Introduction

Visitors to Bosnia-Herzegovina (BiH) often spend a few days in the capital city, Sarajevo, before travelling to Mostar in the south-west of the country, and from there across the border into Croatia. Few tourists head to Central Bosnia, despite its relative proximity to Sarajevo. An area rich in both history and natural resources, including the spectacular mountains of Vlašić and Kruščica, this part of BiH was the scene of fierce fighting between the Army of BiH (ABiH) and the Croatian Defence Council (HVO) during the 1992–1995 Bosnian war. In April 1993, the HVO launched an attack on the Lašva Valley, culminating in the massacre of more than 100 Bosniaks in the village of Ahmići. I visited Ahmići for the first time in July 2008 and since then I have returned many times. I confess that I have a deep attachment to the place. Each time that I am there, I find myself thinking about pre-war Ahmići and wishing that I had been able to experience – albeit as an outsider – the village life that Bosniaks and Croats (Bosnian Croats) alike speak about with great nostalgia. They used to visit each other’s houses; jointly celebrate Christmas and Bajram (Eid); watch football matches together.

Today, although the village is peaceful, there is a distance between people and relationships have changed. The absence of a sense of community and the weakening of community ties constitute important resource deficits. Such deficits, moreover, exist alongside broader systemic and environmental stressors – including political rhetoric and segregated schooling – that have helped to keep the past alive. Drawing on my most recent fieldwork in Ahmići, carried out in July 2019, this chapter argues that, while some individuals have demonstrated resilience, despite suffering huge losses, overall the social ecologies in which they live offer few protective resources. This, in turn, has important implications for transitional justice, which is partly about social repair (Reference FletcherFletcher and Weinstein, 2002).

Several prosecutions took place at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) in relation to the crimes committed in Ahmići. However, these trials had few positive effects and arguably contributed to further entrenching inter-ethnic divides; the supposed transformative impact of the ‘truths’ established within the ICTY’s courtrooms critically neglected the wider ecologies that have shaped popular interpretations of and responses to those truths. The broader issue is that transitional justice, in both theory and practice, has significantly overlooked the concept of resilience, which is quintessentially about entire systems (see Chapter 1) – and about ‘the interactions between an individual’s environment, their social ecology, and an individual’s assets’ (Reference Liebenberg and MooreLiebenberg and Moore, 2018: 3). This chapter outlines the case for a social-ecological reconceptualisation and reframing of transitional justice. Operationally linking this to adaptive peacebuilding (Reference de Coningde Coning, 2018), it argues that transitional justice processes can potentially contribute to resilience – which overlaps with core transitional goals such as peace and reconciliation – by giving more attention to the social ecologies that necessarily shape processes of dealing with the past.

Massacre in Ahmići, 16 April 1993

According to the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE, 2018: 7), ‘The conflict in BiH … resulted in an estimated 100,000 dead and 2.2 million displaced. The mixed Croat and Bosniak cantons of Zenica-Doboj, Central Bosnia and Herzegovina-Neretva were all areas of intense fighting, which resulted in the substantial displacement of one of the two ethnic groups’. At the start of the Bosnian war, the ABiH and HVO were allies against the Army of Republika Srpska (VRS). The military alliance between the two armies, however, gradually began to break down, and a Trial Chamber of the ICTY found ‘compelling evidence to the effect that, starting in mid-1992, tensions and animosity between Croats and Muslims rapidly escalated’ (Reference Zoran Kupreškić, Kupreškić, Kupreškić, Josipović, Papić and ŠantićProsecutor v. Kupreškić et al., 2000: para. 125). The first major flare-up in Central Bosnia occurred in October 1992 (Reference Zoran Kupreškić, Kupreškić, Kupreškić, Josipović, Papić and ŠantićProsecutor v. Kupreškić et al., 2000: para. 163). The Vance-Owen Peace Plan, in January 1993, further contributed to the deterioration in relations between the two sides. It proposed the establishment of ten largely autonomous provinces or cantons in BiH, each of which would have an ethnic majority. Bosnian Croats were to be the majority in three cantons, including canton 10 – Central Bosnia (Reference Dario Kordić and ČerkezProsecutor v. Kordić and Čerkez, 2001: para. 559). According to the ICTY, ‘In the minds of Croatian nationalists, and in particular of Mate Boban [the Bosnian Croat leader], this meant that Province 10 was Croatian’ (Reference Tihomir BlaškićProsecutor v. Blaškić, 2000: para. 369; see also Reference HoareHoare, 1997: 132).

From January 1993, relations between the ABiH and the HVO further deteriorated as the latter sought to establish its authority over the aforementioned cantons. After ABiH forces ignored an ultimatum to either surrender to the HVO or leave the cantons by 20 January, ‘Croatian forces embarked on a series of actions intended to implement the “Croatisation” of the territories by force’ (Reference Tihomir BlaškićProsecutor v. Blaškić, 2000: para. 372). The situation started to come to a head in mid-April 1993. The HVO had set a deadline of 15 April for the then Bosnian President, the late Alija Izetbegović, to sign an agreement that would place ABiH forces in the three cantons under HVO command. This deadline passed and, at 8 a.m. on the same day, ABiH forces abducted an HVO brigade commander and killed his four escorts. This was one of the ‘provocations’ from the side of the ABiH that Croats in Ahmići often refer to when discussing subsequent events. A Trial Chamber of the ICTY found ‘direct evidence that the HVO planned an attack for the next day [16 April] at a series of meetings that afternoon and evening’ (Reference Dario Kordić and ČerkezProsecutor v. Kordić and Čerkez, 2001: para. 610).

At 5.30 a.m. on 16 April 1993, the HVOFootnote 1 launched a concerted attack on the village of Ahmići (and on several other towns and villages in the Lašva Valley). Only Bosniak homes were set alight (Reference Miroslav BraloProsecutor v. Bralo, 2005: para. 12). Some Bosniak villagers were shot and killed as they tried to escape. In total, 116 people were killed in Ahmići that day. More than twenty victims are still missing. Bosniaks started to return to Ahmići from the late 1990s onwards. Every year on 16 April, a memorial service takes place – starting in Stari Vitez where many of the victims are buried and ending at the donja džamija (lower mosque) (see Figure 3.1) – to remember and honour the dead.

Figure 3.1 Ahmići memorial to the 116 men, women and children who were killed on 16 April 1993.

In Ahmići, there are many examples of individual resilience, in the sense of ‘positive adaptation within the context of significant adversity’ (Reference Luthar, Cicchetti and BeckerLuthar et al., 2000: 543). Resilience, however, is not only about individuals. As Reference Ungar and LiebenbergUngar and Liebenberg (2011: 127) underline, ‘resilience is the qualities of both the individual and the individual’s environment that potentiate positive development’. In Ahmići, resource deficits and environmental stressors have critically hampered the community and community relations. These same deficits and stressors, which contributed to limiting the on-the-ground impact of the ICTY’s work – both in Ahmići and in BiH more generally – ultimately underscore the need for a social-ecological reconceptualisation of transitional justice.

Individual Resilience in a Divided Community

My previous research in Ahmići, in 2008 and 2009, focused on inter-ethnic relations and reconciliation (Reference ClarkClark, 2012, 2014). More recently, in July 2019, I spent two weeks in the village. I wanted to explore how people had rebuilt their lives, what resources they had used to do so and the extent to which transitional justice processes – and specifically trials conducted at the ICTY – had contributed to fostering resilience, as manifested in the interactions between individuals and their environments (Reference Berkes and RossBerkes and Ross, 2013: 7). In total, I conducted ten semi-structured interviews with six men and four women. Seven interviewees were Bosniaks and three were Croats. In addition, a fourth local Croat (female) agreed to respond to questions via email, maintaining that she did not have time to participate in a face-to-face interview.

The relatively small number of interviews undertaken reflects the difficulties of doing research in this particular community. The place has an empty feel and there is no sense of bustling village life. Hence, there are few opportunities to interact with people. It is as if life in Ahmići today primarily takes place behind closed doors. Many people are also tired of telling their stories and dredging up painful memories from the past. The village receives large crowds on 16 April each year and continues to be the subject of media interest (see, e.g., Reference DajićDajić, 2017). I relied primarily on a snowball sampling strategy, particularly for locating Croat participants. A local contact facilitated the interviews with Bosniak participants. Interviews typically lasted around forty-five minutes and were conducted in the interviewees’ homes in the local languages (Bosnian, Croatian). It would have been impossible to write this chapter while anonymising the name of the village. However, any details that could help to identify the interviewees have been removed.

Regardless of their ethnicity, all interviewees expressed a deep sense of pain and hurt (Reference ClarkClark, 2020a). As one of them underlined, ‘[a]t the end of the day, we are all losers’ (author interview, 9 July 2019). The Bosniak interviewees had lost several close family members in the attack on Ahmići. One of the Croat interviewees had lost family members in an ABiH attack on a nearby village. All interviewees, moreover, had lost the community that once existed, as well as neighbours and friends. More than twenty-five years on, the past thus remains raw. In the words of a survivor of the massacre who lost nine family members, ‘[t]ime goes by, the years pass by and the memories are fresh, the sadness is the same’ (cited in Anadolija, 2019). Nevertheless, people have rebuilt their lives, and the interview data provided valuable insights into some of the ways that they have done so. Three particular points stand out in this regard.

The first is that the attack on Ahmići resulted in the loss and destruction of multiple resources. The victims lost their homes, their animals, their livelihoods, their way of life, their sense of belonging and security. When asked how he had dealt with everything that happened in Ahmići, for example, one interviewee stressed: ‘You can’t describe it.’ He used to work hard and he had invested everything in his home; ‘[i]t was all destroyed in an instant’. What had most helped him to deal with everything that happened, he explained, was his desire to ‘return to where I was born’ (author interview, 8 July 2019). His land was charred and neglected, but it was still his ‘dom’ (home) and a fundamental resource, highlighting the fact that – particularly in rural parts of BiH – people often have a deep attachment to land (see, e.g., Reference Tuathail and O’LaughlinTuathail and O’Laughlin, 2009: 1052).

Another intangible resource that both this interviewee and several others indirectly spoke about was their desire to live – and what they frequently referred to as ‘the fight for life’. Speaking only briefly about her own experiences on 16 April 1993, one interviewee stressed: ‘You have to live. You carry inside you everything that you saw and survived, but you have to fight and to go forward’ (author interview, 9 July 2019). The wish to live is an elemental resource that has similarly emerged prominently from other research on traumatic events. In his work with child survivors of the Holocaust, for example, Reference ValentValent (1998: 520) found that many of them ‘cited an inner surge or compulsion to live, a will to survive, as the most important factor in their survival. They used whatever capacities they had to do so’. In this way, he linked their resilience to ‘the surge of life they manifested, a kind of sacred connection with a wider life force’ (Reference ValentValent, 1998: 522–523).

For some interviewees, this ‘surge of life’ was closely connected to their faith. One interviewee who lost several members of his family in the attack on Ahmići stressed that, whenever he closes his eyes, he can see all of them and the suffering they went through. However, he also underlined that ‘[y]our relationship with God and prayer bring you some solution and relief’ (author interview, 11 July 2019). Faith had, in some cases, also contributed to meaning-making. One particular interviewee stood out in this regard. ‘It is very difficult to come to terms with what happened in Ahmići’, she reflected, ‘but if you believe that something had to be, this helps you to deal with it’ (author interview, 16 July 2019). According to Panter-Brick, ‘What matters to individuals facing adversity is a sense of “meaning-making” and what matters to resilience is a sense of hope that life does indeed make sense, despite chaos, brutality, stress, worry, or despair’ (Reference Southwick, Bonanno, Masten, Panter-Brick and YehudaSouthwick et al., 2014). This particular interviewee had found a sense of meaning in her conviction that events in Ahmići were Allah’s will, and this, in turn, had helped her to move forward.

The second point to underscore is that resilience is not simply about having access to what Reference UngarUngar (2008: 221) has termed ‘health-enhancing resources’, but also about the clustering of those resources. In his work on Conservation of Resources Theory, for example, Reference HobfollHobfoll (2001: 349) argues that ‘[t]here is strong evidence that resources aggregate in resource caravans in both an immediate and a life-span sense’. Elaborating on the concept of ‘resource caravans’, he further explains that ‘having one major resource is typically linked with having others, and likewise for their absence’ (Reference HobfollHobfoll, 2001: 350). Illustrating this, one of the interviewees expressed a strong sense of contentment. She had many resources, through her own efforts, and in this regard her ‘caravan’ was full. Describing herself as a ‘cheerful person’, she spoke with great pride about her children and stressed the importance of making the most of life, underlining that she had overcome many adversities (author interview, 9 July 2019).

Another interviewee, in contrast, had various material resources yet his ‘caravan’ was somewhat empty. He led a solitary life and explained that he felt bored and frustrated as he saw no prospects for himself in BiH (author interview, 8 July 2019). Similarly, the interviewee who had stressed his desire to return to Ahmići and to his land was similarly dissatisfied with life. He had not worked for many years and repeatedly complained that no one had helped him and his wife, overlooking the fact that external donors had funded the reconstruction of the family’s destroyed home (author interview, 8 July 2019). While his ‘caravan’ was relatively bare, he was not doing anything to change this and his entire demeanour exuded a sense of sadness and defeatism. The past had taken so much away from him and, although he had fulfilled his wish of returning to his land, he appeared to be observing life rather than actively living it.

The third point is that interviewees’ answers revealed a critical absence of community in Ahmići, thus restricting what the community environment provides for resilience (Reference UngarUngar, 2017: 1282). As Reference Liebenberg and MooreLiebenberg and Moore (2018: 2) observe, ‘[i]t is now widely accepted that resilience is associated with individual capacities, relationships and the availability of community resources and opportunities’. When asked about resources within the community, one interviewee underscored the importance of land and agriculture (author interview, 11 July 2019). Illustrating this point, another interviewee had been out picking fruit and she was going to use them to make teas (author interview, 17 July 2019). Overall, however, interviewees significantly struggled with the question about community resources. Some interviewees talked about their pre-war resources. Some interviewees made vague references to the mjesna zajednica (local community association) as a body that can offer limited help. Yet, when asked to elaborate, they were unable to provide more details. Moreover, while some interviewees claimed that there is one mjesna zajednica for Ahmići, others maintained that Bosniaks and Croats each have their own mjesna zajednica. The fact that the interviewees gave such conflicting answers is an important indicator of a lack of community engagement.

What also emerged was a strong conviction on the part of some of the Bosniak interviewees that, as regards resources, there is unequal treatment. One interviewee, for example, complained that Bosniaks have to pay more for land than Croats and that the latter had blocked his attempts to purchase some land. He further insisted that Bosniaks have a second-class status within the municipality of Vitez (which encompasses Ahmići) (author interview, 8 July 2019).Footnote 2 Another interviewee maintained that, as a Bosniak, she has no rights and that the Croats have taken everything for themselves (author interview, 9 July 2019). While many such assertions were unsubstantiated and/or could not be verified, the common feeling among Bosniaks that they do not have the same rights and benefits as their Croat counterparts has undoubtedly contributed to further undermining a sense of community. Equating resilience with community processes, Reference Comes, Meesters and TorjesenComes et al. (2019: 126–127) argue that ‘the ability to take part, benefit from and contribute to these processes becomes central if we are striving to ensure social justice’. In Ahmići, the perceived absence of social justice has undermined community processes that might contribute to bringing people together, including how the community deals with adversity and crises (Reference MagisMagis, 2010: 405).

Ahmići, in short, is a fragmented community where the overwhelming impression is that people simply get on with and live their own lives (see Figure 3.2). Some of them have demonstrated resilience in doing so, drawing on their own individual resources to move forward. However, Ahmići cannot be accurately described as a resilient community – the sum of its parts – because it has not dealt with what happened in 1993 as a community. A crucial reason for this is the existence of multiple systemic factors – which are central to the chapter’s insistence on a social-ecological reframing of transitional justice – that have not allowed the community to come together as one and rebuild the social connections that are ‘at the heart of resilient communities’ (Reference Ellis and AbdiEllis and Abdi, 2017: 290).

Multi-Systemic Hindrances to Fostering Community Resilience in Ahmići

Brightly coloured Russian dolls can be purchased in BiH, particularly in tourist areas like Baščaršija in Sarajevo and the area around the Old Bridge (Stari Most) in Mostar. Stiles et al. invoke the analogy of Russian dolls to apply personal space boundary theory to traumatised adults in therapy. Likening the dolls to four different levels of personal space, they argue: ‘The largest outermost doll is the superficial public self. The next smaller doll is the thoughts and feelings perceived as “acceptable” to the client. The next smaller doll is the “deepest thoughts, feelings, secrets, and sins” of the client, and the innermost doll is the “inner spirit”’ (Reference Stiles, Wilson and ThompsonStiles et al., 2009: 69). Extending the analogy, but in a different direction, I argue that Ahmići can be likened to a medium-sized doll. The smaller dolls inside it represent individual lives, but larger dolls – representing broader systemic influences – surround and encase it.

The massacre in Ahmići did not occur in a vacuum. It took place in the context of the Bosnian war, and both Bosniak and Croat nationalists subsequently co-opted events to promote and support their particular and conflicting ethno-narratives. These political machinations and persistent attempts at ethnic outbidding (Reference ZdebZdeb, 2017) themselves take place within a broader constitutional system and structure where ethnicity is the central pivot. Fundamentally, ‘The unique way in which Bosnia’s Constitution has been realised allows ethnicity to become the most salient identification marker in political life’ (Reference PiersmaPiersma, 2019: 937). The country’s tripartite Presidency, the plethora of ethnic-based political parties and the fact that ‘the confederal element of the Bosnian settlement transcends BiH’s borders’ (Reference BoseBose, 2005: 327) – reaching into neighbouring Croatia and Serbia – powerfully highlight this. Involvement from these neighbouring states, moreover, also contributes to stoking nationalist flames.

In 2019, for example, the Bosniak member of the BiH presidency, Šefik Džaferović, criticised the then President of Croatia, Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović, for comments that she had made about Croats in BiH. During a speech in Mostar in November 2019, she told a large audience: ‘Croats have two homes, the Republic of Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina, but we are one soul and one nation. Therefore I will not stop until Croats in BiH secure what belongs to you historically, politically and constitutionally; that is, total equality and the realisation of your rights as a constituent people’. She insisted that anyone who expects Croats to simply kneel down and disappear from BiH is deceived, and further offered a guarantee that she would not repeat her two predecessors’ neglect of Croats in BiH (Radio Reference SarajevoSarajevo, 2019; author’s own translation). President Džaferović responded by accusing Grabar-Kitarović of being part of ‘retrograde powers’ that seek to create ethnic and territorial divides. Claiming that she had charged Bosniaks of wanting BiH for themselves, Džaferović underlined that Bosniaks had been victims of genocide and expelled from huge swathes of territory (Hina, 2019). The victim narratives that both Presidents promoted highlight the existence of meta hermeneutical/interpretative frameworks, fundamentally intersecting with political systems, that strongly shape popular discourse about the Bosnian war. It is within these systemic dynamics that everyday life in Ahmići takes place.

In their work with internally displaced people in Lebanon, Reference Nuwaydid, Zurajk, Yamout and CortasNuwayhid et al. (2011: 511) argue that one factor that helped to build resilience was ‘a strong communal identity united around a common cause’. This common cause, in turn, ‘provided the affected population with a sense of collective identity’ (Reference Nuwaydid, Zurajk, Yamout and CortasNuwayhid et al., 2011: 511). Shiite communities particularly bore the brunt of Israeli military attacks (Reference TelhamiTelhami, 2007: 26), and ‘shared destiny and the feeling of being collectively targeted strengthened the communal cohesiveness of the affected community’ (Reference Nuwaydid, Zurajk, Yamout and CortasNuwayhid et al., 2011: 512). In Ahmići, no strong sense of communal identity exists, due to wider systemic influences that encourage division and the maintenance of ‘us’/‘them’ boundaries. There is a critical absence of space for discussion and reflection about the pain and hurt that exist on both sides (Reference ClarkClark, 2020a) – or for the development of shared narratives. Bosniaks continue to grieve for their loved ones who perished on 16 April 1993. One interviewee underscored that ‘[t]here are a lot of tears and sadness that cannot be wiped away’ (author interview, 11 July 2019). Croat interviewees, both in my most recent and previous research, have often expressed a sense of hurt that, as they see it, the suffering of their own people has been ignored (Reference ClarkClark, 2014: 80). Claiming that many ‘untruths and lies have been told about Ahmići’, one interviewee insisted that nobody talks about crimes committed in places such as Buhine Kuće.Footnote 3 Politics, he maintained, was the reason (author interview, 11 July 2019).

While there is a critical absence of community cohesion in Ahmići, another type of cohesion arguably exists. Reference OlsonOlson’s (2000) Circumplex Model of Marital and Family Systems, which emphasises cohesion as one of its three key elements (alongside flexibility and communication), identifies four different levels of cohesion – namely disengaged (very low), separated (low to moderate), connected (moderate to high) and enmeshed (very high). The model hypothesises that ‘the central or balanced levels of cohesion (separated and connected) make for optimal family functioning. The extremes or unbalanced levels (disengaged or enmeshed) are generally seen as problematic for relationships over the long term’ (Reference OlsonOlson, 2000: 145). In a very different context, Reference WintonWinton’s (2008) work utilises the model in relation to the crime of genocide, and specifically as a way of explaining different perpetrator group dynamics. ‘Enmeshed cohesion’, he argues, ‘is demonstrated by a high level of emotional closeness within the perpetrator groups’ (Reference WintonWinton, 2008: 607). The group is perceived as ‘one big family’, and high levels of loyalty are demanded. Deviations in this regard are punished. In contrast, emotional distance, low levels of loyalty and high levels of group member independence are characteristic of disengaged cohesion (Reference WintonWinton, 2008: 607). The concept of enmeshed cohesion is particularly pertinent to Ahmići and illustrates – at least in part – the feasibility of applying Olson’s model to communities and societies as a whole.

In Ahmići, there are high levels of ethnic-based enmeshed cohesion in the sense of loyalty to a particular narrative, especially on the Croat side. In the hours after the massacre, the head of the British battalion within the United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR) in BiH, Colonel Bob Stewart, walked through charred shells of people’s former homes. Coming across three HVO soldiers in a vehicle, he asked them who was responsible for the massacre. All of them denied any knowledge or involvement (SENSE Centre, 2019). This denial has persisted. Local Croats, for example, commonly distance themselves from the events of 16 April 1993. One interviewee repeatedly insisted that he would never have returned to Ahmići if he had known what was going to happen (author interview, 16 July 2019). Another interviewee had been in the HVO but maintained that, at the time of the attack, he was not in Ahmići and did not know what was happening (author interview, 11 July 2019). Some locals blame ‘outsiders’ or a few rogue elements (Reference ClarkClark, 2012: 245).Footnote 4 Furthermore, they often deflect attention from what happened in Ahmići by highlighting Croat suffering, in the same way that the conspicuous memorial cross, erected in the grounds of the local Catholic Church, only acknowledges Croat deaths in what it refers to as the 363-day Muslim siege of Vitez.

In April 2010, Ivo Josipović was the first Croatian President to visit Ahmići and he received a warm welcome. According to the then head of the Organisation of 16 April, the visit was ‘first and foremost an expression of good will’ that he believed would ‘contribute to establishing true neighbourly relations in Ahmići’ (Radio Reference SarajevoSarajevo, 2010). The foundations for such relations, however, are necessarily highly unstable when they are linked to broader systems that contribute to fostering denial and the glorification of war criminals. In 2014, for example, the convicted war criminal Dario Kordić (discussed in the next section) landed at Zagreb airport following his release from prison. Bishop Vlado Košić was waiting to welcome him. Taking his hand, the Bishop declared that Kordić’s patriotism should be a model to other Croats (Reference Belak-KrileBelak-Krile, 2019). Kordić’s support from within the Catholic Church in Croatia – which often intervenes in politics (Reference VladisavljevićVladisavljević, 2019) – has also provided him with several opportunities to speak in public. In April 2019, at the invitation of the Croatian priest Damir Stojić, Kordić delivered a lecture at a student dorm in Zagreb and spoke about how he had found God during his time in prison (Dnevnik, 2019).Footnote 5 He has not spoken publicly about what happened in Ahmići or expressed any remorse.Footnote 6

If indicators of enmeshed cohesion include ‘loyalty to the perpetrator group’ and ‘fear of negative sanctions for dissenting from the perpetrator view’ (Reference Winton and UnluWinton and Unlu, 2008: 49), these indicators are present in Ahmići – among both Croats and Bosniaks. During my most recent and my previous research in the village, Croats always refrained from denouncing convicted war criminals (this will be discussed more in the next section), and, in some cases, they directly or indirectly expressed support for them. At the same time, however, there is little space or incentive for Bosniaks to dissent from a powerful metanarrative – exemplified by the persistent instrumentalisation of the 1995 Srebrenica genocide (Reference NielsenNielsen, 2013: 30) – that underlines Bosniak suffering and victimhood, and to acknowledge ABiH crimes against Croats in places such as Buhine Kuće and Križančevo Selo.Footnote 7 To cite Reference OrentlicherOrentlicher (2018: 283), ‘many Bosnians [regardless of ethnicity] feel strong community pressure not to condemn atrocities committed by their own ethnic group’.

The education system has further contributed to fostering enmeshed cohesion. Reference LaketaLaketa (2019: 175) notes that ‘[s]egregated educational landscapes work forcefully to entrench fixed notions of identity so that any deviation from the norm becomes highly visible’. In BiH, the most striking example of segregation within the education system (or, more accurately, systems) is ‘two schools under one roof’, whereby young people from different ethnicities attend the same school in different shifts or use different parts of the building. There are fifty-six schools operating as ‘two schools under one roof’ in three particular cantons within the BiH Federation (OSCE, 2018: 6). Central Bosnia Canton, which encompasses Ahmići, has the largest number of divided schools (Reference PiersmaPiersma, 2019: 941).Footnote 8 In a 2018 report, the OSCE (2018: 4) stressed that what is common to all of these divided schools ‘is that they segregate children, and through this segregation teach them that there are inherent differences between them’. In this way, divided schools not only impede reconciliation and long-term stability (Reference SwimelarSwimelar, 2013: 172). They also undermine resilience, and in particular the ‘community capacity’ that might be used to ‘solve collective problems and improve or maintain the well-being of a given community’ (Reference ChaskinChaskin, 2008: 70).

In short, Ahmići is not a resilient community that has positively adapted to the shocks and stressors that occurred during the Bosnian war. Rather, it can be more accurately described as an ethnically based enmeshed community that responds to, and is constrained by, broader systemic influences. These influences have also reflected heavily on transitional justice work – and on the fact that it has had little impact on resilience.

Transitional Justice, the ICTY and Resilience

In May 1993, as the war in BiH continued to rage, the UN Security Council used its Chapter VII powers (dealing with threats to international peace and security) to establish the ICTY, the first international war crimes tribunal since the post-World War II Nuremberg and Tokyo Tribunals. During the Tribunal’s early years, several defendants stood trial for the crimes committed in Ahmići in April 1993. Two of the most important were Tihomir Blaškić and the aforementioned Dario Kordić, and their cases continue to provoke the most discussion in Ahmići today.

Blaškić was the HVO commander in Central Bosnia. A Trial Chamber of the ICTY assessed that he had ordered the attacks that gave rise to the crimes committed in Ahmići and other villages in the Lašva Valley (Reference Tihomir BlaškićProsecutor v. Blaškić, 2000: para. 437). It further found that ‘[i]n any event, it is clear that he never took any reasonable measure to prevent the crimes being committed or to punish those responsible for them’ (Prosecutor v. Blaškić, 2000: para. 495). On the basis of Blaškić’s individual criminal responsibility and superior criminal responsibility (reflecting his position as a commander), the Trial Chamber convicted him of crimes against humanity, violations of the laws or customs of war and grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions. It imposed a forty-five-year custodial sentence. The Appeals Chamber, however, admitted additional evidence and opined that the Trial Chamber had made a number of errors, including with respect to the constituent elements of command responsibility (see, e.g., Reference Tihomir BlaškićProsecutor v. Blaškić, 2004: paras. 372–422). It accordingly reversed several of Blaškić’s convictions and reduced his sentence to nine years’ imprisonment. Just four days later, he was granted early release.

Kordić was the former president of the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) in BiH. In 2011, the ICTY convicted him of crimes against humanity, violations of the laws or customs of war and grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions and sentenced him to twenty-five years’ imprisonment (upheld on appeal). The Appeals Chamber found that ‘a reasonable trier of fact could have concluded beyond reasonable doubt that Kordić, as the responsible regional politician, planned, instigated and ordered the crimes which occurred in Ahmići on 16 April 1993’ (Prosecutor v. Kordić and Čerkez, 2004: para. 700). In 2014, he was granted early release.

The cumulative effect of the trials that took place at the ICTY was to further entrench ethnic divisions in Ahmići (Reference ClarkClark, 2014: 63–63, 79–80), thereby undermining the function of both the community and systems of justice as potential resilience resources. The fundamental issue is that, for both Bosniaks and Croats alike, justice was not done. For many Bosniaks, the fault lies not only with the Tribunal itself (common complaints are that its sentences were too lenient) but also with their Croat neighbours. One interviewee reflected: ‘The trials did not have any positive influence. For Croats, Kordić is a hero. He and Blaškić are viewed as national heroes.Footnote 9 So how is this useful or just?’ (author interview, 8 July 2019). Another interviewee stressed that, while she is glad that at least some perpetrators have been held to account, it greatly bothered her when Croats celebrated the release of people like Kordić (author interview, 16 July 2019).

For Croat interviewees, however, the very fact that Blaškić and Kordić stood trial was itself an injustice. One interviewee lambasted the ICTY as ‘a disastrous court that prosecutes innocent people’. While emphasising that he was not defending people like Kordić and Blaškić, he maintained that the Croats were completely surrounded in the Lašva Valley and that the ABiH made a huge mistake by not leaving a way out for them (author interview, 16 July 2019).Footnote 10 Another interviewee insisted that people like the Kupreškićs and Drago JosipovićFootnote 11 have no idea what happened in Ahmići and should have never gone on trial. Questioning why ‘the real perpetrators’ have not been prosecuted, although he failed to elaborate on who these individuals are, he stressed that many lives had been destroyed due to false testimony and lies (author interview, 11 July 2019). In a similar vein, a third interviewee opined that ‘Unfortunately, many war criminals and commanders are free, and innocent people … were found guilty’. She further argued that: ‘Mothers, spouses, children did not get the truth from the Hague Tribunal. Justice did not win’ (email correspondence with the author, 24 July 2019).

These examples underscore the fact that the Tribunal’s work did not contribute to resilience in Ahmići, at any level. Yet, it is also important to stress that resilience was never part of the Tribunal’s mandate, and this highlights a broader point. Transitional justice can potentially affect resilience, positively or negatively, in myriad ways (Reference Wiebelhaus-Brahm, Duthie and SeilsWiebelhaus-Brahm, 2017). As one illustration, ‘proponents claim transitional justice processes can promote such outcomes as reconciliation, trust, and the rule of law, which development practitioners associate with more resilient societies’ (Reference Wiebelhaus-Brahm, Duthie and SeilsWiebelhaus-Brahm, 2017: 142). It is striking, therefore, that the concept of resilience remains heavily neglected within the ever-growing field of transitional justice, including within the extensive body of scholarship that exists on the ICTY’s work. Several authors have explored whether the Tribunal’s work aided reconciliation (see, e.g., Reference ClarkClark, 2014; Reference Hodžić and SteinbergHodžić, 2011; Reference Meernik and GuerreroMeernik and Guerrero, 2014) – but not resilience. This section emphasises resilience as a new lens that brings an important systemic dimension to discussions about the Tribunal’s impact and legacy – and about transitional justice more broadly.

According to the ICTY (n.d.), for example, one of its achievements was that it ‘established beyond a reasonable doubt crucial facts related to crimes committed in the former Yugoslavia’. This is a deeply myopic assertion that overlooks critical systemic factors that have hindered and obstructed social acceptance of those facts. It would be equally myopic, however, to simply criticise the ICTY in this regard. Its claim exposes a more intrinsic and larger issue with transitional justice itself, as both a theory and a practice. Transitional justice processes are quintessentially about ‘dealing with the legacy’ of past human rights violations, with the aim, inter alia, of delivering justice, establishing the truth and fostering reconciliation (United Nations, 2010: 2). Yet, their primary focus on individuals – and specifically on victims and perpetrators – means that they often neglect the wider social ecologies that critically contribute to shaping the legacies of mass human rights abuses. This chapter has demonstrated that one of the legacies of the massacre in Ahmići is a broken and disjointed community.

The essential point is that, in order to understand this legacy, it is not sufficient only to focus on the crime itself or on the ICTY’s shortcomings. It is also imperative to take account of broader systemic factors, as explored in the previous section, that have influenced how people in Ahmići have dealt with the past – and how they responded to the ICTY’s work. Ultimately, what is needed is a social-ecological reframing of transitional justice that better reflects the realities of complex individual – environment interactions (Reference ClarkClark, 2020b). Such a reframing, in turn, has important implications for developing adaptive peacebuilding.

Social-Ecological Transitional Justice and Adaptive Peacebuilding

Various scholars have written about the relationship between transitional justice and peacebuilding. Reference Baker and Obradovic-WochnikBaker and Obradovic-Wochnik (2016: 282), for example, note that ‘[t]he idea that one will lead to the other is often the underlying logic of external intervention, even though it is not always clear how the two practices ought to shape each other’. In her work on the Democratic Republic of Congo, Reference ArnouldArnould (2016: 323) finds that ‘actors attach very different meanings and goals to transitional justice that are deeply embedded in broader peacebuilding goals’, thus underscoring how ‘deeply intertwined’ the two concepts are in practice. Pointing to the importance of strengthening the relationship between the two concepts, Reference MuvingiMuvingi (2016: 20) has emphasised the need ‘to reconfigure TJ [transitional justice] as processes of inclusion that facilitate and support societies affected by violence to address the legacies of the violence and chart pathways for more just and peaceable futures’.

Both in theory and in practice, liberalism – and more specifically the idea of ‘liberal peace’ – has frequently shaped discussions about peacebuilding and peacebuilding agendas (see, e.g., Reference Joshi, Lee and Mac GintyJoshi et al., 2014). Reference de Coningde Coning (2018: 305), however, has pointed to a ‘pragmatic turn in peacebuilding’ at the UN level, marked by a shift away from liberal peace and a new focus on ‘identifying and supporting the political and social capacities that sustain peace’. His ‘adaptive peacebuilding’ (Reference de Coningde Coning, 2018: 305) seeks to operationalise this new emphasis. It also provides a framework for rethinking the relationship between transitional justice and peacebuilding in a way that promotes resilience (see also Chapter 11).

Of critical importance in this regard is adaptive peacebuilding’s systemic approach, informed by complexity theory and its emphasis on the interactions and dynamics between complex and multi-layered systems (see, e.g., Norberg and Cumming, 2008). Reference de Coningde Coning (2018: 305) underlines that ‘[i]nsights from complexity theory about influencing the behaviour of complex systems, and how such systems respond to pressure, should thus be very instructive for peacebuilding’. An approach to peacebuilding that highlights complex systems is similarly instructive for transitional justice, and more specifically for the development of new social-ecological ways of operationalising transitional justice.

Reference McAuliffeMcAuliffe (2017: 250) argues that ‘[t]he vigorously contested process of expanding the interdisciplinary spaces within transitional justice (and hence its ultimate goals) has taken precedence over study of actual post-conflict ecologies’. Foregrounding these ecologies, and the intersecting systems which form part of them, is essential for developing more sustainable ways of doing transitional justice that extend beyond dealing with the past to building more resilient systems and societies. In other words, the relationship between adaptive peacebuilding and transitional justice is symbiotic. The systemic approach that characterises adaptive peacebuilding is highly relevant for developing new social-ecological ways of doing transitional justice. Equally, the need to think ‘innovatively and creatively’ about transitional justice (International Center for Transitional Justice, n.d.) can contribute to actualising adaptive peacebuilding in practice.

In Ahmići, intersecting systems critically limited the on-the-ground impact of the ICTY’s work. A social-ecological reframing of transitional justice requires giving far greater attention to these broader systems, yet it is not about simply ‘correcting’ them through administrative reforms or lustration measures. Most importantly, it is about helping to foster resilient systems that can effectively and positively adapt to adversity. In this regard, Reference de Coningde Coning (2018: 314–315) notes: ‘Adaptive peacebuilding recognises that conflict is a normal and necessary element of change. Its focus is on supporting the ability of communities to cope with and manage this process of change in such a way that they can avoid violent conflict’. Part of operationalising the synergy between adaptive peacebuilding and transitional justice, therefore, is to explore ways of fostering resilience within often-overlooked community-level systems.

In my previous work, I have emphasised the need for transitional justice processes to promote and harness fundamental connectivities between people, including common emotions, feelings and shared values (see, e.g., Reference ClarkClark, 2020a, 2020c). In Cambodia, for example, Phka Sla is an innovative and creative form of transitional justice that tells the stories of victims through the medium of dance. The power of movement, and its cultural resonance within Cambodia’s classical dance tradition, creates emotional connectivity and understanding in a way that words alone may not. Commenting on this, Reference Shapiro-PhimShapiro-Phim (2020: 212) notes that ‘experiences that had in some instances triggered shame and whose suppression had kept people feeling isolated, now generate empathy and a sense of dignity and connection, along with contributions to the historical record’. In other words, a social-ecological reframing of transitional justice is partly about exploring and raising awareness of the core systems that connect people, and thus of strengthening local capacity to advocate for and exert pressure for broader systemic change as part of adaptive peacebuilding.

Conclusion

Žarkov discusses the British television drama Warriors (1999), which focuses on events in Ahmići and on a British battalion based in Central Bosnia. Warriors, she argues, ‘creates two ontological worlds: one for the male, Serb/Croat military Other who is totally dehumanized, and with whom no similarity is allowed; another for the UK soldiers and their families whose very humanity and ethics stand in the way of understanding or relating to the former’ (Reference ŽarkovŽarkov, 2014: 190). War events in Ahmići and their filtering through, and instrumentalisation by, different interconnected systems have contributed to essentially creating two worlds in the sense that Bosniaks and Croats remain deeply divided about those events. The absence of any common narratives, in turn, has contributed to undermining the community’s resilience as a whole.

While the ICTY’s trials had little positive impact in this regard, this chapter has reflected on how a social-ecological remodelling of transitional justice – as part of developing adaptive peacebuilding – might target the systems (including political and education systems, attitudes and value systems) that both hinder and potentially facilitate resilience. Reference de Coning, Richmond and Visokade Coning (2020) emphasises that ‘complex systems cope with challenges posed by changes in their environment by co-evolving together with their environment in a never-ending process of adaptation’. A major challenge is for transitional justice and adaptive peacebuilding to evolve together to promote positive adaptation in systems that are seemingly resilient to change.

Introduction

More than twenty-five years after the 1994 genocide of Tutsi, Rwanda and its people still struggle with its long-term consequences. Applying resilience theory to recovery from genocide poses several conceptual and moral problems. Many resilience approaches emphasise ‘a community’s ability to cope with crisis, adapt to hazards, and bounce back with minimal loss and disturbance’ (Reference BarriosBarrios, 2016: 28; Reference Cutter, Barnes, Berry, Burton, Evans, Tate and WebbCutter et al., 2008). Genocide, however, breaks society in a way that can never be repaired. The dead cannot be brought back to life. Women and girls cannot be unraped. Survivors cannot forget the violence they experienced. Genocide makes ‘bouncing back with minimal loss and disturbance’ impossible. Furthermore, in a society where interdependence, kinship relations, reciprocity and communal forms of life are foundational, mass death destroys far more than lives.

This chapter’s case study of the Rwandan genocide and its aftermath highlights how a contextualised resilience model of recovery raises questions about the notion of resilience itself. Anthropological critiques of resilience often focus on the variability of the term and its vague definitions (see, e.g., Reference BarriosBarrios, 2016; Reference FoxenFoxen, 2010). This volume avoids this trap as all authors proceed from Michael Ungar’s definition in Chapter 1: ‘When referring to biological, psychological, social and institutional aspects of people’s lives, the term “resilience” is best used to describe processes whereby individuals interact with their environments in ways that facilitate positive psychological, physical and social development’. Ungar’s definition incorporates individual and systemic components of change in response to violent conflict, crimes against humanity or other gross human rights violations. Yet, it is still largely grounded in conceptions of resilience emerging from trauma theory, which emphasise ‘the qualities or characteristics that allow a community to survive following a collective trauma’ (Reference Sherrieb, Norris and GaleaSherrieb et al., 2010: 228). While Ungar’s definition embraces complex multi-level systems of interaction, it fails to capture how post-genocide recovery and transitional justice are politicised. Thus, it risks ‘depoliticize[ing] processes that are, at heart, deeply political’ (Reference BarriosBarrios, 2016: 30).

In Rwanda, politics produced the 1994 genocide, so it is no surprise that politics deeply shaped recovery processes. This recovery may have increased resilience by improving ordinary citizens’ mental health, creating social institutions that mitigate conflict in non-violent ways and providing ‘individuals with the internal and external resources necessary to cope with exceptional and uncommon stressors’ (Ungar, Chapter 1). Yet, it also built a strong, centralised state dominated by a single political party and president, both of which were factors that made genocide possible in 1994 (Reference UvinUvin, 1998). This strong centralised state exemplifies how macro-level systemic change seeks ‘to avoid future exposure to stress’ that Ungar identifies as central to resilience (Chapter 1). Yet, this transformation risks reinforcing inequalities that already exist and perpetuating vulnerabilities (Reference BarriosBarrios, 2016: 32; Reference HollingHolling 1973: 14). In Rwanda, poverty created the context where genocide was possible, and it continued after the genocide with long-term physical and psychological consequences. As anthropologist Reference BarriosBarrios (2016: 33) points out, ‘postdisaster contexts are moments when political elites and culturally dominant groups attempt to define disaster recovery in ways that align with their socioeconomic interests and sensibilities’. Systemic factors often privilege recovery for some in society over others. In Rwanda, this reality has led to increasing divides between the wealthy and poor, which may overlap with divides between Tutsi and Hutu, and has solidified the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) political party’s control over the state and economy. Whether this result constitutes resilience is an open question.

This chapter also considers the implications of adaptive peacebuilding and transitional justice for post-genocide recovery. Reference de Coning, Richmond and Visokade Coning (2020: 10) defines adaptive peacebuilding as actively engaging ‘in a structured process to sustain peace and resolve conflicts by employing an iterative process of learning and adaptation’. This definition of adaptive peacebuilding implicitly mobilises key aspects of Galtung’s concept of positive peace. For Reference GaltungGaltung (1969: 183), ‘negative peace’ is the ‘absence of personal violence’, which is an incomplete peace. ‘Positive peace’, on the other hand, is a complete peace where personal violence, structural violence and cultural violence are absent and society is integrated (Reference GaltungGaltung, 1969: 190). In this chapter, I extend de Coning’s definition of adaptive peacebuilding to encompass local, grassroots initiatives that contribute to building positive peace and resilient communities. I primarily consider initiatives led by local non-government organisations (NGOs) and church-based groups as examples of adaptive peacebuilding in Rwanda’s post-genocide period. These efforts exemplify adaptive peacebuilding because they emerged from the genocide and focused on ‘process not end-states’ (Reference de Coningde Coning, 2018: 315–317). Furthermore, they responded directly to ordinary people’s immediate needs without promoting other political agendas. This evidence from Rwanda validates the need for peacebuilding approaches that focus on broader notions of positive peace instead of state-building (Reference AutesserreAutesserre, 2014).

Finally, I examine the disruptive nature of transitional justice for locally ‘adaptive peacebuilding’ initiatives and the state’s use of transitional justice to impose a new, stable (and thus ‘resilient’) social order on Rwandan society. Yet, this resilience fosters inequality and leaves many important issues related to recovery and long-term peace unresolved. Rwanda is an important case study for understanding the relationships between resilience, adaptive peacebuilding and transitional justice because it became ‘emblematic of how peacebuilding and reconciliation emerged as global master narratives of the late twentieth century’ (Reference DoughtyDoughty, 2016: 3). The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) became the model for numerous international transitional justice mechanisms, and Rwanda’s grassroots courts that prosecuted genocide crimes locally have been held up as models for transitional justice predicated on restorative justice and reconciliation.

The 1994 Genocide of Tutsi

During the genocide, approximately 77 per cent of the Rwandan Tutsi population inside the country was killed between 6 April and 14 July 1994 (Reference Des ForgesDes Forges, 1999: 15). The genocide’s triggering event was the assassination of President Habyarimana on the evening of 6 April 1994 when his plane was shot down as it approached to land in Kigali, the capital city. Within hours, special forces units from the Rwandan Armed Forces (RAF) erected roadblocks across Kigali, and Interahamwe militiamen fanned out across the city, hunting down opposition political party leaders and prominent Tutsi politicians. On the morning of 7 April, Interahamwe militias began attacking and killing ordinary Tutsi civilians in Kigali and several other places in the country. By 12 April, genocide had become a nation-wide policy. Between 7 April and 14 July 1994, an estimated 800,000 Rwandans lost their lives in the genocide or ongoing armed conflict between the RAF and the RPF rebel group (United Nations, 1999). The genocide ended when the RPF seized the majority of the country’s territory, sending the government responsible for the genocide, along with the Interahamwe militias and two million civilians, into exile in neighbouring countries.

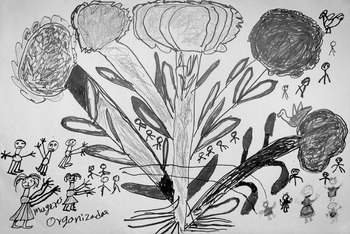

Genocidal violence in Rwanda involved enormous amounts of hand-to-hand killing as the primary weapons used to dispatch victims were farming tools, such as machetes, hatchets, pruning knives and hoes, or traditional weapons such as spears, arrows and clubs. Local government officials organised and recruited ordinary Hutu civilians to find and kill their Tutsi kin, friends and neighbours. Additionally, perpetrators pillaged property, destroyed homes (see Figure 4.1) and slaughtered stolen livestock. Sexual violence and torture featured centrally in the violence. Post-mortem mutilation of bodies and other public displays of gruesome symbolic violence terrorised victims and potential rescuers while fuelling the passions of the most violent killers among the genocidal mobs.

Figure 4.1 Destroyed house.

The genocide took place in the midst of a civil war that began in October 1990 when the RPF, which was founded in Uganda, attacked the country in order to overthrow the government and allow tens of thousands of Rwandan refugees to return home. In 1994, civilians experienced active combat between the RAF and RPF that included heavy artillery in many places, particularly around the capital city. As the RPF took territory, allegations emerged of reprisal killings against Hutu civilians, extrajudicial killings of alleged genocide perpetrators and massacres at public meetings (Reference Des ForgesDes Forges, 1999: 542–545). Although some scholars have alleged a ‘double genocide’, the scale and scope of these killings were incomparable to the genocidal killings that preceded them and have been disproven by at least one study (Reference VerwimpVerwimp, 2003). Nonetheless, civilian killings by the RPF have largely remained unaddressed through transitional justice mechanisms or public memory institutions.

Religious and Spiritual Responses to Mass Violence as Adaptive Peacebuilding

In the wake of the 1994 genocide, the transitional government faced the near insurmountable task of governing a country with no resources and a traumatised population. The withdrawing government intentionally destroyed the country’s physical infrastructure. The genocide and massive exile of civilians more than decimated the country’s human resources. Much of the emergency international aid unleashed by images of Rwandan refugees dying of dysentery in eastern Congo went to support refugee camps on the borders of the country instead of the new government and civilians who remained in Rwanda. In the months after the genocide, the new RPF-led government focused on standard, state-centred peacebuilding (as opposed to adaptive peacebuilding) efforts. It sought to stop direct violence, including continued attacks against genocide survivors, reprisal killings and conflicts over property; to appoint civilian administrative authorities; to provide humanitarian relief and to re-establish the rule of law.

Religious leaders, churches and local communities stepped in between the government response and people’s spiritual and emotional needs. They organised memorial services and burial ceremonies to remember victims and to give people some culturally relevant means to grieve. While intended simply to respond to people’s needs, these activities were forms of adaptive peacebuilding. These religious interventions helped stimulate processes that enabled ‘self-organisation’ and led to strengthening ‘the resilience of social institutions that manage[d] internal and external stressors and shocks’ (de Coning, Chapter 11). Reference BarriosBarrios (2016: 30–31) calls this phenomenon of civil society stepping into the gap between the state and the people ‘resilience as an antipolitics machine’.

While cultural traditions of mourning may be impossible to practise in the wake of genocide, survivors and others needed to process their grief and honour their lost loved ones. Even though many churches became massacre sites during the genocide and some clergy were responsible for genocide crimes, religious institutions were places where Rwandans of all races (Hutu, Tutsi and Twa) came together. During the genocide, the majority of victims had been thrown into pit latrines and inhumed, entombed in mass graves or hastily buried where they lay. Most Rwandans did not know where, when or how their loved ones had died and thus could not perform the necessary religious rituals at their graves. Religious rites such as the consecration of graves remained salient; ‘[i]n the African context, it is unthinkable to honor the dead without religion’ (Reference VidalVidal, 2001: 26; author’s translation). In response, many Roman Catholic Church parishes organised community mourning ceremonies for genocide victims’ families, friends and neighbours. Local genocide survivor groups mobilised to gather victims’ bodies that lay in the open or were discovered in shallow graves and to hold burial ceremonies where priests, pastors or imams consecrated the graves. These community and family-level ceremonies focused on mourning loved ones lost in the violence and honouring religious obligations to the dead (see Figure 4.2). These efforts emerged from local communities and fulfilled local needs (de Coning’s first principle of adaptive building, Chapter 11). They were also participatory processes that required clergy, laypeople, survivors and others to cooperate in the organisation of these activities.

Figure 4.2 Kibuye church genocide memorial.

Ordinary Rwandans and civil society leaders utilised various cultural resources to adapt to the trauma caused by the genocide and civil war. These included religious beliefs and practices, customs of social accompaniment and patience (kwihangana), gift giving and other forms of reciprocity and traditional conflict-resolution mechanisms. Beyond the burials, commemoration masses and prayer services, ordinary Rwandans drew on a broad range of religious resources to promote healing. Some found solace in singing gospel music and praying alone at home. Others returned to the churches where they prayed before the genocide, not a simple proposition in cases where the spaces had become massacre sites or where clergy had participated in the killings. In the genocide’s wake, some survivors renounced churches implicated in the genocide. These survivors gravitated towards charismatic Christian prayer groups, healing worship services or evangelical churches. They found solace in groups that sang gospel music and danced for hours. While these services rarely addressed harm inflicted during the genocide or war, many participants found relief from their ongoing trauma symptoms through their participation in them.

Some Rwandans returned to traditional ancestor or spirit cults, whether alongside or in place of Christianity. Before the genocide, these cults, which the Roman Catholic Church had long maligned and tried to suppress, brought people together across kinship, social group or racial/ethnic lines. In some communities, practitioners of kubandwa or Ryangombe spirit cults resumed their all-night ritual sessions. These seances helped some people address the harms done in the physical realm through the metaphysical intervention of powerful spirits. In this sense, spirituality became a contextually specific resource that enhanced both individual and community resilience.

Several women’s organisations, youth associations, church congregations and church-based organisations engaged in post-genocide activities that can be understood as examples of adaptive peacebuilding. Many of these organisations did not set out with reconciliation or peacebuilding as their goals (Reference BurnetBurnet, 2012: 179–193). Instead, they intended to help victims of sexual violence, to assist genocide widows, to improve the socio-economic conditions of women or to help people worship. These NGOs recognised that, to help rebuild people’s lives after the genocide and war, they must first tackle their material conditions. By addressing the structural violence of poverty, they equipped people to deal with equally vital but more abstract needs, such as psychological health, social isolation or reconciliation. These efforts embody the difference between post-conflict approaches to peacebuilding, which are ‘focused on responding to identifiable risks, and the sustaining peace concept of peacebuilding, which is aimed at investing in the capacity of societies to manage future tensions themselves’ (Reference de Coningde Coning, 2018: 313).

Everyday Practices of Coping as Resilience and Adaptive Peacebuilding

Local-level responses to the Rwandan genocide and its aftermath can be understood as organic forms of resistance and adaptive peacebuilding. In the months and years immediately after the genocide, ordinary Rwandans improvised means to put aside their grief and go on living. Some moved to new communities to avoid daily reminders of their experiences during the genocide. Others remarried or gave birth to new children, not to forget those who perished in the genocide but as a way of creating something to live for. Others buried themselves in the minutiae of everyday life; ‘a life that slowly regained normalcy with the passage of time, they succeeded at least partially in keeping their memories and the negative emotions attached to them – sadness, anger, guilt, and hatred – at bay’ (Reference BurnetBurnet, 2012: 75). Despite their best efforts to forget, embodied memories embedded in everyday life, such as an empty bed, the smell of grilled meat or the sight of a machete, broke through their amnesia and transported them back to the genocide. Psychologists might classify these reactions as forms of negative coping (i.e., repressed memories, avoidance, dissociation). Yet, they were adapted to Rwandan understandings of wellness and how to deal with negative life events. Rwandan cultural norms socialise children to hide their tears from strangers because only family members love and care about them (Reference Mironko and CookMironko and Cook, 1996). To be an adult in Rwanda is to be in control, and public displays of emotion are harshly judged. In the Rwandan worldview, talking about bad events from the past risks inviting the spirits that provoked them to return. Furthermore, these everyday practices of coping align with Ungar’s (Chapter 1) definition of resilience as ‘processes whereby individuals interact with their environments in ways that facilitate positive psychological, physical and social development’.

The genocide had shredded the social fabric. In rural communities, subsistence farmers relied on reciprocity, cooperation and patronage relationships to survive. In the wake of the genocide, these warp threads of daily life were torn. Faced with unimaginable loss and trauma, both physical and psychological, rural Rwandans began to repair the social fabric, often unwittingly, as they muddled through the dire material circumstances in which they found themselves. Women played a central role in these efforts because of their social positions in kin groups and communities (Reference BurnetBurnet, 2012: 168–169). At first, neighbours lived together with little to no interaction, or thinly veiled hostility. Out of necessity, some women tentatively reached out to former friends, neighbours and colleagues. Slowly, over time, communities began to establish some kind of normalcy in their everyday interactions. They exchanged terse greetings. They borrowed household items or farming equipment. In 2001, women in a rural community described to me how astounded they were that Hutu and Tutsi neighbours had sat next to each other at a recent wedding. They explained that this was unimaginable in 1997, just after many Hutu community members had returned from exile in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Despite the progress, many survivors actively opposed these and other conciliatory efforts.

These ad hoc processes of getting by, which emerged in the wake of the genocide, can be understood as forms of resilience and adaptive peacebuilding where people adapt to new circumstances out of necessity rather than through formal state or NGO intervention. These efforts helped build social ties through an iterative process, another principle of adaptive peacebuilding (de Coning, Chapter 11). Precisely because these efforts focused on ‘process not end-states’ and emerged from the devastating change wrought by the genocide, they exemplify adaptive peacebuilding (Reference de Coningde Coning, 2018: 315–317). Furthermore, they demonstrate the need for peacebuilding approaches that focus on broader notions of positive peace rather than state-building.

Social accompaniment was an important cultural resource mobilised in the wake of the genocide that helped reweave the social fabric.Footnote 1 During times of hardship, whether illness or death, Rwandans practise social accompaniment to support those facing difficulties. For example, kin, neighbours and friends will visit a sick person at home or in the hospital. These visits provide moral support to the sick and social support for the family. Visitors never come empty-handed; they bring food, beverages or money. Their gifts help the family through the hardships of lost wages or medical costs. Undergirding all Rwandan social interactions is an elaborate system of gift giving and reciprocity. All important social and life events, such as courtship, engagement, marriage, birth, illness or death, are marked by the exchange of gifts. The immense poverty and period of scarcity that followed the genocide made it very difficult for people to maintain these customs. Nonetheless, they continued them through modest or token gifts.

Rwandans also drew on the cultural concept of patience, forbearance or endurance contained in the verb kwihangana (to bear up under) (Reference BurnetBurnet, 2012; Reference Zraly and NyirazinyoyeZraly and Nyiranyoye, 2010). Rwandans use this term to talk about their own difficulties, and they encourage each other to endure hardship. For example, a common thing to say during a social visit to a sick person is ‘Wihangane!’ This phrase, which is difficult to translate into English, literally means ‘that you might bear it’, or ‘that you might endure’. Perhaps it is best translated into colloquial American English as ‘Hang in there!’ Two additional cultural-linguistic concepts of resilience relevant specifically to genocide survivors were ‘kwongera kubaho’ (to return to life [from death]) and ‘gukomeza ubuzima’ (to continue living) (Reference Zraly and NyirazinyoyeZraly and Nyiranyoye, 2010).

These sociocultural resources for coping with the genocide and its aftermath, as well as the everyday practices of muddling through terrible situations, fit well with a contextualised resilience model of recovery. They also establish the need for peacebuilding interventions to account for local cultural contexts and engage with grassroots actors. Yet, these micro-level modes of resilience can be hindered or completely undone by national or international interventions and the political power of elites.

National Processes of Peacebuilding, Systemic Hindrances and Local Resistance

After ending the genocide, the RPF military forces and transitional government sought to re-establish the rule of law. As citizens’ basic needs began to be met, the government moved onto symbolic, social and legal forms of peacebuilding. Some of these efforts, such as removing race from bureaucracy and public discourse, resonated positively with adaptive peacebuilding efforts at the grassroots level. Other national efforts, especially those related to genocide commemoration and public memory, disrupted adaptive peacebuilding and undermined contextualised resilience in communities by interfering with local recovery efforts.

Among its first symbolic efforts to eradicate racist ideologies, the government eliminated ‘race talk’ from daily life. After the genocide, the government removed racial identification from all government bureaucracy, including the national identity cards that had determined many people’s fates during the genocide, and discouraged use of the terms ‘Hutu’, ‘Tutsi’ and ‘Twa’. In 2001, the government passed a law forbidding discussion of racial differences and the use of racial identification in public discourse (Republic of Rwanda, 2001). At face value, these policies appeared to promote positive adaptation to past violence. Racist ideologies had made genocide possible, and the national identity cards had helped identify potential victims. While these policies sought to heal the nation, they simultaneously helped the RPF political party to consolidate its power.

National unity was a foundational ideology of racial inclusion of the RPF rebel group. The RPF’s ideology of national unity emphasised unifying aspects of Rwandan history and culture (i.e., shared language, culture, religious practices, etc.) and blamed racial division on European colonisers (Reference Burnet, Hinton and O’NeillBurnet, 2009: 84; Reference BurnetBurnet, 2012: 151; Reference PottierPottier, 2002: 109–129). In the aftermath of the genocide, the RPF-led government joined national unity and reconciliation:

[R]econciliation is short for national unity and national reconciliation. … We believe that reconciliation will not come through forgetting the past, but in understanding why the past led to political turmoil and taking measures, however painful and slow, which will make our ‘Never Again’ a reality.

National unity and reconciliation came to encompass a broad range of initiatives reorganising local government administration, formalising and nationalising genocide commemoration and mourning activities, changing the national symbols (i.e., flag, anthem, motto, shield), rewriting the constitution, creating re-education and solidarity camps and setting up grassroots courts to adjudicate genocide crimes. The RPF’s approach to national unity and reconciliation was taught in schools and was ubiquitous in public discourse, ‘from political speeches to NGO conferences to sporting and music events’ (Reference DoughtyDoughty, 2016: 3). National unity and reconciliation thus became the foundation for the new government’s state-building programme and instilled RPF policy at its heart.

The RPF’s approach interfaced not only with national and local systems in Rwanda but also with international systemic approaches to peacebuilding. Many international initiatives related to peacekeeping, peacebuilding, conflict resolution and transitional justice of the twenty-first century were directly modelled after initiatives tried in Rwanda. For example, United Nations (UN) peacekeeping regulations grew to encompass the use of force to protect civilians from gross human rights abuses in response to the UN peacekeeping mission’s failure during the Rwandan genocide. The former UN High Commissioner for Refugees, Sadako Ogata (1990–2000), developed her concept of peaceful coexistence and piloted the project that became ‘Imagine Coexistence’ in Rwanda (Reference OgataOgata, 2000). The UN Security Council created the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and the ICTR as experiments that led to the eventual creation of the International Criminal Court.

Despite these positive national and international contributions to peacebuilding in Rwanda, other national efforts disrupted resilience by supplanting local adaptations to past shocks and stressors resulting from mass violence. In particular, reconciliation efforts often worked against adaptive peacebuilding efforts that had emerged from civil society organisations or at the grassroots. In early 1995, Rwanda’s government displaced family and community-level commemoration efforts with its own national project of commemoration that claimed to promote reconciliation but also reinforced the power of the new state (Reference BurnetBurnet, 2012; Reference VidalVidal, 2001, Reference Vidal2004). In essence, this change constituted a shift from locally led adaptive peacebuilding initiatives to formalised, systemic approaches that utilised some local practices of reconciliation but ultimately served to consolidate the RPF’s political power.

While national reconciliation efforts were clearly needed, they were not always best adapted to local needs. In April 1995, the government organised the first annual genocide commemoration ceremony at the National Amahoro Stadium in Kigali. This first ceremony represented both Tutsi and Hutu as victims of the genocide, unlike subsequent national genocide commemorations. In a ceremony attended by President Pasteur Bizimungu, Vice President Paul Kagame, cabinet members, parliamentarians and international diplomats based in Kigali, the participants re-interred approximately 6,000 anonymous genocide victims alongside several well-known Hutu genocide victims (Reference PottierPottier, 2002: 158; Reference VidalVidal, 2001: 6). A Catholic priest, a Protestant pastor and a Muslim imam consecrated the mass grave beside the national stadium. In this way, Hutu and Tutsi were given joint recognition as victims of the genocide. The decision to recognise both Hutu and Tutsi genocide victims ‘had emerged after debates in the cabinet’ (Reference VidalVidal, 2001: 7; author’s translation).

As the RPF consolidated its hold on political power, public memory of the genocide disseminated through national genocide commemoration ceremonies shifted. This change created systemic hindrances to peacebuilding and privileged the traumatic memories of certain citizens over others. State-led commemoration practices formalised the government’s official history of the genocide and silenced dissent. Only certain social categories were allowed to speak publicly about the past or comment on government policies. Genocide survivor organisations spoke relatively freely in the public sphere, although the government maintained control over their leadership (Reference GreadyGready, 2010).

Later national genocide commemoration ceremonies globalised blame on Hutu and erected a Tutsi monopoly on suffering (Reference VidalVidal, 2001: 7). Survivors of RPF-perpetrated killings were silenced, and the victims’ families could not mourn their lost loved ones in public. In many cases, the victims of RPF killings were often buried in secret mass graves or in graves designated as genocide memorials. These public secrets were known by everyone but remained unspoken, creating an amplified silence surrounding RPF-perpetrated violence experienced by Rwandans of all races (Reference BurnetBurnet, 2012: 111–112). This resounding silence around RPF violence and ongoing human rights violations hindered adaptive peacebuilding efforts in local communities and prevented victims from positively adapting or healing. Even contextualised resilience is inherently political and may not support long-term prospects for positive peace.