Introduction

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 15 August 2018

Summary

There you are, what a relief! I didn't know where to look for you. Did you think I wasn't ever coming back? I'll tell you what I went for. I was going to surprise you. I went to look for one of those books with maps in, what do you call them, so you could show me where you used to live. Atlases!

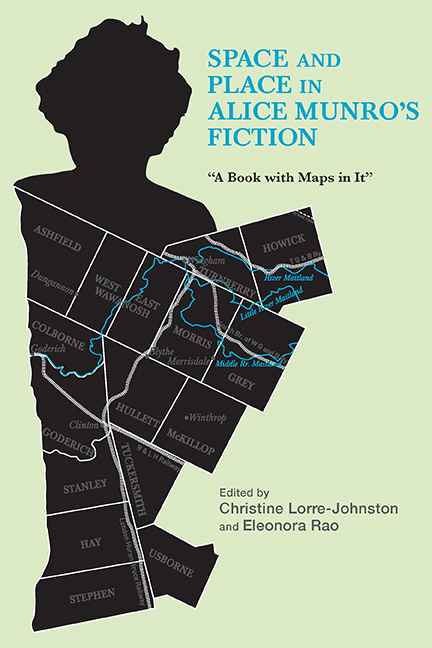

—Alice Munro, “Mrs. Cross and Mrs. Kidd,” The Moons of Jupiter (1982)IN ALICE MUNRO's “Mrs. Cross and Mrs. Kidd,” Mrs. Cross is a resident at Hilltop Home, where she is staying because of a bad heart, but the house gets all sorts of patients, because it “is the only place in the county, [and] everything gets dumped here” (MJ, 163). Mrs. Cross is looking for an atlas to communicate with her fellow resident, Jack, who has had a stroke and has lost his speech, hoping he will be able to point at the significant places of his life. She never finds an atlas, however, so Jack ends up communicating with her through one of the paint-by-number pictures on the wall, showing pine trees and three red deer, to signify the place he comes from, “Red Deer,” in Alberta. In the space of the “Home” that is not one, the “map” they re-create is made up of a combination of images and words that add up to a personal, improvised language of their own, and it constitutes the uncharted linguistic territory where they meet. This vignette, although it is set in the difficult environment of a rest home, demonstrates how our ability to improvise a personal language is a crucial aspect of our imagination and of our quest for place. The richness of Munro's narrative art may thus be likened to “a book with maps in it,” to use the phrase employed by Mrs. Cross when talking to Jack, which appears in the epigraph to this introduction: “I was going to surprise you. I went to look for one of those books with maps in, what do you call them, so you could show me where you used to live.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Space and Place in Alice Munro's Fiction“A Book with Maps in It”, pp. 1 - 24Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2018

- 1

- Cited by