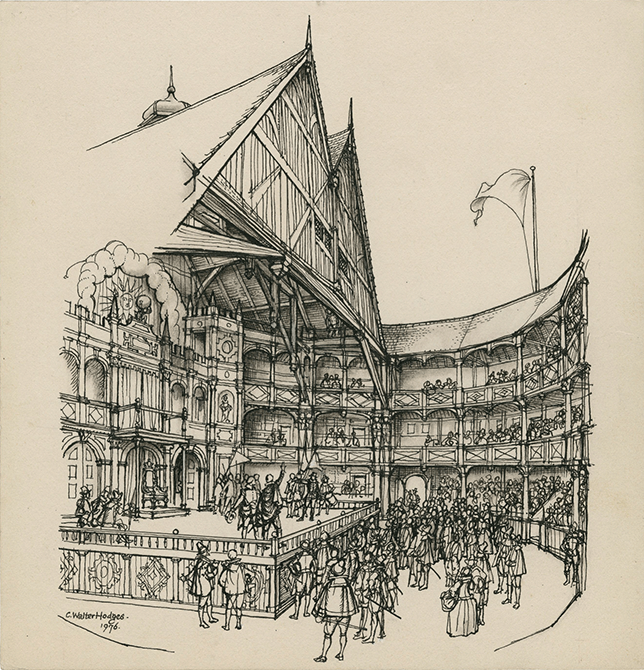

It would be ideal if history had gifted us an accurate picture of what each of these spaces was like. Sadly, that couldn’t be further from the case: we have no complete picture of any of the London playing spaces from the period, and much of what we (think we) know of the Globe and the Blackfriars can only been inferred from evidence relating to other playing spaces. Reconstructing these spaces requires piecing together fragments: chiefly, the architectural foundations of the Rose, Curtain, and Theatre playhouses, along with a tiny portion of the Globe, and a copy of a Dutch tourist’s sketch of the Swan playhouse’s interior. To these we can add a number of other pieces of ‘evidence’ – artists’ impressions of London as a whole, passing references in literary and other documents, and surviving building contracts – but these often make the picture more, rather than less, complicated.

Figure 2.1 The interior of the second Globe playhouse (built 1614) as imagined by C. Walter Hodges.

To make matters worse, each of these scraps of evidence offers something or other to contradict at least one of the others. What’s more, new archival and architectural evidence is emerging all the time – particularly since the turn of the twenty-first century – which sheds new light upon, but more often challenges, the ‘factual’ picture of the early modern playhouses. Envisaging ‘Shakespeare’s Stages’, then, requires a fair amount of educated guesswork, as well as a continuing willingness to revise our sense of what we ‘know’ about the spaces in which his plays came to life.