1 - Making Parchment For Books

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 16 July 2022

Summary

Parchment, like a book, was made to be durable. Making parchment used up animal materials sustainably, and the end product could be conserved and re-used in all kinds of ways. As discussed in the introduction, parchment's hard-wearing potential relies on the intrinsic material properties of skin. Cultivated by craftsmen, skin's long-lasting durability when made into parchment provided the foundations for both uses and re-uses. Throughout, this chapter is informed by codicological studies of medieval book production, as well as extant medieval manuscripts and recipes for making parchment. Fifteenth-century manuscripts provide evidence for their production in their form, and recipes offer instruction and information about book-producing crafts. Considered in conjunction with one another, manuscripts and recipes reveal efforts made by fifteenth-century people to enhance the durability of parchment, and to use resources and their by-products as efficiently as possible. There was a ‘nose-to-tail’ approach, which avoided waste and used the whole animal.

To explore these practices, the stages of parchment production are re-evaluated here, step-by-step, from farm to writing table. Though these stages are well known to specialists, this chapter offers a new description of parchment-making as an exercise in cultivation and conservation. The discussion begins with animal husbandry in the field, and ventures through various supply chains, into the hands of slaughtermen. Then, the dead animal matter, be it as raw hide or skin, travels to parchmeners (there is no consensus on the spelling of this word, which is found as parchmenter, parchemyner, parchminer and parchmyner).Here the discussion appraises the processes, time, care, skills, tools and additional resources required to turn hide or skin into usable parchment. Finally, the ‘luxury commodity’ of parchment is available for use and for re-use.Alongside the main product of this process, parchment, there are by-products such as gelatine and glue made from bits of the carcass or trimmings of skin; and, furthermore, lower grade or damaged parchment could be used, or efforts could also be taken to sustain it by repair. Re-evaluating each stage of production indicates how medieval parchment production embraced and embodied sustainability.

But books could also be made from paper. Fifteenth-century paper was made from ‘cellulose (flax, hemp, linen), which in late medieval Europe was usually obtained from cloth rags or ship sails (or even recycled scrap paper)’.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

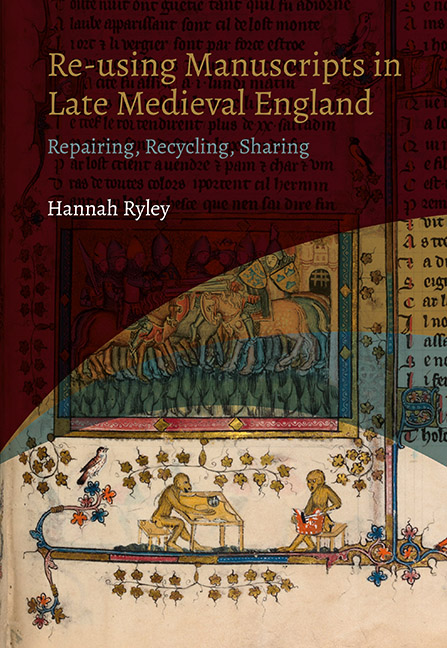

- Re-using Manuscripts in Late Medieval EnglandRepairing, Recycling, Sharing, pp. 19 - 60Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2022