This chapter will cover some of the key theoretical and practice issues associated with how social media have an impact on group and individual behaviour. The chapter will also address practical issues of relevance to professionals considering using social media as part of their efforts to promote mental health. In the opening section of the chapter, we set out an introduction to relevant behavioural theory and its implications for social media practice and how it can be used to promote positive engagement with social media.

The chapter will also examine how social media can be harnessed to promote mental health and provide guidance about the design and use of social media in the field of mental health promotion. The chapter will provide practitioners with understanding about how social media can have negative influence on both personal and group behaviour and how this can be minimized. The chapter will conclude with practical examples about how to utilize social media in mental health promotion and guidance that can be given to clients about how best to use social media as part of their own mental health promotion. The chapter will be illustrated with case studies and examples from a variety of countries.

Theoretical Foundations of How Social Media Influence Behaviour

The potential and actual impact of social media on well-being is explored in depth in other chapters of this book. Despite the ubiquitous nature of social media globally we are in fact still at the early stages of our understanding about their influence, limitations, and potential as a force for good or ill. As recent research has shown, there is no strong evidence that associations between adolescents’ digital technology engagement and mental health problems have increased in recent years [Reference Vuorre, Orben and Przybylski1]. We are however not starting from scratch as we have a great deal of theoretical understanding about how and why social media engender participation in their use and why so many people find them compelling and potentially addictive, helpful, and in some cases harmful [Reference Dahl2]. In this first section of this chapter, we will briefly explore some key theoretical perspectives that can help us understand both the role of social media in society and the basis of their potential to influence.

There are obviously multiple theoretical perspectives that have relevance to an understanding of social media and their impact on mental health and the other chapters in this book explore such theories. We are concerned in this chapter with the application of social media in the promotion of mental health, so we will briefly consider three theories that are focused on the nature of social influence, the mechanisms of social influence, and how these manifest themselves as functional elements of social media. Namely, we will explore the theoretical influence of Habermas’s theory of social spheres, Horton, Wohl’s parasocial interaction theory, Fogg’s functional triad of computer persuasion and Dahl’s 7s framework.

According to Jurgen Habermas, modern society depends on our ability to criticize and reason collectively about our own traditions. Technology, including social media, is one method of achieving this. Reason, according to Habermas [Reference Habermas3], sits at the heart of everyday communication and is driven by interrogating people’s actions through questions such as why did you do that? why do you think that? why did you say that? Habermas puts forward the view that reason is not about discovering truths but rather our need to justify ourselves to others. People undertake this reasoning in what Habermas calls the ‘public sphere’ which over time builds consensus, strengthens society, and ultimately brings about change. In this way society is developed through a process of active communication, sharing, and criticism. In term of the relevance to social media of Habermas’s theory of the consequences of the ‘public sphere’, many social media channels offer opportunities for such dialogue between individuals and opportunities for millions to both observe and participate in social dialogue. However, if social media platforms, like more traditional media such as newspapers and TV, are controlled and/or regulated by powerful state or commercial interests such opportunities can be diminished or stopped altogether. Social dialogue is then, if we accept Habermas’s view, essential to social development but it needs to be facilitated and exhibit critical reviews. This position obviously has implications for questions about monitoring, moderating, and restricting views or criticisms that are deemed by communities and social media providers to be inappropriate, offensive, and/or dangerous.

One of the key features of the social media communications sphere is that in theory everyone has an equal voice. In reality, however, some voices are louder and more pervasive than others. The impact of famous people’s voices on issues and as a way to endorse products, services, or ideas has been shown to not only boost awareness of issues but also have a measurable impact on the sale of products and services and increase the acceptance of ideas. This influence can be measured using tracking systems such as the Adly Influence Index (www.adly.com). One of the key features of social media and its impact is the role played by people perceived to be significant by groups of social media users. Parasocial interaction theory has useful explanatory power when considering this feature of social media. Parasocial interaction theory [Reference Horton and Wohl4] is focused on specific communication circumstances where communication is perceived by the recipient as immediate, personal, and also reciprocal but not by the sender.

People who follow a celebrity, for example on Twitter, develop a sense of a relationship and intimacy with them which can lead to even more influence. In reality, the relationship is one-sided with the celebrity having little or no personal awareness of the follower. It has been shown surprisingly however that social media-aided parasocial communication such as this can be perceived by followers as comparable with an actual social relationship and in that way can act as a powerful driver of both opinion and behaviour [Reference Lueck5]. In a world of increased social media engagement, understanding the persuasive potential of parasocial communication should be a priority for those seeking to influence positive mental health. A good example of how influences can be used is that of the 2020 TikTok campaign as part of mental health awareness month in the USA. TikTok videos were developed featuring influencers including Jaci Butler, Parker James, Sav Palacio, Hailey Sani, Sara Schauer, Enoch True, and Madison Vanderveen, promoting aspects of mental health awareness and resilience [6].

The final theoretical perspective we will cover in this opening section of the chapter is focused on two conceptual models that can help us understand how social media can be used as a practical tool to encourage and persuade people to adopt and sustain positive mental and physical health. The two models are Fogg’s (1999) [Reference Fogg7] functional triad model and Dahl’s 7s framework (2015) [Reference Dahl2] which together give a set of principles that can guide the design and development of persuasive social media strategy and applications.

Fogg identifies three dimensions of how technology can influence people. The three functional elements are:

1. to provide an experience;

2. to increase an ability; and

3. to create social relationships.

Fogg’s model has been used to design persuasion modes in a variety of contexts [Reference Torning and Oinas-Kukkonen8]. This tool is a helpful way for those interested in designing social media interventions to conceptualize what functions they will build into their social media applications and how they will position them as ways of increasing people’s abilities, providing engaging experiences, or helping them to build what they perceive as being meaningful relationships or a combination of these valued benefits.

Dahl’s 7S framework (2015) is a useful complementary set of features that can be perceived as sitting at the heart of Fogg’s triad model. Dahl has identified seven principles that should be considered when building social media and other forms of technology-based persuasive applications and services. These seven principles can be applied across a range of applications. The seven principles are:

1. simplification including ease of use and interaction;

2. sign-posting including links to other resources and support;

3. self-relevance including the ability to customize and control;

4. self-supervision including feedback on progress towards personal goals;

5. support including feedback and encouragement;

6. suggestion including problem-solving solutions; and

7. socialization including support for sharing success, and connecting with and helping others.

These seven principles can be used to guide the development of social media applications and as a checklist to evaluate the robustness of existing applications.

In summary, there are many theoretical perspectives that can help us understand how social media can influence personal and community beliefs, attitudes, and behaviours. The application of the theories already set out and those that appear in other chapters of this book can help identify the best ways to both understand what social media interventions might be needed and how to design them to enhance mental health.

The Range of Social Media Platforms and How They Impact Mental Health

As outlined in Dahl’s 7S framework (2015), the seven principles of social media applications have been applied in many well-established global social networking platforms including Facebook, Twitter, Snapchat, and Instagram, but also in newly formed and growing platforms including TikTok, Clubhouse, Parler, etc. Over time, the types of social media have not only diversified, but have increased the ease of access [Reference Sharma, John and Sahu9]. Outside of the typically considered social networking apps, there are many other platforms where people spend time online engaging in their interests and passions with like-minded communities. These include online gaming, online gambling, e-learning, and online coaching and counselling. These are massive networks all focused on enabling people to do something they enjoy and share their interests with others. These users are not just mindlessly browsing, they are constantly engaged, invested in what they’re doing, and often contributing to the community.

The list of positive mental health impacts of these social networks is considerable. For individuals who use social media as part of everyday routine, including responding to content that others share, such use has been positively associated with three health outcomes: social well-being, positive mental health, and self-rated health [Reference Bekalu, McCloud and Viswanath10]. Social media can also help individuals overcome barriers of distance and time and allow them to connect and reconnect with others to strengthen their in-person networks and interactions [Reference Bekalu, McCloud and Viswanath10]. Additionally, social media may increase social interaction or social connectedness, or act as a mechanism for meeting potential people who share the same interest, thoughts, and feelings and in so doing promote belongingness [Reference Andreassen, Pallesen and Griffiths11]. For youth, social media may also help to develop their identities and culture perspective [Reference Andreassen12].

However, a growing body of research has demonstrated that there are also negative impacts associated with social media use including an increased risk of depression and anxiety symptoms and a variety of other serious mental health impacts, many of which are explored in other chapters of this book. The way people are using social media has been found to have a greater impact on mental health and well-being than the frequency and duration of their use. Examples include behaviours such as checking apps excessively out of fear of missing out, or feeling disconnected from friends when not logged into social media [Reference Pantic13]. Excessive use of social media has also been found to be correlated with self-esteem, general and physical appearance anxiety, and body dissatisfaction [Reference Bekalu, McCloud and Viswanath10].

Cancel culture is also a new and growing complex and multifaceted problem. Such problems are often called wicked problems and require complex responses [Reference Churchman14] that have the potential to destroy people’s reputations, damage mental health, and create a negative online environment. There is no one definition of cancel culture, but Sarah Hagi, magazine writer and victim of cancel culture, defines it in her TIME magazine article as ‘[t]he idea … that if you do something that others deem problematic, you automatically lose all your currency. Your voice is silenced. You’re done’ [Reference Hagi15]. Cancel culture has however also been described by some as a form of online activism with both negative and positive effects. For the positive side, cancel culture has worked to emphasize the representation and voice of women during the #MeToo movement against sexual harassment, especially at workplaces. On the other hand, cancel culture has a reputation for being ‘activism-for-bad’ when it seeks to silence the voice of people that contribute challenging ideas to public debate around disputed issues.

How Practitioners Can Use Social Media to Promote Positive Mental Health

Social media platforms have become a high-priority channel for organizations to disseminate behaviour change communications. Platforms such as Instagram, Twitter, and YouTube are giving rise to a new phenomenon in which users treat their accounts like chat rooms for mental health, amassing tens of thousands of followers in the process. Influencers and brand owners alike have begun using their feeds to raise mental health awareness and even share their personal struggles.

Over the last few years, extensive growth in the e-counselling sector could be seen and has, despite various other ramifications, led to a need for information and guidelines for customers of such services. Due to these needs, in 1997 the International Society for Mental Health Online was founded, an international organization that aims to research the effectiveness of online mental health services and clarify licensing processes and therapy guidelines [16].

It is increasingly important for organizations to strategically decide on the right platforms suited to their target audience and behaviour change objectives. Similar to offline outreach tactics, it is not necessary to use every single platform. Including a variety of social media channels can increase participant involvement in a campaign, with the proviso that running a campaign well across the most appropriately suited social media channels makes more sense than trying to include networks that will not enable your target audience to take the action that your campaign is seeking. The box below outlines four key components necessary to consider before deciding to create a presence on a social media platform. It should be noted that these are necessary to review for each social media channel that is being considered.

When developing a social media presence on a platform it is important to consider the following components.

Character/persona – Who does your brand sound like? If you picture your social brand as a person, who is that character? Are they inspiring, friendly, professional, authoritative?

Tone – What is the general vibe of your brand? Scientific, clinical, honest, personal?

Language – What kind of words do you use in your social media conversations? Fun, jargon-filled, insider?

Purpose – Why are you on this social media channel in the first place? What is your social currency?

For most social media marketers, the burning questions are how best to reach out to social media users and what types of messages and tactics cut through the online clutter and engage the target group? A key way to formulate answers to these questions is reflected in social marketing practice which advocates a shift away from a focus of offering single motivational exchanges to the creation of sustained value [Reference Grönroos and Voima17].

The majority of social media users subscribe to a channel with the intention to follow and connect with family, friends, or like-minded people from which they derive continuous value. With the increasing presence of organizations and brands on social media platforms, users can also make a conscious choice whether or not to follow that brand or organization if they perceive it also provides them with some form of value. In terms of mental health promotion in social media, individuals ultimately decide if they are willing to engage with the campaign and, in order for them to want to do that, it must also provide a similar sustained value to them. Value also comes from participation: successful social media campaigns help users to feel like members of a community and establish identity by allowing participants to express part of themselves to others [18].

Case Study Example 1: The Holistic Psychologist – Using Instagram as a Movement for Mental Health #selfhealing

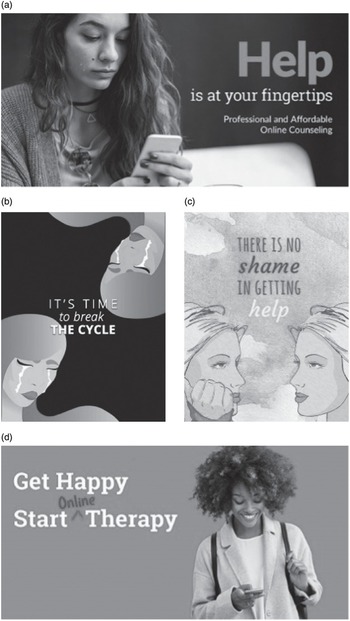

The Instagram account, @the.holistic.psychologist, was developed by founder Dr Nicole LePera (see Figure 4.1) who is a registered psychologist previously practising out of Philadelphia, PA. A typical Holistic Psychologist post has a few key elements: a colorful graphic with a small illustration or chart, accompanied by a caption, usually a couple of hundred words long, that elaborates on the central topic. Dr LePera’s posts ground her advice in her own experience as a mental health practitioner (see, e.g., Figure 4.2); however, her primary directive for her four million+ followers is learning to ‘self-heal’.

Figure 4.1 @the.holistic.psychologist’s first Instagram post making her intentions on the platform explicit from its inception

Figure 4.2 A post from @the.holistic.psychologist sharing the cycle of trauma responses, which received over 57,000 likes and 934 comments

Dr LePera’s teachings and the #selfhealers movement at large present an alternative for people who feel let down by traditional systems of mental health management. This could be due to inaccessibility or another alienating factors such as a lack of concrete results, sheer fatigue, or some combination of these obstacles. She also offers many other online free mental health management tools to use including an e-newsletter, and a YouTube channel where she posts a new video every Saturday.

As we have demonstrated in this chapter, social media is an umbrella term covering a varied field of applications and platforms. The social media ecosystem is also a dynamic field subject to constant change. Various forms of social media also appeal to different kinds of people at direct life stages. Some people use social media as a source of information and opinion formation, others use it as a source of news. Many others still use social media as a way of maintaining or expanding their social networks and building a wider circle of connection and influence. Others focus on using social media to share their life experience and interests. Some people are active content providers sharing personal news, opinions, and other news they feel is interesting and/or important.

Given this variety of usage when considering the use of social media in support of mental health promotion it is important that individual professionals, teams, organizations, and governments consider their objectives and how social media can be utilized to achieve them rather than starting from the default position that social media is important and should be used. Objectives come first; selecting social media as part of an execution mode should come second.

The following two sections set out how professionals and organizations can use social media as a part of their strategy for promoting mental health, and tips that can be given to clients and citizens about how to work with social media to protect and promote mental health.

Some Examples about How to Use Social Media to Promote Mental Health

Service promotions and help-seeking promotion

◦ for example, using service GPS location to help someone find the nearest clinic, support service, or mental health services – Google Maps

Building communities of interest/support

◦ for example, The Truth campaign leveraged TikTok to build interest – www.thetruth.com/activity/tik-tok-challenge-werk-it

Community building, facilitating ongoing connections with individuals and/or groups

◦ for example, AdvocatesForYouth uses TikTok around social advocacy issues: www.tiktok.com/@advocatesforyouth/video/6802276039780355334?lang=en&is_copy_url=1&is_from_webapp=v1

Providing online consultations, tele medicine, therapy, coaching, and counselling

◦ for example, Talkspace: www.talkspace.com/online-therapy/

Social and professional networking, and professional development

◦ for example, Mentorloop: https://mentorloop.com/

E-learning and team platforms (bite-sized education)

◦ for example, Udemy: www.udemy.com

Tracking population mental health concerns

◦ for example, WHO real-time tracking of people’s social media concerns: World Health Organization – EARS (Early AI-supported Response with Social Listening; Citibeats.com; Help Guide: Social Media and Mental Health: www.helpguide.org/articles/mental-health/social-media-and-mental-health.htm

Positive social norms promotion

◦ for example, Man Therapy in Australia: https://mantherapy.org/

Case Study Example 2: BetterHelp: The Pros and Cons of Using Online Influencers to Promote Mental Health Services

BetterHelp is an app which describes itself as ‘making professional counseling accessible, affordable, and convenient’ (see Figure 4.3). It provides customers direct access to behavioural health services online through the form of e-counselling. E-counselling, also known as e-therapy or online therapy, describes platforms that provide mental health services through the various means of online communication such as email, text messaging, video conferencing software, or online chats. BetterHelp was looking to build a strong online brand presence that would help it connect with its customers better. The company decided to create a series of online campaigns that would contribute to building BetterHelp’s brand identity. The challenge was to build an online presence for a multichannel platform in a sensitive industry that communicated the value proposition without any distortion.

A huge part of BetterHelp’s advertising strategy has been the use of influencer marketing. Its campaigns expanded over several social media platforms such as YouTube or Instagram, and it used intermediary platforms such as Popular Pays to recruit large amounts of influencers interested in participating in the campaigns. BetterHelp offered brand partnerships to some of the biggest influencers on social media, including YouTubers Shane Dawson and Philip DeFranco. The strategy is to have these influencers post very ‘personal videos’ about their struggles with mental health and encouraging their followers to seek help. They then promote the BetterHelp services and affiliate links which reportedly earn them money for every subscription contracted by one of their fans. While this has been an extremely successful strategy for the widely advertised online counseling app, some users reported that they felt the app was less reliable than it was promoted as being. It also shed light on the role of influencers who used affiliate links to the BetterHelp app which could be seen as capitalizing on their followers’ mental health as they earned a commission for every subscription to the therapy services.

Social Media Engagement and Measurement

Organizations that find the most success in their social media communities are those that can develop highly relevant content. Examples of high-value social media content are those that provide the following:

tips and tricks (life hacks), for example top 10 ways to reduce anxiety;

practical and easy applications to everyday life, for example 5-minute breathing exercises;

myth-busting factual information, for example triggers versus emotions;

inspiration, for example I can do that;

aspiration, for example I want to do that/I want to be like that; or

entertainment and evokes emotion.

Social Media Measurement

Using existing in-built social media tools, analytics and metrics can be easily captured to assess how successfully campaigns have engaged with participants and audiences. Typical social media analytics include the number of ‘views’, ‘shares’, ‘comments’, and ‘likes’ [Reference Freeman19]. However, it takes very little effort to like a campaign on Facebook, and there may be no direct link between the number of likes and the likelihood of behaviour change [Reference Freeman19]. Therefore, large numbers of followers or participants may actually mean very little in terms of how important or meaningful a campaign truly is [Reference Obar, Zube and Lampe20].

Deeper engagement would be considered as people sharing content as a form of advocating with the organization with the capacity to influence others. However, for academics and practitioners it is essential to establish if there is a connection between engagement and behaviour change. Measuring actual participation offline as a result of some exposure to a social media campaign should be a measurement objective such as making an appointment for counselling [Reference Freeman19]. Suggested methods for this include analysing the content of any online comments and interactions for evidence of behaviour change and conducting surveys and interviews with campaign participants to directly ask about their behaviour [Reference Freeman19].

Tips for Clients on How They Can Manage Their Use of Social Media to Promote and Sustain Mental Health

1. Set Limits to When, Where, and How You Use Social MediaFootnote 1

Excessive and compulsive use of social media can negatively impact on real face-to-face communication with family and friends. A good way to manage overuse of social media is to set certain times each day when your social media notifications are off or your phone is in airplane mode. Another good tactic to avoid overuse is to decide not to have access to or not to check social media during mealtimes with family and friends and when playing with children or talking with a partner. Not taking a mobile phone into the bedroom or switching it off after a certain time in the evening is also a good tactic. Excessive use of social media at work can add to pressure and interfere with work efficiency and performance. So, again, set limits to social media interaction while at work.

2. Share Your Story

Use social media to let others know about how you are managing your mental health. Share tips that you have found have worked for you and seek advice and support. Also try to focus your online interactions with people you also know offline. Talking about mental health is very important. It helps us to not internalize and recognize when we might need help.

3. Maximize the Benefits of Your Online Time

A few short spurts of focused uses of social media interaction can be less tiring and less stressful than spending a long time scrolling randomly through multiple feeds. Setting limits for interacting with different platforms can also be a good tactic to avoid this random scrolling. It is also a good tactic to try to be as active as possible when using social media. People who actively contribute rather than passively consuming others’ posts feel more positive and more in control.

4. Prune and Detox

Try to keep your social media life manageable. Over time, you have likely accumulated many online friends and contacts, as well as people and organizations you follow. Some content is still interesting to you, but a lot of it probably is not. Try to regularly prune your contacts, making your life more manageable. It’s a good idea also to schedule regular multiday breaks from social media. Studies have shown that breaks from using Facebook can lead to lower stress and higher life satisfaction. It may be difficult at first to prune and disengage from social media so seek help from family and friends by publicly declaring you are on a break or that you have certain times when you are positively offline.

5. Prioritize Your Real Life

Using social media to keep abreast of your cousin’s life is fine, as long as you don’t neglect to visit or talk in person. Tweeting with a colleague can be engaging and fun, but make sure those interactions don’t become a substitute for talking face to face or via a live video platform. Social media are useful additions to our social lives, but only a flesh-and-blood person sitting across from you can fulfil the basic human need for connection and belonging.

6. Be Supportive and Positive

It is important to remember that your choices and use of social media affect others. Do not spend your time online being cruel to people. Rather, spend time supporting your contacts. It is not your job to judge others online. Criticisms and negativity can significantly impact on others’ mental health. Use your social media profile wisely, be supportive and understanding – do not cyberbully.

Conclusion

This chapter has focused on some of the key theoretical and practice issues associated with how social media have an impact on group and individual behaviour. Social media platforms and campaigns have the potential to produce positive mental health benefits and well-being, but also have the potential to increase negative health outcomes.

For practitioners who are looking to implement mental health interventions and are considering using social media as part of their intervention mix, they first need to be very clear about who they are trying to help, what they know about them, and what their objectives are. To do this they will need to either undertake research or draw on previously published research and data before beginning any intervention design or implementation.

Subsequent to: strategic decisions about objectives; target group consideration of the right social media platforms to use; the development of content that can add value to people dealing with mental health issues or seeking to promote their mental health, an intervention can be developed and pilot tested.

Currently there is a lack of high-quality research and evaluation studies focused on the contribution of social media to the promotion and maintenance of mental health. There is then an imperative that practitioners and academics seek to capture the learning from interventions and make the learning and results available to others so that practice can be improved and mistakes avoided. A consideration of how social media fit with other aspects of mental health promotion and support services and interventions is also key as is the application of systematic social marketing planning procedures as they can assist substantially with this process [Reference French and Gordon21].