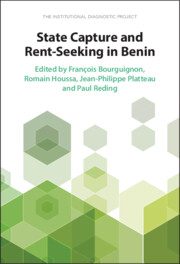

The first part of this volume provided a thorough description of where Benin stands in terms of economic, social, political, and institutional development. Chapter 1 briefly reviewed the country’s deep historical legacies and reviewed its recent political history, insisting on the implications of the tipping-over from the Marxist–Leninist period to the present liberal political and economic regime. Chapter 2 summarised Benin’s main economic development challenges, especially the limitations of the two current major activities, cotton exports and cross-border trade with Nigeria, as potential development engines, the lack of dynamism of the rest of the economy, and the heavy dependence on foreign financing. Benin has underperformed against other sub-Saharan countries, in terms of growth and poverty reduction, over the last twenty years. Given the growth of the population, the prospects for improving Benin’s standard of living and providing decent jobs for newcomers to the labour force in the next twenty years look dim. Chapter 3 focused on the quality of institutions, implicitly seen as an important determinant of the development potential of a country. It reviewed the perceptions held by different types of experts regarding the way institutions work in Benin, pointing to several major weaknesses, most notably a high level of corruption, a dysfunctional public management system, and an excessive degree of informality.

The main points made in those three chapters are closely related. The binding constraints identified in Chapter 2 and in other growth diagnostic exercises have clear roots in existing institutional weaknesses, and the state of institutions is strongly dependent on the political economy of policy making and institutional reform. The three chapters in Part I of this study provided a thorough description of those three aspects of development in Benin, without, except occasionally, really getting into the mechanics that closely link them together. It is now time to do this, in order to establish later on a diagnostic of how the way institutions work in Benin hinders development, and to explore possible directions for reform.

Such an analysis of the complex three-way relationship between political economy, institutions, and economic development cannot be conducted at the aggregate economic level – it would be extremely artificial. Institutions affect economic development through their role in the functioning of sectors or activities, public or private, that are key for economic development. In turn, it is the revenue from these activities and the way it is distributed among actors, whether individual or collective, as well as the relative political power of these actors, that lead to institutions being maintained as they are, or to attempts to reform them. The aim of Part II of the institutional diagnostic aims precisely to understand better this relationship and the central role of institutions in it, through deep-dive analyses of specific economic sectors and political economy practices.

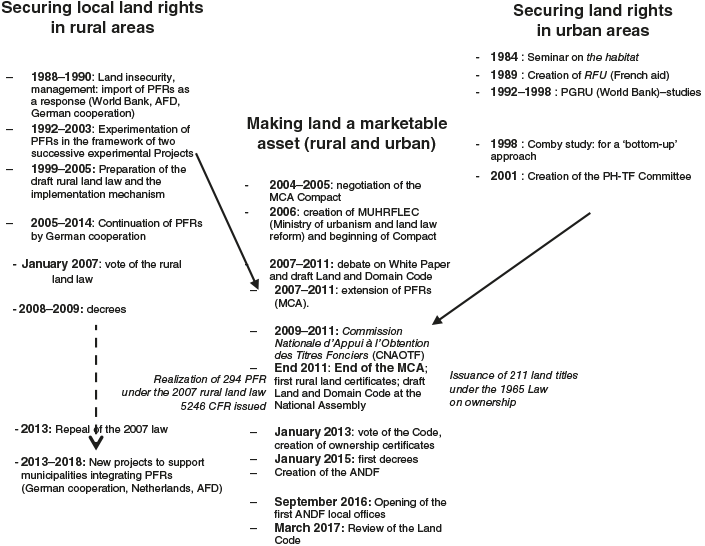

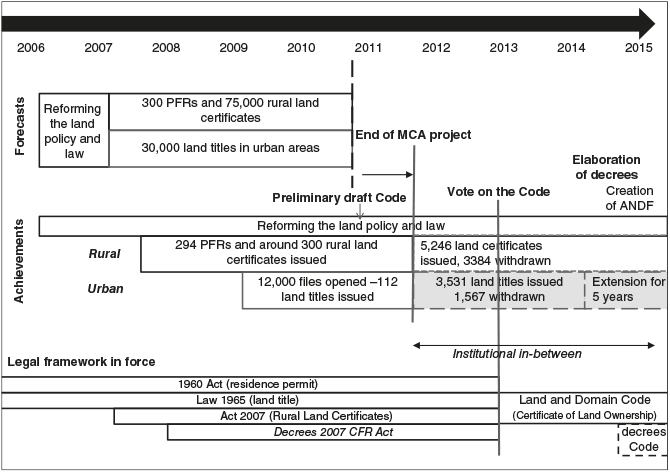

Five thematic studies were undertaken with this objective in mind. The selection of themes was very much guided by the descriptive analysis in the preceding chapters and the major development challenges that it uncovered. Quite naturally, these themes include the functioning of the two major sectors of activity in Benin: cotton production and exports, and the illegal cross-border trade with Nigeria. As far as public management or state capacity is concerned, the choice has been to focus on the tax administration, singled out in many studies as particularly inefficient despite its key role in generating revenues for public investment. The reform of land laws launched in 2013 provides an opportunity for studying an attempt at modifying a key traditional institution in a country with an agricultural comparative advantage and a strong urbanisation drive. Finally, the political economy aspect of economic management, whose crucial importance has been stressed on various occasions in the previous chapters, is approached through a rather original study of the financing of electoral campaigns by the business sector and the rewards offered by politicians to their private sponsors.

The thematic studies are authored by Beninese or foreign scholars with a deep knowledge of Benin. Each study is complemented by a discussion by another scholar, with the aim of broadening the reflection and often bringing to it some knowledge and experience that go beyond Benin.

I Introduction

A large number of studies show that patron–client relationships between politicians and voters deter democratisation and development (Bardhan and Mookherjee, Reference Bardhan and Mookherjee2017; Gallego et al., Reference Gallego, Li and Wantchekon2018; Robinson and Verdier, Reference Robinson and Verdier2013; Stokes, Reference Stokes2005; Stokes et al., Reference Stokes, Dunning, Nazareno and Brusco2013; Wantchekon, Reference Wantchekon2003). However, while most studies focus on the interaction between politicians and voters, and more recently on the role of political brokers,Footnote 1 they often fail to characterise the influence of interest groups, particularly firms, on political distortions.

The consequences of leaving aside the role of firms in studies of patron–client relationships between politicians and voters are twofold. First, by assuming that sponsoring interests and political parties are unified actors that hold the same incentive structure, studies fail to recognise the independent effect of the political connections firms and politicians on governance, particularly on corruption.

Second, the clientelism literature has understudied firms’ strategic decision-making when facing political uncertainty: firms might undermine democratic consolidation – which thrives with electoral uncertainty – through increasing levels of intervention, corruption, and capture. In other words, democracy thrives with electoral uncertainty through political turnover. However, electoral uncertainty also leads to higher financial risk by sponsoring firms.

We show that as electoral uncertainty increases so does the incentive for firms to mitigate financial risk through the appointment of cronies to key government positions, making politicians irrelevant to policy implementation. In other words, increasing risk leads firms to arrange contracts with candidates that replace political intermediaries with direct patrons. Patrons then act as electoral risk-mitigating tools for special interests.

From the latter, demand-side viewpoint, as electoral uncertainty, politicians’ electoral power diminishes vis-à-vis other political contenders, decreasing their bargaining power at the politician–firm contractual arrangement phase, allowing stronger forms of capture.

In that regard, this chapter uses a novel database on contractual arrangements between politicians, political brokers, and businesspeople in Benin to investigate the way the nature of these arrangements depends on the level of political competition. To do so, the chapter pursues four objectives.

First, we propose a reconfiguration of the clientelism and political distortion literature by bringing it together with the ‘political connection’ and clientelism literatures. The cronyism and special interests and lobbying literatures have moved separately from the clientelism literature and have focused on showing, among other things, that political distortions from clientelism are ‘fundamentally different in nature from elite capture’ (Bardhan and Mookherjee, Reference Bardhan and Mookherjee2012, p. 2). With regard to distributional politics, for instance, clientelism is typically progressive, as poor voters are willing to sell their votes at a lower ‘price’. Capture is regressive, as richer interest groups are willing/able to pay more. Moreover, clientelism decreases public goods allocation by favouring private use of public resources, while the implications of capture for public goods remains ambiguous and highly dependent on interest groups’ preference and type. In other words, the special interest literature has stressed that while clientelism and capture represent important forms of political distortion and institutional weakness, especially in developing countries, they are qualitatively different. However, by doing so they have overlooked what politicians do with the financial and non-financial resources provided by firms, and thus they have theoretically misspecified their utility function, and the effect of electoral constraints on firms’ investment maximisation problem. Consider, for instance, that politicians’ strategies of voter mobilisation have to be financed. Thus, campaign finance affects the decision to choose one mobilisation strategy over another.Footnote 2

Second, we characterise empirically the existent firm–politician–broker–voter contractual arrangement, focusing mainly on the relationship between the gifts/resources given to politicians and the different payback demands established by corporations. The chapter uses a novel database on contractual arrangements between politicians, political brokers, and (local and foreign) businesspeople in Benin to investigate the nature of these arrangements and their dependence on the degree of electoral competition. Obtaining information on the underlying ‘sponsoring system’ is difficult, and to our knowledge no study has tried to depict the bilateral relation in terms of resources and pay cheques between firms and national and local politicians. To do this, we carried out structured interviews with key political actors to build a contractual-level dataset covering Benin’s twelve departments and twenty-four electoral districts from 1991 to 2018, for legislative and municipal-level elections. The results allow us to construct national- and local-level contractual arrangements between politicians, political brokers, and firms, including both the financial amounts given to politicians as well as specific concessions granted to interest groups.

Third, we look at determinants of the form of firm–politician contracts. To do so, we consider two alternatives. First, we estimate the effect of political competition as proxied by municipal-level winning margins on firms’ strategic decision-making at the local level, controlling for various cross-municipal socio-demographic differences, surveyor, and municipal fixed effects. To push forward causal identification we provide placebo tests on legislative-level elections. Elections for Members of Parliament (MPs) in Benin provides an ideal placebo, since they do not hold control over national- or regional-level procurement and budgeting, and they have no say in national or regional bureaucratic positions. Contrary to other settings, MPs are not allocated to relevant committees in parliament in charge of budgeting, but rely on party and executive lines for general voting patterns in the assembly. Thus, electoral shocks that modify the overall electoral uncertainty faced by MPs should not lead to firms’ stronger preference for more direct forms of state capture or the appointment of cronies to key government positions. Second, we exploit a quasi-exogenous shock introduced by the 2018 electoral reform that – among other features – collapsed the existent multiparty system into a two-party block competition.Footnote 3 The reform allows us to compare those communes and electoral districts with multiple parties competing for office and suddenly collapsed to one of the two proposed party blocks, decreasing electoral competition (our treatment group), to those districts that were already under a de facto two-party system (our control). Our expectation, later confirmed empirically, is that those districts that experience a decrease in electoral uncertainty experience a decrease in firms’ preference for direct forms of state capture. Both empirical strategies then allow us to observe the existent simultaneity of democratic consolidation – which thrives with electoral uncertainty through political turnover – and special interests’ state capture.

Finally, the fourth objective of the chapter is to contribute to the study of institutional reforms that aim to reduce the influence of interest groups and the negative effects of clientelism in developing countries. In particular, we pinpoint the need for multilevel reforms to prevent business interference, limit bureaucratic capture by brokers, promote transparent appointment processes, and strengthen accountability through the promotion of voter civic engagement in Benin.

In fact, since the democratic renewal of Benin in 1991, political actors have initiated reforms aiming to reduce the cost of campaigning. However, the reforms yield mixed results. The attempts include the following. The first was the imposition of campaign spending caps according to election type (presidential, parliamentary, and local). However, the caps have not been respected or enforced. Furthermore, by 1998, a provision in the electoral code removed the verification capacity of the Supreme Court – the institution in charge of the control of campaign spending of candidates and parties. By 1999 a new electoral restriction was introduced forbidding the distribution of campaign gadgets (T-shirts, caps, pens, etc.) with parties’ and candidates’ logos within six months of national elections (presidential and parliamentarian). The electoral change had mixed results, with parties and candidates utilising specific colours for branding instead of logos. Lastly, a limitation of the campaign period to two weeks was established (contrary to countries where there is no limitation at all like Ghana or where the campaign period is long such as Nigeria’s three months). This restriction is supposed to contribute to the reduction of campaign costs. Except for the incumbent, this measure has seemed to be by and large successful.

It is important to note that Benin has three traits that make it an ideal setting in which to study the relationship between economic and electoral risk and firms’ state capture strategies. First, the dynamics of electoral competition and economic power vary substantially across the country’s seventy-seven communes and twelve departments. The winning margins by political party for the commune-level 2015 elections are substantially low (less than 1 per cent). Moreover, Benin can be characterised as a low concentrated party system in terms of vote share. Moreover, between communes and within communes across time we notice large variability in the actions taken by influence groups to achieve their desired outcomes. Second, Benin provides a case of thriving democratisation mixed with poor governance and various degrees of local state capacity, an important mediator to consider when studying politician–private-sector contracts. Lastly, a pseudo-decentralised political system allows for local politicians to have substantial freedom to shape local campaigns and agree to different contractual arrangements with their financial sponsors.

Our results show three main findings. First, around 34 per cent of mayors and city councils competing for municipal-level positions, and deputies competing for legislative seats, face budget constraints in regard to developing their political campaigns. This creates a need to negotiate their budget deficit with businesspeople in order to run for elections, allowing for contracts through narrow commitment over policies. Second, the most recurrent policy concessions made by businessmen are public procurement arrangements (71 per cent of contracts include such concessions), followed by policy commitments related to firms’ interests (46 per cent of cases), and the direct appointment of businessmen’s relatives to public positions (39 per cent of cases). In part, this rank ordering is due to the fact that public procurement allows for firms to cash in and for politicians to keep a share of the procurement (a minimum of 10 per cent in Benin’s case). Note that policy concessions add more than 100 per cent, which implies that contracts contain more than one concession petition.

Most interesting are firms’ strategic decisions when faced with political uncertainty. If incumbents do not comply with the contract with firms, the latter may finance riots against the former to increase economic concessions and payment. Moreover, firms seek to support challengers with contracts that are characterised by higher concessions, increasing the overall control of firms over local governments and national politics. Regarding the estimation of the effect of winning margins on firms’ capture preferences, we find that a 1 standard deviation increase in winning margin decreases the reliance on more direct forms of state capture by –0.1684 standard deviation for municipal-level elections, a result that is significant to the 1 per cent level and robust to surveyor and municipal fixed effects and socio-demographic controls. However, interestingly, positive and non-significant results are found for MPs’ elections, showing that electoral shocks only have an effect on firms’ capture preferences when political actors are relevant for electoral risk management.

Relative to the status quo concession benchmark, when elections become more uncertain due to the introduction of more challengers, firms modify their demands in relation to incumbents. In particular, they rely more heavily on demanding that incumbents’ platform commitments are similar to firms’ interests during the electoral campaign (a prevalence of 68 per cent), while decreasing the proportion of public procurement petitions to 67 per cent, holding second place, followed by an increase in pushing forward the political careers of businessmen’s acquaintances, which reaches an occurrence of 64 per cent. Moreover, in this case of higher electoral uncertainty the influence and control over the recruitment in all public sectors increases from 17 to 51 per cent. Lastly, in the absence of what firms consider a ‘good’ candidate to fund, firms increase their participation in elections by running for election themselves.

These results are tied to those on the effect of Benin’s 2018 electoral reform on party collapse in that electoral uncertainty drives firms’ capture preference. In particular, multiparty districts affected by the reform show a decrease of –0.259 standard deviation on firms’ capture preferences in the 2019 commune-level elections. In other words, as the number of candidates decreases – and thus the cost of bribes – firms rely less heavily on more direct forms of state capture, such as the appointment of firms’ agents or cronies to key government positions. Specifically, firms decrease their use of patronage to move forward the political careers of friends and family members (decrease of –0.437 standard deviation), they decrease their use of patronage of members from the company (–0.436), and they reduce the demands on bureaucratic recruitment control (–0.606). The results are robust to including controls on politician-level characteristics, as well as commune fixed effects. Moreover, we demonstrate that the sample of politicians used show a balance on multiple covariates between districts that hold multiparty competition in the 2015 elections (the treatment) to those with de facto two-party competition (the control). While this balance does not rule out commune- and firm-level differences between treatment and control, they show that the results are not driven by sample selection bias. As with the effect of winning margins on firms’ capture preferences, we also find positive and non-significant effects for legislative-level elections, which provides an important placebo to take into consideration.

We believe that differentiating sponsoring interest groups, politicians, and voters will lead to interesting developments in the clientelism literature. First, this chapter provides an explanation of the coordination between politicians and private interests in order to marginalise poor voters, especially in the face of increasing demands for redistribution. Second, it makes it possible to explain the paradoxical result of stronger degrees of direct involvement of interest groups through personal nominations in highly democratised (i.e. highly uncertain) settings. Third, the chapter helps increase our understanding of the variation in strategic decision-making of interest groups between different levels of uncertainty across time and space, either caused by variation in electoral risk or interest groups’ risk. In the spirit of Kitschelt and Wilkinson (Reference Kitschelt and Wilkinson2007), where politicians prefer to use clientelism when they can predict voters’ electoral conduct and elasticity, interest groups prefer to rely on direct capture strategies when uncertainty is high, and they rely on sponsoring political campaigns only when politicians can predict voters’ behaviour well. This point is closely related to the literature on the link between economic and political structural conditions and strategic choices made by firms to mobilise citizens (Diaz-Cayeros et al., Reference Diaz-Cayeros, Estevez and Magaloni2016; Magaloni et al., Reference Magaloni, Diaz-Cayeros, Estevez, Kitschelt and Wilkinson2007).

This chapter is closely related to work on mapping de facto institutions. Starting with Dahl’s (Reference Dahl1961) description of the power structure in New Haven and moving to more recent literature on family networks and politicians (for example, Cruz et al., Reference Cruz, Labonne and Querubin2017; Querubin, Reference Querubin2016), there has been a need to characterise the full power dynamics affecting electoral politics. Moreover, this chapter speaks directly to the large literature on interest groups and cronyism. The crony governance literature focuses on systems in which economic policies are chosen with the goal of benefiting connected actors (Klor et al., Reference Klor, Saiegh and Satyanath2017). Our study, in contrast, focuses on showing how interest groups develop crony networks in local institutions as the degree of uncertainty increases. Most importantly, this chapter connects the seemingly distant but actually highly related literatures of clientelism and cronyism, showing that electoral risk encountered in clientelism settings affects firms’ (sponsors’) strategic decisions to create and fund networks in high-level bureaucratic and political positions.

This chapter is more closely related to the literature on elite capture of local institutions in developing countries. Ch et al. (Reference Ch, Shapiro, Steele and Vargas2018), for example, show that illegal armed interest groups in Colombia – both left-wing guerrilla forces and right-wing paramilitary groups – shaped policy outcomes by influencing local officials who implemented the groups’ policy preferences. Likewise, Sanchez-Talanquer (Reference Sanchez-Talanquer2018) and Pardelli (Reference Pardelli2018) find that landowners transform local institutions in their favour by appointments to key local bureaucracy and political positions, which result in pushing forward beneficial policies in terms of taxes, property rights, and property land values, and increase the relative power of local governments vis-à-vis higher levels of government. This chapter shows how firms use various strategies to control local institutions, and not only promote policy change through violence (as in the case of Colombia), policy change, political campaign sponsoring, or direct appointments to bureaucratic positions.

II Theory and Testable Hypotheses

Consider Anderson et al.’s (2015) clientelistic relationship analysis in India, where elite minorities can undermine policies that push forward redistribution in favour of the poor majority. In this case, the capture mechanism runs through land ownership dominance and the use of cultural hierarchies to achieve political control. However, while empirical evidence shows that elites undermine democracy even in a non-coerced setting, the existent strategic relationship between firms and politicians is not clearly described and is actually not considered. There could be at least two possible types of relationships between firms and politicians, depending on the source of uncertainty. First, politicians could renege on delivering investments to sponsors. Under this setting firms face uncertainty due to politicians’ type, which allows a cheap-talk strategic setting: politicians act as agents who hold a private information advantage in respect to their sponsors or the principal, and ‘bad’ politician types renege on their contractual arrangement or benefit from their advantageous information standpoint. Second, firms might face uncertainty coming not from politicians’ type but from the political environment and institutional design. From a supply-side standpoint – that is, from the perspective of political sponsors like firms – high electoral competition leads to high risk on campaign financial investments. As a response to higher financial risk, firms increase their demand for more direct forms of capture, moving from procurement demands to requesting political appointments and recruitment bureaucratic control. Cronies are then selected for such positions, bypassing politicians entirely.

From a demand-side standpoint, high electoral competition implies politicians’ bargaining power is weaker at the time of negotiating the terms and conditions of the contractual arrangements with firms. Not only is there at least one other candidate with similar electoral strength that could compete for funding, but electoral competition increases both the marginal cost of a vote as well as total campaign costs. The result is needy politicians facing risk-averse firms who move to stronger preferences for direct forms of state capture through the appointment of key government positions.

What does the contract look like? Sponsors fund politicians in order to receive a payback. The payback takes a wide range of forms, running from more indirect to more direct forms of state hijacking: refunds on financial investment, policies and platform changes, public procurement, control of budget lines, patronage, and bureaucratic recruitment control.

III Data and Methodology

To test how political competition affects firms’ uncertainty and modifies their preference for more direct forms of state capture, we study the relationship between international and domestic companies and electoral politics at various levels of aggregation – national and local – in Benin, covering all elections from 1991 to 2019. Benin exemplifies a thriving nascent democracy, with poor governance and economic performance. While being what has been labelled a successful democracy, Benin has been characterised by a high level of corporate capture of local and national politics. As noted by Fujiwara and Wantchekon (Reference Fujiwara and Wantchekon2013), the country’s institutional development has allowed for clientelistic promises to narrow groups of citizens and has favoured private use of local government resources. Benin contains over 3,000 villages (called quartiers) in seventy-seven communes, and they vary widely in the type of productive activities carried out, as well as in the political competition in a multiparty system.

Our methodology exploits two sources of variation. First, variation in firms’ political investment or contractual choice. To measure this, we rely on a novel database on contractual arrangements between politicians, political brokers, and firms in Benin. In particular, we carried out structured interviews with key players, including campaign managers, CEOs of politically connected firms, local brokers, and politicians and candidates, among others.Footnote 4 The result is a dataset with a sample of more than 300 Beninese politicians (deputies, ministries, mayors, etc.), as well as political brokers, covering Benin’s twelve departments and seventy-seven communes.

The data collection took place in Beninese constituencies with targeted populations from 6 February to 21 February 2019. Given the difficulty in identifying potential subjects to survey, a snowball sampling technique (or chain-referral sampling) was used. This is a non-probability sampling technique where existing politicians surveyed recruited future subjects from among their acquaintances. Prior to the interviews, the controller – in charge of coordinating interviews – arranged an appointment with the politician via a phone call to establish contact between the latter and the enumerators to prepare the interview. Then, enumerators met the politician alone, or in a team of two or three, depending on the category (national or local) and/or the agenda of the politician to conduct the interviews. Overall, 311 political actors and brokers were surveyed: 256 politicians, including 191 local politicians (mayors, councillors, etc.), and 83 national politicians (deputies, ministries, cabinets staff, etc.), with 18 who have run for both local and national positions, and 55 brokers (18 per cent of the full sample). Given that elections were scheduled for March and April 2019, we were able to acquire information on contemporary campaigns as well as past ones since 1991. Of the full sample, 76 per cent were running as candidates for the next elections. This dataset allowed us to depict existent politician–firm contracts (such as funding amounts and sources, for instance) and contract types, ranging from those that demand policy and procurement concessions from politicians, to those that seek to influence political platforms during campaign periods, and those that seek to influence direct appointments of firms’ acquaintances, or direct intervention through control of budget lines or key bureaucratic positions.

It is important to note some overall characteristics of the politicians in the database. First, 54 per cent of the 215 surveyed individuals who were running for the next election were running for municipal-level elections, while the rest were competing for legislative ones. On average, individuals are 47 years of age and hold a high variety of education degrees, especially high-level ones, with the majority having either undergraduate or graduate degrees. Moreover, only 27 per cent are first-time runners and those who have recurrently participated in elections in the past have participated in a large number of different types of elections, from commune- to presidential-level ones. It is important to note that Benin is characterised as a highly dynamic electoral setting: more than half of the surveyed politicians have switched political parties. A wide majority have switched not due to opposition to their former political parties, but in opposition to party platform changes. In other words, the highly dynamic party system hides a seemingly conservative underlying ideology spectrum. Noteworthy, additionally, is the fact that almost all politicians and political brokers (87 per cent) are members of a political party. Lastly, it is important to see that of the full sample, 36 per cent say they have held private positions in the past.

The second source of variation we exploit is national and local variation in electoral uncertainty. We rely on two measures of electoral uncertainty: first, the use of winning margins; second, the number of political candidates contending for office. We believe the former constitutes a benchmark measure of electoral competition, given that winning margins are positively related to a candidate’s likelihood of winning office or the risk associated with a candidate losing. Related to the latter, as the number of political candidates increases, so does the total amount of bribes that firms need to allocate in order to achieve their desired policy preference. In other words, the number of candidates represents a cost of contractual arrangements. Both the costs and electoral competition form part of what we define as electoral uncertainty in this particular setting. As an example, the highest level of electoral uncertainty will be that where low winning margins coincide with a plethora of political candidates running for office with relatively equal electoral strength.

For identification we rely on two empirical tests, given these two sources of variation, firms’ preferences for direct capture and electoral uncertainty. First, we analyse the relationship between winning margins and firms’ state capture preferences as stated in contractual arrangements. In particular, we estimate the following ordinary least squares (OLS) specification:

where yd is either a dummy of any of the preferences for state capture or intervention pushed by firms on politicians, including demanding a refund of resources, and demanding policy and programme modification during a campaign; demanding support for future candidates close to firms; demanding a local budget line; demanding public procurement; patronage both for close family members and for friends or members of the firm; and taking control of bureaucratic recruitment control in a district d; Winning Margind is a continuous variable on the winning margin of the incumbent relative to the second contender for the 2015 commune-level elections; Xd is a vector of commune-level control variables;Footnote 5 and Wi is a vector of politician-level characteristics, listed in Table 4.1, including age, education, title, former occupation, political experience, a dummy to account for party switch and reasons for such a switch, and electoral political experience as candidates in different types of elections. We also include a district fixed effect, γd, to account for any district-level time-invariant heterogeneity. Thus, our estimates account for the change in firms’ preferences for direct forms of state capture in districts that have experienced high electoral uncertainty, as proxied by smaller winning margins. We report robust standard errors (SEs) throughout, clustered at the electoral district level.Footnote 6

Table 4.1 Balance table, list experiment on politicians’ affiliation with firms

| Mean control | Mean treatment | Diff. | Diff. SE | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title: politician (=1) or broker (=0) | 0.836 | 0.796 | 0.04 | 0.047 | 0.395 |

| Deputy | 0.047 | 0.071 | –0.024 | 0.028 | 0.379 |

| Minister | 0.005 | 0 | 0.005 | 0.007 | 0.498 |

| Mayor | 0.066 | 0.02 | 0.045 | 0.027 | 0.093 |

| Municipal council member | 0.333 | 0.306 | 0.027 | 0.057 | 0.635 |

| Cabinet director | 0.005 | 0.031 | –0.026 | 0.014 | 0.06 |

| Other | 0.545 | 0.571 | –0.027 | 0.061 | 0.66 |

| Age | 49.286 | 44.122 | 5.164 | 1.314 | 0 |

| Years living in region | 38.756 | 35.122 | 3.633 | 2.096 | 0.084 |

| No education | 0.019 | 0.01 | 0.009 | 0.015 | 0.578 |

| Elementary | 0.038 | 0.02 | 0.017 | 0.022 | 0.427 |

| College 1st cycle | 0.15 | 0.041 | 0.109 | 0.039 | 0.005 |

| College 2nd cycle | 0.155 | 0.122 | 0.032 | 0.043 | 0.451 |

| University 1st cycle | 0.169 | 0.153 | 0.016 | 0.045 | 0.725 |

| University 2nd cycle | 0.254 | 0.367 | –0.114 | 0.055 | 0.04 |

| Graduate | 0.216 | 0.286 | –0.07 | 0.052 | 0.181 |

| Member of political party | 0.967 | 0.98 | –0.012 | 0.021 | 0.544 |

| Participated in elections as candidate | 0.751 | 0.643 | 0.108 | 0.055 | 0.049 |

| Participated in commune-level elections | 0.881 | 0.857 | 0.024 | 0.049 | 0.627 |

| Participated in legislative-level elections | 0.362 | 0.397 | –0.034 | 0.072 | 0.635 |

| Participated in presidential-level elections | 0.013 | 0.016 | –0.003 | 0.017 | 0.845 |

| No. of participations in commune elections | 1.5 | 1.429 | 0.071 | 0.127 | 0.575 |

| No. of participations in legislative elections | 0.562 | 0.651 | –0.088 | 0.141 | 0.531 |

| No. of participations in presidential elections | 0.006 | 0.063 | –0.057 | 0.041 | 0.163 |

| Party switch | 0.476 | 0.625 | –0.149 | 0.109 | 0.17 |

| Party switch 2 | 0.739 | 0.667 | 0.072 | 0.141 | 0.61 |

| Ideology reason | 0.439 | 0.595 | –0.155 | 0.071 | 0.029 |

| Poor project definition | 0.291 | 0.365 | –0.074 | 0.066 | 0.263 |

| Personal interest | 0.534 | 0.432 | 0.101 | 0.071 | 0.156 |

| Opposition to movement | 0.568 | 0.514 | 0.054 | 0.071 | 0.448 |

| Movement towards opposition | 0.149 | 0.149 | 0 | 0.051 | 1 |

| Running for next elections (2019) | 1.319 | 1.286 | 0.034 | 0.057 | 0.554 |

| Running for commune elections (2019) | 0.724 | 0.671 | 0.053 | 0.066 | 0.429 |

| Running for legislative elections (2019) | 0.414 | 0.514 | –0.1 | 0.072 | 0.166 |

| Running for presidential elections (2019) | 0 | 0.029 | –0.029 | 0.014 | 0.041 |

| First-time runner | 0.255 | 0.3 | –0.045 | 0.065 | 0.49 |

| Holds political position | 0.779 | 0.724 | 0.055 | 0.052 | 0.293 |

| Holds private position | 0.352 | 0.388 | –0.036 | 0.059 | 0.545 |

Note, however, that this specification does not allow us to rule out time-variant and other sources of potential endogeneity. To push forward the identification we estimate equation (1) for municipal-level elections and run a placebo test on legislative-level elections. Elections for MPs in Benin provide an ideal placebo, since MPs do not exercise control over national- or regional-level procurement and budgeting, and they have no say in national or regional bureaucratic positions. In contrast to other settings, MPs are not allocated to relevant committees in parliament in charge of budgeting, but rather they rely on party and executive lines for general voting patterns in the assembly. Thus, electoral shocks that modify the overall electoral uncertainty faced by MPs should not lead to firms’ stronger preference for more direct forms of state capture or the appointment of cronies to key government positions.

As a second identification strategy, we use quasi-exogenous variation introduced by the electoral reform in Benin in 2018, which collapsed the multiparty system to an effective two-party block competition.

The reform allows for the existence of multiple parties, but forces parties to join a block to compete, and no more than two blocks can contend for any political position in the country. The reform allows us to compare those communes (or seats) that had multiple parties competing for office and higher degrees of electoral competition and suddenly were affected by the reform (our treatment group) to those communes that already had an effective two-party system (our control). The expectation is that communes affected by the electoral reform reduce the number of effective political parties and thus candidates, decreasing the overall financial costs of bribery faced by sponsoring firms, making them less desirous of more direct forms of state intervention. Interestingly, the number of candidates is highly negatively correlated with the winning margin, and positively correlated with voter turnout for the commune-level 2015 elections (see Figures 4.A.1a–4.A.1d in the Appendix). Thus, while we believe that the effective number of parties (and candidates) acts as a proxy for the capture costs of firms, it also represents an indirect measure of electoral competition, and thus electoral uncertainty. In short, for the identification of the effect of contract type we will rely on cross-municipal competition variation triggered by quasi-exogenous shocks in electoral competition. Specifically, we estimate an OLS specification at the electoral district level for commune-level elections on the effect of the electoral reform as a quasi-exogenous shock to electoral uncertainty on firms’ strategic capture of government in the current 2019 elections:

where yd is a dummy for any of the demands pushed by firms on politicians, including demanding a refund of resources, demanding policy and programme modification during the campaign, demanding support for future candidates close to firms, demanding control over the local budget line, demanding control over public procurement, demanding patronage both for close family members and for friends or members of the firm, and taking control of bureaucratic recruitment control in a district d; Electoral Reformd is a dummy that takes a value of 1 if a commune-level electoral district had more than 2.5 effective parties, as measured by a Molinar Index for the 2015 commune-level elections, and 0 otherwise;Footnote 7 Xd is a vector of commune-level control variables;Footnote 8 and Wi is a vector of politician-level characteristics, listed in Table 4.1, including age, education, title, former occupation, political experience, a dummy to account for party switch and reasons for such a switch, and electoral political experience as candidates in different types of elections. We also include the district fixed effect, γd, to account for any district-level time-invariant heterogeneity. We are thus working with between-electoral district variation in firms’ government capture, controlling for a range of district- and politician-level characteristics. Hence, our estimates account for the change in firms’ strategies in districts that experienced less electoral uncertainty than the electoral districts mean. We report robust standard errors throughout, clustered at the electoral district level, as done with equation (1).Footnote 9

For both equations (1) and (2) we construct a firm capture index with all available demands made by firms in their contractual arrangements with politicians. The index ranges from 0 to 6, with 6 being the highest degree of capture. In particular, capture demands are categorised in the following way: financial refunds get a value of 0; policies and programme changes a value of 1; support for future candidates close to firms’ interests a value of 2; control of a budget line a value of 3; public procurement a value of 4; patronage 5; and, lastly, bureaucratic recruitment control a value of 6. We believe this ordering fits well the notion of increasing capture in firms’ actions as depicted in the Beninese study case.

Our identifying assumption with this approach is that electoral uncertainty variation occurs due to a quasi-exogenous shock conditionally independent from future firms’ capture demands. Our controls tease out district-level dynamics, especially pre-treatment competition levels. One concern, however, is that this approach could simply pick enduring cross-sectional within-electoral district differences, correlated with both electoral uncertainty and firms’ demands. To rule this out we include a set of regressions controlling for firms’ demands in the 2015 election and identify whether pre-treatment demand differences between control and treatment districts are non-existent.Footnote 10 Furthermore, we show that sampled politicians in treatment and control districts do not have statistically different characteristics.Footnote 11 This gives high confidence regarding avoiding sample selection bias, as well as treatment and control similarity. Lastly, as done with the estimation of equation (1), we use MPs’ elections as a placebo test.

A Descriptive Statistics on Campaign Funding

In this section, we provide a short description of the data, based on the preliminary descriptive statistics related to the central tendency of key variables of the study. This is followed by a short discussion. At a first glance at the data we notice that businessmen invested, on aggregate, a total of CFA Franc 7,567,560,000 (US$13,080,443) in the recent electoral campaigns as financial support to politicians, according to the 189 who responded to this question. On average, the former invested, all elections combined, an amount of CFA Franc 40,040,000 (US$69,252) in the campaigns of a candidate. Considering the type of elections and the location, the financial package is about CFA Franc 10,900,000 (US$18,838) and CFA Franc 47,600,000 (US$82,288) for municipal elections, respectively, in rural and urban areas. These figures are higher according to the importance of elections. For instance, CFA Franc 37,300,000 (US$64,470) and CFA Franc 67,600,000 (US$116,842) are invested in legislative campaigns of a candidate in rural and urban locations, respectively.

While political parties’ charters predict CFA Franc 1,500,000 (US$2,592) and CFA Franc 30,000,000 (US$51,853) for municipal and legislative campaigns, out of the 27 per cent of those who really know these amounts, 34 per cent find it insufficient for the corresponding elections, including those who ran or will run for commune and legislative elections. Note, however, in Figure 4.1a that those who believe politicians have a ‘reasonable amount of funding’ or ‘more than needed’ greatly surpass the campaign costs of those that believe funds are insufficient.

Figure 4.1a Campaign cost by type of election and evaluation of funds

Actually, as noted in Figure 4.1b, we see that those who believe that ‘campaign funds are reasonable or more than needed’ believe that campaign costs should be decreased substantially, especially in commune-level elections. Subsequently, on average, they reported CFA Franc 115,000,000 (US$198,772) and CFA Franc 163,000,000 (US$281,691) as the amount necessary for legislative elections in rural and urban constituencies, respectively.

Figure 4.1b Ideal vs real campaign costs, by election type and evaluation of funds

Furthermore, business monetary involvement in electoral campaigns is substantial. Figures 4.2a–4.2b show a striking result: for commune-level elections, firms account for 54.3 per cent of the total campaign costs on average. More impressive is the fact that 15.7 per cent get funding from businesses that surpass the total campaign costs, sometimes holding budgets up to three to four times more than needed. These results are even greater for legislative-level elections, with firms accounting for 76.3 per cent of total campaign costs.Footnote 12 In other words, as we move up the federalist ladder in Benin we notice more business intervention in monetary terms.

Figure 4.2a Ratio of firms’ funding to campaign costs by type of election: Community level

Figure 4.2b Ratio of firms’ funding to campaign costs by type of election: Legislative level

IV Results

The former evidence points to the high intervention of businessmen in elections at different levels. However, the actual proportion of politicians affiliated with firms suffers from social desirability bias and thus politicians might not truthfully answer sensitive questions, creating a measurement challenge. Moreover, given the complexity of businessmen’s interests, it is difficult to capture such dynamics either observationally or through surveys.

One way to address such challenges is the use of a list experiment. As noted by Blair and Imai (Reference Blair and Imai2012) and a large range of studies (Biemer et al., Reference Biemer, Jordan, Hubbard, Wright, Kennet and Gfroerer2005; Gonzalez-Ocanto et al., 2010; Jamison et al., Reference Jamison, Karlan and Raffler2013; Kane et al., Reference Kane, Craig and Wald2004; Kuklinski et al., Reference Kuklinski, Sniderman and Knight1997), this methodology protects respondents’ confidentiality, allowing them to reveal sensitive information. The underlying mechanism in a list experiment is to compare two groups: a treatment and a control group. The control group is asked to report the number of non-sensitive items called a short list, while the treatment group is asked to report the number on that same short list plus an additional sensitive item. The average response for each group is estimated and differenced out. The difference in means represents the proportion of the population for whom the sensitive item applies. Design effects are tested, as well as ceiling and floor effects, to validate the list experiment estimate (for details, see Ch et al., Reference Ch, Hounkpe, Wantchekon, Bourguignon, Houssa, Platteau and Reding2019).

Specifically, the list experiment question tested to measure politicians’ affiliation to business interests was the following:

How many of the following five individuals or groups do you consider yourself politically affiliated with? Please indicate HOW MANY in total: I don’t want to know which ones, only how many of them.

The list of answers that the control groups received included:

the mayor of this commune;

a member of the communal council;

the prefect of this department;

the MP; and

the president/president’s political party.

The list that the treatment group received included the following sensitive item (in the sixth position on the list):

national or local businessman/firm/business group.

In order to separate respondents into the treatment and control groups, we used their birthday months. Those born in January, March, May, July, September, and November were assigned to the control group, while those born in February, April, June, August, October, and December made up the treatment group.

Table 4.1 shows the balance between the treatment and control groups of the list experiment across a wide range of covariates on politician characteristics. Out of thirty-eight covariates we notice a significant difference in four, giving us confidence regarding the balance to the 10 per cent level.

Table 4.2 shows the results of the list experiment by running a t-test comparing the treatment and control means on politicians’ affiliation with firms’ interests. The difference shows a prevalence of firms’ interests of 48.1 per cent, a difference significant to the 1 per cent level. In other words, almost half of politicians and political brokers in Benin are affiliated with either local or national business interests.

Table 4.2 List experiment: Politicians’ affiliation with local and national business interests

| Mean control | Mean treatment | Diff. | Diff. SE | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affiliation with firm/business interest | 3.54 | 4.02 | −0.481 | 0.167 | 0.004 |

| Commune/municipal elections: Affiliation with firm/business interest | 3.576 | 4.406 | −0.83 | 0.275 | 0.003 |

| Legislative elections: Affiliation with firm/business interest | 3.683 | 4.139 | −0.456 | 0.281 | 0.109 |

If we distinguish by election type, we notice that business affiliation is higher in commune municipal elections, with a proportion of 83 per cent, significant to the 1 per cent level. Legislative elections show a lower proportion, of 45.6 per cent, with a significance barely reaching 10 per cent. In other words, as we move up the administrative ladder, we notice a decrease in business intervention. A plausible explanation to explore in the future is that business interference might be higher at lower administrative levels due to national government lack of monitoring and state capacity.

It is important to compare these results with those shown in Table 4.3. This table presents a list of different sources of funding provided to politicians for commune and legislative elections. Numbers represent the percentage of funds coming from a particular source. Related to business interests we note that firms, local and national, account for 16 per cent of total funding at the commune level and 17 per cent for legislative elections. Both estimates contrast significantly with the results of the list experiment, showing the effect of social desirability bias.Footnote 13

Table 4.3 Clientelist contracts – descriptive statistics

| Mean | SD | Min | Max | N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Firm–politician contract | |||||

| Sources of funding: Commune level | |||||

| National funding | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0 | 0 | 117 |

| Department funding | 0 | 0.02 | 0 | 0 | 117 |

| Party/party coalition funding | 0.31 | 0.26 | 0 | 1 | 117 |

| President/president’s party funding | 0.21 | 0.27 | 0 | 1 | 117 |

| Local firms funding | 0.1 | 0.11 | 0 | 0 | 117 |

| National firms funding | 0.06 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 117 |

| Local politicians funding | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0 | 1 | 117 |

| Local/national unions funding | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0 | 0 | 117 |

| Percentage coming from others | 0.39 | 0.26 | 0 | 1 | 75 |

| Sources of funding: Legislative level | |||||

| National funding | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0 | 1 | 96 |

| Department funding | 0 | 0.01 | 0 | 0 | 96 |

| Party/party coalition funding | 0.31 | 0.24 | 0 | 1 | 96 |

| President/president’s party funding | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0 | 1 | 96 |

| Local firms funding | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0 | 1 | 96 |

| National firms funding | 0.08 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 96 |

| Local politicians funding | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0 | 0 | 96 |

| Local/national unions funding | 0 | 0.02 | 0 | 0 | 96 |

| Percentage coming from others | 0.38 | 0.27 | 0 | 1 | 63 |

| Types of funding: Commune level | |||||

| Financial instruments | 0.78 | 0.42 | 0 | 1 | 117 |

| Goods/non-financial services | 0.56 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 117 |

| Economic/political advisers | 0.23 | 0.42 | 0 | 1 | 117 |

| Labour for campaign | 0.35 | 0.48 | 0 | 1 | 117 |

| Provision of space | 0.45 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 117 |

| Support for advertisement | 0.49 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 117 |

| Other forms of financing | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0 | 1 | 117 |

| Types of funding: Legislative level | |||||

| Financial instruments | 0.82 | 0.38 | 0 | 1 | 96 |

| Goods/non-financial services | 0.65 | 0.48 | 0 | 1 | 96 |

| Economic/political advisers | 0.25 | 0.44 | 0 | 1 | 96 |

| Labour for campaign | 0.48 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 96 |

| Provision of space | 0.46 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 96 |

| Support for advertisement | 0.44 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 96 |

| Other forms of financing | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0 | 1 | 96 |

| Firm–politician contract | |||||

| Payback time: Commune level (=1 after election, 0=before) | |||||

| Policies | 0.71 | 0.46 | 0 | 1 | 49 |

| Public procurement | 0.63 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 | 91 |

| Patronage | 0.55 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 47 |

| Patronage from firm | 0.33 | 0.48 | 0 | 1 | 45 |

| Support future candidate | 0.47 | 0.51 | 0 | 1 | 17 |

| Programme modification | 0.5 | 0.52 | 0 | 1 | 12 |

| Refund | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Recruitment control | 0.26 | 0.45 | 0 | 1 | 19 |

| Budget line | 0.4 | 0.55 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| Payback time: Legislative level (=1 after election, 0=before) | |||||

| Policies | 0.79 | 0.42 | 0 | 1 | 42 |

| Public procurement | 0.68 | 0.47 | 0 | 1 | 73 |

| Patronage | 0.62 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 | 37 |

| Patronage from firm | 0.47 | 0.51 | 0 | 1 | 40 |

| Support future candidate | 0.58 | 0.51 | 0 | 1 | 19 |

| Programme modification | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Refund | 0.33 | 0.52 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| Recruitment control | 0.33 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 | 12 |

| Budget line | 0.5 | 0.55 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| Politician–voter contract | |||||

| Commune level | |||||

| Mass communication policy and agenda | 0.95 | 0.22 | 0 | 1 | 117 |

| Political appointments | 0.38 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 | 117 |

| Vote-buying attempt | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 117 |

| Non-conditional transfer (NCT) | 0.24 | 0.43 | 0 | 1 | 117 |

| Ethnic strategy | 0.44 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 117 |

| Legislative level | |||||

| Mass communication policy and agenda | 0.9 | 0.31 | 0 | 1 | 96 |

| Political appointments | 0.42 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 96 |

| Vote-buying attempt | 0.53 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 96 |

| NCT | 0.38 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 | 96 |

| Ethnic strategy | 0.4 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 | 96 |

A Contracts between Firms and Politicians

A wide variety of types of funding types characterise the contract between firms and politicians in Benin. As noted in Table 4.3, firms hold a wide range of resources available for politicians. Besides the primacy of financial instruments and non-pecuniary goods and services provided by firms, politicians utilise advisers and labour to support their political campaigns. A large proportion of politicians (45 per cent for commune elections and 46 per cent for legislative ones) also utilise space provided by firms for their political campaigns.

Most interestingly, the results show that public procurement arrangements have a prevalence in firm–politician contracts of 71 per cent, followed by policy commitments narrowed down to businessmen’s interests with a proportion of 46 per cent. In third place comes the appointment to public positions of businessmen’s relatives or people they suggest. Depending on the type of elections, this appointment could be in the local administration as an office head or as a member of the central government (ministry, cabinet chiefs, etc.), with a proportion of 39 per cent. These are the most preferred means for businessmen to recover what they have invested in candidates’ electoral campaigns and to ensure their control over the implementation of policies. In other words, these numbers should be considered the country’s baseline actions by firms.

According to the respondents, businessmen prefer public procurement overall, because of the direct cash flows it generates. Interestingly, they place it in first place because it is also a means for incumbents to make money as they find a way to keep a minimum of 10 per cent of the total amount for themselves, in agreement with the businessmen. It is worth emphasising that the amounts of these public procurements are sometime tenfold greater or even more than the money invested by the businessmen, and it may happen that they execute more than three to five projects during their tenure.

A good illustration of procurement and how effective it is for both actors is the recent scandal involving the building of a new national assembly in Benin: between two offers, one from a Chinese company that is accredited and well recognised for its insight and expertise in the domain, with a value of CFA Franc 14,000,000,000 (US$24,194,397), and another from a national company affiliated with government officials, with a value of CFA Franc 18,000,000,000 (US$31,107,082), the government attributed the procurement to the latter, representing an overspend of CFA Franc 4,000,000,000 (US$6,914,643), which is twice the amount invested by the businessman to support the presidency of the Beninese former President Boni Yayi. Interestingly, this represents tenfold the money (CFA Franc 400,000,000, so US$691,464) the same businessman invested to support the legislative campaigns of a candidate. From these examples it appears clear why businessmen prefer public procurement over the narrow implementation of policies and the appointment of relatives, which might take a bit longer to yield the expected results.

B Contracts between Politicians and Voters

On the contracts between politicians and voters, politicians apply a wide range of strategies to increase public support. As Table 4.3 shows, a large proportion of politicians and political brokers use non-programmatic strategies: half of politicians in commune-level elections utilise vote-buying attempts, while 38 per cent rely on promising political appointments, and 24 per cent use non-conditional transfers to citizens. For legislative elections these numbers increase to 53 per cent for vote-buying attempts, 42 per cent for political appointment promises, and 38 per cent for non-conditional transfers. In the context of Benin, the use of ethnic strategies surges as an important strategy for promoting voter support. Ethnic strategies mostly target promoting policies that benefit the in-group instead of the out-group.

C Political Uncertainty and Firms’ Strategic Decision-Making

If it happens that incumbents do not comply with the deal they have made with businessmen, the latter may finance riots against the former. Sometimes aided by state institutions, firms’ actions affect politicians’ political careers by either causing them to lose future elections or reducing their winning margin. The most noted strategy utilised by businessmen if politicians do not comply with what was specified in the contract is to support challengers who allow for more concessions than the previous politicians, increasing firms’ state capture. In this regard, when the number of candidates increases, businessmen support all potential candidates to avoid wasting money, and to ensure the sustainability of their particular interest.

With more challengers, businessmen’s preferred state capture strategy order changes: modification of incumbents’ platform commitments to align with businessmen’s interests during the electoral campaign, with a proportion of 68 per cent, ranks first, instead of public procurement, which comes in second place, with a proportion of 67 per cent, followed by the promotion of the political careers of the relatives of businessmen, with a proportion of 64 per cent. It is also important to emphasise that from a proportion of 17 per cent, influence and control over recruitment in all public sectors related to the economy increases to 51 per cent, one of the strongest strategies, if not the strongest, of state capture at the local and national level.

Table 4.4 tests the change in the use of capture strategies of firms for commune/municipal elections. The table reports a t-test on the difference in means between the strategies used under a high electoral competition setting, as proxied by a hypothetical increase in the number of candidates contending (the treatment group), to the strategies used under a low electoral competition scenario with few candidates contending for office (the control group). While the results should be interpreted only as simple correlations, they show interesting dynamics. As noted before, procurement increases dramatically, with an increase of 10.9 per cent significant to the 1 per cent level, while other forms of lower capture value decrease, particularly the demand for political programme changes, which falls by 7.7 per cent, significant to the 1 per cent level. While non-significant, we see a positive increase in all those strategies involving high degrees of state capture, including patronage (increase of 16), bureaucratic recruitment (10 per cent), and the demand to control the budget line (0.6 per cent). We also note an overall decrease in all the strategies associated with low degrees of state capture or with a null effect on state capture, with a decrease in policy demands (−2.3 per cent), demanding support for a candidate supported by the firm in the future (−1.6 per cent), or asking for a refund on what was invested in the politician (−2.9 per cent).

Table 4.4 Electoral competition (uncertainty) and firms’ strategies (capture) in local elections in Benin

| Mean treatment | Mean control | Diff. | Diff. SE | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demand policies | 0.466 | 0.489 | −0.023 | 0.04 | 0.575 |

| Procurement | 0.714 | 0.605 | 0.109 | 0.038 | 0.004 |

| Patronage (from and not from firm) | 0.386 | 0.37 | 0.016 | 0.039 | 0.68 |

| Patronage (from firm) | 0.392 | 0.379 | 0.013 | 0.039 | 0.742 |

| Support candidate (future) | 0.161 | 0.177 | −0.016 | 0.03 | 0.593 |

| Change in policy programme | 0.087 | 0.164 | −0.077 | 0.026 | 0.004 |

| Refund | 0.042 | 0.071 | −0.029 | 0.018 | 0.118 |

| Bureaucracy recruitment control | 0.177 | 0.167 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.75 |

| Demand budget line | 0.064 | 0.058 | 0.006 | 0.019 | 0.738 |

| Firm capture index | 4.45 | 4.318 | 0.132 | 0.117 | 0.258 |

| Firm capture index (standardised) | 0.045 | −0.046 | 0.091 | 0.081 | 0.258 |

We construct an index of firms’ state capture ranking strategies in the following order, from the weakest to the strongest form of state capture: refund=0; policy and programme change demands=1; support to firms’ candidates in the future=2; control over the budget line=3; public procurement demands=4; patronage=5; and, lastly, control of the bureaucratic recruitment process=6. While non-significant, the results show that under a hypothetical high-competition setting the firms’ capture index is higher than in low-competition ones.

Thus, in short, the higher the electoral uncertainty, the stronger and more enforceable are the forms of commitment businessmen prefer. Interestingly, in the absence of a good candidate to fund, respondents say that businessmen are more likely to run for elections themselves. In this respect, about 60 per cent of respondents say that businessmen’s involvement has become a phenomenon in recent years; most of them run directly for elections.

A good example of the change in frequencies in firms’ capture preferences is the relationship between the former Beninese President Boni Yayi and the current President Patrice Talon, the richest businessman in the country. According to a respondent very close to the former, the latter used to finance politicians’ electoral campaigns, from presidents to local mayors. After supporting both the 2006 and 2011 Yayi presidential campaigns, Talon negotiated the biggest public procurement in Benin’s history. Thereafter, Yayi decided to end the collaboration, presumably due to the power imbalance that the procurement granted Talon. What followed was a clash between both actors, leading to a highly uncertain political environment. As a result, Talon first financed the campaign of the national assembly president, the second personality after the president. However, it seems that, given his experience with President Yayi and given the highly uncertain competitive electoral environment, Talon decided to run for president himself. He won the election on 6 April 2016.

Table 4.5 introduces the estimates of equation (1); that is, the effect of electoral competition measured by winning margins on firms’ preference for direct capture for both municipal- and legislative-level elections. The first column shows that when the winning margin increases – that is, when electoral competition decreases by 1 standard deviation – firms decrease their preference for more direct forms of state capture by −0.1684 standard deviation, a result that is significant to the 1 per cent level. Contrast this to the placebo test shown in the second column: winning margins hold a positive and non-significant effect for MPs. As noted before, MPs do not have a say in national- or local-level bureaucracy and thus would have no effect on firms’ strategies to mitigate electoral uncertainty. In this regard, the right-hand panel of Figure 4.3 provides an example of the asymmetrical relationship between winning margins and firms’ capture index by election type, with a negative relationship for municipal-/commune-level elections and a positive one for legislative-level ones.

Table 4.5 Effect of electoral competition (winning margin) on firms’ preference for direct capture, beta coefficients

| Dependent variable: firm capture index | ||

|---|---|---|

| Municipal level | Legislative level | |

| Winning margin | −0.1684*** | 0.0535 |

| −0.0801 | −0.0736 | |

| Observations | 117 | 96 |

| R-squared | 0.48 | 0.37 |

| Controlsa | yes | yes |

| Commune FE | yes | yes |

Standard errors in parentheses are clustered at the commune level; significance level (***) 0.1%. Outcome measured in standardised terms. FE, fixed effects. aElectoral district-level covariates include GDP, inequality, and 2015 electoral measures, including winning margin, and Herfindhal–Hirschman Index of party vote share concentration; politician characteristics controls include indicator levels of education levels by politician.

Moving forward, Table 4.6 presents the estimates of equation (2); that is, the effect of the electoral reform that collapsed the party system into a two-party block competition, decreasing the electoral risk of firms’ strategic decision-making to capture government. Results are expressed in standardised beta coefficients. As seen in the last column, the effect of a decrease in electoral uncertainty decreases the firm capture index by −0.259 standard deviation, significant to the 1 per cent level. This result is robust to the inclusion of district and politician characteristics, and district fixed effects. If we dissect the index, we notice that demands characterised by high degrees of capture are decreasing, especially patronage for family members, friends (−0.4374), members of the firm (−0.4365), and bureaucratic recruitment control. Meanwhile, less direct forms of capture increase or have negligible and non-significant effects, including refunds, support for candidates in the future that are supported by the firm, or demands for public goods procurement. Note, for instance, that there is actually a positive effect on budget line demand. Policies and programme modifications are negative and significant, showing that in settings of low electoral risk firms also decrease the use of such demands towards politicians.

Table 4.6 Effect of electoral reform (uncertainty decrease) on firms’ strategic decision-making, beta coefficients

| Dependent variable | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Refund | Policies | Programme change | Support candidate | Budget line | |

| Electoral reform | 0 | −0.6481*** | −1.0992*** | 0 | 0.4829*** |

| (decrease uncertainty)a | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Observations | 117 | 117 | 117 | 117 | 117 |

| R-squared | 0.327 | 0.544 | 0.466 | 0.415 | 0.739 |

| Controlsb | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Commune FE | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Procurement | Patronage | Firm patronage | Recruitment control | Firm capture index | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electoral reform | 0 | −0.4374*** | −0.4365*** | −0.6061*** | −0.2595*** |

| (decrease uncertainty) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Observations | 117 | 117 | 117 | 117 | 117 |

| R-squared | 0.508 | 0.402 | 0.494 | 0.506 | 0.391 |

| Controlsb | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Commune FE | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

Standard errors in parentheses are clustered at the commune level; significance level *** 0.1%. Outcome measured in standardised terms. a Outcomes with 0 imply a very small number; we preferred not to introduce scientific numbers and left this as is. b Electoral district-level covariates include GDP, inequality, and 2015 electoral measures, including winning margin and Herfindhal–Hirschman Index of party vote share concentration; politician characteristic controls include indicator levels of education levels by politician.

We further test in Table 4.7 the effect of the decrease of electoral uncertainty due to the introduction of the electoral reform on the use of non-programmatic politics and other actions by politicians at the district and commune levels. We notice two important results. On the one hand, in a more certain setting, politicians increase the use of non-conditional transfers to voters by 0.7186 standard deviation, with the result significant to the 1 per cent level, and they decrease the use of other types of expenses, including pork-barrel and non-visible expenses, such as expenditure on water and sewage infrastructure. In other words, as backed substantively by the clientelism literature, under conditions of certainty politicians rely heavily on non-programmatic politics and use non-conditional transfers to attempt to increase citizen electoral support.

Table 4.7 Effect of electoral reform (uncertainty decrease) on use of non-programmatic politics and transfers to business interests, beta coefficients

| Dependent variable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-conditional transfers | Pork-barrel expenses | Pro-business transfers | Non-visible expenses | |

| Electoral reform | 0.7186*** | −0.7240*** | 0.4834*** | −0.1202*** |

| (decrease uncertainty)a | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Observations | 117 | 117 | 117 | 117 |

| R-squared | 0.399 | 0.446 | 0.422 | 0.509 |

| Controlsb | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Commune FE | yes | yes | yes | yes |

Standard errors in parentheses are clustered at the commune level; significance level *** 0.1%. Outcome measured in standardised terms. a Outcomes with 0 imply a very small number; we preferred not to introduce scientific numbers and left this as is. b Electoral district-level covariates include GDP, inequality, and 2015 electoral measures including winning margin and Herfindhal–Hirschman Index of party vote share concentration; politician characteristic controls include indicator levels of education levels by politician.

On the other hand, and most important for this chapter, politicians under situations of low electoral risk increase dramatically their transfers to firms, an increase of 0.4834 standard deviation, significant to the 1 per cent level. This result goes hand in hand with the previous results: as electoral certainty rises, firms underuse high demands of government capture, in part due to an increase in politicians’ transfers.

V Discussion and Conclusion

A wide literature has shown the pernicious effects of business interests in institutional and democratic development. However, there has been little study of the underlying mechanisms by which firms deter democracy, especially in the context of weak states. This chapter provides evidence on the relationship between business interests and clientelistic contracts, and by doing so brings together two seemingly unrelated literatures: interest groups and state capture and clientelism. By doing so it provides, for the case of Benin, concrete evidence on the demand set applied by firms to politicians in exchange for firms’ support for electoral campaigns. More importantly, we show that more than half of Benin’s politicians are politically affiliated with firms, and that such affiliation affects the underlying base structure within which clientelist contracts with citizens take place.

We provide evidence that firms’ strategic interactions with politicians change as electoral uncertainty changes. In particular, in the most striking result of this chapter, we show that as electoral uncertainty decreases firms rely less heavily on more direct forms of government capture, including patronage or the control of local bureaucratic recruitment processes. In positive terms, paradoxically, this implies that democratic consolidation, which thrives with electoral uncertainty, is undermined by business interests.

‘Campaign finance and state capture’ provides a new perspective on topics that are at the heart of the literature on the political economy of development. In particular, the study of democracies in the developing world tends to focus on issues of clientelism or political exchange – directly or indirectly providing private benefits for constituencies in exchange for electoral support. However, as this chapter points out convincingly, not only are different forms of political exchange targeted at voters, different forms of political exchange are also practised by firms, each with potentially different implications for economic development and democratic consolidation. One problem with the literature on clientelism is that it tends to focus on political exchange between voters and politicians, without regard for the strategies of firms. Arguably, not only does this miss an important part of the dynamic for understanding political exchange more broadly, it also understates the developmental impact of clientelism. In focusing on small-scale ‘retail’ strategies, such as vote buying or patronage, we may be missing the more important forms of ‘wholesale’ strategies, such as capture or cooptation – strategies that arguably have more distortionary effects on both economic development and democratic consolidation.

As a result, in addition to highlighting important dynamics in Benin with implications for political institutions and economic development, this chapter addresses a first-order question in the literature on clientelism. This work is exemplary in leveraging results from a specific country context in order to make broader theoretical arguments. It does so by contributing both a novel framework – bringing together the two literatures on clientelism at the voter and firm levels – and bringing new data from Benin to test it.

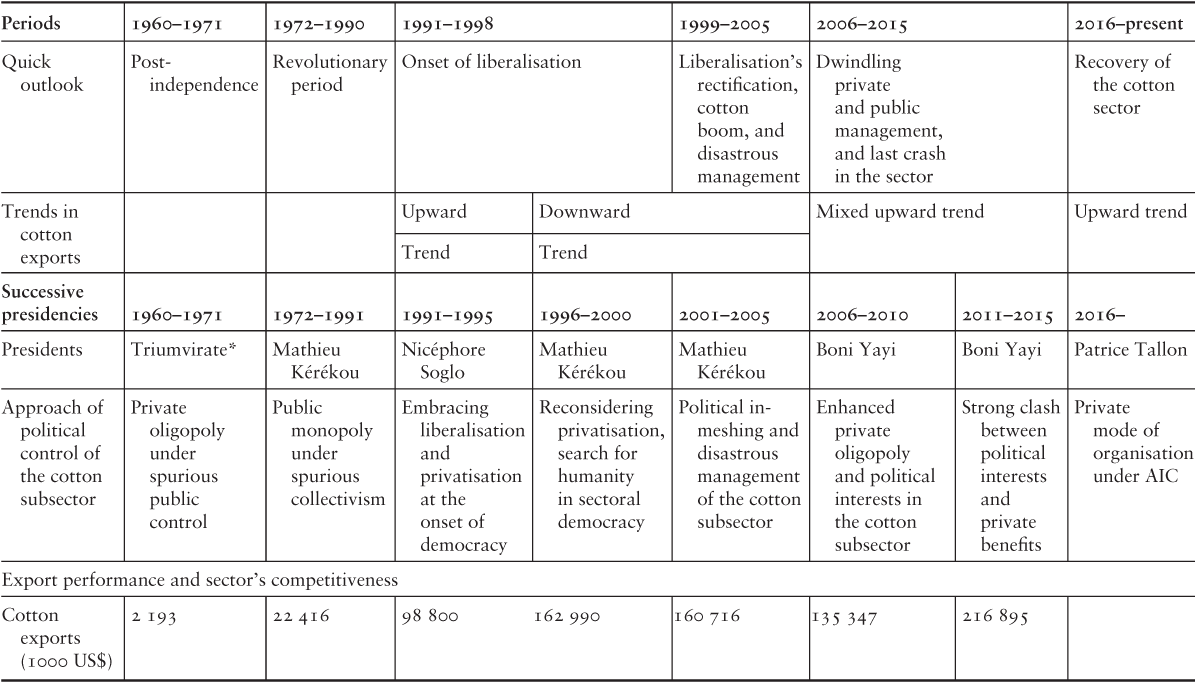

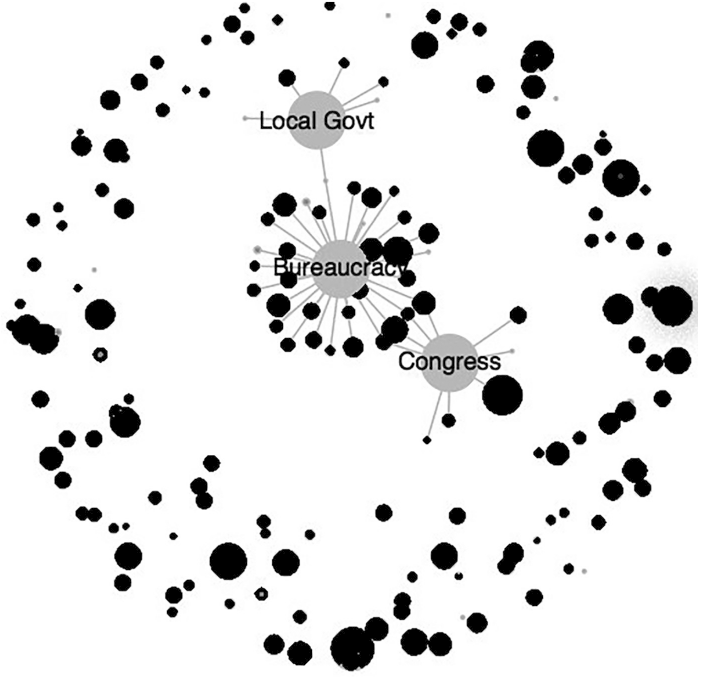

I Networks

One potentially helpful area for exploring extensions to this work is to think more about firm and politician networks. Theories of networks underlie both the literature on clientelism and the literature on firm capture and cronyism, making it a natural fit given that this project is bringing new data to create a unifying framework for the two literatures. Furthermore, networks are implicit in the chapter’s analysis (even if not sufficiently explicit) and, in fact, networks were a key part of the data collection because of the snowball sampling techniques.

Networks matter not only because of the direct connections, but also for understanding the broader structure of how business interests interact with clientelism. This short note addresses two types of networks, firm networks and politician networks, in order to suggest potential extensions to the analysis. Firm networks matter because they determine access to political ‘goods’, but also because the types of networks that firms invest in may provide evidence of their priorities and strategies for lobbying. As a result, firm networks would be expected to matter for the range of demands that firms might pursue, and their techniques for doing so. It is also possible that networks operate as a constraint on firm strategies – to the extent that firms invest in developing ties and cultivating relationships with a broad range of industry and government actors, it may be difficult for them to switch strategies even when political circumstances change (Fisman, Reference Fisman2001).