Introduction

It is well established that people suffering from a mental disorder have poorer physical health outcomes, including increased mortality, than those without such a disorder (1). In addition, people with severe mental illness are more likely to be admitted to non-psychiatric medical services, have longer admissions and present with more emergencies (Reference Ronaldson, Elton and Jayakumar2). The mental health consultation-liaison (CL) team is perfectly placed to ensure holistic assessment and integrated care of this population, with the opportunity to improve both physical and mental health outcomes. There is evidence that mental health CL teams improve a number of outcomes, including decreased mortality and readmission rate and increased patient satisfaction and quality of life (3), in addition to the potential economic benefits of reducing unnecessary admissions and reduced length of stay (Reference Parsonage, Fossey and Tutty4). By offering consultation, the CL practitioner has the advantage of taking a holistic view of a person, plus adequate time to establish a person’s priorities and any barriers to accessing the best care. The roles of the CL practitioner are many but centre around the concepts of patient advocacy, communication with acute colleagues, flexibility and holistic assessments. This chapter aims to outline the practicalities of performing an assessment from start to finish, maximising integration and contribution to positive patient outcomes.

Assessment Overview

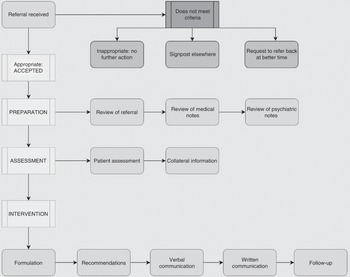

It is important to note that CL practitioners cover a range of areas in the hospital. The assessment process is tailored to the environment, but this chapter is focused on an assessment on the general wards. The principles can easily be translated to any CL assessment. The full process is summarised in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Summary of the mental health consultation-liaison assessment process.

Preparation: Processing Referrals

Does It Meet Our Referral Criteria?

The assessment begins at the point of the referral. Different teams have different approaches to triaging referrals (Reference Imison and Naylor5) and to handover requirements (6). Many organisations will accept and assess all referrals. The benefit of this approach is that it does not expect non-experts to ask pertinent questions, much like it might be unfair to expect a psychiatrist to know how to triage the urgency of a new heart murmur. Behind every referral there is a concern for patient welfare, so value can usually be added to a patient’s experience by routine assessment of all referrals. Some teams apply triage criteria before deciding whether to see a referral. The commonest are:

a. Severity: Some services do have a triage function and do not routinely see all referrals themselves, instead signposting to other services such as primary care, psychology services or substance misuse services. The Royal College of Psychiatrists suggests that CL services have a role in accepting all referrals that indicate a mental health problem which is moderate to severe and/or impairing physical healthcare (7). In theory, there are many referrals which will not meet this threshold and the standard operating procedure of the service may dictate that these cases are best dealt with elsewhere.

b. Age: Different services cater to different populations. Some CL services are ‘ageless’, providing care all the way from children and adolescents to older adults. Other areas have specific older adult and general adult teams, and many areas have entirely different services for under 16s. This will depend on the specific services which are commissioned in individual healthcare providers. If age is a part of the referral criteria, it is important to first check that the patient is with the right team. Flexibility may be required to ensure the patient is seen by the practitioners with the skillset most appropriate for their needs; for example, a 55-year-old patient with early onset dementia may be better cared for by an older adult team (7).

c. Are they ‘medically fit’?: Another part of the referral criteria, which differs between teams, is at which point in the journey the patient is accepted as suitable to be assessed. There has been a tradition that patients are not assessed until they are ‘medically fit’ and some teams still use this model. There are certain circumstances in which it may be appropriate to defer assessment for medical reasons, for example if a patient is too unwell to engage or is acutely intoxicated. Sometimes patients can experience significant changes during their admission, for example when receiving bad news or undergoing significant procedures, which clearly cause fluctuations in their mental state. For these reasons some teams choose to wait until the patient is ‘medically fit’, which will minimise the variability in the patient’s presentation secondary to external factors such as their current illness.

However, there is a strong argument for parallel assessment. Firstly, being in hospital can be very challenging. Patients are away from their families and routine, usually suffering with some sort of pain or discomfort, facing uncertainty and being told distressing news with potentially life-changing consequences. While all staff have a duty to listen and be empathetic, mental health professionals can have an invaluable role in offering psychological and emotional support and getting to the heart of the patient’s priorities. This sort of support cannot be delivered if patients are only seen at the point of discharge. Assessing patients from the start of their admission, alongside the medical teams, also ensures that appropriate planning can take place that prevents delays to the patient journey. It gives an opportunity to ensure thorough assessments without the pressure of an imminent discharge. Very importantly, it fosters positive working relationships with colleagues in the acute wards, and a desire for more parallel working is often stated by acute staff (Reference Becker, Saunders, Hardy and Pilling8).

Encouraging Helpful Referral Requests

Although there are no specific data for CL services, the literature regarding primary care physician referrals to various specialties demonstrates that there is inadequate information ‘fairly often’ or ‘very often’ (Reference Imison and Naylor5), missing key areas such as those detailed in the next paragraph. These referrals can take time away from more pressing needs and sometimes subject patients to a psychiatric assessment which is not needed and not asked for by the patient. Identifying trends in the referral structure creates a shared platform for clarifying what information is helpful to the team and how it can be embedded routinely in referrals.

There is often very little or missing clinical information; insufficient preliminary assessment with no working diagnosis or impression; limited understanding of the purpose of the referral (what is the question being asked?); and the desired outcome of the assessment is unclear (how can the mental health CL team help?).

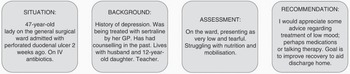

The CL team’s aims and expectations can be advertised through regular educational events and training sessions. In addition, publication of the roles and remit of the team, as well as expected referral criteria, can be advertised on hospital electronic systems and team policy documents or included on the referral form itself. The principles of SBAR (situation, background, assessment, recommendations) can be used to make a robust referral to any specialty team (6). An example of using SBAR is demonstrated in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2 Example of referral using SBAR (situation, background, assessment, recommendations).

Organisational Aspects of the Referral; Prioritising and Allocating

Once the referral has been accepted, there are some pieces of information which help to triage its priority and plan the assessment. Firstly, we need to know where the referral is coming from. Most referrals will come either from the wards or from the emergency department (ED). Assessments for patients in the ED need to be started within 1 hour from the point of referral and within 24 hours for ward referrals (7). There will occasionally be urgent referrals from the wards which require a prompter response, for example a patient with mental illness and risks to self who is asking to self-discharge.

It is also important to know who is referring the patient. This not only helps on a practical level to ensure good communication and feedback after the assessment but also gives some important information which may help to anticipate the priorities of the referral. This will help to allocate the assessment to the appropriate practitioner if available. For example, a referral from a social worker requesting support with discharge planning may be best taken by a mental health social worker, whereas a consultant geriatrician may ask for medication advice which is best given to a doctor or a non-medical prescriber.

Alternative Sources of Referrals

There are occasionally referrals from other sources. Sometimes referrals come from the outpatient clinic, for example when a patient incidentally presents with unusual behaviour or expresses suicidal ideation when attending for a routine medical appointment. In this circumstance, different organisations will have different protocols, but they usually involve the CL team arranging to see the patient either in a designated room in the outpatient clinic or in the ED. If the patient is reluctant to attend the ED or speak with a member of the CL team, the mental health practitioner may have to support the staff in the outpatient clinic to risk-assess the situation and make appropriate onward plans, for example asking the primary care physician to monitor the patient’s mental state or to assess whether a more urgent intervention is required.

Similar phone calls may be received from other agencies outside of the hospital. In some services the mental health hotline, crisis team or single point of access may manage these calls, but in other healthcare providers the CL team may be required to provide advice. Paramedics may call expressing concerns about a patient who is refusing to come to hospital for assessment. The role of the CL practitioner would be to support the referring clinician in risk-assessing and assessing the patient’s capacity to refuse to come for assessment. Primary care physicians may also call for advice. The role of the CL team is to support assessment of urgency and to signpost to the relevant team for further assessment, whether this is a recommendation to attend the ED, make a referral to the crisis team, speak to the on-call psychiatrist for out-of-hours medication advice or make a routine referral to community services, among other options.

The police are another agency that have very frequent contact with the CL team. They may simply be calling for collateral information or may be bringing a patient for a mental health assessment either voluntarily or under a police holding power (Section 136 in England). If the police are bringing a patient under a Section 136, it is important to establish several things. Firstly, what is going to happen if the patient is not deemed to need mental health admission? Can they be discharged or do they need to go back to police custody? Are they under the influence of any substances or alcohol? If they are intoxicated and at risk of withdrawals, the patient needs to attend the ED rather than a Section 136 Suite, as there is instant access to medical care. Is there any suspicion of an overdose or a medical illness? Again, they will need to go to the ED for medical management in parallel with psychiatric assessment. Is the person particularly aggressive or agitated? This helps to establish if they are best managed in the Section 136 Suite or the ED, whether the police are going to be asked to stay until the outcome of the assessment, whether the assessment needs to be performed in pairs and whether additional security measures will be required. Although the mental health law is explicit about the use of police holding powers, the practicalities of these assessments vary geographically. These are only preliminary considerations and it is best to consult local policies for the procedural aspects of managing patients detained by police.

Preparation: Distilling Key Questions and Reviewing Background Information

As previously discussed, a helpful referral will be asking a specific question or presenting a specific dilemma. It is important to understand what is being asked; if this is not clear, it is prudent to seek clarity from the referring team so that the emphasis of the assessment is appropriate. It is also interesting to know why the question is being asked now. What has changed? Is a mental health concern creating a potential barrier to recovery? It may be straightforward to carry out an assessment acknowledging someone is depressed. The real skill of the CL practitioner is to understand what is contributing to this depression (long hospital admission, missing one’s partner, etc.) and how low mood is impacting their engagement with physiotherapy and thus preventing discharge. The question needs to be clear prior to assessment so the consultation can be goal-orientated and contribute to problem-solving. The literature on specific referrals received is limited (Reference Guthrie, McMeekin and Thomasson9); based on the experience of our team, common examples are summarised in Table 1.1.

| Older adult wards |

|

| General medical wards |

|

| Accident and emergency |

|

Review of Medical Notes

Prior to seeing the patient, it is good to gather as much information as possible. One place to start is exploring the patient’s current hospital admission. Not all hospitals have entirely electronic systems and not all CL services have access to the full electronic patient record (EPR), but this is the case for many services and should be aspired to for others, as there is much information which will support diagnostically and with management planning. Those services which do not have access to the EPR will have to rely on exploration of the paper medical notes and looking at bedside information, such as drugs charts and observations. Verbal handover with the medical teams will also be paramount in these circumstances to ensure all relevant background is available for the assessment. As access to the EPR is the standard to be aspired to, I will proceed as though this is a given, but the following information can be gained through the other means mentioned.

Tip

Paramedic notes are often overlooked and can give you vitally important information about how a patient presented medically and from a mental health point of view prior to arrival in hospital.

Current Presentation

When did the patient come to hospital and why did they come? Is this an acute illness or has there been a gradual deterioration? Did they call for help themselves or has someone else expressed concern? It is important to know whether they have been admitted for a primary psychiatric reason, a primary medical reason or something in between. This may give an indication as to the patient’s current health priority, providing a focus for the assessment. From a practical point of view, it also helps as a guide to how long a patient is likely to be in hospital, as uncomplicated primary psychiatric presentations do not usually need to be in the general hospital for very long. This helps to prioritise referrals and organise timings of assessments.

Progress throughout Admission

You can then proceed to understanding the patient’s journey in hospital so far. Patients can have very long admissions by the time they come to the attention of the CL team, so it is not always practical or time efficient to read all the medical notes. It is, however, very helpful to know all the major events during the admission. Not only does this give longitudinal information for diagnostic purposes, it also helps to understand what the patient has experienced and can be helpful if the patient has questions. If the CL practitioner has the competencies to do so, they may be able to give broad details to the patient, such as ‘you are waiting for test results’ or ‘you have been treated for an infection’, which the treating team may not have had the opportunity to communicate well previously. Helping patients understand what we would consider small details can be hugely therapeutic. The knowledge that a person has been in intensive care, has received a diagnosis of cancer or has been in hospital away from their partner for three months can begin a formulation as to why the patient is experiencing difficulties. This information can be quickly obtained by reading the ED assessment or admission clerking, post-take ward round and the most recent ward round entry, though further notes may need to be consulted for clarity.

Multidisciplinary Team (MDT) Notes

Occupational therapists and physiotherapists have often already taken collateral information from relatives. They will also usually have taken very detailed social histories. They are usually the members of the team who comment on motivation and engagement. They also often complete cognitive tests when concerned. Social workers may have provided information about current care arrangements or care placements. Nursing staff spend the most time with patients and often document behaviours well, including out of hours. They may also have developed the best rapport with patients and so are privy to more intimate and personal details. Make sure to look for notes about discussions with relatives, as this can provide a lot of information, give an idea as to a person’s support in the community and help to understand the most pressing concerns and anxieties affecting a family. Although we have one primary patient, a good deal of therapeutic work is supporting people and their loved ones.

Investigations

Depending on the clinical scenario, it is usually appropriate to look at a patient’s investigations. The reasons for looking at these investigations clearly differ, but common scenarios will help to demonstrate. For example, a patient may have presented with confusion and the ward want a diagnostic opinion. A significant proportion of the assessment will be about good history-taking and gathering collateral information, but investigations can provide meaningful supporting evidence. The blood tests may show raised inflammatory markers, indicating infection, or deficits in vitamin B12 or folate, or hypothyroidism, among other changes. Likewise, septic screens in the form of chest x-rays, lumbar punctures and urinalysis may indicate the presence or absence of an infection. These lend weight to a diagnosis of delirium. The bloods and septic screen may be normal but delirium still present, so this is not diagnostic; it is merely supporting. In addition, brain imaging may show chronic vascular changes or atrophy beyond expected for the patient’s age, which may raise suspicion of an underlying dementia. Another scenario that highlights the utility of appraising investigation results is the referral requesting medication advice regarding psychotropics such as lithium and antipsychotics. It is imperative to look at baseline blood tests – possibly drug levels and ECGs. Blood tests, including drug levels, can also help to ascertain compliance with medication, which again can contribute meaningfully to the risk assessment. In cases of overdoses of medication such as paracetamol, investigations help to give an indication of the severity of the overdose, which not only guides medical management but also contributes meaningfully to the risk assessment.

Medication Chart

The next source of information to be examined is the medication chart. This can offer a wealth of information. Firstly, what are the regular medications the patient is prescribed? This gives an indication of their past medical and psychiatric history. There may also be regular medications which are potential contributors to the current presentation, such as medication with profound anticholinergic effects in a case of confusion. It is important to also know what is new, as these are the most likely offenders. Numerous medications prescribed in the acute setting have psychiatric consequences, such as steroid-induced psychosis, depression associated with some antiepileptics and perceptual abnormalities associated with dopamine agonists. Although medication reconciliation is not the primary role of the CL practitioner, the assessment is another opportunity to ensure that vital medications are not being missed. Depot injection medications have a high risk of being missed as they will not come with the patient in their medicines box and are not always on the primary care physician medications list. Another very important part of reviewing the medication chart is to review medication compliance, as previously mentioned.

Primary Care Physician Care Record

Yet another source of information is the primary care physician care record. Not all areas have an integrated care record, but where it is available it can be a good source of collateral information. It is likely to give some idea of the patient’s baseline and may provide information regarding the onset of the current illness, as well as confirming medications, past medical history and so forth. If there is no integrated care record and the patient is not known to mental health services, it is imperative to get some collateral information from the primary care physician by direct contact.

Medical State on the Day and Barriers to Progress

The next questions pertain to the patient’s current medical status and the barriers to further improvement. The patient may now be medically optimised but awaiting psychiatric review prior to discharge. This patient should be prioritised for review as they could potentially return home. Patients may simply still need ongoing medical treatment as they are still unwell or commonly may be medically optimised but awaiting social care packages. In these cases, there may be a little more time to review, gather further information and organise a management plan. The CL team is often recruited during this time as there are perceived barriers to the patient’s recovery. For example, a common question is whether low mood is affecting patient motivation to engage with physiotherapy and whether an intervention to improve mood would promote their engagement.

Another common question is whether a patient is likely to recover from their confusion (delirium) or whether discharge planning needs to take into account a longitudinal cognitive issue (dementia). Providing this diagnostic assessment contributes meaningfully to their care plan. In essence, understanding the current medical situation and barriers to recovery helps to focus the input of the CL team such that a meaningful contribution can be made to advancing the patient’s journey. It also gives an idea of the length of time available to deliver interventions and support. If a patient is to remain in hospital for a while, we can do some short-term psychological work, commence and monitor medication or do serial cognitive tests. The expectations of the management plan would be more streamlined if the patient is likely to go home in the next couple of days, with the emphasis on ensuring onward community referrals.

Review of Psychiatric Notes

Psychiatric notes can be extensive, but there are key pieces of information that can be rapidly distilled (Table 1.2). Firstly, is the patient known to mental health services? An absence of notes on the psychiatric care record does not necessarily mean the patient has no past psychiatric history. It is important to get collateral information. An obvious source is the primary care physician, as previously mentioned. It is also often necessary to contact mental health services in other local areas. For example, some CL services are based in tertiary centres where patients come from a huge geographic area, so their psychiatric services will also be based out of the area. Some patients have a pattern of presenting to numerous different ED departments, particularly in population-dense areas where there are several large hospitals in very close proximity that may belong to different healthcare providers and organisations. Additionally, patients may have recently moved into the area, so their historical records are based elsewhere.

Table 1.2 Summary of preparatory work prior to assessment

| Medical records | Reason for and circumstances of current admission |

| Progress throughout admission | |

| Multidisciplinary team notes | |

| Investigations | |

| Medication chart | |

| Presentation on the day of assessment | |

| Primary care physician records | Any recent contact with primary care physician |

| Confirmation of medications and diagnosis | |

| Baseline mental state | |

| Psychiatric records | Diagnosis/formulation |

| Do they have a team? Do they have a care coordinator? | |

| Previous admissions? Under section? Informal? When was last admission? Are they on a community treatment order? | |

| Risk history and severity of previous risks | |

| Recent circumstances and stressorsAny indication of worsening of mental state | |

| Do they have a care plan? Do they have a crisis plan? |

When examining the psychiatric care record or asking for salient collateral information from another mental healthcare provider, there are a few key pieces of information to look out for. Does the person have a diagnosis or a formulation? Are they under a community mental health team and what level of support do they receive from the team? Do they have a care coordinator? If they do, it is usually helpful to speak with them, as they should have the best historical knowledge of the patient, as well as an up-to-date appraisal of the patient’s recent mental state and any current concerns. It is also important to know what level of support can be reasonably expected by the care team in the community to help facilitate discharge planning.

There are several important historical factors to look for in the notes. Are there previous diagnostic formulations and treatment regimens, including adverse effects? Has the patient had previous admissions or periods under home-based treatment teams? Are they on a community treatment order? What are the major historical risks and how severe have they been? Are there any forensic implications? Not only does this help to build a picture of a person, but it will also help when deciding how to conduct the assessment in the ED or on the ward. If there are significant risks, considerations need to be made, such as assessments in pairs, the presence of security, the particulars of the assessment room and so forth. Are they a frequent attender of the ED? What usually helps? Once these key historical details have been distilled, it is important to ascertain the current circumstances. Look at the most recent contacts or clinic letters. Have concerns arisen about deteriorating mental state? Have there been concerns about medication adherence or engagement with the community team? Have there been any significant social changes or stressors? What is the current care plan? Is there a crisis care plan or any indication of what helps this particular person in times of need?

Assessment

Although the foregoing sounds like a lot of preparation, it is a fairly swift process, especially once well practised. Taking the time to do the preparation demonstrates to a patient that you are interested and have taken care to learn about them, prevents patients having to repeat potentially traumatizing chunks of their history and contributes to a holistic and patient-centred assessment. It allows the CL practitioner to shape the focus of the assessment before meeting the patient, which should lead to a well-structured and concise review.

Where to Carry Out the Assessment

The final part of preparation is working out where to do the assessment. In an ideal assessment, a space should be provided which offers privacy and is safe. In the ED there should be a dedicated room or set of rooms which meet a certain standard for safety and privacy, for example being free of ligature points and potential missiles, with multiple entries and exits, and equipped with alarms (Reference Baugh, Blanchard and Hopkins10). If all these rooms are in use, it is very likely that a non-specialist room will be used, so all efforts should be made to ensure safety, for example orientation of the room and proximity to the door, access to personal alarms, reviews in pairs or with security available and letting colleagues know where you are. In the general ward, patients can often be seen in the day room or family room and similar considerations have to be made. There are many circumstances where this is not possible, however, such as unwell older patients with dementia or delirium who are bedbound. The assessment then has to be undertaken at the bedside but should be performed sensitively with consideration of the fact that curtains are not soundproofed.

Handover from Nursing Team or One-to-One Staff

At this juncture, take a handover from the nurse looking after the patient that day or the support staff if they are being nursed on a one-to-one basis. This will give the most up-to-date assessment of the patient’s health and behaviour, as well as highlighting any risks or new concerns. If patients do have a member of staff carrying out one-to-one observations with them, it is usually appropriate to ask the staff member to leave while you conduct the assessment to maintain privacy. If there are significant risks, however, this will not be possible. On some occasions, family members may also be present. Again, unless there is a clear reason not to, it is prudent to see patients alone in the first instance and then invite family to join later with the patient’s consent. The patient should always be given the opportunity for a private assessment, even if they ultimately choose to request their family members remain.

Patient Assessment

Finally, we have reached the point of assessment. Once you are with the patient, it is important to introduce yourself and your role and explain why you have come to do an assessment. Although patients should always be made aware that they have been referred to the CL team and should always have consented if they have capacity, this is not always the case. For some, even the mention of mental health can hold stigma, so it is sometimes necessary to contextualize your role and explain how you might be able to help. It helps to ascertain if now is the best time to see the patient. Does the patient have plenty of time to talk before lunch? Are they imminently going for a scan? Are they in pain or nauseated? Have they just received bad news that they need time to process? This can usually be determined by checking with the patient that they feel comfortable and are happy to engage in a conversation right now. Make sure to take a chair and sit with the patient. This demonstrates that you are not just hovering for a few minutes but are committed to spending time with them. It is usually a good idea to let a patient know that you have a general idea of their background, so they do not feel the burden of having to explain everything all over again.

The assessment itself is no different from psychiatric assessments (Table 1.3) in any other setting but, as previously mentioned, there are certain areas which may take more of the focus than others and this will be led by the patient. Be open in your questioning style and allow patients to discuss their priorities. Some specific information will be needed, such as risk assessment, and this can be introduced sensitively by explaining that there are certain questions which are routinely asked. Once the assessment part of the encounter is concluded, a plan needs to be established with the patient. Always ask the patient what they think will help. This is not always possible or achievable as some may simply not know and some may not be able to communicate their needs; finding out what is important to a person is vital when forming a plan. There is a huge range of options of interventions and different services will approach follow-up differently. Capacity assessments are dealt with in more detail in Chapter 16.

| Psychiatric history | Mental state examination |

|---|---|

| Presenting complaint | Appearance and behaviour: Self-care, eye contact, agitation, appropriate clothing, psychomotor activity, guarded/engaged |

| History of presenting complaint | Speech: Rate, tone, rhythm, volume |

| Past psychiatric history | Mood: Subjective, objective |

| Past medical history | Thought: Form and content |

| Medications | Perceptions: All five modalities; subjective, objective |

| Drugs and alcohol | Cognition: Formal or informal; memory, orientation, attention, concentration |

| Family history | Insight: Good, limited, poor, none |

| Social history | Capacity: Decision- and time-specific (see Chapter 19) |

| Personal history | |

| Forensic history | |

| Pre-morbid personality |

Tip

Although it is tempting in a time-pressured environment to record a list, if you are reviewing a patient with a chronic condition, it is worth spending some time asking them about their journey with the condition. This can provide valuable information regarding adjustment to any role loss or change and level of resilience, coping strategies, hopes/fears both now and for the future, how mental health difficulties may have become shaped by the condition or indeed triggered by living with it and whether relationships with family and friends have changed (see Chapter 4).

Getting Collateral

It is usually best to get collateral from family and friends after seeing a patient. By this point, the CL practitioner will have the best sense of who to talk to and also be able to discuss this with the patient. Consent is not required to simply gather information, and sometimes it is necessary to go against a person’s wishes if there are risks involved. However, the patient is at the centre of their care, so it makes sense that they should be asked about this part of their care plan. If specific consent is given to share information, it can be very reassuring for family members, rather than calling simply to take information without giving anything back. The COVID-19 pandemic has been particularly challenging for patients and relatives because of the suspension of visiting in hospitals. Relatives rely on staff for updates about their loved ones, so some of the role of taking a collateral history may actually be about providing information and reassurance where appropriate.

A lot of collateral information will already have been gained by this point from the primary care physician, psychiatric and medical notes, members of the multidisciplinary team and observation in hospital, but families are usually the most persistently involved in a person’s everyday life and hopefully understand their priorities and wishes best. Relatives can be asked to corroborate information already given by the patient and express their concerns about the patient’s mental state or ability to manage prior to admission. For patients who cannot currently communicate because of their illness, families are often vital participants in best-interests discussions in order to formulate treatment plans.

Assessments in Specialist Circumstances

Certain assessments will require some modifications because of specific communication difficulties. Patients may speak limited, if any, English and an interpreter will then be required. All efforts should be made to acquire a face-to-face interpreter, but this is not always achievable and telephone interpretation may have to be used. Using family or friends as interpreters is not good practice as it introduces the risk of misinterpretation, either deliberately or accidentally. Assessments with interpreters will always take more time, so this needs to be planned for when organising the assessment. Make sure to speak to your patient, not the interpreter. It is still possible to build good rapport and engagement by ensuring good eye contact, using the appropriate tone of voice and demonstrating non-verbal communication and active listening.

Some people may have a disability or different communication preferences, which means modifications must be made. Make sure people have their hearing aids or their false teeth in if appropriate to maximise their ability to communicate. If people have speech or hearing impairments but no major cognitive deficit, written communication may be more appropriate, using whiteboards or pens and paper. Speech and language therapists and occupational therapists may be able to support with advice about specific communication aids. It may be helpful to recruit family members, who will be more familiar with a person’s communication preferences. All efforts should be made to maximise a person’s potential to communicate their needs.

Acquired brain injury, dementia, learning disabilities and autism spectrum disorders can be associated with cognitive impairment and/or nuanced communication styles, which may require sensitive reframing of questions and information to maximise understanding. Family members are often good at helping to shape questions into a format that will be understood, as well as interpreting response patterns. Aim for short, clear, simple phrases that require fairly closed answers until you get a better sense of your patient’s communication style, and be aware of the possibility of indiscriminate yes/no answers.

Intervention

Feeding Back to the Treating Teams: Verbal and Written Communication

Once the assessment has finished, it is important to have clear communication with the treating team to share your impression and suggest interventions. It is best practice to have a verbal handover, particularly where urgent matters or risk are involved. Verbal communication also allows questions and concerns to be shared mutually and fosters good working relationships between the CL and medical/surgical teams.

A clear and robust written note is also required after each assessment and an example document can be seen in Figure 1.3. While this is an important source of information, it is often impractical for medical and nursing staff on busy wards to read a document of this length. As such, a brief summary paragraph at the beginning of your documentation should be included with clearly defined headings (diagnostic impression, salient risks identified, management plan, follow-up arrangements).

Figure 1.3 Template for writing a comprehensive note following assessment.

Many patients disclose very personal and intimate details, so be mindful that what is being written will be seen by many and some details are not necessary. Where particularly sensitive information is being shared in a consultation, it is good practice to let a patient know what you intend to write in the notes and to ask whether they would prefer some details to be omitted. Unless there is a risk issue, this can be a perfectly reasonable request.

Formulation

The summing-up of your documentation will be a formulation or impression. This will already have been informally discussed with the patient during the consultation, but a more structured written formulation can help with communication and shared understanding. We very frequently use the bio-psycho-social model in psychiatry, or even a bio-psycho-social-spiritual model, with spirituality not referring to religion but the way a person finds meaning in life (Reference Saad, Medeiros and Mosini11). Table 1.4 shows some examples of contributors to a bio-psycho-social-spiritual formulation.

| Likely to see in consultation-liaison setting | Others | |

|---|---|---|

| Biological |

|

|

| Psychological |

|

|

| Social |

|

|

| Spiritual |

|

|

Case example:

Mary has been in hospital for 12 weeks with pneumonia (biological). She has been very unwell and has suffered from physical deconditioning over the course of the admission (biological). She misses her husband (social) and being in hospital reminds her of her mother passing 10 years ago (psychological). She is desperate to get home but is very upset that she will not be able to look after her husband anymore (social/spiritual). She worries about the meaning of her life now that she cannot do as much (spiritual). This has contributed to her feeling low in mood and hopeless. She will not engage with physiotherapy as she does not see the point.

The interventions required need to focus on Mary’s belief that she has lost meaning/purpose, helping her find a new meaning or a way to understand that she is still a meaningful partner even if her role has changed. Psychological interventions can help her to understand that the contributing factors of being in hospital, away from husband and where her mum died, are temporary and there is potential reversibility in her deconditioning. A formulation helps to understand why she feels like this and give a goal-orientated approach to encourage engagement and eventually returning home.

Another way to approach formulation is the ‘Five Ps’ (Table 1.5) (Reference Macneil, Hasty, Conus and Berk12). This can be used either for general formulation or for risk formulation. These Five Ps (presenting issue, predisposing factors, precipitating factors, perpetuating factors, protective factors) can in turn be broken down into a bio-psycho-social framework. Some authors advocate for a bio-psycho-social-spiritual formulation where appropriate (Reference Saad, Medeiros and Mosini11). Again, using formulation gives a much more nuanced impression, helps to understand an individual’s specific needs and helps to work out goal-orientated solutions.

| Presenting issue | What is the problem? |

|---|---|

| Predisposing factors |

|

| Precipitating factors |

|

| Perpetuating factors |

|

| Protective factors | What keeps a person going? What gives their life meaning? |

Example:

Mary is feeling low in mood. She has no significant past psychiatric history and has had consistent and supportive relationships with her family and her husband. Sadly, her mum died 10 years ago and since then she has been more prone to feeling low (predisposing). Mary started to feel low 6 weeks into admission, as she misses her husband and is feeling very unwell with pneumonia (precipitating). She continues to feel unwell and needs to stay in hospital, and this is preventing her getting back home to her husband and routine (perpetuating). This in turn is making her feel hopeless; she cannot find the motivation to engage in physiotherapy and so sees no progress towards going home (perpetuating).

Recommendations

Broadly speaking, the interventions that are likely to be offered are medications advice; recommendations regarding investigations; referrals to inpatient psychology; referrals to chaplaincy; referrals to community care, whether in primary or secondary care services; referrals to support services for social activation; social care plans; and even possibly psychiatric inpatient admission, to name but a few. There is always room for advocating for patients and it may be that the main intervention is about expressing to the treating team that the patient is not eating as they only eat tomato soup or that they desperately need to get home to look after their aged cat. CL practitioners often have the most time to get to know what is meaningful to a person and this cannot be underestimated.

Follow-Up: Inpatient

For some patients, a single consultation and advice is all that is required, but many will need ongoing input from the CL team throughout their admission. It is important to explain to the patient whether they are likely to be reviewed again to manage expectations, and also to let them know how to access further support while on the ward (clinical psychology, chaplaincy, alcohol and substance misuse CL nursing). Ensure that the ward staff are aware of your plans for follow-up and have a contact number to request further support if needed in the future.

Arranging Follow-Up on Discharge

This requires careful thought and services will vary considerably depending on geographic location. Inpatient admission, brief stays in crisis houses (it is worth checking to see if there are any local to the patient if this is relevant to the presentation) and interventions from home-based treatment teams are generally reserved for severely unwell patients and/or those with salient risk issues that cannot be managed with less intensive input. For patients that require outpatient follow-up, not all will be suitable for community mental health team input, which is generally reserved for patients with affective and psychotic disorders and anxiety disorders (some teams also have a personality disorder pathway). For patients with functional disorders, difficulties adjusting to physical illness or psychiatric sequelae as a result of organic disease, options in the UK generally include clinical health psychology, CL outpatient clinics in both primary and secondary care, specialist functional disorder clinics and neuropsychiatry. Service commissioning for these patient groups is somewhat complex and disjointed across the UK, and as such it is worth making enquiries locally, regionally and even nationally sometimes as neighbouring regions can differ widely in terms of provision.