The social and legal embedding of the 1991 Colombian Constitution empowered the Constitutional Court with respect to the country’s other high courts and the executive and legislative branches of government, as documented in Chapter 7. These other actors at times challenged the constitutional order and sought to reshape the relative power of the Constitutional Court and the tutela procedure. Thus far, though, these challenges have not been sufficient to dislodge social constitutionalism in Colombia.

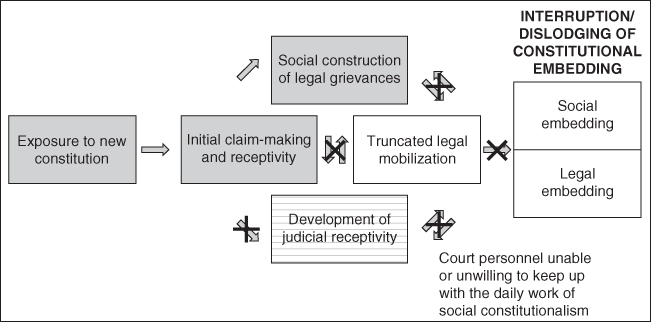

This chapter turns to an additional set of challenges created by the advance of social constitution and the broadened role it entails for ordinary judges. Ordinary judges are tasked with the daily labor of hearing tutela claims in the first and second instances on top of their other duties. Not only does the tutela bring more work, but tutela decisions also must be given priority over other kinds of cases. Judges have ten days to decide tutelas in the first instance and twenty days in the second, while other legal claims do not come with express time limits. Ordinary judges are the first step in the process of constitutional claim-making through the tutela procedure that eventually leads to the Constitutional Court. If, as shown in Figure 8.1, they are unable or unwilling to keep up with the workload of social constitutionalism – and again, in the Colombian case, that workload is particularly onerous – judicial receptivity to the social constitutionalism at the Constitutional Court and the social construction of legal grievances will not be sufficient to propel a feedback loop and continued claim-making. Citizens may initially make claims and judges may initially be receptive to these claims, but these dynamics may not endure. Whether intentional or not, if judges do not provide the procedural experience (i.e., fair, efficient, etc.) or outcomes that claimants seek, the conditions for continued claim-making could break down.

Figure 8.1 Judicial workload and constitutional embedding.

The rest of this chapter documents the daily work of social constitutionalism, tracking geographic and temporal variation where possible. It also chronicles how judges at different levels of the judiciary understand this work and the difficulties that come with it, before moving to a discussion of the consequences of overwork and underdelivery. The chapter closes by noting how social constitutionalism in Colombia endured despite these work-related challenges.

8.1 Daily Work: What’s Changed?

The 1991 Constitution introduced the new Constitutional Court and the tutela procedure, in the process reshaping the duties of judges throughout the judicial hierarchy. The addition of a new court meant a rearrangement of the judiciary that involved a great deal of tension between the various Colombian high courts (as documented in Chapter 7). For the majority of judges in the country, however, the introduction of the tutela procedure had a much bigger impact. The obligation to offer quick decisions on tutela claims soon came to dominate the daily work of ordinary judges, not just those working in the newly created Constitutional Court.

Every year, the judiciary submits a report to the Congress, which includes a variety of statistics, including the number of judges per 100,000 people, the number of different kinds of claims filed, and even the number of women working in the judiciary. Between 2001 and 2021, these reports noted that there were ten to eleven judges per 100,000 people in Colombia, and at least one judge in every municipality.Footnote 1 For perspective, this ratio is on par with several European countries, including France (11.2), Italy (11.9), Norway (11), Spain (11.2), and Sweden (11.6), according to the 2022 Council of Europe judicial systems report.Footnote 2 Looking within the Latin American region, the number of judges per 100,000 people in Colombia appears to fall squarely within the middle of the spread: Chile has 6.5 at the low end, while Costa Rica sits at the high end with just under twenty-two.Footnote 3

While the number of judges remained relatively consistent over time, the number of legal cases that these judges were asked to process did not. In 1996, Colombians filed 2,676 legal claims per 100,000 people. That number increased to 4,773 by 2021.Footnote 4 This pattern is even more pronounced when we look to tutela claims in particular. There was a slow but steady increase in tutelas from 1992 to 1998, and then the number of claims per year jumps significantly until about 2015. By 2015, Colombians were filing over 600,000 tutela claims each year, in addition to more traditional kinds of legal claims.

What’s more, many who filed tutela claims also filed what are called incidentes de desacato, or contempt orders, when they believed that the decision in their tutela claim had not been complied with. In 2017 – the first year that such a statistic was included in the report to Congress – about 43 percent of the time those who filed tutela claims also filed incidentes de desacato.Footnote 5 The rate of filing incidentes de desacato has remained relatively steady since then (in 2021 it was 41 percentFootnote 6). The 2021 report suggests that “[t]he high filing rate of incidentes de desacato is related to the practice of complying with tutela orders once the contempt claim is in progress, but prior to sanction.”Footnote 7 The filing of incidentes de desacato is particularly common after receiving a positive response to a health tutela claim.

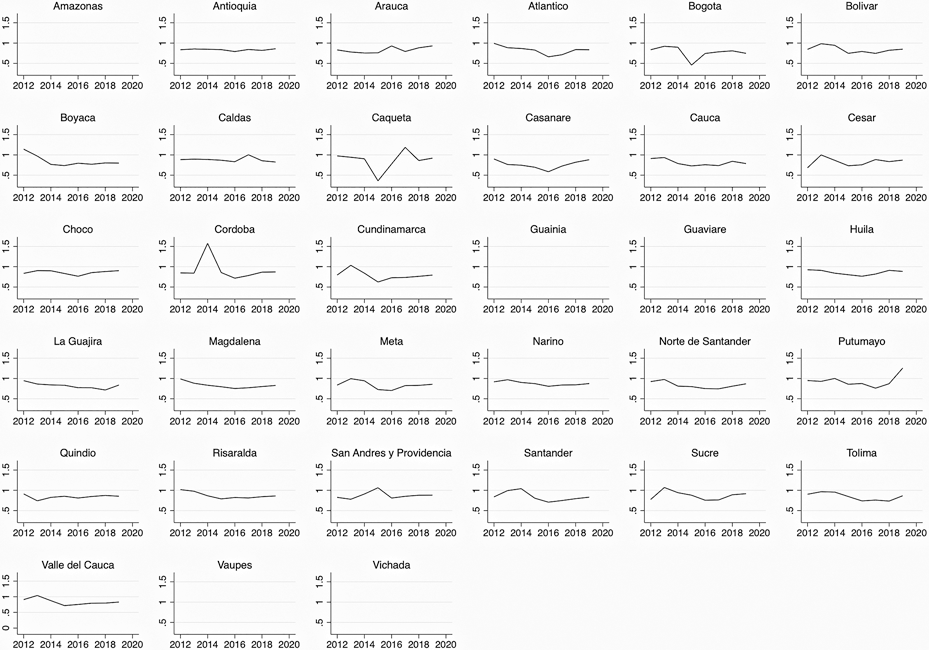

Looking subnationally, we see variation in the number of tutela claims filed. Figure 8.2 shows the monthly average number of tutelas filed per 1,000 people in each department between 2003 and 2019, according to judges in the ordinary jurisdiction (i.e., excluding the specialized jurisdictions).Footnote 8 These data were collected from the judicial statistics reports posted on the Rama Judicial website. While the rate of claims filed is fairly consistent in some departments, in others we see significant periods of growth or even single-year spikes. The mean number of tutelas filed per 1,000 people per month is 7.1. The highest reported monthly average was 40.3 over the course of 2017 in Caquetá. We also see spikes in tutela claims filed in Antioquia in 2015, Bogotá in 2015, and Sucre in 2010. In short, the workload created by tutela claims is not evenly distributed across the country, and it changes over time in ways that are likely challenging for judges to keep up with or adjust to. We might reasonably expect judges to adapt to the increased workload brought about by the tutela procedure when claim-making rates remain relatively consistent over time, and even when rates increase steadily. What Figure 8.2 shows, however, is that, at least in some years in some departments, there are periods of steep – and potentially unexpected – increases.

Figure 8.2 Tutela claims per 1,000 people (monthly average).

It also is clear that claim-making is not simply the product of those living in major cities. While claim-making is prevalent in the departments of Bogotá (home to the country’s largest city, Bogotá) and Antioquia (home to the country’s second-largest city, Medellín), it is certainly not limited to these two departments. After accounting for population, we see increasingly high rates of claim-making in departments like Caldas, Caquetá, Norte de Santander, and Risaralda. Further, eleven departments (of thirty-three) experienced at least one year in which the average monthly rate of tutelas filed per 1,000 people exceeded fifteen: Antioquia (ten times); Caquetá (nine times); Caldas and Putumayo (five times each); Meta, Quindío, and Risaralda (four times each); Norte de Santander and San Andres y Providencia (three times each); Bogotá and Tolima (twice each); and Arauca, Magdalena, and Sucre (once each).

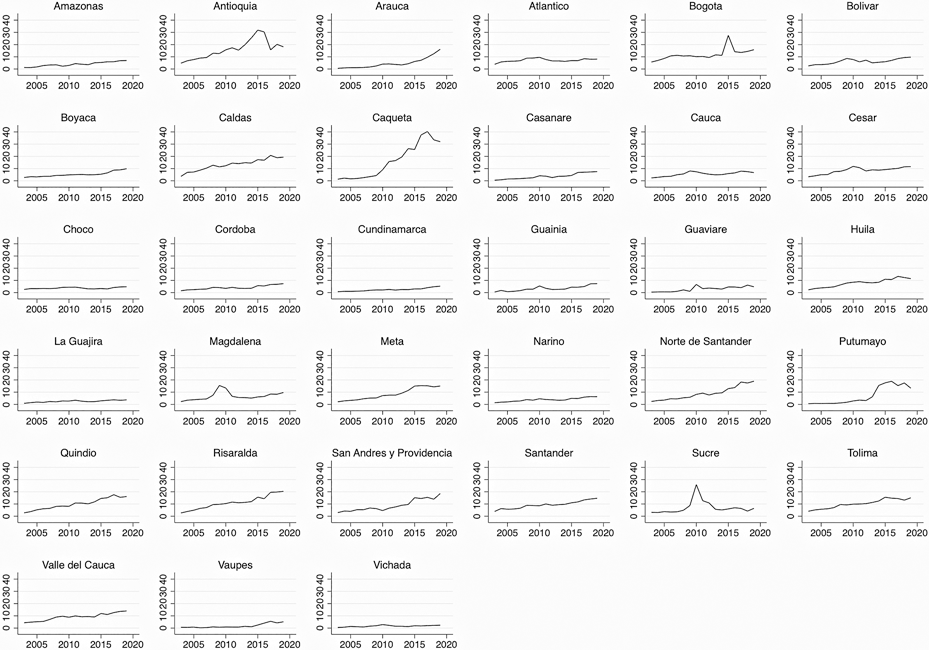

Figure 8.3 standardizes the claims per 1,000 people filed by the number of ordinary courts in each department.Footnote 9 The mean number of tutelas filed per month per ordinary court is 10.5 according to data provided by the judges of the ordinary courts, and 8.7 according to data provided by the Defensoría del Pueblo. The maximum number of tutelas filed per month per ordinary court was thirty-two according to the ordinary judges’ reports, and thirty-four according to the Defensoría del Pueblo reports. Even partially accounting for the differential opportunity to file claims (theoretically, if there are more courts and more judges, one could more easily file claims), there are differences across departments and over time. For instance, we see more than twenty-five tutelas filed per month per ordinary court in just three departments: Antioquia in each year between 2013 and 2016, Caquetá in 2016, and Putumayo in 2015.

Figure 8.3 Tutela claims per ordinary court (monthly average).

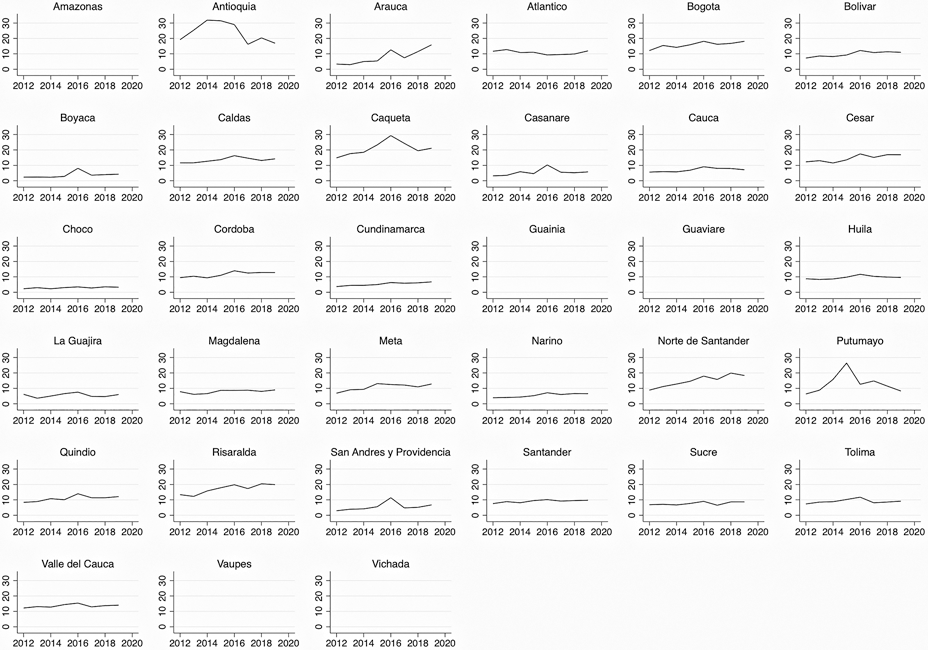

In 2019, the ordinary courts reported an average of 57,854 tutelas coming in each month across the country and 155,154 procesos (legal proceedings for claims other than the tutela). Tutelas, thus, made up about 27 percent of the incoming cases for ordinary judges, up from about 24 percent in 2012 (the earliest year for which data reported by ordinary judges are available). Figure 8.4 shows the rate of legal claims filed (both tutelas and procesos) compared to decided each month in each department, as reported by judges working in the ordinary jurisdiction.Footnote 10 At least for the period of 2012 to 2019, clearance rates do not seem to be getting worse, and in most departments, the rate seems to be consistent. On average, 85 percent of the legal claims coming in were resolved each month, though there is some variation across courts and departments. While disaggregated data on these trends in earlier years are not available, the Superior Council of the Judiciary reports that in 1997, tutelas made up only 3 percent of total incoming cases, compared to 27 percent in 2019, suggesting a major increase in the proportion of judges’ daily work taken up by tutela claims.Footnote 11

Figure 8.4 Proportion of procesos and tutelas cleared (monthly average).

8.2 In Their Own Words: Ordinary Judges on Their Work

Undoubtedly, the introduction of the tutela has created more work for ordinary judges, and that work is not distributed evenly across the country. But to what extent does this extra work pose a problem for judges? I turn now to my interviews with lower-court judges in Medellín and Cali for an additional perspective on how judges outside the Colombia Constitutional Court – ones who are tasked with the initial tutela decision-making – understand this work. Importantly, these views do not necessarily reflect the modal understanding of the tutela procedure among lower-court judges, but they do offer insight into some of the challenges posed by the tutela procedure for judges.

First, the quantity of the work is overwhelming at times. Further, many interviewees noted that lower-court judges have not necessarily studied constitutional law or the specific subjects invoked in tutela claims. This concern came up for many of the criminal law judges I interviewed. For example, Albeiro Marín explained how this workload can come to be all-encompassing. He noted that “tutelas, criminal proceedings, sentences, incidents of contempt, all of this is resolved simultaneously. There are too many tasks at the same time, so another issue appears that seems very important to me is the judicial error, the great possibility of judicial error.”Footnote 12 Cristian Cabezas stressed the gap in knowledge that many judges will have on matters related to tutela claims:

Not all judges are experts in constitutional law … Through the tutela action we can get involved in all the processes that involve fundamental rights. A criminal law judge like me, who knows and has specialized in criminal law, who works every day in criminal law, may be forced to resolve a matter of labor law, civil law, social security, administrative law.Footnote 13

Similarly, Juan Sebastián Tisnés noted the potential costs of this lack of expertise:

The cost is sometimes very serious. I am not necessarily an expert in health, right? So, I think that there should be specialized judges in tutelage but since there are not, and we cannot deny justice, we have to learn [on the job] … There are areas in which you are more comfortable, in my case, for example, criminal law. I prefer to go to those hearings all day than to decide tutela claims, because there I feel like a fish in water. When deciding tutelas, not so much, but because I have to do it, because it is part of my job, I do it.Footnote 14

In addition, Cabezas noted that:

I spend all day processing the criminal cases, and the I must race to process the tutela claims. Many times, I cannot spend the same amount of time on the tutela as I do on the on analysis that I do for the criminal processes. On many occasions, tutelas solutions may not protect rights to the extent that they should, but it precisely has to do with the workload. If we process seven criminal proceedings a day and then all the tutelas sentences, that implies a great load. The tutela has an impact, I would not dare to say negatively, but it has an impact on the workload.Footnote 15

The risk here is that mistakes might occur, or that some judges may choose to cut corners given this crunch. In fact, one person who worked in the Constitutional Court as a law student shared with me her frustration that many incoming tutelas seemed to include passages that had been copied and pasted from previous claims (with the wrong names and facts).Footnote 16

Other judges suggested that the time crunch also worked in the opposite way: responding to so many tutela claims inhibited their ability to devote as much time as they would have liked to the other legal claims they were tasked with adjudicating. One succinctly asserted that the quantity of tutela claims “leads to the neglect of other processes.” While these other claims are not tutelas, “claimants have their right to have their problems solved, because if they come here to seek solutions to problems, it also requires a quick solution.”Footnote 17 Here, the claim is that the extra workload created in tasking judges with deciding both tutela claims and typical legal claims at once puts judges in a difficult position, as they have to decide where to cut corners.

Viviana Bernal, a judge working in the labor courts in Cali, concluded that in order to be a good judge of the tutela, you must be something of an autodidact, “because the tutela actions are so unpredictable, and they require your immediate attention. You do not know what will happen, and you do not know what [kinds of requests] people are going to present to you.”Footnote 18 Carlos Rodríguez, a criminal law judge, concurred, explaining that “you have to review constitutional jurisprudence daily. The Constitutional Court is always giving an interpretation of fundamental rights and how they apply to each specific case.”Footnote 19 In order to avoid making errors, deciding cases incorrectly, and doing a disservice to claimants, ordinary judges across specialties must study constitutional matters.

Another judge commented that one of the most difficult parts of his job was “the drama of the tutela and incidentes de desacato, which do not stop being dramatic – that a person needs a health service and they are denied it.”Footnote 20 He was alluding to the fact that oftentimes, one tutela order is not enough to ensure compliance, even though the medicine or procedure sought might be time-sensitive. Instead, the claimant must seek a contempt order in the hope that the second order or a more severe penalty will prompt compliance. Not only does this impact the claimant, but it also increases the workload of the judges involved.

Andrés López, a judge working in Puerto Tejada, explained in detail some of the challenges that come with contempt orders. For one, the teeth behind the contempt order lie in the ability to arrest someone for noncompliance. However, in order to deprive someone of liberty (i.e., arrest them) in this case, the judge must notify that person directly:

[For example,] I personally must notify a man [whose company is based] in Bogotá and he is never there, so it is useless for me to send the notification to the company’s address, not if he has to be present to receive it … Sometimes the tutela even gets canceled. The Circuit Court cancels tutelas, because they say that I did not notify the implicated person, I did not guarantee the right of defense … because I had to notify them personally there in the entity that there was a tutela. Then there are [other] notification problems because one calls an entity to fax it and everything, to the manager, let’s say in Popayán [a city located about 100 kilometers from where López works], and they say that the fax does not go through, that there is no fax. You have to notify them quickly, and if you send it by official mail and it takes many days, so you would have to resort to sending it by private mail.Footnote 21

From there, you would need to get some kind of assurance that the mail was both delivered and received. Email does not seem to work either, frustrating López even further: “It does not make sense if we are in the twenty-first century and technology is designed to speed up things like this. They give me an email for an entity that provides public services … I don’t care if the person working there saw it and didn’t read it. That’s his problem.”Footnote 22 But, of course, it is López’s problem too, given the rules around notification, and there is no blanket policy that will perfectly balance the protection of the rights of the accused and prevent the manipulation of procedural rules by those who wish to avoid legal sanction. Other judges told me about making phone calls to try to ensure that tutela orders were received and understood, and one even described making regular trips down to the various medical offices to follow up on his orders.

All of this extra work must happen on a judge’s own time, in addition to carrying out their other duties. Some judges may enjoy and have time for this extra work, but others may not, creating another source of inconsistency and inefficiency in the tutela process. As Albeiro Marín, who works in the town of Palmira, explained:

One of the delicate things as a judge is that one is a human being, a human being full of needs, [needing] to be with the family on the weekend, to go out and have a little leisure time, like any normal person. Something complicated happens here, you work from Monday to Friday officially from eight in the morning to five in the afternoon, but you have to take work home at night and on Saturday and Sunday, too. So not only is it the workplace but also the personal sphere that is totally permeated and affected by your job.Footnote 23

This work overload is exacerbated by the particular conditions judges face in their jurisdiction. Marín continued, explaining that no matter how intelligent or diligent a judge is, the workload can be too much:

How is a reasonable amount of work for a judge going to be determined in Colombia? Because it is not possible. A judge in Palmira, for example, which experiences so much crime, receives 1,000 cases, and a judge from Buga, which is a quieter town, can easily have [just] 200 cases, no more, yes? So how do they demand so much of me? So, for example, here we were three judges bearing that extremely high load, all with an average until recently of 800 cases, 400 prisoners, plus tutelas, incidents of contempt, and other series of activities that you also have to be studying.Footnote 24

Not everyone I interviewed faced these kinds of pressures, and some spoke about making tutela decisions as relatively routine, rather than burdensome. What is key here is that at least some judges in some parts of Colombia see the tutela as creating additional work that makes it challenging for them to do their jobs effectively – in deciding matters that fall within their specialty (like criminal or civil matters) and in deciding tutela claims.

Overall, though, the introduction of the tutela presented new challenges to judges as they sought to carry out their daily work. The timing of tutela decisions as well as the subject matter pushed judges to do not only more work than they had previously but also to engage in different legal topics that some of the time might be outside their expertise. To sum up his views on the effects of the tutela procedure, one judge referenced the phrase made famous by the poet Guillermo Valencia during Rafael Uribe Uribe’s funeral – “blessed be democracy, even though it may kill us” – suggesting “blessed be the tutela, even though it may kill us.”Footnote 25 Typically, interviewees – both those working at the Constitutional Court and those working elsewhere in the legal system – evaluated the tutela positively, pointing to the immense advances in access to justice brought about by the mechanism, though many also recommended revisions to the way that tutelas are processed in the hopes of reducing congestion in the legal system. The most common suggestion involved the creation of a specialized set of judges whose only job would be to review and decide tutela cases.

8.3 Overwork, Underdelivery, and the Endurance of Social Constitutionalism

The concern here as it relates to the stability of the constitutional order is twofold. First, if judges are unable or unwilling to keep up with the work of tutela decisions, the tutela and rights claim-making may lose significance in people’s everyday lives. Equally important is the issue that judges cannot compel compliance, even with contempt orders. To the extent that tutela decisions are understood to be insufficient (whether because judges offer the “wrong” remedies or because of noncompliance), unmet expectations may come to undermine social constitutionalism. If people turn away from legal mobilization, from using the tutela, the feedback processes that serve to embed social constitutionalism will falter. However, thus far, these challenges related to work and workload have not overcome the countervailing, embedding forces behind the 1991 Constitution.

In terms of the first concern, it appears that much of the time judges are, in fact, keeping up with the extra work of social constitutionalism. Referring back to Figure 8.4, at least for the last ten years or so, judges have been relatively consistent in terms of the percentage of both tutela claims and procesos they clear each month (despite some variation across departments). We might think that this relative consistency is due to the combination of normative and coercive incentives. Most of the judges I spoke with shared a desire to do a good job and indicated that they viewed their job as an especially important one. Many also reflected that they were constrained by the rules regarding the tutela. Carlos Rodríguez explained that the tutela primarily impacted his work in that, when a tutela claim is filed, “you have to put aside many things you are doing to dedicate yourself to that issue, and the tutela covers any possible issue … it can be pension issues, purely labor issues, social security issues that are very technical, issues related to the right to water, [or] right to public services that are very technical.”Footnote 26 If you failed to do so, you might be subject to serious penalties. Jorge Montes, who worked in a judge’s chambers in Cali, described a similar concern:

What we fear the most is violating the terms of the tutela. That is why the tutela has been effective, because we fear that. So, there is no excuse. I’ll give you an example, when I was an assistant to a judge, I could have four or five tutelas that needed to be decided in one day. It was no excuse to say, “I have five tutelas.” You had to do them. I had to take tutelas home [after my normal workday].Footnote 27

Finalizing the tutela decision late was not an option. Johnny Braulio Romero shared what happens if he submits tutela decisions late (i.e., after more than ten days):

I can be suspended from my position for a month, two months, a year, depending on how serious the offense was. In the case of the tutela, as it is about defending fundamental rights, it is assumed that they cannot wait. I cannot decide [those claims] whenever I want. If there is one thing that the judges respect in Bogotá, Amazona, the coast, wherever, it is the term to resolve a tutela, because being a day late means that they can sanction you, and the sanctions are very severe, and nobody wants that.Footnote 28

While not every judge brought up possible suspension, all noted that the tutela decisions must be made within ten days and that the decisions must be in line with the Constitutional Court’s jurisprudence. It appears that judges have kept up with the work of the tutela, at least well enough. The rules regarding the tutela and the expectations judges have about their work have ensured that judicial receptivity endures.

Further, the interconnections between the tutela, health, and the new constitution seem to have mitigated the second concern about perceptions of judicial work. Many folks continue to view the formal legal system as too slow, as corrupted, or as otherwise ineffective overall, and that does drive some to seek alternatives. As Juan Sebastián Tisnés told me:

When I worked in a small town, someone asked me, “Judge, I have a bill of exchange that Don Carlos owes me, how long does that process take here [if I try to resolve it through the courts]?” So, I told them, “It depends, but it will last eight months or a year.” They said, “yo mejor voy abajo” [literally, I better go downstairs]. To go downstairs is to go to the guerrillas. It is faster there, and I say this without blushing, all the principles established in the civil code, the guerrillas respected, except if you take the case there, they charge you, but otherwise all concentration, speed, everything was carried out … There was coercion because people could lose their lives for not paying the debt … There are things that prevent people from having a good image of us [the judiciary], for example, the time it takes for judicial decisions to be pronounced, the accumulation of cases that then causes the postponement of hearings, the corruption that exists in the judicial branch.Footnote 29

This frustration and disenchantment that citizens express about the formal legal system, however, has not spilled over into the realm of the tutela. Instead, as described in Chapter 4, thinking about the use of the tutela seems to be more ambivalent than anything – folks are not sure it will work, but they might as well try (see also Taylor Reference Taylor2018). The 1991 Constitution has become embedded in people’s understanding of their social worlds, yet that embedding has not come with raised expectations. As a result, expectations have not been undercut or unmet and hopes have not been dashed. So far, ambivalent legal mobilization and its influence on how everyday Colombians and judicial officials understand the 1991 Constitution has been able to counteract the challenges presented by the everyday work of social constitutionalism.