoemakers, various workshops, and twenty-five newspaper and magazine presses.Footnote 7 By the later part of the century, the number of presses increased, and many shops were occupied by foreign keepers and French fashions. Beginning at the street’s western extremity on São Francisco de Paula Square, residents made slow progress indeed in the busy late afternoon, a haptic encounter, literally rubbing shoulders with other women and men – rich and poor, black and white, slave and free, sellers and buyers, deliverers and receivers. There were indeed many loafers, but for those who moved, movement was haphazard, “all crossing each other’s paths in every direction.”Footnote 8 As narrow as it was, Ouvidor was not viewed as having merely a linear function. It was space experienced as volume, meters cubed, rather than a line. People made all sorts of connections: intimate chatter was incessant, and in walking, eyes met eyes, fastening and releasing on a succession of faces strange and familiar. On Ouvidor, you could buy one of many newspapers, but if you wanted the latest news, you listened to the enveloping conversations, those spreading pure gossip, matchmakers announcing prominent weddings, and ship captains sharing news from Europe and prices in Africa. The smells of natural bodies and manmade perfumes mingled with the scents of restaurant kitchens, roasting nuts, leaking gaslights, toasting coffee beans, smoldering tobacco, and the soil of potted flowers. As you progressed toward the port, there were fewer suits, cigarettes, and polished boots, each progressively supplanted by baggy pants, cheap pipes, and unshod feet. The fragrances became increasingly organic: salted cod and fresh beef attracting flies; popping corn and nutty candies drawing children; kerosene, hay, the manure of mules, pigs, and dogs; and the bouquet of caustic soap emanating from the public fountain.Footnote 9 This was not a corridor. It was a living entity, a space in which the life of the city happened. João Pinheiro Chagas, a political exile who later became Portugal’s first prime minister, found Rio’s downtown streets in the late 1890s narrow, dirty, stifling, and poorly paved, offering the most uncomfortable transit. However, the street’s failure as an efficient passage failed to bother him much “because the life of the streets makes me forget the street.”Footnote 10

Much of Ouvidor’s diversity and focused life derived from the sheer number of its users. There was also safety in the absence of wheeled vehicles. For some time, Ouvidor, due to its narrow confines and burgeoning crowds, had been declared vehicle-free, at least from 9 am to 10 pm.Footnote 11 On Ouvidor, “nada de rodas,” nothing to do with wheels: no carriages, no horse carts, and no streetcars. In one popular anecdote, a man “very well gloved” in a smart carriage, smiling with confident authority, turned his driver up Ouvidor only to be abruptly ordered back by a low-ranking policeman. The notable insisted, stating, “[T]his carriage will pass because it belongs to the palace,” to which the policeman responded, “[E]ven if it belongs to Susana de Castro,” the city’s most famous consort and a favorite of men of the royal family, “it shall not pass. No wheels on Ouvidor. I keep my orders.”Footnote 12

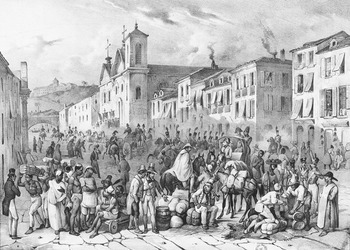

As Ouvidor opened onto the relatively broad Rua Direita, users did compete for space with the occasional wheeled vehicle, including mule-drawn streetcars running on narrow rails, a new addition to the streets from the late 1860s. But even these modern conveyances were notoriously slow, moving no faster than a brisk walker. The scene might still have been similar to that painted by Johan Moritz Rugendas, who depicted the street on a busy day, a bustling gathering spot of hundreds of individuals. He placed the spectacle of transpositional movement in the background, where it appears that a royal figure in a carriage arrives at the Nossa Senhora do Carmo church. But in the foreground resides the mundane, characterized not by movement but by stasis, scores of slave carters, female vendors, merchants, priests, gentlemen, ladies, muleteers, cabbies, and policeman, barely any of whom are engaged in transpositional movement. They take their places on the commons, where they belong and where they have as much right to stand, sit, chat, negotiate, observe, and argue as they do to move. They stand together in small groups interacting, or alone observing others. They sit on empty carts, on their bundled wares, or, often, directly on the pavement. And they look relaxed, as if they have been there for some time and have no plans to move on. A two-wheeled tilbury, with passengers, presses against their collective body, but it too seems to be seeking interaction rather than transposition. The street folk do not move for oncoming traffic; the traffic will find its way around them. From above, local residents, also unmoving, engage the street from their windows.Footnote 13

Figure 1.1 Rua Direita and the nature of the logradouro, c. 1825. The street as commons permitted, even invited, a multitude of activities. Residents understood the street as an outdoor room, a negative form of architecture that belonged to everyone and that was open to varied, creative uses. Busy streets like Rua Direita, the city’s main commercial space, offered an ever-changing spectacle of sanctioned and unsanctioned utilities.

This is the street of interest in this chapter: the mundane, the common, the everyday. I resist (not always successfully) the temptation to assume the role of the flaneur, the elite rambler popularized by Baudelaire and Dickens and practiced in Brazil by João do Rio and Aluísio Azevedo, who take to the streets in search of the exotic, the serendipitous, and the lurid. Still, the street of a century ago can be exotic to modern eyes. Modernity simplifies street life, tells us all where it is we should look, subsuming all of our senses to the dominance of our eyes. On the street today, it’s “eyes forward, both hands on the wheel.” The circus has only three rings; the traditional street, on the other hand, was a stage with too many human dramas to comprehend all at once, all of which overwhelms the modern gaze. It was complex, and it was open to rapid changes – additions and subtractions – in use and meaning. The unsettled and shifting nature of the street’s spatial practices impresses, and this chapter’s objective is not an exact chronology of evolving street practices but rather a demonstration of its spatial possibilities. When the street was an open commons and not yet dominated by transpositional movement, citizens devised and reinvented hundreds of creative ways to use the street to meet their social, economic, cultural, religious, and other needs, which altogether expressed the street’s multifaceted meanings. More to the point, with space, an open urban habitat, residents found a place in which to act out their most basic behaviors: to talk, to buy, to sell, to celebrate, to play, and to simply be with others of their own species.

Systems and Perceptions of Nature

The automotive street’s dominant flows have been habitually compared to the human circulatory system, which, despite certain limitations, is apt. As with the human bloodstream, where corpuscles flow through a complex system of arteries and capillaries, the streets, avenues, and highways of the city’s network serve as the conduits on which bodies and commodities stream from one place to another. As such, these systems are described as serving one function, movement, and when they perform below expectations, or fail, we call them congested or sclerotic. In prioritizing flow, we tend to disregard the street’s other functions, many of which still hold, if now attenuated and less visible.

The traditional street, with its multiple utilities, is too complex a reality for this simple analogy. However, if one delves into the bloodstream’s more complex functions, the metaphor can again be elucidating. Blood circulates, but it does so in support of the bloodstream’s most critical functions, which are access and exchange. First, and quite remarkably, the body’s network of arteries and capillaries access essentially every tissue and cell in the body: the bone’s marrow, the tooth’s pulp, and the hair’s follicle. The bloodstream effectively connects every space within the body with every other space, putting all elements in communication. Second, blood, once it has accessed a location, engages its most elegant machinery in the exchange of commodities and information. Blood consists of as many as 4,000 different ingredients that offer energy, nutrition, waste disposal, and antiviral and bacterial security. To the door of every cell, blood delivers glucose fuel, oxygen, both coolant and heat to regulate temperature, minerals and nutrients, protein-building blocks, clotting and healing agents, antibodies, hormones, enzymes, and a host of other elements, many containing vital information. Maybe most impressive is the bloodstream’s ability to accomplish all of this within a single conduit. In the same stream that blood carries beneficial sugar, oxygen, and antibodies, it also carries wastes, such as carbon dioxide, toxins, dead tissue, excess water, and salts, all of which it safely exchanges to organs of excretion.

In a sense, the traditional street, although on a large and crude scale, mimicked the bloodstream’s access and exchange functions. In a single conduit, a host of activities, utilities, and exchanges took place altogether and simultaneously. It was on the street that the city was provisioned with energy: food, firewood, and lamp oil, many of these peddled door to door, as were hundreds of other necessary items. The substantial peddling classes, referred to as the ambulantes, represented a mixed commodity stream in flow seeking exchange. Although there were formal and informal markets also located in the streets, householders did not need to daily enter the street to shop but simply waited for the baker, bookseller, florist, or the milkman, the last with milk cow in tow, to flow past their doors, each peddler sounding his or her characteristic call – a jingle, horn, rattle, bell, or whistle – to signal the potential for a specific exchange. Water was collected at local public fountains, many of them located in the squares and largos, and then carried through the streets, mostly on slaves’ heads, to households and businesses. Rather than relying on machines, even one as simple as the wheel, movement was effected largely on foot and on hoof: slaves carried their masters slung in hammocks, transported goods upon their heads and shoulders, and engaged pack animals for heavier items. The street was an organic machine without machines. Information flowed in the street in vocalized news and gossip, or it was sold in print form on the street corners by newspaper boys who sang out the headlines. Likewise, the city’s waste found its way to the streets to be excreted beyond the immediate urban bounds. Waste water and human excrement were also dumped onto the streets’ surface so that the rain might wash it away, or they were also commonly placed in large barrels such that slaves could carry them away to dump in the bay or a local stream. As in the bloodstream, in the city nearly all things flowed, intermingled, and exchanged in the single conduit of the street. And in some ways the street exceeded the bloodstream: it provided the city’s cells with essential light and air, and people, commodities, and wastes flowed not just in a single unidirectional stream but moved in all directions at once. The street formed an exceptional example of a hybrid in which nature’s space and culture’s activities entangled in ways that blurred the lines we tend to draw between them. The streets also, of course, played a critical social and cultural role that went beyond the ecological and commercial. The street accomplished both its ecological and cultural functions all in the same space, all at the same time.

By contrast, the modern street, while still a hybrid space, is a simplified one where lines are more easily drawn. The modern street zones activities and canalizes functions, simplifying the traditional street’s complexity. This began some decades before the car arrived, but the car accelerated the process and, in fact, demanded it. Flow took precedence, which required that many other functions be removed or rechanneled. The bed of the street, typically making up its majority, was progressively converted into an almost exclusive corridor for large, fast moving machines. Curbs separated the street bed from the sidewalks, channeling foot traffic to its own particular corridor. Water, now, rather than originating in fountains and moving in hands, or on heads and backs, was channelized into pipes running beneath the streets and directly into homes. Likewise, sewers and later storm drains were installed to carry away wastes that used to move on the surface. Energy, rather than arriving laden on the backs of slaves as firewood or even in the beds of trucks, increasingly arrived in gas lines that ran beneath, or electrical lines that were suspended over, the street. The power of muscles – thighs, shoulders, lungs, and tongues – was being replaced by actual machines – generators, pumps, motors, and horns and loudspeakers. The automobile did not drive all this change, and there were important benefits to channelizing some of the street’s utilities, but by dedicating the street’s surface to largely host movement, other utilities suffered in the transformation. In particular, those cultural and social functions provided by the street, that could not be easily and mechanically channelized, were diminished and often displaced.

Rio’s pre-automotive residents did not, of course, understand their streets as part of an organic machine. But they also did not see streets as cultural products or monuments. Strikingly, they perceived the street, a space that was unbuilt, unimproved, and held in common, as a remnant of nature itself. The space remained unproduced. In Eduard Hildebrandt’s 1844 painting of the space we last described, Rua Direita, the city’s busiest commercial street, the street’s inhabitants are made up largely of African women like Henriqueta, some walking, some congregating about the doors of the Carmelite church, but the majority are seated right on the street in conversation. Two dogs chase each other about in the foreground, amidst the ruts of cart tracks, but there is not a vehicle to be seen along the street’s entire length. If one were to just focus on the ground, the street itself, ignoring the shops, the facing Hotel de l’Empire, and the façades and towers of five baroque churches, one might guess that this, the city’s main street, was an unkempt farmyard or country lane. The street, which by 1844 is paved, is still entirely overlain with dirt, has irregular dimensions, and displays no apparent improvements – no curbs, no sidewalks, no planted trees, and no gutters.Footnote 14 We notice a striking distinction between the tall, substantial artifices of civilization and the low, rather raw reality of the dirt-covered street from which they emerge.

The traditional street, despite its place at the center of civilization and its intense use by humans, fell fairly firmly into the category of nature in the minds of those who used it. The city’s founders built homes, churches, palaces, and offices, but between the walls of their constructions they left strips and chunks of nature, whose main function was not travel or commerce but simple access. Early city builders, including those in Rio, thought of the street’s function as primarily a space left as they found it so citizens could maintain direct admission to their homes and monuments. The raw, unimproved, unmarked, and officially unnamed street was a cultural space, but in the minds of its users, it was also a natural resource, not unlike forests or fisheries. This sets the Brazilian street apart from a common perception shared by Lewis Mumford who wrote that “nature, except in a surviving landscape park, is scarcely to be found near the metropolis.”Footnote 15 In Rio, quite the contrary, the street was nature’s residue.

Roberto DaMatta has argued for a pervasive, cosmological dualism that divided the Brazilian’s mental universe into the two stark categories of house and street. The house represented honor, fidelity, authority, order, safety, and cleanliness; the street evoked the opposites: dishonor, infidelity, insubordination, danger, and filth. The concepts of house and street pervasively ordered the Brazilian mind.Footnote 16 Portuguese expressions further illustrate DaMatta’s point: to shout the word “street” at someone was the equivalent of telling them to go to hell; a “thing of the street” (coisa de rua) was something dirty, low, and vulgar; and to further contrast the licentiousness of the street with the fidelity of the house, when a couple legitimately married, their civic respectability rose to a new level, for they had become “casados,” the Portuguese term for “married” which literally means “housed.” The house represented civil culture; the street was raw nature, which encapsulated many of its undesirable associations. William Cronon has challenged the common mental separation of nature and culture, of city and countryside, arguing that we can no longer presuppose that “nature is the place that we are not.” Nature and culture, if such categories are useful, intermingle in nearly all places, even in large cities.Footnote 17 Still, we tend to want to separate them. The Brazilian view, while it saw nature in the city’s raw streets, maintained the same false dichotomy. It was just that the lines were drawn at the house’s front door rather than along some more distant boundary coterminous with the ancient city wall. Nature was distinctly separate, but it was close at hand, occupied, and used. The traditional street, despite its heavy use, was more “natural” than a carefully plowed field or an orderly planted orchard; it was less manipulated to serve human ends than many farms, forests, rivers, and parks, most of which, despite their obvious, intentional shaping by humans, still largely remain in the category “nature.” Street naming practices demonstrate that street spaces were significant parts of the city’s symbolic world, but giving names to streets, like giving names to other natural objects, such as lakes and hills, again made them no less natural in the minds of their namers.

The street’s perceived “natural” state can in part be understood by examining its origin in early urban planning. In laying out Rio, the founders had a variety of potential influences: Greek, Roman, medieval, and possibly even indigenous, the last by way of cities discovered elsewhere in the Americas that were often characterized by rectilinear streets and large public squares. In fact, the Tupi’s indigenous villages were themselves built around a central public space that they referred to as an ocara (ocaraçu if it were large). Some have argued that Rio’s urban plan was capricious, had no forethought, or was meant to imitate Portugal’s medieval cities with contorted narrow streets.Footnote 18 Close examination suggests otherwise, and part of this error in observation comes from looking only to the streets for an answer. Significantly, here as in Spanish American and European cities, the streets were not the ordering element. Surveyors did not plot the city by laying out the lines of the streets as is done today, but by laying out the blocks, or, more specifically, the lots and their frontages that would form the blocks. We have no founding documents for Rio’s plan, but that of Panama City from 1519 expresses well the approach:

In view of these things necessary for settlements … divide the plots for the houses, these to be according to the status of the persons, and from the beginning it should be according to a definite arrangement, for the manner of setting up the houses will determine the pattern of the town, both in the position of the plaza and the church and in the pattern of the streets.Footnote 19

What gave the city shape was not its complement of streets but the arrangement of its blocks. The architect Paul Spreiregen points out that before the modern era, the street was not “treated as a principal design element but as the minimal leftover space for circulation.”Footnote 20 Rio was a structured mass of irregular cells. The streets were not created. Humans built buildings on demarcated blocks, and the streets simply emerged. To this extent, streets, while not accidental, were not quite yet produced. Streets expressed irregularity and messiness in their composition because they were not composed.Footnote 21 João do Rio felt that streets were among the most human of spaces, bodies with souls, and suggested that in much the same way that we create new human beings, in “expectant sighs and fruitful spasms,” our streets birthed inadvertently in the human quest for more immediately tangible desires.Footnote 22 In Rio, as in New York, Boston, Lima, and Havana, officials did not give streets official names at their emergence between the blocks.Footnote 23 Like children, they were nameless when conceived.

In many cases there was almost no plan in the beginning; settlers simply plopped down buildings randomly on open ground. But soon method was imposed. In Rio, the blocks were produced irregularly – in shape and in size – which was reflected in the varied character of the streets. The blocks’ only regularity was that each aligned itself pretty well with its neighbors. But one would be hard pressed to find a perfectly square block in colonial Rio, and it would be almost as hard to find one that was a perfect rectangle. In shape, we can characterize the city block only as a four-sided object whose sides were usually straight but often not parallel. Since each block’s corners generally aligned themselves with the corners of three other blocks, Rio’s streets had continuity and intersections, but they did not have regularity, nor were they rectilinear. Streets broadened, narrowed, and changed direction, all depending on the shape and alignment of the neighboring blocks.Footnote 24 What was true of the streets was also true of the squares. Lilian Fessler Vaz’s study of Rio’s squares notes that not a single one before the nineteenth century was “regular” – that is, had the shape of a square or rectangle. Of the eighteen she examines from the eighteenth century, only three approximated regular geometric shapes. Rio’s squares, like her streets, were an odd collection of poorly defined spaces shaped by the blocks and buildings that irregularly surrounded them.Footnote 25

In size, city blocks could range from as many 45,000 square meters with 150 building lots down to a mere 1,200 square meters with as few as three. Yet blocks in Rio substantially dominated the urban landscape. The space dedicated to, or better, left over for, streets was minimal. On average, Rio’s central streets were no wider than 5.5 meters, and frequently narrower. Many downtown streets were insufficient for two carts to pass one another without grinding their axle hubs against the sides of the houses. With its narrow streets and busy traffic out of the port, Rio appears to be among the first cities to establish one-way streets, an innovative spatial practice that astonished European visitors. The direction of travel was (and still is) called “the hand” as signs mounted on walls pictured a hand with index finger extended in the direction of travel. The width of the streets was determined, of course, by how far apart blocks and their building alignments were platted, and in Rio we do not know if this was done by rule or custom, although the narrowness of the colonial streets suggests surveyors may have followed the pattern formalized by Spain’s Philip II: that in cold climates, streets should be wide to allow the sun to warm its inhabitants, and in hot climates narrow to provide shade. Across the region, colonial streets in tropical Havana, Mérida, and Rio are quite narrow from frontage to frontage, generally less than 6 meters, whereas in highland Mexico City, Quito, and Bogota, streets were 9–12 meters wide.

Blocks provided Rio with whatever order it had, and what determined the alignment of the first blocks was the orientation of the coast. The beach, not the compass, laid out Rio’s loose grid. Many of Rio’s first streets were technically boqueirões – that is, streets that opened onto the port. And as the early port was presumably a naturally curving waterline, Rio’s first blocks were built to face the water along a gentle crescent that became Rua Direita. Hence, each block faced the beach sitting at a slightly different angle from its neighbors. This made the transverse streets emerge from Rua Direita at right angles, and hence Rio’s east/west streets fan ever so slightly from the port and are not parallel. The same logic was used in laying out blocks in colonial Niteroi across the bay,Footnote 26 as well as more starkly centuries later when laying out the crescent beachfront suburbs of Copacabana. Compared to the city’s somewhat orderly blocks, streets were irregular by comparison, appearing as narrow spaces that come at odd intervals and unexpected angles. The sides of blocks are straight and true, but a facing block did not necessarily run parallel to its neighbor, so streets were not always uniform in width, which could vary over their length, sometimes becoming so broad as to form small squares or largos. And streets often changed direction slightly from one block to the next as the blocks themselves had slightly different orientations.

Urban maps until the second quarter of the twentieth century attest to this perception of the city as ordered urban blocks built on a raw landscape. Map makers represented the city by illustrating the city’s blocks, and sometimes individual buildings, as distinct objects – human constructions on a blank field. The built environment dominates, leaving the streets, squares, and beaches as interstitial remnants of nature’s original space. The blocks and buildings made the figures; the streets were artistically and literally the ground. Colonial maps and illustrations of Rio’s streets depict the ground, the unbuilt space, as all of one continuous piece, from street to square to beach, with no distinctions.Footnote 27 Maps also presented streets at their actual scale relative to the blocks, emphasizing the street’s relative spatial insignificance. Yet significantly, streets were always represented as actual spaces, not as abstracted lines representing space.Footnote 28 Once the automobile began to dominate streets, maps became complete inversions of their former selves. Now urban maps are called street maps because they represent the city as so many abstract lines, not spaces. The built environment is now the ground on which unscaled, colored lines are inscribed to represent the “figure” of the streets.Footnote 29

If manipulation is what begins to unmake nature, then the failure to modify and improve the traditional street extended its status as nature for centuries. Most of Rio’s streets persisted as raw, bare ground, unpaved and unimproved until the eighteenth century, and often for another century even downtown. The first improvement to the street was the paving of the testada, the street space immediately in front of the house. Sometimes mistaken as a sidewalk, and certainly used that way when the streets were muddy or trafficked by vehicles, the paved testada, which was completed at the owner’s expense, served more as a front porch and protection against water at the foundations than as a pedestrian corridor. Each testada might be paved in different materials, at different widths, and varying grades, but with no curbstones, lying at the level of the street itself. Likewise, as many houses had none, the testada was discontinuous.Footnote 30 On steep streets, the testadas gave the effect of a series of broad, irregular platforms. The rest of the street was generally unpaved and frequently ungraded, making the ground uneven, rough, and poorly drained. At best, a street might be periodically graded, with hand tools, so that water flowed to the center where a narrow ditch was provided. If a street was paved, abutters, those who lived on it (not the city) paid for it. Still, most streets into the early nineteenth century remained wall-to-wall dirt.Footnote 31 And while some prominent squares saw pavement in the eighteenth century, none were landscaped, curbed, or honored with statuary until late in the nineteenth century.Footnote 32 Even when paved, streets were often filled with dirt. When it rained, some streets became streams and rivers. Soil and water mixed to form deep, muddy thoroughfares that were impassable to all except shod hooves and unshod feet. And in Rio and other coastal cities, such as Paraty even today, the highest tides rose to cover the lowest portions of the public streets with some regularity. As in most commons, there were few incentives for individuals to make improvements to the street. In these circumstances, the urban commons were no more produced than were fish in the sea or timber in the forest.

One might suggest that streets were unnatural in having been significantly reshaped by their very trampling and by the additions of human trash and wastes. But by many reports, even the busiest streets were covered with grass, choked with weeds, and invaded by shrubs and trees. Locals used the term “mato,” usually translated as “jungle,” to describe vegetation in the streets, and in Rio’s first suburbs residents complained that it grew a meter high. In the seventeenth century, locals said streets had more vegetation than anything else. Rio’s citizens, even those living downtown, were making similar complaints into the early twentieth century.Footnote 33 Tiririca, a tall, invasive sedge from Africa, was among the most common street plants, well adapted to packed earth and resistant to trampling. In one of the earliest photos of the city, Revert Henrique Klumb framed Castelo Street in 1860 choked in places with an impassable scrub.Footnote 34 Pedestrians and drivers of vehicles used streets selectively, avoiding rank vegetation, ruts, high spots, and mud, following the most efficient trajectories available. This strategy resulted in desire lines, urban trails that give the impression that traditional streets were an organic collection of social trails, not single, coherent thoroughfares.Footnote 35 Occasionally before religious festivals, the city ordered a crew to uproot weeds, hoe grass, and fill in holes, creating an adequate space for the coming public event. Entrepreneurs pitched new herbicides, such as one branded “Soldier’s Water,” that they claimed would bring about the final extinction of plants on the public street.Footnote 36 However, some street users held the vegetation as beneficial: laundresses, who formed a major sector of the city’s employed, laid their expansive washings on the streets’ grass and scrubby vegetation to bleach and to dry.Footnote 37

“Filthy,” like “narrow,” was a relative term, but it is also one we misunderstand this side of modern hygiene. Foreigners found Rio’s streets narrow, but they commented little on their uncleanliness.Footnote 38 Locals, on the other hand, rarely mentioned a common street’s straitness, but described particular streets as suja (dirty) and imunda (filthy). However, sources before the turn of the twentieth century strongly counter such local accusations. It is rare to find the smallest evidence of trash, offal, or waste in street depictions, except in active street markets. Some artists might be accused of idealization or pure obfuscation, and of course notable streets got more attention from artists than back alleys, but the available visual record suggests that the traditional street in Rio was cleaner than many streets today. Most of the time, the street was depicted or photographed as nothing short of immaculate. Part of the explanation for the lack of trash and waste is that in pre-industrial societies nearly all materials had economic value. Bent nails, rags, chaffs of paper, even tobacco wrappers were harvested from the street to be recycled or repurposed. Scavengers, Do Rio wrote, “carved out a livelihood clocking hours cleaning the streets.”Footnote 39 Brazilians also have had a long tradition of street sweeping each morning to remove the previous day’s detritus, which was legally required in Rio from the 1820s and which is still common practice in provincial cities. In the 1840s, the city provided daily carters to take away the piles, and in the 1870s, private hauling contracts were established, most famously with a French immigrant Pedro Aleixo Gary; Rio’s ubiquitous street cleaner has been known as a gari ever since.Footnote 40

What locals and officials complained about was actual dirt and mud, and the other organics that intermixed with them, such as rotting leaves and pulverized manure. Unpaved streets were by definition “dirty,” and the main justification for paving was to overlay nature’s earthy foundations, to reduce dust and mud in the street. But even once paved, the streets quickly filled with organic and mineral soils: the city’s steep surrounding hills were in constant erosion, their components finding their way down to the streets, and the dust and mud from unpaved streets tracked onto the pavements. In fact, in São Paulo, where the soil was alluvial, residents, after a good rain, panned the contents of the gutters for particles of gold.Footnote 41 Elite complaints about dirt were direct attacks on the raw, untamed state of the streets, on their naturalness, not on human trash or garbage. The streets evinced nature because, paved or unpaved, they were ruled by soil.Footnote 42 The street’s condition as a raw and unimproved space served as an important marker and signal that the street was indeed a common space that belonged to nobody in particular.

There were, of course, rules for street users – humans, animals, and their associated vehicles – which included many prohibitions. The street was and remains the most regulated of human spaces, and one might argue again that a space so heavily imposed upon by official ordinances and informal rules could not have been understood as natural. But regulation is the norm on most commons, be they fisheries, forests, or grazing lands. Because they are common, they demand rules to ensure access to all legitimate parties and to decrease the probabilities of conflict over the resource. This too did not make the street any less natural in the eyes of those who used it, any more than forest regulations did for forests. However, what was being regulated on the street was behavior, not access. And many things were regulated, from legitimate fun to illegal crime. Cabbies and carters had to register their vehicles; streetcar companies and kiosk proprietors had formal concessions; and peddlers and beggars were supposed to be licensed. The street was not to be a free for all. In the months before street festivals and carnival celebrations, clubs, churches, and brotherhoods all petitioned the police chief for the license to parade and dance in the street, and they did so using established bureaucratic forms. In 1906, there were 175 such requests associated with carnival.Footnote 43 The chief, it appears, always granted them, but this was a means to give all access to the street while making it clear that the city regulated the space for the common benefit and that all activities fell under specific rules and expectations.

Despite police and the city’s best efforts, the streets were never orderly. There was too much space, there were too many people, and maybe above all, there were too many rules to make official regulation of the street anything but a vacuous claim. In fact, much of the activity on the street was in direct contradiction to the rules: slaves sang and danced together in the streets, including capoeira, a form of martial dance, despite rules against slaves forming groups; peddlers worked without license; drunks and non-drunks became disorderly and abusive toward their neighbors; prostitutes solicited openly; men rode their horses too fast; and wagons went the wrong way on one-way streets. The street also had a distinct reputation for violent personal crimes, including assault, robbery, rape, and murder. Still, the street remained an attractive place, amenable to human presence, and it was safer than the many criminal anecdotes would suggest. Most street crime was petty, and it was the large number of people in the downtown streets in particular that tended to keep it petty. Social policing worked to keep certain illegal activities in check, but the social will also offered collective support for certain, accepted infractions against the rules, even from the police, who worked on the streets, too. Despite its criminal associations, the street, at least by day, offered safeties and protections that the patriarchy of the home, which acted without public censure, would not offer. Most murders, rapes, and slave punishments took place indoors; hence, for many, especially among the servile classes, the street might have been considered safer than houses.

The most vital rule associated with the street was its protection as a common space, a statute so fundamental and recognized that it may never have been written down. Neighbors might complain about an individual’s behavior on the street, but they could not challenge their neighbor’s presence or right to occupy space there. Luiz Edmundo remembered various street characters from his youth – undesirable sorts who were broadly familiar and ever present in the street.Footnote 44 Many held their ground when their space was challenged and declared its common status openly. One Maria da Costa was angry at her friends for not including her in their evening plans. When she spotted them at an intersection, riding together in a coach, she hurled a few stinging invectives at them, and then, to spite their fun, turned up the narrow street ahead of them to walk at the slowest possible pace. The enraged driver shouted insults at Maria, demanding she make way. But Maria calmly turned to the man and asked, “[I]s not the street the king’s,” a shrewd legal observation to which the driver could only give quick assent. He and his passengers then held their peace until Maria turned triumphantly down a side street.Footnote 45 What Maria had really said, in a politically astute way, was that the street was common, and she had as much right to the space as anyone. The traditional street was contested, in part because it was common, but it was always shared, available to even those who were known to refuse to follow its stated rules. The streets were, hence, both mine and thine, and its perception as nature, raw, unimproved, and unproduced, was a primary indicator of its common status.

At the Boundary: Walls, Windows, and Doors

The built and un-built stood in opposition to each other, and since the days of Gilberto Freyre, who also held that house and street were enemies divided, historical work has tended to focus on the undesirable and violent exchanges between them: those who invaded the honorable home – burglars, rapists, army drafters, mosquito abaters, and medical vaccinators – challenging male power and property; and those who attempted to elude the house – domestic servants, and even daughters and wives – flirting through and slipping out of windows to expose themselves to the street’s moral and medical hazards. The house was supposed to speak order to the street’s chaos, hierarchy to its insubordination. Yet the dualism of the house and the street, although it had very real consequences, was largely a fiction championed by elite men to bolster their insecurities about the limits of their power over either house or street. Despite the cultural separation, physically and practically, the house and street were intimately and unavoidably coupled.Footnote 46 It was through the windows and the doors that many of the street’s bloodstream exchanges took place, and hence windows and doors figure prominently in the street’s function. What was a significant cultural barrier was at the same time a permeable social and ecological boundary.

Houses, shops, and even churches were built on grade, making it possible for bodies to cross the boundary between house and street without breaking stride or stepping up. Rio’s city edifices had neither stoops nor steps. The streets were too narrow to allow them.Footnote 47 This put the world of the house and street on the same level, at least on the first floor, and in 1808, of Rio’s total 7,500 commercial and residential buildings, 4,800 were single-story, which would remain the pattern for much of the century. An individual on the street stood at eye level with those in the house as they, through windows and doors, exchanged glances, gossip, or goods. The boundary was meaningful, and tenants could prevent much of the street’s flow into the house by shutting doors and shutters, making the façade an actual physical barrier. As João Pinheiro Chagas reported, homes and shops were always prepared to slam their doors and shutters tight at the cry of “Close it up!” due to some disorderly behavior: a fist fight, tumult, or an armed youth firing his pistol while denouncing the government.Footnote 48 But the reality was that many chose to permit the street to enter the house because such flows were considered positive. Common domestic architecture in colonial and early nineteenth-century Brazil seemed constructed intentionally to interface with the street. Street-facing façades were pierced with an almost overabundance of doors and windows. On many façades, there was as much fenestration as wall. Windows would remain largely unglazed for the entire nineteenth century; the first storefront panes installed on the fashionable shops on Rua do Ouvidor by 1850 were only for show, to be removed each evening for storage.Footnote 49 Unglazed windows were shuttered, but most shutters were thrown open during the heat of the day. John Luccock described a one-story apartment he rented, “equal to most in the place” whose sitting room was “enlightened by one window, without glass or lattice, and which, when the shutters were open, completely exposed the room and all that passed in it.”Footnote 50 Another pointed out how close the house was to the street, writing of a residential room whose “windows … opened directly upon the pavement, with never an inch of grass-plot or other border of mitigation to isolate the house from street.”Footnote 51 When shuttered with the typical louvered and pierced jalousies, residents still kept an eye and ear on the street, the source material for much of the neighborhood’s gossip. Doors and windows accessed the commons, and more access meant more of the common’s benefits: light, air, movement, commerce, and conversation.

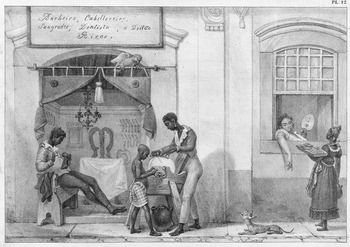

Figure 1.2 The Barber Surgeon and the interpenetration of the house and street, 1821. The street’s most important function was to provide access to the built environment, which included the exchange of goods, services, and information between the house and the street. Walls formed an important, recognized boundary between private and public realms, but an abundance of doors and windows made the boundary porous. Like an ecotone, this ecological transition attracted much of the street’s densest uses, and many lived and worked on that critical line. Note the barber’s bench, whose legs are specially built to span the gap between the two worlds.

Bodies occupied space in the street and in the home, but there was a strong predilection to inhabit the boundary between them. Thinking of it ecologically, the façade formed an ecotone, a uniquely rich habitat formed by the meeting of two others. The exuberance of windows and doors played a role in ventilation in a hot tropical city (an insufficient one in the eyes of hygienists), but it also encouraged interpenetration. For many elite women and girls in particular, but also commonly slaves, the favored spot was to sit in a window, shutters wide open, with elbows propped on the sills. Debret made multiple sketches in the 1820s of Rio’s women, free and slave, framed by their colonial windows, with arms or chins resting on the sill.Footnote 52 Special sill pillows were fitted for the purpose, and the sill itself was called the peitoril, the place for one’s chest. Young women who leaned into the street were referred to as moças janeleiras or window girls.Footnote 53 Today, some residents place at their windows namoradeiras, life-size mannequins who lean elbows on window sills, gazing at the street below, evoking a time when real bodies found the street a place worthy of spectating. The fact that cloistered women often participated in the street at a distance suggests some separation, but the house was still an outward looking institution and not a convent that focused on an interior courtyard. Despite the street façade’s porosity, which side of the line one was on mattered. Prostitutes, for example, who worked “at the window” (that is, soliciting customers from inside the house, even if they leaned out) were legally protected from arrest for vagrancy and were not bound by the rules of curfew. Prostitutes who worked the streets were vulnerable to harassment and arrest. The house lent a certain respectability and security to the most maligned of activities.Footnote 54

Even as suburban homes began to be set back from the street with intervening small gardens, many still clung to the old ways of staying connected to the street. The successful coffee planter and slave dealer Antônio Clemente Pinto, the Baron of Nova Friburgo, built a luxurious manor that would later become the presidential palace just south of downtown on a massive lot that extended from Catete Street all the way to Flamengo Beach. There was some dispute between the baron and the baroness over where to place the house on the lot, but in the end, rather than build in the central gardens or overlooking the bay, the baroness prevailed. The palace’s façade was built tight to the alignment of busy Catete Street, which carried traffic south to the new suburbs; the baroness, tired of plantation landscapes, insisted on the ability to enjoy the views and the movement of the street from the windows of her home. Even fifty years later, a writer complained that foreigners had scooped up all the loveliest home sites in the hills and on charming beaches, spaces abandoned by Brazilians because natives “prefer living in the city streets rather than among the natural, supernal splendors.”Footnote 55

Like windows, doorways themselves were favored space. While architects have suggested that the placement of a building’s main entrance is the “single most important” decision in a building plan,Footnote 56 the Portuguese evaded it by multiplying the entrances. Portuguese colonial architecture may have exhibited more doors per frontage than any other national style. It is a veritable architecture of doors. A typical building, just a few meters wide, might have four or more doors at ground level. On commercial streets as well as on the narrowest of alleys, such as Beco da Moura, frontages were essentially wall-to-wall doors, as if every room needed its own access to the street, or, as in many cases, each room needed multiple entrances. In 1820, one Miss Peppin sketched seven narrow buildings along Rua Direita with a total of nineteen doors on their frontages. In a short stroll, a pedestrian would pass hundreds of doors, many of them wide open in the daytime, as they are in Peppin’s depiction.Footnote 57 And, of course, many upper story colonial windows were in fact full-size doors, giving access to small, projecting balconies, of which there are thirty-three in Peppin’s illustration. The doorways’ thresholds were not just passed over but lived on. If women ensconced themselves in windows, men preferred to lean against door frames. Gathering at the doors appears common at night as well. Manuel Antônio de Almeida’s Memoirs of a Militia Sergeant intimates that on moonlit nights, few stayed inside in the early nineteenth century. Residents gathered family and friends at their thresholds on mats set on the street’s surface, in this instance on Rua da Vala (today, Uruguaiana), to while away the evening hours with food, drink, conversation, and song. Some, he claimed, slept the night on the street right around their doorways as the coolest option on hot summer nights.Footnote 58 In an early nineteenth-century depiction of carnival, the usual water fight does not take place in the street, as one typically assumes, but between the houses. Revelers throw wax balls full of water from inside one house, across the narrow street, and into the neighbor’s windows and doors, an excellent example of interpenetration permitted by multiple orifices facing across narrow public spaces.Footnote 59

Façades, windows, and doors formed the walls that enclosed the street’s room, and their décor adorned and graced the street as much as they did the house. If walls were built to enclose interior rooms, they were decorated for the benefit of those in the street. Significantly, walls enfolded Rio’s old streets at a scale that humans found congenial. Architects who criticize the broadness of modern streets have argued that to create street spaces amenable to human experience, the proportion of street width to building height should not exceed six to one, and some hold that the ideal is closer to one to one.Footnote 60 On a typical Rio street, 5.5 meters wide, with a mix of buildings of one to three stories, the average ratio was very close to that ideal. At that scale, walls gave the street a sense of airy enclosure without being stifling. In the early twentieth century, incipient skyscrapers, which were much maligned by some local commentators, blew colonial proportions out of scale. Even in cases where streets were widened, the ever-greater heights of new buildings made street spaces feel oppressive and dark.

Possibly more important than the street’s shape was the built environment’s physical and social arrangement around it, which impacted the street’s place in the construction of community. The frontage of a typical building, regardless of height or purpose, was narrow, less than 5 meters except in the homes of the wealthiest.Footnote 61 This meant that in a short length of street, one would find numerous households. Narrow façades created a density of settlement that contributed to the street’s liveliness, to the large number of bodies on the streets, at the doors, and in the windows. They also contributed to a diversity of activity and class. Early cities were not economically zoned; along any typical street one would find residential housing, retail shops, workshops, churches, convents, government edifices, bars, and, later, cafés and restaurants. Even the royal palace, which was the residence of his imperial majesty after 1808, Marco Morel points out, was nothing like Beijing’s insulated Forbidden City but surrounded on all sides by shops, fish and vegetable markets, a slave cemetery, warehouses, and barracks.Footnote 62

Likewise, the house/street arrangements did not express class segregation. The rich and the poor lived intimately side by side and on top of each other, in the city and also in the early suburbs.Footnote 63 Aluísio Azevedo set his late-century novel, The Slum, in the suburb of Botafogo on a street that contained a restaurant, a bar, a tenement, a working quarry, and a rich merchant’s house, all within the space of three façades. That small space contained residents who were slaves, former slaves, immigrants of diverse origins, thriving merchants, student boarders, laundresses, titled nobility, police sergeants, debutantes, prostitutes, and tradespeople. The walls of edifices and tenements might segregate by color and class, but once bodies passed out their doors, they came into immediate contact with next-door neighbors who were different in color, age, wealth, origins, and gender. The street’s extreme density and diversity – of both users and utilities – contributed to the production of a lively community, one in which instances of connection, interaction, and exchange were sustained at a fever pitch. Historians tend to focus on the street’s contests, divisions, and conflicts, which were no doubt real, but significantly, despite many ongoing tensions, people in the street mostly tolerated each other, accustomed to mingling with individuals and crowds of disparate means, origins, and aims.

Community as Street Utility

If streets remained physically unproduced and largely unimproved to this point, they still served as an important resource – a place, for the production of the city’s commerce, sociality, and play. Among their most important products was community, a concept that is a central feature of human settlements, but unlike commerce, transit, or even kinship, is rather difficult to measure and document. Streets also produce communities that are difficult to define and bound. They did not produce communities of interest – that is, Rio’s diverse neighborhoods did not form groups who shared an occupation, a political view, a class, race, or hobby. The interests of the street were often contradictory, divided, and factional, containing individuals of diverse concerns, origins, statuses, and languages. Nor did the traditional street necessarily produce much in the way of social capital. As with the members of any ecological community, street users exhibited mutualism, but also competition and predation. Although mutual assistance was not uncommon, residents did not expect members of their street community to collectively stand ready to aid them in their hardships. Hence, the street did not aspire to the production of a utopian community. Streets were merely communities of place, where membership was determined organically by simple geography. Yet the space provided by the street offered residents free membership with community privileges and essential human amenities: a sense of belonging that, however hard to measure, was part of what it meant to live in a city and neighborhood. Today we think of the city as a place of anonymity, but Rio’s neighborhoods were places where people were known.Footnote 64

Today, streets make convenient and effective boundaries between individuals and all kinds of administrative units. In the past, streets, because they linked people together, were neither seen nor used as boundaries. For example, the limits between parishes, which later became the bounds for the city’s secular, administrative districts, were not marked along streets, which would have placed people living on the same street in different ecclesiastical and civic entities. Rather, such boundaries were drawn down the backs of blocks. The Sacramento Parish, for example, included residents on both sides of Marechal Floriano Peixoto and both sides of Ourives but excluded their immediately rear neighbors who were parts of other parishes. The street was the space of community, and hence it did not make sense to divide residents and parishioners with the same streets that made their community.Footnote 65

Available space alone, of course, is insufficient to produce even communities of place. People living, working, and moving together, sharing urban space, as in a modern apartment building or a bedroom suburb, can fail to create anything but the thinnest sense of community, and many of our modern living arrangements produce little as well because in part they provide insufficient and ineffective public spaces on which to build it. A community of place requires the sharing of information, largely personal information; to be part of a community, one must know one’s neighbors and be known by them. And this was an essential function of the street – a space on which to meet one’s neighbors and share information about each other, directly or indirectly. The difference between a stranger and a neighbor is an introduction, or often little more than second-hand gossip. When one learns that an oft-seen face on the street goes by the name Pedro and lives in the tenement behind the bakery, Pedro ceases being a stranger and becomes a small part of one’s community, even if you have not physically met or been formally introduced. On the traditional street, one’s knowledge of Pedro increases over time: he is married to Maria, who is from Minas and sells homemade sweets; he has three young children, one of whom is sick; he works as a mason; he is honest, neat in appearance, and enjoys a well-pressed suit on weekends; he is introverted but not unfriendly, except if drunk, when he becomes combative toward even his friends. Soon, Pedro knows as much about you as you do about him, and thus includes you in his community. The street was a space where such information about one’s neighbors was trafficked and observed, and that information formed the community’s essential links. The histories and characters of hundreds of individuals were spoken, recorded, and retransmitted on the street, often over multiple generations, and it was this information that gave the community its foundation and identity. Community was written on the street where character and plot were under constant development and revision. And although neighbors might share a few local events in their memories, they often did not share a common history in the way a nation or an ethnic group might. The community’s identity consisted mostly of personal information, hundreds of individuals’ narratives, rather than a single cohesive story.

The communication of personal and other information took place in myriad ways, and it was interaction itself that gave the street much of its meaning. The streets, which were relatively quiet and slow-paced, offered a space amenable to talking, and the talk was reportedly incessant. Thomas Ewbank portrayed Rio’s mid-century streets as quietly communicative relative to his experience during long residences in London and New York. He described the common mechanism to initiate conversations: a restrained “pshiu” or shooshing with the lips accompanied by a hand signal, palm down, the fingers repeatedly closing, drawing the targeted conversant to the signaler, a practice not entirely dead today. He noted that there was no loud bawling after each other in the street. “In this quiet and ingenious way all classes communicate with passing friends with whom they wish to speak.”Footnote 66 If the streets were quieter than in other major cities of the time, which is doubtful, they were quiet enough for easy conversation. However, residents did not reportedly speak quietly, did not seem to cherish privacy, nor did they have to be interrogated to extract personal and confidential information. Olavo Bilac argued that Brazilians could not live without the noise of human voices and could not keep their mouths shut, which explained why throughout their history they could not launch a political conspiracy before news of it reached the ears of authorities.Footnote 67 Living in close proximity with so many others, observing and sharing the comings, goings, and doings of one’s neighbors, formed the core of much of the street’s exchange. Gossip, which carries a negative connotation in both English and Portuguese (fofoca), served a positive, community-building function. It was of little use or meaning to those outside the community, which in part explains the growing opposition to it in an increasingly anonymous city, but it was essential information for insiders. One needed to know one’s neighbors with some intimacy to be able to spark a conversation with ease, to interact with them judiciously, to avoid unnecessary offense, or to keep information from those, such as the jealous husband of an unfaithful wife, who all agreed ought to be the last to know.

The community’s social life and social health depended on chatting. Biological life depended on economic exchange that also took place largely on the street, person to person, which intensified the street’s role and its opportunities for building community. Street peddlers, as a chief form of commercial exchange, were among the most commonly treated subjects of city life – exotically by foreigners in the nineteenth century, who found them a colorful and lively topic, particularly slave peddlers, and then nostalgically by Brazilian writers in the early twentieth century, by which time peddling had begun to sharply diminish in the central city.Footnote 68 The practice extended back into the colonial period and seems to have peaked at the end of the nineteenth century due to emancipation in 1888 and rising foreign immigration.

Residents depended on street peddlers, the ambulantes, for their daily needs, and peddlers contributed substantially to the diverse forms of movement and activity of the street. They called out to potential customers and approached residents intimately, at the windows and doors. The traditional street was a sort of reverse shopping mall, one in which the shoppers stayed at home and the “shopkeepers” came to them in a steady stream with their wares on their heads, in trays, or pushcarts. Some peddlers, consisting of men, women, and even children, came every day at anticipated hours offering bread, milk, newspapers, water, lemonade, juiced sugar cane, dried beans, fresh fruit, ice cream, poultry, rice, cigarettes, pastries, eggs, cigars, matches, candy, and ice. Many clients had subscriptions for the regular scheduled delivery of fresh roasted coffee or firewood. Jorge Americano could remember from his childhood the very hours in which specific commodities arrived at his door each morning, and in the afternoons, his street was full of candies, ice cream, and cool drinks.Footnote 69 Other peddlers came intermittently: those who sold pots and pans, brooms, baskets, houseplants, fabric, popular novels and devotional books, flowers, horses, edible roots, goats, hay, furniture, and pets; those who offered such services as knife sharpening, letter writing for the illiterate, chair caning, message delivery, or family portraits; or those who purchased old rags, metal, shoes, or bottles. While some of these offerings could be found in weekly markets and shops, residents liked the low prices and, significantly, that the price included delivery. To carry goods in the street, even your own shopping, was an indicator of low status, so acquiring goods at your door evaded the need to carry your own purchases or to engage a slave or carter to convey them for you. By the early twentieth century, some local merchants with rents to pay complained about the peddler’s unfair competition, but housewives often came to the ambulantes’ defense due to their competitive prices and convenient service. In other cases peddlers served as salespeople for the local merchants.Footnote 70

For foreigners who reported on these activities, the peddlers were strangers and strange, outsiders who roamed local streets in search of reluctant customers. But locals recognized the peddlers as neighbors or, at the very least, as familiars, many of whom had worked their daily routes for years. The peddlers reciprocated these sentiments. In Portuguese, the term freguês today generally refers to any customer, but in the past it referred to one’s habitual clientele, those repeat customers a peddler relied on for daily commerce. The term derived from freguesia, which was the smallest administrative unit in Portugal, smaller than a parish, and hence is the equivalent of neighborhood. Customers were neighbors in the literal sense, and many peddlers did not work an anonymous street but their own communities. Some, like the breadman or the milkman, might have come to one’s door for years, building bonds and familiarity. Sales took place through windows and doors, but some salespeople, such as those who sold fashions, fabric, and furniture, demonstrated their wares inside the home. Peddlers sold merchandise on credit, which required a certain degree of trust as well as repeated, regular visits to collect payments. In the earliest years of photography in the city, peddlers were a popular subject. Most such photographs seen from our distant present appear to be of types – broom vendors, candy peddlers, and knife sharpeners – but to residents, these were recognized people. One such portrait was of Castro Urso in a ragged collar and pristine boater, a widely recognized seller of lottery tickets.Footnote 71 In 1933, the artist and cartoonist Anísio Oscar Mota, better known as Fritz, produced a sculpture of a newsboy which was placed on Ouvidor Street. The boy, in ragged clothing and floppy hat, did not represent all news peddlers but specifically José Bento de Carvalho, a notoriously loud and single-minded purveyor of the news, at the age of ten.

One resident’s interaction with his bread boy suggests that community building was based on frequent, intimate contact. The narrator wrote of his association with an industrious padeirinho, a young boy who delivered bread on the street at 6 am sharp, regardless of the weather. He was not much for gossip, but his maturity and businesslike responses made him a popular figure as he literally ran with baskets of hot bread produced by his father. The boy, who wore long pants like a man, got upset with customers who did not come to the door promptly as it made him late to his next customer, and to those who complained of high prices, he diplomatically noted the rising cost of flour. The narrator reported that daily interaction created in him a deep bond of affection for the boy. Then, suddenly, the boy stopped coming, and the whole neighborhood asked after him. His father, who now took over the duties of delivery, explained in tears how his boy was down with the recent epidemic, and his daily reports noted his son’s decline into fever and deliriousness such that he no longer recognized his parents. Evidence of the plague’s virulence was in the street as doctors themselves made house calls, peddling medicine and hope. The plague became so severe that the delivery of bread ceased for a time. Then, one morning, the narrator responded to the boy’s familiar call once again, to find him hale and hearty. The boy was greeted, to his embarrassment, by hugs from his customers, by which he felt detained in his duties. By the simple process of daily exchange, intimate information was shared, and it was in these kinds of mundane interactions, not exceptional events like carnival or religious processions, that meaningful communities were built on the streets.Footnote 72

Not all the interactivity of commerce took place door to door; it also took place on the streets proper. Customers went to known street corners where barber/surgeons, almost always of African descent, offered services as varied as haircutting, the removal of parasites, bleeding, and tooth pulling, right on the street where all your neighbors observed what ailed you. Many vendors of drinks and treats targeted customers gathering in or passing through crowded squares. Debret noted that it was typical for men of the more leisurely classes to assemble in the palace square every day at 4 pm to enjoy the breeze, watch the shipping, and converse. Female vendors charmed and flattered regular customers, offering drinks of cool water from the fountain with the purchase of a sweet or pastry. And the men, he described, were generous in the exchange because of their long acquaintances with particular women.Footnote 73

The streets were a place for productive work and entrepreneurship. Basket weavers, spinners of thread, stocking knitters, lace makers, and other such “cottage” artisans worked in the street.Footnote 74 Boys, of course, made the street a place of play, but many children also found employment there. The ubiquitous boot blacks so often associated with street work do not seem to make an appearance on Rio’s streets until the twentieth century, when less dirt-filled streets made it possible to maintain clean shoes for more than a few minutes, but boys worked delivering goods, running errands, and selling newspapers. Newsboys hawked their wares with one arm raised while the other, with multiple copies of multiple papers tucked in the armpit, carefully guarded the coins in their purses. Boys also comprised the city’s many tattoo artists. This was big business with entrepreneurs hiring, training, and supplying the boys with needles and ink. Each tattoo had a set price, and some were still done, as in Africa, by scarification. One Madruga, who himself had Jesus on his chest, pagan charms on his arms, a snake on his leg, and the initials of his love conquests on his bare shoulders, ran a crew of boys who in a single month tattooed 319 customers. João do Rio reported that nearly everyone in the lower classes, regardless of gender or ethnicity, had tattoos. They were popular with Africans, Jews, Maronites, and Muslims, who received the symbols of their religions, as well as more generally with workers, soldiers, sailors, and peddlers. Pimps tattooed their fists with signs of power; prostitutes had moles placed on their faces. Some tattoos protected one symbolically from unseen evils while others served more directly: one sailor had Christ and the cross placed respectively on his chest and back because they would prevent ship captains and port authorities from giving him a whipping as it would appear “they were thrashing upon Christ.” Women tattooed the initials of former lovers on the soles of their feet, as an act of spite, and some inked their children’s names or initials on their breasts. The Portuguese, who arrived in Brazil with clean skin, soon sought out the tattoo boys whose art was performed publicly on street curbs and fountain steps. Tattoo artists might make as much money as a respectable office clerk.Footnote 75

Rio’s informal economy was made up largely of street workers, not to mention all those engaged in transportation and street maintenance. Jaime Benchimol asserts that even though Rio was Brazil’s industrial center until the 1920s, the ambulantes, as an economic category, were larger than Rio’s industrial class.Footnote 76 The street was a place of work, and as long as the street remained common, it enriched and diversified the city’s economy. For some, like policemen, lamplighters, and slave catchers, the street was merely incidental to their work, but for thousands, the street was essential to gainful employment. Many could not afford to buy or rent private spaces in which to produce or offer their goods and services. The common street made it such that one could be productive. Many peddlers worked for merchants, but some chose the profession because it offered independence. To work anywhere but the street typically meant to work for someone else or at least under someone else’s eyes.