A vision of law set out in a new constitutional text is not guaranteed to filter into either social or legal discourse. In fact, constitutions can be short-lived and subject to serial replacement (Levitsky and Murillo Reference Levitsky, Murillo, Brinks, Leiras and Mainwaring2013). According to Gabriel Negretto and Javier Couso (Reference Negretto and Couso2018: 7), the eighteen countries of Latin America collectively drafted 195 constitutions between 1810 and 2015.Footnote 1 To date, comparative scholars have focused primarily on the political dynamics that allow for different forms of constitutional change, specifically the emergence of judicial review and constitutional courts. Transitions featuring elite pacts help to explain the rise of both of these institutions, as actors facing the uncertainty of electoral politics are incentivized to create checks on power, assuming that another group may someday (re)gain power (Ginsburg Reference Ginsburg2003; Hirschl Reference Hirschl2004; Dixon and Ginsburg Reference Dixon and Ginsburg2017).Footnote 2 Constitutional courts may seek to build their power by taking on increasingly larger caseloads, seeking to weigh in on important political and legal matters arguably beyond their purview (in the process pushing out alternative sites of adjudication or establishing a new judicial hierarchy), and developing “constituencies” that help to shield them from unfavorable political actors (Landau 2014).Footnote 3 These works give us a clear sense of the “high politics” of constitutionalism, but they tell us less about how constitutional law comes to impact everyday citizens or how citizens come to make constitutional rights claims.

This book explores the phenomenon of constitutional embedding, or how we move from constitutions as window dressings or parchment promises (Carey Reference Carey2000) to constitutions that shape both the social and legal expectations of all citizens, not just those who view themselves as benefiting from the constitutional order.Footnote 4 I focus specifically on the embedding of social constitutionalism, a form of constitutionalism that commits the state to the protection of access to social welfare goods, like healthcare, housing, and education, and offers citizens the opportunity to make legal claims to those goods (Brinks, Gauri, and Shen Reference Brinks, Gauri and Shen2015). Varun Gauri and Daniel Brinks (Reference Gauri and Brinks2008) study claim-making within the context of social constitutionalism, though their approach focuses on how expectations about the future encourage or discourage individual and group efforts at legal mobilization. By contrast, I examine how legal mobilization propels constitutional embedding, in the process reshaping possibilities for future claim-making.

Legal mobilization is not the only mechanism that catalyzes constitutional embedding. For instance, effective civic and legal education campaigns may also shape or solidify both social and legal understandings, in turn altering expectations about the function of constitutional law. The same goes for more diffuse social processes by which particular constitutional provisions come to be understood as fundamental to citizenship. Consider, for example, the place of the “right to bear arms” in common discourse in the United States. Litigation has not been the main driver of this discourse; instead, individuals and groups have mobilized around this right both politically and socially, through the National Rifle Association and outside of it, and, over time, for at least part of the population, the right to bear arms came to be understood as a core component of American citizenship and American nationhood.

My goal is not to fully catalogue all possible mechanisms of constitutional embedding. Instead, I aim to demonstrate how, under certain conditions, legal mobilization can be an efficient driver of constitutional embedding that can overcome significant challenges to the embedding process. The rest of this chapter details the concept of embedding and explains the relationship between legal mobilization and constitutional embedding.

2.1 What Is “Constitutional Embedding?”

There are robust literatures across disciplines and subfields that use some variant of the term “embeddedness.” International relations and international law scholars have used the term embedding to refer to the degree to which international legal covenants and dispute resolution mechanisms are present or bolstered in domestic legal frameworks (Keohane, Moravcsik, and Slaughter Reference Keohane, Moravcsik and Slaughter2003; Helfer Reference Helfer2008; Elkins, Ginsburg, and Simmons Reference Elkins, Ginsburg and Simmons2013; Alter Reference Alter2014).Footnote 5 Embedded liberalism (Ruggie Reference Ruggie1982) or embedded markets (Polanyi Reference Polanyi1944) emphasize the ways in which societal ideas and expectations about the economy shape political outcomes.Footnote 6 In this book, I shift the level of analysis and use more specific terms (constitutional embedding, legal embedding, and social embedding). Rather than examining the relationship between the international and the domestic, I look to the relationship between national-level context and societal actors. I am also concerned with disentangling the formal or parchment changes in law from the informal changes in everyday practice – and the relationship between the two.

Constitutional embedding refers to the process by which a particular vision of constitution law comes to take root in everyday life.Footnote 7 It is helpful to think of constitutional embedding along two dimensions: social and legal, or how individuals and groups operating in the social sphere understand and relate to the constitution, and how those working in the formal legal sphere do so.Footnote 8 Social embedding occurs when (1) everyday people develop a set of beliefs about the constitution, (2) “rights talk” enters the vernacular and does so with respect to specific rights and legal tools that can be used to claim rights, and (3) folks actually make legal claims to their rights. This vernacularized understanding of rights may or may not map on to the technical scope of the law. When we talk about an “overly litigious” society, we are talking about a situation in which some vision of law has become socially embedded. The implicit claim is that social understandings of law are wider than legal ones – in short, litigation is occurring at a high rate because of social demands rather than legal appropriateness. When some vision of constitutionalism is socially embedded, people may turn to law for a variety of reasons: out of hope, despair, resignation, cunning, or ambivalence. In this context, people share a common frame of reference, but not necessarily a common interpretation of that frame. At the individual level, the turn to law may or may not be habitual or reflect buy-in (Lovell Reference Lovell2012), but at the societal level, it becomes seen as normal, expected, necessary, or just part of life. When constitutionalism is not socially embedded, those who we might call – drawing on the language of Patricia Ewick and Susan Silbey (Reference Ewick and Silbey1998) – “true believers” and “savvy gamers,” as well as those who have law thrust upon them (Zemans Reference Zemans1983), may still turn to law to make and contest claims, but the place of law is less central and less firmly established overall.

Legal embedding occurs when (1) new legal institutions, mechanisms, and actors come to make their presence known in the daily work of law, and when (2) judges establish, alter, and – especially – expand precedent related to the particular vision of constitutional law. Further, while there may still be some differences of opinion within the legal profession, (3) the mainstream view among active lawyers and judges must be that this vision of law is generally viable and appropriate (e.g., that social rights are not nonjusticiable) in order for there to be legal embedding, including those who work at levels below the high courts. Among the legal profession, skeptics may remain, though their voices will become more and more marginal within the community of lawyers who work on the issue areas in question. The extent to which legal embedding is necessary for continued legal mobilization depends on the ease of access to justice. Where courts are more accessible and legal support is less necessary, buy-in from the legal establishment is less important; though, of course, whether or not judges are willing to accept new claims remains key.

In short, we might think of embeddedness as the degree to which something is no longer unusual in social or legal life, or the degree to which something has become part of what shapes social and legal expectations and behavior. Thus, social embedding is similar to a change in legal consciousness (Merry 1990; Ewick and Silbey Reference Ewick and Silbey1998; Silbey Reference Silbey2005) or constitutional veneration (Levinson Reference Levinson1990),Footnote 9 yet it departs from these concepts in key ways. Legal consciousness studies encompass examinations of identity construction, hegemonic state control of society through the law, and the relationship between individual and group consciousness and mobilization decisions (Chua and Engel Reference Chua and Engel2019). While legal consciousness refers to “the ways law is experienced and understood by ordinary citizens” (Merry Reference Merry1985), the social component of constitutional embedding shifts the focus to constitutional law and rights specifically. In the context of newly promulgated constitutions, constitutional law is often described as a way to “refound” the country and emphasize new values and commitments. When people frame their grievances and rights claims in constitutional terms, they are, in effect, linking their demands to a larger political project.Footnote 10 Constitutional embedding departs from constitutional veneration in that while veneration indicates a stable positive attitude about the constitution, the concept of embedding allows a flexibility about the content of the legal vision and the tenor of citizen evaluations. Likewise, legal embedding is related to, but moves beyond, a change in institutional culture or judicial role conceptions (e.g., Hilbink 2008; Nunes Reference Nunes2010a). The reference point is specifically the constitution, and judges may be motivated to work within the constitutional vision for either ideological or strategic reasons.

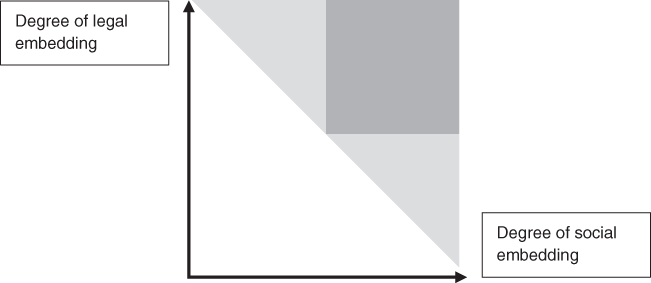

The processes of social and legal embedding are not independent of one another. In fact, they develop recursively and together define how embedded a constitutional order is at any given moment. At the same time, constitutional embedding is not an all-or-nothing game. Uneven or partial embedding is not only possible, but likely. Uneven embedding suggests that there is variation in terms of the constitutional rights that are embedded (a few versus most or all). Partial embeddedness implies relatively more social embedding than legal embedding, or vice versa. In these cases, some components of the constitutional vision, but not others, will become embedded. A context defined by embedding along only one dimension implies that the constitution is less well embedded overall than a context in which both social and legal embedding have occurred. The impact of a partially embedded constitution is likely to be diminished, though it may still shape expectations and behavior around claim-making (on the socially embedded dimension) or judicial behavior (on the legally embedded dimension). Further, both uneven and partial embedding may give way to relatively complete embedding over time, as embedding develops across rights arenas or sectors of society in a piecemeal fashion.

Plotted graphically, we might imagine the degree of social embedding on the x-axis and legal embedding on the y-axis (as shown in Figure 2.1). As you move up and to the right (into the shaded area), a constitution becomes more embedded. We would expect the greatest frequency of mobilization of law in this top right quadrant (dark gray), as the behavior of both social and legal actors reflects the belief that constitutional provisions are meaningful; that citizens can make claims to the rights listed in the constitution. At the top left, we see a high degree of legal embedding without much social embedding. This combination indicates significant changes in law and the expectations of judicial system actors, but negligible changes to societal expectations or discourses. Here, a support structure (Epp Reference Epp1998) can help to ensure that legal mobilization occurs, even if claimants would not by themselves be able to pursue – or be interested in pursuing – social change through the law.

Figure 2.1 Plotting constitutional embedding.

At the bottom right, we have a high degree of social, but not legal, embedding. If citizens talk about social goods as rights, but the legal system does not accept that frame (which would include both the rejection of the possibility of making claims and the rejection of claims once they are made), then we are in the world of this quadrant. This kind of disconnect could occur because of “sterilization by judicial interpretation,”Footnote 11 a term coined by Manuel José Cepeda to indicate active judicial efforts to restrict the meaning or scope of rights, or it could reflect that judges and lawyers are not necessarily opposed but nonetheless have not yet fully embraced this new legal vision. Rights talk may still serve claimants as they mobilize outside the legal sphere (McCann Reference McCann1994), and the continued mobilization within the legal sphere may over time encourage judges to accept the validity of rights claims (Taylor 2020a).Footnote 12 In the bottom left quadrant (not embedded either socially or legally), we have a constitution as that is understood by societal and judicial actors alike as a set of parchment promises or as otherwise insignificant. While an unembedded or weakly embedded constitution may become more embedded over time, the longer a constitution remains unembedded, the less likely it is to ever structure social and legal expectations.

The positioning of social and legal embedding is at no point fixed, and it will likely differ substantially subnationally and across categories of difference (e.g., social or racial groups, class). State presence can vary dramatically between more central and more peripheral locales (O’Donnell Reference O’Donnell1993; Heller Reference Heller2013; Kruks-Wisner Reference Kruks-Wisner2018). Further, numerous scholars have documented how the experiences of race–class subjugated communities, for example, are defined by the coercive rather than protective or distributive capacities of the state (e.g., Soss and Weaver Reference Soss and Weaver2017; Rothstein Reference Rothstein2017; Alexander Reference Alexander2010; see also McCann and Kahraman Reference McCann and Kahraman2021). These social experiences and the state’s orientation toward these groups will condition both components of constitutional embedding. Turning to temporal dynamics, at the moment of drafting, constitutions will not yet be embedded (for anyone). Social and legal embedding might proceed quite quickly after the promulgation of a constitution, or these processes may stagnate.

Constitutions or constitutional orders can become dislodged in a variety of ways, including challenges related to workload, powerful interests, and the scope of the law. Each type of challenge impacts both social and legal embeddedness. Work-related challenges have to do with the new labor created by this new constitutional vision. Judges must hear new kinds of claims (sometimes an extremely large number of these claims). The workload itself may prove difficult for judges to keep up with, and the new content of claims may cause additional complications, especially if judges do not feel that they have adequate training to decide cases on these new matters. This situation presents a challenge to legal embedding to the extent that judges decide cases imperfectly, offer contradictory decisions, or otherwise undermine precedent and shared understandings of the law. When citizens have negative experiences, especially ones that do not align with social expectations of the way that rights and the law ought to function, these experiences can also undermine social embeddedness. Ideational buy-in from judges, fear of sanctions, and additional training and other measures to reduce the workload (such as the hiring of new judges) can help mitigate the potentially destabilizing impact of these challenges.

Actors both within and outside of the formal legal system may also present challenges to the embedding or stability of the new constitutional order. As the new constitutional order empowers certain actors – like judges, especially Constitutional Court justices, as well as different sectors of society – those who object to the constitutional vision or those who are relatively disempowered by it may attempt to limit or delegitimate the order. For example, actors within the executive or legislative branches may refuse to comply with court orders or they may draft legislative acts that would restrict the courts or reshape the scope of existing legal tools. These actors might also criticize the courts and their interpretation of rights in the media. To the extent that they are successful in sowing seeds of doubt about or generating disdain for the constitutional project, these can impede or even dislodge both social and legal embedding. Those empowered by this new vision of law can contest these power-related challenges, particularly if they are able to build constituencies (Landau 2014) or coalitions of support.

Finally, there are limits (though they are perhaps quite flexible at times) to the kinds of problems that are legible to the law. Some problems are easier to document and describe in ways that are compatible with legal system processes than others, for instance where there is a specific harm that is directly attributable to some identifiable actor. More diffuse problems – both in terms of their causes and effects – are more difficult to package in the language and procedures of law. Those whose problems fall into this latter category may see a yawning gap between their lives and the value of the rights they are purported to have. As they are left behind or frozen out, they may come to see law and rights as less than relevant in their lives, or at least as insufficient to remedy their problems. This perception presents a challenge to social embedding (in addition to normative concerns about equal or equitable treatment under the law or realizing the transformative potential of the new legal order). Citizens and organizations may offer creative legal arguments in favor of broader rights protections or judges may expand rights protections of their own accord in response to this challenge, but neither of these responses is guaranteed. Further, these responses present a new potential stumbling block for legal and social embedding if they exacerbate conflicts with political actors or if these efforts lead to an overexpansion of the promises of law (but not the delivery of remedies) and citizens come to view rights and law as empty promises.

Working against these challenges to the embedding of constitutional law is legal mobilization. When patterns of legal mobilization become self-reinforcing, constitutions come to be embedded both socially and legally in such a way that prevents or at least limits the dislodging of a constitutional order – a process described in detail in Section 2.2. The endpoint of constitutional embedding, however, is not the full realization of rights or a rights utopia, but the large-scale transformation of politics, such that politics are processed through the lens of constitutionalism.

2.2 Legal Mobilization as a Mechanism of Constitutional Embedding

Patterns in legal claim-making and judicial decision-making determine the extent to which social constitutionalism remains a parchment promise and the extent to which it comes to be a defining feature of citizens’ everyday lives. In this section, I draw on a constructivist perspective on legal mobilization, which helps illuminate how current interactions between claimants, intermediaries, and judges shape future possibilities for legal claim-making, by influencing both institutional rules and societal expectations (McCann Reference McCann1994; Vanhala Reference Vanhala2010; Taylor 2020a). Through this lens, the key role that legal mobilization can play in embedding constitutions becomes evident. In what follows, I first discuss the concept of legal mobilization, before detailing the social construction of legal grievances and the development of judicial receptivity. I close with a demonstration of the relationship between legal mobilization and constitutional embedding.

2.2.1 What Is Legal Mobilization?

Definitions of legal mobilization abound. For instance, Frances Zemans (Reference Zemans1983: 700) suggests that “[l]aw is mobilized when a desire or want is translated into a demand as an assertion of rights,” while Richard Lempert (Reference Lempert1976: 173) offers that legal mobilization refers to “the process by which legal norms are invoked to regulate behavior.” More recently, Lisa Vanhala (2011) has proposed that legal mobilization encompasses “any type of process by which an individual or collective actors invoke legal norms, discourse, or symbols to influence policy or behavior.” Scholarship on legal mobilization has proliferated, though often in the absence of a clear operationalization of the term and not always in a coherent, additive research agenda.

When I refer to legal mobilization, I mean the explicit, self-conscious use of law involving a formal institutional mechanism (Lehoucq and Taylor Reference Lehoucq and Taylor2020: 168).Footnote 13 In other words, legal mobilization corresponds to claim-making practices in the formal legal sphere, whether individual (Zemans Reference Zemans1983) or collective in nature (Burstein Reference Burstein1991). Legal mobilization implicates an internal process (of defining a grievance or a struggle in terms of legal language or symbols) and an external process (of sharing that understanding with outside actors). The actions encompassed by the term legal mobilization then include administrative procedures, quasi-judicial procedures (such as those complaints processed by human rights or gender commissions and ombudsman’s offices), and legal procedures (litigation). The focus on legal claims made in the context of formal institutions rather than any number of activities potentially related to law – such as bargaining in the shadow of the law (Mnookin and Kornhauser Reference Mnookin and Kornhauser1979) or using the discourse of rights in everyday settings to frame problems as legal in nature – facilitates careful comparison across contexts, assuring that the comparisons involve like units. Further, rights talk may or may not coincide with legal claim-making, and a conceptualization of legal mobilization that distinguishes between the two allows for the probing of whether or not they occur together.

Legal mobilization is a form of political participation. Legal claims in the aggregate (if not always individually) reflect disagreements about the proper distribution of resources and about the proper way or ways in which societal actors ought to interact, thus they imply political demands (see, e.g., Zemans Reference Zemans1983; Marshall Reference Marshall1998; Gallagher Reference Gallagher2006, 2017; Gallagher and Yang Reference Gallagher and Yang2017; Taylor Reference Taylor2018; Kim et al. Reference Kim, Stern, Liebman and Wu2021), as well as particular understandings of the rights of citizens and obligations of states. Legal mobilization can involve a wide array of agents acting in apparently independent ways without overt political motive. These agents may not view themselves as mobilizing law, but collectively they are part of the mobilization of law, and that mobilization has consequences for politics, for who gets what, when, and how (Lasswell Reference Lasswell1936).

2.2.2 How Can Legal Mobilization Serve to Embed Constitutionalism?

By looking to the process of legal mobilization, we can make sense of the shift between an initial period of experimental claim-making that comes in the wake of the creation of new, progressive constitutions – a time in which understandings about rights, the law, and state obligations held by both potential claimants and judges are unsettled – and later, more established patterns of claim-making and judicial decision-making.Footnote 14 This shift involves (1) the social construction of specific issues as legal grievances and (2) the development of judicial receptivity to particular kinds of claims through a reinterpretation of the meaning and scope of fundamental constitutional rights. Under certain circumstances, the combination of these processes can result in a positive feedback loop, with one catalyzing the other. If potential claimants come to view an issue as a legal grievance, they are more likely to engage in legal claim-making around that issue. Those efforts as legal claim-making can prompt judicial receptivity, especially when judges are also exposed to the underlying issue in their everyday lives. Where legal claim-making is met with judicial receptivity, this both confirms the sense that the issue is a legal grievance and prompts further claim-making, resulting in a positive feedback loop. Thus, patterns of legal claim-making (especially claims regarding the right to health, as shown in Chapters 4 and 5) can become solidified over time, which is exactly what occurred in Colombia. At times, however, this pattern will be interrupted, leading to partial embedding or the dislodging of an embedded constitution.

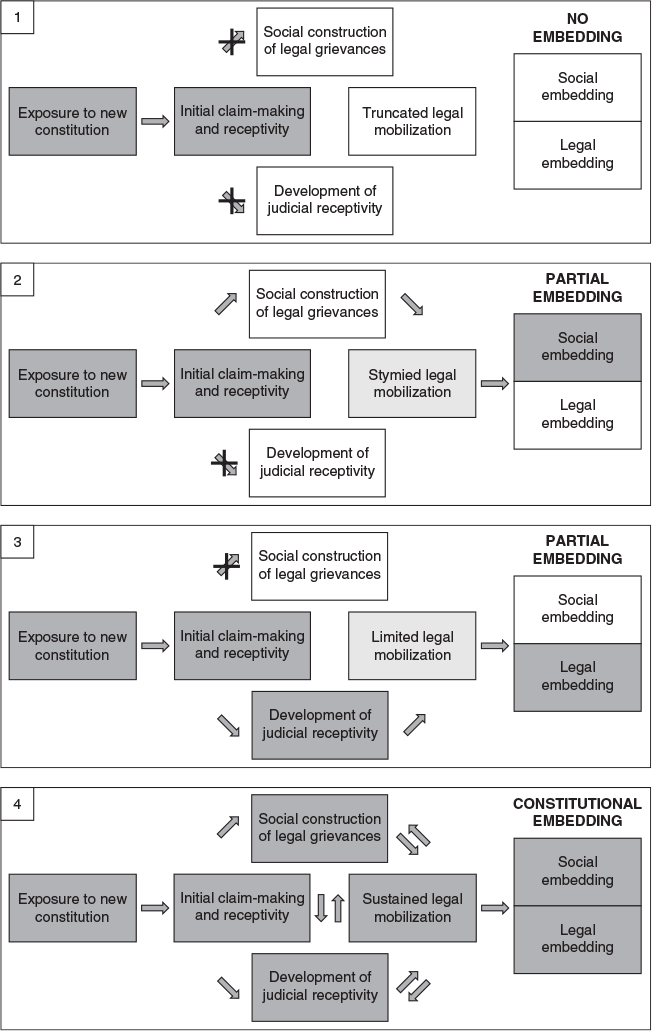

The four panels in Figure 2.2 provide a stylized illustration of the four possible end points of constitutional embedding through legal mobilization: no embedding (Panel 1), two variants of partial embedding (Panels 2 and 3), and embedding (Panel 4). Panel 1 depicts what happens when neither the social constitution of legal grievances nor the development of judicial receptivity to particular kinds of claims occur: following the introduction of a new constitution, some folks may engage in experimental claim-making, but this claim-making will stagnate, with no positive feedback dynamics developing. Under these conditions, constitutional embedding will not occur. Panel 2 shows that the social construction of legal grievances may occur without the concurrent development of judicial receptivity. Here, citizens’ understandings of the law and their problems will change, but their claims will be stymied in the courts: social embedding, but not legal embedding will occur, rendering constitutional embedding partial. Panel 3 shows the inverse, legal embedding without social embedding. In this case, judges may be receptive to particular kinds of claims, but few claims will be brought before them. Once again, partial embedding results. Panel 4 tracks the full process of constitutional embedding, where the social construction of legal grievances and development of judicial receptivity feed into and reinforce one another, propelling sustained legal mobilization and both social and legal embedding.

Figure 2.2 The process of constitutional embedding.

While the Colombian case follows the self-reinforcing logic shown in Panel 4 of Figure 2.2 – where both social and legal embedding occur – this pattern will not always result. If initial, experimental legal claim-making is met with little receptivity on the part of judges or broader society, the constitutional vision may quickly fade from everyday life, such that ultimately it is merely words on paper. Citizens may push for rights protections by way of other strategies or they may not. Middle-ground outcomes, in which constitutions are neither fully embedded nor largely irrelevant to legal or social life, are also possible. Where social and legal visions of the constitution do not overlap, we may see partial embedding. Here, positive feedback loops do not form. Social embedding without legal embedding may still propel citizens to advance legal claims, and legal embedding without social embedding may lead to judges issuing rights-protective decisions for the limited claims that come before them. This partial embedding will be less stable and more prone to fragmentation than combined instances of legal and social embedding.

Further, under the right conditions, legal mobilization can even lead to negative feedback effects and the dislodging of a constitutional order. Social embedding – especially when driven by state-sponsored outreach efforts – can raise expectations among claimants about both the way the legal system will work and the effect their claim-making efforts will have. When citizens are encouraged to file claims and those claims are summarily dismissed or met by judges who hold a conflicting understanding of the law, legal mobilization may undermine the embeddedness of constitutional law. If a regime has sought to use constitutional law and rights rhetoric for legitimation purposes and set up incentives for judges to limit rights protections (Whiting Reference Whiting2017, forthcoming; Kim et al. Reference Kim, Stern, Liebman and Wu2021), citizens may develop what Mary Gallagher (Reference Gallagher2006) calls “informed disenchantment” or what Marc Hertogh (Reference Hertogh2018) describes as “legal alienation.” Here, the experienced disconnect (between visions of law held by potential claimants and visions of law enacted by legal actors) cuts against embeddedness, showcasing the contradictions and tensions of law rather than its promises.

This majority of this book focuses on the “positive” case of successful constitutional embedding in Colombia, exploring how this one particular outcome developed and the moments at which embedding seemed less likely and less possible.Footnote 15 Chapter 9 presents a short case study of constitutional embedding in South Africa, where the 1996 Constitution came to be embedded firmly along the legal dimension without similar depth of embedding along the social dimension. Before turning to the case studies in these later chapters, the rest of this chapter explores the social construction of legal grievances and the development of judicial receptivity – processes set into motion by legal mobilization that can then drive constitutional embedding. The chapter closes with an explanation of how these two processes interact with one another.

2.2.2.1 The Social Construction of Legal Grievances

In order to understand how certain issues come to be understood as potentially claimable in the formal legal system and how these understandings solidify into patterns over time, we must look to (1) the transformation of beliefs about rights and law, as well as (2) the role of societal actors in framing everyday problems as legal in nature. I describe this process as the “social construction of legal grievances,”Footnote 16 a term that emphasizes the ideational and interactive elements of this process.Footnote 17

The ways that citizens learn about their rights as new, progressive constitutions are debated, drafted, and implemented are important for understanding the transformation of beliefs about rights and law. This transformation is likely to be a slow process. The institutional changes implied by the adoption of new constitutions are meaningful only insofar as citizens actually engage them. Stated differently, opportunity for mobilization emerges not when rights are codified, but when (at least some) citizens gain awareness of these rights and believe that they can make claims to them. What is important is not only the accumulation of accurate knowledge about the Bill of Rights or the legal process, but more specifically the development of a set of beliefs about the nature of rights and the purpose of the legal system, as well as the understanding that claims to those goods or services can or should be advanced in legal forums.

Many different sets of actors – including some who are traditionally associated with the legal system and some who are not – will be involved in this process. I highlight how societal actors – a catch-all term referring to those actors not employed in or by the formal legal system, including pharmaceutical and insurance companies, advocacy networks, NGOs, and community organizations – impact views on which issues are ripe for legal claim-making and which are not. Societal actors play an integral role in legal mobilization, not only materially supporting claimants in their efforts to seek redress but also actively contributing to the social construction of grievances by helping to frame certain issues as legal grievances. In other words, societal actors encourage potential claimants to view a specific problem through the lens of the law and to make claims in the formal legal system rather than doing nothing or advancing a claim in some other setting.

Many investigations of mobilization either assume that grievances are based on “underlying activity” (following Casper and Posner Reference Casper and Posner1974) or are simply ever present (following McCarthy and Zald Reference McCarthy and Zald1977). Other accounts typically fail to articulate a stance on where grievances come from and how actors recognize something as a grievance. A constructivist approach, in contrast, acknowledges that grievances, and especially legal grievances, develop through social interaction, rather than appearing unmediated as a result of material conditions (see also Simmons 2016). As activists, lawyers, judges, and government officials participate in the framing of an issue as legal in nature (by advancing such a frame, accepting it, or failing to contest it), this legal frame may spread and come to be incorporated diffusely into everyday understandings of the issue in question (McCann Reference McCann1994; Pedriana Reference Pedriana2006; Vanhala 2016, 2018a, 2018b).

There is also a more direct process by which NGOs, legal aid services, and other actors reach out to individuals who have a particular problem and argue that their problem is a legal one, which should be addressed in the formal legal sphere. This kind of action is most clear in strategic litigation campaigns, but it is potentially much broader than that. In fact, in the case of health rights claims in Colombia, insurance companies that were targeted in legal claims ultimately came to encourage legal claim-making in this direct fashion, as the legal cases counterintuitively offered these companies the possibility of financial gain rather than sanction. Another variant of this process involves NGOs and legal aid services convincing potential claimants to actually pursue litigation, vouching that there is a viable argument and reasonable chance of winning. Through these processes, potential claimants come to view issues that previously they were willing (or resigned) to ignore or to deal with in other ways as legal issues or as legal grievances. Here, the material reality of people’s lives does not change, but their understanding of that reality does.

Only by examining beliefs and repeated interaction between potential claimants, judges, and societal actors can we understand the social construction of legal grievances. These beliefs are constructed and reconstructed through a dynamic and interactive process in which various actors contest the boundaries of what issues are considered to be legal in nature. These societal actors influence the social construction of legal grievances, which then feeds into patterns of legal claim-making. Beliefs about rights and the law, thus, impact claim-making beyond rights knowledge or rights consciousness. But the social construction of legal grievances is only one of the factors feeding into continued legal mobilization; how judges respond to claims is also important.

2.2.2.2 The Development of Judicial Receptivity

In order to understand how judicial receptivity to particular kinds of claims emerges and solidifies over time, we must look to (1) the relationship between judicial agency and shifts in institutional rules, as well as (2) the impact of societal actors and daily life on how judges understand the nature of the problems that come before them in the form of legal claims (Taylor 2020a, 2023). The exercise of judicial agency can entail the creation of new rules, tests, and standards regarding rights protections. When this possibility of the exercise of judicial agency combines with the public exposure of judges to problems, judicial receptivity to particular kinds of rights claims can result, leading to the embedding (or not) of a particular constitutional order.

In short, judicial agency refers to actions undertaken by judges as they fulfill their judicial functions: they decide cases, and in doing so, they interpret law that is often ambiguous. Further, they must make decisions in their nonneutral social environments, and these decisions have political consequences. As such, judges ought to be conceptualized as situated political actors. Judges make choices about which cases to hear and how to decide the cases they do hear, and these choices have potentially long-lasting and unforeseen consequences. Perhaps most importantly, judges make these choices in specific social contexts.

By looking to role conceptions, attitudes, and strategic incentives, existing scholarship on judicial decision-making seeks to explain the kinds of choices judges make. Importantly, though, with each decision a judge takes, they could have chosen otherwise. If a judge (1) holds progressive attitudes about rights, (2) envisions their role as one that protects the rights of citizens, and/or (3) sees an opportunity to expand the power of the courts, they may issue a rights-protective decision in a given case. Still, the judge has leeway in how to delimit the decision and what legal foundation to rely on, among other things. They must offer reasons for their decisions, but there may be many potential reasons for any particular decision. And, of course, judges may instead view their roles narrowly, have rights-restrictive views, and/or face incentives to deny rights claims – and they may issue their rights-restrictive decisions in a variety of different ways.

Judges can shape opportunities for legal mobilization by changing understandings about and uses of preexisting institutional arrangements, through the contingent exercise of judicial agency. This exercise of judicial agency is likely to be particularly influential in the moments during and following constitutional transition, where understandings of rights, state obligation, and the role of judges are unsettled. Contingent choices made by judges during these periods will have outsized effects on questions of justiciability and can serve to either institutionalize and embed constitutional models or erode them.

Importantly, judicial receptivity is not static and it does not fall solely within the domain of judges; instead, it is dynamic and the consequence of repeated interactions between judges, claimants, and societal actors over time. Existing studies have identified two pathways through which societal actors can influence judicial receptivity to particular claims: changes in argumentation about points of legal interpretation and changes in personnel. With respect to argumentation about legal interpretation, Amanda Hollis-Brusky (Reference Hollis-Brusky2015), Ezequiel González-Ocantos (2016), and Tommaso Pavone (Reference Pavone2022), in studies of the Federalist Society in the United States, transitional justice in Latin America, and domestic use of European law in European Union countries, respectively, show how civil society organizations can play a pedagogical role, introducing and supporting new arguments about rights or interpretation to sympathetic judges.Footnote 18 They further demonstrate that societal actors may focus on personnel changes, advocating for the replacement of opposed judges and for the nomination of favored judges.

I identify an additional pathway at play in the context of the development of social constitutionalism: public exposure to problems. This pathway involves a joint public and legal process, where an issue becomes visible to judges in their lived experience outside the courtroom as well as legible to judges as legal in nature. Judges may come to believe that this legal problem is not being dealt with well or sufficiently in the context of the legal system. They then may become more open to new legal approaches to the issue. The exposure mechanism differs from the argumentation mechanism in that judges are not swayed by new legal arguments. Instead, the persistence and/or increase of claims related to a specific grievance cumulatively inform judges about an issue, making them comfortable with the scope of the issue, making them more aware of the issue’s salience, and making them identify with claimants. This can spark a consideration or reconsideration about the correct legal response to that issue – and therefore those claims. Although Malcolm Feeley and Edward Rubin (Reference Feeley and Rubin1998: 160) examine judicial policy-making rather than legal mobilization, they identify a similar process at play in their analysis of the judicial response to reprehensible prison conditions in the United States, suggesting that “these conditions had existed for a century, of course; what changed suddenly, in 1965, was the judiciary’s perceptions of them.” Here, continued claim-making (and thus continued exposure) ultimately prompted a change in judicial receptivity.

Breaking this process down, an initial confluence of exposure in daily life outside the legal system and exposure within the legal system plays an important role in the development of judicial receptivity, inspiring judges to connect an issue that they have perhaps seen on television or in their everyday lives with the format, scope, and tools of the law. Repeated exposure to similar cases within the formal legal system can have several concrete effects. As Julio Ríos-Figueroa (Reference Ríos-Figueroa2016: 29) outlines, where there is a “continuous flow of cases [judges] will not only get more and more varied information, but will also be more able to express their jurisprudential preferences under more favorable circumstances.” By contrast, if there are only a handful of cases on a particular topic over a longer period of time, judges will have less flexibility in their decision-making, as they are bound by the facts of the cases before them and may be forced to decide cases in unfavorable political environments. The mere existence of many cases does not necessarily mean that judges will seek to resolve those cases in novel ways. In fact, repeated exposure alone could result in a hardening of judges’ views (Kim et al. Reference Kim, Stern, Liebman and Wu2021). This is where an additional factor comes into play: assessments of the nature of the issue and how it comports with sociolegal values.Footnote 19 When judges view the issue as oppositional to contemporary sociolegal values, such as country-specific understandings of dignity, exposure can result in judicial receptivity, as judges come to see the issue not only as one that could be resolved in the formal legal sphere, but also as one that needs to be resolved.Footnote 20

Judges’ beliefs about rights and the state, which are conditioned by their personal experiences, as well as by interactions with claimants and actors outside of the formal legal sphere, are key to understanding patterns in legal mobilization. These beliefs and interactions shape the contours of judicial receptivity, encouraging judges to issue rights-protective decisions in certain kinds of cases and not others. Further, by issuing decisions on legal claims, judges alter opportunities for mobilization. Especially when they (or other actors) publicize these decisions and the reasons underlying them, judges also influence social understandings of which issues are legal in nature – in other words, judicial receptivity also influences the social construction of legal grievances. When social and legal visions of the new constitution overlap, positive feedback loops can form, with the social construction of legal grievances and the development of judicial receptivity bolstering each other, which in turn incentivizes sustained legal mobilization and serves to propel constitutional embedding.

2.3 Conclusion

This book examines how constitutional rights become “real,” or how the promises written into constitutions come to have social and legal meaning, and thus shape the behavior of both everyday citizens and judicial system actors. Key to this process is the development of both the social and legal dimensions of constitutional embedding through legal mobilization. When these two dimensions of embedding reinforce each other – as judges, lawyers, everyday citizens, and various other societal actors come to share the same vision of the possibilities and limits of constitution law – a constitutional order will be difficult to dislodge.

Legal mobilization can drive the construction of this shared vision. Following the adoption of new constitutions that recognized a wide set of rights, citizens gradually come to learn about these rights, and they begin to take some of the problems in their lives to the formal legal system, experimentally. Some of the time,Footnote 21 this experimental claim-making solidifies into general patterns in claim-making, as citizen come to view particular issues as legal grievances and as societal actors – ranging from NGOs engaged in rights-based activism to insurance companies that sought to offload costs – encourage further claim-making. Simultaneously, judges’ beliefs about their role and the applicability of the law to social issues change, in part because of the way that legal claims and daily life combine to expose them to these problems. As judges continue to decide cases, the terrain of opportunity for further claim-making shifts.

Where sustained legal claim-making on a particular issue (following the identification of the issue as legal grievances) prompts judicial receptivity by exposing judges to that issue, positive feedback loops form and legal mobilization becomes self-reinforcing. Receptivity then inspires further claim-making. This is especially true when judges signaled the kinds of arguments or claims they were most likely to evaluate favorably by staging pedagogical interventions or offering “cues” (Baird Reference Baird2007) to potential claimants, in the process spreading information to potential claimants about the kinds of arguments or claims likely to be accepted. Thus, the process of legal mobilization can serve as a mechanism of constitutional embedding, with the iterative process of claim-making in the formal legal sphere shaping how both everyday citizens and legal actors understand what the law is and does – or what the law ought to be and what it ought to do.

Wholesale constitutional embedding is not a preordained outcome; nor will it necessarily result from legal mobilization. Constitutional embedding develops over time. It can occur steadily or in fits and starts, and once the process is started, it can develop unevenly or partially. Uneven embedding describes constitutional orders where some rights or provisions come to be meaningful while others lag. Partial embedding refers to the occurrence of a greater degree of legal embedding than social embedding, or vice versa. Partially embedded constitutional orders are more likely to be derailed than constitutional orders defined by both social and legal embedding. Subsequent chapters explore how social constitutionalism came to be embedded both socially and legally in Colombia and how challenges to that embedding were overcome.