The façade of the Palacio de Justicia in Bogotá, which is home to Colombia’s apex courts, reads: “Colombianos, las armas os han dado independencia. Las leyes os darán libertad” (“Colombians, guns have given you independence. Laws will give you freedom”). This quote is attributed to Francisco de Paula Santander, the famous Colombian military and political leader who was known as “the man of the laws.” Left unspecified by Santander was the nature of that freedom promised by law.

Colombia’s constitutional history indicates deep disagreements about the kinds of freedoms that can or ought to be enshrined in law. This chapter offers an overview of Colombian constitutionalism, focusing on the forces that led to the drafting of the 1991 Constitution. Following decades of social and political crises, Colombian social movement leaders demanded fundamental changes to the country and its legal system, though they did not rally around a particular constitutional vision. Instead, that vision came together piece by piece as the country’s most diverse constituent assembly met and debated the content of the new 1991 Constitution. Drawing on a wide range of sources, this constituent assembly ultimately proposed a constitution that would recognize not only civil and political rights, but also social, economic, cultural, and even environmental rights. What’s more, they also created a new legal procedure called the tutela that would allow Colombians to make claims to their newly codified rights.

The members of the constituent assembly did not imagine the scope of the changes to Colombian life that would come with the implementation of this new constitution. Prior moves in the direction of legally defined social commitments had never become embedded, as they were unable to endure changing political winds. How exactly social constitutionalism came to be embedded in Colombia is the subject of Chapters 3 and 4. In the rest of this chapter, however, I turn to the constitutional developments that preceded the adoption of social constitutionalism. I close with a description of the resulting constitutional text and general trends in the practice of legal claim-making in the context of social constitutionalism in Colombia.

3.1 Early Colombian Constitutional History

In 1821, delegates at the Congress of Cúcuta drafted Colombia’s first national constitution, following years of regional constitutional orders.Footnote 1 This constitution is alternately known as the Constitution of 1821, the Constitution of Cúcuta, or the Constitution of Gran Colombia. A commonly told story features the independence-fighter and then vice-president Francisco de Paula Santander opening this constitutional text and laying it out over a sword, stating: “The swords of the liberators must now be subject to the laws of the republic.”Footnote 2 This constitution marks the beginning of the intersection of national politics and constitutional law in Colombia.Footnote 3

From 1821 to 1886, the country had seven constitutions, each marking intermediate points in conflicts between conservative and liberal political actors, where the victorious side drafted a guiding document in an attempt to consolidate its power.Footnote 4 None of these constitutions survived for more than twenty-three years. The longest lasting of these, the 1863 Constitution, which was also known as the Constitution of Rionegro, was implemented by a Liberal government. The 1863 Constitution featured a sizable Bill of Rights for the time and introduced a federal governing arrangement. Víctor Hugo dismissed this constitution as being “a constitution fit for angels,” rather than one fit for Colombia (Cepeda Reference Cepeda2004: 532).Footnote 5

Following yet another internal armed conflict, which culminated in the Battle of Humareda, Rafael Núñez came to power. In that moment, he is said to have declared: “The Constitution of 1863 has died.”Footnote 6 A constituent assembly comprised primarily of Conservatives drafted a new constitution in 1886; one that affirmed the power of the Catholic Church, defined a centralized state, and rolled back many of the liberal reforms of the 1863 Constitution. The 1886 Constitution also set out a broader role for the judicial branch than outlined in previous constitutions. Namely, it bought about the possibility of judicial review in Colombia. In this system, the Supreme Court had the power to examine the constitutionality of legislative bills, though only under a limited set of circumstances.

A 1910 reform introduced the “public act of unconstitutionality,” which allowed citizens to challenge the constitutionality of any law before the Supreme Court (Cepeda Reference Cepeda2004: 538).Footnote 7 The reform in 1910 is just one of seventy-four reforms to the Constitution in its 105-year existence. These reforms – which created “practically a new constitution”Footnote 8 – began to “introduce a series of guarantees, particularly with the reform of 1936, which brought social rights into the Constitution … [including the idea of] the social function of property and the first land reform law in Colombia.”Footnote 9 The 1936 reforms, which included substantial changes in matters of agriculture, education, and taxes, and allowed the state to play a more active role in the economy, came at the initiative of Liberal President Alfonso López Pumarejo. Hernando Herrera traces the ideas behind these reform efforts to “the influence of the German [Weimar] Constitution and the Mexican Constitution of Querétaro [of 1917].”Footnote 10 Julieta Lemaitre also points to broader regional trends, arguing that the Liberal efforts “to push through modernizing constitutional reforms … [echo] the wider Latin American aspiration to modernity and development in the 1950s and 1960s. The 1936 reforms are part of social reforms all over the world, which include the New Deal.” In her view, “[t]hese [we]re Western trends, and not particularly Colombian.”Footnote 11

As Julio Ortiz, who served as a justice on the Supreme Court, described it, these reforms could be understood as a “restricted social constitutionalism.”Footnote 12 However, they were quickly undermined. For one, they did not impact judicial decisions.Footnote 13 In other words, these rights were not claimed in the legal sphere, and judges did not expand the scope of these rights through decisions. Judges, in fact, seemed to play the opposite role, leading Manuel José Cepeda to conclude that “it was a case of sterilization by judicial interpretation.”Footnote 14 In addition, conservative elites opposed to President López Pumarejo attempted to initiate a constituent assembly to remove the legal foundation for these reforms. While these elites were unsuccessful in their efforts to once again reform the constitution, they did manage to roll back the reforms in the legislature.Footnote 15 Further, Gustavo Gallón, the founder of the Colombian Commission of Jurists, argues that “not only did [the reform of 1936] not become a reality, but it also gave rise to a very strong reaction on the part of the landowning sectors and was later translated into the violence of the ’50s and the [violence] which we have lived until today.”Footnote 16 Thus, while the 1936 reforms can be thought of as “constitutional antecedents” to the 1991 Constitution, as Hernando Herrera put it,Footnote 17 these reforms never became embedded in either a legal or social sense.

Subsequent reforms in the 1950s recognized the right of women to vote (1954) and instituted a power-sharing agreement between the Conservative and Liberal parties called the National Front (1957). This power-sharing agreement was meant to stymie the continued expression of bipartisan violence, which had been a reoccurring feature of Colombian politics since the late nineteenth century. The 1957 reform also brought into effect a system of “co-option” on the Supreme Court, which meant that the Court would nominate new justices internally, as long as political balance was maintained between the two major parties (Cepeda Reference Cepeda2004: 540). Amendments in 1968 paved the way for a transition out of the National Front, in addition to modifying congressional rules on a variety of matters. The National Front came to an official end in 1974, when both the major parties ran competitive candidates for president.

3.2 Endemic Violence and Constitutional Crises

The inadequacies of Colombian state institutions became abundantly clear in the late 1970s and 1980s, as violence between the state, guerrilla groups, paramilitaries, and drug cartels continued, multiple attempted constitutional reforms flopped, and the country remained under an almost constant state of siege. Violence perpetrated by guerrilla groups endured, as did violence by the state and paramilitaries in the name of combating the guerrillas. This violence often took the form of human rights violations against ordinary citizens.Footnote 18 Throughout this period, the infamous Medellín drug cartel grew in strength and prominence, wreaking havoc across the country through car bombings and other violent tactics, oriented at both state and nonstate actors. The judiciary especially became the target of cartel violence, as a result of the possibility of extradition to the United States for drug-related offenses. This led to the creation of jueces sin rostro (“faceless judges”) in the early 1990s: an effort to hide the identity of judges such that they would be able to decide cases without being subject to threats and homicide attempts.

Further, in 1985, the M-19, an urban guerrilla group, stormed the Palacio de Justicia, home to the Supreme Court and the Council of State, taking the sitting Supreme Court justices as well as hundreds of others hostage. The standoff ended twenty-eight hours later, following what has been described as an “excessive and disproportionate” military raid.Footnote 19 In the end, more than a hundred people, including twelve Supreme Court justices, died, and about dozen guerrillas were disappeared. According to Julieta Lemaitre (Reference Lemaitre2009: 66), the violence at the Palacio de Justicia became “a symbol of the reality of the war and the impossibility of peace” to the general public. Solidifying this perception of the impossibility of peace was the near-continual state of siege, which expanded presidential powers but also indicated an inability of the government to respond to the challenges it faced. Mauricio García Villegas (Reference García Villegas, Santos and García Villegas2001) found that between 1970 and 1991, the Colombian government declared a state of siege more than 80 percent of the time, creating what he calls a “constitutional dictatorship.”Footnote 20

This violent context did not inspire faith in the ability of the state, including the judiciary, to respond effectively to citizen needs. Economic inequality and insecurity further exacerbated citizen mistrust in the state. As Donna Van Cott (Reference Van Cott2000: 49) notes, “economic dislocations made more apparent the extreme concentration of wealth, productive resources, and positions of authority in the hands of a small elite, and the extent to which this elite ruled in its own economic interest.” Efforts to address any of these concerns seemed futile.

Two Liberal presidents – Alfonso López Michelsen and Julio César Turbay Ayala – unsuccessfully attempted to initiate constitutional reforms in 1978 and 1981, respectively.Footnote 21 The Supreme Court blocked both reforms on procedural grounds. In the case of the López Michelsen reforms, the Court argued that constitutional reform fell within the duties of the Congress, and that Congress could not delegate these duties. With the Turbay reforms, which had received congressional approval, the Court pointed to other procedural problems. In 1987, the Supreme Court announced that future plebiscites would be prohibited. Plebiscites had in the past, for example in 1957, led to constitutional reforms. John Martz (Reference Martz1997: 248) notes that “by early 1988 the topic [of constitutional reform] was the single hottest political issue in the media.” That year, President Virgilio Barco proposed a plebiscite on the issue of plebiscites. In an interview, Fernando Cepeda, Minister of Justice under President Barco, described this proposal by referring to the saying, “en derecho, las cosas son rehacen como se hacen, [or] in matters of law, you un-make laws the way you make them.”Footnote 22 The plebiscite was blocked by Congress, and other efforts by the Barco government to advance constitutional reform were stymied yet again by the Supreme Court and the threat of cartel violence (Van Cott Reference Van Cott2000).

In addition, three presidential candidates were assassinated between 1989 and 1990, including a young, popular Liberal senator by the name of Luis Carlos Galán.Footnote 23 As Van Cott (Reference Van Cott2000: 53) states, Galán’s death “seemed to symbolize the deaths of hundreds of judges, politicians, journalists, and common citizens.” Inspired especially by Galán’s death, but also by the general climate of seemingly unending violence, students throughout the country protested, calling for constitutional reform. Alejandra Barrios, one of the leaders of the student movement recalls their motivation:

This series of events caused us to mobilize for the right to live, for the right to die of old age … What we saw was no future, there was no way out. Impossibilities of negotiation, impossibilities of institutional changes. When we created the student movement, we were looking for a social pact. We understood the constitution not as a charter of rights or a legal agreement, but, in truth, as a new social pact … It was not so much about the content of the constitution as the chance to say, “This country has to find another way besides war.”Footnote 24

In 1989, the students organized a silent march to the Plaza de Bolívar: the site of the Palacio de Justicia and a frequent culminating point for protest marches in Bogotá. The following year, the movement asked voters to fill out an additional, seventh ballot (séptima papeleta) in support of the creation of a constituent assembly. Though the Barco government supported such an effort, the possibility of an official plebiscite and constitutional reform had to pass through the Supreme Court, which had blocked several previous reform efforts. Surprisingly, the Court accepted the Barco government’s arguments that the séptima papeleta represented the will of the people and that the president’s state of siege powers allowed him to convoke a constitutional assembly, as the country was in crisis. Voters overwhelmingly approved the proposed assembly.Footnote 25 At this point, there seemed to be agreement that, in this time of crisis, some kind of legal change was in order. The type of change, however, was by no means predetermined.

3.3 The Asamblea Nacional Constituyente and the Social Constitution

On December 9, 1990, Colombian voters elected seventy members to the constituent assembly,Footnote 26 including twenty-five members of the Liberal Party, nineteen of the demobilized Marxist guerrilla group Movimiento 19 de Abril (Movement of April 19, or M-19), eleven from a newly formed political party called the Movimiento de Salvación Nacional (Movement for National Salvation, or MSN), nine from the Conservative Party, and two each from the Movimiento Unión Cristiana (the Christian Union Movement, an evangelical group), the Unión Patriótica (Patriotic Union, a leftist political party affiliated with demobilized members of the FARC as well as the Communist Party), and indigenous movements. Fernando Carrillo Flórez, one of the leaders of the student movement, was elected from the Liberal Party list. The government appointed four additional members, two from the demobilized Ejercito Popular de Liberación (Popular Liberation Army), one from the Partido Revolucionario de Trabajadores (Workers Revolutionary Party), and one from El Movimiento Armado Quintín Lame (The Armed Movement of Quintín Lame, a recently demobilized indigenous guerrilla group). Álvaro Gómez Hurtado of the MSN, Antonio Navarro Wolff of the M-19, and Horacio Serpa Uribe of the Liberal Party shared the presidency of the constituent assembly.Footnote 27 Juan Carlos Esguerra, a constituent from the MSN list, notes the importance of this (ideological) diversityFootnote 28 in the composition of the assembly: “The one main difference between [the 1991] Constitution and all the others before … is the fact that it was drafted a group of Colombians that were representing the entire republic, that were directly elected by the people, and they were a very small but comprehensive and full picture of Colombia.”Footnote 29 This was the group of people who would determine which legal changes would take place – at least on paper.

The constituents divided themselves into five commissions, with each member deciding which of the commissions to participate in. All proposals put forward by the commissions had to be approved during two plenary debates. David Landau (2014: 89) argues that members of the constituent assembly “view[ed] solutions to the grave problems that the country was facing in 1991 in terms of judges and law” in large part due to the historical involvement of the Supreme Court “in a broad range of political disputes.” Even within the context of this legal focus, the constituents had a wide range of viable options from which to choose as they drafted a new constitution. When we take a close look at the ideational considerations of the constituents, we see that the adoption of social constitutionalism was neither inevitable nor necessarily expected by the actors involved in the constitutional debates. The constituents evaluated many approaches to constitutional law, and, perhaps more importantly, they did not always anticipate the consequences of the choices they made as they drafted a new constitution.

Those who were involved in the Constitutional Assembly uniformly recollected a commitment to exploring different legal traditions that could be adapted to better fit the Colombian context. Manual José Cepeda describes the preparation that he and the other advisors to President Gaviria undertook before the constituent assembly in the following way:

[E]very Saturday morning we had a discussion on comparative constitutional law with the president. From 9:00 am to 12:00 or 1:00 pm, we discussed how different problems were approached in different countries, problems that were relevant for Colombia. And we didn’t look only at the text of the constitution but [also] at the decisions rendered by the respective courts.Footnote 30

Hernando Herrera, who worked as an assistant during the assembly, explains that the “primary function [of the assistants] was investigative, looking at comparative law and what happened in other countries,” especially with respect to “how certain institutions in Colombia could work better.”Footnote 31 In assessing the resulting constitution, Herrera estimates that, in terms of rights protections, “one could say that about 25 percent come from Germany, 15 percent from Mexico, another 15 percent from Spain, 10 percent from North America, and the rest from Colombia.” He further recalled that “a fundamental element was the jurisprudence of the high courts of the United States, Germany, Mexico, and Spain.”Footnote 32 Diana Fajardo, who also served as an assistant at the assembly and who later became a Constitutional Court justice, confirms this comparative approach within the assembly, and points specifically to the constitutions of Spain, France, and the United States as having inspired different parts of the resulting 1991 Colombian Constitution.Footnote 33

For many constituents, the goal of this comparative inquiry was to determine the best way to modernize Colombia’s constitution. Constituent Jaime Ortiz (Reference Ortiz1991), drawing on the French constitutional theorist Georges Burdeau, defined the modern constitution as the proper guide for the 1991 assembly:

The modern constitution draws the contours, not of the existing order, but of the future. They indicate the place of the individual, the family, [and] the intermediary groups, define the rules to govern economic activity, the role of limits of property, indicate to the state the activities to be undertake and the needs to be met. They specify the extent and nature of the help [a citizen] can expect from the society as well as [his or her] duties within it. This idea of the future society that the text lays out is nothing other than the “idea of right” that power must be dedicated to realizing.Footnote 34

In addition, constituents referenced international law, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, in their draft proposals.

The Spanish legal tradition was particularly influential. As Rodolfo Arango – who also served as an assistant during the Constitutional Assembly – put it, the “the German and Spanish Constitutional Courts were the motor of constitutional development in the post-war period … but Spanish law – due to language – was perhaps most influential [on Colombian law].”Footnote 35 Arango points specifically to Spanish author Eduardo García de Enterría as key in developing the ideas that constitutions could have normative form and immediate, direct application, rather than serving as programmatic guides.Footnote 36 Mario Cajas adds that “Manuel Aragón Reyes and other Spaniards had some influence on the constitution … [The constituents] were looking at the Spanish model of estado social de derecho, and, in fact, the definition [of estado social de derecho] is the same” in the constitutions of both countries.Footnote 37 Still others point to Manuel García Pelayo – a prominent Spanish jurist and expert in comparative constitutional law – in tracing the connection between German, Spanish, and Latin American legal thought.

One might imagine that pressure from below included concrete ideational directives for how to change the existing constitutional order. In fact, this was not the case. Citizens did not necessarily advance a specific ideology or legal agenda other than change from the existing constitutional foundation. Julieta Lemaitre (Reference Lemaitre2009: 74) holds that:

Colombian legalism, the inheritance of Santander (“el hombre de las leyes”), had been attacked and questioned by the right and the left since the middle of the twentieth century … For the right, this legalism signaled the inability to understand the urgency of the defense of life and property. For the left, liberal rights were an illusion; they were the masked face of oppression. As such, both positions despised the foundational legalism [of Colombia].

As a result, social groups across the political spectrum felt the need for legal reform. Several guerrilla groups, including the M-19 and El Movimiento Armado Quintín Lame, demobilized around this time and were granted the opportunity to participate in the constituent assembly directly as constituents. In addition to these political actors who sought changes to the existing legal infrastructure, students formed a student movement for constitutional reform. As Rodolfo Arango explains, “the student movement opened the door for constitutional change that had not been possible before.”Footnote 38 However, this pressure focused on the need for constitutional change toward equality, democracy, and peace without necessarily going into details.Footnote 39 It would be a stretch to relate this directly to social pressure for change and any specific model of government responsiveness.

Importantly, as Eduardo Cifuentes recalls, the constituent assembly took place in the context of several other constitution-drafting experiences in Latin America He explicitly references the Brazilian constitution of 1988:

[T]hese constitutions generally introduced a very broad charter of fundamental rights … and the new Latin American constitutions recognized of economic, social, cultural rights as well as collective rights, together with fundamental rights. This was not an innovation of the 1991 constituent assembly, but it follows the current trend that was then in fashion in Latin America.Footnote 40

This context provided a set of examples of other states in the region exploring social constitutionalism, in whole or in part. Still, the Colombian constituents often went further in terms of rights recognitions and the development of mechanisms or institutions meant to promote and protect rights than their neighbors. For instance, the 1993 Peruvian Constitution did not include the right to housing or shelter, and the 1988 Brazilian constitutional reform did not involve the creation of an entirely new court to hear rights claims (though it did include the creation of a new constitutional chamber within the existing Supreme Court).

While ideas related to social constitutionalism were being experimented with in neighboring countries, constituents still made choices about whether and how to implement these ideas in the Colombian context. Rather than expanding these ideas, they could just as easily have adopted more restrictive versions, such as expressly nonjusticiable social rights, a position that had been favored by many experts on human rights law. Some members of the constituent assembly, like Alberto Zalamea Costa, cautioned against overinclusiveness in listing rights. Zalamea argued that a “list of the thousand and one rights is not necessary, but [instead, we need] the enumeration of the essential ones plus the rights that, for certain reasons, have been more violated in Colombia.”Footnote 41 For Zalamea, the rights to life, equality before the law, free association, and the prohibition of torture were these key rights.

Further, Colombia had long been a holdout relative to the rest of Latin American legal development, most clearly in their late adoption of a mechanism similar to the amparo (a writ of protection for constitutional rights).Footnote 42 Mexico adopted the mechanism in 1857, and Guatemala (1879), El Salvador (1886), and Honduras (1894) followed suit soon after. In the early twentieth century, Nicaragua (1911), Brazil (mandado de securança, 1934), Panama (1941), and Costa Rica (1946) adopted similar mechanisms. Next came Venezuela (1961), Bolivia, Paraguay, Ecuador (1967), Peru (1976), and Chile (recurso de protección, 1976). Colombia adopted the acción de tutela a full fifteen years after Chile and 134 years after Mexico. In other words, it was by no means obvious, in historical perspective, that Colombia would adopt regionally or internationally trending ideas about constitutional law at any particular point in time.

One can easily imagine the constituent assembly instead embracing a new vision of liberal constitutionalism, revising the rules governing the Congress and its duties (which it did in part), and stopping there. Considering Colombia’s historically conservative political sphere, as well as the interests of still-powerful elite families, and the violence that ensued after the previous attempt at social reform in 1936, the drafting of a liberal constitution seems to have been highly plausible. While the 1991 constituent assembly was more representative than any previous constituent assembly in Colombia, more than 41 percent of delegates came from the Liberal and the Conservative parties, and more than 15 percent came from the MSN, whose delegates were, for the most part, political and legal elites themselves. The assembly did include many “nontraditional” members, including delegates from demobilized guerrilla groups, but traditional political elites still maintained a majority.

Instead of doubling down on liberal constitutionalism, however, the constituent assembly embraced a robust social rights discourse and empowered new institutions, like the Constitutional Court and the Defensoría del Pueblo (akin to an ombudsman’s office), to defend these rights. This choice to embrace a newer form of constitutionalism came about as a result of the belief among the liberal and progressive members of the constituent assembly in the value of reforming and modernizing. For instance, Helena Herrán de Montoya used the following slogan in her campaign to be elected to the assembly: “Vote for me. As a constituent, I am going to reform Colombian political customs, and I am going to give you the possibility of guaranteeing rights that will serve us all.”Footnote 43 She later reflected on her time at the assembly, stating that, “we began to study other constitutions, to look at other alternatives to see how Colombian customs could be modernized through a new Constitution … [We] were told that we had to modernize the country by introducing fundamental rights, human rights.”Footnote 44

Conservative constituents did not necessarily agree on the importance of “modernizing” the Constitution as such. However, only twenty constituents came from lists created by conservative groups, and not everyone on the Movimiento Salvación Nacional list was ideologically conservative. Juan Carlos Esguerra explained to me that:

Even though I have always been a member of the Liberal Party, I was approached by Álvaro Gómez, who was the leader of the Movimiento Salvación Nacional, and he himself was a very representative conservative in Colombia, but he said, “I want to organize a group of people who include different tendencies and different political representations,” and so he made a list in which we were [both] Liberals and Conservatives.Footnote 45

Thus, the group of constituents who sought to draft a more modern constitution, moving away from liberal constitutionalism, was sufficiently strong to outweigh those who favored relative stasis in terms of constitutional rights protections.

In May 1991, the First Commission – the one tasked with determining the list of rights that should be included in the Constitution – put forward a proposal that favored the broad inclusion of all generations of rights.Footnote 46 The proposal held:

There is no doubt that the fundamental axis of democracy lies in recognizing a set of guarantees for the citizens and people of Colombia that not only dignify the content of life, but also progressively favor the formulation of new freedoms … It has been understood that human rights form an inseparable whole, without divisions or fundamental differences between the different generations, into which they can be subdivided doctrinally.Footnote 47 …

In terms of rights and freedoms, our constitution cannot sacrifice the exact expression of the guaranteed rights for brevity, nor risk possible misunderstandings that could derive from imprecise definitions.Footnote 48

Hence, instead of a simple list of rights, such as the one in force [in the Constitution of 1886], a Charter of Rights, Duties, Guarantees and Freedoms is proposed, in which the citizen can know exactly the rights and freedoms guaranteed by the State and the legal order that expresses them, with the greatest possible precision.Footnote 49

Although it was Diego Uribe Vargas, from the Liberal Party list, who presented this proposal, members from all of the various parties to the assembly signed it, even Alberto Zalamea, who had previously expressed a preference for a more limited list of rights.Footnote 50 After discussing this proposal, and debating which rights should be “considered fundamental,” the constituents voted on the text of each right in June 1991.

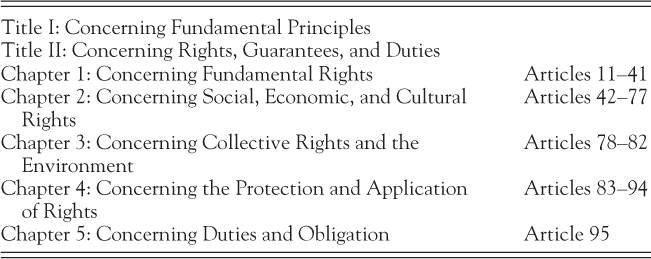

Ultimately, the assembly agreed to organize the list of rights into five chapters in a section of the Constitution titled “Concerning Rights, Guarantees, and Duties,” which would follow the section on fundamental principles. Social rights were not particularly divisive, receiving a high percentage of votes (e.g., fifty-eight of seventy for health, fifty-eight for housing, and fifty-two for education, compared to forty-three for the rights of children and forty-seven for the right to strike). And fifty-six constituents approved the text of Article 86, which describes the tutela procedure.Footnote 51 Table 3.1 shows each of the five chapters that articulate these rights, guarantees, and duties, as well as the articles that fall within each chapter. The Constitution was promulgated on July 4, 1991, and the newly created Constitutional Court began to hear cases the following year.

Table 3.1 Rights, guarantees, and duties in the 1991 Colombian Constitution

Title I: Concerning Fundamental Principles | |

|---|---|

Title II: Concerning Rights, Guarantees, and Duties | |

Chapter 1: Concerning Fundamental Rights | Articles 11–41 |

Chapter 2: Concerning Social, Economic, and Cultural Rights | Articles 42–77 |

Chapter 3: Concerning Collective Rights and the Environment | Articles 78–82 |

Chapter 4: Concerning the Protection and Application of Rights | Articles 83–94 |

Chapter 5: Concerning Duties and Obligation | Article 95 |

3.4 Claim-Making under Social Constitutionalism

Nothing about public discourse prior to the creation of the constituent assembly or the debates within it suggested any particular patterns in claim-making that would follow, except perhaps that claim-making related to civil and political rights should outpace claim-making related to social, economic, and cultural rights. The initial design of the tutela indicated that there would be an opportunity for claim-making for civil and political rights and not social rights. The idea underlying the tutela was that it would help to make the 1991 Constitution “real” to Colombian citizens and help to “give teeth to constitutional rights.”Footnote 52 Juan Carlos Esguerra uniquely proposed the acción de tutela instead of the more regionally common amparo procedure to protect the newly enshrined constitutional rights. Esguerra likens the tutela to the hero of the short story, radio, film, and television franchise Boston Blackie. Boston Blackie was considered a “friend to those who have no friend.” Esguerra recalls that “the tutela was intended to be the remedy for those rights who have no remedy at all, so that it would … complete a panorama of a law system that had lots of remedies.”Footnote 53 Article 86 of the Constitution outlines the tutela procedure:

Article 86. Every person has the right to file a writ of protection before a judge, at any time or place, through a preferential and summary proceeding, for himself/herself or by whomever acts in his/her name for the immediate protection of his/her fundamental constitutional rights when that person fears the latter may be violated by the action or omission of any public authority.

The protection will consist of all order issued by a judge enjoining others to act or refrain from acting. The order, which must be complied with immediately, may be challenged before a superior court judge, and in any case the latter may send it to the Constitutional Court for possible revision.

This action will be available only when the affected party does not dispose of another means of judicial defense, except when it is used as a temporary device to avoid irreversible harm. In no case can more than 10 days elapse between filing the writ of protection and its resolution.

The law will establish the cases in which the writ of protection may be filed against private individuals entrusted with providing a public service or whose conduct may affect seriously and directly the collective interest or in respect of whom the applicant may find himself/herself in a state of subordination or vulnerability.

The unexpected development with the tutela was its rapidly expanding scope. It was used not only for the civil and political rights that fall within the “fundamental rights” chapter of the 1991 Constitution, but also for social rights claims. Citizens pushed the bounds of the tutela, and judges endorsed this expansion. Between 2003 and 2019 (the period for which disaggregated data are available), the right to petitionFootnote 54 and the right to healthFootnote 55 were the most commonly invoked rights in tutela claims, as shown in Figure 3.1. In 2003, both types of claims were made around 50,000 times. Though health claims outpaced petition claims in 2008 (by about 30,000), after that year petition claims grew at a faster clip than health claims. In 2019, Colombians filed just shy of 245,000 petition claims and about 207,000 health claims. This story is not limited to claim-making regarding the right to health and the right to petition, however. Each year, Colombians file thousands of tutelas that invoke other rights, including, for example, the right to water (1,097 claims in 2019), the right to work (8,472 claims in 2019), and the right to due process (76,447 claims in 2019).

Figure 3.1 The most commonly invoked rights in tutela claims, 2003–2019.

According to reports by the Defensoría del Pueblo issued between 2012 and 2019, specific healthcare providers, the courts, and the Unidad para la Atención y Reparación Integral a las Víctimas (UARIV) – the national organization meant to oversee the implementation of the 2011 Victims’ Law (Law 1448), providing aid and assistance to those impacted by the internal armed conflict – have been subjected to the most tutelas each year out of all public and private entities. Claims against the courts have routinely amounted to about 5 percent of all tutelas filed each year during this period. Data from 2019 show that, in filing their claims against the courts, many Colombians held that their due process rights (76.9 percent), their right to access to justice (19.4 percent), or their right to petition (6.9 percent) had been violated.Footnote 56

In 2012, the first year of the UARIV’s existence, 7 percent of all tutelas (or nearly 30,000) were directed at that agency. This statistic increased to a high of 31.1 percent in 2016 and dropped consistently after that. In 2019, 10.6 percent of all tutelas named the UARIV. This number partially obscures the prevalence of victim-related tutela claims in Colombia’s biggest cities. In 2019, almost one-third of all tutelas directed at the UARIV in 2019 were filed in Medellín and almost one-quarter in Bogotá. Most of these claims (79 percent) formally invoked the right to petition, with the underlying goal being to attain the aid and reparation measures promised to those who are recognized as victims of the armed conflict.

Tutelas against healthcare providers primarily involve right to health claims (84.8 percent in 2019), as perhaps is obvious. Some of the time, however, the tutela claims invoked other rights, including the mínimo vital,Footnote 57 the right to petition, and the right to life. While some healthcare providers were the subject of just a few thousand claims, others were named in large percentages of all tutela claims. In 1999, the state-run social security agency, the Institute for Social Security, was the subject of 85.7 percent of all health claims and 16.1 percent of all tutela claims, statistics that fell steadily through the early 2000s. Nueva EPS (health) and Colpensiones (pensions) ultimately replaced the Institute for Social Security. Nueva EPS has been the subject of between 2.5 percent and 4.3 percent of all tutela claims each year since 2011. Colpensiones was named in 17.1 percent of all tutela claims in 2012, regardless of the right invoked. This percentage decreased through 2019, when Colpensiones was the subject of a mere 3.9 percent of all tutela claims. Over time, private healthcare entities came to be named in a substantial percentage of tutela claims as well.

What does this claim-making look like on the ground? As noted in Article 86, Colombians can bring tutela claims before any judge in the country (“at any time or place”). Their claims can be made orally or in writing. One judge explained to me that if you want to file a tutela, “you can go before a judge, sit next to him and tell him what happened, and the judge writes [out your claim] on the computer. That happens, it actually happens … I have seen them and I have processed verbal tutela claims. It does not happen in most cases but it does happen.”Footnote 58 More frequently, however, claimants stand in line outside courthouses, like the one shown in Figure 3.2, waiting to hand their typed or handwritten paperwork to a secretary whose primary job is to collect tutela claims. Judges then review these claims, assessing whether or not a rights violation may have occurred, regardless of whether or not the individual characterized the problem as one related to constitutional rights. This first instance of review must be completed within ten days. Further, ordinary courts are required to prioritize tutelas over other types of legal claims. As such, the tutela procedure offers individuals the chance to make claims without paying legal fees or enduring the time-intensive process of traditional litigation. Still, filing a tutela claim is not costless – individuals must travel to the courthouse during business hours and often wait in long lines to submit their paperwork. These time and resource costs pale in comparison to the costs of filing other kinds of legal claims, but they are not negligible for those of relatively little means.

Figure 3.2 People waiting in line to file tutela claims in Medellín, Colombia.

All tutelas are eventually sent to the Constitutional Court for possible review, though given the sheer quantity of tutela claims, the Court only formally reviews a small fraction of cases. At the Constitutional Court, the tutelas are first catalogued by law students from across the country, who serve as interns. During August 2016, Hernán Correa, who was then working as a clerk and law professor, but who was later selected to serve as a justice of the Court, gave me a tour of the courthouse and introduced me to the interns tasked with cataloguing tutela claims.Footnote 59 There were six interns assigned to each justice’s office, and these interns processed tutelas by the bag (see Figure 3.3). Atop each bag sat a Post-it labeled with a date and a number – the number refers to the whether the bag is the first, second, or fifteenth for that date (see Figure 3.4). That August, they received about 300 tutelas per day per office. With six interns working, that meant that each one had to read though fifty tutelas every day. The interns would type up the name of the claimant and the defendant, whether the claimant falls within a protected group, and a variety of other basic facts of the case. If the interns recommended the case for revision, they also included the lines of argument put forth by the first- and second-instance judge. One former intern described her time working at the Court to me as follows:

You work about a twelve-hour day, taking breaks to talk or mess around, of course, but the work is repetitive, especially in that so many of the cases had to do with health claims and prison conditions [This was in 2004.] Further, many of the lower-court judges simply copy and paste sections of other tutela decisions, even forgetting to change the name of the claimant. For this reason and others, bad decisions by the lower courts were quite common.Footnote 60

The Constitutional Court justices rotate who is on tutela duty for the week. The on-duty justice decides which of the claims flagged by their interns to formally review. Fidelity to existing jurisprudence and proper legal reasoning are understood to drive the revision process, but the decision about whether or not to review a tutela is ultimately subject to the discretion of the justices of the Constitutional Court, specifically whichever justices are on duty that week.

Figure 3.3 Interns cataloguing tutela claims at the Constitutional Court.

Figure 3.4 Catalogued tutela claims at the Constitutional Court.

3.5 Conclusion

This chapter documents the contours of Colombian constitutional history, up through the country’s adoption of social constitutionalism in 1991. The adoption of substantive social constitutionalism – with its recognition of not only civil and political rights but also social, economic, and cultural rights, alongside the creation of new legal institutions and procedures to give citizens opportunities to make claims to those rights – was not a foregone conclusion. Liberal constitutionalism remained a common constitutional model around the world, and some members of Colombia’s constituent assembly expressed a preference for that kind of model. The social constitutionalist view, favored by constituents who sought to “modernize” the Colombian state and Colombian constitutional law, won out.

The mere adoption of social constitutionalism did not guarantee that it would become embedded or institutionalized, especially considering that this adoption occurred at a time of profound social and political crisis. Examples of constitutional false starts and neutralization by political reactions or “sterilization by judicial interpretation” abound both globally and in Colombia’s past. What happened in Colombia, however, was that citizens began to routinely make claims to their constitutionally recognized rights using the newly created tutela procedure. The right to petition (a right that was initially categorized as “fundamental”) and the right to health (one that was not) came to be the most commonly invoked rights in tutela claims, even though, by design, the tutela was meant only to be used to claim fundamental rights. These claims are reviewed at the Constitutional Court, first by interns and eventually by the justices.

How exactly did this happen? Why did citizens embrace the tutela, using it to claim not just civil and political rights but also social, economic, and cultural rights? How did judges – both at the Constitutional Court and the lower courts – respond to these new rights claims? These are the subjects of the next two chapters. Chapter 4 tackles social embedding, while Chapter 5 looks to legal embedding.