Scholars have long noted how law can both enable and constrain those who wish to contest existing power relations (e.g., Scheingold Reference Scheingold1974; Thompson Reference Thompson1975). While elite control of the drafting of legal rights and regulations and over the operation of legal institutions may result in the perversion of the supposedly even-handed law, this codification, this formalization, and this claim to fairness and justice at times can empower nonelites and work against those in power. Still, though “rights talk” may offer new opportunities to claimants or to movements in their myriad quests to improve the conditions of their lives, the very invocation of rights may legitimate an illegitimate state or further embed a hegemonic discourse, reifying existing power relations (see, e.g., Glendon Reference Glendon1993; Nonet and Selznick Reference Nonet and Selznick2001; Silbey Reference Silbey2005). However, as many scholars have documented, these concerns may have been overstated as individuals and movements deftly and selectively use rights talk and legal tools in pursuit of their goals (McCann Reference McCann1994; Ewick and Silbey Reference Ewick and Silbey1998; Epp 2009; Lovell Reference Lovell2012; Taylor Reference Taylor2018).

These questions about elite machinations and counter-hegemonic possibilities can overshadow fundamental questions about lived experience. All too often, everyday discussions of law and social change (or politics writ large) are divorced from the ways in which people experience opportunities, constraints, advances, and setbacks. Yet, as Robert Cover (Reference Cover1986: 1601) rightly proclaimed, “legal interpretation takes place in a field of pain and death.” Far from simply being parchment promises, social rights recognitions make clear that Cover was right that legal interpretations of the scope, meaning, and content of social rights have life and death consequences. For those without access to health, housing, food, water, sanitation, and other social welfare goods, life is remarkably insecure. Absent a fundamental level of access to welfare, individuals cannot participate fully in political, social, or economic life.

The Social Constitution explores how law influences lived experience, from the everyday to the exceptional, as well as the meaning of rights and the ways in which people struggle to improve their lives. In this book, I look to the constitutional codification of social promises as rights and then track how citizens work to make claims to those rights, how judicial officials respond, and the forces that work against significant rights claim-making. The widespread constitutional recognition of social rights and the empowerment of courts to hear claims to those rights came to the fore during the third wave of democratization and the height of neoliberalism; yet, it set out a new, dramatically different understanding of state obligations and the interaction of the state, markets, and citizens. Social constitutionalism creates opportunities for citizens to make new types of claims to social goods – but only to the extent that the Constitution and its vision of law become something more than words on paper; only to the extent that the Constitution becomes embedded in social and legal life.

This book detailed the process of constitutional embedding, or the conditions under which particular visions of law come to take root both socially and legally. The social component of constitutional embedding (the focus of Chapter 4) occurs when rights talk has entered the vernacular and does so with respect to specific rights and legal tools that can be used to claim those rights, while the legal component of constitutional embedding (the focus of Chapter 5) occurs when judges establish, alter, and expand precedent related to a particular vision of constitutional law. In short, embeddedness refers to the degree to which something is no longer unusual in social or legal life. Without embedding, law remains a parchment promise, a window dressing, or simply irrelevant. Constitutional rights or constitutional orders can be partially or unevenly embedded, and they can become dislodged or left latent in a variety of ways, including challenges related to the scope of the law, struggles over political power, and the everyday work of processing legal claims. Further, it is possible to see significant legal embedding without equivalent social embedding, or vice versa.

Chapter 6 documents how, despite evidence of significant legal and social embedding in much of Colombia, embedding has not spread to all marginalized communities. Not everyone’s problems are legible to the law. When this is the case, legal mobilization cannot serve to embed a constitutional vision. Chapter 7 explored the tensions that can emerge between actors in favor of and against the new constitutional order. It also shows how continued legal mobilization can protect against powerful challenges to embedding. Chapter 8 examines how the daily work of social constitutionalism can provide challenges to constitutional embedding, and it demonstrates how changes in institutional rules and role conceptions (solidified through legal mobilization) can counteract these challenges. Chapter 9 turns to the case of South Africa to explore a case of the partial embedding of a social constitution, where the new constitutional system has been adopted by and ingrained in legal actors, as well as some NGOs, but not by society writ large.

A focus on constitutional embedding brings to light important questions and avenues for research in the study of law and society, especially legal mobilization and legal consciousness, comparative constitutionalism, and social citizenship. In what follows, I turn first to the possibilities of social incorporation and the deepening of citizenship through law. I then consider the relationship between legal mobilization and organized civil society support. Next, I examine the impact that ambivalence about the law and technically incorrect understandings about the law have on constitutional development and rights realizations. I close with a few words on the applicability of the concept of embedding across contexts, the range of possible embedding outcomes, and the mechanisms that can propel embedding.

10.1 Social Incorporation through Law?

The Social Constitution uncovers how social actors can shape citizenship rights and their enactment or enforcement. It examines how social constitutionalism plays out on the ground over the long term and comes to shape claim-making and access to social welfare goods. In addition, this book demonstrates the utility of viewing legal mobilization as a form of political participation and as an important part of state–society relations, in this case allowing for an investigation of how social constitutionalism impacts access to social services and creates a new mode of social service provision. This mode hinges on the ability and willingness of citizens to make claims to constitutional rights that are universal in theory, though bounded in practice

Studies of social incorporation or the provision of social welfare in developing societies have focused on three dominant models of state–society relations: patron-clientelism (Bratton and van de Walle Reference Bratton and van de Walle1997; Auyero Reference Auyero2001; Chandra Reference Chandra2004; Kitschelt and Wilkinson Reference Kitschelt and Wilkinson2007; Stokes Reference Stokes2013), corporatism (Schmitter Reference Schmitter1974; Collier and Collier Reference Collier and Collier1979; Yashar Reference Yashar1999), or the market alternative (Hall and Soskice Reference Hall and Soskice2001; Adésínà Reference Adésínà2009). Social constitutionalism, by contrast, opens up another path to social citizenship (Marshall Reference Marshall1950). In the context of social constitutionalism, all citizens can turn to claim-making in the courts to attempt to gain access to social welfare goods, regardless of whether or not they have ties to politicians and political parties or the ability to purchase those goods privately.

However, as Sandra Botero, Daniel Brinks, and Ezequiel González-Ocantos (2022: 2) note, “the promise of judicialization [or of social constitutionalism] falls short when the superstructure of judicialization remains unmoored from deeper social and political roots, and when it produces heavy demands that cannot be met by weak states and institutions.” By “the superstructure of judicialization,” they mean “formal institutional and elite cultural changes,” such as constitutional reforms, adoption of regional and global human rights instruments, and the professional incentives within the legal sphere (2022: 13–15). Unless changes to the constitutional text are accompanied by broad social support, the possibilities of social change – whether for the individual or broader society – are severely limited and vulnerable to backlash and regression.

Similarly, Roberto Gargarella (Reference Gargarella2020) warns that twentieth-century constitutionalism in Latin America is not without its flaws. While his seven theses focus on the monsters that Latin America’s “old constitutionalism” gave rise to, Latin America’s new constitutionalism, which largely fits the social constitutionalist model, has not been able to outpace the monsters it creates either: unequal political and economic power endure, and the promises of full representation are, as of yet, unrealized. He attributes this to the dual character, or the “two souls,” of these constitutions. On the one hand, the sections of these constitutions on rights showcase a social and democratic orientation, while the sections on the organization of the state instead privilege elite power and serve to exclude many sectors of society. The existence of these two souls has the effect of creating points of tension that threaten to limit the possibilities of substantive change through constitutional reform. The Social Constitution documents how constitutional embedding can occur, how the judicialization of politics can become moored firmly in a particular sociopolitical context, and how points of tension within a constitutional model can be smoothed over.

Turning now to the Colombian case, what are the material consequences of social constitutionalism for everyday Colombians? The most visible consequence has come in the form of the Colombian Constitutional Court fundamentally reshaping healthcare policy and the healthcare system. The acción de tutela – a legal mechanism introduced by the 1991 Constitution that allows individuals and groups to easily make claims to their constitutional rights – was central to this outcome. In 2008, the Constitutional Court grouped together twenty-two tutela claims and issued a structural decision (T-760/08). That decision called for a restructuring of the benefits plan that would outline which medicines and services had to be covered by the entidades promotoras de salud (which are akin to insurance companies), regulate transfers of administrative costs to patients, and solidify the freedom to choose among healthcare providers. In addition, the decision called for the adoption of deliberate measures to realize universal coverage. The Court has required concrete changes to the healthcare system in other cases as well.Footnote 1

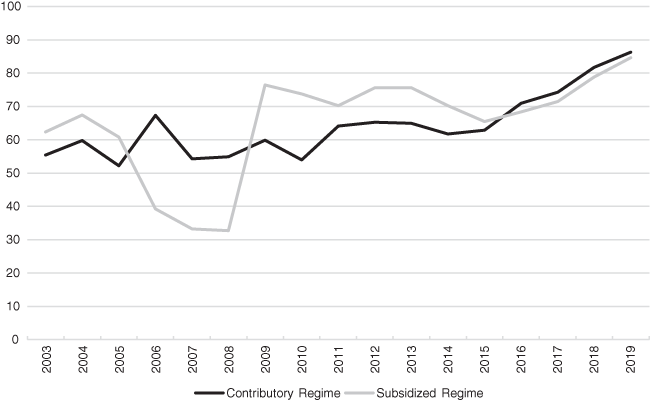

When evaluating the impacts of individual health tutela decisions, however, we must ask whether people are turning to the tutela to demand coverage for procedures and services that are not included in the national healthcare plan, thus expanding spending on health, or whether, on the other hand, they are turning to the tutela to enforce the system as designed and to reduce the incidence of arbitrary and corrupt denial of services. The answer is, “some of both,” though the trend appears to be more of the latter as time goes on. In the early 2000s, when the Defensoría del Pueblo began to collect and publish data on the topic, just under half of all claims were attempts to expand coverage, while half were efforts to obtain access to covered medicines and services. Figure 10.1 shows the percentage of tutelas claiming covered goods by healthcare regime, contributory versus subsidized. Over time, however, the percentage of claims having to do with goods or services officially covered by the national health benefits plan increased to over 85 percent. That is true for both the contributory and the subsidized health systems.

Figure 10.1 Percentage of tutelas for covered goods and services by healthcare regime.

Between 2009 and 2019 (the years for which disaggregated data are available), Colombians filed 1,576,627 tutelas that invoked the right to health. On average, judges found in favor of these applicants 82.1 percent of the time (ranging from a low of 79.7 percent in 2010 to a high of 85.6 percent in 2017). To date, there has only been one study on compliance with tutela orders, which was conducted by Ryan Carlin et al. (Reference Carlin, Castrellón, Gauri, Sierra, Cristina and Staton2022) on tutela claims filed in 2014. The study found a compliance rate of 72 percent. If we assume that the compliance rate has held steady over time (an assumption that should be empirically verified in future studies), then we can conclude that more than 930,000 claimants gained access to medications, appointments, and procedures that otherwise would have remained out of reach.

Even if compliance with tutela orders is less than perfect – again the Carlin et al. (Reference Carlin, Castrellón, Gauri, Sierra, Cristina and Staton2022) study found noncompliance 28 percent of the time – at least some of the time social constitutionalism, when activated by claim-making with the tutela procedure, results in tangible gains in access to the goods and services promised to every Colombian citizen. In other words, social incorporation expands. Additional comparative research, however, is needed to fully probe the promise and limits of social incorporation through social constitutionalism.

10.2 Legal Mobilization without Support?

Much scholarship on legal mobilization has focused on either when and how individuals or movements decide to make claims in the formal legal sphere or when and how judges offer rights-protective decisions. Yet, these processes do not occur in isolation and should be assessed in conjunction with one another. This book demonstrates the value in examining legal claim-making and judicial behavior together, considering how claimants or potential claimants; intermediaries, including lawyers, activists, and actors not typically associated with the legal system, like insurance companies; and judges affect the process of legal mobilization and potential for the embedding of social constitutionalism. Only by expanding our understanding of the roles that different actors play in the process of legal mobilization can we make sense of the complex, recursive dynamics at work.

The book further underscores the need to revisit our understanding of what a “support structure” is (Epp Reference Epp1998), moving beyond shrewd cause lawyers (Scheingold Reference Scheingold1974), resources, and elite connections. In his seminal work, Charles Epp explores the utility of the support structure concept, demonstrating that receptive judges, a strong bill of rights, and a robust rights consciousness alone are not always enough to surmount challenges in accessing the courts and spurring a rights revolution. Subsequent scholarship examined how social movement actors could serve to facilitate the development of a support structure (Cichowski Reference Cichowski2007; Vanhala Reference Vanhala2010).

The Colombian case, however, shows that other sets of actors, including corporations (specifically insurance companies) and even ordinary citizens are also part of the story. Where the “legal opportunity structure” is open and cost of filing legal claims is low, changes in social understandings about formal access mechanisms, like the tutela procedure, can lead to changes in the rules regulating those mechanisms, which in turn can reshape opportunities for claim-making, even in the absence of formal resource support. With the tutela, an individual can initiate a legal claim against a public or private actor without having to pay any fees whatsoever, as the claim can be delivered verbally and does not require the use of a lawyer. Importantly, the claimant does not technically need to articulate a legal argument about their rights; the judge of first instance is tasked with making sense of the situation described by the claimant and determining whether or not a constitutional rights violation occurred. Further, insurance companies and other healthcare providers actively encouraged the use of the tutela and helped to inform citizens about how to make health rights claims. The formal rules regarding the tutela – particularly those on standing, procedure, and costs – enable legal mobilization without the need for a support structure.

Future research should also examine in greater detail the ways in which different features of legal opportunity combine, where the existence of certain features might mitigate the need for others. Are tools such as the tutela necessary or merely permissive for legal mobilization in the absence of a support structure? Under what conditions can claimants self-fund their efforts at legal mobilization and when must they turn to external sources of support? How does the source of support impact the kind of claim made or the likelihood of success?

10.3 Everyday Constitutional Struggles and the Politics of Rights

The Social Constitution highlights the importance of assessing how people understand the conditions of their own lives as well as the lives of their fellow citizens, the rights to which they can legitimately lay claim, and how those understandings shape whether, when, and how constitutions come to be embedded. It drills down to where grand documents, like constitutions, meet the people who interpret them and fight for what they could mean. These struggles over the meaning of rights have profound material and symbolic consequences. They provide the tools for people to not only live, but live well – and to imagine a better life.

As such, the book takes up Stuart Scheingold’s (2004 [1974]) suggestion to consider both the myth and the politics of rights together and Michael McCann’s (Reference McCann1994: 9) call to view the law’s role in political struggle as “expansive, subtle, and complex.” The myth of rights necessarily connects rights and rights claim-making with social change – simply, the myth creates the understanding that rights realizations follow rights litigation. The politics of rights, however, encourages us to think of rights not as “accomplished social facts or as moral imperatives,” but instead “as authoritatively articulated goals of public policy and, on the other, as political resources of unknown value in the hands of those who want to alter the course of public policy” (Scheingold 2004 [1974]: 7). Rights can serve as resources not just to challenge public policy, but also to make and remake the conditions of individuals’ everyday lives. The embedding of social constitutionalism – a process that occurs through the repeated interaction of individuals, movements, judges, lawyers, activists, and even actors we do not normally associate with the formal legal sphere, like health insurance companies – helps to realize a politics of rights, creating toeholds for those who wish to make claims and seek access to social goods. There is no guarantee of success, but there is a chance.

The Colombian case also indicates that the macro-level politics of rights may be informed by a variety of micro-level features, in addition to and beyond strategic considerations regarding when and how to make rights claims. These include deep institutional knowledge without rights consciousness, inaccurate beliefs about both claim-making procedures and the content of rights, and ambivalence about legal claim-making. Chapters 4 and 6 showes how residents of the marginal community of Agua Blanca hold detailed knowledge about the tutela and the Victims’ Law of 2011. They referred to specific provisions and procedures, even when suggesting that these legal tools did not work for people like them. Even under the limited circumstances in which they did work, folks described these tools more as bureaucratic hoops to jump through rather than anything to do with rights.

These understandings can be mobilizing or demobilizing, regardless of their accuracy. Take, for instance, the example from Chapter 4 of the domestic worker who wanted to file a tutela claim to gain access to state benefits for having been displaced. She had not been displaced, and yet, she talked to a judge about filing such a claim. This is evidence that inaccurate beliefs can be mobilizing. Such inaccurate beliefs can even become self-fulfilling prophecies, as social facts reshape institutional rules over time. Many people I spoke with suggested that the tutela could only be used to claim the right to health. There may have been an implied “with any hope of success” at the end of that sentence, but some folks may have firmly believed that the tutela is for health rights claims and nothing else. Either way, something that is not technically true shapes the possibility of claim-making. Future research should further examine the relationship between legal consciousness, legal mobilization, and knowledge, whether accurate or inaccurate.

Further, this book demonstrates that mobilization can be an ambivalent process that is still deeply ingrained and embedded in expectations about how the world works, but neither reflective of buy-in to the myth of rights nor hope in the politics of rights. This ambivalence presents a challenge for how we understand the relationship between legal consciousness and legal mobilization. There is more to it than legal hegemony and unthinking deference on one end of the spectrum and counter-hegemonic discourse and legal alienation on the other (Ewick and Silbey Reference Ewick and Silbey1998; Hertogh Reference Hertogh2018; Halliday Reference Halliday2019). Ambivalence, the perception that there is no alternative (Taylor Reference Taylor2018), and misunderstandings can prompt the turn to law in everyday life. Questions remain, though, about how long these dynamics can remain stable. If folks only see incremental and uneven changes in their lives and they have not bought into a dominant discourse about how law works, will they continue to turn to legal claim-making (and continue to facilitate the process of constitutional embedding)? Can incremental and uneven gains from legal mobilization in one issue area spill over into others? How do potential claimants’ expectations change over time? When might legal alienation emerge from conditions that had been defined by ambivalence, either as an expression of counter-hegemonic discourses or apathy and a turning away from law?

10.4 Constitutional Embedding, a Changing Rights Terrain, and a Defense of Constitutionalism

Around the world, and particularly in the Global South, the 1990s and 2000s brought with them an expanding rights terrain – at times formalized in constitutional rights protections, at times implicated in directive principles, and at times found instead in ordinary legislation. This growth in rights recognitions on paper makes the question of when and how rights become “real” or matter for people’s everyday lives all the more important. Now, thirty years later, we can start to assess the consequences of this expansion.

As Janice Gallagher, Gabrielle Kruks-Wisner and I (forthcoming) document elsewhere, claim-making as a form of political participation has come to be increasingly salient during this period. In the absence of programmatic policies and strong political parties, citizens turn to claim-making in both judicial and administrative forums to try to attain access to needed goods and services. Claim-making, under certain conditions, can have both material and political consequences: not only changing who gets what when, but also reshaping how citizens relate to the state and creating new kinds of institutional spaces available to citizens. The “embeddedness” of law and policy helps us to understand when and how claim-making has these tangible impacts on peoples’ lives.

I hold that under conditions of both social and legal embedding, we see the most significant rights protections. As this book demonstrates, legal mobilization is one mechanism that can initiate feedback processes that result in constitutional embedding. However, legal mobilization is not the only such mechanism. Future studies should focus attention on other ways that different audiences come to learn about rights provisions, find them meaningful, and work to incorporate them into everyday life.

Examples of partial embedding – whether defined by social or legal embedding, but not both, or unevenness in subnational embedding – abound. For example, Chapter 9 explores the case of South Africa, documenting the substantial development of legal embedding without the accompanying social embedding. While some community-based organizations and many lawyer-driven NGOs have turned to constitutional rights claim-making, everyday South Africans have not come to view the Constitution or legal claim-making as central to their lives. Kira Tait (Reference Tait2022) provides a robust account of why social embedding has not occurred, pointing particularly to the “thinkability” (or lack thereof) of legal mobilization among Black South Africans in the province of KwaZulu-Natal. It is not that formal access to courts does not exist, though it is limited, or that the constitutional rights infrastructure is lacking. Instead, people’s “perceptions from their lived experiences or the retelling of others’ experiences encountering the law, its actors, and the broader state,” ranging from allegations of corruption to witchcraft to institutional inefficiencies, inhibit the ability of potential claimants from even imagining the possibility of turning to the formal legal sphere to deal with certain kinds of problems (Tait Reference Tait2022: 3).

In contrast, Janice Gallagher (Reference Gallagher2022) skillfully details how rights protections related to disappearances have become socially embedded in Mexico, while substantive (as opposed to rhetorical) legal embedding has lagged. Those whose loved ones were disappeared have developed a robust knowledge of rights, rules, and procedures and have innovatively used repeated claim-making to try to attain information about what happened and ideally justice and accountability for the disappearances, but the legal sphere has not been receptive to these claims. Social embedding, at least for certain communities, endures despite this disconnect with the formal legal system. Gallagher (Reference Gallagher2022) attributes this to the nature of the grievance: a loved one being disappeared is fundamentally reorienting, and experiences that might otherwise dissuade one from continuing to make claims pale in comparison to that life-shaking event.

Turning to China presents another window into how legal embedding can develop independently of and even at times undercut social embedding. The Chinese state both developed a set of workplace legal protections and actively disseminated information about these new laws to the public. In fact, it attempted to actively use the media to construct the legal consciousness of citizens across the country and across issue areas (Whiting Reference Whiting2017). Workers, in particular, adeptly took up the task of turning to law to protect themselves from rights violations, simultaneously developing a greater sense of internal efficacy and “disenchantment” with the legal and administrative institutions associated with workplace legal protections (Gallagher Reference Gallagher2006, 2017). Chinese citizens also began to engage in “open government information” litigation with frequency, continuing even when their claim-making efforts did not have material consequences. However, judges also attempted to stymie the efforts of the most litigious claimants by creating new legal categories to divert claims away from the legal system (Kim et al. Reference Kim, Stern, Liebman and Wu2021). Unlike the case of health rights in Colombia, judicial receptivity did not develop in conjunction with social understandings of the law. Instead, judges maintained their own understandings of the law, ones that prompted a sense of alienation and a widening disconnect with social actors. Here, we see how the experience of mobilizing law can undermine the creation of a social understanding that these rights are meaningful in themselves. Future research should further explore the subnational terrain of constitutional embedding and the consequences of the various combinations of partial constitutional embedding across contexts.

Today, a wide variety of countries, including Armenia, Belarus, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Gambia, Sri Lanka, Taiwan, Turkey, and Uzbekistan, are currently considering the drafting of new constitutions or the adoption of significant constitutional reforms (ConstitutionNet 2021). Perhaps most notably, in May 2022, the Chilean Constitutional Convention introduced a new draft constitution that recognizes a range of social rights, which is a substantial change from the Pinochet-era constitution being replaced. While Chilean voters rejected this draft constitution via a referendum in September 2022, the debate about the new constitution continues. Following the eventual promulgation of whatever version of the constitution is approved, a pressing question will be: to what extent are the actors in favor of and against the constitutional order (whether new or old) able to embed their visions of constitutional law?

At the same time as these constitutional reforms are being drafted, academics have begun to debate with renewed vigor the merits of constitutionalism itself, regardless of modifiers. To some extent, these arguments revive early critiques of powerful constitutions and powerful courts. For example, traditional accounts of judicial politics highlighted the ways in which courts have protected elite interests rather than the needs of the poor or politically marginalized (Galanter Reference Galanter1974; Scheingold Reference Scheingold1974; Rosenberg Reference Rosenberg1991; Nonet and Selznick Reference Nonet and Selznick2001). Others pointed to the dangers of “counter-majoritarianism” (Bickel Reference Bickel1962), or the possibility that special interest groups representing the preferences of the few win out in the courts at the expense of the interests of the general population. The extent to which social constitutionalism contributes to the deepening of democracy or, in fact, thwarts democratic processes is an open empirical question that is contingent on whether and how social constitutionalism becomes embedded.

These more recent critiques of constitutionalism express skepticism about the value of judicial review, especially in its strong form (Gyorfi Reference Gyorfi2016), and the potential erasure of the lines between national and international bodies and between the power of the judge and elected representatives (Loughlin Reference Loughlin2022). Tamas Gyorfi proposes a theory of weak judicial review, which would allow a role for judges in the specification of rights, but only under the umbrella of an approach that is largely deferential to the legislature would this be acceptable. This kind of review would allow courts to assess whether or not legislation corresponded to structural-organizational norms, rather than a bill of rights. For Gyorfi (Reference Gyorfi2016: 257), “the speculative and marginal improvement in human rights protection [brought about by strong constitutional courts] does not justify the direct, imminent and systematic exclusion of the citizenry from some of the most important political decisions of the community.” As Gyorfi acknowledges elsewhere in his provocation, however, the extent to which either legislatures and courts adequately – or even partially – represent citizens’ interests varies substantially across contexts.

Martin Loughlin (Reference Loughlin2022: 195) laments the demise of a form of constitutionalism that endorses limited government and the emergence of a constitutionalism that would encompass all of social life, “provid[ing] a comprehensive scheme of society” and serving as the “symbolic representation of collective political identity.” That a constitution exists perhaps means that it will provide such a scheme, but it will be impactful only to the extent that it is embedded socially and legally. The embedding process seems to be what Loughlin takes issue with, though arguably embedding is just as democratic (and as anti-democratic) as most other political processes currently up for debate. Embedding occurs not by a formal vote but through “voting with one’s feet,” by citizen action and interaction, sometimes consciously and sometimes subconsciously. All members of the polity can participate, though their ability to participate equally will by heavily mediated by their power and resources (which, of course, are largely determined by socially constructed categories of difference, including race, class, and gender), as is the case with electoral politics.

The implicit alternative to social constitutionalism – with its justiciable individual rights and courts with strong review powers – is the construction of participatory institutions and a strong, representative legislature (which would ostensibly allow for politics to be conducted through ordinary legislation rather than constitutional law). First, these institutions are not necessarily mutually exclusive with social constitutionalism, and second, they are not immune to power differentials or vested interests. Traditional legislatures certainly cannot always be counted on to receive broad public support, avoid elite capture, or operate without dysfunction. Loughlin (Reference Loughlin2022: 197) suggests that “legislatures are now losing authority to governments, regulatory officials, and courts,” which “erodes the principle of popular authorization, simultaneously weakening legislatures and political parties.” However, in many places, including Colombia, the failures of legislatures and parties long preceded the creation of constitutional courts or the move from liberal or limited constitutionalism to the more robust form of social constitutionalism. The rise of the strong courts was not the source of the erosion of public support for the legislature or the failure of legislatures to govern effectively through ordinary legislation. In theory, strong courts and strong legislatures serve as checks on one another, moderating one another. Thus, in some ways, these critiques of constitutionalism are more concerned with how constitutionalism has been embedded in specific places than with constitutionalism itself.

The claim that constitutionalism “has been widely perceived as a positive phenomenon largely because it has never been closely analyzed” is perhaps a fair one (Loughlin Reference Loughlin2022: 22). This book has endeavored to carry out such an analysis. I do not conclude that constitutionalism is an unqualified good. But neither is constitutionalism necessarily at fault for the ills currently plaguing global politics. Constitutions set out rules of the game, but, as this book shows, those rules both reflect and respond to politics on the ground. An embedded constitution can offer citizens a forum through which to pursue their needs, and viable alternatives are often few and far between. The experiment with social constitutionalism will not inhibit the possibility of more radical experiments in the future, but it does provide vulnerable citizens with one more tool – however blunt or ill-formed – with which they can push for changes to the conditions of their lives.

Further, as we see trends toward rights retrenchment elsewhere in the world, from the United States to countries in Africa, eastern Europe, and South Asia, we might well ask, “when and how can societies push against that?” One answer is to ensure that rights – whether codified in constitutional law, directive principles, or legislation – are embedded both socially and legally. When those rights are embedded and routinely claimed through legal mobilization, as the Colombian case demonstrates, they can withstand challenges from those who would wish to unravel them and those who feel no sense of obligation.