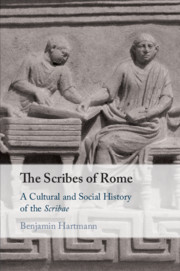

Book contents

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 22 September 2020

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Scribes of RomeA Cultural and Social History of the <I>Scribae</I>, pp. 176 - 200Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2020