Introduction

At a time when social media and social media companies have played a complex, troubled role in recent political events, ranging from the 2016 US election and UK Brexit referendum to genocide in Myanmar, a growing chorus of scholars, policymakers, and commentators have begun proclaiming that social media – less than ten years ago cast as an emancipatory “liberation technology” – may now be fomenting polarization and undermining democracy around the globe (Reference Tucker, Theocharis, Roberts and BarberáTucker et al. 2017). As the executives of Google, Facebook, Twitter, and other major platform companies have been called to testify before elected officials in North America, Europe, and Asia, with policymakers discussing various regulatory measures to rein in the so-called digital giants (Reference Moore and TambiniMoore and Tambini 2018), the public is increasingly demanding greater accountability from the technology companies that operate the services entrusted with their sensitive data, personal communication, and attention. In the past several years, transparency has emerged as one of the leading accountability mechanisms through which platform companies have attempted to regain the trust of the public, politicians, and regulatory authorities. Ranging from Facebook’s efforts to partner with academics and create a reputable mechanism for third-party data access and independent research (Reference King and PersilyKing and Persily 2019) and the release of Facebook’s public-facing “Community Standards” (the rules that govern what the more than 2.2 billion monthly active users of Facebook are allowed to post on the site) to the expanded advertising disclosure tools being built for elections around the world (Reference Leerssen, Ausloos, Zarouali, Helberger and de VreeseLeerssen et al. 2019), transparency is playing a major role in current policy debates around free expression, social media, and democracy.

While transparency may seem intuitive as a high-level concept (often conceived narrowly as the disclosure of certain information that may not previously have been visible or publicly available; see Reference FlyverbomAlbu and Flyverbom 2016), critical scholarship has long noted that a major reason for the widespread popularity of transparency as a form of accountability in democratic governance is its flexibility and ambiguity. As the governance scholar Christopher Hood has argued, “much of the allure of transparency as a word and a doctrine may lie in its potential to appeal to those with very different, indeed contradictory, attitudes and worldviews” (Reference Hood, Hood and HealdHood 2006, p. 19). Transparency in practice is deeply political, contested, and oftentimes problematic (Reference EtzioniEtzioni 2010; Reference Ananny and CrawfordAnanny and Crawford 2018); and yet, it remains an important – albeit imperfect – tool that, in certain policy domains, has the potential to remedy unjust outcomes, increase the public accountability of powerful actors, and improve governance more generally (Reference Fung, Graham and WeilFung, Graham, and Weil 2007; Reference Hood and HealdHood and Heald 2006). As the authors of the Ranking Digital Rights Corporate Responsibility Index (an annual effort to quantify the transparency and openness of multiple major technology companies) argue, “[t]ransparency is essential in order for people to even know when users’ freedom of expression or privacy rights are violated either directly by – or indirectly through – companies’ platforms and services, let alone identify who should be held responsible” (Ranking Digital Rights 2018, pp. 4–5).

In recent years, a substantial literature has emerged in what might be called “digital transparency studies,” much of which critiques prevailing discourses of technologically implemented transparency as a panacea for the digital age (Reference Christensen and CheneyChristensen and Cheney 2014; Reference FlyverbomFlyverbom 2015; Reference FlyverbomHansen and Flyverbom 2015; Reference FlyverbomAlbu and Flyverbom 2016; Reference Stohl, Stohl and LeonardiStohl, Stohl, and Leonardi 2016). This work has been wide-reaching, touching on the politics of whistleblowing and leaking (Reference HoodHood 2011), the way that transparency can be politicized or weaponized to fulfill specific policy agendas (Reference Levy and JohnsLevy and Johns 2016), and the way that transparency has been enabled by technological developments and encryption (Reference HeemsbergenHeemsbergen 2016). Yet there has been less work that surveys the scholarship on transparency more broadly (drawing on organizational studies, political science, and governance studies, law, as well as digital media and political communication research; see Reference FlyverbomFlyverbom 2019) and applies it narrowly to the pressing questions around platform companies, social media, and democracy that are the focus of growing public and scholarly discussion, as well as this volume. The goal of this chapter is therefore to contextualize the recent examples of transparency as implemented by platform companies with an overview of the relevant literature on transparency in both theory and practice; consider the potential positive governance impacts of transparency as a form of accountability in the current political moment; and reflect on the shortfalls of transparency that should be considered by legislators, academics, and funders weighing the relative benefits of policy or research dealing with transparency in this area.

The chapter proceeds in three parts: We first provide a brief historical overview of transparency in democratic governance, tracing it from its origins in Enlightenment-era liberalism all the way to its widespread adoption in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. We quickly summarize what transparency seeks to achieve in theory and how it is commonly conceptualized as furthering traditional democratic values. In the second section, we provide a necessarily not comprehensive survey of major transparency initiatives as enacted by platform companies in the social media era, with a focus on the changes that firms have made following the 2016 US election. Finally, we discuss transparency in practice, with a summary of critical insights from the “digital turn” in transparency studies, which provides ample caution against transparency as a panacea for democratic accountability and good governance.

From Bentham to Blockchain: The Historical Evolution of the Transparency Ideal

Depending on how one precisely formulates what transparency is and what its key elements are, the origins of the concept can be traced back to various classical Chinese and Greek ideas about government and governance. Researchers have suggested that there are multiple, interrelated strains of pre–twentieth-century thinking that have substantially inspired the contemporary notions of transparency, including long-standing “notions of rule-governed administration, candid and open social communication, and ways of making organization and society ‘knowable’” (Reference Hood, Hood and HealdHood 2006, p. 5). However, it is generally accepted that transparency as it is understood today became popularized first in the writings of certain major Enlightenment political theorists, especially Jeremy Bentham, Immanuel Kant, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Their notions of transparency – often posited as an antonym to secrecy – reflected their presiding views about human nature, politics, and international relations. For Kant, arguing against government secrecy about treaties in his famous essay on “Perpetual Peace,” a lack of transparency could potentially worsen the effects of international anarchy and contribute to war (Reference O’Neill, Hood and HealdO’Neill 2006; Reference BenningtonBennington 2011). For Rousseau, transparency was primarily a way to increase the visibility of public servants, making it more difficult for them to defraud the state; he called for measures that would make it impossible for government officials to “move about incognito, so that the marks of a man’s rank or position shall accompany him wherever he goes” (Rousseau 1985: p. 72 cited in Reference Hood, Hood and HealdHood 2006). Bentham’s even more extreme ideals about publicity and visibility, as best exemplified by his infamous “panopticon,” seem to have been fundamentally rooted in pessimistic expectations about human fallibility and the corrupting influence of power (Reference Gaonkar and McCarthyGaonkar and McCarthy 1994). Bentham is often identified as the forefather of modern transparency as used in the political sense (Reference Hood, Hood and HealdHood 2006; Reference Baume, Alloa and ThomäBaume 2018). He famously wrote that “the more strictly we are watched, the better we behave,” an edict that inspired his approach to open government, arguing that “[s]ecrecy, being an instrument of conspiracy, ought never to be the system of a regular government” (Reference Hood, Hood and HealdHood 2006, p. 9).

Even before Bentham’s writings, however, one of the first apparent initiatives for government transparency in practice was underway in Sweden: the “Ordinance on Freedom of Writing and of the Press” (1766), proposed by the clergyman and parliamentarian Anders Chydenius (Reference BirchallBirchall 2011; Reference LambleLamble 2002), which provided citizens with statutory access to certain government documents. Chydenius, apparently inspired by the Chinese “scholar officials” of the Tang Dynasty “Imperial Censurate,” who investigated government decisions and corrupt officials (Reference LambleLamble 2002, p. 3), helped enact what is widely seen to be the precursor to all modern Freedom of Information Access (FOI or FOIA) legislation. While a handful of detailed historical accounts of the adoption of transparency measures as enacted by governments in specific countries exist, such as in the Netherlands (Reference MeijerMeijer 2015), it is generally accepted that modern political transparency emerged in the United States centuries after it did in Scandinavia (Reference Hood and HealdHood and Heald 2006). In the early and mid-twentieth century, a number of major American political figures, ranging from Woodrow Wilson and Louis Brandeis to Harry Truman and Lyndon Johnson, began publicly arguing that transparency was a moral good and an essential requirement for a healthy, democratic society (Reference Hood and HealdHood and Heald 2006). Wilson, channeling ideas expressed by Kant more than a century earlier, blamed secret treaties for contributing to the outbreak of World War I and made diplomatic transparency a significant feature of his famous “14 points” (Reference Hood, Hood and HealdHood 2006). Brandeis, a Supreme Court justice and influential political commentator, advocated for even broader forms of transparency in public affairs, famously claiming that “[s]unlight is said to be the best of disinfectants” (Reference BrandeisBrandeis 1913, p. 10). Brandeis’s ideas would culminate decades later in what the historian Michael Schudson has called the “transparency imperative,” as cultural changes and technological advances resulted in transparency becoming increasingly institutionalized in the United States across a multitude of public and private domains (Reference SchudsonSchudson 2015, p. 12).

The move toward today’s much wider embrace of transparency as a facet of contemporary democratic governance in the United States began with Truman, who signed the first of a series of important administrative orders, the 1946 Administrative Procedures Act, followed notably by the 1966 Freedom of Information Act and the 1976 Government in the Sunshine Act (Reference FungFung 2013). The 1966 legislation proved to be especially influential, with its main premise (a mechanism for citizens to request the public disclosure of certain government documents) effectively replicated by legislatures in more than ninety countries (Reference BanisarBanisar 2006). The goal of these initiatives was to reduce corruption, increase government efficiency by holding officials accountable, and generally promote the public legitimacy of government (Reference Grimmelikhuijsen, Porumbescu, Hong and ImGrimmelikhuijsen et al. 2013; Reference Cucciniello, Porumbescu and GrimmelikhuijsenCucciniello, Porumbescu, and Grimmelikhuijsen 2017). Through freedom of information requests – which have continued to expand in their scope since the 1960s, to the extent that “the right to know” has been postulated as a human right (see Reference SchudsonSchudson 2015) – as well as mandatory or voluntary disclosure programs, auditing regimes (Reference PowerPower 1997), and growing recognition of the importance of whistleblowing (Reference Garton AshGarton Ash 2016, p. 337), the concept of transparency became central to twentieth-century forms of power, visibility, and knowledge (Reference FlyverbomFlyverbom 2016).

Brandeis’s ideas continue to inspire transparency initiatives to this day, primarily among advocates of open government. Brandeis’s famous quote even provided the name for the Sunlight Foundation, a nongovernmental organization that advocates for government transparency on campaign finance, and groups such as Transparency International strive to provide access to information that can combat corruption, potentially unethical behavior, and better document how power is exerted in a democratic society. Less widely cited, however, is Brandeis’s full quote: “Sunlight is said to be the best of disinfectants; electric light the most efficient policeman. And publicity has already played an important part in the struggle against the Money Trust” (Reference BrandeisBrandeis 1913, p. 10). As Reference Kosack and FungKosack and Fung (2014) note, the initial target of Brandeis’s quest for transparency was not corrupt government but rather opaque corporations: the “Money Trust” of robber barons, bankers, and capitalists who were amassing great fortunes – and potentially defrauding the public – with little public accountability or oversight. In effect, Brandeis was anticipating impending corporate scandals, such as the 1929 Stock Market Crash, which led to an initial measure of corporate transparency and oversight via the formation of the US Securities and Exchange Commission, noting that the market itself provided limited information for consumers:

Then, as now, it was difficult for a grocery shopper to judge the ingredients contained in food products; this difficulty was compounded many times when an investor tried to assess the worth of more complicated products such as financial securities. Government, [Brandeis] thought, should step in to require companies such as food producers and banks to become fully transparent about their products and practices through laws and regulations.

In particular, Brandeis broke with the Enlightenment tradition of transparency as primarily a way to hold officials to account, also arguing that it could serve as a check against private power. By doing so, he set the intellectual foundations for the corporate transparency initiatives of the twentieth century.

Transparency and the Corporation

There has been a profound interest in transparency measures since their introduction in the United States in the 1960s (Reference SchudsonSchudson 2015), and, today, transparency measures are commonly proposed for a host of private and public actors. Archon Fung has written extensively about the fundamental democratic ideals of transparency underlying these efforts, which he argues are based on the first principle that “information should be available to citizens so that they can protect their vital interests” (Reference FungFung 2013, p. 185). Crucially, because “democratically important kinds of information may be information about the activities of private and civic organizations rather than governments themselves” (Reference FungFung 2013, p. 188), corporations that play outsize roles in public life should also ideally be as transparent as possible. Nevertheless, corporate transparency and accountability is generally only demanded once a corporation appears to threaten citizen interests – as in the case of the powerful banks that Brandeis was concerned about or in the archetypical case of the extractive natural resource companies or petrochemical companies (Reference FrynasFrynas 2005). As multiple labor and environmental scandals across different industries emerged, transparency became increasingly packaged as part of the “Corporate Social Responsibility” movement that emerged in the 1980s and 1990s (Reference RuggieRuggie 2013). For instance, anticorruption activists noted that good corporate behavior should go beyond just compliance with legal mechanisms but also involve active participation in various social responsibility initiatives and feature as much transparency as possible (Reference HessHess 2012).

Transparency was thus advocated as a core element of public accountability for business (Reference WaddockWaddock 2004) and enthusiastically announced as a way for firms to demonstrate their social responsibility and integrity (Reference Tapscott and TicollTapscott and Ticoll 2003). In practice, however, transparency has many important limitations. First, just like governments, corporations cannot be perfectly transparent, albeit for different reasons than governments – intellectual property is a central concern. Just as with governmental transparency, corporate transparency must achieve a compromise, which lifts “the veil of secrecy just enough to allow for some degree of democratic accountability” (Reference ThompsonThompson 1999, p. 182). Although transparency efforts are often backed by those who oppose regulation, governance scholars have argued that “transparency is merely a form of regulation by other means” (Reference EtzioniEtzioni 2010, p. 10) and that transparency alone can be no substitute for regulation. Indeed, meaningful transparency often needs to be backed with regulatory oversight, as scholars critical about corporate transparency in practice emphasize the possible existence of “opaque” forms of transparency that do not actively make the democratically relevant information visible but rather can be used to obfuscate processes and practices beneath a veneer of respectability (Reference Christensen and CheneyChristensen and Cheney 2014; Reference FlyverbomAlbu and Flyverbom 2016).

Overall, the track record of corporate transparency measures for promoting good governance has been mixed. Across multiple domains, from development projects to the private sector, it has been said that “actual evidence on transparency’s impacts on accountability is not as strong as one might expect” (Reference FoxFox 2007, p. 664). Corporate actors do not always play along and may only do the bare minimum without fully implementing voluntary or legislatively mandated transparency measures; as a comprehensive literature review of twenty-five years of transparency research notes, “the effects of transparency are much less pronounced than conventional wisdom suggests” (Reference Cucciniello, Porumbescu and GrimmelikhuijsenCucciniello, Porumbescu, and Grimmelikhuijsen 2017, p. 32). Empirical work into the results of transparency initiatives has shown its important limitations – for instance, a survey of mandatory disclosure programs for chemical spills in the United States suggested that the disclosures may have been up to four times lower than they should have (Reference FoxFox 2007, p. 665). Measures that run the gamut from audits, inspections, and industry-wide ombudspersons to parliamentary commissions and inquiries are often formulated as mechanisms of “horizontal transparency” that strive to let outsiders (e.g., regulators, the public) see inside the corporate black box (Reference FlyverbomHansen and Flyverbom 2015). However, the effects of these efforts can vary significantly, to the extent that “it remains unclear why some transparency initiatives manage to influence the behavior of powerful institutions, while others do not” (Reference FoxFox 2007, p. 665).

The pessimism about the possibility of successful transparency efforts in both the public and the private sectors has been somewhat counterbalanced in the past two decades by increasing optimism about the possibilities of “digital transparency” or “e-transparency” (Reference Bertot, Jaeger and GrimesBertot, Jaeger, and Grimes 2010). New information and communication technologies have promised to make transparency not only more effective but also more efficient by increasing the availability of relevant information (Reference Bonsón, Torres, Royo and FloresBonsón et al. 2012). Internet utopians like Wired magazine’s Kevin Kelly began arguing that the use of “digital technology in day-to-day life affords an inevitable and ultimate transparency” (Reference HeemsbergenHeemsbergen 2016, p. 140), and the collaborative, peer-produced “Web 2.0” seemed to provide multiple possibilities for blogs, wikis, online archives, and other tools through which interested stakeholders could access certain forms of democratically important information (Reference FlyverbomFlyverbom 2016). As some hoped that information and communication technologies could start laying the foundations for “a culture of transparency” in countries without a long-standing history of democratic governance (Reference Bertot, Jaeger and GrimesBertot, Jaeger, and Grimes 2010, p. 267), Reference HeemsbergenHeemsbergen (2016, p. 140) shows how others began proposing even more extreme forms of “radical transparency” via “networked digital methods of collecting, processing, and disclosing information” as a mechanism through which maximal social and economic growth could be achieved.

The latest technological innovations are constantly being harnessed for possible transparency initiatives – the recent spread of projects using distributed ledger systems (e.g., blockchain) to create open registries and databases provides perhaps the best example (Reference UnderwoodUnderwood 2016). Bentham would likely have approved of such initiatives; with a blockchain-based registry where each change is documented and permanently encoded in the database itself, theoretical levels of perfect transparency in a specific system can be achieved. From WikiLeaks to the encrypted whistleblowing platform SecureDrop, encryption has further helped digital transparency take root, with potentially significant impacts for the redistribution of power between states, citizens, and corporations (Reference HeemsbergenHeemsbergen 2016; Reference OwenOwen 2015).

In the past decade, a new generation of technology utopians has seized the ideological foundations set by the Enlightenment thinkers, positing “openness” as an organizing principle for contemporary social life. Facebook’s chief executive, Mark Zuckerberg, has preached for many years that his company’s products were creating “radical transparency” at a societal level, fostering more “open and honest communities” (Reference HeemsbergenHeemsbergen 2016, p. 140). Zuckerberg has publicly portrayed openness and transparency as key organizing features of the digital age while running a company that made increasingly important political decisions in secret (Reference GillespieGillespie 2018a). However, following the multiple scandals hounding Facebook since 2016, the mantra is slowly being turned inward: Zuckerberg has claimed that he will finally bring transparency to some of the company’s sensitive business dealings, most notably in the realm of political advertising (Reference FeldmanFeldman 2017). In public discourse, academics, policymakers, and civil society groups are increasingly advocating measures to look into the corporate black box of firms like Facebook and Google, positing it as a major potential governance mechanism that could rein in platform companies (Reference BrockBrock 2017). Yet how has transparency historically been enacted by these companies, and what are the recent measures that have been implemented in response to this public outcry?

Platform Companies and Transparency in Practice

A noteworthy feature of the twenty-first-century “platform society” (Reference Van Dijck, Poell and de WaalVan Dijck, Poell, and Waal 2018) is the relationship between, on one hand, the increasingly sophisticated sociopolitical and technical systems that now require transparency due to their political and democratic salience and the even more technical and complex sociopolitical mechanisms enacted to try and create that transparency on the other. For instance, large-scale algorithmic systems have been in the past few years roundly critiqued for their opacity (Reference BurrellBurrell 2016), leading to a growing movement for measures that produce “Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency” in machine-learning models and data-driven systems (Reference Barocas and SelbstBarocas and Selbst 2016; Reference HoffmannHoffmann 2019). As research in this area has shown, producing desirable forms of transparency while also preserving privacy and intellectual property in a computationally feasible manner is no easy task (Reference Edwards and VealeEdwards and Veale 2017; Reference Wachter, Mittelstadt and RussellWachter, Mittelstadt, and Russell 2018). Social media platforms present a similar challenge; companies like Facebook and Google have shown themselves to be highly important venues for political speech and deliberation around the world, and their increasing role as a global channel for news and political information means that they are now clearly institutions with significant democratic implications (Reference Garton AshGarton Ash 2016; Reference GorwaGorwa 2019a; Reference Van Dijck, Poell and de WaalVan Dijck, Poell, and Waal 2018). Their apparent influence, combined with many high-profile scandals, suggests that these firms can pose a threat to the average citizen’s best interests. Today, platform companies clearly meet the threshold articulated in traditional theories of democratic transparency for the types of actors that should require transparency, oversight, regulation, and accountability.

Platform companies, drawing from their ideological roots in historic countercultural and hacker movements (Reference TurnerTurner 2009), have come to embody a very distinct flavor of transparency. Internally, companies like Google and Facebook are famous for their founders’ embrace of “openness,” perhaps most clearly manifest in their physical workplace environments. At Facebook’s offices in Menlo Park, cubicles have been eschewed in favor of one of the world’s largest open-plan office spaces, meeting rooms have large glass windows or doors that allow employees to easily observe what goes on inside, and CEO Mark Zuckerberg works from the center of that open-plan office in a glass “fishbowl,” visible to all (Reference FlyverbomFlyverbom 2016). Google is known for its similarly designed offices and open office culture, including weekly Friday meetings where senior executives share information (oftentimes sensitive, nonpublic information) with effectively the entire company, engaging in an informal question-and-answer session where any employee can theoretically pose any question to higher-ups. In a 2009 blog post, a Google vice president explained that “openness” is the fundamental principle on which the company operates, ranging from their (admittedly self-serving) goal to make information “open” via their search engine and other products to their philosophy on open-source code, open protocols, and open corporate culture (Reference RosenbergRosenberg 2009).

While platforms have this notable internal culture of transparency, they are considerably less open to the outside world. To visit Facebook or Google as an outsider (perhaps a journalist, researcher, or academic), one must make it through the reception desk and keycard-entry turnstiles, usually after signing strict nondisclosure agreements. Externally, platforms are notable for their corporate secrecy – for example, it took twelve years for Facebook to release detailed information about its “Community Standards,” the rules that govern speech on the site, despite long-standing civil society and academic pressure (Reference GillespieGillespie 2018a). As the management and organization researcher Mikkel Flyverbom has written, platforms are characterized by “strong forms of vertical transparency, where employees and employers can observe each other very easily, but also as very little horizontal transparency because outsiders have very few opportunities to scrutinize the insides of these companies” (Reference FlyverbomFlyverbom 2015, p. 177). This has made research into platforms difficult, especially as firms shut down the developer APIs and other tools traditionally used by researchers to access data (Reference HoganHogan 2018). Much like a highly opaque bureaucracy, only a limited transparency has currently been achieved via public statements and interviews granted by their executives, as well as the occasional incident of whistleblowing and leaking. For instance, training documents issued to contractors that engage in commercial content moderation on Facebook were leaked to The Guardian, leading to significant public outcry and a better understanding of how Facebook’s moderation functions (Reference KlonickKlonick 2017). As we argue here, transparency initiatives for platforms can be classified into four camps: voluntary transparency around freedom of expression and for content takedowns; legally mandated transparency regimes; self-transparency around advertising and content moderation; and third-party tools, investigations, and audits.

Voluntary Transparency for Content Takedowns

Virtually since their emergence in the early 2000s, platform companies have had to weigh legal requests for content takedowns from individuals and governments around the world (Reference Goldsmith and WuGoldsmith and Wu 2006). As Daphne Keller and Paddy Leerssen explain in Chapter 10 in this volume, intermediary liability laws inform online intermediaries of their legal obligations for the information posted by their users, placing platform companies in the often uncomfortable position of having to weigh content against their own guidelines, local laws, and normative goals around freedom of expression. In an effort to maintain their legitimacy (and their normative position as promoters of free expression ideologically crafted in the First Amendment tradition), platform companies have become more transparent in the past decade about these processes as they pertain to content takedowns for copyright purposes and other legal reasons. To date, the dominant mode for horizontal transparency implemented by major platform companies has been in the area of these speech and content takedown requests.

In 2008, as part of an effort to combat censorship and protect human rights online, the Global Network Initiative (GNI) was created, with Microsoft, Yahoo, Google, and a number of civil society organizations and academic institutions as founding members (Reference Maclay, Deibert, Palfrey, Rohozinski and ZittrainMaclay 2010). As part of a commitment to the GNI principles, Google introduced an annual “Transparency Report” in 2010, the first company to publicly release data about content takedown and account information requests filed by governments around the world, along with a “Government Requests” tool, which visualized this data and provided a FAQ of sorts for individuals interested in the government takedown process (Reference DrummondDrummond 2010). Grandiosely citing Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Google positioned itself as a defender of free expression and civil liberties violations as enacted by states (Reference DrummondDrummond 2010). In the years to follow, these tools were expanded: In 2011, Google made the raw data underpinning the report public and, in 2012, the company added copyright takedowns under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) and other intermediary liability laws to the report.Footnote 1 In July 2012, Twitter began publishing a biannual transparency repot, which now includes information about account information requests, content-removal requests, copyright takedown notices, and requests to check content against Twitter’s own terms of service.Footnote 2 In January 2013, as it joined the GNI, Facebook began publishing its own bimonthly transparency report, which includes numbers about requests for user data, broken down by country, and, in July 2013, numbers about how much content was restricted based on local law.Footnote 3

In July 2013, documents provided to the press by Edward Snowden documented extensive governmental systems for mass surveillance, with the disclosures suggesting that the US National Security Agency (NSA) had access to unencrypted information flowing between Google data centers (Reference Gellman and SoltaniGellman and Soltani 2013). Google disputed the extent that information was collected via PRISM and other disclosed NSA programs but expanded its transparency reporting efforts to include information about National Security Letters and Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) court orders.

Voluntary Transparency for Content and Advertisements

The significant public pressure on platform companies following the 2016 US election has led to a new series of voluntary horizontal transparency initiatives that go beyond just content takedown requests. The most notable development has been the release of an expanded, public-facing version of Facebook’s “Community Standards” in April 2018. While Facebook transparency reports have since 2013 provided aggregate numbers about content that “is reported to [Facebook] as violating local law, but doesn’t go against Community Standards,” the details of those Community Standards were not public.Footnote 4 For instance, the Standards stated that content that featured sexual content, graphic violence, or hate speech was prohibited but did not define any of those highly contentious categories or provide information into how they had been defined, leading civil society and academics to almost universally critique Facebook’s processes as highly opaque and problematic (Reference Myers WestMyers West 2018).

Facebook’s publication of more detailed “Community Standards” that have information about the policies (e.g., how hate speech is defined, how sexual content and nudity is defined) gives far more context to users and marks an important step forward. Companies are starting to also provide detail about how these policies are enforced: At the end of April 2018, Google published their first “Community Guidelines Enforcement Report,” a type of transparency report that provides numbers into the amount of violating material taken down in various categories of the Community Standards and the role of automated systems in detecting content before it is reported (Google 2018). In May 2018, Facebook published a similar report, which illustrates different types of content takedowns, providing aggregate data into how much content is removed. For six parts of the Community Standards (graphic violence, adult nudity and sexual activity, terrorist content, hate speech, spam, and inauthentic accounts), Facebook provides four data points: how many Community Standards violations were found; the percentage of flagged content on which action is taken; the amount of violating content found and flagged by automated systems; and the speed at which the company’s moderation infrastructure acts in each case.Footnote 5

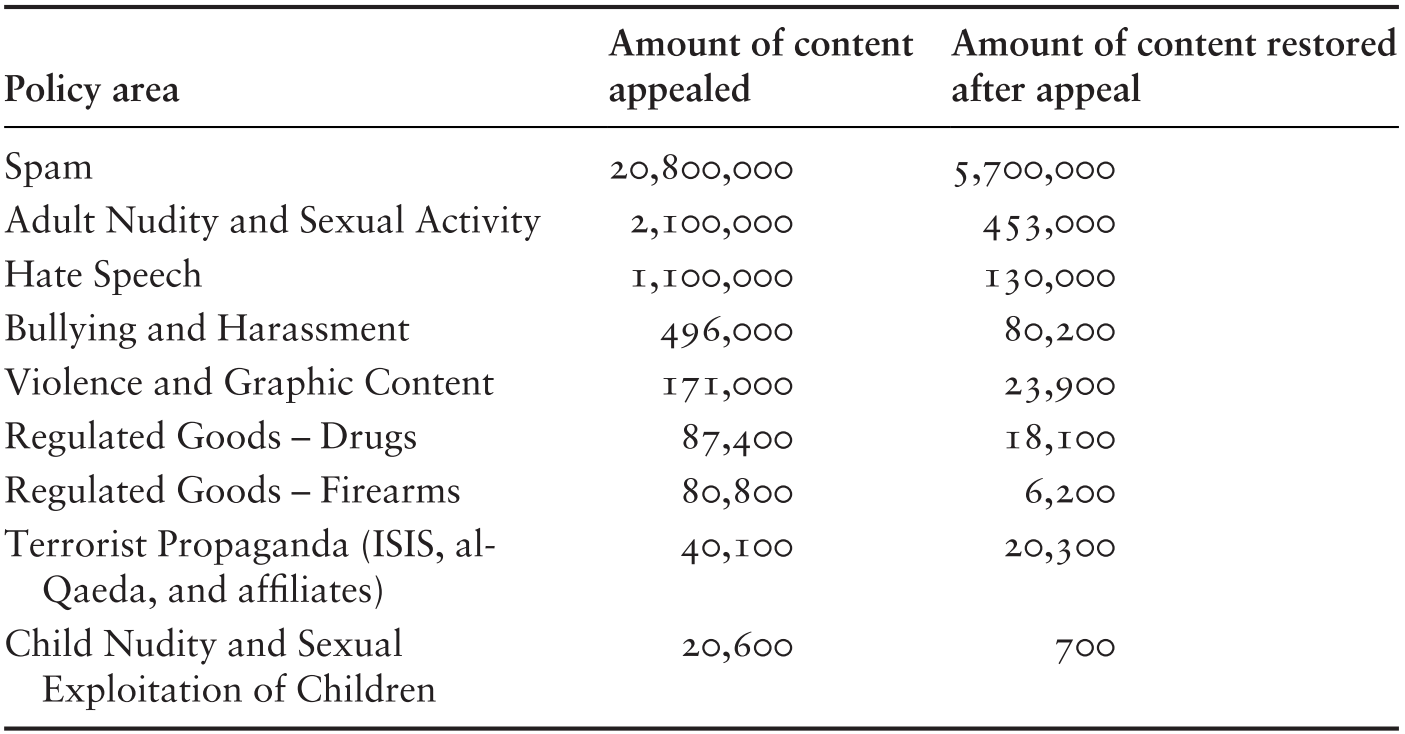

In May 2019, Facebook added multiple new categories to its Enforcement Report, including interesting data on the amount of content that is removed, appealed, and reinstated (since mid-2018, users who have content removed by Facebook’s manual or automated moderation systems can have those decisions appealed). For example, the report states that from January to March 2019, 19.4 million pieces of content were removed from Facebook under their policies prohibiting certain types of nudity and sexual content.Footnote 6 Out of that 19.4 million, 2.1 million (approximately 10.8 percent) was appealed by users, with Facebook reversing the decision in 453,000 (approximately 21.5 percent) of those instances (Table 12.1). Given the sheer quantity of Facebook content being posted by users every day, this may not seem like an enormous number; however, consider a hypothetical situation where each one of these appeals represents a separate user (setting aside for the moment that users could have had multiple pieces of content taken down): Before Facebook began allowing appeals in 2018, more than 400,000 people around the world could have been frustrated by the wrongful takedown of their images, videos, or writing, which may have had political or artistic merit (Reference GillespieGillespie 2018a) or may not have been nudity at all, picked up by a faulty automated detection system, for instance.

Table 12.1 Appeals data provided in Facebook’s May 2019 Community Standards Enforcement Report

| Policy area | Amount of content appealed | Amount of content restored after appeal |

|---|---|---|

| Spam | 20,800,000 | 5,700,000 |

| Adult Nudity and Sexual Activity | 2,100,000 | 453,000 |

| Hate Speech | 1,100,000 | 130,000 |

| Bullying and Harassment | 496,000 | 80,200 |

| Violence and Graphic Content | 171,000 | 23,900 |

| Regulated Goods – Drugs | 87,400 | 18,100 |

| Regulated Goods – Firearms | 80,800 | 6,200 |

| Terrorist Propaganda (ISIS, al-Qaeda, and affiliates) | 40,100 | 20,300 |

| Child Nudity and Sexual Exploitation of Children | 20,600 | 700 |

These reports are a major step and should continue to be expanded (Reference Garton Ash, Gorwa and MetaxaGarton Ash, Gorwa, and Metaxa 2019). Yet they still have notable limitations. As the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s Jillian York has written, the Facebook report “deals well with how the company deals with content that violates the rules, but fails to address how the company’s moderators and automated systems can get the rules wrong, taking down content that doesn’t actually violate the Community Standards” (Reference YorkYork 2018). The 2019 report focuses heavily on Facebook’s increasing use of automated systems to take down hate speech; as of March 2019, 65 percent of content Facebook removes under its hate speech policies globally is automatically flagged – up from 24 percent at the end of 2017. This is presented as an unqualified net positive, but the increasing use of automated systems in content moderation will have a number of underexplored consequences and promises to make content moderation more opaque (by adding a layer of algorithmic complexity) at a time when almost everyone is seeking greater transparency (Reference Gorwa, Binns and KatzenbachGorwa, Binns, and Katzenbach 2020).

In 2017 and 2018, Facebook also tested and rolled out a number of features with the stated aim to improve transparency around political advertising (especially in electoral periods). Following the discovery that Russian operatives had purchased Facebook advertisements to target American voters in the lead-up to the 2016 US election, Mark Zuckerberg issued an extended public statement in which he announced Facebook’s goal to “create a new standard for transparency in online political ads” (Reference ZuckerbergZuckerberg 2017). These efforts began in October 2017, when Facebook announced advertisers wishing to run election-related advertisements in the United States would have to register with Facebook and verify their identity and that these ads would be accompanied by a clickable “paid for by” disclosure (Reference GoldmanGoldman 2017). In April 2018, Facebook announced that this verification process would be expanded to all political “issue ads” (Reference Goldman and HimelGoldman and Himel 2018). Beginning in November 2017, a feature called “view ads” was tested in Canada, where users could navigate the dropdown menu on a page to see all of the ads that it was currently running (Reference GoldmanGoldman 2017). This was expanded to the United States and Brazil in the spring of 2018 and, in June 2018, allowed users to view ads run by a page across platforms (Facebook, Instagram, and Messenger). In May 2018, Facebook launched a public political ad archive of all political ads being run; and, in August 2018, Facebook provided a political ad API that would allow researchers and journalists to access this archive (see Reference LeathernLeathern 2018a, Reference Leathern2018b).

Other major platform companies simultaneously rolled out similar initiatives. In October 2017, Twitter announced a number of future advertising transparency efforts, including a “Transparency Center,” which launched in June 2018 and provided users with the ability to view ads targeted to them (along with the personalized information being used to target that ad, as well as a view of all ads being run on the platform) (Reference FalckFalck 2017, Reference Falck2018a). As well, Twitter has mandated that political “electioneering ads” are clearly distinct from other ads and has opted to provide information about the advertiser, the amount spent on the ad campaign, targeting data used, and other relevant information. These efforts remain a work in progress: In May 2018, Twitter announced their policy on political campaigning, to explain how they defined political advertising and the steps that political advertisers would have to take to register with the company; and, in August, they outlined their specific policy on issue ads (Reference FalckFalck 2018b). Google announced in May 2018 that it would require identification from any party seeking to run an election-related advertisement on a Google platform for a US audience and that all such ads would have a “paid for by” notice (Reference WalkerWalker 2018). In August 2018, Google added a “political advertising” section to its transparency reports, providing a public-facing tool for users to search for certain advertisers, a district-level breakdown of political ad spending in the United States, and a searchable ad database featuring all video, text, and image advertisements about “federal candidates or current elected federal officeholders.”Footnote 7

Mandated Transparency Regimes

Broader forms of transparency can also go beyond purely voluntary, self-regulatory processes and be mandated by either government regulation or by membership in certain organizations or institutions. Along with a commitment to public transparency via transparency reports, the GNI requires independent third-party assessments undertaken every two years to ensure compliance with the GNI principles (Reference Maclay, Deibert, Palfrey, Rohozinski and ZittrainMaclay 2010). These assessments are performed by a series of trusted auditors, who look into processes (the policies and procedures employed by the member companies) and review specific cases, with their findings compiled into a report released by the GNI (see, e.g., GNI 2016). Under the 2011 and 2012 Federal Trade Commission (FTC) consent decrees about Google and Facebook’s deceptive privacy practices, the two companies were required to subject themselves to privacy audits for twenty years (Reference HoofnagleHoofnagle 2016). As part of this regime, “compliance reports” are publicly available online at the FTC website, but the mandated third-party audits, which initially caused excitement as a possible transparency mechanism, are only published in heavily redacted and jargon-heavy form. These audits are thin on substance due to the watered-down language in the final FTC decree, making them, as one legal scholar argued, “so vague or duplicative as to be meaningless” (Reference GrayGray 2018, p. 4). The German Network Enforcement Act (NetzDG), which went into force at the beginning of 2018, seems to be the first piece of legislation in the world that mandates public transparency reporting for major platforms for user-generated content. All firms defined as operating social networks with more than 2 million users in Germany (Facebook, Google, Twitter, and Change.org; the law excludes peer-to-peer messaging services like WhatsApp or Telegram) must publish biannual reports that include details about operational procedures, content removals across various sections of the German Criminal Code, and the way in which users were notified about content takedowns (Reference Wagner, Rozgonyi, Sekwenz, Cobbe and SinghWagner et al. 2020). However, researchers have noted the limitations of the data made public in these transparency reports, which are not sufficiently granular to be empirically useful for secondary analysis (Reference HeldtHeldt 2019), and there have been differences in how companies have implemented their complaints mechanisms, eventually leading to a 2 million Euro fine levied by the German Federal Office of Justice against Facebook due to their insufficient transparency reporting (Reference Wagner, Rozgonyi, Sekwenz, Cobbe and SinghWagner et al. 2020).

In the past two years, a growing number of governments have pushed for platform companies to create publicly accessibly archives of political advertisements, with legislation relating to ad archiving being passed in France and Canada and being proposed and debated in the United Kingdom and the United States (Reference Leerssen, Ausloos, Zarouali, Helberger and de VreeseLeerssen et al. 2019; Reference McFaulMcFaul 2019). The European Commission’s Code of Practice on Disinformation includes a voluntary commitment from firms to develop systems for disclosing issue ads and recommends transparency without articulating specific mechanisms (Reference Kuczerawy, Terzis, Kloza, Kuzelewska and TrottierKuczerawy 2020). Ad archiving appears to be an important new frontier for transparency and disclosure, but major questions around the scope and implementation of its implementation remain (Reference Leerssen, Ausloos, Zarouali, Helberger and de VreeseLeerssen et al. 2019).

Third-Party “Audits” and Investigations

A final, indirect source of transparency and information about the dealings of platform companies is created by research and investigative work by third parties, such as academics and journalists. The investigative journalism nonprofit ProPublica has conducted multiple key investigations into Facebook’s advertising interfaces, successfully showing how, for example, those interfaces can be used to target anti-Semitic users or exclude certain minorities from seeing ads for housing or jobs (see Reference Angwin, Varner and TobinAngwin, Varner, and Tobin 2017a, Reference Angwin, Varner and Tobin2017b). This work also can rely on crowdsourcing. Before Facebook made their infrastructure for accessing advertisements through an Application Programming Interface (API) available, ProPublica built a browser extension that Facebook users could install to pull the ads that they saw on their Facebook, and a similar strategy was employed by the British group WhoTargetsMe, as well as researchers at the University of Wisconsin, who found that the majority of issue ads they studied in the lead-up to the 2016 US election did not originate from organizations registered with the Federal Election Commission (Reference Kim, Hsu and NeimanKim et al. 2018). Although Facebook itself seems to conceptualize third-party research as a meaningful accountability mechanism (see Reference HegemanHegeman 2018), it has not made it easy for this work to be undertaken, which generally violates platform terms of service and puts researchers on precarious legal footing (Reference FreelonFreelon 2018). It remains very difficult for researchers to conduct research on most platforms, with APIs having been constrained or totally discontinued by multiple companies in what some have termed an “APIcalypse” (Reference BrunsBruns 2019). Nevertheless, researchers and journalists have persisted in auditing and testing the systems deployed by companies, using public pressure and bad PR to mobilize incremental changes in, for example, how companies deploy their advertising tools (Sankin 2020). Since 2018, a few valiant efforts to try and provide institutionally structured and privacy-preserving data to researchers have emerged (Reference King and PersilyKing and Persily 2019) but have faced significant institutional, legal, and technical hurdles.

The Future of Platform Transparency

Facebook, Google, and Twitter have made efforts to bring more transparency to political advertising and content policy. These efforts certainly demonstrate a willingness to be more transparent about processes than a decade ago but, according to many civil society organizations, still do not go far enough. Efforts to measure the transparency measures of various companies discussed, such as an annual report conducted by the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), gave Facebook one out of five stars (citing a lack of meaningful notice to users who will have content taken down by a government or copyright request, as well as a lack of appeal on these decisions; see Reference Cardozo, Crocker, Gebhart, Lynch, Opsahl and YorkCardozo et al. 2018). Ranking Digital Rights, a project based at the New America Foundation, which produces an annual index with scorecards for 24 technology companies, internet service providers, and other online intermediaries, gave Facebook a score of 57 out of 100 in 2019. The researchers noted that Facebook “disclos[es] less about policies affecting freedom of expression and privacy than most of its US peers” and that the company “provided users with limited options to control what information the company collects, retains, and uses, including for targeted advertising, which appears to be on by default” (Ranking Digital Rights 2018, p. 87). Google ranked first out of the companies assessed (with a score of 63 of 100), with the report noting that they now allow users to opt out of targeted advertising and make more disclosures about freedom of expression, content takedowns, and privacy than other platforms but still lack robust grievance and appeal mechanisms (Ranking Digital Rights 2018, p. 89). The report’s 2019 iteration applauded Facebook for providing more transparency and user autonomy around free expression issues (e.g., by publishing its first Content Standards Enforcement Report and beginning appeals for content takedown decisions) but noted that it still lagged behind on privacy, offering “less choice for users to control the collection, retention, and use of their information than all of its peers other than Baidu and Mail.Ru” (Ranking Digital Rights 2019, p. 20).

Transparency is important for legislators and the public to have realistic expectations about what the processes and capabilities of platform companies to make decisions and take down content are. As Daphne Keller and Paddy Leerssen discuss in Chapter 10 in this volume, without transparency, policymakers misjudge what platforms can do and draft and support poorly tailored laws as a result. Yet the existing forms of horizontal transparency as currently enacted by these companies have major limitations. First, they are predominantly voluntary measures that have few enforcement mechanisms: The public must hope that the data provided is accurate but has little ability to verify that it is. A broader question can also be raised about the overall utility of transparency reports: While some features have clear democratic, normative importance, such as notice and appeals processes, the highly technical, aggregate statistics that are the core of most transparency reports are not necessarily useful in reducing the overall opacity of the system, where key processes, protocols, and procedures remain secret. Finally, a major limitation of the existing voluntary transparency measures, especially the advertising transparency efforts that have clearly been crafted to supplant possible regulatory regimes, is that these primarily public-facing tools may provide a rich and informative resource for students, researchers, and journalists but are notably less useful for regulators (e.g., electoral officers). Certainly, while Google’s new advertising library may be useful for students trying to understand attack ads, and may yield interesting tidbits worthy of investigation for reporters, meaningful ad archives – whether fully public or only offering more sensitive information to electoral officials and trusted parties – need to permanently archives advertisements, and display meaningful and granular information about spending and targeting (Mozilla 2019).

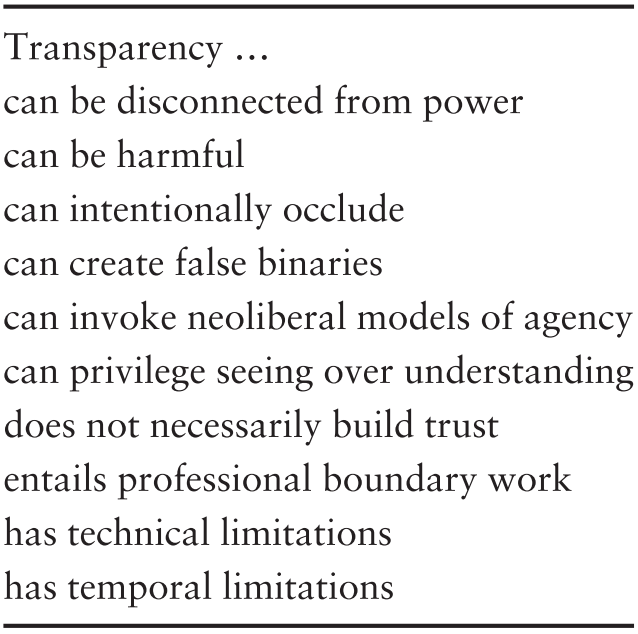

In an important article, Mike Ananny and Kate Crawford outline ten challenges facing transparency efforts that strive to govern complex sociotechnical systems, such as forms of algorithmic decision-making (Reference Ananny and CrawfordAnanny and Crawford 2018). The article is an important contribution to the recent literature on transparency as it pertains to technology policy issues and the digital age – a literature, one should note, that is roundly critical of the productive possibilities of transparency as a form of governing and knowing (Reference FlyverbomFlyverbom 2016).

Figure 12.1 Ten common digital transparency pitfalls

Many of Ananny and Crawford’s insights (Figure 12.1) can be applied to the case of platform transparency. For example, they warn that if “transparency has no meaningful effects, then the idea of transparency can lose its purpose” and effectively backfire, as it becomes disconnected from overarching power relationships (Reference Ananny and CrawfordAnanny and Crawford 2018, p. 979). If platform transparency efforts around advertising serve to make people cynical about the inevitability of poisonous attack ads or, on the other hand, ameliorate some narrow concerns about the generally problematic system of privacy-invasive advertising that funds contemporary platforms without actually making these systems more just, the efforts will fail to achieve a democratically desirable outcome (Reference TaylorTaylor 2017). Furthermore, certain forms of transparency can “intentionally occlude” (Reference Ananny and CrawfordAnanny and Crawford 2018, p. 980), burying the important insights in mounds of superfluous data or providing a distraction from the fundamental harms caused by a system. How useful are existing transparency reports, and do they distract from the end reality that some online intermediaries are making tremendously important decisions about the boundaries of acceptable political speech around the world in a fundamentally undemocratic and unaccountable manner? Do these measures provide the illusion of seeing inside a system, without providing meaningful understanding of how it really functions and operates (Reference Ananny and CrawfordAnanny and Crawford 2018, p. 982)? Do existing transparency measures lend a modicum of legitimacy and due process to a host of American private companies with global reach and impact, without actually providing good governance? These are crucial questions for scholars interested in the future of social media and its relationship with democracy.

The Search for Meaningful Transparency and Oversight

As governments grapple with a host of complex policy options, transparency mechanisms seem to provide a logical path forward. Platform companies seem willing to become more transparent and are even increasingly doing so voluntarily. When compared with broad and potentially messy legislation, transparency seems a fruitful, if limited, form of accountability that has the additional benefit of yielding information that better informs the future policy climate. Legislated transparency, which comes with third-party audits and verification measures, has the potential to improve the current status quo, and policymakers in Europe are moving to include some form of mandatory disclosures and perhaps even structured access to platform data for researchers as part of the Digital Services Act discussions that began with the onset of the von Der Leyen Commission. There is a great deal that firms could do to make the data they release as part of their transparency reporting more meaningful and reproducible. Possible changes range from adding specific data points, as outlined in the Santa Clara Principles for Transparency and Accountability in Content Moderation and other civil society efforts (who have long been asking for detailed figures on false positives, the source of content flags for different forms of content – government, automated detection systems, users, etc. – and many other areas), to taking a more holistic view of how they could conduct content policy in a more transparent and community-focused manner. A Yale Law School report commissioned by Facebook to provide recommendations into how it could improve its Community Standards reporting offers a number of positive ideas, including reporting certain major changes to policy ahead of time and going beyond today’s relatively ad hoc model of expert input to enact a more structured and public mechanism for stakeholder consultation (Reference Bradford, Grisel and MearesBradford et al. 2019).

One major initiative, slated to go into effect in 2020, is the “Oversight Body” for content policy that Facebook began developing in 2019. The proposal, which built on Mark Zuckerberg’s comments in 2018 about a “Supreme Court”–style mechanism for external appeals (Reference Garton Ash, Gorwa and MetaxaGarton Ash, Gorwa, and Metaxa 2019), seeks to formalize a system of third-party input into Facebook’s Community Standards. The initial conception of the Oversight Body focused primarily on procedural accountability, but, during a consultation process with academics and civil society groups, including the authors of this chapter, it appears to have become more broadly conceived as a mechanism “intended to provide a layer of additional transparency and fairness to Facebook’s current system” (Reference Darmé and MillerDarmé and Miller 2019). In September 2019, Facebook published a nine-page charter for the Oversight Board, which outlines how the board will be set up (via an independent trust), how members will be selected (Facebook will select an initial group, which will then select the remaining forty part-time “jurors”), and commits the company to acting on the board’s binding decisions.

Much yet remains to be seen about the board’s implementation and whether it truly results in a more democratically legitimate system of speech governance (Reference Kadri and KlonickKadri and Klonick 2019; Reference DouekDouek 2019) for the average Facebook user – someone who is far more likely to be a non-English speaker, mobile-first, and located in Bombay or Bangkok than Boston – or if it merely becomes a new type of informal governance arrangement, with more in common with the many certification, advisory, and oversight bodies established in the natural resource extraction or manufacturing industries (Reference 309GorwaGorwa 2019b). While a group of trusted third parties publishing in-depth policy discussions of the cases they explore, if adequately publicized and implemented in a transparent manner, certainly has the potential to increase the familiarity of social media users with the difficult politics of contemporary content moderation, it may not significantly increase the transparency of Facebook’s actual practices. The Oversight Board could even become a “transparency proxy” of sorts, attracting public attention while remaining little more than a translucent layer floating on top of a still highly opaque institution.

Conclusion

Transparency should help consumers and policymakers make informed choices. As the traditional argument for democratic transparency articulates, “People need information to assess whether such organizations protect their interests or predate upon them, to choose which organizations (and so which products and services) to rely upon, to decide whether to oppose or support various organizations, and to develop and execute strategies to affect and interact with them” (Reference FungFung 2013, p. 184). Yet the contemporary “attention economy” that characterizes most digital services is profoundly opaque, and users are intentionally kept from seeing much of how their behavior is shaped and monetized, whether by the multitude of hidden trackers and behavioral advertising pixels that follow them around the Web or by the secret rules and processes that determine the bounds of acceptable speech and action. As citizens weigh the trade-offs inherent in their usage of social media or other services provided by companies like Facebook, Google, or Twitter, they deserve to better understand how those systems function (Reference Suzor, West, Quodling and YorkSuzor et al. 2019).

The companies have displayed a commendable effort in the past decade to provide some data about the way they interact with governments when it comes to freedom of expression; however, these tend to offer more insight into government behavior rather than their own. Extracting the policies, practices, and systems through which platform companies affect free expression or other democratically essential areas such as privacy is an uphill battle, with journalists, academics, and activists painstakingly trying to obtain what they can, as if pulling teeth from an unwilling patient. Policymakers in Europe especially are starting to see the measures enacted willingly thus far by Facebook, Google, and Twitter as unlikely to result in meaningful long-term reform (Reference FrosioFrosio 2017).

Digital transparency – whether it is enacted through technological solutions or more classical administrative and organizational means – will not on its own provide an easy solution to the challenges posed by the growing role of platforms in political and public life. More research will be required to examine how platform companies enact and perform transparency and how this transparency functions in an increasingly contested governance landscape.

As Reference Ananny and CrawfordAnanny and Crawford (2018, p. 983) argue, “A system needs to be understood to be governed.” Transparency in key areas, such as content moderation, political advertising, and automated decision-making, should be an important first step reinforced by legislators. In the United States, the Brandeisian tradition of thinking about transparency in combating corporate power has often been neglected by the new cadre of advocates picking up the antitrust banner. While it is important to reflect critically on the pitfalls and shortcomings of transparency initiatives, a significant amount of robust transparency, legislatively mandated where necessary, would certainly contribute to the public understanding of the digital challenges facing democracies around the world.