One might well ask: Why are we here, in a village of no particular significance, examining the struggle of a handful of history’s losers? For there is little doubt on this last score … There is little reason to believe that they can materially improve their prospects in the village and every reason to believe they will, in the short run at least, lose out, as have millions […] before them.

The justification for such an enterprise must lie precisely in its banality.Footnote 1

Not everyone benefits equally from the emergence and embedding of social constitutionalism. This chapter examines the promise of Colombian social constitutionalism and those it leaves behind. State efforts to expand access to citizenship goods, whether by the creation of new rights or the extension of existing policy, are often partial and uneven: what happens to those who do not qualify for these goods but believe they should? In other words, what happens to those who are disadvantaged both politically and economically, but are not understood as deserving in legal terms? These challenges – what I call challenges to legal legibility – can undermine the process of constitutional embedding. As shown in previous chapters, citizens have been able to attempt to attain access to healthcare services and compel official responses to information requests by filing tutela claims. They have also been able to file tutela claims to seek benefits offered to those who can document that they were victims of the armed conflict.Footnote 2 Yet, many marginalized citizens are unable to document victim status and instead are viewed as simply “poor,” rather than direct victims, but they nonetheless feel abandoned by the state.

It is precisely “history’s losers” (to use Scott’s term) who the universalizing promise of the constitutional recognition of social citizenship seeks to serve. In the social constitutionalist model, all citizens, regardless of employment status or connections to elites, should be able to gain access to the goods and services necessary to fully participate in political and social life as a matter of constitutional rights. Yet, often the expansion of legal protections, especially as they relate to social service or welfare provision, has both formally and informally involved the construction of notions of the deserving versus the undeserving poor.Footnote 3 The idea is that only those who are particularly deserving – whether because of something they are understood to have done (or not done) or because of something they are understood to be (or not be) – should have access to those protections. Rights, then, become contingent not only on the ability of citizens to make claims to them but also on whether or not claim-makers are understood to be deserving.

When folks understand themselves to be deserving, but formal institutions do not,Footnote 4 that tension can present a challenge for constitutional embedding. In the context of social constitutionalism, there is a promise of significant change, but what is actually delivered might instead be the reification of difference. Further complicating matters is the fact that this kind of reification can occur on some issues, while substantive change is made on other issues – a process than can trigger the growth of an expectations gap and a sense of comparative grievance (Kruks-Wisner 2021) or informed disenchantment (Gallagher Reference Gallagher2006, 2017). The underlying frustration remains the same across mechanisms: the process is not working for me. With respect to comparative grievance, this frustration is directed at a perceived inequality: the process is not working for me, but it is working for other people. With informed disenchantment, on the other hand, the frustration is directed at the disconnect between how the process is promised to work and how it actually does (or does not) work.

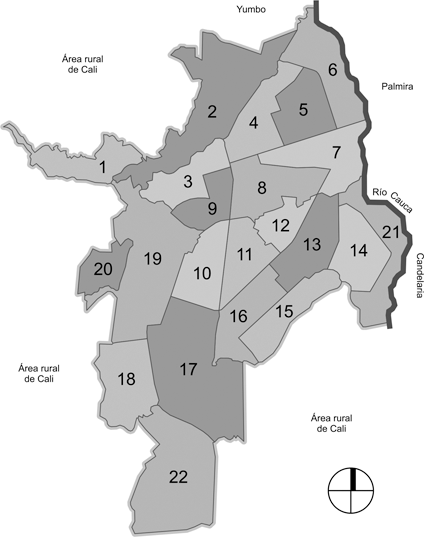

This chapter turns to the meaning of the 1991 Constitution and the tutela procedure in a marginalized neighborhood on the outskirts of Cali, Colombia called Comuna 14. Comuna 14 is located in the district of Agua Blanca, which is comprised of Comunas 13, 14, 15, and 21 (see Figure 6.1). Agua Blanca is home to about 700,000 people. The district is infamous for its poverty and high levels of violence. In April and May of 2017, I conducted twenty-four unstructured individual and group interviews with a total of forty-three people in Agua Blanca.

Figure 6.1 Comunas in Cali, Colombia.

My interviews provide an empirical window into the relationship between law, rights, and social incorporation, and the lived experience of unrealized promises and disillusionment. While this empirical window is particular in many ways – the highly politicized and polarizing 2016 peace agreement had recently been signed, rejected in a contentious popular vote,Footnote 5 renegotiated, and enacted;Footnote 6 the decades-long internal armed conflict was still ongoing in certain parts of the country; the Colombian legal apparatus was uniquely accessible given the tutela procedure – in many other ways it is not. Marginality and dislocation are all too common features of everyday life for people around the world, specifically for citizens who are not treated as such (and for those are who are not recognized as citizens, even on paper). This chapter seeks to build on the robust body of scholarship that examines the limits of liberal legalism in confronting the structural realities of unequal class relations (e.g., McCann and Lovell Reference McCann and Lovell2020).Footnote 7

With respect to the 1991 Constitution and the tutela, there are overlapping sets of concerns. Who does the Constitution actually benefit? What kinds of problems are tractable with the tutela, and what kinds of problems are ill-suited to it? Building from that, are certain kinds of people more likely to have problems that are tractable with the tutela and therefore the new Constitution?

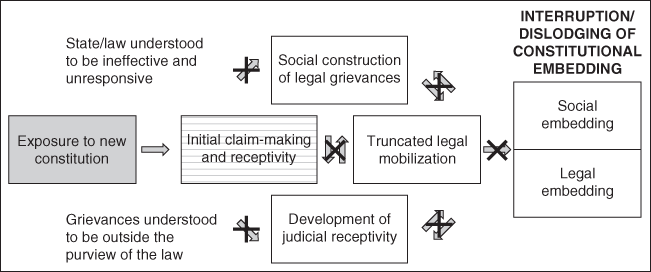

I engage my interviews and observations in Agua Blanca to investigate the politics and lived experience of the relative “have-nots” (Galanter Reference Galanter1974), the marginalized, those whose problems fall outside legal recognition, and the remedies offered by the 1991 Constitution. Paradoxically, the addition of new legal recognitions and protections for citizens may generate a sense of disaffection and leave some with the perception that they are even more vulnerable, as expectations gaps and relative losses grow – which in turn can cut against constitutional embedding. Here, the process of constitutional embedding can be truncated, in terms of both its legal and social components, at least for certain communities (as shown in Figure 6.2). After exposure to the new constitution, if people understand the state and the legal system to be ineffective or unresponsive to their specific needs, and if those needs remain outside the realm of the law according to the legal establishment, the feedback loops that push constitutional embedding will not emerge.

Figure 6.2 The interruption of constitutional embedding by legal illegibility.

In the case of residents of Agua Blanca, however, it is not clear that such an expectations gap ever emerged. If someone never believed in the promises of the state or the new constitution (or never seriously considered those promises as things that could impact their life), then partial rights protections or even the complete absence of rights protections will not trigger pushback. While folks in Agua Blanca were deeply knowledgeable about the tutela and how one can use it to gain access to some healthcare, that knowledge did not readily translate into the language of rights or increased expectations regarding rights fulfillment. In Agua Blanca, the consequences of social constitutionalism seem to be limited to the bureaucratization of rights; to the turning of grand promises into paperwork.Footnote 8 The constitution may not be embedded in this particular community, but the risk to overall embedding in Colombia is limited. Put simply, the very marginality that defines the lives of residents of Agua Blanca also works to confine the limits of constitutional embedding to the margins.

6.1 Interviews in Agua Blanca

Before moving to my investigation of legal legibility and constitutional embedding, a few words on the interview process and the interviewees are in order. A local interlocutor, who I will call Daniela,Footnote 9 connected me with each interviewee and was an active participant in the majority of these interviews. In fact, much of the time we simply walked around the neighborhood and stopped in, chatting with whomever was home, and moving to an official interview if folks were interested and felt comfortable. The interviewees, thus, were part of Daniela’s social network and are not necessarily representative of the district as a whole. Further, the concerns of those in Agua Blanca are not necessarily representative or even indicative of everyone who feels left out of the new constitutional order. These interviews, however, present a unique opportunity to learn something about how one particular group of marginalized folks think about the 1991 Constitution and the problems in their lives. To return to Scott’s justification at the outset of this chapter, my hope is that the unfortunate banality of the situation that folks in Agua Blanca find themselves in will provide “portable insights” into the promises and limitations of constitutional embedding.Footnote 10

All twenty-four interviews took place in or right outside respondents’ homes and more often than not took the form of informal conversations about justice in Agua Blanca or in Colombia more broadly. Frequently, family members, friends, or neighbors of the primary person we were speaking with wandered into the room in which we were conducting the interview. At times, some of them would decide to join in. Most of the people we spoke with noted that they have inconsistent ties to the formal labor market, tending to work informally or on short-term contracts. They also told us stories about interactions with potential employers that faltered as these employers became reluctant or unwilling to hire them after finding out that they live in Agua Blanca.Footnote 11 Violence was ubiquitous. One resident lamented that “here, one buys a gun just like they’re buying a pen. And the police know.”Footnote 12 Further, most of their interactions with the state involved interactions with the police, interactions which often left them and/or their children bruised or even worse off. Another described the police as treating young people in Agua Blanca inhumanely, saying: “They take them and beat them and hit them without any justification, without any reason. They mistreat them, they kick them, they hit them in the face.”Footnote 13 Some interviewees rolled up their sleeves, pulled up their shirts, or scrolled through photos on their phones to reveal bumps, bruises, and scars that they attributed to violent treatment at the hands of the police. In short, these folks understand themselves to be largely excluded from the benefits of both political and economic life, despite the universalizing promises of rights protections under the new constitution.

The interviews primarily focused on folks’ experiences with the formal legal system and particularly the tutela procedure. Though I had not originally intended to discuss the 2016 peace process or the internal armed conflict it was meant to resolve, frustration with the underlying assumptions of this process repeatedly came up. This frustration centered on the ideas that the guerrilleros were being treated differently (i.e., better) than people in the neighborhood and that only certain people were given access to state resources (those who could document “victim” status and those who had been active participants in the conflict), though everyone was affected by the conflict. In what follows, I share findings from these interviews, first in relation to rights, the tutela, and the 1991 Constitution, and then in relation to poverty and the armed conflict.

6.2 Constitutional Law in Agua Blanca

As documented in previous chapters, with the introduction of the 1991 Constitution, its expansive set of rights recognitions, and the tutela procedure, Colombians were able to make claims about potential rights violations relatively easily. However, this ability on paper doesn’t mean that folks viewed the problems in their lives as legal in nature or thought that they could advance their own claims through the courts. Problems are not innately “legal,” and problems that could be resolved through the legal system are not always viewed as such.Footnote 14 William Felstiner, Richard Abel, and Austin Sarat (Reference Felstiner, Abel and Sarat1980) and Richard Miller and Austin Sarat (Reference Miller and Sarat1980) lay out this situation in the form of the “dispute pyramid”, with “unperceived injurious experiences” at the base and formal legal disputes at the peak. As documented in Chapters 4 and 5, the process of legal recognition – or of moving from an unperceived injurious experience to a legal claim that might be accepted – is interactive and iterative, involving the social construction of legal grievances, or how problems come to be understood as legal grievances, and the development of judicial receptivity, or how judges come to understand problems as properly resolved in the formal legal sphere. While repeated legal claim-making has broadly led to the right to health becoming legally legible to everyday citizens and judges alike in Colombia, that legibility falters when we look to Agua Blanca and Comuna 14, where poverty, discrimination, and bureaucratic rules complicate access to healthcare services.

The accessibility and perceived necessity of the use of the tutela are core features that facilitated the social embedding of the 1991 Constitution, particularly as the tutela related to health. The connection between the tutela and access to healthcare are just as strong in Agua Blanca as elsewhere in the country. Almost everyone spoke of the tutela only in reference to health claims. As is the case throughout Colombia, perceptions of the tutela are often imbued with a sense of ambivalence: filing a claim may or may not work; it has helped some people, but not everyone; you can’t count on it. As Verónica, a nurse, explained:

My opinion on the tutela? It has benefited many people for treatments and surgeries, yes. In other words, the tutela has helped a lot for high-cost treatments or high-cost medications. Many people have benefited, right? But there are other people who haven’t. People who haven’t have to go to the media, to the radio, to television to get their problem resolved.Footnote 15

On the topic of healthcare specifically, she noted:

In Colombia, healthcare is very poor and is getting worse … Medications are bad, treatments are bad. You have to file tutela claims, you have to be suing, you have to be harassing them to give you a good medicine. [Without the tutela] all they give you is acetaminophen, ibuprofen, naproxen, blood pressure pills, and nothing more. That is what matters to them [the tutela claim]. The rest [of patients], they die.Footnote 16

Teresa, who I referenced at the start of this book and who lived down the road, shared a story with me that echoed Verónica’s. She told me about a time when she had trouble breathing. She did not have formal employment and could not afford private medical treatment. Facing this barrier in access to healthcare, she filed a tutela claim. And she won. However, the decision required the subsidized health insurance regime to provide her with creams and diapers. The remedy was wholly detached from the problem: what good would diapers and creams do for a breathing problem?Footnote 17 Not everyone fared even this well. Mari shared that she had been encouraged to file a tutela claim by the clinic where her mother was seeking treatment. She explained:

I filed a tutela claim, because my mother had spent a lot of time in a clinic. The clinic was bankrupt and didn’t take care of my mother. She died fifteen days later … My mom died because of negligence … I filed the tutela, but the clinic never did anything.Footnote 18

These experiences, however, did not dissuade Mari or Teresa from asserting that they would use the tutela again.Footnote 19

The folks I spoke with viewed this a compound issue, inextricably linked with poverty. Not only has the tutela become the effective entry point for healthcare services, and not only do healthcare service providers encourage the filing of tutela claims before potentially offering services (things that in themselves draw out the process of gaining access to health). What’s more, those with less must use the subsidized healthcare system (because they do not have the ability to pay for private medical services), and the subsidized healthcare system is staffed by less qualified and less invested people. This last statement is not one that I verified, but its accuracy is less important than the fact that folks shared it with me; that folks believed it.

Laura similarly pointed to the connection between poverty and health when sharing the difficulties her daughter faced in even getting an appointment scheduled:

The public healthcare providers here don’t attend to people. They don’t give them medicine. It’s a problem for them to give one an appointment. Just look at the case of my daughter. It took a year and a half to get her a rheumatology appointment and she needs it. She suffers from rheumatoid arthritis. Look, a year and a half to make an appointment?Footnote 20

Her neighbor, Leonor, saw things the same way. When I asked how she felt broadly about the healthcare system, she explained that “it has improved a little bit, but it is still a 50 out of 100 – and that is for the upper class. Poor folks die sitting in a chair waiting for the doctor to see them.”Footnote 21 Part of this perspective comes from an experience she had just days before we spoke: “I was at the clinic on Thursday. It was an emergency. My husband had pain for over a month, and we went to the doctor. [They just said,] ‘Take this Amoxicillin.’” He wasn’t getting better, so they returned to the clinic, where they were told he would be an “urgent priority.” However, he wasn’t. In Leonor’s words:

We went back on Friday and they operated on him yesterday [Saturday] at dawn. When we were in the surgery room, the surgeon told me, “I went down more than four times to look for your husband. I’ve been here since five in the morning and they said he wasn’t here.” But he had been sitting in a chair for two nights. Why? Because nurses don’t focus on the priority [patients], but rather on other things. Doctors and everyone have become indolent.Footnote 22

This kind of experience was not unique to Laura’s daughter or Leonor and her husband.

Another neighbor, Claudia, had also recently been faced with the limitations on the healthcare services available to residents of Agua Blanca. She told me:

Look yesterday night, [I went to one of the public hospitals]. My niece fell from a second-floor window, through the glass. She landed on some rocks, so they took her to the medical clinic and do you know what they said? That they couldn’t take care of her because they didn’t take care of minors, [not even] a girl who was wounded and her head broken open. They did nothing for her. They sent her to another hospital, another clinic and they did not treat her [there either], because she did not have money to pay the clinic. Her health insurance card did not work there.

So, they had to take her to Carlos Holmes [a medical center].Footnote 23 In Carlos Holmes, they had her there and they didn’t want to attend to her. A police officer she knew from childhood had to call for the girl to be attended to, because the girl’s body was all wounded and they hadn’t treated her yet. She was dripping blood, and she was unconscious for more than half an hour, and they didn’t treat her. That’s when they came to treat her and then there was no ambulance to take her, they didn’t know if they could take her to the hospital. [The health insurance company] had not given authorization.

When a girl falls from a second floor, it is something serious!Footnote 24

Forgetting that the situation had not been resolved, I asked, “and what happened in the end, is she okay?” Claudia responded, “already this morning, they sent her to the public hospital, to do an exam. We are waiting to see the result of the exam.”Footnote 25 She quickly transitioned back to her frustrations with the healthcare system:

Of course, they must treat you whether you have money or not, or whatever insurance card you have. It’s an emergency! What if she’s a baby? What then? Not here. They leave you to die … [and] it’s worse in these neighborhoods [the Comunas of Agua Blanca]. One must run from side to side [of the district]. For example, the insurance card we have is good for Carlos Holmes, but we are closer to López [a different medical center]. If we have an emergency and go to López, which is closer, because if I wait for Carlos Holmes, the patient might die, but [at López] they tell you, “No, no, I can’t attend to him because we don’t take the insurance card.” What is that? This world is turned upside down.Footnote 26

This difficulty in gaining access is not something that the tutela procedure can readily remedy. Claudia’s niece could not file a legal claim and wait ten days for a decision. She needed immediate medical attention. Further, filing a claim does not mean that one will receive a positive or useful response. As Daniela told me: “Yes, we file tutela claims, but they don’t care. They put our demands aside, because we are poor people with little means … They dismiss the demands.”Footnote 27 The value of the tutela – however limited it might be – appears to be limited to the realm of health for folks in Agua Blanca, and the economic conditions of their lives overshadow that value.

After hearing these specific stories of loss and deprivation and the inadequacy of the tutela to address the harms in their lives, I asked if the 1991 Constitution had changed anything in their lives. The answer was a resounding no; that constitutional law felt far away, outside of everyday life. Paula, a woman who survived cancer and whose husband had to threaten to use the tutela to ensure that the insurance company cover the requisite care, told me: “No, I don’t pay attention to such things.”Footnote 28 Laura, who, in addition to trying to help her daughter navigate the healthcare system and attain care for her rheumatoid arthritis, also ran a community organization and had faced multiple threats to her life, explained: “To me it seems like there is a great distance between the Constitution and life. It’s one thing that the Constitution says and another thing that what they do … And rights always go. Rights are violated every day, violated every day.”Footnote 29 For the family of Kike, a young man who had recently been beaten to death, the question did not seem to make sense at all. Daniela stepped in and reiterated my question: “What has the Constitution changed?” Again, the question was met with silence. Eventually, Kike’s mother asked: “What’s that?” I tried to explain: “The new constitution was a huge change in law, but … It is one of the most progressive in the world, but [what about] in everyday life?”Footnote 30 After another pause Daniela answered, “[yet,] we’re dying more every day.”Footnote 31 The others in the room murmured in agreement.

Thus, the everyday problems faced by folks in Agua Blanca do not appear to be ones that can be addressed by the 1991 Constitution, at least not in the view of residents of the district. The issue here is not simply the absence of rights consciousness or a lack of information. Residents of Agua Blanca have a great deal of knowledge on how one uses the tutela, and they have strongly held and often well-informed views on Colombian politics, especially related to the conflict, as Section 6.3 describes. Here, we see the emergence of “informed disenchantment” that results not from experiencing the legal claim-making process and losing faith in it, but instead from having a good deal of knowledge about that process but feeling excluded.

6.3 Poverty and the Conflict

But what can these everyday problems be attributed to, and how might they be resolved? Should they be legally legible? According to folks living in Agua Blanca, the disconnect between poverty and formally recognized experiences of suffering due to the armed conflict account for these problems – problems that have become both intractable and part and parcel of the government’s approach to people like them. They see the new constitutional infrastructure as not offering them much of anything.

Before moving further, a note on the armed conflict and the legal recognition of victimhood in Colombia is needed. Article 3 of the Victims and Land Restitution Law (or Law 1448) of 2011 defines victims as “those persons who individually or collectively have suffered damage from events occurring from January 1, 1985, as a result of violations of international humanitarian law or serious and flagrant violations of international standards of human rights that occurred because of the armed conflict.” Folks who wish to be identified as “victims” must initiate the process of recognition by contacting a Victims’ Unit office in person, by mail, or over the phone.Footnote 32 They must present personal identification, two witness statements, and a description of the victimization and when it occurred. A representative of the Victims’ Unit then attempts to verify the information in the application with the Red Nacional de Información (National Information Network).Footnote 33 Each application should receive a response indicating whether or not they qualify within 120 days.Footnote 34

From the perspective of everyday Colombians, there are tensions within the program as to who qualifies as a victim and what qualified as victimization. So-called “ordinary crimes” do not apply, though it can be challenging to differentiate ordinary crimes from conflict-related crimes given the diffuse nature of the conflict. Further, not all victims – even those recognized under the law – are treated the same. As Paula Martínez Cortés (Reference Martínez Cortés2013: 13–14) explains:

The victims of forced displacement and human rights abuses committed before 1985 may only benefit from symbolic reparations, and not from land restitution or economic compensation.

The victims of human rights abuses committed between 1985 and 1991 have the right to receive economic compensation but not land restitution.

Victims whose lands were unlawfully taken or occupied through human rights abuses after 1991, but before the expiration of the law, have the right to land restitution …

Illegal armed actors who have suffered human rights violations or infringements of international humanitarian law cannot be acknowledged as victims …

In cases of illegal killings committed by the state security forces, which usually claim that the victims belonged to an illegal armed group, relatives are only recognized as victims if a criminal investigation confirms that the deceased person was not part of one of those organizations. Given the difficulties in clarifying such membership, it may be impossible for relatives to obtain compensation.

Elsa Voytas and Benjamin Chrisman (forthcoming) show that in areas where violence was carried out more frequently by state-affiliated actors victim registration is lower than in areas associated with violence by nonstate actors. This may be because those negatively impacted by the state are less likely to turn to the state for redress or it could signal intentional or unintentional exclusion by the Victims’ Unit. Frequently, folks – whether they are recognized as victims or not – report disillusionment and negative evaluations of the registration process (Pham et al. Reference Pham, Vinck, Marchesi, Johnson, Dixon and Sikkink2016; Cronin-Furman and Krystalli Reference Cronin-Furman and Krystalli2021).

Victim status is not legible or tractable outside of this particular social-political-historical moment. While there are precise laws defining who does and does not count as a victim in Colombia, the category of victim is not like the category of refugee. One can be a refugee for a variety of general reasons in different times and different places. Not so for officially designated “victims.” Further, the remedy offered is broad, moving beyond truth and accountability to also address the conditions of daily life and the ability to live well or make choices about how to live: the goal is the realization of constitutional rights.Footnote 35 There are many reasons that one might find oneself in this position of constraint, poverty, and desperation, yet victim status is treated differently. While Law 1448 sets out a clear dividing line between who is and is not a victim, social understandings of victimhood do not necessarily align with the formal legal definition, especially considering the diffuse nature of the conflict and people’s perceptions about what actually happened, who was at fault, and who suffered harm. Further, do those who find themselves in suboptimal life circumstances for other (structural) reasons not deserve protection? And what about those who cannot, for whatever reason, document the devastation that the conflict imparted on their lives? Or those who were negatively impacted by the conflict before 1985?

These questions are ones that many of the residents of Agua Blanca implied in their conversations with me. To be clear, the complaint is not that the government should not support victims of the armed conflict, but that those who fought against the state seem to be getting state support, while not all those who suffered from the conflict do. Further, poverty is understood to be connected to the displacement caused by the armed conflict; yet, poverty is seemingly not legible to the law – certainly not in the perspective of many people from Agua Blanca.Footnote 36

Leonor shared that although her family had experienced violence and displacement, and although her mother had participated in the peace process (including an attempt to claim victim status), her family had not received any benefits, or even an official response, from the state. She described that experience as follows:

Well, you see, I lived through violence for a long time, from a very young age. We were displaced from our farm. We arrived here in Cali, and a brother of mine was taken by the guerrillas when he was thirteen years old. The guerrillas killed him because he was going to run. My mother went, she spoke with them, and we are participating in the peace process now, but it has not worked. They have not yet given us an answer.Footnote 37

She concluded by telling me that justice did not exist for the poor in Colombia. Many others suggested something similar: “Justice is for those who have money; that is, there is the law of money.”Footnote 38 Now, it’s possible that Leonor’s family does not meet the criteria outlined in Law 1448, and it’s also possible that they do but the process simply has not been completed yet. Leonor’s understanding, however, was that her family was being unjustly excluded, despite their deservingness.

For some, this sense that justice was not for the people of Agua Blanca stemmed from unequal punishments for violations of the law. As Verónica explained, “nowadays if you steal a cell phone, they put you in jail, they punish you. If you kill a person, they sentence you to two, three years. And in a year, you get out … This is not justice.”Footnote 39 Paula held that this inequity in punishment went even further:

If a boy is caught stealing or something, they send him to jail, to die in the yard, but those white-collar criminals, who don’t just steal cheese or milk or cell phones, who [instead] steal to buy 200 cell phones, millions of pesos, they steal from the state, they give [the white-collar criminals] a house as a jail or they assign them a room in with a television, a refrigerator, that is, an apartment in a jail and there they take care of them and send them the newspaper.Footnote 40

Laura also shared that she believed that “prisons should be educational centers, centers of reform, but here that doesn’t exist. The young men come out worse.”Footnote 41 What then happens is that young people turn to committing more and more serious crimes.

The perception is that poverty – and thus delinquency – stems from government inattention and neglect, as well as the conflict. Laura explained: “No, I do not trust these people [the government] because they have defrauded us. And the problem here is that, due to poverty, no, it is true, that there are many people who sell themselves for a plate of food.”Footnote 42 Part of the challenge is the connection between poverty and the conflict, or poverty and displacement. Gloria lamented:

People arrive [in Cali] without an opportunity. It’s overcrowded … We are going to have more crime, because as long as there is no opportunity, as long as there is no respect. They are moving from their land, where people have their food, have their lives made and they come here to face a life that is the most horrible thing that can happen to them. I say the most horrible, because I count myself as displaced.Footnote 43

She then told her story of displacement: “We left our land that had everything, where we lived well, to suffer here in the city. To the people here, we are an annoyance.” While the river near where she used to live provided fish after fish, in the city “you have to buy some little fish heads and they have to share them with up to thirty people.” As long as that is that case, “then crime will continue … look, as long as Cali is hungry, there cannot be peace.”Footnote 44

For others, the issue was more that the government appeared to be focused on helping the guerillas instead of investing in noncombatants, in those negatively impacted by the conflict, those understood by residents of Agua Blanca to be rightfully deserving. Diana held that “if you are from the guerrillas, the president … gives you a house. Yes, for the guerrillas. But for us, the poor, no.”Footnote 45 Francia explained:

Those people were murderers, the FARC, and they are not going to pay, they are not going to pay anything! The guerrillas are going to earn more than a worker, an employee who is earning a minimum wage. The minimum wage is 700 and something pesos. And do you know how much each member of the FARC is going to earn? 1,800 for sitting around doing nothing! And where does this come from? Our money, from the people!Footnote 46

Verónica agreed:

The current [Santos] government has focused on what? On peace, peace, peace, and everything is in the doldrums in Colombia. Colombia is a horrible country now, because there is no government. The government we have is all bad, and the mayors are the same. They always favor the upper or middle classes. The poor are not favored at all.Footnote 47

Claudia brought up something similar in a separate interview: “What the government did was, what they did was screw us. [President Juan Manuel] Santos screwed us. This story of peace. Peace screwed us. It’s peace for him, not for us. All he wants is to win the Nobel Prize.”Footnote 48 Daniela chimed in: “He won the Nobel Prize for knowing how to rob the poor.”Footnote 49 I then asked Claudia what peace would mean for her. She replied, “peace for me is equality of all, that is peace. Santos does not want equality for us. What he does have is a preference for the guerrillas, because what he is giving them is being taken away from us poor people.”Footnote 50 Here, she was referring to the increase in the value added tax from 16 percent to 19 percent that the Colombian Congress had approved a few months before we spoke, in December 2016.

6.4 What Does This Mean for Constitutional Embedding?

This chapter has detailed the perception that rights serve some and not others, that there is unfair discrimination built into institutions meant to guarantee universal protections. Ultimately, these perceptions serve as a challenge to constitutional embedding, though perhaps more at a theoretical level. Julieta Lemaitre – who went on to serve as a justice in the Special Jurisdiction for Peace – offers a vision of a state defined by the inversion of the phrase often attributed to Getulio Vargas, “for my friends, anything; for my enemies, the law.” By contrast, Lemaitre envisions a state constrained by the law, a state that offers everyone the benefits and protections of the law. This kind of state would be:

[A] state capable of being a “friend” of the people whom it has historically abandoned. It is not with roads and buildings, nor with the army, that the state successfully expands. It is when ordinary officials echo the values of reconstruction from below, and offer the care and security provided by the best community leaders, not by shadowy powers, that the state successfully expands, that it manages to delegitimize its rivals, and regulate social relations within the law, rather than outside it. Doing this, and doing it openly, within the law, learning from mistakes and successes, is the correct way to expand the Colombian state and make a good life possible for all, the “life loved by all.” Only with such a state can we one day offer the law to our friends as well.

This beautiful vision seemingly remains quite far in the distance for those in Agua Blanca. Near the end of my stay in Cali, Daniela told me, “si la justicia fuera justicia, este país sería muy diferente.” This is to say that law, rights, justice, and citizenship in practice – perhaps especially for residents of Comuna 14 – do not live up to their promises, a reality that has been documented across contexts (e.g., Scheingold Reference Scheingold1974; Thompson Reference Thompson1975; McCann Reference McCann1994). To imagine a Colombia in which law on paper matches law in practice means imagining a very different Colombia.

The 1991 Constitution is less embedded in Agua Blanca than elsewhere in Colombia, and this limited embedding and limited legibility signals a weakness in social constitutionalism, that it is not living up to its grandest of promises. To be fair, if perfection is the standard, any intervention will surely fail, and other forms of political engagement have not sufficiently served this population either. As Francia put it, “we poor people have neither a voice nor a vote in this country. Here we only have a voice and a vote when politicians come to neighborhoods to ask for votes, for us to vote for them … [But then] they forgot about the people, so nothing really happens here.”Footnote 52 Some of the time, folks can mobilize and create poor people’s movements and solidarity-based community organizations, even in the absence of formal or at least regular employment that might form the foundation for union-informed modes of collective action (e.g., Piven and Cloward Reference Piven and Cloward1977). Claudia, Daniela, Gloria, and Laura, in fact, were active participants in these kinds of organizations. My goal here is not to try to weigh the relative benefits of different forms of political participation against one another, but to note that folks in Agua Blanca appear to have relatively few options when it comes to gaining access to state (or alternative) goods and services.

Even if the 1991 Constitution and the tutela procedure only result in access to some medications and long-delayed medical appointments, that’s better than nothing – especially compared to previous levels of access and possibilities to contest the nondelivery of medical services. That said, the new constitutional infrastructure is not understood to address the primary burdens faced by residents of Agua Blanca, especially those harms that we might call “diffusely economic” in nature, including poverty (as compared to stolen wages, for example).Footnote 53 If the goal is to fully realize rights, this disconnect is significant. If the focus is on overall constitutional embedding in Colombia, however, it is not. The limitations of constitutional embedding in Agua Blanca have not prompted a new expectations gapFootnote 54 and have not destabilized the aggregate, country-level processes (namely, legal mobilization through the social construction of legal grievances and development of judicial receptivity to particular kinds of claims) that serve to embed social constitutionalism in Colombia. Considering, however, that the National Center for History Memory (2013) estimates that 17 percent of Colombians directly experienced violence of some kind during the armed conflict, legal legibility or illegibility will likely remain a challenge for constitutional embedding moving forward.